Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Review of Language and The Internet by David Crystal

Caricato da

Slovenian Webclassroom Topic ResourcesTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Review of Language and The Internet by David Crystal

Caricato da

Slovenian Webclassroom Topic ResourcesCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Language Learning & Technology May 2003, Volume 7, Number 2

http://llt.msu.edu/vol7num2/review1/ pp. 24-27

REVIEW OF LANGUAGE AND THE INTERNET

The Biggest Language Revolution Ever Meets Applied Linguistics in the 21st Century

Language and the Internet

David Crystal

2001

ISBN 0 521 80212 1

£15.00

272 pp.

Cambridge University Press

110 Midland Avenue

Port Chester, NY 10573-4930

http://uk.cambridge.org/

Reviewed by Steven L. Thorne, Penn State

That the Internet invokes profound opportunities for language educators and students has been long

discussed (with some of the better examples published in this very journal). In his 2001 book, Language

and the Internet, David Crystal only sporadically mentions educational issues or contexts, but this does

not diminish the importance or relevance of this book for applied linguists. Crystal, a prolific linguist who

has authored numerous scholarly and reference texts on a variety of language related topics, turns his

attention in this volume to the language practices visibly mediated by the Internet. In a personal preface to

the volume, he mentions that as a prominent linguist, he has often been asked about what effect the

Internet has had on language, a question for which he did not have a clear answer. This prompted him to

explore a variety of what he terms "Internet situations," each of which comes to form a chapter in this

272-page volume.

Crystal's linguist-eye perspective is just what language educators need in order to understand the broader

implications of the complex relations governing language-based communication and the Internet as a set

of distinctive modalities. Regrettably, Crystal selects the awkward and overly cute term "Netspeak" to

describe the many forms of language visible on the Internet. His selection of this term clearly arises from

the ephemeral neologisms common to digital culture in the mid and late 1990s, evidence for which

resides in the list of alternatives he considered -- "netlish," "weblish," and "cyberspeak." Though it is a

small critique, this text would be improved should he have selected a less quaint term such as simply

"computer-mediated communication" (CMC) or "electronic discourse." This small problem aside, Crystal

convincingly describes language use and language change within "Internet situations" such as e-mail,

synchronous and asynchronous "chat groups" (his term), virtual worlds (MUDs and MOOs), and the

World Wide Web. Within each Internet situation, he discusses and, where possible, explicates the

development of new graphic conventions such as emoticons and abbreviations, the emergence of novel

genres, Internet-derived neologisms, and features of communicative activity that could only have emerged

through electronic media (e.g., forms of interaction in synchronous chat, pp. 151-167, and "message

intercalation" in e-mail, p. 120.) Below, I review select chapters of this text in greater detail.

Crystal's treatment of e-mail (chapter 3) describes this modality's history, including its fixed discourse

elements (the header structure) and various epistolary conventions which were borrowed from earlier

textual modalities (notes, letters, memos, postcards). Despite its unglamorous everyday quality for regular

users, Crystal reminds the reader that e-mail use emphasizes "clarity of the message on the screen" (p.

110) and has precipitated the now common use of numbered and bulleted lists, a feature rare in earlier

written communication. Unlike the memo that preceded it, e-mail is often used as a tool for dialogue and

Copyright © 2003, ISSN 1094-3501 24

Reviewed by Steven L. Thorne Review of Language and the Internet

can include a string of anterior messages. In this sense, a new document is created as each interaction

builds upon prior messages. Crystal predicts that over time, e-mail will exhibit a "much wider stylistic

range than it does at present, as the medium is adapted to suit a broader range of communicative

purposes" (p. 107). Does this "much wider stylistic range," potentially outside of the norms of

prescriptivist grammatical and orthographic conventions, present a problem rather than an opportunity for

language educators? Crystal responds that e-mail is not a "medium to be feared for its linguistic

irresponsibility (because it allows for radical graphological deviance) but as one which offers a further

domain within which children can develop their ability to consolidate their stylistic intuitions and make

responsible linguistic choices." Addressing language education directly, Crystal argues that "Email has

extended the language's stylistic range in interesting and innovative ways. In my view, it is an

opportunity, not a threat, for language education" (p. 128). I agree with Crystal's optimism and

acknowledgement that the Internet has unquestionably expanded the average range and diversity of

specifically graphical (written) communication. I would also extend this line of reasoning to mention that

Internet situations are no longer optional communicative modalities, nor is the use of Internet

communication tools some sort of proxy or practice environment for subsequent communication in face-

to-face or formal writing contexts. Ever increasingly, everyday communication in work, school, and

interpersonal domains is Internet mediated. Understanding and acquiring new genres of communication

(at the level of style as well as lexicon and register) are critical dimensions of the process of becoming a

competent late-modern communicator.

In chapter 5, Crystal addresses group uses of CMC tools of both the synchronous and asynchronous

varieties. To help substantiate Crystal's assertion that the Internet has kindled the wide-spread use of

bulleted lists, here are the descriptive features Crystal attributes to group CMC use (what he subsumes

under the label synchronous and asynchronous "group chats"):

• These modalities encourage an "I" language variety where personal reference and perspective

dominate.

• "It" is used to introduce personal comments ("it seems to me…").

• Participants frequently use private verbs such as "think," "feel," "know" (describing activity that

cannot be publicly observed).

• Tag or rhetorical questions are used to express personal attitude, views, and to encourage

responses from interlocutors.

• Synchronous and asynchronous tools lack (or differentially render) the face-to-face conventions

of turn-taking, floor-taking, and adjacency pairing, with implications for rate of topic decay,

coherence and cohesion, and simultaneity and overlap of messages.

In reference to the final point and quoting Herring, Crystal acknowledges that CMC environments are

"both dysfunctionally and advantageously incoherent" (p. 169). Though numerous features of Internet

communication have the propensity to drive language prescriptivists mad with rage, and certainly most

everyone has been the producer of an utterance that upon rereading makes us cringe, people adapt

language to meet new needs, new situations, and new modalities. This is the heart of language evolution.

As new digital communication tools become available, genres of communicative practice will develop

that are difficult to predict or possibly even to imagine.

Chapter seven describes language use on the World Wide Web which is "graphically more eclectic than

any domain of written language in the real world" (p. 197) and one that "holds a mirror up to our

linguistic nature, it is a mirror that both distorts and enhances, providing new constraints and

opportunities" (p. 198). In assessing this situation, Crystal suggests that this is because the language of the

Web is under no central control, does not respect national boundaries, and thus spawns new

communicative genres. Due to the Web's dual function of reception (finding texts) and production

(relative ease of producing HTML texts), "people have more power to influence the language of the Web

than in any other medium" (p. 208).

Language Learning & Technology 25

Reviewed by Steven L. Thorne Review of Language and the Internet

In this chapter Crystal also includes an interesting discussion on word processing. In contrast to the

flexible orthography and syntax in many CMC contexts, Crystal rightly points out that word processors

and some e-mail clients "must surely influence our intuitions about the nature of our language" through

the prescriptivist grammar and spell-checkers they include (p. 212). Though certainly useful as indicators

of typos or inadvertent grammar errors, Crystal is of the opinion that

a large number of valuable stylistic distinctions are being endangered by this repeated encounter

with the programmer's prescriptive usage preferences. Online dictionaries and grammars are

likely to influence usage much more than their traditional Fowlerian counterparts ever did. It

would be good to see a greater descriptive realism emerge, paying attention to the sociolinguistic

and stylistic complexity which exists in a language, but at present the recommendations are

arbitrary, oversimplified, and depressingly purist in spirit. (p. 212)

A few pages later, Crystal concludes that "[grammar and spelling] software designers underestimate the

amount of variation there is in the orthographic system, the pervasive nature of language change, and the

influence context has in deciding whether an orthographic feature is obligatory or optional" (p. 214). His

passion to affirm the many language varieties visible over the Internet, and his well-supported arguments

against grammatical and stylistic essentialism, provide language educators with the challenge to be

balanced in their assessment strategies of communication that occurs in digital environments. For

language educators, the Internet provokes the following tension -- to be accepting of creative innovation

while also corrective of language use that may fall too far outside of expert speaker norms.

Crystal also tackles the issue of language diversity and notes that roughly one quarter of the world's

languages have some Internet presence. For languages with few speakers or little telecommunications

infrastructure, he reasonably hypothesizes that "until a critical mass of Internet penetration in a country

builds up, and a corresponding mass of content exists in the local language, the motivation to switch from

English-language sites will be limited to those for whom issues of identity outweigh issues of

information" (p. 220). However, we need not fear total domination by English as the primary medium of

digital communication. Especially through wireless networks that bypass the infrastructural problems

associated with wires and cables, an increasing proportion of the world's population will participate in the

use and production of the Internet. This, Crystal notes, will afford a glimpse at "language presence in a

real sense … sites which allow us to see languages as they are" (pp. 220-221).

In the eighth and final chapter, "The Linguistic Future of the Internet," Crystal surmises that computer

mediated communication may become an obsolete notion as Internet information and communication

functionality migrates to other tools, notably mobile phones and personal digital assistants at the moment,

but also hand held units that will combine Internet access with digital photography and video, fax, and

traditional media like radio and television. He suggests that technology developments will have two broad

impacts: (a) new modalities and their effects on the nature of language and speech community and (b)

new modalities bringing languages and speech communities into contact with one another. As speakers of

distinct language varieties come together for an increasing number of purposes, automated speech

transcription and translation tools will likely improve and become ubiquitous. As noted above, however,

the more commonly spoken languages will likely remain far better served by the private sector services

that will support such development.

Crystal does discuss language education issues in this final chapter and remarks that second language

education and applied linguistics have been leaders in the use of the Internet for specific purposes.

Examples include asynchronous projects at intra- and interclass levels and "key-pal" international

partnerships (the topic of this LLT special issue). Synchronous tools and what Crystal terms "virtual

world" environments (MUDs and MOOs) facilitate real-time communication which may assist with "the

promotion of rapid responses," but cautions that the truncated forms of language found in chat

environments may "represent only a small part of the grammatical repertoire of a language" (p. 235). As

Language Learning & Technology 26

Reviewed by Steven L. Thorne Review of Language and the Internet

mentioned, Crystal also emphasizes the "'authentic materials"' and "'genuine written data"' that is

available via the Web. With all Internet technologies, Crystal warns that it is the teachers who must be

aware of the diversity of Internet speech communities, to know the relation between modalities and

expected genres of communication, and to be familiar with the nomenclature of the Internet itself. Well in

line with the language ideology he reiterates throughout the book, Crystal does not take a prescriptivist

approach and suggests that we embrace language change, including the flexible orthography, grammar,

and style common to the many varieties of "netspeak." However, he also points out that language

educators should be aware of the complex pragmatic competence L2 learners will need to evaluate the

appropriateness of language used on e-mail and chat groups. "The bending and breaking of rules," which

form the heart of ludic behavior, present "a problem to those who have not yet developed a confident

command of the rules per se" (pp. 236-237).

Certain omissions are apparent in the book, but anyone writing about contemporary uses of technology

knows that it presents a moving target. In other words, it is not possible to predict even near-future

technology use with much accuracy. Crystal's book was published in 2001, however, and includes

references from 2000. It is mildly surprising that he does not address what can only be described as the

"Instant Messenger phenomenon." Instant Messenger (IM) has become the leading synchronous CMC

tool for undergraduate populations (see Thorne, 2003) and was tremendously popular even in the late

1990s. Per my experience using this text in applied linguistics courses, non-linguistically focused or

trained individuals have found his prose, linguistic descriptions, and argumentation to be clear and

inspiring. Very usefully, Crystal discusses and takes examples from widely referenced linguistic, CMC,

and Internet Studies research. This aspect of the book should prove useful to foreign and second language

educators who wish to glean a synoptic overview of the vast research on CMC and Internet Studies.

In the final analysis, Language and the Internet is a review text providing a useful and well-referenced

overview of Internet-related research. Commensurate with other books written for such purposes, this

volume provides few new or striking insights to Internet Studies enthusiasts. This said, Crystal has written

an engaging volume that language educators will find practical as they grapple with questions of how

Internet-mediated language may, and perhaps ought to be, different from language use in other

modalities. As such, this book is important for applied linguists who wish to understand the broader

background of language use and language change via the Internet, which he describes as "a linguistic

singularity -- a genuine new medium" (p. 238). Invoking Berners-Lee, the acknowledged developer of the

Internet, Crystal reminds us that the Internet is less a technological fact than a social fact, and "its chief

stock-in-trade is language" (p. 236). Brace yourself, for as Crystal notes, and I concur, "we are on the

brink of the biggest language revolution ever" (p. 241).

ABOUT THE REVIEWER

Steve Thorne is the Associate Director of the Center for Language Acquisition, Associate Director of the

Center for Advanced Language Proficiency Education and Research (CALPER), and Assistant Professor

in Linguistics and Applied Language Studies at Penn State University. His research addresses activity

theory, additional language learning, and computer-mediated communication.

E-mail: sthorne@psu.edu

REFERENCE

Thorne, S. (2003). Artifacts and cultures-of-use in intercultural communication. Language Learning &

Technology, 7(2), 37-66. Available at http://llt.msu.edu/vol7num2/thorne/

Language Learning & Technology 27

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Fallacies Do We Use Them or Commit ThemDocumento21 pagineFallacies Do We Use Them or Commit ThemSlovenian Webclassroom Topic ResourcesNessuna valutazione finora

- Slovene at Foreign Universities - Slovenia - Si, 2020Documento1 paginaSlovene at Foreign Universities - Slovenia - Si, 2020Slovenian Webclassroom Topic ResourcesNessuna valutazione finora

- Crossroads of Anger Tensions and Conflic PDFDocumento18 pagineCrossroads of Anger Tensions and Conflic PDFSlovenianStudyReferencesNessuna valutazione finora

- Slovene Language in Digital Age, Simon Krek, 2012Documento87 pagineSlovene Language in Digital Age, Simon Krek, 2012Slovenian Webclassroom Topic ResourcesNessuna valutazione finora

- Contemporary Legends N SloveniaDocumento2 pagineContemporary Legends N SloveniaSlovenianStudyReferencesNessuna valutazione finora

- D.F.E. Schleiermacher Outlines of The ArDocumento12 pagineD.F.E. Schleiermacher Outlines of The ArSlovenian Webclassroom Topic ResourcesNessuna valutazione finora

- Reciprocity in International Student ExchangeDocumento11 pagineReciprocity in International Student ExchangeSlovenian Webclassroom Topic ResourcesNessuna valutazione finora

- Aspects and Strategies of Tourist Texts TranslationsDocumento41 pagineAspects and Strategies of Tourist Texts TranslationsSlovenian Webclassroom Topic Resources100% (1)

- Seeing The Elephant The Tale of GlobalisationDocumento4 pagineSeeing The Elephant The Tale of GlobalisationSlovenian Webclassroom Topic ResourcesNessuna valutazione finora

- History - Narodna in Univerzitetna Knjižnica 2019Documento1 paginaHistory - Narodna in Univerzitetna Knjižnica 2019Slovenian Webclassroom Topic ResourcesNessuna valutazione finora

- Europe Day 9 May 2020 - EurostatisticsDocumento1 paginaEurope Day 9 May 2020 - EurostatisticsSlovenian Webclassroom Topic ResourcesNessuna valutazione finora

- Database of Translations - JAK RS 2019Documento1 paginaDatabase of Translations - JAK RS 2019Slovenian Webclassroom Topic ResourcesNessuna valutazione finora

- Manuscript, Rare and Old Prints Collection - Narodna in Univerzitetna Knjižnica - Spletna StranDocumento1 paginaManuscript, Rare and Old Prints Collection - Narodna in Univerzitetna Knjižnica - Spletna StranSlovenian Webclassroom Topic ResourcesNessuna valutazione finora

- Slovenia Its Publishing Landscape and Readers, JAK RS, 2019Documento48 pagineSlovenia Its Publishing Landscape and Readers, JAK RS, 2019Slovenian Webclassroom Topic ResourcesNessuna valutazione finora

- Presentation Materials - JAK RS, 2019Documento1 paginaPresentation Materials - JAK RS, 2019Slovenian Webclassroom Topic Resources100% (3)

- Ales Debeljak, Translation, JAK RS, 2017Documento100 pagineAles Debeljak, Translation, JAK RS, 2017Slovenian Webclassroom Topic ResourcesNessuna valutazione finora

- History of The Stud Farm and Lipizzan Horses - LipicaDocumento1 paginaHistory of The Stud Farm and Lipizzan Horses - LipicaSlovenian Webclassroom Topic ResourcesNessuna valutazione finora

- Assassination in Sarajevo - WW 1Documento2 pagineAssassination in Sarajevo - WW 1Slovenian Webclassroom Topic Resources100% (1)

- The Geography of Urban Environmental Protection in SloveniaDocumento1 paginaThe Geography of Urban Environmental Protection in SloveniaSlovenian Webclassroom Topic ResourcesNessuna valutazione finora

- WW1 in Writing - WW 1Documento2 pagineWW1 in Writing - WW 1Slovenian Webclassroom Topic Resources100% (2)

- The Isonzo Front - WW 1Documento2 pagineThe Isonzo Front - WW 1Slovenian Webclassroom Topic Resources100% (2)

- Pahor Boris Letak - AngDocumento2 paginePahor Boris Letak - AngSlovenian Webclassroom Topic Resources100% (3)

- Pogledi - WW 1Documento2 paginePogledi - WW 1Slovenian Webclassroom Topic ResourcesNessuna valutazione finora

- Po Miru - WW 1Documento2 paginePo Miru - WW 1Slovenian Webclassroom Topic ResourcesNessuna valutazione finora

- The 12th Battle of Isonzo - WW 1 PDFDocumento2 pagineThe 12th Battle of Isonzo - WW 1 PDFSlovenian Webclassroom Topic Resources100% (2)

- 1914-1918-Online. International Encyclopedia of The First World War (WW1)Documento2 pagine1914-1918-Online. International Encyclopedia of The First World War (WW1)Slovenian Webclassroom Topic Resources100% (1)

- To The Eastern Front - WW 1Documento2 pagineTo The Eastern Front - WW 1Slovenian Webclassroom Topic Resources0% (1)

- 1914 1918 Online Panslavism 2017 07 12Documento4 pagine1914 1918 Online Panslavism 2017 07 12Slovenian Webclassroom Topic Resources100% (1)

- Por EngDocumento31 paginePor Engdejan4975Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (894)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Science 4 Q1 Mod2Documento18 pagineScience 4 Q1 Mod2Bern Salvador0% (1)

- E-3 Start Invitation Paying-RevisedDocumento5 pagineE-3 Start Invitation Paying-Revisedmario navalezNessuna valutazione finora

- Orthodontist Career PosterDocumento1 paginaOrthodontist Career Posterapi-347444805Nessuna valutazione finora

- Objective 8 - Minutes On Focus Group DiscussionDocumento3 pagineObjective 8 - Minutes On Focus Group DiscussionMilagros Pascua Rafanan100% (1)

- 13.2.3a Practicing Good SpeakingDocumento9 pagine13.2.3a Practicing Good SpeakingNieyfa RisyaNessuna valutazione finora

- LDM2 Practicum Portfolio For TeachersDocumento62 pagineLDM2 Practicum Portfolio For TeachersSonny Matias95% (22)

- Mohini Jain v. State of KarnatakaDocumento12 pagineMohini Jain v. State of KarnatakaNagendraKumar NeelNessuna valutazione finora

- 17EEL76 - PSS Lab ManualDocumento31 pagine17EEL76 - PSS Lab ManualnfjnzjkngjsrNessuna valutazione finora

- Youth For Environment in Schools OrganizationDocumento2 pagineYouth For Environment in Schools OrganizationCiara Faye M. PadacaNessuna valutazione finora

- LM - Dr. Jitesh OzaDocumento94 pagineLM - Dr. Jitesh OzaDakshraj RathodNessuna valutazione finora

- Curriculum Design Considerations (1) M3Documento13 pagineCurriculum Design Considerations (1) M3Hanil RaajNessuna valutazione finora

- Indiana Drivers Manual - Indiana Drivers HandbookDocumento56 pagineIndiana Drivers Manual - Indiana Drivers Handbookpermittest100% (1)

- Coarse Seminar NSTPDocumento9 pagineCoarse Seminar NSTPLorenz HernandezNessuna valutazione finora

- At Family Lesson PlanDocumento2 pagineAt Family Lesson Planapi-458486566100% (3)

- Unit 2: Language Test B: GrammarDocumento2 pagineUnit 2: Language Test B: GrammarBelen GarciaNessuna valutazione finora

- Ames - March-Monthly Instructional Supervisory PlanDocumento5 pagineAmes - March-Monthly Instructional Supervisory PlanMaricar MagallanesNessuna valutazione finora

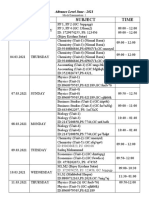

- Mock Examination Routine A 2021 NewDocumento2 pagineMock Examination Routine A 2021 Newmufrad muhtasibNessuna valutazione finora

- Table of The Revised Cognitive DomainDocumento2 pagineTable of The Revised Cognitive Domainapi-248385276Nessuna valutazione finora

- (Univocal) Gilbert Simondon, Drew S. Burk-Two Lessons On Animal and Man-Univocal Publishing (2012)Documento89 pagine(Univocal) Gilbert Simondon, Drew S. Burk-Two Lessons On Animal and Man-Univocal Publishing (2012)Romero RameroNessuna valutazione finora

- Kinhaven Music School Brochure Summer 2012Documento22 pagineKinhaven Music School Brochure Summer 2012Anthony J. MazzocchiNessuna valutazione finora

- Developing The Cambridge LearnerDocumento122 pagineDeveloping The Cambridge LearnerNonjabuloNessuna valutazione finora

- VM Foundation scholarship applicationDocumento3 pagineVM Foundation scholarship applicationRenesha AtkinsonNessuna valutazione finora

- 3330602Documento5 pagine3330602Patel ChiragNessuna valutazione finora

- Non-Test AppraisalDocumento5 pagineNon-Test AppraisalCzarmiah Altoveros89% (9)

- BE BArch First Admission List 2078 ThapathaliDocumento83 pagineBE BArch First Admission List 2078 ThapathaliAyush KarkiNessuna valutazione finora

- ASEAN Quality Assurance Framework (AQAF)Documento18 pagineASEAN Quality Assurance Framework (AQAF)Ummu SalamahNessuna valutazione finora

- Éric Alfred Leslie Satie (FrenchDocumento3 pagineÉric Alfred Leslie Satie (FrenchAidan LeBlancNessuna valutazione finora

- GUITAR MUSIC CULTURES IN PARAGUAYDocumento5 pagineGUITAR MUSIC CULTURES IN PARAGUAYHugo PinoNessuna valutazione finora

- Philippine educational system and teacher civil service exam questionsDocumento13 paginePhilippine educational system and teacher civil service exam questionsJason Capinig100% (2)

- Least Learned Competencies TemplatesDocumento5 pagineLeast Learned Competencies TemplatesMAFIL GAY BABERANessuna valutazione finora