Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

CALL Vocabulary Learning in Japanese: Does Romaji Help Beginners Learn More Words?

Caricato da

minhDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

CALL Vocabulary Learning in Japanese: Does Romaji Help Beginners Learn More Words?

Caricato da

minhCopyright:

Formati disponibili

355

Yoshiko Okuyama

CALL Vocabulary Learning in Japanese:

Does Romaji Help Beginners

Learn More Words?

YOSHIKO OKUYAMA

University of Hawaii at Hilo

ABSTRACT

This study investigated the effects of using Romanized spellings on beginnerlevel Japanese vocabulary learning. Sixty-one rst-semester students at two universities in Arizona were both taught and tested on 40 Japanese content words in

a computer-assisted language learning (CALL) program. The primary goal of the

study was to examine whether the use of RomajiRoman alphabetic spellings

of Japanesefacilitates Japanese beginners learning of the L2 vocabulary. The

study also investigated whether certain CALL strategies positively correlate with

a greater gain in L2 vocabulary. Vocabulary items were presented to students in

both experimental and control groups. The items included Hiragana spellings,

colored illustrations for meaning, and audio recordings for pronunciation. Only

the experimental group was given the extra assistance of Romaji. The scores

of the vocabulary pretests and posttests, the types of online learning strategies

and questionnaire responses were collected for statistical analyses. The results

of the project indicated that the use of Romaji did not facilitate the beginners

L2 vocabulary intake. However, the more intensive use of audio recordings was

found to be strongly related to a higher number of words recalled, regardless of

the presence or absence of Romaji.

KEYWORDS

CALL, Vocabulary Learning, Japanese as a Foreign Language (JFL), Romaji Script, CALL

Strategies

INTRODUCTION

Learning a second language (L2) requires the acquisition of its lexicon. How do

American college students learn basic L2 vocabulary in a CALL program? If the

vocabulary is written in a nonalphabetic L2 script, such as Japanese, is it more

efcient to learn the words with the assistance of more familiar Roman-alphabetic

symbols? This experimental study explored these questions in the context of Japanese CALL vocabulary learning.

CALICO Journal, 24 (2), p-p 355-379.

2007 CALICO Journal

356

CALICO Journal, Vol. 24, No. 2

Teachers of less commonly taught languages (LCTLs) are faced with a variety

of issues that include lack of pedagogically sound resources and instructional materials (Johnston & Janus, 2003). Although categorically an LCTL, Japanese is in

fact the most commonly taught Asian language in the United States. A great challenge awaits learners of this nonalphabetic language, however, because Japanese

is ranked as category 4 language (highest) by the US Federal standards in terms

of its difculty for American students to acquire. While more college-level course

books are being published and software programs being created, many aspects of

teaching and learning Japanese still remain to be empirically investigated. One of

these underresearched aspects is the effect of nonalphabetic script on word learning.

Japanese Orthography

Japanese consists of three types of script: Hiragana, Katakana, and Kanji. The rst

two are called syllabaries because each symbol is a syllabic unit, while Kanji

characters are ideographic symbols. Japanese children have to memorize the two

syllabaries, with each set made of the basic 46 syllabic units and 61 extensions,

before mastering over 2,000 Kanji characters in order to master all three sets

of Japanese script. This is no easy task for learners since the difculty with the

syllabaries only worsens when learners come to understand that not all symbols

clearly map onto the sound units of the Japanese language (e.g., the same sound

e in oneesan big sister and eego English happens to be transcribed with different hiragana symbols).

Yet, the perceived difculty in learning Kana might be relative. According to

the orthographic depth hypothesis (Katz & Frost, 1992), it is easier to learn to read

words written in a transparent script than an opaque script. Kana syllabaries are

considered a transparent script, a type of orthography in which phoneme-grapheme mappings are highly consistent, and these symbols are processed differently

than Kanji characters by native speakers of Japanese (Ellis et al., 2004; Kawakami, Hatta, & Kogure, 2001; Sumiyoshi et al., 2004). English, on the other hand, is

called an opaque script, a type of orthography that lacks systematic sound-symbol

correspondence. In English, many alphabetic letters are associated with several

different sounds (particularly in the case of its ve vowels), making the mapping

of the letters to the sounds less predictable. Thus, unlike the English alphabet or

Kanji characters, the regularity of the symbol-sound mappings makes hiragana

an exceptionally transparent orthography (Ellis et al., 2004, p. 443).

Romaji versus Japanese Script

According to the Standards for Japanese Language Learning (National Standards in Foreign Language Education Project, 1999), there is an orthographic barrier between English and Japanese: In order to be able to read Japanese materials

written for adult native speakers, students must learn two different syllabic writing

systems and approximately 2,000 Chinese characters (kanji), most of which have

multiple meanings and readings (p. 332). The complexity of the Japanese writing

Yoshiko Okuyama

357

system poses a great challenge to learners of Japanese as a foreign language (JFL)

especially at the beginning level. In the US, Romaji (i.e., Romanized spellings of

Japanese text) is commonly used as a starter for JFL beginners.

Romaji is not entirely foreign to native speakers of Japanese. The script is used

on limited occasions by Japanese native speakers, such as writing their name on

a passport or indicating the name of a train station to foreign visitors. However,

it is not an integral part of the native orthography and is not mixed with the other

scripts within the same text. Romaji does not always transcribe the spoken language in a perfect grapheme-phoneme match. Moreover, both the Hepburn system (a style of Romanization invented by a missionary in 1867) and Kunrei-shiki

(a Romanization system adopted by the Japanese government in 1937) have been

used in Japan (Hannas, 1997). Two varying ways to transcribe some sounds (e.g.,

/fu/ vs. /hu/, /zi/ vs. /ji/) cause confusion on the part of readers and writers. Contrary to Romaji, grapheme-to-phoneme correspondences are entirely regular in

Hanyu Pinyin (meaning assembling sound), a phonetic alphabet set of 26 Roman letters in 13 letter groups used in addition to the traditional character system

in China (Chen, Fu, Iversen, Smith, & Matthews, 2002, pp.1089-1091). Pinyin is

taught to school age children in China as a phonetic assistance in learning a set of

about 6,000 meaning-based characters. Like Romaji, however, Pinyin is not used

as an independent written script nor mixed with the Chinese characters. Thus, it is

much easier for (adult) native speakers of Japanese and Chinese to process texts

entirely in the traditional orthography rather than in Romaji or Pinyin.

Many textbooks for JFL learners published in the US seem to encourage the use

of Romaji as an effective pedagogical aid. Books designed for self-study, such as

Japanese in 10 Minutes a Day (Kershul, 1992) and Master the Basics: Japanese

(Akiyama & Akiyama, 1995), are also written entirely in Romaji. An audiotapebased program, Just Listen n Learn Japanese (Katao & Takada, 1994), is accompanied with a transcription of the recordings written only in Romaji. By contrast,

college-level textbooks for JFL beginners, such as Yookoso (Tohsaku, 1994) and

Nakama (Makino, Y. Hatasa, & K. Hatasa, 1998), are mainly written in authentic

Japanese orthography.

When it comes to CALL software, existing programs lack consistency in spelling Japanese materials. CALL tutorials and commercially available language software vary in the degree of their use of Romaji as opposed to authentic Japanese

orthography. For example, NihongoWare 1 presents vocabulary and conversational materials exclusively in Romaji, while TriplePlay Plus! Japanese has these

items only in Japanese script. Yet, some programs, such as Robo-Sensei (Nagata,

2004), come in two versionsRomaji only and Japanese script onlyfor the user

to choose from.

In the North American context, Romaji is assumed to be an effective learning

aid particularly during the initial period of JFL learning. However, when to switch

to the authentic script has been controversial among JFL practitioners (Dewey,

2004; Hatasa, 2002). Those who advocate the early introduction of kana and kanji

have pedagogical philosophies quite different from those of the proponents of

delayed introduction. Divided views on the use of Romaji also exist among JFL

358

CALICO Journal, Vol. 24, No. 2

learners. Even if the kana syllabaries are taught in the early stages of instruction,

as in most JFL classes, many students are likely to use Romaji as a quick and easy

note-taking device throughout the rst year. These students claim that the use of

Romaji reduces their language-related anxiety and helps them overcome the challenge of learning Japanese especially when their L1 is English, a Roman alphabetic language. They may adamantly defend their Romaji transcription as a way

to absorb a large amount of new words efciently for quizzes and exams. Others

may simply consider this assistive device as a crutch, inhibiting themselves from

developing strong reading and writing skills in Japanese. Moreover, JFL learners

views on Romaji may also be inuenced by their teachers attitudes toward the

script (Dewey, 2004).

The question is: does the use of Romaji really facilitate JFL beginners language learning? Little research has been done to test whether substituting Japanese

orthography for Romaji in introductory textbooks or CALL programs is indeed

an effective pedagogical tool. In the absence of empirical evidence for the value

of Romaji, teachers are left to select courseware or textbooks for beginning-level

students based on their experience as an L2 learner or their own instincts. The

primary goal of this study is, therefore, to nd empirical evidence to address the

question of the pedagogical value of Romaji in CALL for JFL beginners.

L2 Vocabulary Learning across Different Nonalphabetic Orthographies

The main issue of second language acquisition discussed in this study is collegelevel students L2 word learning in a nonalphabetic language. L2 vocabulary gain

plays a crucial role especially in beginning SLA (Ellis, 1995). Although the topic

of vocabulary is no longer undervalued in SLA research due to a rapid increase

in L2 vocabulary research, little is available regarding how L2 learners process,

store, and retrieve words written in nonalphabetic script. Because research on L2

word recognition skills tends to be conducted on the learners of alphabetic languages, some issues specic to the lexical acquisition of nonalphabetic languages

are yet to be investigated.

As mentioned above, a major challenge to the beginners in Japanese is to learn

new vocabulary in the orthographically different script. In fact, for L2 learners of

any nonalphabetic language, the orthographic form is one key element affecting

lexical learning: The form of items is more likely to inuence difculty than

meaning, because there is much more shared knowledge of meaning between two

distinct languages than there is shared form (Nation, 2001, p. 29). Learning new

words by itself is a complex process and requires learners to access the semantic representation of the new word while simultaneously making sound-spelling

correspondence. Naturally, the process becomes even more demanding if the L2

script is completely different from that of L1. For learners whose rst language

is not related to the second language, the learning burden will be heavy (Nation,

2001, p. 24) because the learning burden of the written form of words will be

strongly affected by rst and second language parallels (p. 45). L2 orthography

also plays a signicant role even beyond word recognition. L2 learners acquisi-

Yoshiko Okuyama

359

tion of reading skills is dependent upon their ability to identify the printed (i.e.,

orthographic) form of a word or lexical item in order to activate the words meaning, structural/syntactic information, and other pragmatic or world knowledge associations (Fender, 2003, p. 291).

The orthographic distance between L1 and L2 creates a cognitive overload in

deciphering L2 lexical items or processing L2 reading materials (Akamatsu, 1999;

Fender, 2003; Laufer, 1997; Koda, 1997, Tan et al., 2003), whereas the similarity in L1 and L2 spelling patterns facilitates word recognition (Muljani, Koda, &

Moates, 1998). The orthographic mismatch may make L2 word learning challenging for beginners but not impossible. For example, Wong, Perfetti, and Liu (2003)

found that native speakers of English were able to develop sensitivity toward

structural complexity and compositional relationship of Chinese radicals at the

early stage of L2 learning. According to their lexical processing model of Chinese

characters, understanding Chinese characters involves three interlinked constituents: orthographic, phonological, and semantic. Since one-to-one grapheme-phoneme mappings are unavailable in the logographic script of Chinese, L2 learners

visual-orthographic processing turned out to be the most critical element. In this

model, learners of Chinese must rst work on stroke analysis, seeking information in the orthographic unit of the character, and then access the phonological

unit of the character as well as its semantic unit. Yet, rst-year learners of Chinese

have not made a strong connection between the orthographical and phonological

units. Chung (2002, 2003) also looked at alphabetic learners of Chinese, shedding

light on how to reduce cognitive overload derived from L1-L2 script discrepancy.

When it comes to alphabetic learners of Japanese, research has been done primarily on American students processing of Kanji characters (e.g., Matsunaga, 1995,

2001) rather than Kana.

As mentioned before, Japanese syllabaries and kanji characters require different types of processing. Therefore, drawing directly on the ndings of research

in logographic script does not sufce in understanding how L2 learners process

and store words written in syllabic script. The current study lls a critical need by

investigating whether Romaji, a phonetic assistance consisting of visually familiar Roman alphabet letters, helps JFL beginners overcome the burden of learning

words in Hiragana, a nonalphabetic orthography.

CALL Strategies

This study also investigated what strategies students were likely to use when

learning L2 words in multimedia software. Gathering useful information on learners strategies has always been a challenge to researchers. Survey studies on vocabulary learning strategies (e.g., Kudo, 1999) provide an insightful account on

learners self-reported strategy use, but there is often a discrepancy between what

strategies L2 learners report having used and what they actually used in languagelearning problem solving. To obtain a holistic view of L2 learner behaviors, we

need to incorporate a method of recording the students actual strategy use.

Here, CALL research technologies come in handy: the computer can be pro-

360

CALICO Journal, Vol. 24, No. 2

grammed to compile inventories of behavioral patterns followed by users of language software. The use of hypermedia presents intensive interaction between

user and computer and executes a variety of tasks, allowing for a rich recording

of online learning strategies in an unobtrusive way. Recently, there has been a

surge of interest in CALL strategies and CALL user tracking technologies (AlSeghayer, 2001; Ashworth, 1996; Collentine, 2000; Hwu, 2003; Hegelheimer &

Tower, 2004; Laufer & Hill, 2000; Liou, 2000; Vincent & Hah, 1996).

For example, Ashworths (1996) CALL program, The Observer, was designed

to store L2 learners keyboard activities (e.g., mouse-clicks and cursor movements) in computer les. He suggested the possibility of observing other online

actions, such as transcriptions of user input in computer-mediated conversational

exchanges or frequency counts of accessing online dictionaries and thesauruses

in a reading comprehension task. Liou (2000) also emphasized the advantage

of using computers recording abilities to collect learner data. Hwu (2003) used

WebCTs student-tracking system to collect learner data during CALL activities.

Other SLA studies have also incorporated user behavior tracking technologies as

a data collection methodology or have documented strategies employed by CALL

users for L2 word learning (Collentine, 2000; Laufer & Hill, 2000; Al-Seghayer,

2001), showing great promise for conducting L2 vocabulary research in this electronic medium.

CALL is thought to have great potential in increasing the amount of L2 input

and improving the relatively low L2 achievement by learners of Asian languages

(McMeniman, 1997). Although Chinese, Japanese, Hebrew and other nonalphabetic LCTLs have traditionally suffered from a shortage of orthographically well

designed CALL programs due to problems in displaying ideographs or rightto-left writing (Ariew, 1991, p. 34), the development of Unicode has improved

CALL programs capability of handling foreign fonts (Corda & Van Der Stel,

2004). However, it is still unknown how efciently CALL can assist learners of

non-Western, nonalphabetic languages. For instance, what sort of CALL strategies do JFL students use in a self-paced computer environment? What CALL

strategies facilitate the learning of this orthographically complex difcult language, especially with respect to trying to absorb as many new words as possible?

The current study attempts to demonstrate the feasibility of applying computer

technology to document CALL strategies employed in learning nonalphabetic

vocabulary materials. The ndings from the study will also add insight on the

relationship between L2 script and vocabulary learning in a CALL environment,

providing useful implications to JFL teachers as well as software developers.

METHODOLOGY

The main purpose of the study was to investigate the effects of using Romaji on

English-speaking college students learning of beginning-level Japanese words.

The research question was whether or not the availability of Romaji signicantly

facilitated learners short-term learning of such words when using a CALL program.

Yoshiko Okuyama

361

The primary independent variable of the study was the type of orthography used

to present the Japanese vocabulary items (i.e., Japanese vocabulary instruction in

Hiragana only or together with Romaji). The dependent variable was L2 learners

immediate vocabulary increase in Japanese, measured by both kana and sound

recognition tests in the same CALL environment. Because the research purported

to test the impact of the independent variable (i.e., script type) on the dependent

variable (i.e., L2 vocabulary learning), an experimental design was selected. The

students in the control group learned new words in a Hiragana-only version of

the CALL program, while the students in the experimental group learned the same

words in a Romaji-plus version of the program. It was hypothesized that the use

of Romaji would result in better attainment of the newly learned nonalphabetic

(Japanese) words by English-speaking students.

Subjects

The target population for this experiment was dened as English-speaking learners of entry level Japanese who were enrolled in American universities. A sample

of students from rst-semester Japanese courses was thought to be representative

of the identied population.

Sixty-one students of rst-semester Japanese in two research universities were

randomly assigned to either the experimental or control group. The control group

(n = 31) was made of 18 students from Arizona State University (ASU) and 13

students from Northern Arizona University (NAU), while the experimental group

(n = 30) consisted of 17 students from ASU and 13 students from NAU. The average age of the students was 21.7 years. Although there was a gap in the mean ages

of the students at the two universities (M = 20.8 for ASU; M = 23.0 for NAU),

an unpaired t test showed that the discrepancy in age distribution was not statistically signicant when the alpha level was set at .01: t (59) = -2.101, p = .0399.

A frequency distribution of each of the other demographic characteristics was

also made between the groups by university. There were more male students (23

in ASU, 16 in NAU) than female students (12 in ASU, 10 in NAU). More than

half of each group (n = 20 for both groups) had no experience with the Japanese

language prior to the semester. Sixteen ASU students identied themselves as

uent in a language other than English, while only 6 NAU students identied

themselves as uent in another language. However, Each group had the same

number (n = 5) of international students (i.e., nonnative speakers of English). The

demographic comparisons of the two school groups indicated that, whereas NAU

students were relatively older, ASU students had slightly more linguistically enriched backgrounds. Despite these few differences, the overall background characteristics of ASU and NAU students were similar. Thus, it was appropriate to

treat the two school groups as one and to draw conclusions about the population.

The students at both institutions used the same textbook, Yookoso! in their

classes.1 Having little or no previous knowledge of Japanese, the students at both

ASU and NAU were introduced to the hiragana and katakana syllabaries in class

within the rst few weeks of the semester. They were instructed to use the vo-

362

CALICO Journal, Vol. 24, No. 2

cabulary CALL program to learn new Japanese words (i.e., words other than those

presented in the textbook) as a supplemental learning task.

Pilot Phase of the Project

Early prototypes of the CALL program were piloted for feasibility and effectiveness in a series of sessions with 20 volunteer subjects. Feedback from the volunteer subjects enabled the researcher to address problematic areas and strengthen

the programs design and functionality, including the use of English translations

to reinforce learners accurate interpretation of visual and audio input and the addition of situational contexts (e.g., dialogues) to enrich the vocabulary learning.

Hardware and Software

The instructional materials used in the vocabulary CALL program were an adaptation of a commercially available CD-ROM software program, Learn to Speak

Japanese (1994), a self-paced language program for beginning-level learners of

Japanese. Four of 20 lessons in Learn to Speak Japanese, four lessons were selected and adapted for this study.2 The existing words of the four lessons and their

accompanying illustrations and audio recordings were entirely replaced with new

words and color drawings as well as new recordings by two different Japanese

speakers (a male and a female). The modied lesson materials contained a total

of 40 words that were not included in the rst-semester Japanese class (for more

information, see the Tasks section below).

The CALL program, designed for Macintosh,3 consisted of three modules: (a) a

preview module on how to use the CALL program, (b) a lesson module containing the exercises, and (c) a testing module to administer tests on vocabulary recall.

It is important to emphasize that the lesson module was designed not only to

provide L2 vocabulary lessons to the students, but also to gather learner data on

each student (i.e., data on online learning behaviors such as how long the student

spent on each lesson). Similarly, the testing module was programmed to execute

the test batteries and then to record an individual students test scores and other

information (e.g., reaction time to test items).

The method of computer-mediated data collection was chosen because of its

ability to discretely and objectively capture language-learning data and languagetesting data and to reduce internal threats to validity such as teacher experience

during the learning session (Chapelle and Jamieson, 1991). Specically, in this

study, the program randomized the test items in the testing module. Students were

tested on the same words but in different orders, thereby greatly reducing subject sensitivity toward individual items that could have developed in the lesson

module. This method also randomly distributed words of varying difculty (e.g.,

word length ranging from two-syllable to ve-syllable words) throughout the test.

Thus, computer technology helped not only to control the effect of extraneous

variables but also to secure accuracy and consistency in measurement. The study

was able to pool a large amount of data without data collection errors.

363

Yoshiko Okuyama

Tasks

The aim of instruction in this experiment was to expose the students to 40 Japanese lexical items in two versions of a CALL program (with Romaji and without

Romaji) in order to test which version can teach L2 vocabulary lessons more

effectively. All the words were concrete nouns in Japanese and were of appropriate length and complexity for the students prociency level. Words containing

consonant-glide combinations (i.e., hiragana syllables such as kya, hyi, ryo) and

geminates (i.e., double consonants as in sakka) were avoided except for one item

(sentakki refrigerator). The selected words were relatively high frequency words,

and the range of the number of syllables varied from two to ve. All words were

hiragana type words that t each lessons vocabulary theme and which had clear

English equivalents. Because the students lived in Arizona, familiar creatures of

desert life (e.g., scorpion and hummingbird) were also included. The Japanese

instructors at each school were also consulted on the nal corpus of vocabulary

items in order to eliminate any words of potential familiarity to the students. For

preliminary vocabulary assessment, 10 words were drawn randomly from the 40

for each of two pretests. All 40 words used in the lessons and the tests are listed

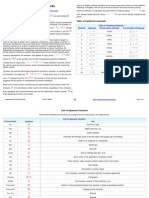

in Table 1.

Table 1

List of Japanese Vocabulary Items

Lesson 1 Structural Emphasis: Likes and dislikes

( )

1. shika deer

Vocabulary theme:

Desert animals

2. hebi snake

3. tokage lizard

4. uzura quail

5. sasori scorpion

6. yamaneko wildcat

7. koomori bat

8. fukuroo owl

9. hachidori hummingbird

10. araiguma raccoon

Lesson 2 Structural emphasis: Describing things

(... // )

1. shima island

2. taki waterfall

3. umi sea

4. mori forest

5. kazan volcano

Average word length:

3.4 syllables

Vocabulary theme:

The physical world/the cosmos

364

CALICO Journal, Vol. 24, No. 2

6. kasee Mars

7. dosee Saturn

8. taiyoo Sun

9. sekidoo equator

10. nagareboshi shooting

star

Lesson 3 Structural emphasis: This and that

(// )

1. masu trout

Average word length:

3.0 syllables

Vocabulary theme:

Ocean life

2. kani crab

3. kai seashell

4. same shark

5. kame turtle

6. hitode starsh

7. kujira whale

8. unagi eel

9. kamome seagull

10. tobiuo ying sh

Lesson 4 Structural emphasis: Where is it?

( )

1. hasami scissors

Average word length:

2.6 syllables

Vocabulary theme:

Household items

2. kabin vase

3. kagami mirror

4. denchi battery

5. soojiki vacuum cleaner

6. dentaku calculator

7. gomibako trash can

8. fuutoo envelope

9. reezooko refrigerator

10. sentakuki washing

machine

Average word length:

3.8 syllables

Each word was presented with a color drawing and an English translation. The

use of the English gloss was necessary to ensure the clarity of meaning of the L2

word, which may not always be immediately evident in a drawing alone. There

were also buttons for the pronunciation of a single word and for a conversation

containing the relevant vocabulary item. The audio recordings of single-word

pronunciations as well as dialogues were made in a male voice for some and in

365

Yoshiko Okuyama

a female voice for others. Both speakers were native speakers of standard Tokyo Japanese. Each dialogue was a dyadic conversation scripted to present the

keyword in a sentence structure familiar to the rst-semester Japanese learners.

For example, in lessons 1 and 2, Speaker A asked a yes/no question (e.g., X wa

suki desuka? Do you like X? or X wa tooi desuka? Is X far away?), to which

Speaker B responded positively or negatively. In lessons 3 and 4, Speaker A asked

an interrogative question (e.g., Sore wa nan desuka? What is that? or X wa doko

desuka? Where is X?) to which Speaker B supplied pertinent answers. These

sentence structures were also in accordance with the grammar instruction that

both the ASU and NAU students had already been provided in their regular classroom lessons. The spellings of the vocabulary and dialogues were presented in

Hiragana because of the students prociency level. The Romaji spellings of the

40 words (not the dialogues) were included in the version of the CALL program

used by the students in the experimental group. Figure 1 shows the structure of the

vocabulary displays in the lesson module.

Figure 1

Vocabulary Display in the Lesson Module

Button

to hear dialogue

and see its

written script

Button

to review

hiragana

syllabary

Button

for grammar

explanation

Drawing with

button for

single-word

pronunciation

Navigation buttons

In the lesson module, the following types of information were collected: (a) total learning time (i.e., the time the subject spent per lesson and on all the lessons),

(b) audio access (i.e., the number of clicks made on the drawing to hear the Japanese pronunciation of the word), (c) kana access (i.e., the number of clicks made

on Kana to review the syllabary of the 46 basic hiragana symbols and to learn

some tips on how to read sets of symbols as words), (d) grammar access (i.e., the

number of clicks made on grammar button to access grammatical explanation),

and (e) dialogue access (i.e., the number of clicks made on dialogue button to hear

the dialogue and have it displayed in Japanese text).

366

CALICO Journal, Vol. 24, No. 2

The testing module was made up of two posttests. The purpose of the posttests

was to measure students short-term vocabulary learning. The immediate recall

of the instructed L2 vocabulary was evaluated in terms of L2 sound recognition

and of L2 script recognition. The rst posttest, Sound Games, consisted of four

pages of sound recognitions on all the 40 words and measured students ability to

identify the illustration (for meaning) that corresponded to an L2 sound cue. The

second posttest, Kana Games, presented four pages of kana script recognition

test on the same 40 words and assessed students ability to select the correct illustration based on the hiragana spelling shown in the upper left-hand corner of

the display (see Figure 2). All the test directions were written in English.

Figure 2

Sample Kana Game

In the testing module, the program collected learner information (e.g., subjects

name, response items, and score of each vocabulary test automatically calculated

by the computer) and stored the data in the individual subject le.

Procedures

The students were rst given two pen-and-paper pretests, each of which contained

10 Japanese words. The rst pretest was a sound recognition test, and the second

pretest was a written hiragana recognition test. The pretests were administered to

ensure that there was no signicant difference in Japanese vocabulary knowledge

between the experimental and control groups as well as between the two university groups. After a brief orientation session in which the features of the program

were presented and explained, the students started the vocabulary lessons at their

own computer stations. They were told that the main instructional objective was

to learn new Japanese words using the multimedia software. They were allowed

to navigate from one lesson to another at their own pace. After completing all

of the lesson modules, the students took the posttest in the testing module. The

367

Yoshiko Okuyama

students completed both the lessons and tests in one sitting at the laboratory. After

exiting the program, the students were asked to ll out a short questionnaire as the

last procedure. The main purpose of the exit questionnaire was to collect various

information on the learners. The rst portion of the questionnaire was designed

to obtain subject characteristics (e.g., gender, age, major, native language, prior

exposure to Japanese and length of experience in learning Japanese, and prior

foreign language learning experience). Questions related to the students demographic background were adapted from Graces (1995) CALL experimental study

on L2 learners of French. Other parts were drawn from a study of JFL learners by

Okamura (1995) for comparative purposes.

RESULTS

Group Differences

The results of the analysis of the subject characteristics from the questionnaire

showed that both gender and age were evenly distributed between the groups and

the universities. The only substantial difference was the amount of previous Japanese exposure. In the control group (n = 31), 25 students had had some experience

learning Japanese (e.g., as a language course requirement in high school) prior to

taking the rst-semester Japanese course in college. In the experimental group (n

= 30), only half of the students had had some prior exposure to the language.

However, in spite of the discrepancy in their previous Japanese experience, the

groups did not differ in their knowledge of the Japanese vocabulary items. The results from a t test conrmed that the group-based difference in pretest scores was

not statistically signicant at the .01 level. Table 2 shows the means and standard

deviations of the pretest scores by group and pretest type.

Table 2

Means and Standard Deviations of Pretest Scores by Pretest Type and by Group

Pretest

Prestest 1

Pretest 2

Group

SD

Cont (n = 31)

1.000

1.033

Cont (n = 31)

1.613

1.407

Exp (n = 30)

Exp (n = 30)

1.233

1.067

1.223

1.015

The very low scores in both pretests indicate that the students knowledge of

Japanese words was minimal prior to the CALL instruction and was evenly spread

across the groups.

Overall L2 CAL-based Vocabulary Learning

Table 3 presents a summary of the pretest-posttest results for both groups combined.

368

CALICO Journal, Vol. 24, No. 2

Table 3

Means and Standard Deviations of Pretest and Posttest Scores for Combined

Groups by Test Type

Test

Prestest 1

Pretest 2

Posttest 1

Posttest 2

SD

1.115

1.127

21.262

9.588

1.344

18.738

1.250

11.275

While the mean scores of the pretests were very low, those of the posttests

indicate a sizable increase in the students vocabulary knowledge after the CALL

instruction: students correctly identied approximately half of the 40 items on

each posttest (21.3 [53%] in posttest 1 and 18.7 [47%] in posttest 2). This general

outcome provides evidence that students learned an appreciable amount of vocabulary as the result of using the CALL program.

Research Questions and Hypotheses

The main research question in this study was whether or not Romaji facilitated

Japanese beginners short-term learning of hiragana words in CALL. The primary

research hypothesis was

There is a systematic relationship between the presence or absence of Romaji

assistance and students gain in knowledge of Japanese vocabulary.

Romaji and Japanese Vocabulary Learning

To investigate the effect of Romaji, two-tailed independent t tests were performed

between the control and experimental groups on the two posttests. Generally

speaking, a one-tailed t test is more powerful. However, the two-tailed procedure

was used because both the possible positive and negative effects of Romaji on

vocabulary learning had to be considered. The results of the t tests did not show a

signicant difference in either posttest 1 or posttest 2 (t = .262, df = 59, p = .794

and t = .364, df = 59, p = .717, respectively).

Another variable measured was reaction time (RT) to the vocabulary items in

the posttest, here measured in computer ticks (60 ticks = 1 sec). The experimental groups mean RT was slightly lower than that of the control group, 183 ticks

versus 230 ticks, for posttest 1 and virtually the same for posttest 2. Independent

t tests did not show a signicant difference for either posttest.

CALL Strategies and Japanese Vocabulary Learning

As mentioned earlier, this study also examined the students use of several learning strategies. These strategies were labeled as CALL strategies because they

inform us of how students approached the L2 learning tasks in a CALL environ-

369

Yoshiko Okuyama

ment. The program recorded the students use of the CALL strategies in individual computer les. The following acronyms are used in reporting the analyses

of the use of these strategies:

1. TL = total learning time spent on the CALL program,

2. AA (Audio Access) = clicking the audio recording button for each new L2

word,

3. KA (Kana Access) = clicking the kana tutor button to review the hiragana

syllabary,

4. GA (Grammar Access) = clicking the Grammar Help button to learn about

the sentence structures used in the program, and

5. DA (Dialogue Access) = clicking the dialogue button to listen to a dyadic

conversation containing the target word.

Students use of each strategy (other than TL) was measured by the number of

clicks made on the relevant button. Table 4 presents descriptive statistics of students use of all CALL strategies.

Table 4

Means and Standard Deviations of Use of CALL Strategies

Strategy

SD

TL

1339.508

631.627

KA

1.918

4.961

AA

GA

DA

188.410

2.721

71.311

182.836

2.788

37.649

The unit of measure for TL was 1 sec; the average TL (1,340 in the table) is equal

to approximately 22 minutes. The standard deviation is very large (631.627), indicating a wide disparity in the length of time individual students spent in the

program. Among the other strategies, the mean score of AA was found to be the

highest (M = 188.410 clicks). The second most frequently used strategy was DA

(M = 71.311 clicks). The least used functions were KA (M = 1.918 clicks) and GA

(M = 2.721 clicks).

To examine whether the students in the experimental group studied the CALL

vocabulary differently than those in the control group, t tests were performed on

the use of the strategies. Table 5 displays the results of the t tests. There were no

signicant differences between the groups in the use of any of the strategies.

370

CALICO Journal, Vol. 24, No. 2

Table 5

Between-group Comparisons of the Use of CALL Strategies

Strategy

TL

Mean diff.

AA

KA

GA

DA

df

34.452

59

1.347

59

72.629

-0.680

-9.226

0.211

.833

1.062

.293

59

1.570

59

-0.951

59

-0.956

.122

.345

.343

To determine whether students use of CALL strategies were related to their

vocabulary learning, the control and experimental groups were combined and correlations between their use of strategies and posttest scores were computed (see

Table 6).

Table 6

Correlation Coefcients of Use of CALL Strategies and Posttest Scores

Posttest 1

Posttest 2

TL

.309

.285

AA

.499

.513

KA

-.079

-.143

GA

-.078

-.133

DA

.056

-.048

The gures in Table 6 show that using AA (sound) was highly correlated with

both posttests: .499 for Posttest 1 and .513 for Posttest 2. A stepwise regression

analysis conrmed that the frequent use of audio access was indeed a strong predictor of vocabulary learning.

To further investigate the extent to which this strategy alone contributed to vocabulary learning, a linear regression was run on AA and the two posttests. In

this analysis, AA was used as the predictor variable and the posttest scores as the

criterion variable. For posttest 1 (sound recognition), the coefcient of determination (r2) was .249, meaning that approximately 25% of the variance in posttest 1

was explained by the variance in AA (Audio Access). For posttest 2 (kana recognition), the coefcient of determination was .264, meaning that about 26% of the

variance in posttest 2 was explained by the variance in AA. Based on the results

this analysis, AA is a clearly important predictor of vocabulary learning.

To summarize this section, the results of statistical analyses in this study did

not provide empirical support for the benecial role of Romaji in learning new

hiragana words within a short instructional period. Instead, the results showed a

systematic relationship between the use of L2 audio and L2 vocabulary learning.

DISCUSSION

Effects of Romaji

It was hypothesized in this project that the use of Romaji would help Englishspeaking learners acquire Japanese vocabulary because of the similarity of the

Yoshiko Okuyama

371

symbols used in Romaji and the Roman alphabet. However, it was found that the

experimental group who learned the Japanese content words with Romaji in the

CALL program did not score higher in the posttests than the control group who

learned the same vocabulary without Romaji assistance. This nding was consistent with the results from both the sound and script posttests. The opportunity to

view Japanese vocabulary in Romaji had no effect on the number of words correctly identied by the students in the rst-semester Japanese classes.

JFL learners attitudes toward Romaji has been raised as a signicant variable in a survey study (Dewey, 2004). Is it possible that the results in the current

study were inuenced by the subject groups preference for Japanese script? In

the exit questionnaires, the students were asked whether the presence or absence

of Romaji would have helped them remember more Japanese words in the CALL

program. The responses from students in both groups were almost evenly divided:

25 students favored the Romaji assistance in the CALL program and 23 students

preferred the Japanese script only in the program. (The rest of the students were

undecided on the issue.) Of greater importance, these orthographic preferences

were evenly distributed between the control and experimental groups. Thus, the

beginning-level Japanese learners personal beliefs about Romaji were unlikely to

have affected the overall L2 vocabulary outcome.

Is it possible that the students in the experimental group did not pay attention

to Romaji because of their solid familiarity with the hiragana syllabary? As many

JFL practitioners can attest, it is highly unlikely that students in rst-semester

Japanese can fully master the Hiragana syllabary within the rst few weeks of

instruction. Their knowledge of the syllabary tends to be shaky until the end of

the semester. The reaction time data of the study showed that those who viewed

the vocabulary items with Romaji during the CALL lessons were slightly faster in

matching L2 audio cues with correct meanings. This nding may suggest that the

students in the experimental group made use of Romaji to some extent. The difference in reaction time between the two groups may imply that Romaji assisted the

experimental group in speeding up the activation of lexical memory, but it should

be remembered that the difference was not statistically signicant.

Contrary to the pedagogical assumptions supporting the use of Romaji, such

orthographic assistance did not have an impact on beginning-level CALL-based

vocabulary learning in Japanese. Hatasas (2002) study on the classroom use of

Romaji provided evidence that conrms this nding. Students who were taught

with the prolonged use of Romaji in class did not perform signicantly better

on their midterm and nal exams than those who had an early introduction of

authentic Japanese orthography. No effects of the use of Romaji were found either on their short-term or long-term development of Japanese prociency at the

introductory level in Hatasas study. Therefore, once Hiragana script has been

introduced, JFL beginners are ready to handle the learning burden of L2 written

forms (Nation, 2001) in acquiring basic Japanese words.

What are possible explanations for the lack of effects of Romaji assistance,

then? One explanation may come from the orthographic depth hypothesis (Katz

& Frost, 1992) and the correlation between orthographic transparency and the

372

CALICO Journal, Vol. 24, No. 2

ease in developing L1 word recognition skills (Ehri, 1999; Ellis & Hooper, 2001;

Fender, 2003; Seymour, Aro, & Erskine, 2003; Ellis et al., 2004; Kim, Davis,

Burnham, & Luksaneeyanawin, 2004). For example, in an experimental study

(Ellis et al., 2004), Japanese elementary school children rarely made errors in

reading the target words in the transparent script of Hiragana but were not so

successful with the opaque script of Kanji. Similarly, Greek children were more

successful at reading the words due to the transparent script of Greek with highly

regular grapheme-to-phoneme mappings than English-speaking children in the

same grades whose orthography is far less transparent than the Greek writing

system. Ellis et al. concluded that it is much harder to learn to read aloud in

orthographically opaque scripts (p.455) and that self-teaching might be more

difcult in orthographically opaque scripts than in transparent ones (p.456).

Kim et al. (2004) examined the visual sensitivity of Thai readers and Korean

Hangul readers. Thai is written in 72 alphabetic symbols of some visual complexity (e.g., many similar looking symbols), yet has high regularity between symbol

and sound. Hangul, on the other hand, is a script of 24 alphabetic symbols that

has a clear one-to-one match with Korean phonology and presents phonologically

similar phonemes, such as /n/, /d/, and /t/, with visually similar graphemes. They

found that the nature of Thai orthography demands higher visual sensitivity in

processing words and that the lack of such sensitivity negatively affects readers of

Thai, but not Hangul readers. In a similar study, Kim and Davis (2004) also found

that visual processing problems did not result in poor reading in Hangul because

the Korean orthography is visually transparent. Drawing from these ndings, one

can speculate that L2 vocabulary is more easily learned in a transparent script

(e.g., Japanese Hiragana and Korean Hangul) than in an opaque script (e.g., Japanese Kanji and the English alphabet) and that it is more likely for L2 learners to

become self-sufcient in decoding new words in transparent orthographies early

in the learning process. Once Hiragana is introduced to JFL learners, reverting to

the Roman alphabet does not appear to bring pedagogical merit to their beginning-level vocabulary learning.

CALL Strategies

In the second set of analyses, the frequency of using the sound button to access

audio recordings was strongly correlated with higher scores in both the sound and

script recognition posttests. Hegelheimer and Tower (2004) also found a close

relationship between achievement and repetitive use of L2 audio. On the other

hand, the strategy of spending more time in the CALL program was found to

only marginally inuence L2 vocabulary retention. In other words, time on task

had little impact on the number of words recalled. This was also similar to what

Hegelheimer and Tower (2004) discovered. The students who frequently used the

dialogue recordings stayed in the program for a longer period of time mainly because the auditory presentation of each dialogue took longer than that of a single

word. Thus, although those who listened to the dialogues took longer to complete

the CALL lessons, the length of CALL learning time per se was not a strong

Yoshiko Okuyama

373

predictor of vocabulary learning. The other tools available in the CALL software,

such as the kana tutor and grammar review, were rarely utilized by the students

(the mean number of mouse clicks on the kana button was 1.9 and on the grammar

button 2.7) and had no impact on their vocabulary learning.

Why is accessing L2 sound so important in retaining newly learned words in

short-term memory? Baddeley (2000) distinguished between two domains of

working memory: verbal and visual-spatial. It has been widely accepted that word

recognition is primarily a phonological process in Hiragana, Hangul, or Pinyin

(Simpson & Kang, 1994; Kawakami et al., 2001; Kim & Davis, 2002; Chen et al.,

2002; Ellis et al., 2004) but more of a visual-spatial process in Chinese (Tavassoli, 1999; Sugishita & Omura, 2001; Ho, Chan, Tsang, & Lee, 2002; Chen et al.,

2002; Flaherty, 2003). For example, a neurolinguistic study (Chen et al., 2002)

provided fMRI images of different brain activities involved in native speakers

processing Chinese characters and its phonetic counterpart, Pinyin.

If Hiragana also requires a high degree of phonological processing in reading

words, English-speaking JFL beginners need not struggle as much due to their

prior experience with another phonological script, the English alphabet. Furthermore, the symbol-sound mapping of the Hiragana syllabary is much more consistent than that of English orthography. Thus, adding another phonetic script of high

regularity, Romaji, to the CALL program was probably redundant and did not

enable the students to store any more words than their short-term memory could

hold. From a pedagogical point of view, it might be more benecial for JFL beginners to develop the solid knowledge of all the Hiragana symbols and adequate

word recognition skills based on that knowledge. If Hiragana itself was a sufcient device for the students to learn new words on their own in this brief CALL

instruction, then mastering the syllabary within the rst year of Japanese learning

should be of high priority. If the use of a phonetic notation device enhances the

learning of Kanji (a logograph that demands more visual-spatial processing), then

having Hiragana might be sine qua non for learning more L2 words via Kanji

characters in the following years.

The current study demonstrated the important role of L2 sound in CALL vocabulary learning. The intensive use of audio recordings was linked to better lexical learning not only in the recognition of L2 sound form (Posttest 1) but also in

the recognition of L2 orthographic form (Posttest 2). If the use of audio recordings

has a substantial impact on L2 vocabulary retention, focus on L2 phonological

form needs to be recognized as an important CALL learning strategy. CALL users

should be encouraged to access the softwares audio input frequently if the goal

of an L2 task is to learn new words. Whether students prefer Romaji assistance

or not, as long as they utilize L2 audio intensively, they are likely to learn new

vocabulary more effectively in CALL-based materials.

Limitations of the Study

The implications of this study should be viewed in the light of some limitations.

First, the implication that introductory-level students benet not from reading in

374

CALICO Journal, Vol. 24, No. 2

Romaji but from listening to L2 sound applies only to the short-term learning of

L2 vocabulary. Second, the study focused on students receptive knowledge of L2

vocabulary acquired in a CALL environment and did not address how students

could develop productive knowledge of L2 vocabulary. Third, the main purpose

of this study was to examine the effects of Romaji assistance for JFL beginners

in CALL. The students represented in the study were rst-semester Japanese students who had become acquainted with the hiragana syllabary within the rst few

weeks of instruction. Thus, the ndings should not be interpreted as pedagogical

implications for those who have no familiarity with Japanese orthography. Last

of all, because of the correlational nature of much of the analysis in the study, the

results of the study do not offer evidence in support of a cause-effect relationship

between any variables.

Suggestions for Future Studies

Milton and Meara (1995) estimated that advanced learners of English as a Second

Language (ESL) possibly acquire about 2,500 words per year. If this estimate is

valid for any foreign language, successful vocabulary learning represents a very

important pedagogical agenda. We need to continue our investigation on how L2

words are learned through different tasks, at different levels, as well as for different effects (e.g., short-term vs. long-term retention). If L2 word recognition

is critical in developing L2 reading ability at later stages, research on Japanese

word recognition will help provide insight for L2 reading experts. Furthermore,

because the distance between L1 and L2 orthographic forms can burden L2 vocabulary learning, more studies need to be conducted on lexical acquisition in a

nonalphabetic language.

Although the results of this study did not show a measurable outcome for the

use of Romaji, one can investigate long-term effects of using Romaji by conducting subsequent experiments and following the same students over a semester or a

year. The long-term effects of Romaji need to be investigated because many JFL

textbooks and CALL materials still use Romaji, and many JFL students continue

to use it as a quick and easy note-taking device even after their learning materials

have completely shifted to the authentic orthography. Individual differences in

English speakers predisposition for Hiragana symbol learning (e.g., visual memory capacity) also need to be examined in a CALL environment.

Due to the rapid growth of distance learning courses in American higher education, more and more language courses are offered online. However, the display of

non-English fonts continues to pose challenges to course designers/instructors as

well as students. For instance, WebCT, one of the most popularly adopted instructional delivery systems in the US, cannot be easily applied to develop a Japanese

language course (e.g., the Java-supported chat of WebCT 4.1 does not allow users

to type in Japanese, resulting in some confusion and typos derived from Romaji

input). Continuing research on the interaction between learner outcomes and L2

script use will help bring about a better understanding of how students can effectively use CALL instructional materials in Asian languages.

Yoshiko Okuyama

375

CONCLUSION

The primary goal of this study was to explore the role of L2 orthography in computer-assisted Japanese vocabulary learning. What this study revealed was strong

evidence for the advantage of using, not Romaji assistance, but rather L2 audio recordings. The insights from the study are perhaps most applicable to future

development of CALL software or for CALL vocabulary research. Nowadays,

there are many commercially available CALL programs for JFL learners either

to supplement their classroom learning or to learn the language on their own.

With clear guidelines for language software use, teachers and students of foreign

languages are better able to make pedagogically wise decisions. For the adequate

incorporation of CALL materials into a classroom curriculum, SLA researchers

need to explore empirically what works best in virtual learning environments.

NOTES

The Yookoso! textbook is designed to cover all the four language skills: listening, speaking, reading, and writing. Although the book presented all the regular chapters primarily

in Japanese orthography, the preliminary chapter is written all in Romaji as a transitional

phase.

1

The Learning Company kindly provided a sample copy of the original Learn to Speak

Japanese software and granted permission for its adaptation and use in this study.

2

3

The HyperCard program was used to program all the three modules. Each module was

created as a stack of cards, and the three stacks were linked in sequence for easy navigation.

REFERENCES

Akamatsu, N. (1999). The effects of rst language orthographic features on word recognition processing in English as a second language. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 11 (3), 381-403.

Akiyama, N., & Akiyama, C. (1995). Master the basics: Japanese. Hauppauge, NY: Barrons Educational Series.

Al-Seghayer, K. (2001). The effect of multimedia annotation modes on L2 vocabulary

acquisition: A comparative study. Language Learning & Technology, 5 (1), 202232. Retrieved October 30, 2006, from http://llt.msu.edu/vol5num1/AlSeghayer/

default.html

Ashworth, D. (1996). Hypermedia and CALL. In M. Pennington (Ed.), The power of CALL

(pp. 79-94). Houston, TX: Athelstan.

Ariew, R. (1991). Effective strategies for implementing language training technologies.

Applied Language Learning, 2 (2), 31-44.

Baddeley, A. D. (2000). The episodic buffer: A new component of working memory?

Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 4 (4), 417-423.

376

CALICO Journal, Vol. 24, No. 2

Chapelle, C., & Jamieson, J. (1991). Internal and external validity issues in research on

CALL effectiveness. In P. Dunkel (Ed.), Computer-assisted language learning

and testing: Research issues and practice. (pp. 38-59). New York: Newbury

House.

Chen, Y., Fu, S., Iversen, S. D., Smith, S. M., & Matthews, P. M. (2002). Testing for dual

brain processing routes in reading: A direct contrast of Chinese characters and

Pinyin reading using fMRI. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 14 (7), 10881098.

Chung, K. K. H. (2002). Effective use of Hanyu Pinyin and English translations as extra

stimulus prompts on learning of Chinese characters. Educational Psychology, 22

(2), 149-164.

Chung, K. K. H. (2003). Effects of Pinyin and rst language words in learning of Chinese

characters as a second language. Journal of Behavioral Education, 12 (3), 207223.

Collentine, J. (2000). Insights into the construction of grammatical knowledge provided

by user-behavior tracking technologies. Language Learning & Technology, 3

(2), 44-57. Retrieved October 30, 2006, from http://llt.msu.edu/vol3num2/col

lentine/index.html

Corda, A., & Van Der Stel, M. (2004). Web-based CALL for Arabic: Constraints and challenges. CALICO Journal, 21 (3), 485-495.

Dewey, D. P. (2004). Connections between teacher and student attitudes regarding script

choice in rst-year Japanese language classrooms. Foreign Language Annals,

37 (4), 567-579.

Ehri, L. C. (1999). Phrases of development in learning to read words. In J. Oakhill & R.

Beard (Eds.), Reading development and teaching of reading: A psychological

perspective (pp.79-108). Oxford: Blackwell.

Ellis, R. (1995). Modied oral input and the acquisition of word. Applied Linguistics, 16

(4), 409-41.

Ellis, N. C., & Hooper, A. M. (2001). It is easier to learn to read in Welsh than in English:

Effects of orthographic transparency demonstrated using frequency-matched

cross-linguistic reading tests. Applied Psycholinguistics, 22 (4), 571-599.

Ellis, N. C., Natsume, M., Stavropoulou, K., Hoxhallari, L., Van Daal, V. H. P., Polyzoe,

N., Tsipa, M., & Petalas, M. (2004). The effect of orthographic depth on learning

to read alphabetic, syllabic, and logographic scripts. Reading Research Quarterly, 39 (4), 438-468.

Fender, M. (2003). English word recognition and word integration skills of native Arabic- and Japanese-speaking learners of English as a second language. Applied

Psycholinguistics, 24 (2), 289-315.

Flaherty, M. (2003). Sign language and Chinese characters on visual-spatial memory: A

literature review. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 97 (4), 797-802.

Grace, A. C. (1995). Beginning CALL vocabulary learning: Translation in context. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, The University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona.

Hannas, W. C. (1997). Asias orthographic dilemma. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii

Press.

Yoshiko Okuyama

377

Hatasa, Y. A. (2002). The effects of differential timing in the introduction of Japanese syllabaries on early second language development in Japanese. The Modern Language Journal, 86 (3), 349-367.

Hegelheimer, V., & Tower, D. (2004). Using CALL in the classroom: Analyzing student

interactions in an authentic classroom. System, 32 (2), 185-205.

Ho, C. S.-H., Chan, D. W.-O., Tsang, S.-M., & Lee, S.-H. (2002). The cognitive prole and

multiple-decit hypothesis in Chinese developmental dyslexia. Developmental

Psychology, 38 (4), 543-553.

Hwu, F. (2003). Learners behaviors in computer-based input activities elicited through

tracking technologies. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 16 (1), 5-29.

Johnston, B., & Janus, L. (2003). Teacher professional development for the less commonly

taught languages. Minnesota University, Minneapolis. Center for Advanced Research on Language Acquisition. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No.

ED479299)

Kato, H., & Takada, N. (1994). Just listen n learn Japanese: Beginning through intermediate. New York: McGraw-Hill/Contemporary Books.

Katz, L., & Frost., R. (1992). Reading in different orthographies: The orthographic depth

hypothesis. In R. Frost & L. Katz (Eds.), Orthography, phonology, morphology,

and meaning (pp. 67-84). Amsterdam: New Holland.

Kawakami, A., Hatta, T., & Kogure, T. (2001). Differential cognitive processing of Kanji

and Kana words: Do orthographic and semantic codes function in parallel in

word matching tasks? Perceptual and Motor Skills, 93 (4), 719-726.

Kershul, K. (1992). Japanese in 10 minutes a day. Seattle, WA: Bilingual Books Inc.

Kim, J., Davis, C., Burnham, D., & Luksaneeyanawin, S. (2004). The effect of script on

poor readers sensitivity to dynamic visual stimuli. Brain and Language, 91 (1),

326-335.

Kim, J., & Davis, C. (2002). Using Korean to investigate phonological priming effects

without the inuence of orthography. Language & Cognitive Processes, 17 (6),

569-592.

Koda, K. (1997). Orthographic knowledge in L2 lexical processing: A cross-linguistic perspective. In J. Coady & T. Huckin (Eds.), Second language vocabulary acquisition: A rationale for pedagogy (pp. 35-52). New York: Cambridge University

Press.

Kudo, Y. (1999). L2 Vocabulary Learning Strategies. NFLRC NetWork #14, 1-46.

Learn to speak Japanese [Computer software]. (1994). Knoxville, TN: HyperGlot Software Company.

Laufer, B. (1997). Whats in a word that makes it hard or easy: some intralexical factors

that affect the learning of words. In N. Schmitt & M. McCarthy (Eds.), Vocabulary description, acquisition and pedagogy (pp.140-155). New York: Cambridge

University Press.

Laufer, B. & Hill, M. (2000). What lexical information do L2 learners select in a CALL

dictionary and how does it affect word retention? Language Learning & Technology, 3 (2), 58-76. Retrieved October 30, 2006, from http://llt.msu.edu/vol3num2/

laufer-hill/index.html

378

CALICO Journal, Vol. 24, No. 2

Liou, H. (2000). Assessing learner strategies using computers: New insights and limitations. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 13 (1), 65-78.

Matsunaga, S. (1995). The role of phonological coding in reading kanji: A research report

and some pedagogical implications (Technical Report #6). Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Second Language Teaching and Curriculum Center.

Matsunaga, S. (2001). Subvocalization in reading kanji: Can Japanese texts be comprehended without it? In H. Nara (Ed.), Advances in Japanese language pedagogy

(pp. 30-46). Columbus, OH: The National East Asian Languages Resource Center.

Makino, S., Hatasa, Y. A., Hatasa, K. (1998). Nakama 1: Japanese communication, culture,

context. New York: Houghton Mifin Company.

McMeniman., M. (1997). Introduction. Setting the Australian context: The teaching and

learning of languages and technology. In M. McMeniman & N. Viviano (Eds.),

The role of technology in the learning of Asian languages: A report on the Grifth

University National Priority Reserve Fund Project (pp. 5-10). Melbourne, Australia: Language Australia.

Milton, J., & Meara, P. M. (1995). How periods abroad affect vocabulary growth in a foreign language. Issues in Teaching Languages, 107-108, 17-34.

Muljani, D., Koda, K., & Moates, D. (1998). The development of word recognition in a

second language. Applied Psycholinguistics, 19 (1), 99-113.

Nagata, N. (2004). Robo-Sensei: Personal Japanese tutor [Computer software]. Boston:

Cheng & Tsui Company.

National Standards in Foreign Language Education Project (1999). Standards for foreign

language learning in the 21st century (2nd ed.). Lawrence, KS: Allen Press.

Nation, I. S. P. (2001). Learning vocabulary in another language. New York: Cambridge

University Press.

NihongoWare 1: An interactive approach to learning Business Japanese [computer software]. (1992). Webster, NY: Ariadne Language Link Co.

Okamura, Y. (1995). Students and nonteachers perception of elementary learners spoken

Japanese. The Modern Language Journal, 79 (1), 29-40.

Seymour, P. H. K., Aro, M., & Erskine, J. M., (2003). Foundation literacy acquisition in

European orthographies. British Journal of Psychology, 94 (2), 143-174.

Simpson, G. B., & Kang, H. (1994). The exible use of phonological information in word

recognition in Korean. Journal of Memory and Language, 33 (3), 319-331.

Singleton, D. (1999). Exploring the second language mental lexicon. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Sugishita, M., & Omura, K. (2001). Learning Chinese characters may improve visual recall. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 93 (3), 579-594.

Sumiyoshi, C., Sumiyoshi, T., Matsui, M., Nohara, S., Yamashita, I., Kurachi, M., & Niwa,

S. (2004). Effect of orthography on the verbal uency performance in schizophrenia: Examination using Japanese patients. Schizophrenia Research, 69 (1),

15-22.

Yoshiko Okuyama

379

Tan, L. H., Spinks, J. A., Feng, C., Siok, W. T., Perfetti, C. A., Xiong, J., Fox, P. T., & Gao,

J. (2003). Neural systems of second language reading are shaped by native language. Human Brain Mapping, 18 (1), 158-166.

Tavassoli, N. T. (1999). Temporal and associative memory in Chinese and English. Journal

of Consumer Research, 26 (2), 170-187.

Tohsaku, Y. (1994). Yookoso!: An invitation to Japanese. New York: McGraw-Hill.

TriplePlay Plus! Japanese [computer software]. (1994-1997). Syracuse, NY: Syracuse

Language Systems.

Vincent, E., & Hah, M. (1996). Strategies employed by users of a Japanese computer assisted language learning (CALL) program. Australian Journal of Educational

Technology, 12 (10), 25-34.

Wong, M., Perfetti, C. A., & Liu, Y. (2003). Alphabetic readers quickly acquire orthographic structure in learning to read Chinese. Scientic Studies of Reading, 7

(2), 183-208.

AUTHORS BIODATA

Yoshiko Okuyama is Assistant Professor in the Department of Languages at the

University of Hawaii at Hilo (UHH). While working at UHH, she completed her

dissertation and earned her Ph.D. from the University of Arizona in 2000. She

currently teaches courses in Japanese, introductory linguistics, psycholinguistics,

and second language acquisition theory and has served as UHH Language Lab

Coordinator.

AUTHORS ADDRESS

Yoshiko Okuyama, Ph.D.

Department of Languages

The University of Hawaii at Hilo

PO Box 6917

Hilo, HI 96720

Phone: 808 982 9871

Fax:

808 974 7736 (Attn: Yoshiko Okuyama)

E-mail: yokuyama@hawaii.edu

380

CALICO Journal, Vol. 24, No. 2

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Japanese LanguageDocumento18 pagineJapanese LanguageKiran100% (1)

- Do Japanese ESL Learners Pronunciation Errors ComDocumento36 pagineDo Japanese ESL Learners Pronunciation Errors ComSuNessuna valutazione finora

- ACQUISITION OF JAPANESE PITCH ACCENT BY AMERICAN LEARNERS - 43 Heinrich - Sugita 11Documento23 pagineACQUISITION OF JAPANESE PITCH ACCENT BY AMERICAN LEARNERS - 43 Heinrich - Sugita 11Ryosuke HoriiNessuna valutazione finora

- Japanese Pronunciation of English AnalyzedDocumento18 pagineJapanese Pronunciation of English AnalyzedAnh LêNessuna valutazione finora

- Effects PronunciationDocumento16 pagineEffects PronunciationwatmaliaNessuna valutazione finora

- FSI - Igbo Basic Course - Student TextDocumento512 pagineFSI - Igbo Basic Course - Student TextNwamazi Onyemobi Desta AnyiwoNessuna valutazione finora

- Riney-Japanese Pronunciation of English 1993Documento18 pagineRiney-Japanese Pronunciation of English 1993Tabitha SandersNessuna valutazione finora

- Assimilation of English Vocabulary Into The Japanese LanguageDocumento13 pagineAssimilation of English Vocabulary Into The Japanese LanguageDavid AriasNessuna valutazione finora

- Translation Equivalence Vs Translation Equivalents Quantifying Lexical and Syntactic Examples of Japanese EnglishDocumento12 pagineTranslation Equivalence Vs Translation Equivalents Quantifying Lexical and Syntactic Examples of Japanese EnglishM ZainalNessuna valutazione finora

- Contrasting English and Hausa PhonemesDocumento7 pagineContrasting English and Hausa PhonemesUnknownNessuna valutazione finora

- Five Myths About KanjiDocumento28 pagineFive Myths About Kanjigdanieli100% (1)

- 584 - 165523 - Module 1 Historical Development of HiraganaDocumento4 pagine584 - 165523 - Module 1 Historical Development of HiraganaNerizza SomeraNessuna valutazione finora

- Phraseology in A Learner Corpus Compared With The Phraseology of UK and US StudentsDocumento26 paginePhraseology in A Learner Corpus Compared With The Phraseology of UK and US StudentsNurinsiahNessuna valutazione finora

- Issues in Applied Linguistics: TitleDocumento4 pagineIssues in Applied Linguistics: TitleGabriel BispoNessuna valutazione finora

- Japanese Adjective Conjugation Patterns and SourceDocumento17 pagineJapanese Adjective Conjugation Patterns and SourceCoping Forever100% (1)

- Kyukiyo9 177-188 PDFDocumento12 pagineKyukiyo9 177-188 PDFThakur Tarun ChauhanNessuna valutazione finora

- 001-018 Sachiyo TakanamiDocumento18 pagine001-018 Sachiyo TakanamiLocNguyenNessuna valutazione finora

- English Teaching Journal November 2016Documento141 pagineEnglish Teaching Journal November 2016Kiều LinhNessuna valutazione finora

- Kinesthetic gestures boost EFL learners' intonationDocumento7 pagineKinesthetic gestures boost EFL learners' intonationDanicaNessuna valutazione finora

- Challenges in Teaching English Conversation: Donna EricksonDocumento5 pagineChallenges in Teaching English Conversation: Donna EricksonRumana FatimaNessuna valutazione finora

- Grammar Instruction and Learning StyleDocumento26 pagineGrammar Instruction and Learning StyleHa DangNessuna valutazione finora

- Anderson, AN IN-DEPTH EXPLORATION OF THE ADOPTION OF ENGLISH LOANWORDS IN SPANISH AND JAPANESEDocumento20 pagineAnderson, AN IN-DEPTH EXPLORATION OF THE ADOPTION OF ENGLISH LOANWORDS IN SPANISH AND JAPANESEdenisa.salvova5Nessuna valutazione finora

- 'Re Marking' FilipinoDocumento30 pagine'Re Marking' FilipinoMichaella AzoresNessuna valutazione finora

- Pronunciation Difficulties Analysis - A Case Study PDFDocumento9 paginePronunciation Difficulties Analysis - A Case Study PDF7YfvnJSWuNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction To JapaneseDocumento40 pagineIntroduction To Japanesesiloha100% (1)

- Elt 224 - Week 1-3Documento21 pagineElt 224 - Week 1-3Sofia NicoleNessuna valutazione finora

- Teaching English With The IPA: Josef Messerklinger, Asia UniversityDocumento7 pagineTeaching English With The IPA: Josef Messerklinger, Asia UniversityKyaw Zin Phyo HeinNessuna valutazione finora

- Four Ways Japanese Isn't The Hardest Language To LearnDocumento3 pagineFour Ways Japanese Isn't The Hardest Language To LearnErmhs SmaragdeniosNessuna valutazione finora

- 2 Contrastive Analysis of The Segmental Phonemes ofDocumento7 pagine2 Contrastive Analysis of The Segmental Phonemes ofSamuel EkpoNessuna valutazione finora

- Review of Recent Research On Kani Processing, Leaning, and Instruction - MoriDocumento29 pagineReview of Recent Research On Kani Processing, Leaning, and Instruction - MoriJanea Rayelle CalderaNessuna valutazione finora

- ANSWER: Japanese (Or Nihongo)Documento3 pagineANSWER: Japanese (Or Nihongo)Tony WeeksNessuna valutazione finora

- My Text Book 2Documento1 paginaMy Text Book 2JOSHUA MANIQUEZNessuna valutazione finora

- PCM Reviewer FinalDocumento18 paginePCM Reviewer Finalalliana marieNessuna valutazione finora

- The Effects of First Language Orthographic Features On Word Recognition Processing in English As A Second LanguageDocumento24 pagineThe Effects of First Language Orthographic Features On Word Recognition Processing in English As A Second LanguageReiraNessuna valutazione finora

- How Pronunciation Is Taught in English Textbooks Published in JapanDocumento34 pagineHow Pronunciation Is Taught in English Textbooks Published in JapanDwi RachelNessuna valutazione finora

- PRAGMATIC MAKerDocumento16 paginePRAGMATIC MAKerMaria UlfaNessuna valutazione finora

- 13 Natures of LanguageDocumento14 pagine13 Natures of LanguageGerald Lasheras DM0% (1)

- Course - JapaneseDocumento324 pagineCourse - JapaneseMartin Biblios100% (1)

- Analysis of lexical errors in English compositions by Thai learnersDocumento23 pagineAnalysis of lexical errors in English compositions by Thai learnersHameed Al-zubeiryNessuna valutazione finora

- The Distinctive Phonologic Feature of Korean English LearnersDocumento11 pagineThe Distinctive Phonologic Feature of Korean English LearnersJan Patrick ArrietaNessuna valutazione finora

- Issues in Applied Linguistics: TitleDocumento24 pagineIssues in Applied Linguistics: TitleĐạt Vũ Súc VậtNessuna valutazione finora

- OpenCourseWare Classical Japanese GrammaDocumento167 pagineOpenCourseWare Classical Japanese GrammaXYNessuna valutazione finora

- Segmental and Suprasegmental Analysis: A Case Study of A Malay Learner's Utterances of An English SongDocumento20 pagineSegmental and Suprasegmental Analysis: A Case Study of A Malay Learner's Utterances of An English SongMuhammad MuzzammilNessuna valutazione finora