Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

The Fall of Berlin

Caricato da

Mariella GiorginiCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

The Fall of Berlin

Caricato da

Mariella GiorginiCopyright:

Formati disponibili

The Fall of Berlin and the Rise of a Myth

Author(s): Donald E. Shepardson

Source: The Journal of Military History, Vol. 62, No. 1 (Jan., 1998), pp. 135-154

Published by: Society for Military History

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/120398 .

Accessed: 24/04/2011 22:47

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless

you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you

may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at .

http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=smh. .

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed

page of such transmission.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Society for Military History is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal

of Military History.

http://www.jstor.org

The Fall of Berlin and

the Rise of a Myth

Donald E. Shepardson

ON30 April 1945 a Russian soldier raised his flag over the Reichstag

building in Berlin to signal Stalin's defeat of Hitler after four years

of war.' The fall of Berlin also coincided with the rise of a grand myth of

American naivete and British realism in dealing with their German

enemy and Soviet ally during the spring of 1945. The British and Americans, it was said, could have taken Berlin before the Red Army, but

declined to do so because General Dwight Eisenhower was overly cautious and failed to perceive the coming Cold War with the Soviet Union.2

The myth was born amid conflicting American and British differences on wartime priorities and postwar anxieties as well as a feeling

among the British that their effort against Hitler was not fully appreciated. They had a point. For the better part of two years Britain had

fought alone before Hitler's aggression forced the Soviet Union and the

United States into war. It was also a myth generated by the stress and

personality conflicts endemic to coalition warfare. The controversy has

been portrayed as part of a personal feud between General Dwight Eisenhower and Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, or as the Americans

against the British. To some extent it was, but Eisenhower had his British

supporters, and no one favored driving for Berlin more than George Patton.3

1. The author sends a salute of appreciation to Colonel David Glantz for his help

in completing this manuscript.

2. David W. Hogan, Jr., "Berlin Revisited: Eisenhower's Decision To Halt At The

Elbe Viewed Fifty Years Later: A Selected Bibliography,"Headquarters Gazette 6

(Summer, 1995): 5.

3. Carlo D'Este,Patton: A Genius for War (New York:HarperCollins, 1995), 721.

The Journal of Military History 62 (January 1998), 135-54

0 Society for Military History

135

DONALDE. SHEPARDSON

Chester Wilmot criticized the decision to halt at the Elbe in his 1952

book, The Struggle For Europe.4 He has been joined by eminent historians such as Alan Bullock and Albert Seaton, with the latter wondering

"why Roosevelt and the United States Chiefs of Staff should have left this

final stage of the war to the discretion of a single individual who,

although a soldier of distinction, may at that time have been lacking in

political acumen and an understanding of the aims and methods of the

Soviet Union. Military objectives should of necessity have been related

to post-war political strategy."5

The myth has continued for fifty years despite the works of Stephen

Ambrose, Theodore Draper, David Eisenhower, Forrest Pogue, and others. In his recent book, Diplomacy, Henry Kissinger added his support.

"In April of 1945," he wrote, "Churchill pressed Eisenhower ... to seize

Berlin ahead of advancing Soviet Armies." The American refusal,

Kissinger believes, was a prime example of "military planning unaffected

by political considerations." Berlin, Kissinger believes, was a free gift at

a time when "there were no significant German armed forces left to

destroy."6

Critics of American policy have assumed that in the spring of 1945

everyone should have known that the Cold War was inevitable. American leaders, however, still hoped to prevent a break with the Soviets and

were more concerned with winning World War II than striking the first

blow of World War III. "World War II may be refought," wrote Theodore

Draper, "only as an exercise in speculation and hindsight. The way it

... was fought gives no reason to believe that it would have gone entirely

right if it had been fought differently. . . . What we can do now is to

understand what hard choices had to be made and to put ourselves back

into that time and place, as if we had to face those hard choices as they

arose."7 More recently, Gerhard Weinberg has reminded us that historians too often judge the past on the basis of what came later rather than

on what came before. Those who made their decisions during the harsh

years of World War II, he wrote, "had their hopes and their fears, made

their guesses and their projections, but in the rush of events had only the

barest glimmer of possible future developments."8 When facing those

hard choices amid the rush of events in the spring of 1945, it was Eisen-

4. Chester Wilmot, The Struggle for Europe (New York:Harper, 1952), 690-706.

5. Alan Bullock, Hitler and Stalin: Parallel Lives (New York:Knopf, 1992), 884;

Albert Seaton, The Russo-German War,1941-45 (New York:Praeger, 1971), 563.

6. Henry Kissinger,Diplomacy (New York:Simon and Schuster, 1994), 417.

7. Theodore Draper,"Eisenhower'sWar,"New YorkReview of Books 33 (25 September 1986): 30.

8. Gerhard L. Weinberg, Germany, Hitler, and World War II: Essays in Modern

German and WorldHIistory(Cambridge:Cambridge University Press, 1995), 287.

136

THE JOURNAL OF

The Fall of Berlin and the Rise of a Myth

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

.

. . . . . .........

,,.......

v,St

,': ........... .. ........

...

6?y

Z{&

9aJ4 c

/

_g

;o

......

~~~~~~~~~~of

q,L

~t

US 3d

Soviet

rmles--

>I1||||||J

.. .

Switzerland

i1

Yalta CoDn

t~~

^5

g

Fr

at time

<FroFrnt

Ital

_t<

u|_

...........

?__

e _KL

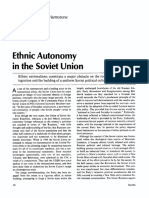

The situation in Western Europe between the Yalta Conference (4-9 Feb-

ruary 1945) and V-EDay (9 May 1945). Shown are thefronts at the time

of the Conference,the borderbetween the Soviet occupation zone and the

British and American zones decided upon at the conference, and the

final lines reached by the Allied armies. The dark areas weerestill occupied by German forces on V-E Day.

hower and his superiors who were the more realistic and not their critiCS.

Following the Battle of the Bulge in December of 1944, the Wehrmacht ceased to mount well-coordinated resistance to the advancing

western Allies. Many German soldiers, however, were still willing to fight

ably and tenaciously for Fatherland and Fuhrer up to the end of the war.

In the East the Red Army had lain relatively dormant on the Vistula

since the summer of 1944. Stalin had told his Western Allies that he

would launch an offensive in January of 1945 to coincide with their drive

on the Rhine. Neither his allies nor the Germans expected it to come on

such a massive scale.

MILITARY HISTORY

137

DONALDE. SHEPARDSON

Stalin was now looking beyond the Oder to Berlin and perhaps to the

Elbe for a final defeat of the Germans. Throughout the autumn the Red

Army built up its forces to a five-to-one advantage, stockpiled supplies,

and converted needed portions of the Polish rail system to the wider

Russian gauge.9

On 12 January, the Red Army struck in force under the leadership

of Marshals Georgi Zhukov and Ivan Konev. Their advance accelerated in

the flatlands of western Poland, and by the end of the month they had

reached the Oder. The Red Army now faced its "February Dilemma."

Berlin lay less than fifty miles ahead. Zhukov and the Soviet command

in Moscow initially believed they could reach the Elbe by the end of February, and then attack Berlin from several directions.

But German fortifications and troop concentrations still had to be

eliminated. In their rapid advance the Russians had also exposed their

flanks to German attacks, especially along Zhukov's salient in the center.

These factors, in addition to growing supply problems, German reinforcements, and bad weather, caused concern in Moscow and at the front.

Stalin decided to postpone any assault on Berlin. In three weeks his

Red Army had won one of the most spectacular strings of victories of the

war. He could now meet his Allies at Yalta on 4 February with all of

Poland and most of Hungary in his pocket. His armies were little more

than a day's march from Berlin, while those of his allies were still fighting to regain the area lost during the Battle of the Bulge.'0 There was no

point in taking any risks. In Europe, as well as Asia, his allies needed him

more than he needed them. Given the military situation, Secretary of

State Edward R. Stettinius, Jr., later wrote, "it was not a case of what the

United States and Great Britain would permit Russia to do, but what the

two countries could persuade the Soviet Union to accept."11

In the West, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of

the Allied Expeditionary Force, expected a tough fight before victory,

and he realized more than anyone how dependent his armies were on

the Red Army closing from the East. On 15 January he told General

9. Tony Le Tissier,Zhukov at the Oder: The Decisive Battlefor Berlin (Westport,

Conn.: Praeger, 1996), 13; Gerhard Weinberg,A Worldat Arms: A Global History of

World War II (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 798-802; Earl P.

Ziemke, Stalingrad to Berlin (Washington: Office of the Chief of Military Ilistory,

1968), 419-21.

10. David M. Glantz and Jonathan M. lIouse, When 7itans Clashed: How the Red

Army Stopped Hitler (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1995), 249-50; Seaton,

Russo-Gerrnan War, 536-37; Raymond Cartier, Der zweite Weltkrieg (Miunchen:

Piper, 1967), 2: 952-53; John Erickson, The Road To Berlin: Continuing the Story of

Stalin's War with Germany (Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 1983), 472-76.

11. Edward R. Stettinius, Jr., Roosevelt and the Russians: The Yalta Conference

(Garden City, N.Y.:Doubleday, 1949), 301.

138

THE JOURNAL OF

The Fall of Berlin and the Rise of a Myth

George Marshall, Chief of Staff of the Army, that if the Russian offensive

was weak, the Germans could maintain enough strength in the West to

stop his own advance.12 With a strong Russian offensive, however, Eisenhower planned to move on the Rhine along a wide front, while remaining flexible enough to cross it at the first opportunity.

After regaining the areas lost to the Germans in the Ardennes, Eisenhower gathered strength and then launched his assault west of the

Rhine. On 20 January his forces began their attempt to clear the area in

Upper Alsace known as the Colmar Pocket. With the aid of American

units, French forces captured Colmar on the twenty-seventh. From there

the Allies moved against other enemy units until by 9 February German

forces had been eliminated on the west bank of the Rhine south of Strasbourg.

Before the Colmar Pocket had been cleared, the Allies launched a

series of attacks designed to clear the west bank of the Rhine while

destroying as many German forces as possible. Beginning with Operation

Veritable in the north and ending with Operation Undertone in the

south, the Allies struck like a series of firecrackers along the front. At

first the fighting was fierce against special SS units determined to fight

until the end, but gradually air and armored superiority took their toll.

From the middle of February onward, Allied armies advanced along the

entire front. The German defenders were handicapped by shortages of

supplies as well as delays caused by roads clogged with refugees and the

accumulated junk of retreating forces. In the face of mounting casualties

and sagging morale, more and more soldiers looked for the chance to

surrender. By the end of the month nearly 250,000 had done so, adding

their number to the over 300,000 casualties suffered by the Wehrmacht

during the Rhineland campaign.13

As Eisenhower's armies advanced, President Franklin D. Roosevelt

met with Winston Churchill and Joseph Stalin at Yalta from 4 to 11 February. Each of the leaders knew the European war would soon end. Most

of the conference dealt with the fate of Germany and Poland. Agreement

on temporary zones of military occupation and Soviet entry into the war

against Japan was relatively easy and harmonious. The zones had been

initially proposed and discussed at a time when the Western allies were

more concerned about meeting the Red Army at the Rhine than about

12. Stephen E. Ambrose, The Supreme Commander: The War Years of General

Dwight D. Eisenhower (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1970), 607; The Papers of

Dwight David Eisenhower: The War Years, ed. Alfred D. Chandler (Baltimore: Johns

IIopkins University Press, 1970), 4: 2430-31.

13. Ambrose, Supreme Commander, 615; Raymond Cartier, Der zweite

Weltkrieg, 2 vols. (Munich: Piper, 1967), 968-71; Forrest C. Pogue, The Supreme

Command, a volume in the series United States Army in WorldWar II (Washington:

GPO, 1954), 423, 427-29.

MILITARY HISTORY

139

DONALD E. SHEPARDSON

challenging it for control of Berlin. The Soviet zone comprised slightly

over one third of Germany and extended one hundred miles west of

Berlin. Berlin itself was divided into American, British, French, and

Soviet zones.14 The zones were agreed upon in part to forestall a lastminute land grab by any of the powers, and the confrontation that might

come with it. The political decision had been made.

Eisenhower's armies approached the Rhine while agreement on the

zones was completed. The rapid Allied advance placed the Germans in a

dilemma. The bridges over the river must be destroyed before the enemy

could use them. But blowing them too soon would leave many German

troops and their equipment trapped on the other side. The delay and

indecision involved in waiting long enough, but not too long, led to one

of those "breaks" of military fortune that alters plans, timetables, and

sometimes even the course of war itself.

On the afternoon of 7 March, units of the American Ninth Armored

Division approached the town of Remagen on the Rhine, some 250 miles

from Berlin. To their astonishment they saw the Ludendorff railroad

bridge still spanning the river intact. While planning to destroy the

bridge the Germans had lacked adequate explosives and had to improvise. They were surprised by the American infantry, and the Pershing

tanks supporting it. The tanks were able to silence German fire and in

the process may have cut wires leading to the explosive charges. The

first attempt to blow the bridge failed; the second appeared to be successful. The bridge shook but then settled back onto its moorings. American commanders decided to risk a crossing before another attempt was

made to destroy it. With the support of their tanks American infantry

became the first hostile troops since Napoleon's army of 1806 to cross

the Rhine. By the end of the day one tank company along with three

infantry companies had established a bridgehead on the other side.15

Crossing the Rhine accelerated the Allied drive into Germany. It also

brought new problems. Americans in the south were able to cross more

rapidly than British forces in the north. The American crossing seemed

even more important when Eisenhower received an intelligence report

on 11 March warning of German plans for a last defense in the mountains of southern Bavaria.

The existence of "the fortress that never was," as Rodney Minott

referred to it, could not be ignored.'6 The Germans had large concentra14. U.S. Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States: The Conferences at Malta and Yalta, 1945 (Washington:GPO, 1955), 118-27.

15. Cartier,Der zweite Weltkrieg , 971-72; Charles MacDonald, The Last Offensive, a volume in the series United States Army in WorldWar II (Washington:GPO,

1973), 213-17.

16. Rodney G. Minott, The Fortress that Never Was: The Myth of Hitler's Bavarian Stronghold (New York:Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1964), 35-37.

140

THE JOURNAL OF

The Fall of Berlin and the Rise of a Myth

tions of forces in the south, and it was the logical place for soldiers from

the Eastern, Italian, and Western fronts to converge.17 The Italian campaign had shown how well the Germans used mountainous terrain, and

it made much more sense for the Nazi government to make its last stand

there than in Berlin. Some Nazi leaders had already fled Berlin for

Berchtesgaden, and Hitler himself still planned to leave on 20 April.18

The swing to the east would be primarily an American operation to

destroy German units while avoiding a collision with the Russians further north. The prospect of a collision was worrisome to Marshall as well

as to Eisenhower. On the twenty-seventh Eisenhower considered Marshall's advice to push eastward along a broad front. Marshall also raised

concern about "unfortunate incidents" involving the "advancing forces."

One possible way to minimize the danger, Marshall suggested, was "an

agreed line of demarcation."19

There had been no agreement at Yalta on where each army would

stop, posing the risk of accidental conflict by soldiers who might shoot

first and identify later. In Yugoslavia the previous November, American

fighter planes had mistakenly killed several Russian soldiers and angered

their government.20 The risk became greater as the two armies came

closer.

By April of 1945 Allied and Russian aircraft had fired on each other

over Germany with no damage. Eisenhower tried to prevent similar incidents on the ground by arranging identification signals with the Russians

as well as by halting at the Elbe. "It didn't seem to be good sense," he

recounted after the war, "to try, both of us, to throw our forces toward

Berlin and get mixed up-two armies that couldn't talk the same language, couldn't even communicate with each other. It would have been

a terrible mess."'21

The Soviet military expert David Glantz recently described what a

mess it could have been as part of the forthcoming book A Different War

dealing with the "what ifs" of World War II. In "Allied Drive to Berlin,

April 1945," he described what might well have happened had Truman

ordered Eisenhower to take Berlin. By shifting forces from the Harz

Mountains and the Ruhr he could begin the drive with about twenty divisions while adding another ten within a week. Glantz concluded that

17. MacDonald,Last Offensive, 409.

18. Ambrose, Supreme Commander, 622-23; Tony Le Tissier, The Battle Qf

Berlin (London: St. Martin'sPress, 1988), 80.

19. Chandler, ed., Papers of Dwight David Eisenhower, 4: 2364-65; Ambrose,

Supreme Commander, 628.

20. MacDonald,Last Offensive, 444.

21. James Nelson, ed., General Eisenhower on the Military Churchill:A Conversation with Alistair Cook (New York:Norton, 1970), 55-56; Theodore Draper,"Eisenhower's War:The Final Crisis,"New YorkReview of Books 33 (23 October 1986): 61.

MILITARY

HISTORY

141

DONALDE. SHEPARDSON

both the Allies and the Russians would have fought their way inside

Berlin. In doing so there would have been skirmishes with each other. It

would also have led to an immediate Cold War with the Russians before

the end of the Pacific war.22Colonel Glantz also elaborated on the theme

he and Jonathan House stressed in their When Titans Clashed. The Russians believed, with considerable justification, that they had a "blood

right" to take Berlin. The Soviet Union had sacrificed millions in first

holding, and then driving back the Germans. Taking Berlin was the culmination of its effort as well as the symbol of victory. It would not be

denied the prize by perfidious allies. This emotional preoccupation,

wrote Glantz and House, "drove the Red Army forward toward Berlin."23

The change in military fortune following the Rhine crossing placed

added strain on the Grand Alliance. In Moscow, the Remagen crossing

appeared to be a German attempt to facilitate an Anglo-American

advance to Berlin. The Soviets hardly had time to digest the news of

Remagen before being given indications of another "deal" between Hitler

and the West. On 12 March the American Ambassador to Moscow,

W. Averell Harriman, told the Soviet Commissar for Foreign Affairs,

Vyacheslav Molotov, of secret contacts going on in Berne between the

Allies and representatives of Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, the German Commander in Italy.24

It appeared as though the hopes of Yalta were foundering. Soviet suspicions of the West were reciprocated by Western anger over heavyhanded Soviet actions in Poland. Deteriorating relations spilled over into

the coming conference in San Francisco on the United Nations. On 23

March, Moscow announced that Andrei Gromyko would head the Soviet

delegation to San Francisco. The absence of Molotov indicated a decreasing Soviet interest in the new organization as well as a general chilling of

relations within the Grand Alliance.

After hearing from Marshall, Eisenhower decided he could best

destroy the German army by moving north to Kassel in Westphalia, and

then drive east toward Dresden to meet the Russians. On 28 March he

informed Stalin of his plan to strike toward Leipzig and Dresden. "Could

you," he asked, "therefore, tell me your intentions....

I regard it as

essential that we coordinate our action and make every effort to perfect

the liaison between our advancing forces."25

22. David M. Glantz, "Allied Drive to Berlin, April 1945," A Different War

(Chicago, 1996), 118-82.

23. Glantz and House, When Titans Clashed, 256.

24. Rudy Abramson, Spanning The Century: The Life of W Averell Harriman,

1896-1986 (New York:Morrow,1992), 392.

25. Chandler, ed., Papers of Dwight David Eisenhower, 4: 2531; David Eisenhower, Eisenhower at War,1943-1945 (New York:Random House, 1986), 740-46.

142

THE JOURNAL OF

The Fall of Berlin and the Rise of a Myth

Eisenhower's decision along with his message infuriated the British

who still believed the final thrust would continue north to Berlin.26 He

had communicated directly with Stalin without first consulting with the

Combined Chiefs. Without their consent he had changed the primary

attack to Dresden while leaving Berlin to the Russians. If that were not

enough, he had transferred units from Montgomery's command to General Omar Bradley for the drive on Dresden. The British passed their

objections to Marshall and argued for a strong drive north which would

secure German ports and submarine bases and open the way to Denmark.27

Marshall and the American Joint Chiefs viewed the British note as

just another instance of British carping at Eisenhower, who by now had

demonstrated his ability and his judgment. Churchill himself had gone

to Eisenhower directly on many occasions without consulting the Combined Chiefs. Perhaps Eisenhower might have written to his Soviet counterpart, Marshall Aleksei Antonov, rather than to Stalin, but since Stalin

was the one who mattered, it saved time to go directly to him.

Marshall agreed that the swing to Dresden was the best way to divide

Germany and destroy what remained of the Wehrmacht. With Marshall's

support Eisenhower held to his plan on military grounds, but on 30

March Churchill interjected a political argument for taking Berlin. "If the

enemy resistance should weaken ... why should we not cross the Elbe

and advance as far eastward as possible? This has an important political

bearing, as the Russian army in the south seems certain to enter Vienna

and overrun Austria. If we deliberately leave Berlin to them ... the double event may strengthen their conviction, already apparent, that they

have done everything."28

Eisenhower still believed Dresden should be the primary goal. After

that, he agreed to give some American units back to Montgomery for a

drive to Lubeck in the north that would isolate German troops in Denmark and Norway. His decision was not that of a general who was politically naive. He knew his Clausewitz well enough to understand the

political and psychological importance of capturing Berlin, just as he

understood the importance of liberating Denmark before the Red Army.

Eisenhower also understood the American Constitution and his place

within the Allied command. His actions were subject to the approval of

26. John Ehrman, Grand Strategy, a volume in the series History of the Second

WorldWar(London: HMSO, 1956), 6: 131.

27. Ambrose, Supreme Commander, 633.

28. Winston S. Churchill, Triumph and Tragedy (Boston: Houghton Mifflin,

1953), 463.

MILITARY HISTORY

143

DONALDE. SHEPARDSON

the Combined Chiefs of Staff, Marshall, and ultimately the President of

the United States.

On 7 April Eisenhower told Marshall that "I am the first to admit that

a war is waged in pursuance of political aims, and if the Combined Chiefs

of Staff should decide that the Allied effort to take Berlin outweighs

purely military considerations in the theater, I would cheerfully readjust

my plans and my thinking so as to carry out such an operation. I

urgently believe, however, that the capture of Berlin should be left as

something that we would do if feasible and practicable as we proceed on

a general plan of (a) dividing the German forces by a major thrust in the

middle, (b) anchoring our left firmly in the Lubeck [sic] area and (c)

attempting to disrupt any German effort to establish a fortress in the

southern mountains."29

Eisenhower's primary goal, as well as that of Marshall and Roosevelt,

remained that of defeating Germany quickly with minimum casualties

before deploying forces to the Pacific. By the spring of 1945 these goals

became even more important because of a growing manpower shortage

that was aggravated by congressional objections to using eighteen-yearolds in combat.30

The situation in the Pacific was grim. The future looked even worse.

The atomic bomb was a theory to be tested; fighting the Japanese was a

reality to be dreaded. When the fighting ended on Iwo Jima on 16 March

the U.S. Marine Corps had suffered 25,000 casualties with over 6,000

dead.31 The Philippines campaign had been costlier still, and was not yet

completed.

Operation Iceberg, the invasion of Okinawa, began on 1 April and

encountered fanatical resistance in the south. At sea, Japanese defenders employed Kamikaze attacks in force against American ships, adding

to the carnage. When it finally ended in June, 75,000 American soldiers

and sailors had been killed or wounded. Losses in material were staggering, with 38 ships sunk, another 368 damaged, and over 700 aircraft

lost.32

Following the Yalta conference, the War Department formulated

plans for the final assault on Japan. Operation Olympic, the invasion of

29. Ambrose, Supreme Commander, 642; Chandler, ed., Papers of Dwight David

Eisenhower, 4: 2592.

30. Forrest Pogue, George C. Marshall, 4 vols. (New York: Viking, 1973), 3:

495-99.

31. George W. Garand and Truman R. Strobridge, History of the U.S. Marine

Corps Operations in World WarII (Washington:GPO, 1971), 4: 711.

32. Weinberg,A Worldat Arms, 882; Roy E. Appleman et al., Okinawa: The Last

Battle, a volume in the series United States Army in WorldWarII (Washington:GPO,

1948), 473.

144

THE JOURNAL OF

The Fall of Berlin and the Rise of a Myth

Kyushu, was scheduled for December 1945. Operation Coronet, the

invasion of Honshu, would follow in April 1946. Both operations, and

especially Coronet, depended on transferring men and material from

Europe. Approximately 400,000 Army Air Forces, Army Ground Forces,

and Army Security Forces were scheduled for direct transfer from

Europe to the Pacific from September 1945 to April 1946, with another

400,000 allowed a delay en route in the United States, with all projections subject to available shipping.33

Conquest of the Home Islands might take until the end of the year,

still leaving the Japanese in control of Burma, Formosa (Taiwan),

Manchuria, and large parts of China. The Kwantung army in China and

Manchuria had lost much of its strength, but still had a million men. For

those Americans who survived Okinawa, as well as those who joined

them later, "The Golden Gate in '48" might be the best they could hope

for.34

Allied leaders also had to contend with public opinion and the

fatigue of war. On 3 April, Montgomery complained that public opinion

might affect conduct of the war.35Here he shared a common frustration

with the Americans. A month earlier Marshall had informed Eisenhower

of his own troubles with Congress and public opinion. "Making war in a

democracy," he wrote, "is not a bed of roses."36Both men were right, but

Marshall, more than Montgomery, had learned that generals, presidents,

and prime ministers have to live with it.

In the spring of 1945, Britain was weary after six years of fighting.

Having sacrificed so much for so long, the British people wished to heal

and rebuild, but remained resolved to finish the war against Japan. New

armies were now being formed from throughout the Empire for Operation Zipper, the reconquest of Singapore in December, after which they

were scheduled to join the United States for Operation Coronet.37

It is doubtful whether Churchill could have challenged the Yalta settlement for Germany without destroying his own government. Churchill

had formed a coalition government with the Labour Party of Clement

33. Robert W. Coakley and Richard M. Leighton, Global Logistics and Strategy,

1943-1945, a volume in the series United States Army in WorldWar II (Washington:

GPO, 1968), 585-86; Thomas B. Allen and Norman Polmar, Code Name Downfall:

The Secret Plan To Invade Japan-and Why Truman Dropped the Bomb (New York:

Simon and Schuster, 1995), 145.

34. MartinGilbert, The Second WorldWar:A Complete History (New York:Henry

Holt, 1989), 658.

35. Arthur Bryant, 7TrumphIn The West (New York:Garden City, N.Y.:Doubleday, 1959), 341; Alistair Home and David Montgomery,Monty: The Lonely Leader,

1944-1945 (New York:HarperCollins,1994), 321.

36. Pogue, Marshall, 3: 552.

37. Ehrman, Grand Strategy, 6: 264-67.

MILITARY

HISTORY

145

DONALDE. SHEPARDSON

Attlee in May of 1940. The tensions of war and Churchill's autocratic

style had strained the coalition, and most expected it to end following

the defeat of Hitler. Nevertheless, Attlee had remained a loyal Deputy

Prime Minister and had supported Churchill's decisions at Yalta during a

heated debate in the House of Commons on 1 March.38 Many within

Labour, including the future Foreign Secretary, Ernest Bevin, urged

Attlee to move toward a more independent and "socialist" foreign policy.39 Attlee and Labour would never have supported a confrontation

with the Soviets over Berlin, and any attempt to force one would have

ended the coalition.

Labour had gained in popularity partly because it had developed a

program for domestic reform following the war. It had also benefitted

from an enhanced image of the Soviet Union. Prior to the war Labour

had suffered because of its perceived kinship and sympathy with the

communism of the Soviet Union. The wartime alliance, however, had

done much to transform Stalin from the Red Tyrant of the 1930s into the

national leader of a gallant ally. There was simply too much good will

toward the Soviets to permit a sudden confrontation in the spring of

1945, and the residue of this good will helped Attlee to defeat Churchill

in the July 1945 elections.

The United States was in its fourth year of war. It had not suffered as

its allies had, but the cost was mounting. It was valid to wonder whether

either the American or British public would support bloody "cleaning

up" operations for years to come on the Asian mainland. The Americans

and the British had good reason for avoiding conflict with the Soviet

Union at a time when they were counting on a common effort against

Japan.40

The American people also had come to admire their Russian ally.

The 4 January 1943 lTme featured Stalin as its "Man of the Year"with a

picture of the determined leader beneath which the caption read "All

that Hitler could give, he took-for a second time." The award reflected

American admiration for the sacrifice the Russians had endured, an

admiration that continued until the end of the European war. To suddenly transform a gallant ally into an enemy might have been possible in

Big Brother's Oceania in 1984. It could not have happened in King

George's Britain or President Truman's America in the spring of 1945,

short of an obvious attack on American or British forces.

President Roosevelt's death on 12 April overshadowed conduct of the

war and the strains on the Grand Alliance. In Moscow, Molotov came

immediately to the American embassy to pay his respects. According to

38. The Times, 2 March 1945, 4, 8.

39. Kenneth Harris,Attlee (New York:Norton, 1982), 246.

40. Weinberg,A WorldAt Arms, 843.

146

THE JOURNAL OF

The Fall of Berlin and the Rise of a Myth

Harriman, he seemed genuinely moved by the news. The following day

Stalin displayed similar compassion and sympathy. Stalin obviously was

concerned about the impact of new President Harry Truman on American policy, but he also seemed saddened personally as well.41Whether as

a gesture to Allied solidarity or to the memory of Roosevelt personally,

Stalin agreed when Harriman asked him to send Molotov to San Francisco.42

News of Roosevelt's death was fodder for the faithful in Berlin. In

November the advance of the Red Army had forced Hitler to abandon the

Wolfsschanze in East Prussia and return to a specially constructed

bunker beneath the Reich Chancellery in the center of Berlin. Here he

and his entourage lived in a twilight world where hope and fantasy combined to obscure the reality above.

In September 1936, the former British Prime Minister, David Lloyd

George had agreed with Hitler that Germany had surrendered at "five

minutes to twelve" in 1918. If Germany had held on, the British and

French would have buckled from exhaustion. In this war Hitler was

determined to fight until "five minutes after twelve" and emerge victorious.43

Hitler had convinced himself that 1945 was merely year five in

another Seven Years' War. Defeat could be delayed until the Allied coalition fell into ruin and new weapons were developed to win an ultimate

victory, if German willpower were strong enough. Since the outbreak of

the war, Hitler had increasingly identified himself with Frederick the

Great. "The miracle of the house of Brandenburg," the death of Tsarina

Elizabeth in 1762, had ended the coalition with Austria and France, saving Frederick and leading to the greatness of Prussia. For a brief moment,

Hitler believed that Providence again had intervened and that he and

Germany would be saved.44

By the end of March, however, Allied armies had crossed the Rhine

all along the front. On the left, Montgomery's army swept past the Ruhr

toward the Baltic, while to his right American forces passed the Ruhr and

then turned left to meet their British Allies. Now the heart of German

industry was isolated along with nearly twenty divisions under Field Marshal Model. The Germans held out against the Allied siege until 18 April

when over 300,000 surrendered.45

41. Vojtech Mastny,Russia's Road to the Cold War:Diplomacy, Warfare,and the

Politics of Communism, 1941-1945 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1979),

271.

42. Abramson, Harriman, 394.

43. Donald McCormich,The Mask of Merlin:A Critical Biography of David Lloyd

George (New York:Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1964), 274-75.

44. Bullock, Parallel Lives, 885.

45. MacDonald,Last Offensive, 344-72.

MILITARI HISTORY

147

DONALDE. SHEPARDSON

Eisenhower's final decision to halt at the Elbe came on 14 April, at a

time when American units had entered the Soviet zone and were fifty

miles from Berlin. Lieutenant General William Simpson's Ninth Army

had reached the Elbe on the eleventh after covering 120 miles in ten

days. Simpson believed he could reach Berlin before the Red Army and

wanted to try. According to John Toland, Simpson's forces would attack

"straight down the autobahn to Berlin." There would be little opposition

until the Americans reached the outskirts of the city. "Simpson's claim,"

Toland wrote, "that he could get there in twenty-four hours was not just

boasting. Except for isolated German units-and most of them would

offer little or no resistance-there was nothing between him and Hitler

except Eisenhower."46 Simpson's view also is recounted in Cornelius

Ryan's The Last Battle.47

S.L.A. Marshall disagreed with Ryan and Toland when he reviewed

both their books for the New York 7imes Book Review. "I must," he

wrote, "still say with Virgil: 'These things I saw and part of them I was.'

On the day the halt came ... I was across the Elbe at Barby. German pressure against that bridgehead was still intense." American forces, Marshall

continued, were "spread out .. ., beset on both flanks with a real fire-fight

going up front. Its logistical problems were heavy. Time was needed for

collection and regrouping.... Those were not 50 soft miles from the Elbe

to Berlin; they were long, hard miles, and troops do run out of wind."48

Theodore Draper also was there. "On the front of my own 84th infantry

division, which would have been assigned the mission to Berlin, an estimated 200 Germans with their backs to the river fought bitterly on 21

April five days after our leading elements had reached the Elbe, and three

companies had to be used to deal with them."49Those who were on the

line believed there was plenty between Simpson and Hitler.

Toland's view seems to assume that an Anglo-American drive to

Hitler's bunker would have gone nearly uncontested. The 50,000 German soldiers blocking the Ninth Army were far from the old Wehrmacht,

but they were about equal in number to the force Simpson could have

thrown against them. Any force driving for Berlin from the west would

have to be strengthened by units from the south, would expose its flanks

to attack, and have to traverse the marshy ground west of the city.50Most

likely, German soldiers would fight neither as hard or long as their com46. John Toland, The Last 100 Days (New York:Random House, 1966), 385-86.

47. Cornelius Ryan, The Last Battle (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1966),

330-31.

48. S. L. A. Marshall,"Berlin,April, 1945," New YorkTimes Book Review 71 (27

March 1966): 32.

49. Theodore Draper,"Eisenhower'sWar:The Final Crisis,"New YorkReview of

Books 33 (23 October 1986): 61.

50. Eisenhower, Eisenhower at War, 727.

148

THE JOURNAL OF

The Fall of Berlin and the Rise of a Myth

rades in the East, but many were still willing to defend Hitler and his capital and to shoot or hang comrades who were not.51 Fighting in the streets

of Berlin and its suburbs would be costly as well as long, and any AngloAmerican force in Berlin would have been easily surrounded and isolated

by the oncoming Red Army.52

When asked to estimate the cost in men of a final drive for Berlin

from the Elbe, Bradley had put the figure at one hundred thousand casualties. Eisenhower's concern for casualties was shared by Marshall in

Washington. It was primarily humane, but beyond that there lay the

hard reality that men and material needed in Asia were not to be squandered in Europe. Taking Berlin, Bradley added, was "a pretty stiff price

to pay for a prestige objective, especially when we've got to fall back and

let the other fellow take over."53

And the other fellow meant to have it. Stalin and the Soviet High

Command had been planning for the assault since February, and were

ready to move. "So who will take Berlin, us or the Allies?" Stalin asked

his generals on 1 April. "We will take Berlin," Konev answered, "and take

it before the Allies."54

In February the Red Army had stood at the Oder in a far better position to reach Berlin before the Anglo-Americans. Stalin and the field

commanders had decided to pause in order to eliminate pockets of German forces in the rear and on the flanks before launching any new attack

westward. Supply lines also had been stretched to the limit because

many of the bridges over the Vistula had been destroyed during the

advance.55

Following the defeat in the Ardennes, Hitler had transferred troops

to the east to meet the Russians, slowing progress along the front and

forcing the diversion of men and equipment away from the Berlin thrust

to other areas. In the southeast, Marshal Rodion Malinovsky's Second

and Marshal Feodor Tolbukhin's Third Ukrainian Fronts encountered

stronger German resistance than they had expected on their drive to

Vienna. By the middle of March, German resistance began to weaken in

Hungary and Czechoslovakia as the Red Army drew closer to Vienna.

While the Red Army slowly broke the German resistance along an arc

51. Stephen E. Ambrose, Eisenhower and Berlin: The Decision to Halt at the Elbe

(New York:Norton, 1986), 93; Anthony Read and David Fisher, The Fall of Berlin

(New York:Norton, 1992), 298.

52. Pogue, Marshall, 3: 575.

53. Omar N. Bradley,A Soldier's Story (New York:Henry Holt and Co., 1951),

535.

54. 0. A. Rzheshevsky, "The Race for Berlin," trans. David M. Glantz, Journal of

Slavic Military Studies 8 (September 1995): 569.

55. Georgi Zhukov, The Memoirs of Marshal Zhukov (New York: Delacorte,

1971), 580.

MILITARY HISTORY

149

DONALDE. SHEPARDSON

from Vienna northward, Eisenhower's forces were rapidly driving into

Germany.

The speed of the Western advance and the secret peace talks in

Berne were sufficient to revive Stalin's distrust of his allies and to make

him wonder whether they would deprive him of Berlin. Eisenhower had

tried to allay Soviet concern in his message to Stalin on 28 March, and

to a point he did. Stalin knew, however, that Eisenhower was subject to

pressure from above, and he feared that the British would force Eisenhower to take Berlin.56 There was always the possibility that Eisenhower's announced intention to move east was merely a feint to cover

the major drive for Berlin. Whatever Stalin's fears and motives, he apparently believed the Germans were negotiating with the British to turn

over Berlin before it could be captured by the Red Army.57

Before replying to Eisenhower, Stalin summoned Zhukov and Konev

to Moscow to develop a plan for launching an offensive on 16 April that

would capture Berlin by the end of the month and take the Red Army to

the Elbe to secure the occupation zone assigned to the Soviet Union at

Yalta.58 In his message to Eisenhower, Stalin agreed that Berlin was no

longer important. He promised that the main blow of the Soviet offensive

would begin around the middle of May, and that it would head for a Dresden-Leipzig rendezvous with Eisenhower's forces.59

The Red Army made its swiftest redeployment of the war for the

attack. It was an awesome force of 2.5 million men, 20 armies, 150 divisions, 6,000 tanks, 7,500 aircraft, 41,000 artillery pieces and mortars,

3,000 rocket launchers, and nearly 100,000 motor vehicles.60 In contrast

to Anglo-American troops on the Elbe, it was well supplied and "gassed

up."7

It had an awesome task. Berlin, Zhukov later recounted, had a "total

area of almost 350 square miles. Its subway and other widespread underground engineering networks provided ample possibilities for troop

movements. The city itself and its suburbs had been carefully prepared

for defense. Every street, every square, every alley, building, canal and

bridge represented an element in the city's defense system."'6'

56. Le Tissier, Zhukov at the Oder, 107.

57. Erickson, Road to Berlin, 528; Zhukov,Memoirs, 580-81.

58. Zhukov, Memoirs, 531-33; Ziemke, Stalingrad to Berlin, 470-71; Read and

Fisher, Fall of Berlin, 280-83.

59. Ziemke, Stalingrad ToBerlin, 467.

60. Cartier,Der zweite Weltkrieg, 994; Glantz and House, When Titans Clashed,

261; Ziemke, Stalingrad to Berlin, 470.

61. Georgi K. Zhukov, Marshal Zhukov's Greatest Battles, trans. Theodore

Shabad (New York:Harper and Row, 1969), 284. Zhukov'sestimate of Berlin's size is

accurate. The metropolitan area was approximately 340 square miles. Its population

had fallen from approximately 4,500,000 in 1942 to just under 3,000,000 by the end

150

THE JOURNAL OF

The Fall of Berlin and the Rise of a Myth

Zhukov assigned command of the First Byelorussian Front to General Vasili Sokolovsky in order to supervise the entire offensive.

Sokolovsky was assigned to lead the primary drive with support from

Konstantin Rokossovski's Second Byelorussian Front in the north and

Konev's First Ukrainian Front in the south.

Hitler issued his last directive on 15 April. With determination, he

said, German soldiers could defeat the invader and gain "a turning point

in the war."62But it was too late for turning points. The forty miles

between Berlin and the Red Army was defended by thirty-five divisions

of varied strength and equipment. The Russians now commanded such

overwhelming superiority that blunders could not prevent their victory.

On 16 April, the First Byelorussian and First Ukrainian Fronts

attacked before dawn in an attempt to surprise the Germans while blinding them with searchlights. The initial assault failed, but the Red Army

pressed on in spite of terrible casualties, as it had throughout the war.63

By the nineteenth Russian superiority began to dominate. Sokolovsky's

Byelorussian Front advanced, but more slowly than Zhukov had

intended. He ordered Rokossovsky to swing southwest instead of northwest to ensure encirclement, in case the main drive on the city failed.

Progress in the center and the north was also slower than Stalin wanted.

Zhukov ordered Konev to accelerate his drive from the southeast across

the Spree River. By the twentieth the battle for Berlin was decided. Russian soldiers entered the city and were fighting their way to the center

street by street, while other forces advanced to encircle the city.64

Officials in the bunker advised Hitler to leave immediately to join

German forces in the south, but he delayed. That night most of his

entourage fled southward. On the twenty-first, Hitler ordered SS General

Felix Steiner to attack from the southern suburbs of Berlin with all available troops. "Any commander," Hitler yelled at Luftwaffe General Karl

Koller, "who holds back his forces will forfeit his life in five hours."65 In

the confusion, Steiner never attacked while the withdrawal of other

forces only enabled the Russians to advance further.

of the war (Burkhard Hofmeister, Berlin [Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1975], 50); Le Tissier, Battle of Berlin, 15-24.

62. Hitler's Weisungen fuir die Kriegfiihrung, 1939-1945: Dokumente des

Oberkommandos der Wehrmacht, Herausgegeben von Walther Hubatsch (Frankfurt

am Main:Bernard und Graefe Verlag fuirWehrwessen, 1962), 310-11.

63. Glantz and House, When litans Clash, 263; Le Tissier, Zhukov at the Oder,

159.

64. Cartier,Der zweite Weltkrieg,993-95; Seaton, Russo-German War, 572-76.

65. Karl Koller,Der letzte Monat: Die Tagebuchaufzeichnungen das ehemaligen

Chefs des Generalstabes der deutschen Luftwaffe vom 14. April bis zum 27. Mai

1945 (Mannheim: N. Wohlgemuth, 1949), 23.

MILITARY HISTORY

151

DONALDE. SHEPARDSON

Hitler flew into a rage of self-pity when he learned there had been no

attack. He had been betrayed and deserted by those he had trusted. To

punish them he would now abandon them to their fate. He would lead no

last defense from Berchtesgaden. He would die in Berlin.66 Hitler's decision further confused what remained of German defenses. Hermann

Goring's attempt to contact Hitler regarding the succession was seen as

treason. Reports of Heinrich Himmler's meeting with Swedish diplomats

seemed worse, since Himmler had been one of Hitler's most loyal followers. By the twenty-ninth, as Russian troops were closing in on the

Chancellery, Hitler made final preparations for his death and the disposal of his body. The following afternoon he and his new bride, Eva

Braun, killed themselves.

For a time Martin Bormann and Goebbels tried to conceal Hitler's

death, although they notified the stunned Admiral Karl Donitz that he

had been named Hitler's successor. Bormann wanted to join Donitz in

the north and take his position in his new government, but he could not

as long as the Russians had the city encircled. Early in the morning of 1

May they sent General Hans Krebs to negotiate a cease fire with Marshal

Vasili Chuikov, the defender of Stalingrad, who was directing the final

assault. Chuikov and Zhukov were in no mood to grant an armistice or

to sign a separate surrender and sent Krebs back to the bunker with no

terms except unconditional surrender.67 Upon hearing the news, Bormann tried unsuccessfully to escape from the city and join Donitz, while

Goebbels and his wife chose suicide after killing their children. Krebs

decided to shoot himself. At 0600 hours on 2 May Lieutenant General

Helmuth Weidling surrendered along with roughly 100,000 men.68

Hitler's death was more instrumental in ending the war than the fall

of Berlin. All oaths to continue were invalid and all faith in victory gone.

At Flensburg near the Danish border Donitz hoped to gain time for German civilians and soldiers to flee westward. Eisenhower finally issued an

ultimatum: either surrender unconditionally or he would close the border with the Soviet zone. Donitz labeled Eisenhower's ultimatum "extortion," but realized that there was no alternative. At 0241, 7 May, General

Alfred Jodl signed the unconditional surrender.69

Victory in Europe brought somber reflection as well as joy. "Across

that large, blood-drenched swath of Europe," remembered Omar

66. Bullock, Parallel Lives, 887.

67. Vasili I. Chuikov, The Fall of Berlin, trans. Ruth Kisch (New York:Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1967), 213ff; Le Tissier, Berlin, 207-8.

68. The Soviets claimed to have taken 130,000 prisoners, a figure which may

have included civilians for labor camps in the Soviet Union; Le Tissier, Battle of

Berlin, 224.

69. Pogue, Supreme Command, 485-90; Walter Ludde-Neurath, Regierung

Donitz (Gottingen: Musterschmidt, 1964), 68-70.

152

THE JOURNAL OF

The Fall of Berlin and the Rise of a Myth

to rise no more. The

Bradley, "586,628 soldiers had fallen-135,576

grim figures haunted me. I could hear the cries of the wounded, smell the

stench of death. I could not sleep; I closed my eyes and thanked God for

victory."70

On V-E Day Stalin held Berlin. It had cost him nearly 80,000 dead or

missing, with another 280,000 wounded, 2,000 artillery pieces

destroyed, and over 900 aircraft lost.71 He still had the firepower to keep

it. But Stalin also had a war in Asia to fight. The Red Army now had to

make a massive shift of men and material for the attack into Manchuria

in August. It was no time to challenge his allies in Berlin. In July, American, British, and French forces took possession of their zones.

The Red Army had paid a frightful price for Berlin and now they

were giving half of it to allies who had paid nothing. Here was a gift. For

the next forty-five years, those Western zones embarrassed, irritated,

and threatened Stalin and his heirs. During the years that followed

Zhukov was criticized for his timidity in February of 1945. In March

1964, Chuikov publicly stated that "Berlin would have been taken in

about ten days," had Zhukov shown more courage in dealing with

Stalin.72 Zhukov responded by defending his decision, and his supporters continue to do so. Others, however, support Chuikov and wonder

how much better things might have been, had Zhukov and Stalin been

more realistic in the spring of 1945.73

70. Omar Bradley and Clay Blair,A General's Life: An Autobiography (New York:

Simon and Schuster, 1983), 436.

71. Glantz and House, When Titans Clashed, 269, 375.

72. Chuikov, The Fall of Berlin, 119.

73. Zhukov, Greatest Battles, 275; Glantz and House, When Titans Clashed,

370 n.32.

MILITARY HISTORY

153

154

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5795)

- Get Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: LibraryDocumento2 pagineGet Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: LibraryMariella GiorginiNessuna valutazione finora

- Get Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: LibraryDocumento2 pagineGet Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: LibraryMariella GiorginiNessuna valutazione finora

- Get Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: LibraryDocumento2 pagineGet Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: LibraryMariella GiorginiNessuna valutazione finora

- Get Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: Panzer SchlachtDocumento2 pagineGet Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: Panzer SchlachtMariella GiorginiNessuna valutazione finora

- Get Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: LibraryDocumento2 pagineGet Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: LibraryMariella GiorginiNessuna valutazione finora

- Get Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: LibraryDocumento2 pagineGet Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: LibraryMariella GiorginiNessuna valutazione finora

- Get Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: LibraryDocumento2 pagineGet Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: LibraryMariella GiorginiNessuna valutazione finora

- Get Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: in Colour 01 To The Last BulletDocumento2 pagineGet Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: in Colour 01 To The Last BulletMariella GiorginiNessuna valutazione finora

- Get Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: Under The Gun 03 WestwallDocumento2 pagineGet Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: Under The Gun 03 WestwallMariella GiorginiNessuna valutazione finora

- Get Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: Under The Gun 01 Panzers in The BocagelDocumento2 pagineGet Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: Under The Gun 01 Panzers in The BocagelMariella GiorginiNessuna valutazione finora

- Glantz David & House - When Titans ClashedDocumento222 pagineGlantz David & House - When Titans Clashedbror82% (17)

- Get Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: LibraryDocumento2 pagineGet Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: LibraryMariella GiorginiNessuna valutazione finora

- Get Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: Firefly Collection 01Documento2 pagineGet Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: Firefly Collection 01Mariella GiorginiNessuna valutazione finora

- Get Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: Das III Reich Sondersheft 06 Das Heer in Der Deutschen Wehrmacht 1939 1945Documento2 pagineGet Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: Das III Reich Sondersheft 06 Das Heer in Der Deutschen Wehrmacht 1939 1945Mariella GiorginiNessuna valutazione finora

- Get Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: German Army Handbook 1939 45Documento2 pagineGet Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: German Army Handbook 1939 45Mariella GiorginiNessuna valutazione finora

- Get Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: Concord Publication 6514 Waffen SS at War 1 The Early Years 1939 42Documento2 pagineGet Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: Concord Publication 6514 Waffen SS at War 1 The Early Years 1939 42Mariella GiorginiNessuna valutazione finora

- Get Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: Concord Publication 6534 Into The CauldronDocumento2 pagineGet Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: Concord Publication 6534 Into The CauldronMariella GiorginiNessuna valutazione finora

- Get Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: Militaria 06 Waffen SS Cz.2Documento2 pagineGet Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: Militaria 06 Waffen SS Cz.2Mariella GiorginiNessuna valutazione finora

- Get Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: Concord Publication 6506 March of The Deaths Head DivisionDocumento2 pagineGet Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: Concord Publication 6506 March of The Deaths Head DivisionMariella GiorginiNessuna valutazione finora

- Get Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: Concord Publication 6515 Waffen SS at War 2 The Late Years 1943 44Documento2 pagineGet Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: Concord Publication 6515 Waffen SS at War 2 The Late Years 1943 44Mariella GiorginiNessuna valutazione finora

- Get Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: Fighting Techniques of The Panzer Grenadier 1941 45Documento2 pagineGet Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: Fighting Techniques of The Panzer Grenadier 1941 45Mariella GiorginiNessuna valutazione finora

- Get Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: Fighting Techniques of The Panzer Grenadier 1941 45Documento2 pagineGet Unlimited Downloads With A Membership: Fighting Techniques of The Panzer Grenadier 1941 45Mariella GiorginiNessuna valutazione finora

- Archaeology Viking Shield From ArchaeologyDocumento20 pagineArchaeology Viking Shield From ArchaeologyMariella Giorgini50% (2)

- Viking Language Old Norse Brochure Byock-LibreDocumento2 pagineViking Language Old Norse Brochure Byock-LibreMariella Giorgini0% (1)

- Skull BonesDocumento29 pagineSkull BonesMariella GiorginiNessuna valutazione finora

- Imagining An Early OdinDocumento14 pagineImagining An Early OdinMariella GiorginiNessuna valutazione finora

- COMPUTUS RUNICUS The Runic Calender From Gotland From 1328. Described by Ole WormDocumento16 pagineCOMPUTUS RUNICUS The Runic Calender From Gotland From 1328. Described by Ole WormMariella GiorginiNessuna valutazione finora

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- The Troll's TuskDocumento3 pagineThe Troll's TuskJames YuNessuna valutazione finora

- Arg Essay DronesDocumento4 pagineArg Essay Dronesapi-242360883Nessuna valutazione finora

- Synopsis by WambeckDocumento671 pagineSynopsis by WambeckSteve Ubiam100% (3)

- The Causes of The Crimean WarDocumento4 pagineThe Causes of The Crimean Warapi-295776078Nessuna valutazione finora

- CSS Essay - Free Speech Should Have LimitationsDocumento4 pagineCSS Essay - Free Speech Should Have LimitationsAnaya Rana100% (1)

- Ethnic Autonomy in The Soviet Union: Teresa Rakowska-HarmstoneDocumento2 pagineEthnic Autonomy in The Soviet Union: Teresa Rakowska-HarmstoneMachos MachosNessuna valutazione finora

- GEOPOLITICS101Documento3 pagineGEOPOLITICS101Adolf HitlerNessuna valutazione finora

- Facts: 30,000 Women Raped in The Bosnian GenocideDocumento2 pagineFacts: 30,000 Women Raped in The Bosnian GenocideBosnian Muslims and JewsNessuna valutazione finora

- Army Roster, Blank, 8th EdDocumento3 pagineArmy Roster, Blank, 8th EdChad Alan NicholsNessuna valutazione finora

- Napoleon BonaparteDocumento7 pagineNapoleon Bonapartefnkychic3767% (3)

- KAYNDocumento3 pagineKAYNAlvin BindedNessuna valutazione finora

- History of RotcDocumento2 pagineHistory of RotcKenzii LopezNessuna valutazione finora

- Peteris Stucka Pyotr Ivanovich Stuchka Robert Sharlet, Peter B MaggsDocumento288 paginePeteris Stucka Pyotr Ivanovich Stuchka Robert Sharlet, Peter B MaggsNatko NemecNessuna valutazione finora

- Library Aviation Quiz PDFDocumento1 paginaLibrary Aviation Quiz PDFRajesh VasagarNessuna valutazione finora

- Case of Kian Delos SantosDocumento6 pagineCase of Kian Delos SantosYeager GaryNessuna valutazione finora

- Arrelano Letter To PNPDocumento1 paginaArrelano Letter To PNPPatrio Jr SeñeresNessuna valutazione finora

- Cornplanter Speech To George WashingtonDocumento2 pagineCornplanter Speech To George WashingtonKateNessuna valutazione finora

- Unofficial Third Edition AdaptationDocumento23 pagineUnofficial Third Edition AdaptationChris PattersonNessuna valutazione finora

- Urban Scrawl: Satire As Subversion in Banksy's Graphic DiscourseDocumento76 pagineUrban Scrawl: Satire As Subversion in Banksy's Graphic DiscourseCristobal BianchiNessuna valutazione finora

- Rationalization - 3rd Periodical Exam SS8Documento67 pagineRationalization - 3rd Periodical Exam SS8Venus Christine VillorejoNessuna valutazione finora

- Inquiry2 Evidence1 DoucetteDocumento6 pagineInquiry2 Evidence1 Doucetteapi-314067090Nessuna valutazione finora

- Mujalla Taliban Shumara02Documento90 pagineMujalla Taliban Shumara02UmarNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 To 11Documento11 pagine1 To 11Neha ThakurNessuna valutazione finora

- History of The Redstone Missile SystemDocumento198 pagineHistory of The Redstone Missile SystemVoltaireZeroNessuna valutazione finora

- ΑφιέρωμαDocumento40 pagineΑφιέρωμαEleniDesli100% (2)

- Clea Koff Forensic AnthropologistDocumento3 pagineClea Koff Forensic AnthropologistSydney MacekNessuna valutazione finora

- Reported Speech Key Grade 9Documento9 pagineReported Speech Key Grade 9Trần Anh DũngNessuna valutazione finora

- Analysis of Product Using Reverse EngineeringDocumento6 pagineAnalysis of Product Using Reverse EngineeringManthan PagareNessuna valutazione finora

- Dieci Mini Agri 25 6 Spare Parts Catalog Axl0060Documento22 pagineDieci Mini Agri 25 6 Spare Parts Catalog Axl0060justinkelly041286pbo100% (40)

- Emergence of The Modern State Powerpoint PresentationDocumento12 pagineEmergence of The Modern State Powerpoint PresentationdivadhivyaNessuna valutazione finora