Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Review of The Age of the Democratic Revolution by R. R. Palmer

Caricato da

Dion Baillargeon BinimelisTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Review of The Age of the Democratic Revolution by R. R. Palmer

Caricato da

Dion Baillargeon BinimelisCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Review

Author(s): C. L. Mowat

Review by: C. L. Mowat

Source: The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 17, No. 2 (Apr., 1960), pp. 257-259

Published by: Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1943360

Accessed: 18-06-2015 09:08 UTC

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/

info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content

in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship.

For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to The William and Mary Quarterly.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 150.244.109.133 on Thu, 18 Jun 2015 09:08:09 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

257

REVIEWSOF BOOKS

fromdaring,secrecy,superbwoodsmanship,and thoroughpreparationand

training.His superior,GeneralGage, envied his militaryreputation,and

Sir William Johnsonfeared his effortsto acquireland and his influence

with the Indians.Betweenthem they laid him low, but it took considerable doing. If Rogers were constantlyin debt, he borrowedfirst to pay

his rangers-and was never fully repaid. Accusationsof treason made

againsthim were manifestfabricationsto discredithim. And, though he

fought for Englandduringthe Revolution,it was only afterCongresshad

rejectedhis services.

On the whole admirablywritten,this volume has its flaws.Johnson's

hatredand that of Gage are explained,but not the oppositionof so many

more of Rogers'associates.Amherst'sambivalentattitudetoward him is

not elucidated.(comparep. I45 and p. I58) There are a numberof proofreadingslips in spelling and dates (Rogers'first rangercommissionwas

dated i756, not I760), and the indexing is incomplete.Yet the volume is

swift-paced,the phrasingoften vivid, and the researchextensive.Rogers

was clearlythe victim of a conspiracywhich historiansever since have

compoundedby neglecting him; perhaps now the injustice may be

partiallyredressed.

CortlandState Collegeof Education

Cortland,New York

DONALD

H.

STEWART

The Age of the Democratic Revolution: A Political History of Europe

The Challenge. By R. R. PALMER. (Princeton:

and America, I760-i800:

Princeton University Press, 1959. Pp. 534. $7.50.)

In this arresting book Professor Palmer (to borrow from his title)

challenges historians by his example to undertake large works singlehanded, scorning the collaborative method, and to turn from parochial or

even national researches to the broad, synoptic view of history. He sees

in the period from I760 to i79i a unity embodied in the Democratic

Revolution, the challenge of democratic ideas to government by privilege,

whether in Europe or the British colonies in North America. In a sequel

he will describe the "struggle" of these forces between i7gi and i8oo.

This democratic movement is traced in Britain and her American

colonies, in France, Sweden, Geneva, and the Hapsburg Empire during

the i760's. After the American Revolution and in spite of its influence,

Professor Palmer descries and describes an "aristocraticresurgence" in the

same European countries, affecting even Ireland and halted only-and

This content downloaded from 150.244.109.133 on Thu, 18 Jun 2015 09:08:09 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

258

WILLIAM AND MARY QUARTERLY

there temporarily-in Poland. In France this revolte nobilaire was the

proximate cause of the Revolution.

From an enterprise of this scale and boldness complete success is hardly

to be expected. Professor Palmer's style is clear if undistinguished, with an

unnecessary (because unpolemical) intrusion of the personal pronoun. He

is occasionally repetitious and is led into needlessly discursive accounts of

Rousseau and Voltaire, Delolme, Mably, Mounier, Burke, and other men

whose ideas interest him. He is too self-conscious in his unusual task

("occupied more with European than American history, I have been able

only to sample this literature" of the American Revolution: p. i86). He

has, in fact, confused analysis with description. His task is not to narrate

the various revolutions of the time but to correlate them. Had he confined

himself to this, he would have produced a much shorter, easier, and more

closely reasoned work. Instead of a brilliant essay we are given a somewhat unwieldy book.

Not that it does not have great merits. There is a freshness of view

which comes from a novel perspective. Parallels not always observed

become clear: between American committees of correspondence and the

similar committees of the English county associations of I780, between

representativeson mission in New Jersey during the Revolutionary War

and in France a few years later. Interesting questions are asked and answered: the comparative tax burdens in the American colonies and several

European countries, the comparative numbers of American loyalists and

French emigres. We are reminded of Burke's essential conservatism long

before the French Revolution and springing chiefly from his "adulation

of Parliament." (p. 309) We are shown the irresponsibility of the Whigs

in opposition before and during the American war: they undermined

American respect for the King and for Parliament and fanned American

discontent which they had no power or ideas for relieving. (pp. I72-I73)

Not all Professor Palmer's parallels will command assent. It can be

argued that both in Great Britain and in Ireland aristocratic (or oligarchic) government was never seriously challenged in the I76o's and so

could experience no "resurgence" in the eighties. Rather, George III's

intervention in politics challenged the power of a Whig clique and sent

some of its members into opposition. When the American war went

badly this clique temporarily reasserted itself, using the old suspicions of

country against court which produced the county associations. It soon

parted from the radicals, the true reformers; and Pitt was able to restore

the former mixture of oligarchic government and limited royal influence.

It is thus an exaggeration to ascribe "the climax and failure of the early

movement for parliamentary reform in England" (p. i85) to the Ameri-

This content downloaded from 150.244.109.133 on Thu, 18 Jun 2015 09:08:09 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REVIEWS OF BOOKS

259

can Revolution. The remark that "with Pitt in office the aristocracy was

kept at a distance" (p. 302) reads strangely. Nor can Grattan's Parliament

be represented as the triumph of democracy in Ireland. The government,

hard pressed in the war, made a concession to the nationalism of the

Anglo-Irish gentry, but then allowed the continuing strength of the

Protestant "ascendancy" and the influence of Fitzgibbon and Beresford

at Dublin Castle to nullify its effect-hardly a case of aristocratic resurgence.

This is not to deny a,- kinship between democratic movements in

Europe and America. Professor Palmer does not claim that the American

Revolution grew out of the European movements, but he does, in a

striking chapter, show how pervasive was its inspiration upon Europe.

It furnished a model for putting into effect the ideas of government by

consent and the sovereignty of the people. (p. 214) It familiarized the

"convention"as a body to frame and ratify a constitution. In John Adams's

preamble to the Massachusetts constitution of I780, it anglicized the word

"citizen." Above all, in the making of the state and federal constitutions

(as an admirable chapter, "The People as Constituent Power," shows) it

demonstrated that a sovereign people could form a government and put

themselves under it. Thus the American Revolution "inspired the sense

of a new era . . . it dethroned England, and set up America, as a model

for those seeking a better world." (p. 282)

Yet-one last caveat-the American Revolution represents the democratic challenge only in a limited sense. When it came to war with Great

Britain, it was "a struggle between democratic and aristocratic forces."

(p. 202) But the government of the American colonies had never been

aristocratic: the colonial oligarchies (from which most of the Revolutionary leaders came) were based, as Professor Palmer shows, on institutions far more democratic (for example in the franchise) than in contemporary Britain. Democracy, like other American attributes, had

evolved in response to the American environment, whose influence

Professor Boorstin has so convincingly described. "In America they claim

... to be perfect States, not otherwise dependent on Great Britain than

by having the same King," wrote Governor Bernard in 1765. (p. i62) The

Americans rebelled, not against an old order as in Europe, but against the

British attempt to impose a new order in the imperial reorganization

after I763. Without this challenge, would American democracy have

formulated and demonstrated its ideas in time to furnish inspiration to the

democratic revolution in Europe?

University College of North Wf'ales,

C. L. MOWAT

Bangor

This content downloaded from 150.244.109.133 on Thu, 18 Jun 2015 09:08:09 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Imperial Nation: Citizens and Subjects in the British, French, Spanish, and American EmpiresDa EverandThe Imperial Nation: Citizens and Subjects in the British, French, Spanish, and American EmpiresNessuna valutazione finora

- American Revolution Essay ThesisDocumento4 pagineAmerican Revolution Essay ThesisPayToDoMyPaperPortland100% (1)

- The American Revolution - Revisions in Need of RevisingDocumento14 pagineThe American Revolution - Revisions in Need of RevisingBrandon ShihNessuna valutazione finora

- The Elusive Republic: Political Economy in Jeffersonian AmericaDa EverandThe Elusive Republic: Political Economy in Jeffersonian AmericaNessuna valutazione finora

- Organization of American Historians, Oxford University Press The Journal of American HistoryDocumento40 pagineOrganization of American Historians, Oxford University Press The Journal of American HistoryYusry SulaimanNessuna valutazione finora

- Decline and Fall: The End of Empire and the Future of Democracy in 21st Century AmericaDa EverandDecline and Fall: The End of Empire and the Future of Democracy in 21st Century AmericaNessuna valutazione finora

- Thesis For American Revolution EssayDocumento5 pagineThesis For American Revolution Essaypak0t0dynyj3100% (2)

- Victorian People: A Reassessment of Persons and Themes, 1851-67Da EverandVictorian People: A Reassessment of Persons and Themes, 1851-67Nessuna valutazione finora

- Historiography of Revolutionary AmericaDocumento5 pagineHistoriography of Revolutionary AmericaLu TzeNessuna valutazione finora

- The Constitution of the United States: A Brief Study of the Genesis, Formulation and Political Philosophy of the ConstitutionDa EverandThe Constitution of the United States: A Brief Study of the Genesis, Formulation and Political Philosophy of the ConstitutionNessuna valutazione finora

- Causes of The American Revolution Thesis StatementDocumento8 pagineCauses of The American Revolution Thesis Statementmcpvhiief100% (2)

- An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United StatesDa EverandAn Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United StatesNessuna valutazione finora

- Thesis American RevolutionDocumento5 pagineThesis American Revolutionlaurataylorsaintpaul100% (1)

- The Abolition Crusade and Its Consequences: Four Periods of American HistoryDa EverandThe Abolition Crusade and Its Consequences: Four Periods of American HistoryNessuna valutazione finora

- Causes of American Revolution ThesisDocumento8 pagineCauses of American Revolution Thesisfjh1q92b100% (2)

- American Revolution Thesis StatementDocumento6 pagineAmerican Revolution Thesis StatementPayToWriteMyPaperArlington100% (2)

- The American Yawp: A Massively Collaborative Open U.S. History Textbook, Vol. 2: Since 1877Da EverandThe American Yawp: A Massively Collaborative Open U.S. History Textbook, Vol. 2: Since 1877Joseph L. LockeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (2)

- American Revolution Thesis IdeasDocumento8 pagineAmerican Revolution Thesis Ideassarahmitchelllittlerock100% (1)

- Winning America's Second Civil War: Progressivism's Authoritarian Threat, Where It Came from, and How to Defeat ItDa EverandWinning America's Second Civil War: Progressivism's Authoritarian Threat, Where It Came from, and How to Defeat ItNessuna valutazione finora

- Review of Revolutionary Mentality Development Symposium PapersDocumento4 pagineReview of Revolutionary Mentality Development Symposium PapersRaphael FalcãoNessuna valutazione finora

- Our Heritage of Liberty - its Origin, its Achievement, its CrisisDa EverandOur Heritage of Liberty - its Origin, its Achievement, its CrisisNessuna valutazione finora

- Gavin Murray-Miller - Revolutionary Europe - Politics, Community and Culture in Transnational Context, 1775-1922 (2020) - 13-34Documento30 pagineGavin Murray-Miller - Revolutionary Europe - Politics, Community and Culture in Transnational Context, 1775-1922 (2020) - 13-34Amalia LopezNessuna valutazione finora

- The Great Events by Famous Historians, Volume 14Da EverandThe Great Events by Famous Historians, Volume 14Nessuna valutazione finora

- Good Thesis For American Revolution EssayDocumento6 pagineGood Thesis For American Revolution Essaygjh9pq2a100% (1)

- Gordon Wood The American Revolution ThesisDocumento6 pagineGordon Wood The American Revolution Thesisgj9zvt51100% (2)

- The Hidden History of American Democracy: Rediscovering Humanity's Ancient Way of LivingDa EverandThe Hidden History of American Democracy: Rediscovering Humanity's Ancient Way of LivingNessuna valutazione finora

- Research Paper American RevolutionDocumento7 pagineResearch Paper American Revolutionefj02jba100% (1)

- The Future of American PowerDocumento27 pagineThe Future of American PowerMichiru2011Nessuna valutazione finora

- Empire and Nation: The American Revolution in the Atlantic WorldDa EverandEmpire and Nation: The American Revolution in the Atlantic WorldNessuna valutazione finora

- Thesis Statement On Causes of American RevolutionDocumento6 pagineThesis Statement On Causes of American RevolutionScientificPaperWritingServicesKansasCity100% (2)

- Practicing Democracy: Popular Politics in the United States from the Constitution to the Civil WarDa EverandPracticing Democracy: Popular Politics in the United States from the Constitution to the Civil WarNessuna valutazione finora

- Battle For A More Perfect UnionDocumento18 pagineBattle For A More Perfect UnionAndrewNessuna valutazione finora

- Expansion of EuropeDocumento231 pagineExpansion of Europegreatbluemarlin2Nessuna valutazione finora

- Causes of The American Revolution Unit OverviewDocumento6 pagineCauses of The American Revolution Unit Overviewapi-341830053Nessuna valutazione finora

- Imperialism Essay Thesis StatementDocumento4 pagineImperialism Essay Thesis Statementafbtibher100% (2)

- FinalproductDocumento5 pagineFinalproductapi-327730930Nessuna valutazione finora

- American Imperialism-Andrew BakerDocumento12 pagineAmerican Imperialism-Andrew BakerVlad SurdeaNessuna valutazione finora

- American Revolution Research Paper TopicsDocumento7 pagineAmerican Revolution Research Paper Topicsgosuzinifet2100% (1)

- Early Journal Content On JSTOR, Free To Anyone in The WorldDocumento3 pagineEarly Journal Content On JSTOR, Free To Anyone in The WorldjgmailNessuna valutazione finora

- 1776 Was More About Representation Than TaxationDocumento3 pagine1776 Was More About Representation Than TaxationOscar AlfaroNessuna valutazione finora

- Ramsay His T RevolutionDocumento496 pagineRamsay His T RevolutionAimal KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- New York State Historical Association Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To New York HistoryDocumento5 pagineNew York State Historical Association Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To New York Historypavlosmakridakis2525Nessuna valutazione finora

- Glorious Revolution Student MaterialsDocumento11 pagineGlorious Revolution Student MaterialsLuiz Paulo MagalhaesNessuna valutazione finora

- Final Annotated BibliographyDocumento4 pagineFinal Annotated Bibliographyapi-389064150Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Age of Revolution Mod 3-ContentDocumento11 pagineThe Age of Revolution Mod 3-ContentKavita BadhaniNessuna valutazione finora

- American Revolution in World HistoryDocumento11 pagineAmerican Revolution in World HistorySecret SecretNessuna valutazione finora

- American Revolution Thesis TopicsDocumento4 pagineAmerican Revolution Thesis Topicssarahuntercleveland100% (2)

- The History of the United States: A Sweeping Presentation by Three Award-Winning ProfessorsDocumento3 pagineThe History of the United States: A Sweeping Presentation by Three Award-Winning ProfessorsLuiz Henrique LNessuna valutazione finora

- According To His Frontier Thesis Frederick Jackson Turner Proposed All of The FollowingDocumento4 pagineAccording To His Frontier Thesis Frederick Jackson Turner Proposed All of The FollowingsprxzfuggNessuna valutazione finora

- Continued After The Independence by The Domestic Political Elites. It Was A Revolution To ConserveDocumento11 pagineContinued After The Independence by The Domestic Political Elites. It Was A Revolution To ConserveIvan JankovicNessuna valutazione finora

- Where Is Britain GoingDocumento7 pagineWhere Is Britain Goingheather heatherNessuna valutazione finora

- The MIT Press American Academy of Arts & SciencesDocumento21 pagineThe MIT Press American Academy of Arts & SciencesyalcinaybikeNessuna valutazione finora

- Interesting Topics For Research Papers American HistoryDocumento5 pagineInteresting Topics For Research Papers American HistoryxhzscbbkfNessuna valutazione finora

- Thesis Statement For French RevolutionDocumento4 pagineThesis Statement For French Revolutionelizabethjenkinsatlanta100% (2)

- Frederick Jackson Frontier Thesis SummaryDocumento6 pagineFrederick Jackson Frontier Thesis Summarygowlijxff100% (2)

- AutoText Technologies, Inc. v. Apple, Inc. Et Al - Document No. 3Documento2 pagineAutoText Technologies, Inc. v. Apple, Inc. Et Al - Document No. 3Justia.comNessuna valutazione finora

- Order Against DLF LimitedDocumento220 pagineOrder Against DLF LimitedShyam SunderNessuna valutazione finora

- The Nay Pyi Taw Development Law PDFDocumento7 pagineThe Nay Pyi Taw Development Law PDFaung myoNessuna valutazione finora

- Government of Canada: Structure and FunctionDocumento7 pagineGovernment of Canada: Structure and FunctionAthena HuynhNessuna valutazione finora

- Constantino v. CuisiaDocumento2 pagineConstantino v. CuisiaRonald Jay GopezNessuna valutazione finora

- Sponsor Change: Three Upline Approval FormDocumento1 paginaSponsor Change: Three Upline Approval FormClaudiamar CristisorNessuna valutazione finora

- Sec 3 CompilationDocumento6 pagineSec 3 CompilationMatthew WittNessuna valutazione finora

- Burma Will Remain Rich, Poor and Controversial': Published: 9 April 2010Documento11 pagineBurma Will Remain Rich, Poor and Controversial': Published: 9 April 2010rheito6745Nessuna valutazione finora

- Waqf Registration Form 1Documento2 pagineWaqf Registration Form 1SalamNessuna valutazione finora

- Goals of Civil Justice and Civil Procedure in Contemporary Judicial SystemsDocumento262 pagineGoals of Civil Justice and Civil Procedure in Contemporary Judicial Systems* BC *Nessuna valutazione finora

- Act 658 Electronic Commerce Act 2006 MalaysiaDocumento17 pagineAct 658 Electronic Commerce Act 2006 MalaysiaJunXuanLohNessuna valutazione finora

- Trade Unions ActDocumento35 pagineTrade Unions ActAnam AminNessuna valutazione finora

- Imbong v. Ochoa 4. The Question of Constitutionality Must Be Raised at The Earliest OpportunityDocumento3 pagineImbong v. Ochoa 4. The Question of Constitutionality Must Be Raised at The Earliest OpportunitychristineNessuna valutazione finora

- Impact of Company, Contract, Competition & Data Protection Law on Business (40/40Documento3 pagineImpact of Company, Contract, Competition & Data Protection Law on Business (40/40GasluNessuna valutazione finora

- Is Silence Truly AcquiessenceDocumento9 pagineIs Silence Truly Acquiessencebmhall65100% (1)

- 29 - Abeto V GarciaDocumento4 pagine29 - Abeto V GarcialunaNessuna valutazione finora

- An Essay On The Foreign Policy of IndiaDocumento2 pagineAn Essay On The Foreign Policy of IndiatintucrajuNessuna valutazione finora

- Identify Harassing Calls with Call TraceDocumento3 pagineIdentify Harassing Calls with Call TracesayanNessuna valutazione finora

- Petitioners Respondent Atty. Noe Q. Laguindam Atty. Elpidio I. DigaumDocumento11 paginePetitioners Respondent Atty. Noe Q. Laguindam Atty. Elpidio I. DigaumRomy IanNessuna valutazione finora

- How Do You Compute The Assessed Value?: Assessed Value Fair Market Value X Assessment LevelDocumento7 pagineHow Do You Compute The Assessed Value?: Assessed Value Fair Market Value X Assessment Leveljulie anne mae mendozaNessuna valutazione finora

- Contract Management Issues Commonly Arising During Implementation and Doubts RaisedDocumento2 pagineContract Management Issues Commonly Arising During Implementation and Doubts RaisedSandeep JoshiNessuna valutazione finora

- Labour Law DismissalDocumento35 pagineLabour Law DismissalnokwandaNessuna valutazione finora

- GSIS v. Albert Velasco, G.R. No. 196564, Aug. 7, 2017Documento4 pagineGSIS v. Albert Velasco, G.R. No. 196564, Aug. 7, 2017sophiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Updated Bandolera Constitution Appendix A-General InfoDocumento3 pagineUpdated Bandolera Constitution Appendix A-General Infoapi-327108361Nessuna valutazione finora

- Soriano vs. PeopleDocumento3 pagineSoriano vs. Peoplek santosNessuna valutazione finora

- Rules of EngagementDocumento3 pagineRules of EngagementAlexandru Stroe100% (1)

- Contract Formation Issues in Betty and Albert's Car Sale NegotiationsDocumento2 pagineContract Formation Issues in Betty and Albert's Car Sale NegotiationsRajesh NagarajanNessuna valutazione finora

- Consti Citizenship Class NotesDocumento4 pagineConsti Citizenship Class NotesIssah SamsonNessuna valutazione finora

- 23 Motion To Compel Determination 246 Decatur Street Eleanor PhillipsDocumento7 pagine23 Motion To Compel Determination 246 Decatur Street Eleanor PhillipsTaylorbey American NationalNessuna valutazione finora

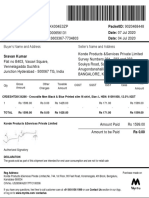

- Gstin Number: Packetid: 9020468448 Invoice Number: Date: 07 Jul 2020 Order Number: Date: 04 Jul 2020Documento1 paginaGstin Number: Packetid: 9020468448 Invoice Number: Date: 07 Jul 2020 Order Number: Date: 04 Jul 2020Sravan KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- The Russia Hoax: The Illicit Scheme to Clear Hillary Clinton and Frame Donald TrumpDa EverandThe Russia Hoax: The Illicit Scheme to Clear Hillary Clinton and Frame Donald TrumpValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (11)

- Camelot's Court: Inside the Kennedy White HouseDa EverandCamelot's Court: Inside the Kennedy White HouseValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (17)

- Nine Black Robes: Inside the Supreme Court's Drive to the Right and Its Historic ConsequencesDa EverandNine Black Robes: Inside the Supreme Court's Drive to the Right and Its Historic ConsequencesNessuna valutazione finora

- The Smear: How Shady Political Operatives and Fake News Control What You See, What You Think, and How You VoteDa EverandThe Smear: How Shady Political Operatives and Fake News Control What You See, What You Think, and How You VoteValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (16)

- The Deep State: How an Army of Bureaucrats Protected Barack Obama and Is Working to Destroy the Trump AgendaDa EverandThe Deep State: How an Army of Bureaucrats Protected Barack Obama and Is Working to Destroy the Trump AgendaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (4)

- Commander In Chief: FDR's Battle with Churchill, 1943Da EverandCommander In Chief: FDR's Battle with Churchill, 1943Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (16)

- We've Got Issues: How You Can Stand Strong for America's Soul and SanityDa EverandWe've Got Issues: How You Can Stand Strong for America's Soul and SanityNessuna valutazione finora

- Thomas Jefferson: Author of AmericaDa EverandThomas Jefferson: Author of AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (107)

- Game Change: Obama and the Clintons, McCain and Palin, and the Race of a LifetimeDa EverandGame Change: Obama and the Clintons, McCain and Palin, and the Race of a LifetimeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (572)

- The Courage to Be Free: Florida's Blueprint for America's RevivalDa EverandThe Courage to Be Free: Florida's Blueprint for America's RevivalNessuna valutazione finora

- Power Grab: The Liberal Scheme to Undermine Trump, the GOP, and Our RepublicDa EverandPower Grab: The Liberal Scheme to Undermine Trump, the GOP, and Our RepublicNessuna valutazione finora

- Reading the Constitution: Why I Chose Pragmatism, not TextualismDa EverandReading the Constitution: Why I Chose Pragmatism, not TextualismNessuna valutazione finora

- Witch Hunt: The Story of the Greatest Mass Delusion in American Political HistoryDa EverandWitch Hunt: The Story of the Greatest Mass Delusion in American Political HistoryValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (6)

- Stonewalled: My Fight for Truth Against the Forces of Obstruction, Intimidation, and Harassment in Obama's WashingtonDa EverandStonewalled: My Fight for Truth Against the Forces of Obstruction, Intimidation, and Harassment in Obama's WashingtonValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (21)

- Blood Money: Why the Powerful Turn a Blind Eye While China Kills AmericansDa EverandBlood Money: Why the Powerful Turn a Blind Eye While China Kills AmericansValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (10)

- Trumpocracy: The Corruption of the American RepublicDa EverandTrumpocracy: The Corruption of the American RepublicValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (68)

- The Quiet Man: The Indispensable Presidency of George H.W. BushDa EverandThe Quiet Man: The Indispensable Presidency of George H.W. BushValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1)

- The Last Republicans: Inside the Extraordinary Relationship Between George H.W. Bush and George W. BushDa EverandThe Last Republicans: Inside the Extraordinary Relationship Between George H.W. Bush and George W. BushValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (6)

- Resistance: How Women Saved Democracy from Donald TrumpDa EverandResistance: How Women Saved Democracy from Donald TrumpNessuna valutazione finora

- The Great Gasbag: An A–Z Study Guide to Surviving Trump WorldDa EverandThe Great Gasbag: An A–Z Study Guide to Surviving Trump WorldValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (9)

- An Ordinary Man: The Surprising Life and Historic Presidency of Gerald R. FordDa EverandAn Ordinary Man: The Surprising Life and Historic Presidency of Gerald R. FordValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5)

- Profiles in Ignorance: How America's Politicians Got Dumb and DumberDa EverandProfiles in Ignorance: How America's Politicians Got Dumb and DumberValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (80)

- The Magnificent Medills: The McCormick-Patterson Dynasty: America's Royal Family of Journalism During a Century of Turbulent SplendorDa EverandThe Magnificent Medills: The McCormick-Patterson Dynasty: America's Royal Family of Journalism During a Century of Turbulent SplendorNessuna valutazione finora