Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Eurozone Crisis. Grexit.

Caricato da

Rishi ShahCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Eurozone Crisis. Grexit.

Caricato da

Rishi ShahCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Many observers of the Eurozone debt crisis argue that the Euro can only survive if the common

currency is complemented by a fiscal union. But theres a problem with that: Fiscal union,

mostly understood as a combination of centralized control over public finances with joint

guarantees for government debt, is a fundamentally flawed concept. The political integration

required to achieve it is not in sight. In order for a fiscal union to work, national governments

including parliaments would have to give up the right to set taxes and determine public

expenditure independently and accept a restriction of national sovereignty in other areas of

economic and social policy. The debate about the fiscal compact has shown that most member

countries, in particular France, are not willing to conform. This is an understandable position

considering the absence of democratic control at the EU level with decisions made in Brussels

about key issues like national taxes and expenditures, which directly affect most citizens, simply

lacking legitimacy.

A much more promising approach than fiscal union would be to focus on a Europeanization of

the banking sector. This would require a complete shift of banking regulation and supervision to

the European level and the creation of a European bank resolution mechanism. A key aspect of

this Europeanization would be that banks would no longer be allowed to hold as many domestic

government bonds as they do today. Politically, a Europeanization of the banking sector would

also require countries to give up sovereignty, but in the area of banking regulation and

supervision, which is rather technocratic and more remote from day-to-day concerns of ordinary

citizens. It would be politically much more acceptable to delegate this task to an independent

European body like the European Central Bank than to relinquish the right to set fiscal policy.

One of the key difficulties in overcoming the Euro debt crisis is that the current financial system

is characterized by a close symbiosis between national governments and national banking

systems. The situation in Spain offers a good example. The Spanish banking system is plagued

by huge and unrealized losses from the financing of the real estate bubble. At the same time,

Spanish banks are massively invested in government bonds and the Spanish government puts

pressure on Spanish banks to buy more bonds if funds are available. This undermines the ability

of the banking system to provide credit to sectors which might contribute to an economic

recovery. Financial difficulties of the Spanish government threaten the stability of the Spanish

banking system and vice versa.

A Europeanization of the banking sector would improve the Eurozone situation. Since banks

would be less exposed to their national governments, financial sector stability would be less

endangered if a national government has financial problems. In addition, the finances of national

governments would not be endangered by problems of national banks, because collapsing banks

would be restructured or recapitalized at the European level, rather than threatening to draw their

national governments into bankruptcy. Providing funds at the European level is possible because

control over, and supervision of, the banking system also takes place at the European level. In

the US, for instance, financial problems of the state of California are less dramatic for

Californian banks because their activities and asset holdings are more diversified across the US.

If a bank faces financial difficulties, funds required to restructure or recapitalize the bank would

not have to come from the California government, but rather from a federal institution.

Europe is debilitated by the effects of two years of desperate crisis

management. The prescribed treatment resembles the old practice of

bloodletting on ailing patients. Growing debts are paid with more loans, and

new loans are made dependent on increasingly severe austerity measures. The

results are a greater risk of recession, higher interest rates on refinancing

loans, and the need for runaway financial aid to the southern eurozone

countries. Greece is a dramatic portent of the direction things could take.

Record-breaking unemployment of over 22% in Spain and record interest

rates on Portuguese bonds show that the crisis fever is far from abating.

Portugal, Spain and even Italy have still not managed to extricate themselves

from the downward spiral of recession and debt. It is a vicious circle that

increases the risk of a split in the eurozone something that would have been

unthinkable in 2009.

It has taken two years of futile efforts for governments to finally start talking

about growth and employment as European aims again. This change in

attitude is prompted by shock. The credit-rating downgrades for France, eight

other eurozone countries and the European Financial Stability Facility bailout

fund at the start of the year all show that the capital markets are predicting a

downward spiral. It was particularly insightful to see how Standard & Poor's

justified the downgrades: "We believe that a reform process based on a pillar

of fiscal austerity alone risks becoming self-defeating, as domestic demand

falls in line with consumers' rising concerns about job security and disposable

incomes, eroding national tax revenues."

We need to set a new course now and implement a far more consistent and

precise strategy. First and most importantly: the current situation requires us

to create the right conditions to ensure private capital flows into the real

economies of crisis countries. For this to happen, there needs to be a

guarantee that these crisis countries and their banks can pay their debts

from a robust European Stability Mechanism, which can provide itself with

liquidity from the European Central Bank, and a common debt-reduction pact

as suggested by the German Council of Economic Experts. Growth needs

private investment, and these investments need security!

Secondly, we need to remove any obstacles to investing in Europe and give

hope for an upturn in the economy in order to bring back hesitant private

investors who have lost confidence. Our most important task is therefore to

create a comprehensive European investment programme, which will increase

the competitiveness of crisis countries, expand Europe's industrial

infrastructure particularly its energy networks and promote research and

development. In order to ensure that the momentum of change is not lost in

excessive red tape, the European Investment Bank must play a central role. A

crucial aspect of the project is that it will not be financed by new debts, but by

a European financial transaction tax, which could bring in up to 50bn

if Europe or at least the eurozone is united on the issue. For European

solidarity has two meanings and it is time to show we are committed to both.

Taxing financial markets, promoting research and development, and

mobilising investments: that means learning our lessons from the financial

market crisis and changing our focus. "It's the real economy, stupid!" is a call

now even heard from Anglo-Saxon nations. For a decade "industrial policy"

was one of the most unfashionable terms in politics. But we are now done with

bowing to the demands of the financial industry. Germany's strength the

strength that has made us the anchor of Europe is the result of many years

of hard work to maintain and modernise industrial production. It is also the

fruit of our refusal to follow the trendy yet mistaken teachings of London and

Davos, which accelerated the flywheel of the financial markets by a few

rotations each year. We want less subjugation to a system of mere value

absorption and more respect for the laborious process of value creation this

demand does not come from Occupy Wall Street, but from the management

boards of German industrial companies. We must recognise the larger global

challenge that lies beneath the European financial market and debt crisis.

China will have overtaken the US in terms of gross domestic product by 2020.

Europe's demography is developing towards a smaller working population in

an ageing society. Resources are becoming scarcer. If we want to promote new

growth, we should focus on the quality of the value we are creating. GDP

growth at any cost and quick financial market profits at the price of bad

working conditions and a wasted environment is not a solution, as recent news

like that of Schlecker's bankruptcy has shown us once again.

Europe has the potential to pioneer and supply a sustainable worldwide

economy. Achieving this means addressing the major global challenges:

keeping healthy well into old age, using energy efficiently and from renewable

sources, and ensuring mobility while fossil fuels become scarcer and more

expensive. These problems require real solutions. To find them, we need

excellent researchers, developers, engineers and specialists. The economy of

the future needs an industry of the future. In the global division of labour,

Europe's role must be to conceive, develop and provide new products for a

sustainable economic model built to ensure the prosperity of almost 9 billion

people. That is the current state of the European dream.

Crucially, the Eurozone comprises a number of heterogeneous economies and

is almost certainly not an Optimal Currency Area (OCA). Each country has its

own economic structure, its own institutions, and its own set of fiscal policies.

Individual member states gave up control of important macroeconomic policy

levers such as monetary and exchange rate policy when the Euro was

adopted. These key policy levers were not adequately replaced and this left

individual member states particularly vulnerable to asymmetric shocks and to

divergences in competitiveness. But this does not imply that full fiscal

federalism is a necessary requirement of a successful monetary union. A

commitment to fiscal union is unnecessary. Instead, what is required is a

centralised insurance fund to ameliorate the impact of recession and severe

asymmetric shocks, combined with intergovernmental coordination of policies

to prevent competitiveness and fiscal imbalances from growing too large. An

inter-regional insurance scheme to provide fiscal transfers in a counter

cyclical manner could be funded by a pan Eurozone consumption tax

hypothecated for and paid directly to the centralised insurance fund. The

fund would be mandated to run a surplus over the economic cycle and could

be called upon under strict guidelines to provide direct fiscal support on a

temporary basis to countries suffering recession or a severe asymmetric

shock. The funding should be automatic subject to the conditions and terms

of access agreed annually by Eurozone governments.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Ju Complete Face Recovery GAN Unsupervised Joint Face Rotation and De-Occlusion WACV 2022 PaperDocumento11 pagineJu Complete Face Recovery GAN Unsupervised Joint Face Rotation and De-Occlusion WACV 2022 PaperBiponjot KaurNessuna valutazione finora

- Understanding CTS Log MessagesDocumento63 pagineUnderstanding CTS Log MessagesStudentNessuna valutazione finora

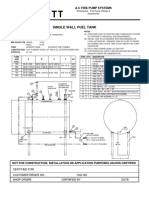

- Single Wall Fuel Tank: FP 2.7 A-C Fire Pump SystemsDocumento1 paginaSingle Wall Fuel Tank: FP 2.7 A-C Fire Pump Systemsricardo cardosoNessuna valutazione finora

- Fujitsu Spoljni Multi Inverter Aoyg45lbt8 Za 8 Unutrasnjih Jedinica KatalogDocumento4 pagineFujitsu Spoljni Multi Inverter Aoyg45lbt8 Za 8 Unutrasnjih Jedinica KatalogSasa021gNessuna valutazione finora

- Salary Slip Oct PacificDocumento1 paginaSalary Slip Oct PacificBHARAT SHARMANessuna valutazione finora

- QSK45 60 oil change intervalDocumento35 pagineQSK45 60 oil change intervalHingga Setiawan Bin SuhadiNessuna valutazione finora

- Customer Satisfaction and Brand Loyalty in Big BasketDocumento73 pagineCustomer Satisfaction and Brand Loyalty in Big BasketUpadhayayAnkurNessuna valutazione finora

- 01 Automatic English To Braille TranslatorDocumento8 pagine01 Automatic English To Braille TranslatorShreejith NairNessuna valutazione finora

- Battery Impedance Test Equipment: Biddle Bite 2PDocumento4 pagineBattery Impedance Test Equipment: Biddle Bite 2PJorge PinzonNessuna valutazione finora

- 21st Century LiteraciesDocumento27 pagine21st Century LiteraciesYuki SeishiroNessuna valutazione finora

- Hardened Concrete - Methods of Test: Indian StandardDocumento16 pagineHardened Concrete - Methods of Test: Indian StandardjitendraNessuna valutazione finora

- Entrepreneurship WholeDocumento20 pagineEntrepreneurship WholeKrizztian SiuaganNessuna valutazione finora

- Lorilie Muring ResumeDocumento1 paginaLorilie Muring ResumeEzekiel Jake Del MundoNessuna valutazione finora

- Organisation Study Report On Star PVC PipesDocumento16 pagineOrganisation Study Report On Star PVC PipesViswa Keerthi100% (1)

- Mapping Groundwater Recharge Potential Using GIS-Based Evidential Belief Function ModelDocumento31 pagineMapping Groundwater Recharge Potential Using GIS-Based Evidential Belief Function Modeljorge “the jordovo” davidNessuna valutazione finora

- ITS America's 2009 Annual Meeting & Exposition: Preliminary ProgramDocumento36 pagineITS America's 2009 Annual Meeting & Exposition: Preliminary ProgramITS AmericaNessuna valutazione finora

- Econometrics Chapter 1 7 2d AgEc 1Documento89 pagineEconometrics Chapter 1 7 2d AgEc 1Neway AlemNessuna valutazione finora

- Social EnterpriseDocumento9 pagineSocial EnterpriseCarloNessuna valutazione finora

- Ralf Behrens: About The ArtistDocumento3 pagineRalf Behrens: About The ArtistStavros DemosthenousNessuna valutazione finora

- EWAIRDocumento1 paginaEWAIRKissy AndarzaNessuna valutazione finora

- CAP Regulation 20-1 - 05/29/2000Documento47 pagineCAP Regulation 20-1 - 05/29/2000CAP History LibraryNessuna valutazione finora

- Gates em Ingles 2010Documento76 pagineGates em Ingles 2010felipeintegraNessuna valutazione finora

- Portable dual-input thermometer with RS232 connectivityDocumento2 paginePortable dual-input thermometer with RS232 connectivityTaha OpedNessuna valutazione finora

- Safety QualificationDocumento2 pagineSafety QualificationB&R HSE BALCO SEP SiteNessuna valutazione finora

- 3) Stages of Group Development - To StudsDocumento15 pagine3) Stages of Group Development - To StudsDhannesh SweetAngelNessuna valutazione finora

- Max 761 CsaDocumento12 pagineMax 761 CsabmhoangtmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Learning HotMetal Pro 6 - 132Documento332 pagineLearning HotMetal Pro 6 - 132Viên Tâm LangNessuna valutazione finora

- Gerhard Budin PublicationsDocumento11 pagineGerhard Budin Publicationshnbc010Nessuna valutazione finora

- Arizona Supreme CT Order Dismisses Special ActionDocumento3 pagineArizona Supreme CT Order Dismisses Special Actionpaul weichNessuna valutazione finora

- Complaint Handling Policy and ProceduresDocumento2 pagineComplaint Handling Policy and Proceduresjyoti singhNessuna valutazione finora