Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Objective Correlative

Caricato da

manojkayastha3998Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Objective Correlative

Caricato da

manojkayastha3998Copyright:

Formati disponibili

What is the Objective Correlative?

The American Painter Washington Allston first used the term "objective correlative" about 1840, but T. S. Eliot

made it famous and revived it in an influential essay on Hamlet in the year 1919. Eliot writes:

The only way of expressing emotion in the form of art is by finding an 'objective correlative'; in

other words, a set of objects, a situation, a chain of events which shall be the formula of that

particular emotion; such that when the external facts, which must terminate in sensory experience,

are given, the emotion is immediately evoked. (qtd. in J. A. Cuddon's Dictionary of Literary

Terms, page 647)

If writers or poets or playwrights want to create an emotional reaction in the audience, they must find a combination

of images, objects, or description evoking the appropriate emotion. The source of the emotional reaction isn't in one

particular object, one particular image, or one particular word. Instead, the emotion originates in the combination of

these phenomena when they appear together.

For an example, consider the following scene in a hypothetical film. As the audience watches the movie, the scene

shows a dozen different people all dressed in black, holding umbrellas. The setting is a cemetery filled with cracked

gray headstones. The sky is darkening, and droplets of rain slide off the faces of stone angels like teardrops. A lone

widow raises her veil and as she takes off her wedding ring and sets it on the gravestone. Faint sobbing is audible

somewhere behind her in the crowd of mourners. As the widow starts to turn away, a break appears in the clouds.

From this gap in the gray sky, a single shaft of sunlight descends and falls down on a green spot near the grave,

where a single yellow marigold is blossoming. The rain droplets glitter like gold on the petals of the flower. Then

the scene ends, and the actor's names begin to scroll across the screen at the end of the movie.

Suppose I asked the viewers, "What was your emotional reaction after watching this scene?" Most (perhaps all) of

the watchers would say, "At first, the scene starts out really sad, but I felt new hope for the widow in spite of her

grief." Why do we all react the same way emotionally? The director provided no voiceover explaining that there's

still hope for the woman. No character actually states this. The scene never even directly states the widow herself

was sad at the beginning. So what specifically evoked the emotional reaction? If we look at the passage, we can't

identify any single object or word or thing that by itself would necessarily evokes hope. Sunlight could evoke pretty

much any positive emotion. A marigold by itself is pretty, but when we see one, we don't normally feel surges of

optimism. In the scene described above, our emotional reaction seems to originate not in one word or image or

phrase, but in the combination of all these things together, like a sort of emotional algebra. The objective correlative

is that formula for creating a specific emotional reaction merely by the presence of certain words, objects, or items

juxtaposed with each other.

The sum is greater than the parts, so to speak. In this case, "black clothes + umbrellas + cracked gray headstones +

darkening sky + rain droplets + faces of stone angels + veil + wedding ring + faint sobbing + turning away" is an

artistic formula that equates with a complex sense of sadness. When that complex sense of sadness is combined with

"turning away + break in clouds + single yellow marigold blossoming + shaft of sunlight + green spot of grass +

glittering raindrops + petals," the new ingredients now create a new emotional flavor: hope. Good artists intuitively

sense this symbolic or rhetorical potential.

T. S. Eliot suggests that, if a play or poem or narrative succeeds and inspires the right emotion, the creator has found

just the right objective correlative. If a particular scene seems heavy-handed, or it leaves the audience without an

emotional reaction, or it invokes the wrong emotion from the one appropriate for the scene, that particular objective

correlative doesn't work. For extended literary discussion, see Eliseo Vivas' "The Objective Correlative of T. S.

Eliot," reprinted in Critiques and Essays in Criticism, ed. Robert W. Stallman (1949).

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- How Do I Get Started?: Figurative LanguageDocumento13 pagineHow Do I Get Started?: Figurative LanguageJayanth VenkateshNessuna valutazione finora

- Emily Dickinson's PoetryDocumento5 pagineEmily Dickinson's PoetrytayibaNessuna valutazione finora

- Democracy As A Way of LifeDocumento5 pagineDemocracy As A Way of LifeDipankar GhoshNessuna valutazione finora

- Oedipus Rex as an Ideal Greek TragedyDocumento3 pagineOedipus Rex as an Ideal Greek TragedyGlory ChrysoliteNessuna valutazione finora

- HEC project improves English teaching in PakistanDocumento15 pagineHEC project improves English teaching in PakistanMuhammad HaseebNessuna valutazione finora

- Code HeroDocumento6 pagineCode HeroAngie Stefanny Cortés PérezNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction About The PoetDocumento3 pagineIntroduction About The PoetSr Chandrodaya JNessuna valutazione finora

- Poetic FormsDocumento3 paginePoetic FormsaekulakNessuna valutazione finora

- The Great Wall of China Report PaperDocumento2 pagineThe Great Wall of China Report Paperapi-248622707Nessuna valutazione finora

- ICJ and International LawDocumento1 paginaICJ and International LawCEMA2009Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sultan: Abdullah 1Documento20 pagineSultan: Abdullah 1Kumaresan RamalingamNessuna valutazione finora

- Walt Whitman Biography and PoetryDocumento10 pagineWalt Whitman Biography and PoetryScarlet Bars KinderNessuna valutazione finora

- Session-2021-22: Assignment Subject-ENGL 305: Modern Poetry (English) Submitted ToDocumento25 pagineSession-2021-22: Assignment Subject-ENGL 305: Modern Poetry (English) Submitted ToGargi MishraNessuna valutazione finora

- Preface To Lyrical Ballads Critical AnalysisDocumento3 paginePreface To Lyrical Ballads Critical AnalysisZeeshanNessuna valutazione finora

- Redefining Poetry The Preface To Lyrical PDFDocumento3 pagineRedefining Poetry The Preface To Lyrical PDFBindu KarmakarNessuna valutazione finora

- Mill+Goblin MarketDocumento6 pagineMill+Goblin MarketBarbara SantinNessuna valutazione finora

- 26 Pio 09Documento1 pagina26 Pio 09greatbongNessuna valutazione finora

- The Waste Land Section IDocumento5 pagineThe Waste Land Section ILinaNessuna valutazione finora

- 06 BRichards, Practical CriticismDocumento4 pagine06 BRichards, Practical Criticismjhapte02Nessuna valutazione finora

- Emily Dickinson'S Poems: Narrow Fellow in The Grass (The Snake) - in All These Poems, Dickinson Uses The Nature As ADocumento3 pagineEmily Dickinson'S Poems: Narrow Fellow in The Grass (The Snake) - in All These Poems, Dickinson Uses The Nature As AVanessa VelascoNessuna valutazione finora

- Level of Analysis-Rourke12e Sample Ch03Documento37 pagineLevel of Analysis-Rourke12e Sample Ch03teibs000% (1)

- Marxism in The StrangerDocumento9 pagineMarxism in The Strangernikpreet45Nessuna valutazione finora

- New Thematic Concerns of T.S.eliotDocumento3 pagineNew Thematic Concerns of T.S.eliotSourabh PorelNessuna valutazione finora

- Modern Poetry and W B Yeats An Overview PDFDocumento14 pagineModern Poetry and W B Yeats An Overview PDFVICKYNessuna valutazione finora

- Jane Austens Art of CharacterizationDocumento6 pagineJane Austens Art of CharacterizationsomishahNessuna valutazione finora

- Nissim EzekielDocumento4 pagineNissim EzekielNHNessuna valutazione finora

- The Qualities of A Good Translator, by Dr. Shadia Yousef BanjarDocumento12 pagineThe Qualities of A Good Translator, by Dr. Shadia Yousef BanjarDr. ShadiaNessuna valutazione finora

- John Milton 2012 7Documento516 pagineJohn Milton 2012 7Ricardo Araiza SepulvedaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood Dante Gabriel RossettiDocumento14 pagineThe Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood Dante Gabriel RossettiAjay RawatNessuna valutazione finora

- Epic similes in Paradise Lost Book IDocumento2 pagineEpic similes in Paradise Lost Book INishant SaumyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Naturalism Curent LiterarDocumento7 pagineNaturalism Curent LiterarAlina-Alexandra CaprianNessuna valutazione finora

- Analysis of The Hollow Men in The Light of Tradition and Individual TalentDocumento9 pagineAnalysis of The Hollow Men in The Light of Tradition and Individual TalentKamal HossainNessuna valutazione finora

- Pessimism in Victorian PoetryDocumento6 paginePessimism in Victorian Poetryzaid aliNessuna valutazione finora

- Post Modern Indian Theatre - Ratan Thiyam's Silent War On WarDocumento9 paginePost Modern Indian Theatre - Ratan Thiyam's Silent War On Warbhooshan japeNessuna valutazione finora

- Bhuter Naach-Analysing TheDocumento4 pagineBhuter Naach-Analysing Thescribdguru2Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Rise of Puritanism in The Age of MiltonDocumento5 pagineThe Rise of Puritanism in The Age of MiltonIftikhar100% (1)

- Preface CollinsDocumento3 paginePreface CollinsMercedes IbizaNessuna valutazione finora

- One Liner of "Liberal Humanism"Documento2 pagineOne Liner of "Liberal Humanism"Amir NazirNessuna valutazione finora

- Academic communication: An analysis of T.S. Eliot's "Tradition and the Individual TalentDocumento3 pagineAcademic communication: An analysis of T.S. Eliot's "Tradition and the Individual TalentEdificator BroNessuna valutazione finora

- A Note of Integration in Dattani's Final Solutions Against Religious DifferentiationDocumento10 pagineA Note of Integration in Dattani's Final Solutions Against Religious DifferentiationDr. Prakash BhaduryNessuna valutazione finora

- Mark Twain Biography and Writing Style PDFDocumento5 pagineMark Twain Biography and Writing Style PDFAyesha RabbaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Preface To ShakespeareDocumento3 paginePreface To ShakespeareShweta kashyapNessuna valutazione finora

- Victorian+Lit +charDocumento2 pagineVictorian+Lit +charCristina DoroșNessuna valutazione finora

- Poetry AnalysysDocumento52 paginePoetry AnalysysRamanasarmaNessuna valutazione finora

- A Brief Guide To Confessional PoetryDocumento1 paginaA Brief Guide To Confessional PoetryFerhad GirêşêranNessuna valutazione finora

- Atticus FinchDocumento4 pagineAtticus FinchDisha Aakriti BhatnagarNessuna valutazione finora

- America Scholar SummaryDocumento2 pagineAmerica Scholar SummaryVrinda Dhongle100% (2)

- Aristotle Tragedy Vs Modern Tragedy DramaDocumento9 pagineAristotle Tragedy Vs Modern Tragedy DramaBisma JamilNessuna valutazione finora

- The Romantic AgeDocumento5 pagineThe Romantic AgeTANBIR RAHAMANNessuna valutazione finora

- Being Free of Violence and The Threat of Violence: Violence and The Threat of ViolenceDocumento9 pagineBeing Free of Violence and The Threat of Violence: Violence and The Threat of ViolenceReca Jane CañaNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 Ideas Mentioned in Yeats's Diary Record, Quoted by David A. Ross in His Critical Companion To WillianDocumento2 pagine1 Ideas Mentioned in Yeats's Diary Record, Quoted by David A. Ross in His Critical Companion To WillianIsabela ChioveanuNessuna valutazione finora

- Robert FrostDocumento12 pagineRobert Frostjobanjunea0% (1)

- Classical Poetry: BS EnglishDocumento113 pagineClassical Poetry: BS EnglishTalha Khokhar100% (1)

- Themes of American PoetryDocumento2 pagineThemes of American PoetryHajra ZahidNessuna valutazione finora

- Lyrical BalladsDocumento3 pagineLyrical Balladsaamu19808951Nessuna valutazione finora

- TranscendentalismDocumento11 pagineTranscendentalismapi-320180050Nessuna valutazione finora

- Diasporic Writing QuestionsDocumento31 pagineDiasporic Writing QuestionsMEIMOONA HUSNAIN100% (1)

- Summary of 'Ash Wednesday': T.S. Eliot, in Full Thomas Stearns Eliot, (Born September 26Documento7 pagineSummary of 'Ash Wednesday': T.S. Eliot, in Full Thomas Stearns Eliot, (Born September 26Ton TonNessuna valutazione finora

- Gale Researcher Guide for: William Blake's Songs of Innocence and of ExperienceDa EverandGale Researcher Guide for: William Blake's Songs of Innocence and of ExperienceNessuna valutazione finora

- 22 March 2012Documento4 pagine22 March 2012manojkayastha3998Nessuna valutazione finora

- Relevant Articles of ConstitutionDocumento5 pagineRelevant Articles of Constitutionmanojkayastha3998Nessuna valutazione finora

- Law LLB 2062011Documento378 pagineLaw LLB 2062011manojkayastha3998Nessuna valutazione finora

- Objective CorrelativeDocumento1 paginaObjective Correlativemanojkayastha3998Nessuna valutazione finora

- Desirable: - Knowledge of Hindi.: Employment NoticeDocumento5 pagineDesirable: - Knowledge of Hindi.: Employment NoticeNagender Singh RajputNessuna valutazione finora

- Arnold TouchstoneDocumento5 pagineArnold Touchstonemanojkayastha3998Nessuna valutazione finora

- TIA Selection Tool: Release Notes V2022.05Documento10 pagineTIA Selection Tool: Release Notes V2022.05Patil Amol PandurangNessuna valutazione finora

- Chap 2 Debussy - LifejacketsDocumento7 pagineChap 2 Debussy - LifejacketsMc LiviuNessuna valutazione finora

- Certificate Testing ResultsDocumento1 paginaCertificate Testing ResultsNisarg PandyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Arm BathDocumento18 pagineArm Bathddivyasharma12Nessuna valutazione finora

- Fake News Poems by Martin Ott Book PreviewDocumento21 pagineFake News Poems by Martin Ott Book PreviewBlazeVOX [books]Nessuna valutazione finora

- Final Decision W - Cover Letter, 7-14-22Documento19 pagineFinal Decision W - Cover Letter, 7-14-22Helen BennettNessuna valutazione finora

- SECTION 303-06 Starting SystemDocumento8 pagineSECTION 303-06 Starting SystemTuan TranNessuna valutazione finora

- Math 202: Di Fferential Equations: Course DescriptionDocumento2 pagineMath 202: Di Fferential Equations: Course DescriptionNyannue FlomoNessuna valutazione finora

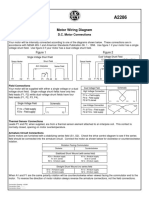

- Motor Wiring Diagram: D.C. Motor ConnectionsDocumento1 paginaMotor Wiring Diagram: D.C. Motor Connectionsczds6594Nessuna valutazione finora

- CP 343-1Documento23 pagineCP 343-1Yahya AdamNessuna valutazione finora

- Hypophosphatemic Rickets: Etiology, Clinical Features and TreatmentDocumento6 pagineHypophosphatemic Rickets: Etiology, Clinical Features and TreatmentDeysi Blanco CohuoNessuna valutazione finora

- Drugs Pharmacy BooksList2011 UBPStDocumento10 pagineDrugs Pharmacy BooksList2011 UBPStdepardieu1973Nessuna valutazione finora

- O2 Orthodontic Lab Catalog PDFDocumento20 pagineO2 Orthodontic Lab Catalog PDFplayer osamaNessuna valutazione finora

- QP (2016) 2Documento1 paginaQP (2016) 2pedro carrapicoNessuna valutazione finora

- VT6050 VT6010 QuickGuide ENDocumento19 pagineVT6050 VT6010 QuickGuide ENPriyank KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- LSUBL6432ADocumento4 pagineLSUBL6432ATotoxaHCNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction To Finite Element Methods (2001) (En) (489s)Documento489 pagineIntroduction To Finite Element Methods (2001) (En) (489s)green77parkNessuna valutazione finora

- 2018-04-12 List Mold TVSDocumento5 pagine2018-04-12 List Mold TVSFerlyn ValentineNessuna valutazione finora

- Parts of ShipDocumento6 pagineParts of ShipJaime RodriguesNessuna valutazione finora

- Update On The Management of Acute Pancreatitis.52Documento7 pagineUpdate On The Management of Acute Pancreatitis.52Sebastian DeMarinoNessuna valutazione finora

- Traffic Violation Monitoring with RFIDDocumento59 pagineTraffic Violation Monitoring with RFIDShrëyãs NàtrájNessuna valutazione finora

- Activities and Assessments:: ASSIGNMENT (SUBMIT Your Answers at EDMODO Assignment Section)Documento5 pagineActivities and Assessments:: ASSIGNMENT (SUBMIT Your Answers at EDMODO Assignment Section)Quen CuestaNessuna valutazione finora

- Chemistry of FormazanDocumento36 pagineChemistry of FormazanEsteban ArayaNessuna valutazione finora

- 07.03.09 Chest Physiotherapy PDFDocumento9 pagine07.03.09 Chest Physiotherapy PDFRakesh KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Feline DermatologyDocumento55 pagineFeline DermatologySilviuNessuna valutazione finora

- Revolutionizing Energy Harvesting Harnessing Ambient Solar Energy For Enhanced Electric Power GenerationDocumento14 pagineRevolutionizing Energy Harvesting Harnessing Ambient Solar Energy For Enhanced Electric Power GenerationKIU PUBLICATION AND EXTENSIONNessuna valutazione finora

- DR-M260 User Manual ENDocumento87 pagineDR-M260 User Manual ENMasa NourNessuna valutazione finora

- Seed SavingDocumento21 pagineSeed SavingElectroPig Von FökkenGrüüven100% (2)

- CG Module 1 NotesDocumento64 pagineCG Module 1 Notesmanjot singhNessuna valutazione finora

- 3GPP TS 36.306Documento131 pagine3GPP TS 36.306Tuan DaoNessuna valutazione finora