Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Unesco - Eolss Sample Chapters: The Economics of Bargaining

Caricato da

mnaka19837343Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Unesco - Eolss Sample Chapters: The Economics of Bargaining

Caricato da

mnaka19837343Copyright:

Formati disponibili

FUNDAMENTAL ECONOMICS Vol.

I - The Economics of Bargaining - Abhinay Muthoo

THE ECONOMICS OF BARGAINING

Abhinay Muthoo

University of Essex, UK

Keywords : bargaining, nash bargaining, Rubinstein model, breakdown risk, outside

options, inside options, asymmetric information, repeated bargaining situations.

Contents

U

SA N

M ES

PL C

E O

C E

H O

AP L

TE SS

R

S

1. Introduction

2. Bargaining Situations and Bargaining

2.1.An Outline of this Article

3. The Nash Bargaining Solution

3.1.An Application to Bribery and the Control of Crime

3.2.Asymmetric Nash Bargaining Solutions

4. The Rubinstein Model

4.1.The Alternating-Offers Model

4.2.The Unique Subgame Perfect Equilibrium

4.3.Properties of the Equilibrium

4.3.1 Relationship with Nashs Bargaining Solution

4.3.2 The Value and Interpretation of the Alternating-Offers Model

5. Risk of Breakdown

6. Outside Options

7. Inside Options

7.1.An Application to Sovereign Debt Renegotiations

8. Asymmetric Information

8.1.The Case of Private Values

8.2.The Case of Correlated Values

9. Repeated Bargaining Situations

9.1.The Unique Stationary Subgame Perfect Equilibrium

9.2.Small Time Intervals Between Consecutive OffersConcluding Remarks

Acknowledgements

Bibliography

Biographical Sketch

Summary

This article presents the main principles of bargaining theory, along with some

examples to illustrate the potential applicability of this theory to a variety of real-life

bargaining situations. It will be shown that such models can be adapted, extended, and

modified in order to explore other issues concerning bargaining situations.

1. Introduction

Bargaining is ubiquitous. Married couples negotiate over a variety of matters such as

who will do which domestic chores. Government policy is typically the outcome of

negotiations amongst cabinet ministers. Whether or not a particular piece of legislation

Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS)

FUNDAMENTAL ECONOMICS Vol. I - The Economics of Bargaining - Abhinay Muthoo

meets with the legislatures approval may depend on the outcome of negotiations

amongst the dominant political parties. National governments are often engaged in a

variety of international negotiations on matters ranging from economic issues (such as

the removal of trade restrictions) to global security (such as the reduction in the

stockpiles of conventional armaments, and nuclear nonproliferation and test bans) and

environmental and related issues (such as carbon emissions trading, biodiversity

conservation, and intellectual property rights). Much economic interaction involves

negotiations on a variety of issues. Wages and prices of other commodities (such as oil,

gas, and computer chips) are often the outcome of negotiations amongst the concerned

parties. Mergers and acquisitions require negotiations over, amongst other issues, the

price at which such transactions are to take place.

U

SA N

M ES

PL C

E O

C E

H O

AP L

TE SS

R

S

What variables (or factors) determine the outcome of negotiations such as those

mentioned above? What are the sources of bargaining power? What strategies can help

improve ones bargaining power? What variables determine whether parties to a

territorial dispute will reach a negotiated settlement, or engage in military war? How

can one enhance the likelihood that parties in such negotiations will strike an agreement

quickly to minimize the loss of life through war? What strategies should one adopt to

maximize the negotiated sale price of ones house? How can one negotiate a better deal

(such as a wage increase) from ones employers?

Bargaining theory seeks to address the above and many similar real-life questions

concerning bargaining situations.

2. Bargaining Situations and Bargaining

Consider the following situation. An individual, called Aruna, owns a house that she is

willing to sell at a minimum price of 50 000; that is, she values her house at

50 000. Another individual, called Mohan, is willing to pay up to 70 000 for Arunas

house; that is, he values her house at 70 000. If trade occursthat is, if Aruna sells the

house to Mohanat a price that lies between 50 000 and 70 000, then both Aruna

(the seller) and Mohan (the buyer) would become better off. This means that, in this

situation, these two individuals have a common interest to trade. At the same time,

however, they have conflicting (or divergent) interests over the price at which to trade:

Aruna, the seller, would like to trade at a high price, while Mohan, the buyer, would like

to trade at a low price.

Any exchange situation, such as the one just described, in which a pair of individuals

(or organizations) can engage in mutually beneficial trade but have conflicting interests

over terms of trade is a bargaining situation. Stated in general terms, a bargaining

situation is a situation in which two or more players have a common interest to

cooperate, but have conflicting interests over exactly how to cooperate. (A player can

be either an individual or an organization (such as a firm, a political party, or a

country).)

There are two main reasons for being interested in bargaining situations. The first,

practical reason is that many important and interesting human (economic, social, and

political) interactions are bargaining situations. As mentioned above, exchange

Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS)

FUNDAMENTAL ECONOMICS Vol. I - The Economics of Bargaining - Abhinay Muthoo

situations (which characterize much of human economic interaction) are bargaining

situations. In the arena of social interaction, a married couple, for example, is involved

in many bargaining situations throughout the relationship. In the political arena, a

bargaining situation exists, for example, when no single political party on its own can

form a government (such as when there is a hung parliament): the party that has

obtained the most votes will typically find itself in a bargaining situation with one or

more of the other parties. The second, theoretical reason for being interested in

bargaining situations is that understanding such situations is fundamental to

understanding the workings of markets and the appropriateness, or otherwise, of

prevailing monetary and fiscal policies.

U

SA N

M ES

PL C

E O

C E

H O

AP L

TE SS

R

S

The main issue that confronts the players in a bargaining situation is the need to reach

agreement over exactly how to cooperate. Each player would like to reach some

agreement, rather than disagree and not reach any agreement, but each player would

also like to reach an agreement that is as favorable to that individual as possible. It is

thus feasible that the players will strike an agreement only after some costly delay, or

indeed fail to reach an agreementas is witnessed by the history of disagreements and

costly delayed agreements in many real-life situations (as exemplified by the

occurrences of trade wars, military wars, strikes, and divorce).

Bargaining is any process through which the players try to reach an agreement. This

process is typically time consuming, and involves the players making offers and

counteroffers to each other. Any theory of bargaining focuses on the efficiency and

distribution properties of the outcome of bargaining. The former property relates to the

possibility that the players fail to reach an agreement, or that they reach an agreement

after some costly delay. Examples of costly delayed agreements include when a wage

agreement is reached after lost production due to a long strike, and when a peace

settlement is negotiated after the loss of life through war. The distribution property

relates to the issue of exactly how the gains from cooperation are divided between the

players.

The principles of bargaining theory set out in this article determine the roles of various

key factors (or variables) on the bargaining outcome (and its efficiency and distribution

properties). As such, they determine the sources of a players bargaining power.

2.1 An Outline of this Article

If the bargaining process is frictionlessby which we mean that neither player incurs

any cost from hagglingthen each player may continuously demand that agreement be

struck on terms that are most favorable to that player. (For example, in the exchange

situation described above, Aruna may continuously demand that trade take place at the

price of 69 000, while Mohan may continuously demand that it take place at 51 000.)

In such circumstances, the negotiations are likely to end up in an impasse (or deadlock),

since the negotiators would have no incentive to compromise and reach an agreement.

Indeed, if it did not matter when the negotiators agree, then it would not matter whether

they agreed at all. In most real-life situations, the bargaining process is not frictionless.

A basic source of a players cost from haggling comes from the twin facts that

bargaining is time consuming and that time is valuable to the player In Section 4 below,

Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS)

FUNDAMENTAL ECONOMICS Vol. I - The Economics of Bargaining - Abhinay Muthoo

we shall discuss the role of the players degrees of impatience on the outcome of

bargaining. A key principle that will be discussed is that a players bargaining power is

higher the less impatient that player is relative to the other negotiator. For example, in

the exchange situation described above, the price at which Aruna sells her house will be

higher the less impatient she is relative to Mohan. Indeed, patience confers bargaining

power.

U

SA N

M ES

PL C

E O

C E

H O

AP L

TE SS

R

S

A person who has been unemployed for a long time is typically quite desperate to find a

job, and may be willing to accept work at almost any wage. The high degree of

impatience of the long-term unemployed can be exploited by potential employers, who

may thus obtain most of the gains from employment. As such, an important role of

minimum wage legislation would seem to be to strengthen the bargaining power of the

long-term unemployed. In general, since a player who is poor is typically more eager to

strike a deal in any negotiations, poverty (by inducing a larger degree of impatience)

adversely affects bargaining power. No wonder, then, that the richer nations of the

world often obtain relatively better deals than the poorer nations in international trade

negotiations.

Another potential source of friction in the bargaining process comes from the possibility

that the negotiations might breakdown into disagreement because of some exogenous

and uncontrollable factors. Even if the possibility of such an occurrence is small, it

nevertheless may provide appropriate incentives to the players to compromise and reach

an agreement. The role of such a risk of breakdown on the bargaining outcome is

discussed in Section 5.

In many bargaining situations, the players may have access to outside options and/or

inside options. For example, in the exchange situation described above, Aruna may

have a nonnegotiable (fixed) price offer on her house from another buyer; and, she may

derive some utility (or benefit) while she lives in it. The former is her outside option,

while the latter is her inside option. When, and if, Aruna exercises her outside option,

the negotiations between her and Mohan terminate forever in disagreement. In contrast,

her inside option is the utility per day that she derives by living in her house while she

temporarily disagrees with Mohan over the price at which to trade. As another example,

consider a married couple who are bargaining over a variety of issues. Their outside

options are their payoffs from divorce, while their inside options are their payoffs from

remaining married but without much cooperation within their marriage. The role of

outside options on the bargaining outcome is discussed in Section 6, while the role of

inside options is discussed in Section 7.

Important questions addressed in Sections 47 are why, when, and how to apply Nashs

bargaining solutionthe latter is described and studied in Section 3. It is shown that

under some circumstances, when appropriately applied, Nashs bargaining solution

describes the outcome of a variety of bargaining situations. These results are especially

important and useful in applications, since it is often convenient for applied economic

and political theorists to describe the outcome of a bargaining situationwhich may be

one of many ingredients of their economic modelsin a simple (and tractable) manner.

An important determinant of the outcome of bargaining is the extent to which

Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS)

FUNDAMENTAL ECONOMICS Vol. I - The Economics of Bargaining - Abhinay Muthoo

information about various variables (or factors) are known to all the parties in the

bargaining situation. For example, the outcome of unionfirm wage negotiations will

typically be influenced by whether or not the current level of the firms revenue is

known to the union. The role of such asymmetric information on the bargaining

outcome is studied in Section 8.

In the preceding chapters, the focus is on one-shot bargaining situations. In Section 9,

we study repeated bargaining situations in which the players have the opportunity to be

involved in a sequence of bargaining situations. We conclude in Section 10.

U

SA N

M ES

PL C

E O

C E

H O

AP L

TE SS

R

S

(It may be noted that a bargaining situation is a game situation in the sense that the

outcome of bargaining depends on both players bargaining strategies: whether or not an

agreement is struck, and the terms of the agreement (if one is struck), depend on both

players actions during the bargaining process. It is therefore natural to study bargaining

situations using the methodology of game theory (see Game Theory).)

3. The Nash Bargaining Solution

A bargaining solution may be interpreted as a formula that determines a unique outcome

for each bargaining situation in some class of bargaining situations. In this section, we

introduce the bargaining solution created by John Nash. (Nashs bargaining solution and

the concept of a Nash equilibrium are unrelated concepts, other than the fact that both

concepts are the creations of the same individual.) The Nash bargaining solution is

defined by a simple formula, and it is applicable to a large class of bargaining

situationsthese features contribute to its attractiveness in applications. However, the

most important reason for studying and applying the Nash bargaining solution is that it

possesses sound strategic foundations: several plausible (game-theoretic) models of

bargaining vindicate its use. These strategic bargaining models will be studied in later

sections, where we shall address the issues of why, when, and how to use the Nash

bargaining solution. A prime objective of the current section, on the other hand, is to

develop a thorough understanding of the definition of the Nash bargaining solution,

which should facilitate its characterization and use in any application.

Two players, A and B, bargain over the partition of a cake (or surplus) of size , where

> 0. The set of possible agreements is X = ( x A , xb ) : 0 x A and x B = x A ,

where xi is the share of the cake to player i (i = A, B). For each xi [0, ], Ui(xi) is

player is utility from obtaining a share xi of the cake, where player is utility function

Ui : [0, ] is differentiable, strictly increasing, and concave. If the players fail to

reach an agreement, then player i obtains a utility of di, where di Ui(0). There exists

an agreement x X such that UA(x) > dA and UB(x) > dB, which ensures that there exists

a mutually beneficial agreement.

The utility pair d = (dA, dB) is called the disagreement point. In order to define the Nash

bargaining solution of this bargaining situation, it is useful to first define the set of

possible utility pairs obtainable through agreement. For the bargaining situation

described above, = {(uA, uB): there exists x X such that UA(xA) = uA and

uB(xB) = uB}.

Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS)

FUNDAMENTAL ECONOMICS Vol. I - The Economics of Bargaining - Abhinay Muthoo

Fix an arbitrary utility uA to player A, where uA [UA(0), UA( )]. From the strict

monotonicity of Ui, there exists a unique share xA [0, ] such that UA(xA) = uA; that

is, xA = UA-1(uA), where UA-1 denotes the inverse of UA. Hence:

g ( u A ) U B U A1 ( u A )

(1)

is the utility player B obtains when player A obtains the utility uA. It immediately

follows that:

= {( u A , uB ) : U A ( 0 ) u A U A ( ) and u B = g ( u A )}.

(2)

The Nash bargaining solution (NBS) of the bargaining situation described above is the

unique pair of utilities, denoted by u AN , u BN , that solves the following maximization

problem:

U

SA N

M ES

PL C

E O

C E

H O

AP L

TE SS

R

S

max

( u A ,uB )

( u A d A ) ( uB d B )

(3)

where:

{( u A , u B ) : u A d A and u B d B } {( u A , u B ) : U A ( 0 ) u A U A ( )

u B = g ( u A ) , u A d A and u B d B }.

(4)

The maximization problem stated above has a unique solution, because the maximand

(u A d A )(u B d B ) which is referred to as the Nash productis continuous and

strictly quasiconcave, g is strictly decreasing and concave, and the set is nonempty.

Hence, the Nash bargaining solution is the unique solution to the following pair of

equations:

g(u A ) =

uB d B

and u B = g ( u A )

uA d A

(5)

where g denotes the derivative of g.

Example 1 (Split the Difference Rule)

Suppose UA(xA) = xA for all xA [0, ] and UB(xB) = xB for all xB [0, ]. This means

that for each uA [0, ], g(uA) = - uA, and di 0 (i = A, B). It follows from Eq. (5)

that:

Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS)

FUNDAMENTAL ECONOMICS Vol. I - The Economics of Bargaining - Abhinay Muthoo

u AN = d A +

1

1

( d A d B ) and uBN = d B + ( d A d B )

2

2

(6)

which may be given the following interpretation. The players agree first to give player i

(i = A, B) a share di of the cake (which gives player i a utility equal to the utility that i

obtains from not reaching agreement), and then they split equally the remaining cake

- dA - dB. Notice that players is share is strictly increasing in di and strictly

decreasing in dj (j i).

Example 2 (Risk Aversion)

Suppose U A ( x A ) = x A for all x A [0, ] , where 0 < < 1, UB(xB) = xB for all xB [0,

U

SA N

M ES

PL C

E O

C E

H O

AP L

TE SS

R

S

], and dA = dB = 0. This means that for each uA [0, ], g(uA) = u A . Using Eq.

(5), it is easy to show that the shares x AN and x BN of the cake in the NBS allotted to

players A and B, respectively, are as follows:

1

x AN =

N

and xB =

1+

1+

(7)

As decreases, x AN and x BN increase. In the limit, as 0, x AN 0 and x BN 1 .

Player B may be considered risk neutral (since Bs utility function is linear), while

player A is risk averse (since As utility function is strictly concave), where the degree

of As risk aversion is decreasing in . Given this interpretation of the utility functions,

it has been shown that player As share of the cake decreases as A becomes more risk

averse.

3.1 An Application to Bribery and the Control of Crime

An individual C decides whether or not to steal a fixed amount of money , where

> 0. If C steals the money, then the probability is that C is caught by a policeman

P. The policeman is corruptible, and bargains with the criminal over the amount of bribe

b that C gives P in return for not reporting the crime to the authorities. The set of

possible agreements is the set of possible divisions of the stolen money, which

(assuming money is perfectly divisible) is {( - b, b): 0 b }. The policeman

reports the criminal to the authorities if and only if they fail to reach agreement. In that

eventuality, the criminal pays a monetary fine. The disagreement point (dC, dP) = (

(1 - ), 0), where [0,1], is the penalty rate. The utility to each player from

obtaining x units of money is x.

It immediately follows that the NBS is u CN = [1 ( 2)] and u PN = / 2 . The bribe

associated with the NBS is bN = /2. Notice that, although the penalty is never paid

to the authorities, the penalty rate influences the amount of bribe that the criminal pays

the corruptible policeman.

Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS)

FUNDAMENTAL ECONOMICS Vol. I - The Economics of Bargaining - Abhinay Muthoo

U

SA N

M ES

PL C

E O

C E

H O

AP L

TE SS

R

S

Given this outcome of the bargaining situation, we now address the issue of whether or

not the criminal commits the crime. The expected utility to the criminal from stealing

the money is [1 - ( /2)] + (1 - ) , because with probability , C is caught by

the policeman (in which case the utility is u CN ) and with probability (1 - ), C is not

caught by the policeman (in which case C keeps all of the stolen money). Since the

utility from not stealing the money is zero, the crime is not committed if and only if

[1 - ( /2)] 0. That is, since > 0, the crime is not committed if and only if

0. Since < 1 and 0 < 1 implies that < 1, for any penalty rate

[0,1] and any probability < 1 of being caught, the crime is committed. This

analysis thus vindicates the conventional wisdom that if penalties are evaded through

bribery, then they have no role in preventing crime.

TO ACCESS ALL THE 33 PAGES OF THIS CHAPTER,

Visit: http://www.eolss.net/Eolss-sampleAllChapter.aspx

Bibliography

Muthoo A. (1999). Bargaining Theory with Applications. 357 pp. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press. [This presents a systematic and unified treatment of the modern theory of bargaining.]

Nash J. (1950). The Bargaining Problem. Econometrica 18, 155-162.

Nash J. (1953). Two-Person Cooperative Games. Econometrica 21, 128-140. [These two classic papers

by John Nash laid important foundations for bargaining theory.]

Rubinstein A. (1982). Perfect Equilibria in a Bargaining Model. Econometrica 50, 97-110. [This classic

presents the canonical, formal model of strategic bargaining that lies at the core of modern bargaining

theory.]

Schelling T. C. (1960). The Strategy of Conflict. 308 pp. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University

Press. [This is a classic that contains many important ideas and intuitive arguments about bargaining.]

Biographical Sketch

Abhinay Muthoo is professor of economics at the University of Essex. He has previously taught at the

London School of Economics (LSE) and the University of Bristol. He was educated at the LSE and the

University of Cambridge. Professor Muthoo has published papers on bargaining theory, amongst other

topics, in the worlds top academic journals. His recent book on bargaining theory published in 1999 by

Cambridge University Press has received noteworthy acclaim from leading economists and academicians.

Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS)

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Negotiation Skills: Essentials, Preparation, Strategies, Tactics & Techniques: Volume 5Da EverandNegotiation Skills: Essentials, Preparation, Strategies, Tactics & Techniques: Volume 5Nessuna valutazione finora

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Applications of Behavioral EconomicsDa EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Applications of Behavioral EconomicsNessuna valutazione finora

- Study Guide Module 2Documento12 pagineStudy Guide Module 2sweta_bajracharyaNessuna valutazione finora

- What Are The Methods of Conflict AnalysisDocumento16 pagineWhat Are The Methods of Conflict Analysisleah100% (1)

- The Reasons For Wars - An Updated Survey: Matthew O. Jackson and Massimo MorelliDocumento34 pagineThe Reasons For Wars - An Updated Survey: Matthew O. Jackson and Massimo MorelligerosaNessuna valutazione finora

- Tina ModelDocumento19 pagineTina ModelAravind MenonNessuna valutazione finora

- Bargaining Theory in Internatonal RelatonsDocumento13 pagineBargaining Theory in Internatonal RelatonsRohan ChoudharyNessuna valutazione finora

- International LawDocumento45 pagineInternational LawFauzan RasipNessuna valutazione finora

- Effective Negotiation - Fundamentals of Integrative Negotiation and Distributive NegotiationDocumento8 pagineEffective Negotiation - Fundamentals of Integrative Negotiation and Distributive NegotiationShekin AzizNessuna valutazione finora

- Successful Negotiation: Communicating effectively to reach the best solutionsDa EverandSuccessful Negotiation: Communicating effectively to reach the best solutionsNessuna valutazione finora

- Negotiating the Impossible: How to Break Deadlocks and Resolve Ugly ConflictsDa EverandNegotiating the Impossible: How to Break Deadlocks and Resolve Ugly ConflictsNessuna valutazione finora

- Negociacion 3Documento18 pagineNegociacion 3Manuel Alejandro Roa RomeroNessuna valutazione finora

- Chap 3Documento11 pagineChap 3Quỳnh GiaoNessuna valutazione finora

- Negotitation SolutionDocumento10 pagineNegotitation SolutionFarah TahirNessuna valutazione finora

- Locked-In Range Analysis: Why Most Traders Must Lose Money in the Futures Market (Forex)Da EverandLocked-In Range Analysis: Why Most Traders Must Lose Money in the Futures Market (Forex)Valutazione: 1 su 5 stelle1/5 (1)

- The Negotiation Process and International Economic OrganizationsDocumento30 pagineThe Negotiation Process and International Economic OrganizationskhairitkrNessuna valutazione finora

- Abhinay Muthoo Bargaining Theory With APDocumento5 pagineAbhinay Muthoo Bargaining Theory With AP姚望Nessuna valutazione finora

- NegotiationDocumento30 pagineNegotiationvinodshukla25Nessuna valutazione finora

- Carrell CH 03 FinalDocumento29 pagineCarrell CH 03 FinalLam Wai KitNessuna valutazione finora

- Summary of Getting to Yes: by Roger Fisher, William Ury, and Bruce Patton | Includes AnalysisDa EverandSummary of Getting to Yes: by Roger Fisher, William Ury, and Bruce Patton | Includes AnalysisNessuna valutazione finora

- Summary of Getting to Yes: by Roger Fisher, William Ury, and Bruce Patton | Includes AnalysisDa EverandSummary of Getting to Yes: by Roger Fisher, William Ury, and Bruce Patton | Includes AnalysisNessuna valutazione finora

- Negotiation As The Art of The Deal Autor Matthew O. Jackson, Hugo F. Sonnenschein, Yiqing Xing, Christis G. Tombazos yDocumento90 pagineNegotiation As The Art of The Deal Autor Matthew O. Jackson, Hugo F. Sonnenschein, Yiqing Xing, Christis G. Tombazos yBryan BaringNessuna valutazione finora

- CONFLICT RESOLUTION Individual AssignmentDocumento8 pagineCONFLICT RESOLUTION Individual AssignmentCaxton mwashitaNessuna valutazione finora

- Jules ColemanDocumento34 pagineJules ColemanleonidaspartiNessuna valutazione finora

- Jackson Morelli 2011 ReasonsDocumento24 pagineJackson Morelli 2011 Reasonsbandoss 123Nessuna valutazione finora

- Less Pain, Same Gain: The Effects of Priming Fairness in Price NegotiationsDocumento18 pagineLess Pain, Same Gain: The Effects of Priming Fairness in Price NegotiationsAmir Zaib AbbasiNessuna valutazione finora

- On The Strategic Disclosure of Feasible Options in BargainingDocumento58 pagineOn The Strategic Disclosure of Feasible Options in BargainingsosannaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Limits of Noise Trading - An Experimental AnalysisDocumento48 pagineThe Limits of Noise Trading - An Experimental AnalysisDwight ThothNessuna valutazione finora

- Thompson 1990 PDFDocumento18 pagineThompson 1990 PDFlucianaeuNessuna valutazione finora

- Negotiation Skills Sep17Documento10 pagineNegotiation Skills Sep17Ayjemal SapargeldiyevaNessuna valutazione finora

- Negotiating Trade Agreements: 02 - Ch. 2 - 17-36 8/14/06 2:32 PM Page 17Documento19 pagineNegotiating Trade Agreements: 02 - Ch. 2 - 17-36 8/14/06 2:32 PM Page 17desNessuna valutazione finora

- Comm. and Reneg. SSRN-Id581721 - 2Documento27 pagineComm. and Reneg. SSRN-Id581721 - 2Lck Er LogickalNessuna valutazione finora

- Econ Colla LJDocumento90 pagineEcon Colla LJCarlos SaavedraNessuna valutazione finora

- Elster Arguing and BargainingDocumento22 pagineElster Arguing and BargainingZaidy Sogbi ♣Nessuna valutazione finora

- Negotiation and Co-Creation: A Comparative Study of Decision-Making ProcessesDa EverandNegotiation and Co-Creation: A Comparative Study of Decision-Making ProcessesNessuna valutazione finora

- Contracts As Reference Points - Oliver HartDocumento48 pagineContracts As Reference Points - Oliver HartGustavoNessuna valutazione finora

- Futures Trading Strategies: Enter and Exit the Market Like a Pro with Proven and Powerful Techniques For ProfitsDa EverandFutures Trading Strategies: Enter and Exit the Market Like a Pro with Proven and Powerful Techniques For ProfitsValutazione: 1 su 5 stelle1/5 (1)

- Adams ModellingDocumento15 pagineAdams ModellingkimimahestaNessuna valutazione finora

- HRM Assignment 1Documento5 pagineHRM Assignment 1Laddie LMNessuna valutazione finora

- Difference Between Selling and Marketing: SellingDocumento6 pagineDifference Between Selling and Marketing: SellingAvinash JoshiNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction To Institutional EconomicsDocumento4 pagineIntroduction To Institutional EconomicsMunish AlaghNessuna valutazione finora

- Conflict Theory Journal ZartmanDocumento12 pagineConflict Theory Journal ZartmanellaNessuna valutazione finora

- Trade Wars What Do They Mean Why Are They Happening Now What Are The CostsDocumento22 pagineTrade Wars What Do They Mean Why Are They Happening Now What Are The CostsLutfia InggrianiNessuna valutazione finora

- Little Book of Strategic Negotiation: Negotiating During Turbulent TimesDa EverandLittle Book of Strategic Negotiation: Negotiating During Turbulent TimesNessuna valutazione finora

- Coase TheoremDocumento5 pagineCoase TheoremanemoskkkNessuna valutazione finora

- Multilateral Bargaining With Concession Costs: Guillermo Caruana, Liran Einav and Daniel QuintDocumento30 pagineMultilateral Bargaining With Concession Costs: Guillermo Caruana, Liran Einav and Daniel QuintkacongmarcuetNessuna valutazione finora

- NegotiationDocumento36 pagineNegotiationDaneyal MirzaNessuna valutazione finora

- Testament and Possibly An Original Meaning of The GreekDocumento24 pagineTestament and Possibly An Original Meaning of The GreekJundelle BagioenNessuna valutazione finora

- Bargaining and Market Behavior in Jerusalem, Ljubljana, Pittsburgh, and Tokyo - An Experimental Study PDFDocumento29 pagineBargaining and Market Behavior in Jerusalem, Ljubljana, Pittsburgh, and Tokyo - An Experimental Study PDFDiogo Marcelino Campos TeixeiraNessuna valutazione finora

- Internationa L Relations: Saint Patrick's SchoolDocumento11 pagineInternationa L Relations: Saint Patrick's Schooldante fioraniNessuna valutazione finora

- The Pros and Cons of Getting To YesDocumento23 pagineThe Pros and Cons of Getting To YesNicky PetersNessuna valutazione finora

- How to Negotiate to Win Everytime: The negotiation tactics 101 textbook that will teach you influence & negotiating the sweet spot to get the most impossible& best terms for your business & yourselfDa EverandHow to Negotiate to Win Everytime: The negotiation tactics 101 textbook that will teach you influence & negotiating the sweet spot to get the most impossible& best terms for your business & yourselfNessuna valutazione finora

- Shivang K10Documento22 pagineShivang K10Shivang RawatNessuna valutazione finora

- 2.1 Limits of The ArbitrageDocumento3 pagine2.1 Limits of The ArbitragensmkarthickNessuna valutazione finora

- International Negotiations PlanDocumento49 pagineInternational Negotiations PlanMariia KuchynskaNessuna valutazione finora

- c3 PDFDocumento42 paginec3 PDFmnaka19837343Nessuna valutazione finora

- Hernanrobins V2march52017Documento86 pagineHernanrobins V2march52017mnaka19837343Nessuna valutazione finora

- Duffie Jep Prone To Fail December8 2018Documento45 pagineDuffie Jep Prone To Fail December8 2018mnaka19837343Nessuna valutazione finora

- Political Economy Lecture NotesDocumento569 paginePolitical Economy Lecture NotesgiberttiNessuna valutazione finora

- PHD Course Empirical IO Wolak Stockholm 2010 - Course Outline - May 3Documento3 paginePHD Course Empirical IO Wolak Stockholm 2010 - Course Outline - May 3mnaka19837343Nessuna valutazione finora

- MPRA Paper 10861Documento27 pagineMPRA Paper 10861mnaka19837343Nessuna valutazione finora

- Political Economy Lecture NotesDocumento569 paginePolitical Economy Lecture NotesgiberttiNessuna valutazione finora

- Options Market StructureDocumento17 pagineOptions Market StructureAnkit VyasNessuna valutazione finora

- Project 3 ACCT 610Documento11 pagineProject 3 ACCT 610Ohemaa EsteeNessuna valutazione finora

- Interest Rates Derivatives Trading Group WithinDocumento1 paginaInterest Rates Derivatives Trading Group Withinapi-26612535Nessuna valutazione finora

- Exercise 6-2: Revenue RecognitionDocumento34 pagineExercise 6-2: Revenue RecognitionPaulina CardenasNessuna valutazione finora

- Images Ebook Sample - Assessment.questions Ceilli Ceilli - English Ceilli - Set2Documento26 pagineImages Ebook Sample - Assessment.questions Ceilli Ceilli - English Ceilli - Set2phyliciayapNessuna valutazione finora

- Sec Form 4Documento1 paginaSec Form 4Nick WeigNessuna valutazione finora

- The Insider AdvantageDocumento21 pagineThe Insider Advantagehitesh gamiNessuna valutazione finora

- PFRS 2 Share-Based PaymentDocumento21 paginePFRS 2 Share-Based PaymenteiraNessuna valutazione finora

- Equatorial Realty Dev't Inc. and Carmelo & Bauermann, Inc. vs. Mayfair Theaters Case DigestsDocumento6 pagineEquatorial Realty Dev't Inc. and Carmelo & Bauermann, Inc. vs. Mayfair Theaters Case DigestsJeremiah TrinidadNessuna valutazione finora

- SMM148 Theory of Finance QuestionsDocumento5 pagineSMM148 Theory of Finance Questionsminh daoNessuna valutazione finora

- Foreign Currency Derivatives and Swaps: QuestionsDocumento6 pagineForeign Currency Derivatives and Swaps: QuestionsCarl AzizNessuna valutazione finora

- CH 13Documento28 pagineCH 13lupavNessuna valutazione finora

- Mba III Investment Management m2Documento18 pagineMba III Investment Management m2777priyankaNessuna valutazione finora

- HGdghdhaghgadDocumento9 pagineHGdghdhaghgadJohn Brian D. SorianoNessuna valutazione finora

- Bear Call SpreadDocumento6 pagineBear Call SpreadkotharidevangiNessuna valutazione finora

- DCF / Valuation Case Study: Jazz Pharmaceuticals (JAZZ) - Stock Pitch OutlineDocumento2 pagineDCF / Valuation Case Study: Jazz Pharmaceuticals (JAZZ) - Stock Pitch OutlineSumalya BhattaacharyaaNessuna valutazione finora

- Turnaround Strategies - Charles HoferDocumento14 pagineTurnaround Strategies - Charles HoferSandeep PandeyNessuna valutazione finora

- Currency Derivatives: For Use With International Financial Management, 3e Jeff Madura and RolandDocumento37 pagineCurrency Derivatives: For Use With International Financial Management, 3e Jeff Madura and Rolandياسين البيرنسNessuna valutazione finora

- Multinational Business Finance 12th Edition Slides Chapter 08Documento44 pagineMultinational Business Finance 12th Edition Slides Chapter 08Alli TobbaNessuna valutazione finora

- Auto CretDocumento5 pagineAuto CretMohamed MahmoudNessuna valutazione finora

- Question and Answer - 52Documento31 pagineQuestion and Answer - 52acc-expertNessuna valutazione finora

- Problem 14-4 (IAA)Documento8 pagineProblem 14-4 (IAA)NIMOTHI LASE0% (1)

- Active Soa TemplateDocumento38 pagineActive Soa TemplatejamesNessuna valutazione finora

- Home Assignmant # 1Documento2 pagineHome Assignmant # 1Talha Nasir50% (2)

- 12th BM Paper - 1 - HL (Set - C)Documento3 pagine12th BM Paper - 1 - HL (Set - C)Mohd Bilal TariqNessuna valutazione finora

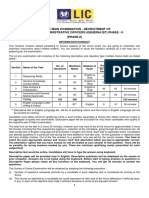

- On-Line Main Examination - Recruitment of Assistant Administrative Officers (Generalist) Phase - Ii (Phase-Ii)Documento7 pagineOn-Line Main Examination - Recruitment of Assistant Administrative Officers (Generalist) Phase - Ii (Phase-Ii)Naveen KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Alternative Obligation PaperDocumento31 pagineAlternative Obligation PaperRicaNessuna valutazione finora

- ProblemSet2 SolutionsDocumento3 pagineProblemSet2 SolutionsSimonNessuna valutazione finora

- (PA-1) 46. LeasesDocumento19 pagine(PA-1) 46. LeasesIvan VillafuerteNessuna valutazione finora

- Glossary 30 Day Trading BootcampDocumento9 pagineGlossary 30 Day Trading Bootcampschizo mailNessuna valutazione finora