Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

One Last Time PDF

Caricato da

superultimateamazingTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

One Last Time PDF

Caricato da

superultimateamazingCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Postcolonial Text, Vol 5, No 2 (2009)

Gender, Language, and Identity in Dogeaters: A

Postcolonial Critique

Savitri Ashok

Middle Tennessee State University

Gender Oppression and Postcoloniality

Jessica Hagedorns 1990 novel is set in postcolonial Philippines, during

the years of nation building and martial law under President Ferdinand

Marcos, who ruled Philippines from 1965 to 1986. Nationalism, as it

appears in the revisionary history of Dogeaters, continues the oppression

of colonialism by remolding the binary paradigm on which the colonial

conquests were based. If the imperialist patriarchy justified its colonizing

endeavors by presenting the conquered as the different, savage, inferior

and exotic other, nationalism involves a concerted attempt at the recovery

of the manhood lost in colonization, projecting woman as the other, to be

gazed at, tamed, conquered, and enjoyed. Nation building in postcolonial

Philippines becomes a search for recovering a lost masculinity for the

indigenous men of power. Hagedorns feminism opens up a site in the text

for a succinct critique of the anti-woman tendencies inhering in

nationalism. The patriarchal, forked imaging of the woman as the virgin or

the whore is replicated in some of the novels women-characters. The

female figures in Filipino postcolonial society portrayed by Hagedorn

embody the patriarchal contradictions [and] bring together the

dichotomized icons of idealized femininity and degraded whoredom, of

feminine plenitude and feminine lack (Chang 639-40). Zenaida, Mother

of a whore and a whore of a mother (Hagedorn, Dogeaters 205) is a

disembodied deviant, impure femininity (Chang 640), appearing in the

background haze of the novel, a ghostly figure trampled by patriarchy.

If, as Carol Hanisch points out, the personal is political, and if the

sexual relations between men and women carry a political implication,

then the disarray in the power equations of the genders, within and outside

the institution of marriage in Dogeaters, points to a much larger national

malaise. The woman question, foregrounded in the novel, is germane to

a postcolonial text, since the dialectic of the sexes involves another variant

of the same hegemonic mythology (positing one group as superior to

another) that underlies colonial expansions. Women, as a sub-culture,

always removed from the reigning paradigm of patriarchy (thrice

colonized in the process of history, first by the patriarchy within and then

by the colonizers from without and then again by the nation-builders),

become the special focus of Hagedorns postcolonial perspective. That

Hagedorn chose to have about a dozen stories in the text with women as

central characters shows her investment in this issue.

As patriarchy is engaged in the task of remolding its machismo

identity after the emasculating assault of colonialism, women become

further removed from the political process itself. The only way that

women can feel an illusion of power is by collusion with patriarchy, as in

the case of the Generals wife, the first lady in the novel, the Iron

butterfly. As Juliana Chang notes, female figures like the first lady and

the talk-show host Cora Camacho create and embody spectacle in the

service of the state (642), ideal figures in the eyes of a patriarchal state,

seeking and getting patriarchal approbation. The first lady in the novel,

based on Imelda Marcos, the wife of former president Ferdinand Marcos,

interprets womens willingness to participate in beauty contests as a

gesture of nationalist spirit and in effect colludes in the replacement of the

imperialist gaze with the nationalist gaze. The attempt to push women

into beauty contests and making this participation a signal of patriotism

depletes women of their subject positions by turning them into objects of

gaze. Transformed into sexual locations where masculinity is tested and

authenticated, women, as Dogeaters demonstrates, are encouraged, in the

name of nationalism, to become objects. The gaze, as Ann Kaplan

suggests, is a hierarchical act, empowering the agent and emaciating the

object: while look is a process, a relation (xvi), gaze connotes an

active subject versus a passive object (22), essentially disempowering the

person gazed at. The beauty contests are sites of this power play that

authenticate male power and deplete womens agency.

The stickiness of female consent for male violences (Lee 98),

perceived in the first ladys endorsement of beauty pageants, is also seen

in the self-mortifying, ascetic Leonor Ledesma who atones for the murders

and acts of cold-blooded brutality committed by her husband, the General,

and in a sense absolves him and sets him free of compunction to continue

his spree of violence:

Upstairs, the Generals wife tosses and turns on her spartan bed, a regulation army cot

she once asked her husband to send over from one of the barracks. The General found

her request perfectly understandable, in light of her devotion to an austere, forbidding

God and her earnest struggles to earn sainthood through denial. (67)

In her ascetic penance that is tantamount to tacit consent, Leonor functions

as an enabler and is guilty of complicity with her brutal husband. In a

masculine state where violence and brutality are normalized, how does a

woman negotiate her life and come to peace with her conscience?

Leonors austerity is not merely a survival strategy; her religion provides

the sacrificial fire in which the General finds purgation for his repeated

acts of violence. In contrast, Daisy Avila is certainly not a consenting

female. Her opposition to male brutality takes the form of violence. As

Leonor immerses herself in ritualistic stoicism, Daisy picks up the tool of

patriarchal violence to fight this very same type of violence. Rejecting the

beauty halo, much to the first ladys chagrin, on a nationally broadcast talk

2

Postcolonial Text Vol 5 No 2 (2009)

show Daisy denounces beauty contests as a giant step backward for all

women (109). The fact that Daisy becomes Aurora, that the beauty

transforms into a rebel fighting the nation builders, indicates the intensity

of Hagedorns fierce feminism. As Aurora marches into the streets with

grenades hidden in her dress, she manifests a feminist challenge to the

heavily male-centered nationalist politics. By choosing violence as her

tool, she levels the political playing field.

However, the gang rape of Daisy/Aurora shows that politics is still an

unequal field. Central to the feminist politics of the novel, Auroras

violation by the nation builders functions as a trope for the defilement and

dehumanization of the othering process with which imperialist ideology

rationalized its rape of other lands and women. Auroras rape at the hands

of the Filipino national leaders makes a statement about the warped power

structure in postcolonial Philippines; it suggests that instead of setting

right the wrongs let loose by the colonizing patriarchs, the national

patriarchy continues the colonization of women by desecrating the female

body and by degrading women to mere bodies. The gang rape, a collective

male act of violation of the female body, is performed literally in the

text, to the background voice-overs from the favorite radio show of the

Filipinos. As one man rapes Daisy, others witness it. This performative

display of violence on the female body, carried out by the countrys

power-wielders contains, besides its pornographic import, the ominous

implication that it will be told and retold as a moral tale to threaten women

into submission and subjugation. Susan Brownmillers claim that both the

possibility and actuality of rape are political tools perpetuating male

dominion over women by force (209) is very much to the point here.

The disruption of the body politic, set in motion by colonization and

perpetuated in the neocolonialist endeavors of the nationalists, is thus

inscribed in the text as an invasion, a specular violence, and a diseased

eruption of the body erotic. The violence of the colonizer, as the text

depicts, is perpetuated in the ways in which women are treated in a

postcolonial regime. Postcolonial critic Ania Loomba rightly notes that the

imagining of a nation is profoundly gendered and that [n]ational

fantasies, be they colonial, anti-colonial or postcolonial also lay upon the

connections between women, land or nations (215). Daisys invaded

body carries all the burden of her countrys historical nightmare, just as

Baby Alacrans body breaks into undiagnosable eruptions mirroring the

distortions occurring in a country and its culture. The daughter of an

influential, highly placed businessman in the Philippines a wheeldealer, ruthless and ambitious (20) Baby Alacran, it appears, bears the

burden of her fathers callousness and hypocrisy. The relationship

between the female body and the body politic is made clear in the words

of the Alacrans family doctor, Dr. Katigbak, who conflates Baby

Alacrans bodily mishaps with the lands malformations: Think of your

daughters body as a landscape, a tropical jungle whose moistness breeds

fungus, like moss on trees (29).

Postcolonial Text Vol 5 No 2 (2009)

If Daisy Avila and Baby Alacran enact the explosive violence of

neocolonial, nationalist patriarchy, Lola Narcisa embodies what the

reigning ideology has suppressed. Described by Rio, one of the narrators,

as unseen and silent, Lola Narcisa, Rios Asian grandmother, typifies what

Gayatri Spivak refers to as the subaltern who cannot speak and who is

deeply in shadow (2203). Hagedorn enacts her silence and invisibility in

the limited textual space that she assigns to her. However, in a brilliant

postcolonial gesture, Hagedorn gives substance to the shadow and gives

her a voice. Transforming a Hollywood movie sequence from A Place in

the Sun into an ironic retelling in the imagination of Rio (making way for

a teasing mise-en-abyme: for isnt the entire text a product of the writers

imagination?), Rio imagines Lola Narcisa bending over my grandfathers

bed like Jane [Wyman], an angel of mercy whispering so softly in his ear

that none of us can make out what she is saying (16). The silent woman

is given a strong voice as she screams, DONT TOUCH HIM (16-17).

Ultimately, it is the reader who is stunned that the shriveled brown

woman has so loudly and finally spoken (17). Indeed, Hagedorn makes

the subaltern speak in Rios fantasy.

Like Lola Narcisa and Daisy Avila, Lolita Luna, the film actress, is

another woman in the text caught in a nexus of suppression, ownership,

and violence. Her life, reduced to mere sexuality by her two loversan

Englishman with colonial obsessions (170) and General Ledesmo, the

postcolonial military leaderdramatizes the predicament of women in

colonial and postcolonial societies. Lolita Lunas body encodes the

national body, trapped by two forms of patriarchal power: colonialism and

nationalism. Like her country, she is objectified, commodified and

exoticized and is brought totally under control. The ironic title of the

chapter, Movie Star (170), depicts the contrast between her glamorous

faade and the reality of her defilement. This is rendered poignant by the

suggested association that very often the colonized other, nation and

woman, was an object of exoticizing gaze while being subjected to

colonial rule. That Lolita Lunas life is at the mercy of the ruling men, as

the nations existence is, is depicted in the anxiety she expresses over her

possible death by accident (174). The theme of migration central to

postcolonial literature surfaces in her desire to buy her own ticket out of

the country (177).

Language, Structure, and Counter-Discourse

The migrant yearnings in the novel testify to the feeling of homelessness

characteristic of the postcolonial condition. An expatriate writer herself,

Hagedorn writes her novel with a double vision afforded by the hybrid

nature of postcoloniality. However, the reality of her expatriation to

America and the fact of her writing in English, some critics argue, testify

to the writers collusion with the colonizer. They suggest that, instead of

functioning as an oppositional text, the novel subscribes to the canon,

aiming to please the western world: Conflating heresy and orthodoxy,

Postcolonial Text Vol 5 No 2 (2009)

Hagedorns Dogeaters possesses the qualities of a canonical text in the

makingfor the multiculturati (5), says San Juan Jr. In a similar vein,

DAlpuget notes that the language variations in the novel become exotic

and that [t]he exoticisms become tiresome, more a nervous tic than a

desire to make a connection across the gulf of culture (38). The

assumption behind such criticism seems to be that Hagedorns required

goal is to bridge the gulf of culture by putting Philippines on a platter for

the west. However, as Gladys Nubla points out, the novel works in a

transnational space, apart from both national abstractions (201) and is

linked to the marginalized multitudes erased or merely glossed over in

these abstractions. Rio, much like Hagedorn, is negotiating two worlds in

her search for identity, and the schizophrenia of the postcolonial condition

becomes clear in the clash of worlds and the combining of idioms. Rather

than identifying with one nations citizenry or the other in absolute terms,

as Melinda L. De Jesus notes, the novel uses the figure of the mestizo,

an important modality in Filipino fiction, to discuss aspects of identity

formation and liminality (226). Victor Mendozas insight that the novel

offers the possibility of assembling political associations . . . not

according to Philippine nationalist terms but according to something

altogether exterior to the discourse of the nation-state (816) is precise.

What we get in the novel is a third space, not traceable to two originary

contexts, but which enables other positions to emerge (Bhabha, The

Third Space 211). One could say that identity, as portrayed by Hagedorn,

cuts through bicultural politics and is liminal and substantiates the claim

that the project of decolonization is carried forth in the postcolonial site

but may equally be deployed by immigrant and diasporic populations

(Lowe 108). Expatriate writers like Hagedorn carry the postcolonial site

into the empires mainland.

As an exile living in the United States, speaking, reclaiming, and

refiguring selfs and nations histories in the English language, Hagedorn

raises the issue of colonial mimicry. The colonial subjects mimicry, as we

know from Bhabha, is at once resemblance and menace (Location 86),

whereby the reappropriated language becomes a rebellious tool. Bhabha

suggests that the colonized native, on whom the impact of the British or

any other colonial enculturation makes an indelible mark, uses English but

repeats it with a difference. This colonial mimicry bordering on mockery

of which Hagedorns writing in English is a superb example becomes a

hybrid site. The nativizing differences and the lexical interpolations that

compose the peppered style of Dogeaters destabilize the homogenous

standard English of colonial discourse and become simultaneously

resemblance and menace.

The authors of The Empire Writes Back perceptively note that

English was made . . . central to the cultural enterprise of Empire (3).

Critics like Viswanathan concur with the observation that English played a

big role in inducing compliance in native subjects (93). Hence, a

postcolonial writer who uses English to re-present his/her reality is

engaged, according to Boehmer, in the process of cleaving from, moving

5

Postcolonial Text Vol 5 No 2 (2009)

away from colonial definitions, transgressing the boundaries of colonialist

discourse; and in order to effect this, cleaving to: borrowing, taking over,

or appropriating the ideological, linguistic and textual forms of the

colonial power (106-07). This hybrid cleaving results in an anti-colonial

mimicry that deals syntagmatically with a range of differential

knowledges and positionalities that both estrange . . . identity and

produce new forms of knowledge, new modes of differentiation, new sites

of power (Bhabha, Location 120). Salman Rushdie, another example of

the artist as migr, states his ambivalence regarding the use of English:

Those of us who do use English do so in spite of our ambiguity towards it, or perhaps

because of that, perhaps because we can find in that linguistic struggle a reflection of

other struggles taking place in the real world, struggles between the cultures within

ourselves . . . To conquer English may be to complete the process of making

ourselves free. (17)

Hagedorns use of English is a hybrid site of creative transformation and

appropriation of the language. English as used by Hagedorn becomes

unintelligible at times to a western reader due to the Filipino infusions into

the language. However, the title of the novel, Dogeaters, is an

Americanism, a depreciatory term used by the colonists to refer to the

Filipinos. Hagedorn follows up this title with a series of diverse, poignant

stories that expose the narrowness of the titular label. Also, hybridizing

the English language, and breaking the rules of linear narration and

semantic purity inhering in colonial narratives, Hagedorn transforms

English into something other than itself. Opting for complexity and

obscurity in style and deprioritizing clarity, Hagedorn refuses to be a

colonial subject. For, as Trinh Minh-Ha observes, Clarity [in style] is a

means of subjection . . . (16).

I set out to write on my own terms and in the English I reclaim as

postcolonial Filipino, Hagedorn states in her introduction to Danger and

Beauty (xi). Splitting open the closure of standard American English by

ruptures and indeterminacies brought in by traces of tagalog (the

vernacular), tsismis (local gossip), radio shows and nonsensical

vocabulary, Hagedorns postcolonial English breathes the very hybridity

and confused complexity of the characters whose tales it tells. According

to Helena Grice, Hagedorn blends feminist and/or historical writing with

experimental modes of narration, which are themselves sources of creative

and oppositional energy (181). Vital to the experimental style of

Dogeaters is gossip, which is an antifiguration of narrative (Lowe

101). Both Lowe and Mendoza observe that official history comes from

the unitary standpoint of the state (Lowe 113, Mendoza 1); gossip feeding

on official history erases the binary of legitimacy/illegitimacy (Lowe 113).

Tsismis/gossip is a stylistic tool that contests the unitary history of

hierarchical depictions. As Patricia Meyer Spacks contends, Female

gossip . . . functions as a mode of feeling . . . of undermining public

rigidities and asserting integrity, of discovering of means of agency for

Postcolonial Text Vol 5 No 2 (2009)

women (170). In the novel, tsismis or gossip primarily emanates from

Rio, Pucho, and their circle, and is mostly confined to women. As Pucho

says, tsismis is the center of our lives (166). One woman tells another,

sit down lets make tsismis (55). Sarita Sees observation that

Dogeaters deprioritizes any monumental notion of history by deferring

instead to gossiptsismisas a centripetal, destabilizing structure for the

novel (47) is very much to the point here.

Besides providing stable, unitary narratives of history, colonialism

also had Christian proselytization at the center of its expansionist

enterprise. Contesting the colonial legacy of religion by deliberately

committing blasphemy, Hagedorn makes brilliant use of Filipino English

to disrupt the Lords Prayer in the final kundiman, or prayer (Dogeaters

250-51). Hagedorns kundiman reenacts the quintessential postcolonial

situation of Caliban throwing the language of his conqueror, Prospero,

back at him through his acquired gift of the English curse. Sacrilegious

mimicry becomes a tool of protest and self-affirmation. In the kundiman,

Hagedorn fulfills Trinh Minh-Has prerequisite for a postcolonial nativewoman-writer: that she who works at unlearning the dominant language

of civilized missionaries also has to learn how to un-write and write

anew (148).

I would curse you in Warray, Ilocano, Tagalog, Spanish, English,

Portuguese and Mandarin: I would curse you but I chose to love you

instead. Amor, amas, amatis, amant, give us this day our daily bread

(250), Hagedorn asserts in the kundiman, which is a prayer to Mary. In a

sublime subversion of the Lords prayer, nation and woman become one

as Mary is described as defiled, belittled, and diminished (250). An

array of violent imagesdeath, blood, daggers, arrows, slingshots,

grenades, despair, longing, ignited flesh, exploded flesh (251)add up to

conjure the epistemic violence to which the nation has been subjected. The

prayer trails to a close with forgive us our sins, but not theirs (251), the

ambiguous theirs perhaps alluding not only to the destroyers of a

culture, the colonists, but also to their latter-day avatars, the nationalists.

Bhabhas observation that [b]lasphemy is not simply a

misrepresentation of the sacred by the secular but is a moment when the

subject matter or the content of a cultural tradition is being overwhelmed,

or alienated, in the act of translation (Location 225) is crystallized in the

kundiman. A translated English prayer, a love song, a blasphemous curse

all rolled into one, the kundiman subverts religion and language, two

colonial bequests, in one fell swoop. The language of the colonizer (a

metonym for the educational rationale put forward for colonial

enterprises) and colonial religion (missionary work was invoked for

justifying colonialism) are reappropriated as native assets in this superb

subversion.

The voice of the prayer is ambiguous. In one of her interviews,

Hagedorn talks about the rage and love in the prayer and then suggests the

voice could be hers:

Postcolonial Text Vol 5 No 2 (2009)

Theres a lot of brutality in Dogeaters, and I think that especially with the suffering

that the character Daisy goes through and the loss of the senator and all the other

people who die or are tortured, and just the daily suffering of the poor there, which is

enormous, the Philippines is still a beautiful country and I wanted somehow to

convey that. So I decided originally that the Kundiman section was going to be the

grandmothers prayer . . . But I thought, No, I want to even lift it above a specific

characters voice, and maybe its my voice that speaks at the end.

Undeniably, it is a womans voice.

If the kundiman is a quintessential female postcolonial text, the four

epigraphs from Jean Mallat, the nineteenth-century historian of the

Philippines, constitute a quintessential colonial text. Official history,

which presumes its own omniscience of the conquered other, is seen most

explicitly in Mallat, whose words Hagedorn prefaces to her own

scrambled, fictional and idiosyncratic visions of history. In contrast to

Hagedorns narrative, there is a solid certainty in Mallats record of the

Filipinos. The confident and condescending tone with which he

characterizes a whole group of native others seems to arise out of what

Said refers to as the culturally hegemonic idea of Europe that posits

European identity as a superior one in comparison with all the nonEuropean peoples and cultures (7). Mallats colonial text defines the

Filipinos as a monolithic entity, a seamless culture of sleeping natives

without conscience. This epigraph condenses the binary paradigms

(nature/culture, instinct/reason, and emotion/reason) operative in colonial

ideology. Mallats book also shows the direction of the imperialist,

historical argument that the natives were unchristian savages who needed

to be reformed by the missionary work of the Europeans. The authoritative

and homogenizing voice of this colonial text is set in contrast with the

contrapuntal, plural retelling of Hagedorns varied histories. The

juxtapositions of official histories with local gossip and blasphemous

retellings show the artist as a political provocateur. As Marie-Therese

Sulit notes, Dogeaters questions the systems of dominance that structure

the Philippines, defining them in masculine ways that her characters

redefine with the infusion of the feminine, a strategy that moves the sacred

imagery of Catholics into more secular, albeit perhaps blasphemous

space (146).

Identity and the New Nation

Hagedorns aesthetic choice to incorporate colonial texts (Mallat,

McKinleys address etc.) in her fiction marks Dogeaters as a definitive

postcolonial tale attempting to retell history (and herstory). In the end,

however, the text subverts its own pretense to finality of meaning when

Pucho unwrites/rewrites Rios version of herstory. By making Pucho refer

to the entire text as the work of a crazy imagination (249) and by

making her proclaim, Rio, youve got it all wrong (248), Hagedorn

gives a new spin to the already ambiguous text, hinting that there could be

other versions to the story that she has narrated painstakingly, if

scatteringly, thus far; and that Rio, Hagedorns alter ego perhaps, can at

8

Postcolonial Text Vol 5 No 2 (2009)

best present an incomplete and questionable version of an elusive truth

and at worst tell an intelektwal (248) lie. Pucho, Rios resisting reader,

problematizes what the text intends to represent. Her resistance is the

texts courageous confrontation with its own incompleteness. It points to

the textuality and constructed nature of all narrativescanonical, colonial

histories includedand to the constructed nature of our identities. It

certainly points to pure Filipino identity as a myth.

Rio, the female protagonist from whom we hear much of the

narration, shows Filipino subjectivity as evolving out of a complex

relationship with a colonizing culture. San Juan notes that most Filipinos

have been so profoundly Americanized that the claim of an autonomous

and distinctive identity sounds like a plea bargaining after summary

conviction (5). Identity, for a postcolonial state, is hybridity, a

contingent, borderline experience [that] opens up in-between colonizer and

colonized (Bhabha, Location 206). As Rio Gonzagaone of the two

central narrators in the noveland, through her, Hagedorn, look back and

attempt to reconstruct themselves and their nation, the book itself

embodies a postcolonial quest and enacts what Timothy Brennan refers to

as a national yearning for form (44) that would be inclusive of the

broken fragments of different identity formations. Senator Avila,

portrayed as a major political player in the novel, expresses the crisis

endemic to postcolonial self-definitions. According to him, the Filipinos

are a complex nation of cynics, descendants of warring tribes which were

baptized and colonized to death by Spaniards and Americans, . . . a nation

betrayed and then united only by our hunger for glamour and our

Hollywood dreams (101). San Juans remarks are to the point:

By grace of over 400 years of colonial and neocolonial domination, the inhabitants of the

islands called the Philippines have acquired an identity, a society and a culture, not

totally of their own making. We share this fate with millions of other third world

peoples. We Filipino(a)s have been constructed by Others (Spaniards, Japanese, the

Amerikanos) . . . . (6)

The blurring of Filipino and American identities in the nation, as Rachel

Lee points out, has a genealogical corollary in the ancestral backgrounds

of the novels first person narrators, Rio Gonzaga and Joey Sands (75).

Rios narration dwells on the colonial remnants embedded in her

family roots. Her father believes in dual citizenships, dual passports, as

many allegiances to as many countries as possible at any one given time

(7) and considers himself a guest in the Philippines, though, as his wife

points out, his family has lived here for generationsa mestizo, but a

Filipino (8). In contrast, Rios Rita Hayworth mother, who carries

American papers because of her father, feels more viscerally connected

to the Philippines (8). Pucha Gonzaga, Rios cousin, idolizes Hollywood

stars. Puchas elder brothers dream is to see Elizabeth Taylor naked

(15). The exile-native-narrator, Rio herself, traces her family roots through

Hollywood iconography, reimagining and reconstructing her genealogy

(16). Lola Narcisa, Rios Asian grandmother, is allied to America by her

9

Postcolonial Text Vol 5 No 2 (2009)

marriage to a Midwest American. Thus the postcolonial residue in the

Filipino psyche, as Lee observes, renders questions of purity and

authenticity unresolvable (167).

Rios grandfather moaning for Chicago on his deathbed in an

American hospital in Manila (16) draws attention as much to his American

origins as to the general American presence on Filipino soil. Suffering

from bangungot, he acquires the dubious honor of being the first white

man to be afflicted by this native ailment, though the American doctor

dismisses the tropical melody as native superstition, a figment of the

overwrought Filipino imagination (14). His wife, Lola Narcisa, Rios

gray-eyed grandmother, is brown-skinned (7) and their marriage, at

one level, symbolizes the uneasy and complex alliance of the east and

west wrought by colonization. Lola Narcisa is, as Rio depicts her, a

colonized subject in her own home. Described as invisible, and as

some tiny woman who happens to be visiting (9), she lives in a guest

room next to the kitchen (9) and eats with the servants. In this

postcolonial family, the dark-skinned, native-identified grandmother is

not asked to sit at our dinner table (9). Listening to the radio show Love

Letters with her servants, Narcisa becomes part of the lowest common

denominator (11). In this familial reproduction of postcolonial politics,

Hagedorn shows the neocolonial tendencies in an upper-class family in the

Philippines. Rios psychic alliance with her grandmother and the

appreciation for Love Letters that she shares with her ancestor mark her

out to be one of the bakya [low] crowd (11), and Rios present life in

America could, perhaps, define her as an elitist, colonial agent/mimic. Rio

herself is a confused postcolonial product and this schizophrenic cultural

response (De Jesus 226) is Hagedorns center.

The layered nature of postcolonial Philippine identity, glimpsed in

Rio, is exemplified most tellingly in the roots of the novels other narrator,

Joey Sands. The son of a Black American military man stationed in the

Philippines and born to a legendary whore (42), Joey emblematizes the

fluidity and instability of the Philippine national identity itself. The fact

that he is gay further emphasizes this instability, and through his parentage

the military presence of a colonial power is brought surreptitiously into the

novel, validating the claim that the textual submergence of the militias

presence mimics the subdued infiltration of the islands by an American

neocolonial presence (Lee 76).

If Rio and Joey are fictional characters embodying the nature of

postcolonial identity, historical characters are fictionalized to show the

impact of colonization on a nation trying to build itself. In a telling

narration, Hagedorn blurs history and fiction by making Joey witness a

historic event: the assassination of opposition leader Senator Avila, standin for Benigno Aquino who was killed on August 21, 1983. The personal

sagas of the characters tumbling into Philippine history enact the

transfusion of histories into the body of the fictional narrative,

mongrelizing, molding, and misshaping it. Joey plays a crucial role in

Hagedorns defiance of generic adherence, a defiance that undercuts

10

Postcolonial Text Vol 5 No 2 (2009)

hegemonic-dualistic paradigms and aligns the writers postcolonial

politics with postmodern aesthetics; as Linda Hutcheon notes, a primary

feature of the postmodern novel is that the borders between literary

genres . . . become fluid (250). Refusing to settle into generic stability,

the text staggers in the slippery zones of historiographic metafiction

(Hutcheon 245). The melding fiction and history contests univocalist

pretences to truth by showing that it is not always the nature of history to

be true and that of fiction to be false. Hagedorns mixing of historical facts

with imaginary events not only transgresses generic boundaries that

demarcate history and its connotative privilege of truth from fiction, but

also challenges the assumption of factuality that underlies canonical

histories, including nationalist discourses. Joey Sands, the gay narrator in

the tale, is a strategically significant tool in Hagedorns transgressive art.

Sexual and State politics are intimately entangled in Jessica Hagedorns

Dogeaters (1990) not only in the maintenance of state, nationalist and

neocolonial systems of power but also and especially in their transgression

or perversion, observes Victor Mendoza (815) and Joey, the queer

subject who subverts, eludes, and evades authority, the possessor of an

important state secret, and the fugitive who refuses to yield, makes a

mockery of state power.

The fact that violence is a feature of postcolonial Philippines, as it

was in many nations recuperating after colonization, is made explicit in

Senator Avilas assassination. Dogeaters mixes history and fiction, and

presents Aquino/Avilas assassination, symptom of a nations malaise,

through the eyes of a marginalized, unrecognized citizen-historian,

fictional Joey Sands. By making Joey, the outsider (an outsider by class,

race, profession and sexual preference), witness and narrate the political

leaders death, and by linking his survival to a historic event on whose

outcome a postcolonial nations destiny is tied, Hagedorn coalesces the

personal fate of individuals and the larger destiny of a nation, both beset

by deadly threats to their existence. Simply to stay alive, as country and as

individual, is a challenge now. Joey Sands is thus a representative not only

of the plural, scattered, mongrel, unstable psyche of a postcolonial people,

but also of a nation coming to grips with the violence unleashed after

years of foreign occupation.

Hagedorn does not portray postcolonial, plural Philippines as a

monolith, nor glorify its plurality. There is no calm after the storm here.

The nation is revealed with its fissures and wounds gaping. As Hagedorn

observes elsewhere, What is literature for? . . . You dont go to literature

and say I need to feel good about my race, so let me read a novel (qtd. in

Lee 167). However, the texts major story lines, most of which relate to

women, churn out a critique of purity and homogeneity, generously

embracing the impure, the perverse, and the off beat in a spirit of historic

generosity.

In Dogeaters, Hagedorn as a postcolonial writer sets out to explore

the problems of identity for a nation and its inhabitants, especially its

marginalized inhabitants. This political-aesthetic task is complicated by

11

Postcolonial Text Vol 5 No 2 (2009)

the fact that she lives in America and writes in English and also by the

hybrid character of her native nation in which Americanness and

colonizing attitudes the text is too complex to make one a synonym for

the other have come to stay. What she reclaims of and for her nation and

its people are, perhaps, only imagined fragments of a broken nation.

Rushdies remark that postcolonial writers in exile will not be capable of

reclaiming precisely the thing that was lost; that we [postcolonial,

expatriate writers] will, in short, create fictions, not actual cities or

villages, but invisible ones, imaginary homelands . . . of the mind (10)

captures the spirit of Hagedorns endeavor. The fragmented, dream-like

narration of Dogeaters portrays the psychic landscape of a conquered

land, staggering under nationalism and surviving the weight of a colonial

past. Dealing with what Rushdie calls broken mirrors, some of whose

fragments have been irretrievably lost (10-11), Hagedorn dramatizes the

fragmentation of a postcolonial society in a diasporic narrative that

exposes the horrors of colonialism and neocolonial nationalism as

constituting one long, hegemonic continuum.

Works Cited

Ashcroft, Bill, Gareth Griffiths, and Helen Tiffin. The Empire Writes

Back: Theory and Practice in Post-Colonial Literatures. London:

Routledge, 1989.

Bhabha, Homi K. The Location of Culture. London: Routledge, 1994.

. The Third Space: Interview with Homi K. Bhabha. Identity:

Community, Culture, Difference. Ed. Jonathan Rutherford. London:

Lawrence, 1990. 207-21.

Boehmer, Elleke. Colonial and Postcolonial Literature: Migrant

Metaphors. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1995.

Brennan, Timothy. The National Longing for Form. Nation and

Narration. Ed. Homi K. Bhabha. London: Routledge, 1990. 44-70.

Brownmiller, Susan. Against Our Will: Men, Women, and Rape. New

York: Simon, 1975.

Chang, Juliana. Masquerade, Hysteria and Neocolonial Femininity in

Jessica Hagedorns Dogeaters. Contemporary Literature 44.4

(2003): 637-63.

DAlpuget, Blanche. Philippine Dreamfest. Rev. of Dogeaters by

Jessica Hagedorn. New York Times Book Review 25 Mar. 1990: 1+.

De Jesus, Melinda L. Liminality and Mestiza Consciousness in Lynda

Barrys One Hundred Demons. Filipino American Literature. Spec.

issue of MELUS 29.1 (2004): 219-52.

Grice, Helena. Artistic Creativity, Form, and Fictional Experimentation

in Filipina American Fiction. Filipino American Literature. Spec.

issue of MELUS 29.1 (2004): 181-88.

Hagedorn, Jessica. Dogeaters. New York: Penguin, 1990.

. Interview with Kay Bonetti. Missouri Review 18.1 (1995). 3 Mar.

2010

12

Postcolonial Text Vol 5 No 2 (2009)

<http://moreview.com/content/dynamic/view_text.php?text_id=1945

>

. Introduction. Danger and Beauty. New York: Penguin, 1993. ix-xi.

Hanisch, Carol. The Personal Is Political: The Womens Liberation

Movement Classic with a New Explanatory Introduction. Women of

the World, Unite! Writings by Carol Hanisch. Jan. 2006. 9 Mar. 2010

<http://carolhanisch.org/CHwritings/PIP.html>

Hutcheon, Linda. Beginning to Theorize Postmodernism. A Postmodern

Reader. Ed. Joseph Natoli and Linda Hutcheon. Albany: State U of

New York P, 1993. 243-72.

Kaplan, Ann. Looking for the Other: Feminism, Film, and the Imperial

Gaze. London: Routledge, 1997.

Lee, Rachel. Transversing Nationalism, Gender, and Sexuality in Jessica

Hagedorns Dogeaters. The Americas of Asian American Literature:

Gendered Fictions of Nation and Transnation. Princeton: Princeton

UP, 1999. 73-105.

Loomba, Ania. Colonialism/Postcolonialism. New Critical Idiom.

London: Routledge, 1998.

Lowe, Lisa. Immigrant Acts: On Asian American Cultural Politics.

Durham: Duke UP, 1996.

Mendible, Myra. Dictators, Movie Stars, and Martyrs: The Politics of

Spectacle in Jessica Hagedorns Dogeaters. Genders 36 (2002). 3

Mar. 2010 <http://www.genders.org/g36/g36_mendible.html>.

Mendoza, Victor. A Queer Nomadology of Jessica Hagedorns

Dogeaters. American Literature 77.4 (2005): 815-45.

Minh-Ha, Trinh T. Woman Native Other: Writing Postcoloniality and

Feminism. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1989.

Nubla, Gladys. The Politics of Relation: Creole Languages in Dogeaters

and Rolling the Rs. Filipino American Literature. Spec. issue of

MELUS 29.1 (2004): 199-218.

Rushdie, Salman. Imaginary Homelands. London: Granta, 1991.

Said, Edward. Orientalism. New York: Vintage, 1979.

San Juan, E., Jr. Transforming Identity in Postcolonial Narrative: An

Approach to the Novels of Jessica Hagedorn. Post Identity 1.2

(1998): 5-28. 3 Mar. 2010

<http://liberalarts.udmercy.edu/pi/PI1.2/PI12_Juan.pdf>.

See, Sarita. Southern Postcoloniality and the Improbability of Filipino

American Postcoloniality: Faulkners Absalom, Absalom! and

Hagedorns Dogeaters. The U.S. South, Postcolonial Theory, and

New World Studies. Spec. issue of Mississippi Quarterly 57.1 (20032004): 41-54.

Spacks, Patricia Meyer. Gossip. New York: Knopf, 1985.

Spivak, Gayatri. Can the Subaltern Speak? The Norton Anthology of

Theory and Criticism. Ed. Vincent B. Leitch et al. New York: Norton,

2001. 2197-208.

Sulit, Marie-Therese. The Philippine Diaspora, Hunger and ReImagining Community: An Overview of Works by Filipina and

13

Postcolonial Text Vol 5 No 2 (2009)

Filipina American Writers. Transnational, National, and Personal

Voices: New Perspectives on Asian American and Asian Diasporic

Women Writers. Ed. Begona Simal and Elisabetta Marino. Berlin:

LIT, 2004. 119-50.

Viswanathan, Gauri. Masks of Conquest: Literary Studies and British Rule

in India. London: Faber, 1989.

14

Postcolonial Text Vol 5 No 2 (2009)

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Reading The Color Purple From The Perspective of EcofeminismDocumento8 pagineReading The Color Purple From The Perspective of EcofeminismMalik TahirNessuna valutazione finora

- Subversive Spirits: The Female Ghost in British and American Popular CultureDa EverandSubversive Spirits: The Female Ghost in British and American Popular CultureValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (2)

- Filipina's Image in 20th Century Philippine LiteratureDocumento14 pagineFilipina's Image in 20th Century Philippine Literaturelouie21100% (1)

- Our Living Manhood: Literature, Black Power, and Masculine IdeologyDa EverandOur Living Manhood: Literature, Black Power, and Masculine IdeologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Sexuality and War: Literary Masks of the Middle EastDa EverandSexuality and War: Literary Masks of the Middle EastNessuna valutazione finora

- Resistance Against Marginalization of Afro-American Women in Alice Walker's The Color PurpleDocumento9 pagineResistance Against Marginalization of Afro-American Women in Alice Walker's The Color PurpleIJELS Research JournalNessuna valutazione finora

- Reasserting Female Subjectivity in RichDocumento11 pagineReasserting Female Subjectivity in Richpradip sharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Tableaux Vivants: Female Identity Development Through Everyday PerformanceDa EverandTableaux Vivants: Female Identity Development Through Everyday PerformanceNessuna valutazione finora

- 2 Ijeloct20172Documento10 pagine2 Ijeloct20172TJPRC PublicationsNessuna valutazione finora

- For Antifascist Futures: Against the Violence of Imperial CrisisDa EverandFor Antifascist Futures: Against the Violence of Imperial CrisisNessuna valutazione finora

- Feminist Critics and Their TheoriesDocumento7 pagineFeminist Critics and Their TheoriesMANJUNATH BHEEMANNAVARNessuna valutazione finora

- Decolonizing Feminisms: Race, Gender, and Empire-buildingDa EverandDecolonizing Feminisms: Race, Gender, and Empire-buildingValutazione: 3 su 5 stelle3/5 (1)

- Redefining Space in Eva LunaDocumento4 pagineRedefining Space in Eva LunaIJELS Research JournalNessuna valutazione finora

- Gendered Identities in Post-Colonial Literature of AustraliaDocumento5 pagineGendered Identities in Post-Colonial Literature of AustraliaShivani BhayNessuna valutazione finora

- Tragic Dimensions of PecolaDocumento13 pagineTragic Dimensions of PecolaNukhba ZainNessuna valutazione finora

- Summary - AutobiographyDocumento7 pagineSummary - AutobiographyIrbab YounisNessuna valutazione finora

- Draupadi As A Subaltern TextDocumento6 pagineDraupadi As A Subaltern TextDaffodil50% (2)

- From Bourgeois to Boojie: Black Middle-Class PerformancesDa EverandFrom Bourgeois to Boojie: Black Middle-Class PerformancesNessuna valutazione finora

- Mahasweta Devi's "DraupadiDocumento9 pagineMahasweta Devi's "DraupadiRobin SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- Gothic and Racism, 2nd edition, revised and enlargedDa EverandGothic and Racism, 2nd edition, revised and enlargedNessuna valutazione finora

- Feminine Search For Identity in Shauna Singh Baldwin's Novel What The Body RemembersDocumento4 pagineFeminine Search For Identity in Shauna Singh Baldwin's Novel What The Body RemembersIJELS Research Journal100% (1)

- Dismantling Gendered NationalismDocumento14 pagineDismantling Gendered NationalismZachary FaroukNessuna valutazione finora

- Bodily Evidence: Racism, Slavery, and Maternal Power in the Novels of Toni MorrisonDa EverandBodily Evidence: Racism, Slavery, and Maternal Power in the Novels of Toni MorrisonValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- HumanitiesDocumento15 pagineHumanitiesYounes SncNessuna valutazione finora

- Homosocial Bonding and The Oppression of Women in "My Son The Fanatic," by Hanif KureishiDocumento14 pagineHomosocial Bonding and The Oppression of Women in "My Son The Fanatic," by Hanif KureishiNatalia BarreraNessuna valutazione finora

- Hypermasculinity. The Exaggeration of Male Stereotypical Behavior Through The Figure of The DictatorDocumento5 pagineHypermasculinity. The Exaggeration of Male Stereotypical Behavior Through The Figure of The Dictatorsofía lobos moralesNessuna valutazione finora

- Feminist Postcolonial BelovedDocumento17 pagineFeminist Postcolonial BelovedBeaNessuna valutazione finora

- Marxist Reading of Selected African Drama Texts by Tobi IdowuDocumento5 pagineMarxist Reading of Selected African Drama Texts by Tobi IdowuAmb SesayNessuna valutazione finora

- Erotic Autonomy As A Politics of DecolonizationDocumento25 pagineErotic Autonomy As A Politics of DecolonizationJon Natan100% (2)

- Allan Ai Term Porject Draft Step 3Documento9 pagineAllan Ai Term Porject Draft Step 3api-642835707Nessuna valutazione finora

- (251 5) RPTitusAndronicusDocumento3 pagine(251 5) RPTitusAndronicusNachtFuehrerNessuna valutazione finora

- ArmeenAhuja AyushiJain 1064 PoCoLitDocumento7 pagineArmeenAhuja AyushiJain 1064 PoCoLitpankhuriNessuna valutazione finora

- "All That You Touch You Change": Utopian Desire and the Concept of Change in Octavia Butler's Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents by Patricia Melzer, Femspec Issue 3.2Da Everand"All That You Touch You Change": Utopian Desire and the Concept of Change in Octavia Butler's Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents by Patricia Melzer, Femspec Issue 3.2Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Bluest Eye ReferenceDocumento14 pagineThe Bluest Eye ReferenceSensai KamakshiNessuna valutazione finora

- Jacobean Revenge TragedyDocumento5 pagineJacobean Revenge TragedynarkotiaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Everyday Life of The Revolution: Gender, Violence and Memory Srila RoyDocumento21 pagineThe Everyday Life of The Revolution: Gender, Violence and Memory Srila Roypallavimagic1Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Majority Finds Its Past: Placing Women in HistoryDa EverandThe Majority Finds Its Past: Placing Women in HistoryValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (2)

- Adrienne Davis Don't Let Nobody Bother Yo' PrincipleDocumento12 pagineAdrienne Davis Don't Let Nobody Bother Yo' PrinciplegonzaloluyoNessuna valutazione finora

- An Insight into the Horrors of Partition, Colonialism and Women's Issues: "A Saga of Oppression, Exploitation and Conflict"Da EverandAn Insight into the Horrors of Partition, Colonialism and Women's Issues: "A Saga of Oppression, Exploitation and Conflict"Nessuna valutazione finora

- A Room of One S One Coco FuscoDocumento5 pagineA Room of One S One Coco FuscoMonica Eraso JuradoNessuna valutazione finora

- Group 6 - Critical PaperDocumento30 pagineGroup 6 - Critical PaperTISJA DELA CRUZNessuna valutazione finora

- Imposing Fictions: Subversive Literature and the Imperative of AuthenticityDa EverandImposing Fictions: Subversive Literature and the Imperative of AuthenticityNessuna valutazione finora

- 1500 Words-HerosDocumento7 pagine1500 Words-Herosibrahim shahNessuna valutazione finora

- Feminism and Literary RepresentationDocumento11 pagineFeminism and Literary RepresentationMoh FathoniNessuna valutazione finora

- Funkthe Erotic 7Documento27 pagineFunkthe Erotic 7reynoldscjNessuna valutazione finora

- Frankenstein Presentation FinalDocumento8 pagineFrankenstein Presentation FinalHarshika AroraNessuna valutazione finora

- Confronting Cultural Stereotypes MotherhDocumento11 pagineConfronting Cultural Stereotypes Motherhanaiel nymviaNessuna valutazione finora

- Handmaid's Tale Female IdentityDocumento10 pagineHandmaid's Tale Female Identityamira100% (2)

- Womanism and The Color Purple: Long ShiDocumento4 pagineWomanism and The Color Purple: Long ShiAkanu JoyNessuna valutazione finora

- Almirath BookDocumento88 pagineAlmirath Bookmosabbeh100% (1)

- 2062-Article Text-7390-1-10-20190123Documento10 pagine2062-Article Text-7390-1-10-20190123UsmanNessuna valutazione finora

- Patterns of Reticence and Counter Affirmation in Isabel Allende's The House of The SpiritsDocumento4 paginePatterns of Reticence and Counter Affirmation in Isabel Allende's The House of The SpiritsLayan AljandanNessuna valutazione finora

- FeminismDocumento37 pagineFeminismEmmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Muñoz and Fusco - A Room of One's Own - Women and Power in The New AmericaDocumento4 pagineMuñoz and Fusco - A Room of One's Own - Women and Power in The New AmericaMariana OlivaresNessuna valutazione finora

- Understanding Blackness through Performance: Contemporary Arts and the Representation of IdentityDa EverandUnderstanding Blackness through Performance: Contemporary Arts and the Representation of IdentityNessuna valutazione finora

- Psychoanalysis & a Historical Story of Ghenghis KhanDa EverandPsychoanalysis & a Historical Story of Ghenghis KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- 1762-Article Text-4659-1-18-20221006Documento16 pagine1762-Article Text-4659-1-18-20221006Alejandro Batista TejadaNessuna valutazione finora

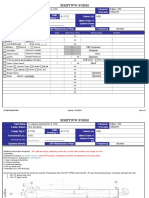

- 2014 Bir Rr9 Tax Quiz BeeDocumento1 pagina2014 Bir Rr9 Tax Quiz BeesuperultimateamazingNessuna valutazione finora

- SONA Reaction Paper GuideDocumento2 pagineSONA Reaction Paper GuidesuperultimateamazingNessuna valutazione finora

- ChemistryDocumento15 pagineChemistrysuperultimateamazingNessuna valutazione finora

- Financial Accounting Theory Test Bank QuestionsDocumento11 pagineFinancial Accounting Theory Test Bank QuestionsJimmyChaoNessuna valutazione finora

- ChemistryDocumento2 pagineChemistrysuperultimateamazingNessuna valutazione finora

- Supplier's Name The Perfect White Shirt The Ermano Prints and Apparel Method of Printing Type of Shirt QuotationsDocumento1 paginaSupplier's Name The Perfect White Shirt The Ermano Prints and Apparel Method of Printing Type of Shirt QuotationssuperultimateamazingNessuna valutazione finora

- Ap-5905 Inventories PDFDocumento9 pagineAp-5905 Inventories PDFKathleen Jane SolmayorNessuna valutazione finora

- 2014 Quiz Edited Elimination BIRDocumento12 pagine2014 Quiz Edited Elimination BIRBlairEmrallafNessuna valutazione finora

- Ap Receivables Quizzer507Documento20 pagineAp Receivables Quizzer507Jean Tan100% (1)

- Royal SelfierDocumento2 pagineRoyal SelfiersuperultimateamazingNessuna valutazione finora

- Ap-5905 Inventories PDFDocumento9 pagineAp-5905 Inventories PDFKathleen Jane SolmayorNessuna valutazione finora

- Nca - MCDocumento1 paginaNca - MCsuperultimateamazingNessuna valutazione finora

- Ap-5905 Inventories PDFDocumento9 pagineAp-5905 Inventories PDFKathleen Jane SolmayorNessuna valutazione finora

- CH 04Documento6 pagineCH 04Joffrey UrianNessuna valutazione finora

- Pre-Spanish and Spanish Colonial EraDocumento8 paginePre-Spanish and Spanish Colonial ErasuperultimateamazingNessuna valutazione finora

- Funnel Test Tube Holder Test Tube Rack Test Tube Brush Crucible Crucible TongsDocumento8 pagineFunnel Test Tube Holder Test Tube Rack Test Tube Brush Crucible Crucible TongssuperultimateamazingNessuna valutazione finora

- BSPDocumento9 pagineBSPsuperultimateamazingNessuna valutazione finora

- Philippine Eagle-Owl : Bubo PhilippensisDocumento3 paginePhilippine Eagle-Owl : Bubo PhilippensissuperultimateamazingNessuna valutazione finora

- LyricsDocumento6 pagineLyricssuperultimateamazingNessuna valutazione finora

- TAX RATES AND CLASSIFICATIONS FOR CORPORATE AND INDIVIDUAL TAXPAYERSDocumento4 pagineTAX RATES AND CLASSIFICATIONS FOR CORPORATE AND INDIVIDUAL TAXPAYERSsuperultimateamazingNessuna valutazione finora

- Management AccountingDocumento29 pagineManagement AccountingsuperultimateamazingNessuna valutazione finora

- Episode 3 - : July 8 - July 14 - P. 2 - p.3 - July 10 - July 22Documento2 pagineEpisode 3 - : July 8 - July 14 - P. 2 - p.3 - July 10 - July 22superultimateamazingNessuna valutazione finora

- BankingDocumento4 pagineBankingsuperultimateamazingNessuna valutazione finora

- Speech Philippine LiteratureDocumento5 pagineSpeech Philippine LiteraturesuperultimateamazingNessuna valutazione finora

- Filipino Consumers Remain Price-Sensitive Despite Economic GrowthDocumento6 pagineFilipino Consumers Remain Price-Sensitive Despite Economic GrowthsuperultimateamazingNessuna valutazione finora

- Concepts of AccountingDocumento2 pagineConcepts of AccountingsuperultimateamazingNessuna valutazione finora

- Pol AnalysisDocumento2 paginePol AnalysissuperultimateamazingNessuna valutazione finora

- Pol RegDocumento1 paginaPol RegsuperultimateamazingNessuna valutazione finora

- Sources:: 134 - Regulation (Standards of Identity and Quality of Vinegar) PDFDocumento1 paginaSources:: 134 - Regulation (Standards of Identity and Quality of Vinegar) PDFsuperultimateamazingNessuna valutazione finora

- Pol RegDocumento2 paginePol RegsuperultimateamazingNessuna valutazione finora

- Team Roles EssayDocumento7 pagineTeam Roles EssayCecilie Elisabeth KristensenNessuna valutazione finora

- 2-Library - IJLSR - Information - SumanDocumento10 pagine2-Library - IJLSR - Information - SumanTJPRC PublicationsNessuna valutazione finora

- Volvo FM/FH with Volvo Compact Retarder VR 3250 Technical DataDocumento2 pagineVolvo FM/FH with Volvo Compact Retarder VR 3250 Technical Dataaquilescachoyo50% (2)

- RFID Sticker and and Card Replacement 2019 PDFDocumento1 paginaRFID Sticker and and Card Replacement 2019 PDFJessamyn DimalibotNessuna valutazione finora

- MAS-06 WORKING CAPITAL OPTIMIZATIONDocumento9 pagineMAS-06 WORKING CAPITAL OPTIMIZATIONEinstein Salcedo100% (1)

- Frendx: Mara IDocumento56 pagineFrendx: Mara IKasi XswlNessuna valutazione finora

- Felomino Urbano vs. IAC, G.R. No. 72964, January 7, 1988 ( (157 SCRA 7)Documento1 paginaFelomino Urbano vs. IAC, G.R. No. 72964, January 7, 1988 ( (157 SCRA 7)Dwight LoNessuna valutazione finora

- Common Application FormDocumento5 pagineCommon Application FormKiranchand SamantarayNessuna valutazione finora

- Batman Vs Riddler RiddlesDocumento3 pagineBatman Vs Riddler RiddlesRoy Lustre AgbonNessuna valutazione finora

- BMW E9x Code ListDocumento2 pagineBMW E9x Code ListTomasz FlisNessuna valutazione finora

- Simptww S-1105Documento3 pagineSimptww S-1105Vijay RajaindranNessuna valutazione finora

- DODAR Analyse DiagramDocumento2 pagineDODAR Analyse DiagramDavidNessuna valutazione finora

- Opportunity Seeking, Screening, and SeizingDocumento24 pagineOpportunity Seeking, Screening, and SeizingHLeigh Nietes-GabutanNessuna valutazione finora

- Multidimensional ScalingDocumento25 pagineMultidimensional ScalingRinkiNessuna valutazione finora

- Helen Hodgson - Couple's Massage Handbook Deepen Your Relationship With The Healing Power of TouchDocumento268 pagineHelen Hodgson - Couple's Massage Handbook Deepen Your Relationship With The Healing Power of TouchLuca DatoNessuna valutazione finora

- The Best Chess BooksDocumento3 pagineThe Best Chess BooksJames Warren100% (1)

- Full Download Ebook Ebook PDF Nanomaterials Based Coatings Fundamentals and Applications PDFDocumento51 pagineFull Download Ebook Ebook PDF Nanomaterials Based Coatings Fundamentals and Applications PDFcarolyn.hutchins983100% (43)

- Pembaruan Hukum Melalui Lembaga PraperadilanDocumento20 paginePembaruan Hukum Melalui Lembaga PraperadilanBebekliarNessuna valutazione finora

- Other Project Content-1 To 8Documento8 pagineOther Project Content-1 To 8Amit PasiNessuna valutazione finora

- Evaluation of Evidence-Based Practices in Online Learning: A Meta-Analysis and Review of Online Learning StudiesDocumento93 pagineEvaluation of Evidence-Based Practices in Online Learning: A Meta-Analysis and Review of Online Learning Studiesmario100% (3)

- INDEX OF 3D PRINTED CONCRETE RESEARCH DOCUMENTDocumento15 pagineINDEX OF 3D PRINTED CONCRETE RESEARCH DOCUMENTAkhwari W. PamungkasjatiNessuna valutazione finora

- AReviewof Environmental Impactof Azo Dyes International PublicationDocumento18 pagineAReviewof Environmental Impactof Azo Dyes International PublicationPvd CoatingNessuna valutazione finora

- Sustainable Marketing and Consumers Preferences in Tourism 2167Documento5 pagineSustainable Marketing and Consumers Preferences in Tourism 2167DanielNessuna valutazione finora

- Diabetic Foot InfectionDocumento26 pagineDiabetic Foot InfectionAmanda Abdat100% (1)

- Cell Types: Plant and Animal TissuesDocumento40 pagineCell Types: Plant and Animal TissuesMARY ANN PANGANNessuna valutazione finora

- Form 16 PDFDocumento3 pagineForm 16 PDFkk_mishaNessuna valutazione finora

- PRI Vs SIP Trunking WPDocumento3 paginePRI Vs SIP Trunking WPhisham_abdelaleemNessuna valutazione finora

- Mr. Bill: Phone: 086 - 050 - 0379Documento23 pagineMr. Bill: Phone: 086 - 050 - 0379teachererika_sjcNessuna valutazione finora

- De Minimis and Fringe BenefitsDocumento14 pagineDe Minimis and Fringe BenefitsCza PeñaNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 9Documento3 pagineUnit 9Janna Rick100% (1)