Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Ludwik Toresminho

Caricato da

Pablo DumontTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Ludwik Toresminho

Caricato da

Pablo DumontCopyright:

Formati disponibili

ABSTRACT The differential selection and assessment of knowledge is a key feature of

medical practice. This paper presents a study of how doctors select and assess

information in practice. Fourteen internal medicine professors from a relevant

medical school in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, were selected through preliminary interviews

with medical students. The professors were subjected to open-ended interviews. The

resulting material was interpreted through a conceptual framework derived from

Ludwik Fleck, in order to establish the relevant elements of the thought style

characteristic of the way they select and acquire new knowledge. The thought style

that emerged from this set of interviews can be briefly characterized as a largely

intuitive, pragmatic, result-oriented search of relevant (that is, potentially useful in

practice) information. The doctors sought sources with academic credibility, but they

maintained primary interest in practical, experiential knowledge. They also expressed

a rather sceptical stance, at times bordering on cynicism. Despite this mistrust,

doctors lack the resources (time, knowledge of technical aspects of research,

particularly in terms of epidemiology and statistics) to effectively assess knowledge

that is constantly being force-fed to them. This relative lack of resources is worsened,

on one side, by the perception of medicine as subject to frequent and major changes,

and on the other by the vastly disproportionate forces available to those who

effectively produce and distribute such knowledge.

Keywords

epistemology, medical anthropology, medical knowledge, thought style

The Thought Style of Physicians:

Strategies for Keeping Up with Medical

Knowledge

Kenneth Rochel de Camargo, Jr

Cognition is therefore not an individual process of any theoretical particular consciousness. Rather it is the result of a social activity, since the

existing stock of knowledge exceeds the range available to any one

individual. [Ludwik Fleck (1979): 38]

Although it would be far too simplistic to assume that knowledge is the sole

or even the ultimate determinant of actual medical practice, the existing

stock of knowledge (as in Flecks epigraph) surely plays a major role

in this

regard. Much of what a physician does can be described in terms of

making decisions based on trusted knowledge that (s)he is constantly

updating. This means selecting specific items from a plurality of sources,

and also differentially evaluating their relevance and intrinsic merits. It

thus follows that assessing the validity of certain statements concerning

Social Studies of Science 32/56(OctoberDecember 2002) 827855

SSS and SAGE Publications (London, Thousand Oaks CA, New Delhi)

[0306-3127(200210/12)32:56;827855;029788]

Downloaded from sss.sagepub.com at UNIV OF PITTSBURGH on March 25, 2015

828

Social Studies of Science 32/56

medical knowledge is an integral part of medical practice; this is clearly an

epistemological enterprise.

Before proceeding, a cautionary remark has to be made. Giving a

precise definition of what knowledge means depends on the underlying

philosophical framework of choice. The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy,

for instance, ties such definition to a discussion about epistemology [Audi

(1999): 27375], whereas Ian Hacking includes it in his list of elevator

words that is, words that are made to work at a higher level than those

used to describe facts and ideas, and which are usually circularly defined

[Hacking (1999): 2223], and Fleck, finally, simply uses it without bothering to define the meaning. In order to avoid the potential pitfalls of such a

complex discussion, knowledge in this text is equated to the cognitive

content acquired from formal education, professional practice or technoscientific literature.

This paper is a report of a qualitative, exploratory study whose

objective is to answer the following questions: what are the strategies that

doctors deploy in order to keep up with the development of medical knowledge,

particularly in selecting what can be trusted; and how well prepared are they to

do it?

This is a key issue with repercussions in several areas of research and

public policy, such as the quality and costs of medical care; the incorporation of new technologies in current practice; and the emergence and

diffusion of innovation in medicine. Regardless of its importance, however,

this is an aspect that remains relatively under-researched. Most of the work

has been done by epidemiologists, particularly those gathered under the

self-designated label, Evidence-Based Medicine (EBM). Their goals,

however, are clearly normative [see, for instance, Christakis et al. (2000)]

that is to say, their primary interest is to establish how it should be done,

rather than how it happens in practice.

A notable exception to the above rule is the work of cognitive scientists

[see, for example, Allen et al. (1998)], who nevertheless are concerned

with slightly different aspects than the investigation reported here; in

particular, the specifically epistemological aspects of medical reasoning,

which is a key issue for this work, are usually left aside.

Conceptual Framework

Ludwik Flecks comparative epistemology [Fleck (1979)] offers a unique

set of tools to look at the production and circulation of knowledge in

contemporary societies, especially when related to the biological sciences

and medicine. The following lines will present briefly some highlights of his

theoretical developments.1

Two concepts stand at the core of Flecks comparative epistemology:

the thought collective (Denkkollektiv) and thought style (Denkstil). He

described the first as . . .

. . . a community of persons mutually exchanging ideas or maintaining

intellectual interaction, we will find by implication that it also provides the

Downloaded from sss.sagepub.com at UNIV OF PITTSBURGH on March 25, 2015

Rochel de Camargo: Thought Style of Physicians

829

special carrier for the historical development of any field of thought, as

well as for the given stock of knowledge and level of culture. [Fleck

(1979): 39]

and the second as . . .

. . . a definite constraint on thought, and even more; it is the entirety of

intellectual preparedness or readiness for one particular way of seeing and

acting and no other. [Fleck (1979): 64]

It must be stressed that the thought style is not an optional feature that can

be wilfully, consciously chosen, but rather an imposition made by the

process of socialization represented by the inclusion into a thought collective.2 It should also be noted that although style, like Kuhns

paradigm has the kind of semantic fuzziness that allows for all sorts of

abuses, it is nevertheless Flecks word of choice, and I am using it in the

sense of his precise definition.

Fleck distinguishes two major areas within a thought collective in

modern science [Fleck (1979): 11112], one comprising the experts that

actually produce knowledge, which he calls the esoteric circle (he further

details this region, describing the inner circle of the specialized experts and

the outer of general experts), and the other consisting of the educated

amateurs, the exoteric circle. This epistemological topography allows the

distinction between different forms of communication [ibid.: 112]: expert

science is characterized by journal and vademecum (or handbook) science,

the first representing the intense, fragmentary, personal and critical dialogue within a given field of knowledge, and the second a synoptic

organization of the former [ibid.: 118]; the exoteric circle is fed through

popular science, which is . . . artistically attractive, lively, and readable

exposition with last, but not least, the apodictic valuation simply to accept

or reject a certain point of view [ibid.: 112]. Finally, introduction to the

esoteric circle which Fleck compares to a rite of initiation [ibid.: 54] is

based on yet a fourth type of scientific text medium, the textbook [ibid.:

112].

These elements allow for the construction of a geography of an

intellectual field, describing not only peoples and places, but also the

interchanges taking place between them. I do not intend, however, to

ascribe more value to such objects than that of a convenient notation

turning Flecks model into an ontologically founded account would, in a

sense, be going very much against the very gist of his ideas.

All medical institutions (including public health, health care and

medical schools), as well as medical knowledge and practice, are permeated by a specific thought style. This does not mean that medicine is a

homogenous epistemological region. Science itself can hardly be described

in general terms, being divided into different kinds of scientific practice,

which configure different cultures, according to Knorr Cetina (1999). This

is further complicated in medicine since its mainstay is not the production

of knowledge, but its application in a variety of situations according to

Downloaded from sss.sagepub.com at UNIV OF PITTSBURGH on March 25, 2015

830

Social Studies of Science 32/56

ethical principles [Canguilhem (1978): 134]; even though a description of

a medical style of thinking can be sketched [see, for instance, Fleck (1986);

Bates (2000); Luz & de Camargo (1997)], it should not obfuscate the

extreme differences within that field. This might pose an obstacle for

utilizing Flecks framework in effect, any epistemological framework to

analyse the knowledge of practitioners, rather than researchers. It should

be noted, however, that there is nothing in Flecks definitions of a thought

style and a thought collective that specifically ties them to communities of

researchers in fact, he refers to the world of fashion in order to exemplify

the general structure of a thought collective [Fleck (1979): 10708].

Additionally, in a pre-Genesis paper [Fleck (1986)], he describes what he

views as specific features of the medical way of thinking, an expression

that can be seen as a step along the road of the development of the concept

of a thought style. That text dwells quite extensively on the differences

between the medical and the scientific ways of thinking. Taking such

differences into account, as well as the idea that in complex societies there

are multiple intersections and interrelations among thought collectives

[Fleck (1979): 107], one can conceive of at least two distinct thought styles

in biomedicine: researchers and practitioners. There is, however, a wide

area of overlap between them.

Anthony Giddens [(1990): 27] described how lay people rely on what

he calls expert systems in everyday life, meaning the myriad of technologies

that we interact with on a daily basis without really having a firm grasp on

how they work; he goes so far as to describe this trust in terms of faith,

exercised in a pragmatic way. Given the complexity of modern industrial

society, this means that everyone is a lay person in many areas [see also

Knorr Cetina (1999): 67]. Expert systems also exist in medicine, and at

least some of them are as unreachable to regular doctors as to lay persons,

although the former may be exposed to those systems through their

authoritative, textbook science variety, version. This does not mean that

doctors access to journals and all sorts of papers during their careers will

be blocked, but it does mean that they might lack the necessary skills to

effectively interpret what is omitted and compressed in these papers. In a

commentary that parallels Flecks remarks on the same subject, Allan

Young illustrates this point by drawing an analogy between scientific

literature and Conan Doyles stories of Sherlock Holmes:

. . . there is a growing literature dedicated to the rhetoric of scientific

writing. A favourite argument of these authors is that, when scientists

write journal articles, they erase the boundary between real time (contingent, undetermined) and narrative time (logical, causal). The erasure is

achieved through rhetorical conventions, such as the use of passive voice

(results were obtained) and the absence of any reference to human

agency (no personal pronouns). My impression is that, despite these

devices, competent readers of scientific journals can tacitly recognize the

co-existence of the two kinds of time real/contingent and narrative/

determined in the work they read. On the other hand, in popular science

magazines, erasure is attempted through other means: original reports are

aggregated, renarrated and oriented to a shared telos (a notable scientific

Downloaded from sss.sagepub.com at UNIV OF PITTSBURGH on March 25, 2015

Rochel de Camargo: Thought Style of Physicians

831

discovery). Non-scientist readers of these magazines are analogous to

the readers of Watsons accounts, in that they seem inclined to mistake

narrative time for real time. [Young (1995): 357]

Extrapolating from Youngs distinction, my contention is that physicians

are competent readers of scientific journals, only to a limited extent.

Since they lack adequate contextual information, they are unlikely to be

able to unravel the two kinds of narrative in scientific papers, and are more

likely to take statements at face value.

Modern medical knowledge and practice draw from a variety of

theoretical/technical sources, from quantum mechanics (the basis of the

most advanced imaging methods) to molecular biology, filtering them

through several techniques of assessment and validation, which are part of

another discipline, epidemiology, which in turn relies heavily on mathematical more specifically, statistical tools in its trade. None of these

areas of knowledge is the intellectual province of the practising physician;

in Flecks terms, the latter are at most part of the exoteric circle of the

thought styles of those areas. This brings back the question posed at

the beginning of this paper.

The process of schooling that turns the medical student into a fullyfledged medical doctor is an organized inculcation not only of certain

cognitive contents but also of a distinctive way of defining what reality

itself is [Atkinson (1997); Good (1994): 6587]. This learning is integrated

into a system of opinions that, once again according to Fleck, resist

challenges tenaciously, creating what he described as the harmony of

illusions [Fleck (1979): 2738]. An essential part of that thought style is a

set of criteria that identifies trustworthy knowledge, usually identified as

true, objective and scientific, according to what Good dubbed biomedicines folk epistemology [Good (1994): 810]. Indeed, claims to the

firm rooting of biomedicine in scientific knowledge are widespread, as can

be witnessed in the introductory chapters of clinical handbooks [see, for

instance, Barker et al. (1999); Isselbacher et al. (1994); Kassirer &

Kopelman (1991)], or in popular science books expressly dedicated to

dispel any ideas that medicine might not be grounded in science [for

example, Weatherall (1995)]. The abusive use of the word scientific and

the counterpart expression not scientific, however, has been noted at least

by one author [Brewin (2000): 586], who wrote: Why not choose plainer

words like abundant or scanty, convincing or unconvincing, objective or

subjective?

Assessing criteria for the selection of trusted knowledge poses a

problem in terms of Flecks original work. Whereas he used scientific texts

as the basis for his analysis, in order to understand how doctors evaluate

knowledge the starting point cannot be the texts themselves, since the

thought style determines which texts are read, how they are read, and how

(or if) they are incorporated into the available stock of knowledge. A

different approach is thus required. Given Flecks description of a thought

style as a definite constraint on thought, its characteristics should also be

Downloaded from sss.sagepub.com at UNIV OF PITTSBURGH on March 25, 2015

832

Social Studies of Science 32/56

present in other forms of discursive production,3 as speech itself. In this

regard, the meaning of certain words currently used in appraising the

knowledge presented in textual materials, such as science, scientific,

proven, fact, should provide an important insight into this thought style.

In order to understand this meaning, it is necessary, according to Wittgenstein [(1997): 39, paragraph 83], to play the language game where such

meanings make (or gain) sense. In other words, it is necessary to interact

and talk to people who are part of that thought collective. How to talk, and

to which people, are issues that will be dealt with in the description of the

methodology of this study; what remains to be seen in this section is how to

reconstruct such meanings once the pertinent data is gathered.

Methods

In order to gain access to the language games of my subjects, I decided to

use interviews as my main methodological instrument [for an in-depth

review of the methodological and theoretical issues related to interviewing

techniques, see Fontana & Frey (2000)]. It should be noted that the use

of interviews in this context is not based on the realist assumption that

. . . interview responses index some external reality [Silverman (2000):

823], but rather on a narrative approach, where . . . we open up for

analysis the culturally rich methods through which interviewers and interviewees, in concert, generate plausible accounts of the world [ibid.: 823].

Even then, it could be argued that perhaps a classic ethnographic study

would be a better approach.

I have three reasons for my methodological choice. First of all, I would

say that I sacrificed depth for breadth; given the available time for fieldwork, I would be able to study at most one ward in the hospital, and thus I

would have had access to one, at most two, of my interviewees in the

process, whereas I considered a multiplicity of interviewees to be important for the study the advantages of having multiple voices in a

comparable study were stressed by Gilbert & Mulkay [(1984): 188].

Second, it must be noted that, having graduated in medicine, I am part of

the same esoteric circle, and thus at least minimally competent in that

language. Although firsthand experience cannot be equated to a rigorous

ethnographic procedure, it certainly allows for an intimate knowledge of

the field. My previous personal and professional experience served both as

context for filling gaps and, at least to some extent, a measure of comparison. Finally, as the results will show, much of the actual process of

selecting and incorporating new knowledge takes place in spaces other

than the workplace, and a traditional single-site ethnographic observation

would leave these out.4

I interviewed medical school professors, because they are in charge of

the reproduction of values in the profession. Additionally, those professors

are also usually respected doctors too, thus occupying a pre-eminent

position in the medical field. This meant that, in terms of language games,

Downloaded from sss.sagepub.com at UNIV OF PITTSBURGH on March 25, 2015

Rochel de Camargo: Thought Style of Physicians

833

at least three different kinds of interaction could be postulated beforehand

in the context of this study: among clinicians; between these and medical

students; and finally between the clinicians and the interviewer myself.

Based on my experience, I consider the first two of these interactions as so

intertwined in the clinical setting as to be part of an inextricable continuum, and the third a mere variation within this continuum. In effect,

with at least four of the subjects, this is a de facto situation and not an

assumption; the interviews were indeed pieces of an ongoing conversation,

for almost 20 years, about those same issues.

I chose one of the most traditional and respected medical schools in

Rio de Janeiro for the field research,5 which is also the medical school

where I graduated. This choice was based on the assumption that such

familiarity would make the initial steps in the field easier, an assumption

that proved to be correct with the unfolding of the research, although it

brought about other difficulties, which will be dealt with later in this

paper.

The next step was to choose which professors should be interviewed.

First of all, I decided to choose internal medicine professors as interview

subjects, rather than more specialized professors, since all students are

exposed to internal medicine for long periods of time during their training

in medical school. Medical specialists tend to teach short-term courses,

thus having less exposure to the students and being less influential, on

average, in the process of building the future doctors worldview.

In order to narrow the set of interviews further, the most respected

professors were identified. An assistant researcher, a medical student who

joined my research project, conducted a series of interviews with medical

students in the last three years of medical school (these students had

contact with most, if not all, the internal medicine professors). My

assistant asked the students to identify the best professors, in their opinion.

These interviews yielded a list of 18 names, among which were some

University hospital staff members who, although not professors in the

strict sense of the word that is, not part of the medical school faculty

were considered as such by the students. It was not possible to interview 4

of the 18 professors during the time frame of the study, for different

reasons (vacancies, study leaves, and so forth). This left 14 interviews,

which provided the basis of this paper.6

The subjects were contacted in their workplaces at the University

hospital, when the schedule for the interviews was arranged. Formal

introductions were unnecessary at this hospital, since I had previous

acquaintance with all the subjects. All interviews took place in a relatively

quiet room near the wards in which the subjects usually worked, during

free slots of their usually busy schedules. All interviews were taped, with

consent from the interviewee, and ranged in time from 35 minutes to an

hour and 40 minutes (approximately). Both the initial contact and the

opening of the interviews were standardized: I informed the subjects that I

was conducting a study on medical teaching, and during the interviews

Downloaded from sss.sagepub.com at UNIV OF PITTSBURGH on March 25, 2015

834

Social Studies of Science 32/56

I asked three standard questions: what was the doctors academic background; what, in her/his view, were the most important features in a

doctor; and what would an ideal medical school be like. These questions

had no relevance in themselves, as they were designed to help set up a

shared orientation to the questions that followed. As the interviews proceeded, I would ask, for example, how they updated their knowledge, and

how they sifted relevant information from the overwhelming jumble that

medical journals and, more recently, the internet, presented. If research

activities were not spontaneously mentioned, I would ask about their

personal involvement with research, and/or the relevance that it would have

in medical education.

Interviews always present the risk of inducing subjects to respond with

what they would deem appropriate answers, even if these did not actually

represent their views. I chose this extremely indirect approach in order to

minimize that risk.7

The resulting interviews were transcribed, and the text files were

stored using a free software package called Logos, a textual database system

developed in Brazil specifically as an aid to the analysis of unstructured

data [de Camargo (2000)]. Each interview generated a record in the file,

which was analysed for the presence of recurring themes connected to

medical knowledge, practice and their relationship. Text chunks were

coded according to the presence of these themes, and then regrouped

according to them. The choice to work with themes rather than specific

words is due to the fact that several different words can be semantically

related, even if they are not exact synonyms, and because the goal of the

research is to reconstruct a thought style, not a lexicon. The themes and

the textual groups thus produced are presented in the following section;

original passages have been translated from Portuguese to English by me.

As far as possible, I tried to preserve the fluidity and lack of formality of a

spoken interaction while translating from Portuguese to English. What may

look at times like broken English is the result of a deliberate effort to

preserve the spontaneity and even the awkwardness of the spoken language, instead of trying to correct and thus sterilize it.8

Results

Characteristics of the Respondents

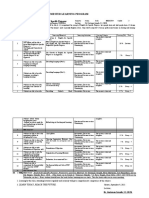

The interviewed subjects are listed in Table 1. Names have been replaced

with pseudonyms in order to preserve interviewees privacy.

A few characteristics of the group should be noted. First, there are

many fewer women than men in the group, probably reflecting the composition of the faculty of the medical school. It is also of interest that the

distribution of time since graduation is heterogeneous, with aggregation in

some periods; this reflects changing recruitment policies in the University

over the years. The majority of the interviewees graduated from the same

school, which is not an unusual situation in Brazil. None of them has a

Downloaded from sss.sagepub.com at UNIV OF PITTSBURGH on March 25, 2015

Rochel de Camargo: Thought Style of Physicians

835

doctoral degree other than the MD (although one of them has a qualification which is considered equivalent in Brazil to a PhD), and four of them

had not even a masters degree. This is also not unusual in medical schools

in Brazil, especially in the clinical courses, although this situation has been

changing in recent years; it should be noted that this group is better

qualified in this sense, anyway, than the bulk of the professors of the same

department (or comparable hospital doctors), and this may have had an

impact on their teaching skills and thus their appreciation by the students.

Conversely, it might be argued that these are more committed professors,

who would be more likely to invest in an academic career, and would also be

more likely to receive better evaluations from their students. In any event, it

is an outstanding group among their peers also from this point of view.

Recurring Themes in the Interviews

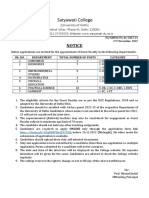

The process of coding the transcriptions of the interview process in itself

an integral part of the analysis [Ryan & Bernard (2000)] yielded six

recurring themes in the interviews. For reasons of space, only one of the

themes the second most frequent in the interviews, and undoubtedly the

most relevant for the core issue of this paper will be extensively presented

and analysed here; the other five will only be briefly commented upon. The

themes are presented in Table 2.

TABLE 1

Characteristics of the Respondents

Pseudonym

Sex

Year grad

Inst stat

Other degree

School egress

Alberto

Alexandre

Carla

Celia

Celso

Jorge

Lauro

Luis

Luiza

Marcos

Milton

Renato

Roberto

Pedro

M

M

F

F

M

M

M

M

F

M

M

M

M

M

1965

1974

1992

1984

1968

1983

1959

1984

1968

1976

1986

1976

1986

1975

professor

physician

professor

physician

professor

prof/phys

professor

physician

professor

physician

prof/phys

professor

professor

physician

livre docncia

master

residency

mastera

master

mastera

none

residency

master

residency

master

master

master

residency

no

yes

yes

no

yes

no

yes

yes

yes

yes

yes

no

yes

yes

Notes: Year grad is the year of graduation in medical school; Inst stat is the current institutional

affiliation (whether a faculty professor or a university hospital physician note that two of

them have a double affiliation); Other degree is the highest academic degree held besides that

of MD, a means incomplete, and livre docncia is a title originated from the old privatdozent

in Germany, usually accepted in Brazil as equivalent to a PhD degree, it is attained through

the presentation and public exam of an original thesis and a written exam, without any formal

credits in recent years it has been increasingly phased out in most Brazilian Universities;

School egress refers to whether the interviewed subject graduated in that same medical school

or not.

Downloaded from sss.sagepub.com at UNIV OF PITTSBURGH on March 25, 2015

836

Social Studies of Science 32/56

Table 2

Themes, Definitions and Summaries

Theme

Short description

Summary from interviews

I

Undergraduate

teaching

ideal models;

assessment of current

situation; assessment of

interviewees rle

There is a diffuse dissatisfaction among the

interviewees about some aspect or other of

teaching in medical school, especially in terms

of a curriculum which is considered

inadequate. This seems to be a widespread

attitude in medical schools, judging by the

expressive production of critical evaluations of

medical curricula [see, for instance, De Angelis

(1999); Jason & Westberg (1982); Gastel &

Rogers (1989)].

II

Research

rle of research in

medical education;

interviewees

participation in

research; firsthand

knowledge of ongoing

research in the

institution.

Personal participation in research activities is

scarce and sparse, mostly related to preparing

some thesis for a postgraduate course, and

confined to that experience. The subjects didnt

make any references to regular engagement in

the production of papers for publication, and

in fact there are no records of expressive

production in that area for most of the

academic staff of the Clinical department of

the medical school in the Universitys data

systems. The interviewees also had practically

no knowledge of any ongoing research at the

University hospital.

III

Post

graduation

whether medical

educators need other

postgraduate

qualifications.

Even for those who did have a graduate degree

other than the MD such credentials werent

considered important for medical educators.

For all the interviewees, it seems that there is

but one necessary and sufficient requisite for

being a good professor in medicine: being a

good doctor.

IV

Professors &

physicians

differences between

both rles in terms of

responsibilities, tasks

and attributed status.

Although in theory one could draw a precise

separation between medical assistance and

teaching, in practice these limits are completely

blurred. Clerical training depends

fundamentally on a hands-on approach, and

particularly in the university hospital it is

impossible to ascribe clear boundaries to

separate medical care and education.

Nevertheless, some of those among the

interviewees who have the institutional status of

physicians have a strong perception of their

position as inferior to teachers.

V

Professional

values

interviewees views on

such values.

All the interviewees highlighted the relevance of

humanitarian values such as compassion,

dedication, and so on and so forth. Not much

elaboration was done on this topic, it was

brought about basically in response to the

question on the characteristics of a good

doctor.

Downloaded from sss.sagepub.com at UNIV OF PITTSBURGH on March 25, 2015

Rochel de Camargo: Thought Style of Physicians

837

Table 2

continued

Theme

Short description

Summary from interviews

VI

Knowledge

strategies and sources

for acquisition; critical

assessment; relationship

with practice.

This theme will be presented in detail in the

following pages, with quotes from the interview

transcripts and a few comments on them.

Detailed Presentation of Text Excerpts Related to the Theme of Knowledge

I grouped the text excerpts in three subsections; they reflect recurrent subthemes or trends in the interviews that usually coalesced after the interaction had developed for a while. Once again, for reasons of space, I had to

limit actual quotations to a bare minimum.

First Sub-theme: A Doctors Job is Never Done Knowledge is Never

Complete

This theme is commonplace in medical lore: there is a need to keep up-todate about what is on the cutting edge of medical knowledge, which is

assumed to be something that is growing all the time. At the same time, the

other demands of the medical profession leave little room for this activity.

This is immediately evident on the following quotes from the interviews:

I think that, for a clinician, keeping updated in medicine is very difficult. . . . Its impossible, especially now, with computers, the internet, with

. . . an increasing diffusion of computers . . . to keep updated. . . . its very

difficult, with all your activities, and outside the profession, your family,

your other activities, even your leisure, for you to arrange time for

reading, then you do what you can, but its very difficult. [Luis]

I mean, Im there on a daily basis from eight to five, and there are two

days that I go on straight until 8pm, at the outpatient unit. I have a weekly

shift here 24 hours. When will I study? When will I take a course? I cant,

I have to do it myself, isnt it so? On my own. [Marcos]

The other day . . . about a month ago I read a report . . . a quote in a

journal . . . that on the average two million new papers are published

worldwide . . . that means journals all over the world . . . thats per year,

two million papers. In terms of major cardiology studies, there are three

hundred great studies every year . . . theres no human being, in principle,

that has enough memory for all that stuff . . . per year . . . and has enough

time to read it all. [Milton]

The same ideas are present in the next excerpts. First it is Alberto, one

of the elder members of the group, who expresses in these words the large

amount of reading that he is doing himself, and which, presumably, should

be an indication of how much needs to be done on a regular basis:

I dont read medical journals, only. One day I read a journal, the other I

read a book. If you got . . . Im reading the Stein [book], which is a huge

Downloaded from sss.sagepub.com at UNIV OF PITTSBURGH on March 25, 2015

838

Social Studies of Science 32/56

book, this thick . . . Im reading it and Im going to read it from cover to

cover . . . Then, I, being a clinician, am going to read this book from cover

to cover, the same way Ive read many others, from cover to cover.

The need for constant updating is expressed even more strongly in this

excerpt:

. . . you force the student and there is no other word, its really force

to realize that he must be studying all the time, otherwise youll be . . .

youll become outdated . . . the drugs . . . its really crazy . . . the number of

drugs that they introduce to the market! [Celia]

Second Sub-theme: Looking for Needles in Multiple Haystacks

Selection Strategies

During the interviews, I asked the doctors how they select or triage

relevant/trustworthy/correct information from the multiplicity of sources

that constantly bombards them. The actual wording of the question varied

according to the unravelling of the interview. This usually produced the

most awkward situations: interviewees hesitated, grasped for words, ran in

circles, and at times hardly made any sense at all. I often had to rephrase

and reinstate the question several times before getting something from it,

and even then, in some cases replies were not exactly informative. Usually

I gave up pursuing the matter any further, for fear of inducing responses

out of excessive pressure. The most relevant aspect from the following

excerpts is that there is no single pattern to them. I chose the term

strategies rather than criteria because, in all cases, no explicit criteria

were apparent, and they presented their behaviour in terms of examples,

rather than as a methodical exposition of a set of rules. Actual strategies

varied from subject to subject, and were usually fuzzy and difficult to

explain. Personal preferences, convenience, bits and pieces of information

such as those derived from developments in epidemiology seemed all to

play variable parts in the composite strategies employed by the

interviewees.

Luis pointed to a mixture of personal interest, relevance for actual

practice, the relative authority of authors and journals, and a vague check

of methods:

. . . first you may try . . . an idea, you see? . . . see where this paper, this

work came from . . . [it also should be considered] . . . the method they

used, the . . . the importance that it has . . . then at times, you have themes

without . . . with very little interest to me. Such themes, or such subjects,

I wont . . . I wont pore over. Now, if its something that might have some

interest to me, or might have . . . might help me, youll make at least a

superficial reading of that, to check what its about, and then if its

interesting youll read the whole paper . . . [Luis]

Alberto mentions the practical interest and the cheats he uses as

shortcuts:

I get a journal . . . [unintelligible] I look at the papers abstract. I look at

the abstract . . . if the guy . . . is talking about something specifically, if its

Downloaded from sss.sagepub.com at UNIV OF PITTSBURGH on March 25, 2015

Rochel de Camargo: Thought Style of Physicians

839

clinical stuff, I read everything. Now, what will I read? I wont read . . . an

absurd, material and methods, as a general rule. I see it this way . . .

[Alberto]

In another excerpt, Alberto makes his position as a mere consumer of

knowledge totally explicit, even if intertwined with medical practice after

stating that research is important for generating new knowledge, he says

that he does not have resources for doing it, concluding this way:

And I get the conclusions of research done outside. If I had to have this

. . . I wont try to conclude anything, Ill get the conclusions that are

already available . . . [Alberto]

Jorge produced, after great insistence, a vague description of standards,

without really elaborating them. He also refers to positions of authority,

and his use of the verb believe is particularly noteworthy:

Scientific knowledge is that which is validated, in my understanding by

criteria . . . accepted by the scientific community. Then . . . depending on

the criterion, also the basis of the work . . . I believe in allopathic

medicine, I had my schooling in this direction . . . I have to start with a

randomized work, with criteria, controlled, published in a journal . . .

[hesitates] with an editorial, a decent reviewing committee . . . I think that

this is how it goes . . . a scientific work is one that follows norms

universally accepted by science . . . [Jorge]

Celia also emphasizes personal experience and makes interesting remarks

about the role

that reporting failures has in establishing credibility:

I also check . . . how many of these patients were unsuccessful. This is even

a way for you to lend credit to that research, at least I think so. Because if

you start out stating that your research was wonderful, was formidable,

theres something wrong with it. Could we be so bad at researching, that

we have so many mistakes, so many . . . losses, you see? Then I try to

check this. Theres always a lot of unsuccessful situations, and I think that

this gives it more credibility this is a bit weird . . . But I think it has more

credibility. [Celia]

Carla, the youngest interviewee, emphasizes the role

of personal preferences, but also of dislikes; she also mentions needs arising from practice:

I . . . first of all, theres a lot of personal interest into it . . . thats the first

thing . . . themes I like . . . Its the two extremes, stuff I like a lot and stuff

I totally dislike, but is the stuff that I force myself to study. Stuff that I like

a lot, like . . . textbook, and read a paper, journal . . . the New England . . .

and stuff I dont like, then, I get the textbook, read, read, read until I can

make sense of it . . . review papers, that also help to understand . . . and so

on. And the rest I fetch out of curiosity. Things that are fashionable also. I

dont have a very large private practice, but . . . things that turn out at the

office that we are forced to study, things that the patient . . . the patient

himself brings to us . . . [Carla]

Milton also talks about institutionally established sources of authority:

Downloaded from sss.sagepub.com at UNIV OF PITTSBURGH on March 25, 2015

840

Social Studies of Science 32/56

. . . [hesitating] We select . . . by the authors, the sources . . . whos

publishing it . . . the New England is the journal of the Harvard Medical

School. . . . [Milton]

Of all the interviewees, Roberto seemed the most disoriented by this

line of questioning, and referred vaguely to the role

of common sense as a

yardstick, but at the same time assuming it as an attribute or property of

individuals, rather than a learned skill:

. . . [hesitates] . . . I see that issue from the point of view of common sense

in medicine, and thats whats more important. That depends a lot on the

person whos practising, I dont know if that can be taught . . . [Roberto]

But Pedro is straightforward: it is important to have scientific that is,

proven knowledge. He made no further elaboration on this point.

Scientifically proven is research stuff, isnt it? Theres a lot of options. You

see, to prove aspirin as anti-adhesive for platelets . . . it was proven. There

were several other drugs which were not proven. Theres another slated for

release next year. Itll be released . . . thats what Im saying, anything can

come out of this . . . things change . . . [Pedro]

Luiza also stressed the importance of the journal that publishes the paper

as a source of credibility, but introduced a cautionary note:

Youll go after a paper, for instance, a paper from the Archives [of Internal

Medicine], you already have a certain basis of those who already did that

kind of treatment, based on . . . and thats why a clinician who is in the

wards, seeing patients . . . working with the population, has to be updated,

in fact. He is reading not to adopt the last paper, of the last person, but

that factor used worldwide . . . that routine, which conduct to be taken,

thats important. You dont have to know the last thing . . . but the last but

one, whats being done all over the world . . . [Luiza]

Alexandre was the only interviewee to mention the existence of forces that

have to be resisted when it comes to acquiring updated medical knowledge,

although even he did not manage to be particularly precise when it came to

proposing alternatives:

The pressure, the media, and so on . . . if this is something important or

not . . . if someone says this is the best available antibiotic . . . you have to

prescribe this antibiotic, it cures everything, heres the bacteriology . . . I

think that the individual needs something like . . . the need for this critical

appreciation, you do not accept immediately . . . an evidence, even what is

your knowledge . . . some journals that try to filter some things, which are

not exempt from pressure . . . I think that clinical epidemiology is a

weapon that you need to provide data for the patient, for the doctor so

that he can make certain decisions. [Alexandre]

Third Sub-theme: It Aint Necessarily So Scepticism and Mistrust

In the previous subsection, a common trend of delegation can be seen in

the excerpts instead of criteria of validity, there is an implicit accreditation placed on certain sources, mostly institutional, particularly certain

Downloaded from sss.sagepub.com at UNIV OF PITTSBURGH on March 25, 2015

Rochel de Camargo: Thought Style of Physicians

841

journals; the New England Journal of Medicine shines brightly as a consensual symbol of cognitive authority. From these it would seem that the

interviewees are content to play a passive role

when acquiring knowledge.

Not so. The following set of excerpts shows several reasons for not taking

such information at face value, and reinstating once again the role

of

personal experience in the process.

Roberto mentions the risk of relying on knowledge that is inherently

unstable:

. . . we cannot base our conduct on a paper that just came out, because

next week there might be another proving just the opposite, then we have

to be extremely cautious. There are some consensus panels that some

[medical specialties] societies do . . . consensus on the treatment of

hypertension, consensus for lipid disorders . . . which is the most discussed on this issue in cardiology . . . and even these consensus results

cannot be applied, because its one thing trying to standardize conduct,

especially in bulk . . . [pauses] . . . [Roberto]

Pedro refers to the same phenomenon, with even more emphasis:

. . . what happens is this: thats what Im talking about, theres no use in

reading too much, todays truth is tomorrows lie . . . Isordil for heart

failure . . . when it was introduced, it was like that: every hour and a half

you had to administer a sublingual capsule . . . Now you see that . . . with

use of the medication [unintelligible] . . . How many drugs you see that

are introduced, in the beginning as miracle drugs and then . . . disappear

. . . a few years afterwards. You see that a lot, its not just a few cases, its a

lot. Whats the use of a book that comes out every two years . . . theres

a lot that was lost and was not for too long because it was not scientifically

proven that it is effective . . . [Pedro]

Alberto makes a penetrating critique of the effects of publish or perish

policies in the overall quality of what is published:

. . . the guy does some work on gases. Darn! And in the end, what does the

guy do? OK, gases. Alright, lets study gases. But do you know why

the guy studies gases? To show off. He has to do some work. So, they say,

like: a good doctor is a doctor that publishes. Then anything gets

published . . . any rubbish gets published. [Alberto]

And in this next excerpt, Alberto illustrates how medical perception can be

biased by theoretical conditioning, establishing very different roles

and

expectations for the researcher and the clinician:

If [a doctor] only reads myocardiopathy, thats all hes going to see.

Everything that turns out in front of him from that moment hes trying to

learn about it on is myocardiopathy . . . Then I think that a doctor has

to read everything. . . . Unless hes a researcher. When hes a researcher on

disease and pericardial diseases, then hell only read pericardium . . .

[Alberto]

These excerpts demonstrate that even when physicians recognize the

epistemic authority of scientific sources namely, research and published

Downloaded from sss.sagepub.com at UNIV OF PITTSBURGH on March 25, 2015

842

Social Studies of Science 32/56

papers they recognize inherent characteristics that preclude an immediate transposition of what is published to actual medical practice,

either because recent knowledge is also unstable knowledge, or because

relevance criteria differ between the scientific arena and their daily practice. A second thread of argument, not exactly like the preceding one, but

closely intertwined with it, is concerned with the rle played by the

pharmaceutical industry and its marketing strategies.

Celia strikes a similar note, raising additional reasons for taking results

from papers with a grain of salt. She is speaking ironically about new drugs

that are released to the market:

Theyre all wonderful, arent they?. . . Oh, its so good . . . perfect, marvellous, and all that . . . Then youll want your own experience, to know

whether for your population, if that drug was good . . . how to achieve

this? Of course theres the literature, theres someone who researched

3000 patients using that drug . . . but sometimes its your patient who is

the one where it wont work, but its a starting point . . . You wont always

think that . . . that its just advertising of the drug companies, and so on,

but sometimes it does not work, Brazilian patients, you see . . . these

researches are . . . USA, Europe, the biotype is different . . . the socioeconomic status is different too . . . But I think that this is the way we do it

here . . . [Celia]

Marcos spells out the biases introduced by the pharmaceutical industry

and the need of personally checking claims of effectiveness:

We get a patient in the ward, and we use that drug that has been

introduced to the market for two, three months and we begin to apply it in

the ward. Then you see in loco the created situation, youll see if thats just

a fiction created by the pharmaceutical companies or if its really

effective.

Celia, once again, is even more explicit in describing the role

of the

pharmaceutical industry in shaping medical knowledge, in this passage:

You attend to a lecture where he says that the best drug to use against high

cholesterol levels is X . . . then you look into it, he didnt compare it with

anything, you know, and in fact . . . Why did he say it was X? Because he

was funded by a drug company. That is . . . this is due to . . . this has to be

written in the research reports, that you did it for the X, Y or Z drug

company. The . . . I think it gets a bit biased when the drug companies are

behind it, but unfortunately in the majority . . . [Celia]

And the same point is made by Luiza:

And the pressure from the pharmaceutical industry is really something . . .

They go to the hospital, to the ambulatory, drugs for hypertension . . . the

patient is there . . . you wont administer a last generation inhibitor . . .

betablocker, nothing like that, because thats not our option . . . you know

this . . . youll see a lot of patients, youre consulting everyday . . . youre

receiving the guy from the drug company marketing placing lots of free

samples there. [Luiza]

Downloaded from sss.sagepub.com at UNIV OF PITTSBURGH on March 25, 2015

Rochel de Camargo: Thought Style of Physicians

843

Discussion of the Findings

Considering the themes that were only briefly reported here (see Table 2),

at least two of the statements made at the beginning of this paper are

reinforced:

1. These doctors are not scientists, they are not involved in producing

knowledge according to the institutional practices of science, and are

consumers of knowledge produced elsewhere. It might be argued that

this derives from the fact that Brazil is a country with far less resources

than the most developed ones, but preliminary results from interviews

conducted with Canadian doctors indicate otherwise;

2. The lack of differentiation between the roles

of physicians and professors in that institutional setting (the University Hospital), as well as

the lesser importance attributed to other academic degrees, is important evidence of the placement of medical education as part of the

broader medical field.

A major issue is that of the perceived informational overload what I

would call the Sisyphus Effect. Doctors lack of spare time, at least in this

group, is an indisputable fact,9 as is the sheer volume of new publications

poured continuously through an ever increasing number of journals. But

what might seem a next logical step, the commonsensical notion that

medical knowledge is increasing at a dazzling pace, making everything

change almost overnight, must be carefully considered.

This was evident in the quoted interview excerpts, but more examples

can be found almost everywhere without much effort. The clinical textbook quoted from earlier, Harrissons Principles of Internal Medicine [Isselbacher et al. (1994)], has in its opening pages a disclaimer, encouraging

readers to confirm the information it presents with other sources. That

note begins with the following sentence: Medicine is an ever-changing

science. Even more explicitly, an Evidence-Based Medicine (EBM)

manual justifies the need for EBM with the following reasoning:

First, new types of evidence are now being generated which, when we

know and understand them, create frequent, major changes in the way

that we care for our patients. Second, it is increasingly clear that, although

we need (and our patients would benefit from) this new evidence daily, we

usually fail to get it. Third, and as a result of the foregoing, both our upto-date knowledge and our clinical performance deteriorate with time.

Fourth, trying to overcome this clinical entropy through traditional continuing medical education programs doesnt improve our clinical performance. . . . [Sackett et al. (1997): 5]

The idea of progress of science and medical advances could be

challenged on several grounds, but even if we take these for granted, how

frequent and major are the changes that they bring about? A study of

innovation in medicine is far beyond the scope of this paper [an example

of such studies, an extensive analysis of innovation in imaging techniques,

can be found in Blume (1992)], but at least a few remarks are in order.

Downloaded from sss.sagepub.com at UNIV OF PITTSBURGH on March 25, 2015

844

Social Studies of Science 32/56

The bulk of innovation, both in terms of medical equipment and

drugs, comes currently from the private sector.10 This means that economic forces play a major role

in such dynamics, and should be taken into

consideration when analysing such changes in medicine. These markets

have a limited number of players, high-tech companies that are part of

large transnational corporations. In such situations, competition usually is

not price-based. Considering the sheer volume of resources these corporations have, a price war could rage for too long, and cause too many

economic casualties, possibly turning even the eventual winners final

triumph into a Pyrrhic victory. In such situations, companies compete

through a strategy known as product differentiation. In order to boost sales,

and instead of offering lower prices, companies rely on, often minute,

technical differences in their products. This means, not only emphasizing

minor differences between products from different companies, but also

promoting successive versions in a line of products from the same company. The temporal evolution of product lines in the auto industry and in

some branches of consumer electronics, such as audiovisual equipment,

provides concrete examples of such strategies. Going back to medical

industries, there is a further element to be considered: patents. Copyrights

and protective legislation are effective shelters for securing revenues in

certain market niches.

Analysing innovations in medicine from this angle, frequent, major

changes seem less likely. Products have a life cycle, and introducing new

products in the same categories in which old ones have not yet fully

realized their profit potential becomes an unlikely scenario. A steady flux of

innovations, which are either frequent or major, but rarely, if ever, both at

once, makes more economic sense. Reinforcing the idea that innovations

occur at such a breathtaking pace, however, can be an extraordinarily

effective marketing strategy. This is a point that will be fully addressed later

in this section, but, for now, what needs to be stressed is that this brief

incursion into microeconomics gives at least some reason for taking claims

about continuous revolutions in medical technology with a grain of salt.

With regard to notions of progress, we should also note the absolute

dominance of English-speaking publications (both journals and textbooks)

as the references for the interviewed doctors. This dominance is so overwhelming that many of the interviewees used an expression to refer to

textbooks livro-texto which is a literal but meaningless translation into

Portuguese of the English words book and text.

The next element to be analysed is the selective strategy, or strategies,

employed by the interviewed doctors. First of all, there is an interesting

aspect in the way that they surfaced in the interviews. Considering that we

were discussing a routine operation in their daily lives, the fact that the

interviewees were at a loss to explain it is particularly intriguing. There is

an interesting analogy here with the description of diagnostic strategies

presented by Sackett et al. (1991), especially with pattern recognition.

According to these authors, a key component in medical diagnosis is the

immediate recognition of characteristic clusters of signs, which are grasped

Downloaded from sss.sagepub.com at UNIV OF PITTSBURGH on March 25, 2015

Rochel de Camargo: Thought Style of Physicians

845

as a whole, and not analytically one by one. The interesting thing to note is

that they say that, although an ex post facto reconstruction of a stepwise

procedure may be described by the doctors, it does not describe what

actually happens in practice. The actual mechanism of pattern recognition

takes place far too quickly for any deliberative procedure. This is in line

with Ginzburgs conjectural paradigm [Ginzburg (1980)], which could also

be described as a form of pattern recognition. It could thus be hypothesized that doctors employ similar strategies to sort out information when

seeking to update sources they use when diagnosing, quickly selecting

certain elements and reconstructing them in a gestalt. The difficulty they

experience in explaining such procedures would may arise from the fact

that they are not following a flowchart when executing their strategies, but

operating on a much more intuitive level.11 This observation also lends

weight to the hypothesis that ordinarily doctors are not fully competent to

evaluate scientific journals. If this were the case, more definite, fully

conscious and systematic procedures could be expected.

The issue of competence demands some clarification. We can distinguish at least two separate epistemic cultures, to refer once again to

Knorr Cetinas expression, within the field of biomedical research: laboratory experiments and epidemiological validation. The first is characteristically related to hard sciences such as molecular biology, and provides

general frameworks for explaining why certain drugs work the way they do,

or how pathogenic agents produce the features of specific diseases. These

explanatory models are, to a large extent, irrelevant to actual medical

practice, since a doctor does not need to know anything about quantum

mechanics, for example, to interpret the result of a MRI scan. Epidemiological validation, however, has a decisive influence in defining standards

for medical practice. Marc Berg, for instance, shows how medical practice

has been reshaped over the last two decades by the introduction of several

standardized protocols [Berg (1997)], and Ilana Lwy discusses the importance of randomized clinical trials for the introduction of new drugs in

general, and particularly in the treatment of desperate medical conditions

[Lowy

(2000)]. In both cases, it would seem reasonable to expect that

doctors would understand the reasoning that leads to stating that drug A is

preferable to drug B, or that exam Y should be requested when conditions

X, W and Z are present. Unfortunately, such expectations are often not

met, in practice, and Evidence-Based Medicine, for instance, capitalizes on

this insufficiency.

It is also possible to derive a hierarchy of sources of knowledge from

the interviews. At the highest level, as the most important source, lies

personal experience. Such experience includes bedside learning for medical

students. For doctors, it is more than hands-on, lived-through professional

experience, because such learning is often acquired by proxy through

continuous interaction with colleagues and even students. On the second

level, there is textual information. There are three subcategories in this level:

journal papers, textbooks and the internet. The internet is the most

dynamic and convenient source, although not necessarily the most reliable,

Downloaded from sss.sagepub.com at UNIV OF PITTSBURGH on March 25, 2015

846

Social Studies of Science 32/56

whilst books may be seen as inherently outdated, but also rock-solid when

it comes to proven knowledge. Papers occupy an intermediate position.

These findings are strongly similar to Flecks description of varieties of

scientific communication quoted in the beginning of this paper, with two

important exceptions: the first is obviously the internet, which was not

available in his time; the second and most intriguing is the lack of reference

to introductory handbooks. A possible explanation for this is that there are

actually no clear-cut differences between textbooks (vademecums) and

handbooks (manuals) in clinical medicine.

Although there is consensus among the interviewees about the characteristics of each of these textual forms, the relative ranking of the importance of the different forms varies considerably depending on who was

interviewed. Some of the younger doctors tended to rely more on the

internet than the older ones, but this was not always the rule. The most

enthusiastic user of the internet is Renato, who is in the mid-aged group.

Alberto, one of the elders, although not as enthusiastic as Renato, is less

critical about the internet than, for example, Luiza. Some recurrent

expressions also exhibit gradients, even within the same subcategory. For

example, footnotes in textbooks may be held superfluous, and the contents of latest papers may be regarded as unstable and risky. Both are

associated with the bookworm type of doctor, more concerned with

theory than practice, a stereotype with which none of the doctors wants to

be associated. Both the stereotype and its repulsiveness are strong evidence

of the epistemological primacy of experience for doctors. Doctors also

employ a clearly pragmatic, result-oriented approach, sometimes to such a

degree that they dispense altogether with the need to know the methodologies employed in the studies. By the same token, the doctors interviewed do not assign much importance to information from the so-called

basic sciences. They do, however, rely on personal and/or institutional

markers of epistemic authority as selection criteria. Foreign books in their

original language are more trusted than locally produced or translated

versions. As mentioned previously, the New England Journal of Medicine is

unanimously acknowledged as a symbol of excellence. Curiously, Christakis et al. (2000) claim that no such bias was observed in a study they

conducted, even though the artificial situation created in their experiment

was completely different from actual practice. Christakis and his colleagues

handed papers from two journals to their subjects. Through no coincidence, one of these journals was the NEJM. They disclosed the name

of the journal in some cases and not others, and subjects were asked to rate

them. After discussing limitations present in their research design, they

summarize their results with the following remarks:

These limitations prohibit us from concluding that journal attribution

bias does not exist. Nevertheless, our results are encouraging. They

suggest that given the opportunity and the dedication necessary to review

an article or abstract carefully, physicians regardless of their formal

training in epidemiology or biostatistics are able to read articles without

Downloaded from sss.sagepub.com at UNIV OF PITTSBURGH on March 25, 2015

Rochel de Camargo: Thought Style of Physicians

847

significant or large discernible bias based on publication source. [Christakis et al. (2000): 777]

The problem lies precisely in the fact that doctors lack the time to carefully

review everything, and they select papers based on the reputation of their

sources before they read them.

Finally, at the lowest level of the hierarchy lie passive oral communications: congresses, symposia, lectures, and meetings sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry on drugs being introduced (more on that later). These

are passive from the point of view of the interviewees, and should not be

confounded with learning by proxy, which is the result of systematic

interpersonal interaction that is tightly knit with professional practice.

Although there is divergence in the appreciation of this kind of activity

Marcos, Celia and Luiza explicitly dismiss it, while Luis considers it a

legitimate method of receiving predigested information in an easy way

even those who still considered it useful place it at the bottom level.

Training courses are occasionally mentioned, but usually as an impossibility due to the doctors busy lives. There is considerable overlap between

the levels of this hierarchy and the findings of Fernandez et al. (2000), who

studied similar sources of knowledge in medicine.

The last issue to be assessed in this section is the scepticism elicited in

the interviews. Medical scepticism is nothing new; in fact, therapeutic

scepticism is used as a label to identify a period in medical history (the late

19th century) during which most of the basic theoretical underpinnings of

modern medicine were in place, although no modern therapeutic options

were yet available. Doctors were then, as now, sceptical about their

pharmacopeia, yet had no other choice but to use them. Although presentday doctors may have more reason for trust than their 19th-century

counterparts, they also lack alternatives that would fully empower them to

pursue their mistrust to its fullest extent. Going back to the economic

argument previously presented, it should be noted that the production of

medical knowledge, or more precisely, the production of knowledge with

possible medical uses, is also part of the same economic dynamics. Since

the research is produced mainly by private sector companies with huge

economic interests at stake, there is a disproportionate concentration of

power on one side of the trade. These companies produce the knowledge,

funded through advertisements in the main journals. The journals also are

edited by large publishing companies, which are, in a sense, part of the

same sector of the economy. (The same can be said about the most

relevant textbooks.) Drug companies fund medical symposia and congresses and even subsidize individual doctors to attend such events. The

sponsors use such meetings to introduce new drugs, which have a curiously common mise-en-sc`ene: a renowned specialist is invited to present the

new drug, usually in a luxurious setting like a top-ranking hotel; during

the presentation, the invited authority never refers to the new drug by its

commercial brand, but only by its chemical name, although the venue is

usually literally covered with signs and posters prominently depicting the

Downloaded from sss.sagepub.com at UNIV OF PITTSBURGH on March 25, 2015

848

Social Studies of Science 32/56

products and the drug companys names. Finally, the most continuously

operated strategy involves the deployment of armies of marketing agents

from the pharmaceutical industry, who swarm around hospitals and clinics

and deliver free samples and gifts. Such practices have been demonstrated

to affect prescription patterns of physicians [Wazana (2000); DiNubile

(2000)]. There may be nothing inherently wrong with these activities,

but it is difficult to ignore the way medical knowledge is communicated in

and through the marketing practices of the pharmaceutical, equipment and

publishing industries. There is a solid body of literature produced in Latin

America, especially Brazil, from the early 1970s to the present [unfortunately, many of these sources, such as Cordeiro (1980), are not

translated into English], focusing on the so-called medical-industrial complex. This expression, coined after Eisenhowers famous remarks on the

alliance between military, political and economical interests in the USA, is

used to characterize the modern development of medicine in its relation to

industry. The analogy attempts to demonstrate that (a) medical needs are

not spontaneous, but heavily induced by the supply of health care services,

and that (b) economic interests tend to favour the deployment of such

services so as to maximize profit, with no direct relation to actual needs of

populations, especially the poorer sectors. This should not be mistaken for

a facile conspiracy theory: at issue is a configuration of mutually influential

institutional developments within capitalist societies. The medical profession, its schools, teaching hospitals, the pharmaceutical industry, the

medical equipment industry, technical publishing companies, all originated in different places and times, but developed as intimately interrelated

institutions, forging a network of strong social, economic and epistemic

links. Similar ideas are expressed by Blume, who interestingly also mentions Eisenhowers original expression [Blume (1992): 55].

Such an array of forces will inevitably introduce important biases into

medical knowledge and practice, as demonstrated by, among others, Stern

& Simes (1997), who found evidence of publication bias favouring publication of papers with positive evaluations of treatments; Friedberg et al.

(1999), who describe a similar situation with regard to cost-effectiveness

studies, in a paper that prompted an editorial comment urging more strict

guidelines for the submission of cost-effectiveness studies for publication

[Krimsky (1999)]; and Stelfox et al. (1998), who demonstrated a correlation between links to the pharmaceutical industry and sides taken on the

debate about a specific drug. While DiNubile (2000) deplores this situation

as a result of doctors being insufficiently sceptical, this does not seem to be

the case, necessarily. The sceptical stance of the interviewees in my study

was clearly evident and well argued. Almost all interviewees provided

examples compelling anecdotal evidence of cases in which guidelines

were not strictly followed and therapeutic success was achieved, anyway,

and they also described the converse situations in which strict adherence to

guidelines did not result in success. However, doctors lack resources

to fully pitch their scepticism against the massive forces of the medical

knowledge industry. This is not much different from the situation of the

Downloaded from sss.sagepub.com at UNIV OF PITTSBURGH on March 25, 2015

Rochel de Camargo: Thought Style of Physicians

849

hypothetical dissenter described by Latour [(1987): 21100], who keeps

challenging scientists claims, only to be finally silenced by the dazzling

array of resources that the latter can enrol in their support. No matter how

sceptical, in the end the doctor has no choice but to give in.

There are two possible objections that need to be addressed at this

point. First, it could be argued the interview responses do not describe the

doctors actual practices. Second, since the interviews address only general

practitioners, it could be argued that they do not necessarily represent the

views of specialists, particularly those in the more high-tech areas of

medicine.

With regard to the first objection, it should be noted that the interviewing strategy was designed so that respondents would not know the

actual goals of the research. The idea was to minimize the right answers

effect. Second, we can take into account the results from a second leg of

the study (the detailed results are not presented in this paper). Putting

together both legs of the study, a total of 24 interviewees from 2 different

institutions, facing 2 different interviewers, provided consistent responses.

Finally, even if interviewees were, in the worst possible case, grossly

misconstruing their opinions, beliefs and deeds in the interviews, that

misrepresentation would still be based upon presumably correct approaches, indicating the shared values that are actually more important to this

study.

With regard to the second objection, I would emphasize once again the

role

of the interviewees in forming opinions, given their pre-eminence both

as doctors and professors, particularly in the second role.

They contribute

heavily to shaping of the views of future doctors, general clinicians and

specialists alike. It should also be noted that, although the interviewees are

all professors of internal medicine, this does not mean that they have

not specialized in other fields. As a matter of fact, most of them are also

specialists, even in high-tech areas.

The exploratory nature of this study was mentioned at the beginning

of this paper. Additional research is necessary before the conclusions that

follow can be widely extrapolated. As noted, another set of interviews, still

being analysed, was conducted with Canadian professors, and an ethnographic phase of the study is still under way. Another research project,