Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

F - Edited - Dr. Anila Amber Malik & Erum Riaz

Caricato da

Waqas MurtazaDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

F - Edited - Dr. Anila Amber Malik & Erum Riaz

Caricato da

Waqas MurtazaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Journal of European Studies

Freud: The Sufi Within

Anila Amber Malik

Erum Riaz

Abstract

This article strives to draw parallels between the teachings of

Sigmund Freud and that of Sufi philosophers such as Rumi,

Ghazali, Farabi, Al Kindi, Ibn Rashd, Ibn Badjdja, Idries Shah,

Burton and that of quantum physics in the writings of Hawking.

Parallels are drawn between the Romantic era and its reflection in

Freuds writings, in the form of the intangible, dreams, the

unconscious and the study of Orientalism. The idea of the murid

and morad is found in Freudian analytical framework where the

client in the guise of the murid starts the process of transference

with his teacher (morad or psychoanalyst). Not only is the inward

exploration of man that forms the backbone of Freuds theory and

Sufi philosophy examined; the use of similes and metaphors in

Freuds works and that of the Sufi tradition is also compared. Thus

the idea of quiet happiness expounded by Freud and of ultimate

happiness by Ibn Badjdja are seen as strikingly similar. The nafs

of the Sufi tradition and the Freudian id, ego and super ego also

have a startling similarity. The authors explore how Ghazalis

theory of the mind as a mirror, and Freuds defense mechanisms

are comparable. Freuds discussion about the Jewish nature of his

mysticism in the later part of his life is also explored. The authors,

studying parallels between Sufism and Freud do not ignore the fact

that though Sufism seems to be infused with spiritual thought, it

does not ignore the sexual aspect of the human being, which is

apparent in Rumis writings. Just as the Sufi seeks the truth, Freud

too leaves no stone unturned to find it, which is apparent in his

forays into literature. What the Sufis had started was given impetus

by Freuds vision. Far from being paranoid about sexuality, he

upholds it as an integral part of the human nature. At the same time

119

Journal of European Studies

Freud was deeply spiritual; believing that man could attain dignity,

love and happiness.

Introduction

Even though you tie a hundred knots- the string remains one.

Rumi

In order to understand Freuds theories one has to go back in time,

to the period which gave birth to one of the most fertile minds in

the history of man, a man who changed the face of psychology

with his theories. In particular, he completely altered the concept

of how an individual viewed and understood himself. Freud was

born in Freiberg, Moravia (now known as the Czech Republic) in

the year 1856, to Jewish parents. He then moved to Vienna at the

age of three, where he stayed till the invasion by Hitlers troops in

1938, when he moved to London where he lived till his death in

1939. Initially, Freud studied medicine but he knew that being

Jewish would impede his rise in the field of medicine. Besides, his

father was becoming infirm and unable to provide the requisite

finances to help him in his education. Thus, he started working at a

Viennese hospital to pay his way through, and then later through a

grant got the opportunity to work with Charcot and study hypnosis.

This introduced him to the field of psychiatry and diseases of the

mind.1 From Breuer he learnt the technique of catharsis, leading

him to the concept of free association. He later went on to publish

Studies on Hysteria with Breuer.2 His famous works are The

Interpretation of Dreams (1900/1953), Psychopathology of

Everyday Life (1901/1960), Three Essays on the Theory of

Sigmund Freud, An Autobiographical Study, the Standard Edition (New York:

Norton, 1925).

2

J. Breuer & S. Freud, Studies on Hysteria, in James Strachey (trans.), The

Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud 2

(London: Hogarth Press, 1895 / 1955).

120

Journal of European Studies

Sexuality (1905/1953b) and Jokes and their Relation to the

Unconscious (1905/1960).3

Freud was born when the Romantic Movement was at its zenith,

and the vagaries of scientific discovery were being talked about

with passionate interest in intellectual circles. Freud being the

product of his times, showed a keen interest in the Romantic

subjects, in German Naturphilosophie, Jewish philosophers, and

humanisms philosophy of the experience of each person, and of

his being an individual.4

Romanticism explored the acceptance of the intangible and how it

affected the human psyche. Freud was undoubtedly a product of

those times when the intellectual environment in Germany evoked

discussion on psychological introversion in literature and art,

which related strongly to the idea of Strum and Drang (Storm and

Stress). This period talked simultaneously of the truthfulness of

feelings, genuineness in conduct and ideas such as Orientalism and

spirituality. The concept of dreams having a connection with the

unconscious was given profound thought and significance in the

Romantic era.5

What is startling is the similarities that Freud shares with

philosophers who go further back in time, to the year 1207 (A.D.),

which saw the birth of one of the greatest thinkers, Jalaluddin

Rumi, in Balkh, Khorasan (Persia). Rumi was a great mystical

Jess Feist & Gregory J. Feist, Theories of Personality (New York: McGraw

Hill, 2002), 17-18, 21-22.

4

Tina Gianoulis & Ava Rose, Sigmund Freud, St.James Encyclopedia of Pop

Culture. Available from http://findarticles.com/articles/mi_gl epc/is_bio/ai_

2419200430/.2002.

5

Philolog posted by Patrick Hunt, Goya, Friedrich and Romanticism:

Reification of Nature. Retrieved on May 21, 2010 from

http://traumwerk.stanford.edu/philolog/2006/04/goya_friedrich_and_romantic

ism_1.html

121

Journal of European Studies

poet. His intellectual life seems to have been divided into different

eras, where he sought and found mystical communion with a

Perfect Man. This was reflected in Rumis devotion to Shamul

din of Tabriz, a wandering dervish in whom Rumi found his

spiritual twin.6 Amongst his contemporaries, Freud was

intellectually close to Charcot, Breuer, Jung, and Abraham. The

most intense of Freuds relationship was with Carl Jung. It is said

that both caused an intellectual and emotional upheaval in each

others lives. The first time that Freud and Jung met, was 1907,

which was the start of a great and productive professional and

personal relationship. Freud later came to regard Jung as his

potential successor and even called him the crown prince, who

would take over his mantle, in the psychoanalytical movement.

They were later to part on bitter terms but that did not take away

from the tumultuous and intense relationship they had shared with

each other akin to that of a master and his disciple.7

One finds that Rumis and Freuds thoughts are remarkably

similar. Rumi talks in his poem, the Diwan of Shams of Tabriz, of

internal consciousness, that upholds the eternal truth and not

organized religion with its rituals. Sufis are not into religious

rituals and the externalities of organized religion. The Sufi will not

travel from one country to another, or read hundreds of books to

find the truth or enlightenment. The Sufi will look inwards,

analyze his conscious and unconscious, like Freud has prescribed

in Psychoanalysis. The Sufis journey is within himself, the

answers to all his questions, lie within his heart.8 It was through

psychoanalysis and looking deep into his own psyche, that Freud

learnt the dynamics of the personality of man.

Reynold Nicholson, Rumi: Poet and Mystic (England: Oneworld Publications,

1998), 17-21.

7

Laurie Spurling (ed.), Freud and the Impact of Psychoanalysis, Sigmund

Freud: Critical Assessments (London and New York: Routledge, 1989), 3-4.

8

Idries Shah, The Sufis (London: W.H. Allen & Co. Ltd., 1977), x-xi, 135.

122

Journal of European Studies

According to Idries Shah (1977) a Sufi uses similes to elucidate his

point, which are taken from the world that is familiar. In this way

he can better convey his teachings to the populace. Here there is a

strong similarity between the Sufis and Freud. The latters Electra

and Oedipus theories explain the phenomenon of love for the

parent of the opposite sex. It was also the Sufis who propagated the

idea of conscious evolution, much before Darwin or Freud. This

concept refers to the conscious thought of man rather than men.9

But what is Sufism in its most intrinsic sense? According to Idries

Shah (1977)10, it is a spiritual sect found in almost all religions.

Their creed is the search for wisdom and attainment of

enlightenment through spiritualism. The Sufi is not bound by

traditions or books, and religious rituals are respected as long as

social harmony is preserved.11 Freud in Civilization and its

Discontents demonstrates the same thought processes when he

talks about religion being the bane and boon of human existence,

for even though it provides salvation or a palliative to the

common man, it also creates a herd instinct.12

Centuries before the birth of Freud, the world saw the golden age

of the Arab / Muslim civilization, where Muslim philosophers like

Ghazali, Farabi, Al Kindi, Ibn Rashd, Hunain bin Ishaq explored

human consciousness. This was the age of the thinkers, the

adventurers into the realm of the unknown. This was also the age

when Sufism reached its peak. One of the most prolific of these

men was Al Ghazali. Abhu Hamid Mohammed Ibn Ghazali (10591111) who was born in Persia, was renowned for his treatise on the

meaning of life in his book The Alchemy of Happiness. He was

Ibid.

Ibid.

11

Ibid.

12

Sigmund Freud, Civilizations and its Discontents, in James Strachey

(trans.), Standard Edition (New York: W.W. Norton and Company,

1961/1989), 22-23.

10

123

Journal of European Studies

deeply influenced by Sufism and his teachings and doctrines were

very close to Judaism. When comparing Sigmund Freuds writings

with those of Al Ghazali one finds startling similarities. The first

and foremost are the terms used to describe human nature by

Ghazali namely: Qalb, which is the heart, which is found in man

and animal. It is the conscious, and is purported to be the

conscience of man. The second is the ruh which is the spirit and

holds the same meaning as qalb but is infused by the divine light.

The third is nafs (human urges) which could also be called the self;

this personifies desire and obsession, fury and excitement.

According to the Sufis this is the source of all evil. It represents

human ego but when it is in the grip of passion and vice it is called

nafsi ammara, when it is controlled by the conscience it is called

nafsi lauwama and when it has overcome passions and appetites

and is at peace it is called the peaceful self or nafsi mutmainna.

It is clear that Sigmund Freud was influenced by Ghazalis

doctrines when developing the theory of Id (nafsi ammara), ego

(nafsi lauwama) and super ego (nafsi mutmainna).13

According to Al Ghazali, man is said to hover between the realms

of the animal and the divine. The temperament of man comprises

four facets the animal, the vile, the devilish and the pure or

spiritual. Desire is symbolized by the pig for its cravings and

greed, the dog symbolizes ardour, for it uses brute force to gets its

way and harm others. It is Satan, who controls the pig and the dog;

thus blinding man to wisdom and all things good. Divine wisdom

is what is capable of controlling the three, but only when man lets

divine reason do its job, otherwise the animal, vile and the satanic

facets of man will take over and lead him to destruction.14

13

Al Ghazali, Abu Hamid Mohammed Ibn Ghazali, Dagobert D. Runes, A

Treasury of Philosophy (New York: Grolier, 1955), 37-38.

14

Ibid, 35.

124

Journal of European Studies

All these attributes are again similar to the Id, symbolized by the

lust, appetite, tyranny, fear, fury and pride of the pig, dog and satan

and also the destructive instinct.15 The ego (denoting the reality

principle) and super ego (denoting the idealistic or moralistic

principle) are symbolized by divine wisdom which propels man in

the right direction and infuses him with reason and faith.16 (Ibid)

Another aspect of Al Ghazalis theory is that of the mind of man

being akin to a mirror, which acts like a reflective surface.

However, sometimes the mirror is not able to reflect the true

image, owing to various impairments in processing the image. The

reasons could be, that there may be a functional problem with the

mirror or that there is some other mechanism at work, that is

preventing the formation of the image or- even that the object may

actually not be in the right location to be reflected. Another reason

could be, that there exists a barrier between the object and the

mirror itself or the former is placed in such a way that its position

is not identifiable, hence the mirror not being in a position to catch

the image is not able to reflect it.17 This is reminiscent of the

defence mechanisms of Freud, as in repression, introjection,

reaction formation, denial, sublimation, displacement; all processes

that occur due to faulty processing of information, to which the

mind is not averse.18 Freuds theory on personality or his

psychoanalytical theory is based on his perspectives on life - what

he felt and imagined. This was his relationship with his mother,

father and sibling; which led to the theory of the Oedipus complex

(his love for his mother and resentment against his father) and the

death instinct for his brother.

Ibn Badjdja or Avenpace (1138 A.D) presented a theory similar to

that of Al Ghazali when he talked about animal and human

15

Jess Feist, Theories of Personality, 33.

Ibid, 28-29.

17

Dagobert Runes, Al Ghazali, 35-36.

18

J. Feist, Theories of Personality, 34-39.

16

125

Journal of European Studies

activities. His book the Hermits Guide got tremendous acclaim.

Averroes and Moses of Narbonne (a Jewish thinker and writer)

were also influenced by it. Ibn Badjdja (Avenpace) talked of the

solitary man as attaining the ultimate happiness akin to Freuds use

of the term quiet happiness, when a person withdraws from

social contact and attains peace and ultimately contentment.19

In 1900, Sigmund Freud wrote there is a psychological technique

which makes it possible to interpret dreams, and that if the

procedure is employed every dream reveals itself as a psychical

structure which has a meaning and which can be inserted at an

assignable point in the mental activities of waking life.20 Freud

talks about childhood experiences forming part of the content that

dreams are made of as also believed by Hildebrandt21 and

Strumpell22 both, like Freud, stating that dreams enact events that

belong to our earliest years.23

Freud states in his book the Interpretation of Dreams, that dreams

are looked at as extraneous to ourselves and our consciousness and

that they are emanating from somewhere else, hence the statements

mir hat getraumt (German for I had a dream or in the literal

sense a dream came to me). However Freud views the dream life

not as a part of the external world detached and with no part of the

personality of the dreamer, rather he states that it is the

detachment from the outside world that forms the basis of

dreams. He pursues this idea with another profound analysis, that

sleep results in the individuals involuntary relinquishing of one of

his mental faculties, that of voluntary control. The sleeper now has

19

Sigmund Freud, Civilizations and its Discontents, 27.

S. Freud, Interpretation of Dreams, in J. Strachey (trans.), Standard Edition

(New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1967), 35,49,87.

21

F. W. Hildebrandt, Der Traum und seine Verwerthung furs Leben (Leipzig,

1985), 23.

22

L. Strumpell, Die Natur and Entstehung der Traume (Leipzig, 1877), 40.

23

Sigmund Freud, Interpretation of Dreams, 49.

20

126

Journal of European Studies

a lowered psychical efficiency, during the time that his dream

starts and ends. The conscious parts of his personality are no

longer standing like sentinels over his unconscious desires and

fears.24

Ibn El Arabi believed in reverie, that part of his consciousness

which is still active, which connects the Sufi with the supreme

reality or the truth, that which lies under the facade of conscious

thought and the external world. The dream then has familiar forms

from the external world but holds deeper meaning. Freud talked of

the purpose of dreams as being the axis of wish fulfillment and to

hold the truth behind the metaphors and similes taken from the

familiar.25 Similarly, Ibn El Arabi, implied that dreams fulfilled the

desire of the Sufi to attain the eternal truth.26

Richard Burton, an explorer and a Sufi wrote The Kasidah which is

considered one of the most remarkable creations representing the

best in Sufi literature in the West. In the Lay of the Higher Law,

Burton attributed the creation of the Kasidah to one Haji Abdul

Yazdi and called himself as a translator. He cites Hafiz and Omar

Khayyam, both Sufis, as ones who would divorce the old barren

Reason from his bed/And wed the Vine maid in her stead. Burton

believes that one who has a soul should probe deeply the vagaries

of the soul. The Sufi way is to question and to seek the truth, not

outside but in the inner recesses of the heart, mind and soul. Here it

is intimated that it is the soul specifically as it is supposed to reside

in the heart.27 Burton also talks of the inner consciousness of the

individual, and conscience was born when man had shed his fur,

24

Ibid, 87.

James Hopkins, The Interpretation of Dreams, in Jerome Neu (ed.), The

Cambridge Companion to Freud (Cambridge University Press, 1992), 96-97.

26

Idries Shah, The Sufis, 141.

27

Ibid, 249-52.

25

127

Journal of European Studies

his tail and pointed ears, referring to the animalistic tendency of

man which needs to be subjugated through divine reason.28

Javed Nurbukhsh29 in his article on Sufism and psychoanalysis

talks of aqle jozi (particular intellect) and aqle kolli (universal

intellect). Aqle jozi helps man in his everyday life and nafse

ammara can be controlled by it when this nafs becomes unruly and

can cause grievous harm to the individual or society. However it

cannot pave the way or help the Sufi in search of truth. When the

heart or qalb becomes cleansed of the nefarious duplicity of the

material world, then only is the perfect man formed and the truth

unveiled; hence heart consciousness is achieved which in turn

leads to the acquisition of the universal intellect.30

Nurbukhsh31 goes on to state that psychoanalysts believe that the

relationship that is forged between the analyst and the client is

imperative and results in transference. The client transfers all his

past experiences to the therapist. A novel relationship takes root.

This is akin to Er adat, where the hopeful (taleb) is on a quest to

find his master after he has comprehended that he himself is

incomplete. In order to become complete, the incomplete man

looks for a master and on finding him becomes his murid

(disciple). The master helps the murid attain perfection resulting in

the aspirant becoming a Perfect Man which is also called ens an-e

kamel. The tie that binds the murid to his master or morad is

called er adat, the literal meaning of which is to want or to will,

however in Sufism it implies the blending of the murids will with

his masters or morads.32

28

Ibid, 254-55.

Javed Nurbakhsh, Sufism and Psychoanalysis, International Journal of

Social Psychiatry 24. Retrieved on 16 May 2010 from

http://www.humanevol.com/doc200307151102.html.

30

Ibid.

31

Ibid.

32

Ibid.

29

128

Journal of European Studies

In the same way that the relationship between the murid and morad

evolves, so does that of the client and the psychoanalyst. The client

places all his trust in his analyst and thus the analyst takes the role

of the morad. The client (murid) then without conscious thought

starts to project the attributes of the ideal person on to the analyst

(morad), thus surrendering himself to him. He has to let go of his

defences, especially when Freud talks about free association one

of the techniques used in psychoanalysis and also the way the

analyst positions himself behind the patient or remains invisible to

the client. This not only helps the client let go of his inhibitions

creating the illusion of being by himself but also gives power to the

analyst, the latter having instigated the surrender of the client. We

can thus conclude that the transference reflects the clients need to

fulfill his desire to control his nafs e ammara while the love of

another individual that is the analyst (morad) leads to the break

from self love.33

Then comes the initiation which forms a link from one to the other,

which is what Freud introduced in his practice when he initiated

Jung into psychoanalysis, Jung had to reveal his inner self and

submit to Freuds psychical inquiry, thus rendering Freud as his

morad. He in turn was then given the task of acting as initiator to

others seeking the path of enlightenment.34

Whitehead35 defines spirituality as that part of the experience of

man where he tries to discover himself through individual

solitariness36 which is reminiscent of Freuds theory of quiet

happiness stated in his treatise on Civilization and its

33

Ibid.

Ibid.

35

Alfred North Whitehead, Religion in the Making (New York: Macmillan,

1926),16.

36

Gerald J. Gargiulo, Aloneness in Psychoanalysis and Spirituality,

International Journal of Psychoanalytic Studies 1 (2004): 36-37.

34

129

Journal of European Studies

Discontents.37 Solitude or individual solitariness allows the

individual to find his true self, through self discovery. But this self

discovery comes through self imposed retirement from public life

or going into a form of isolation.38

Donald Winnicott39 also talks about solitariness of the individual

being part of culture and religion, not to mention an intrinsic part

of psychoanalysis. Winnicott talks of the space that a person makes

for himself that isolates him from others. This is the space that a

psychoanalyst will trespass upon to get to the root of the

problem.40 According to Garguilo the capacity to be alone in the

presence of the other, is as we know, basic to feeling alive as well

as experiencing the world as emotionally significant.41 This

solitariness cannot be equated with loneliness. Interestingly, not

being able to inculcate in one the capability to be internally

alone, does lead to loneliness.42

Sufism intimates that one has to look inward in order to attain the

essence of the eternal truth, to be one with the spirit of the

universe. Whether it is Ghazali, Burton or Arabi or even Rumi, all

have professed to have looked inward to gain insight into

themselves investing their time into meditation and analysis of

ones inner being. According to Freud analysis leads the individual

to love and to work, Garguilo implies that such a goal will help an

individual transcend the ordinariness of his existence and become

less conscious of the self. The love that one feels is not the

narcissistic love that is selfish but the desire to bring happiness to

another, and being able to work implies internal efficacy. The fact

37

Sigmund Freud, Civilizations and its Discontents, 27.

Gargiulo, Aloneness in Psychoanalysis, 36.

39

Donald Winnicott, The Maturational Processes and the Facilitating

Environment (New York: International Universities Press, 1965),187.

40

Ibid.

41

Gargiulo, Aloneness in Psychoanalysis.

42

Ibid.

38

130

Journal of European Studies

that an individual in his solitariness becomes one not only with

himself but also with the world entails vitality and not

unawareness.43

Human dignity is the core of psychoanalysis and traditions of

spirituality (Sufism) , both of which employ special ways or

traditions to retain the inviolable in every individual. This

transcendence is an everyday transcendence44, which leaves us

open to experience our beings and the world, while retaining our

personal dignity. In the book A Brief History of Time, Stephen

Hawking45, talks about the whole universe as originating from a

vacuum. Quantum physics states that our realities comprise a

limitless universe of opportunities. Quantum physics should not be

underestimated in helping bridge the gap between spirituality and

psychoanalysis. Quantum physicists postulate that the world is a

plethora of realities that is intrinsic to each individual. This theory

describes how each individuals reality is his own- it is his

perception of the world. We see what we have been programmed

to see. Albert Einstein states that it is the theory that decides what

we can observe46, which is what any psychoanalyst will

corroborate.47

Freud talks about three conditions that can cause unhappiness, pain

and suffering. One comes from our body that is the vesicle of all

things physical, and which will eventually turn to dust and

nothingness, the second is the suffering that one undergoes, owing

to the destructive forces of the external world which wreak havoc

43

Ibid.

James S. Grotstein, Who Is the Dreamer Who Dreams the Dream? (NJ: The

Analytical Press, 2000).

45

Stephen Hawking, A Brief History of Time (New York: Bantam Books, 1988),

175.

46

Bruce Gregory, Inventing Reality (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1988),

199.

47

Gargiulo, Aloneness in Psychoanalysis, 38.

44

131

Journal of European Studies

in the lives of the human race and the last is the pain that is a

product of our relations with others. Freud contends that the

suffering from the last source is in fact the most profound and can

be debilitating, but is considered as a part of life. Thus man

assumes that just because there is an absence of pain he should be

happy and resign himself to the reality principle. Hence his task

becomes to avoid suffering, rather than the pursuit of pleasure.

And since the most suffering is garnered from ones relationships

with others, Freud states that man then gravitates towards

voluntary isolation which gives him the happiness of quietness.

According to Freud all suffering is nothing else than sensation; it

only exists in so far as we feel it, and we only feel it in

consequence of certain ways in which our organism is regulated.48

Janette Graetz Simmonds carried out a study entitled Being and

Potential: Psychoanalytic Clinicians Concepts of God and found

that out of the 25 participants in the study most concurred to God

being a force or an energy which is imminent and for most also

transcendent. Spirituality was perceived as having evolutionary

and moral scope to do with awareness of the cosmos and levels of

consciousness beyond the usual levels of understanding. 49

In direct contrast to Carl Jungs50 belief in mysticism, Freud though

not rejecting it, showed a marked tendency towards spirituality. On

the one hand he expresses the belief that spirituality was alien to

his theory of Id and Ego, while on the other he admits that he has

an illogical aspect in his personality revealed by the extensive self

48

Sigmund Freud, Introductory Lectures on Psycho-Analysis. John Riviere

trans. (London: 1961).

49

Janette G. Simmonds, Being and Potential: Psychoanalytic Clinicians

Concepts of God, International Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies

(2006). Retrieved on 11 May 2010 from www.interscience.wiley.com.DOI:

10.1002/aps.107.

50

Carl Jung, The Psychology of the Transference, Collected Works 16 (London:

Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1980).

132

Journal of European Studies

analysis that he put himself through. He called this the the

specifically Jewish nature of (his) mysticism. 51

Freud also might have been suffering from the guilt that is the lot

of the Christians and Jews for committing the murder of their

fathers so to speak, namely Christ and Moses. Freuds critics

maintain that he tried to disassociate himself from the Jewish

race in an unconscious bid to purge himself of the guilt that the

Jews carry with them, and which is deeply embedded in their

psyche. In his overt rejection of religious practices, Freud comes

across as using this rejection as a defense mechanism bordering on

reaction formation. The more he reacted against religion and

spirituality or mysticism the more one is convinced that Freud was

deeply spiritual. Psychoanalysis talks of the traditional Jewish term

teshuvah which means turning, here it is surmised that it is from a

destructive path that the individual is turning away from, towards a

peaceful and constructive course of action. Freud leans more

towards being a Gnostic than a traditional Jew.52

Gay has talked of Freuds character as reminiscent of the

intellectual and moral virtues found in the great teachers of olden

times. He also calls him an indefatigable tough-minded

investigator of lifes riddles, one who is on a quest for the

ultimate truth and mastery of the self or as Gay posited

conquest of the self.53 And is this not also reminiscent of the Sufi

thought of self mastery, of subjugating the nafs in man, of attaining

the divine truth?

51

Janette G. Simmonds, Being and Potential.

Michael Mack, The Savage Science: Sigmund Freud, Psychoanalysis, and

the History of Religion, Journal of Religious History 30 (2006): 332-339.

53

John E. Toews, Historicizing Psychoanalysis: Freud in His Time and for Our

Time, Journal of Modern History 63. Retrieved on 21 May 2010 from

http://www.jstor.org/pss/2938629.

52

133

Journal of European Studies

When Freud wrote Moses and Monotheism, the father of

psychoanalysis, or the agnostic had come back to the fold of

Judaism. From denying religion he had come a long way, he was

fighting for dear life with cancer; this might have pushed him into

the realm of religious studies and deeper introspection and finally

accepting his tryst with spirituality as merging finally into

determinism and belief in God. Freud stated that faith in Judaism is

based on a God who cannot be seen or touched who cannot be

brought upon to bear witness to his being. This pushes the concept

of faith and belief to its limits. Man is asked to believe in

something or someone that is intangible; he is encouraged to look

within himself to find the ultimate truth. The prohibition against

making an image of God the compulsion to worship a God whom

one cannot see, a sensory perception was given second place to

what may be called an abstract idea- a triumph of intellectuality

over sensuality. This concept of abstraction, Freud felt would

lead to a scheme of internalizing which he attributed to religion.54

In the book Civilization and its Discontents, Freud55, talks of

neuroticism as being due to societal pressures and the frustration

that these pressures give birth to. In order to prevent this from

happening he asserts that one should rid society of these demands

so that man can lead a life unburdened by practices that bind him

to cultural mores. In the Sufi tradition, it can be gleaned from

Rumi to Idries Shah that what is important for attaining

enlightenment is to look inwards for guidance or towards God;

society has very little part to play if any at all in the thinkers or

Sufis search for truth.

Even though he (Freud) was a proponent of the theory that sexual

promiscuity comes naturally to man; in marriage, he himself led a

54

Sigmund Freud, Moses and Monotheism, Katherine Jones, trans. (London:

Hogarth Press, 1939).

55

Freud, Civilizations and its Discontents.

134

Journal of European Studies

monogamous life with his wife. This fact is lent credence to in his

letter to Fliess in 1897 sexual excitement is no longer of use

for someone like me.56 This leads one to believe that he preferred

an ascetic life devoted to the pursuit of knowledge, practiced by

many in the Sufi tradition. 57

And when we talk of drawing parallels between Freud and Sufism,

it is not possible to separate sexuality, which is an intrinsic part of

psychoanalysis. However, Freud was not the only one talking of

eroticism, in Arab Sufi literature, Rumi is renowned for the

eroticism in his poetry. The Mathnawi is not only known for its

magnificent lyricism but has also gained notoriety for its explicit

sexual material. Tourage uses Lacans philosophical approach to

deduce the meaning of Rumis phallocentric esotericism and he

discovers the phallus to have arcane meanings, which are narrated

using imagery that is sexual.58 Sexuality and spirituality form an

important part of Sufi literature and though there might be a

prevalence of one theme more than the other, both play an

important role in the formulation of thought processes of not only

the great mystics but also of Freuds brand of mysticism.

Freud in his book The Future of an Illusion talks of an oceanic

feeling, one that seems to bind us with the universe in our

aloneness. Spirituality and psychoanalysis share the one significant

element that binds them forever that of looking for answers.

Sufism is the search for the eternal truth, God, the notion that if

one finds the answers to human existence one will be set free from

worldly cares. Both Psychoanalysis and spirituality or Sufism per

56

Paul Ferris, Dr. Freud: A Life (Washington, D.C: Counterpoint, 1997).

Feist, Theories of Personality, 22.

58

Mahdi Tourage, Rumi and the Hermeneutics of Eroticism. Retrieved on 17

May 2010 from http://www.thefreelibrary.com/Rumi+and+the+hermeneutics

+of+eroticism.(Brief+Article)(Book+Review)-a0174602267.

57

135

Journal of European Studies

se, are a quest for answers that will free the person from care and

will pave the way for true happiness.59

But it is not enough to talk of the thread of mysticism that runs

through Freuds writings. It is with great intensity that Freud says,

I am, of course speaking of the way of life which makes love the

center of everything, which looks for all satisfaction in loving and

being loved.60 This sentiment is also present in the mystic poetry

of Ibn El Arabi61:

Love is the creed I hold: wherever turn

His camels, love is still my creed and faith.

Conclusion

The debate whether Freud is religious or not can be answered in a

fairly straightforward manner, but that Freud was a hidden Sufi is

something that is open to discourse. Throughout his writings he

displays a profound knowledge of the inner workings of the mind

of the human being; his life revolved around the acquisition of

knowledge about the human psyche. He questioned and debated,

reiterated and retracted various theories that he had postulated. His

seduction theory could have become his Achilles heel but the rest

of his work was so deeply entrenched in sound theoretical

framework that to date it has been difficult to dislodge its

psychoanalytical premise.

Freud had his disciples in Jung and then Karl Abraham, who in

other words were to carry on his legacy of psychoanalysis. The

study of the human being which is fascinating in its complexity,

became more enthralling because Freud made it so. Freud was not

only influenced by the Sufi writings as is evident in his theories

59

Sigmund Freud, The Future of an Illusion, W. D. Robson-Scott, trans. (New

York: Horace Liveright, 1928).

60

Ibid, 32.

61

Shah, The Sufis, 145.

136

Journal of European Studies

about the unconscious and conscious, it was also the Sufis who

shared his openness about eroticism. Since Rumi could not have

known Freuds postulations, having being born way before his

(Freuds ) time, there is a probability of Sigmund Freud being

influenced by the Sufi writings of Rumi.

When the authors of this article began research on Freud and Sufi

thought, they had to follow their hunch that with a careful study of

both, the similarities between Freuds thought and Sufi traditions

could be found. And they were not disappointed. From scholars

like Neu, or Feist and Feist (in the Personality Theories) to Freuds

own writings such as the Interpretations of Dreams, Civilization

and its Discontents, and Savage Science the authors saw the mystic

in Freud. The dichotomy in Freud was evident; he was not only a

spiritualist, a philosopher, a weaver of stories, but also a man who

seized scientific psychological practice and revolutionized it with

his theory of the oedipal complex. He renounced religious

practices as inane and meant to keep man tethered to the bonds of

societal mores. Freud not only saw the beautiful in the mundane,

his prose is full of metaphors and similes, the mysterious and the

unseen. His theory of personality is his faith. He contends that an

individuals personality develops under the influence of the unseen

forces of dark and light present in man himself, which are

manifested in good and bad actions- which are sometimes covert

and at other times overt.

When Freud wrote about sexuality, it was not because he was

trying to offend, it was to rid himself and others of the guilt of

being a Jew and of the original sin which is an integral part of the

Jewish and Christian faiths. All he wanted was to break the chains

of shame, to which he could not reconcile himself. Freuds theory

was deeply personal to him, it was presented to the world after

intensive introspection and the unveiling of his deepest desires. For

this he had to overcome his own inhibitions. It was first and

foremost on himself, rather than anyone else that he applied

psychoanalysis. He was devoted to the intellectual pursuit that

137

Journal of European Studies

philosophers through the ages have been addicted to to seek

enlightenment on the world that exists within. According to

Stephen Hawking if we find an answer to the existence of man and

the universe it would be the ultimate triumph of human reasonfor then we would know the mind of God. 62

Shabistri put it most succinctly when he said: In an instant rise

from time and space. Set the world aside and become a world

within yourself.63

62

63

Stephen Hawking, A Brief History of Time, 175.

Shah, The Sufis, 206.

138

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Agrodok-series+No 24+urban+agriculture PDFDocumento78 pagineAgrodok-series+No 24+urban+agriculture PDFWaqas Murtaza100% (2)

- Freud and Jung - Alexander JacobDocumento30 pagineFreud and Jung - Alexander JacobWF1900Nessuna valutazione finora

- 2 Freud - S PsychoanalysisDocumento54 pagine2 Freud - S Psychoanalysisanon_450204524Nessuna valutazione finora

- THE TRANSPERSONAL REVOLUTION FundamentalDocumento59 pagineTHE TRANSPERSONAL REVOLUTION FundamentalRamon Enrique Hinostroza GutierrezNessuna valutazione finora

- 520l0553 PDFDocumento52 pagine520l0553 PDFVasil TsvetanovNessuna valutazione finora

- Research Methodology-2Documento14 pagineResearch Methodology-2Muhammad Obaid Ullah100% (2)

- MYTH, MIND AND METAPHOR On The Relation of Mythology and Psychoanalysis PDFDocumento15 pagineMYTH, MIND AND METAPHOR On The Relation of Mythology and Psychoanalysis PDFEcaterina OjogNessuna valutazione finora

- IbnTaymiyyah Theological EthicsDocumento361 pagineIbnTaymiyyah Theological EthicsDado Daki100% (1)

- Literature and PsychoanalysisDocumento290 pagineLiterature and PsychoanalysisGabriela Târziu100% (5)

- Freud A Collection of Critical Essays PDFDocumento431 pagineFreud A Collection of Critical Essays PDFDeivede FerreiraNessuna valutazione finora

- Freud on the Couch: A Critical Introduction to the Father of PsychoanalysisDa EverandFreud on the Couch: A Critical Introduction to the Father of PsychoanalysisValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2)

- The Question of God: C.S. Lewis and Sigmund Freud Debate God, Love, Sex, and the Meaning of LifeDa EverandThe Question of God: C.S. Lewis and Sigmund Freud Debate God, Love, Sex, and the Meaning of LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (16)

- Rightship Ship Inspection Questionnaire RISQDocumento177 pagineRightship Ship Inspection Questionnaire RISQИгорь100% (3)

- Four Hidden Matriarchs of Psychoanalysis: The Relationship of Lou Von Salome, Karen Horney, Sabina Spielrein and Anna Freud To Sigmund FreudDocumento8 pagineFour Hidden Matriarchs of Psychoanalysis: The Relationship of Lou Von Salome, Karen Horney, Sabina Spielrein and Anna Freud To Sigmund Freudaulia azizahNessuna valutazione finora

- Study Guide to the Introductory Lectures of Sigmund FreudDa EverandStudy Guide to the Introductory Lectures of Sigmund FreudNessuna valutazione finora

- Sigmund Freud and the Jewish Mystical TraditionDa EverandSigmund Freud and the Jewish Mystical TraditionValutazione: 2.5 su 5 stelle2.5/5 (5)

- The Mystical Roots of Psychoanalytic TheoryDocumento5 pagineThe Mystical Roots of Psychoanalytic TheorybarbayorgoNessuna valutazione finora

- Shamanism Archaic Techniques of EcstasyDocumento5 pagineShamanism Archaic Techniques of EcstasyHamidreza Motalebi0% (1)

- Schopenhauer and FreudDocumento27 pagineSchopenhauer and FreudGustavo AvendañoNessuna valutazione finora

- Rolling Bearings VRMDocumento2 pagineRolling Bearings VRMRollerJonnyNessuna valutazione finora

- Study Guide to a General Overview of Sigmund FreudDa EverandStudy Guide to a General Overview of Sigmund FreudNessuna valutazione finora

- Assembly Manual, Operation and Maintenance Round Vibrating Screen Model: Tav-Pvrd-120Documento15 pagineAssembly Manual, Operation and Maintenance Round Vibrating Screen Model: Tav-Pvrd-120Sandro Garcia Olimpio100% (1)

- Sr. IBS DAS Consultant EngineerDocumento4 pagineSr. IBS DAS Consultant EngineerMohamed KamalNessuna valutazione finora

- Industrial Training Report (Kapar Power Plant)Documento40 pagineIndustrial Training Report (Kapar Power Plant)Hakeemi Baseri100% (2)

- Eli ZaretskyDocumento21 pagineEli ZaretskylauranadarNessuna valutazione finora

- Revolution in Mind: The Creation of PsychoanalysisDa EverandRevolution in Mind: The Creation of PsychoanalysisValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (7)

- Freud and Monotheism: Moses and the Violent Origins of ReligionDa EverandFreud and Monotheism: Moses and the Violent Origins of ReligionNessuna valutazione finora

- Report On Sigmund FreudDocumento3 pagineReport On Sigmund FreudKenethhhNessuna valutazione finora

- Totem and Taboo (Barnes & Noble Library of Essential Reading): Resemblances between the Psychic LIves of Savages and NeuroticsDa EverandTotem and Taboo (Barnes & Noble Library of Essential Reading): Resemblances between the Psychic LIves of Savages and NeuroticsValutazione: 3 su 5 stelle3/5 (3)

- Freud and LiteratureDocumento3 pagineFreud and LiteratureAntonis DomprisNessuna valutazione finora

- D. F. Verene - Vico and FreudDocumento7 pagineD. F. Verene - Vico and FreudHans CastorpNessuna valutazione finora

- Sigmund Freud - Quotes Collection: Biography, Achievements And Life LessonsDa EverandSigmund Freud - Quotes Collection: Biography, Achievements And Life LessonsNessuna valutazione finora

- Sigmund Freud - Institute of PsychoanalysisDocumento3 pagineSigmund Freud - Institute of PsychoanalysisozuluokeoluchukwuNessuna valutazione finora

- Totem and Taboo (Barnes & Noble Digital Library): Resemblances between the Psychic Lives of Savages and NeuroticsDa EverandTotem and Taboo (Barnes & Noble Digital Library): Resemblances between the Psychic Lives of Savages and NeuroticsNessuna valutazione finora

- Freud On AmbiguityDocumento26 pagineFreud On AmbiguityJuan David Millán MendozaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Introduction of Sigmund FreudDocumento7 pagineThe Introduction of Sigmund FreudDarwin Monticer ButanilanNessuna valutazione finora

- Psychoanalysis of MythDocumento31 paginePsychoanalysis of Myththalesmms100% (3)

- Contents PageDocumento14 pagineContents PageWalees FatimaNessuna valutazione finora

- Daguplo - Uts Task 2 (Philosophers)Documento7 pagineDaguplo - Uts Task 2 (Philosophers)Carl GomezNessuna valutazione finora

- What Is Psychoanalytic CriticismDocumento13 pagineWhat Is Psychoanalytic CriticismJoseph HongNessuna valutazione finora

- Ahmad FardidDocumento4 pagineAhmad FardidHəsən RəhimliNessuna valutazione finora

- See More AboutDocumento5 pagineSee More AboutEmiel Pasco MijaresNessuna valutazione finora

- Sigmund Freud Male Sexual DisfunctionsDocumento8 pagineSigmund Freud Male Sexual DisfunctionsAna Carol MoszkowiczNessuna valutazione finora

- Psychoanalysis PDFDocumento6 paginePsychoanalysis PDFscrappyvNessuna valutazione finora

- American Psychoanalysis TodayDocumento29 pagineAmerican Psychoanalysis TodayMateus CedrazNessuna valutazione finora

- Adam Phillips Becoming Freud IntroDocumento12 pagineAdam Phillips Becoming Freud IntroedifyingNessuna valutazione finora

- Sigmund Freud: Navigation Search Freud (Disambiguation)Documento19 pagineSigmund Freud: Navigation Search Freud (Disambiguation)sanda3k100% (1)

- A Critical Appraisal of Freuds Ideas On PDFDocumento29 pagineA Critical Appraisal of Freuds Ideas On PDFMuhaimin Abdu AzizNessuna valutazione finora

- Freud and RyleDocumento44 pagineFreud and Rylerustie espiritu100% (1)

- Chapter IIIDocumento25 pagineChapter IIIDragu IrinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Sigmund FreuddDocumento14 pagineSigmund FreuddJoeyjr LoricaNessuna valutazione finora

- Sigmund FreudDocumento39 pagineSigmund FreudHanis RazakNessuna valutazione finora

- The Oceanic Feeling and A Sea ChangeDocumento15 pagineThe Oceanic Feeling and A Sea ChangeYajat BhargavNessuna valutazione finora

- Sigmund Freud TheoryDocumento5 pagineSigmund Freud Theorykarthikeyan100% (1)

- English 10Documento25 pagineEnglish 10Christian James MarianoNessuna valutazione finora

- Symptom or Inspiration H. D. Freud and T PDFDocumento16 pagineSymptom or Inspiration H. D. Freud and T PDFNikos Dimitrios MamalosNessuna valutazione finora

- Abraham MaslowDocumento14 pagineAbraham Maslowdusty kawiNessuna valutazione finora

- VIGOTSKY Prologo Mas Alla Del Principio de PlacerDocumento9 pagineVIGOTSKY Prologo Mas Alla Del Principio de PlacerPelículasVeladasNessuna valutazione finora

- Freud Essay SummaryDocumento2 pagineFreud Essay SummaryFile StorageNessuna valutazione finora

- Freuds Philosophical Inheritance PDFDocumento37 pagineFreuds Philosophical Inheritance PDFDaniel Lee Eisenberg Jacobs100% (1)

- What Is Psychoanalytic CriticismDocumento6 pagineWhat Is Psychoanalytic CriticismwprimadhiniNessuna valutazione finora

- Glossary of English To Pakistani TermsDocumento5 pagineGlossary of English To Pakistani TermsWaqas MurtazaNessuna valutazione finora

- Urban Gardening Fact Sheet PDFDocumento12 pagineUrban Gardening Fact Sheet PDFWaqas MurtazaNessuna valutazione finora

- Book Tohjeehat 1 by Raees Amrohi: Tawajoo Kia HaiDocumento3 pagineBook Tohjeehat 1 by Raees Amrohi: Tawajoo Kia HaiWaqas MurtazaNessuna valutazione finora

- Aqaid QuizDocumento49 pagineAqaid QuizWaqas MurtazaNessuna valutazione finora

- Week 3.2 Transcript The Imperfect (Mudhari) VerbDocumento14 pagineWeek 3.2 Transcript The Imperfect (Mudhari) VerbWaqas MurtazaNessuna valutazione finora

- Links - Books of Jamia Tul Madina Online: Kitab Ul AqaidDocumento1 paginaLinks - Books of Jamia Tul Madina Online: Kitab Ul AqaidWaqas MurtazaNessuna valutazione finora

- Its in The Way That You Use ItDocumento3 pagineIts in The Way That You Use ItWaqas MurtazaNessuna valutazione finora

- Leica Rugby 320 410 420 BRO En-1Documento6 pagineLeica Rugby 320 410 420 BRO En-1luigiabeNessuna valutazione finora

- Evaluation of Global Research Trends in The Area of Food Waste D - 2020 - Food CDocumento10 pagineEvaluation of Global Research Trends in The Area of Food Waste D - 2020 - Food CAliNessuna valutazione finora

- Astrophysics & CosmologyDocumento2 pagineAstrophysics & CosmologyMarkus von BergenNessuna valutazione finora

- Eureka Forbes ReportDocumento75 pagineEureka Forbes ReportUjjval Jain0% (1)

- Chapter 4 TurbineDocumento56 pagineChapter 4 TurbineHabtamu Tkubet EbuyNessuna valutazione finora

- Union Fork & Hoe No. 19Documento68 pagineUnion Fork & Hoe No. 19Jay SNessuna valutazione finora

- Instant Download Professional Nursing Practice Concepts Perspectives 7th Blais Hayes Test Bank PDF ScribdDocumento32 pagineInstant Download Professional Nursing Practice Concepts Perspectives 7th Blais Hayes Test Bank PDF ScribdDanielle Searfoss100% (10)

- Facility Systems, Ground Support Systems, and Ground Support EquipmentDocumento97 pagineFacility Systems, Ground Support Systems, and Ground Support EquipmentSree288Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ryan's DilemmaDocumento11 pagineRyan's DilemmaAkhi RajNessuna valutazione finora

- B.W.G. - Birmingham Wire Gauge: The Wall Thickness of Pipes - Gauge and Decimal Parts of An InchDocumento3 pagineB.W.G. - Birmingham Wire Gauge: The Wall Thickness of Pipes - Gauge and Decimal Parts of An InchLuis Fernando Perez LaraNessuna valutazione finora

- DHL Product Solutions Portfolio 2017Documento1 paginaDHL Product Solutions Portfolio 2017Hanzla TariqNessuna valutazione finora

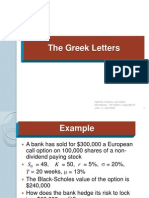

- The Greek LettersDocumento18 pagineThe Greek LettersSupreet GuptaNessuna valutazione finora

- Graviola1 Triamazon, AntiCancer, InglesDocumento2 pagineGraviola1 Triamazon, AntiCancer, InglesManuel SierraNessuna valutazione finora

- Toolbox Talks Working at Elevations English 1Documento1 paginaToolbox Talks Working at Elevations English 1AshpakNessuna valutazione finora

- Dead Zone I Air AgeDocumento7 pagineDead Zone I Air AgeJaponec PicturesNessuna valutazione finora

- LC Magna Leaflet 2019Documento2 pagineLC Magna Leaflet 2019saemiNessuna valutazione finora

- 8Documento3 pagine8Anirban Dasgupta100% (1)

- Lesson 2 Arts of East AsiaDocumento21 pagineLesson 2 Arts of East Asiarenaldo ocampoNessuna valutazione finora

- HellforgedDocumento89 pagineHellforgedBrian Rae100% (1)

- AE451 Aerospace Engineering Design: Team HDocumento140 pagineAE451 Aerospace Engineering Design: Team HÖmer Uğur ZayıfoğluNessuna valutazione finora

- China Care Foundation - Fall 2010 NewsletterDocumento8 pagineChina Care Foundation - Fall 2010 NewsletterChinaCareNessuna valutazione finora

- Correlation of Body Mass Index With Endometrial Histopathology in Abnormal Uterine BleedingDocumento101 pagineCorrelation of Body Mass Index With Endometrial Histopathology in Abnormal Uterine BleedingpritamNessuna valutazione finora

- Kia September 2020 Price List: Picanto ProceedDocumento2 pagineKia September 2020 Price List: Picanto ProceedCaminito MallorcaNessuna valutazione finora