Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Listening Styles and Listening Strategies

Caricato da

BladyPanopticoCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Listening Styles and Listening Strategies

Caricato da

BladyPanopticoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Listening Styles and Listening Strategies

06/12/2014 14:56

Listening Styles and Listening Strategies

David Huron

Society for Music Theory 2002 Conference.

Columbus, Ohio

November 1, 2002

Handout

Listening mode: a distinctive attitude or approach that can be brought to bear on a listening experience.

Some simple possible listening modes:

1. Distracted listening. Distracted listening occurs where the listener pays no conscious attention

whatsoever to the music. Typically, the listener is occupied with other tasks, and may even be

unaware of the existence of the music.

2. Tangential listening. Tangential listening is similar to distracted listening except that the listener is

engaged in thought whose origin can be traced to the music, but the thought is largely tangential to

the perceptual experience itself. An auditor is engaged in tangential listening when preoccupied

with thoughts such as: why did the concert organizers program me this work? Isn't that the oboist

who played at the last chamber music concert? I wonder how much money the guest artist makes in

a year? Tangential listening behaviors may occasionally approach what might be called

metaphysical listening:

3. Metaphysical listening. Metaphysical listening is also similar to distracted listening insofar as the

listener may not be especially attentive to the on-going perceptual experience. But the listener may

be engaged in thinking about questions of some importance related to the work, such as: what

motivated the composer to write this work? what does this music mean? why do I find this work so

appealing? etc.

4. Signal listening. Truax coined the term "listening-in-readiness" to denote the state of a listener

waiting for some expected auditory event. E.g., rather than laboriously count hundreds of bars of

rest, a percussionist may recognize a certain musical passage as a cue or "alarm" -- signaling the

need to prepare to perform. In effect, the music is heard in terms of a set of signals or sign-posts.

Similarly, a dance couple may wait for a dance tune with a desired tempo before proceeding on to

the dance floor. A more sophisticated example of signal listening occurs whe listening to a work

known or assumed to be in sonata-allegro form; the listener will wait for features in the music that

signal the advent of the next structural division, such as the advent of the development section, or

the beginning of the second theme in the recapitulation.

5. Sing-along listening. This form of listening is characterized by the listener mentally "singingalong" with the music. This mode of listening presupposes that the listener is already familiar with

the work. Distinctive of this listening mode is a highly linear conception of the work in which a

replay of memory is synchronized with an actual rendition. The listener's behavior is not unlike that

http://www.musicog.ohio-state.edu/Huron/Talks/SMT.2002/handout.html

Page 1 of 4

Listening Styles and Listening Strategies

06/12/2014 14:56

of a recording which, when started at any given point in the music, can continue forward to the end

of the work. Where a work is particularly well known to a listener, sing-along listening may occur

as a purely mental activity without the mnemonic assistance of an actual performance. (See the

work of Andrea Halpern.)

6. Lyric listening. In music containing a vocal text, a listener may pay special attention to "catching"

the lyrics and attending to their meaning. Lyric listening is possible only when the music contains

lyrics in a language which is understood by the listener. Where the lyrics of a work are well known

to a listener, the lyrics themselves may act as mnemonics for a form of "sing-along listening."

7. Programmatic listening. While listening to music, many listeners imagine certain situations or

visualize certain scenes -- such as rolling waves, mountain vistas, city streets, and so forth. In

programmatic listening the listening experience is dominated by such forms of non-musical

referentiality. Musical works that are overtly programmatic in construction may be assumed to

enhance or promote such a listening mode. However, programmatic listening may arise even in the

case of ostensibly non-programmatic works.

8. Allusive listening. Allusive listening may be said to occur where a listener relates moments or

features of the music to similar moments or features in other musical works. (`This reminds me of a

passage in Bartk ...'). Allusive listening may be viewed as a form of referential listening in which

the referential connection is made to the domain of music itself. Philip Tagg (1979) has made

extensive use of allusive listening as a tool for studying musical meaning. Tagg has created musical

"dictionaries" by asking listeners to construct lists of musical works of which a given work reminds

them.

9. Reminiscent listening. In reminiscent listening, music serves to remind the auditor of past

experiences or circumstances in which the music was previously heard or encountered. The

reminiscent listener's primary focus of attention is on the remembrance of past events -- or more

particularly, on the remembrance of emotions experienced in conjunction with the past events.

10. Identity listening. A listener engaged in asking any "what is" question regarding the music is

engaged in what might be called "identity listening." Typical "what is" questions are: What is this

instrument I am listening to? Is that a Neapolitan sixth chord? What is the meter signature? What

language are the lyrics in? Who might the composer be? What is the style of this music called? etc.

Identity listening often employs allusive listening as a problem-solving tactic.

11. Retentive listening. The goal of "retentive listening" is to remember what is being heard. Retentive

listening is most commonly encountered when music students perform ear training or dictation

exercises. Unlike many other modes of listening, retentive listening is very much a problem-solving

behavior. A composer in the process of improvising might use retentive listening skills to recall a

fleeting passage or an appealing juxtaposition of notes.

12. Fault listening. Fault listening occurs where the listener is mentally keeping a leger of faults or

problems. A high-fidelity buff may note problems in sound reproduction. A conservatory teacher

may note mistakes in execution, problems of intonation, ensemble balance, phrasing, etc. A

composer is apt to identify what might be considered lapses of skill or instances of poor musical

judgment. Fault listening tends to be adopted as a strategy under three circumstances: 1) where an

obvious fault has occurred, the listener switches from a previous listening mode and becomes

vigilant for the occurrence of more faults (this is a type of signal listening); 2) where the role of the

listener is necessarily critical -- as in tutors, conductors, or music critics; or 3) where the listener has

some a priori reason to mistrust the skill or integrity of the composer, performer, conductor, audio

http://www.musicog.ohio-state.edu/Huron/Talks/SMT.2002/handout.html

Page 2 of 4

Listening Styles and Listening Strategies

06/12/2014 14:56

system, etc.

13. Feature listening. This type of listening is characterized by the listener's disposition to identify

major "features" that occur in the work -- such as motifs, distinctive rhythms, instrumentation, etc.

The listener identifies the recurrence of such features, and also identifies the evolutions or changes

which the features undergo. The "feature listening" mode may be considered superficially to be a

creative union of two other listening modes: retentive listening (identification and remembrance of

features), and signal listening (recognition of previously occurring features).

14. Innovation listening. A variant form of allusive listening is one based, not upon the recognition of

similarities to previous compositions, but upon the identification of significant musical novelty.

Innovation listening is characterized by a vigilant listening-in-readiness for a musical feature,

gesture, or technique that is unprecedented in the listener's experience. Composers may be

especially prone to engage in innovation listening.

15. Memory scan listening. When an auditor knows a work by memory, a special type of signal

listening called scan listening is possible. An auditor may approach a memorized work with a

question concerning the occurrence of a certain event: For example, the auditor may be interested in

knowing whether the composer has used timpani in a given work; or does the word "but" occur in

the lyrics to "Row Row Row Your Boat?" The scan listener will mentally execute a speedy

rendition of a work in order to answer a given question. What distinguishes scan listening from

signal listening is that the auditor tends to be impatient: the tempo of the music can be doubled or

quadrupled to advantage for the scan listener.

16. Directed listening. Directed listening entails a form of selective attention to one element of a

complex texture; the listener purposely excludes or ignores other aspects of the music. For example,

the auditor may attend to a single instrument for a short or prolonged period of time. Directed

listening may ensue as a result of a listener's special interest, or may result from suggestions made

by others. When a listener is concurrently viewing a notated score, it is possible that a visual

attraction or interest in a particular aspect of a score may cause the listener to selectively attend to

the corresponding sounds. The Norton Scores use a highlighting method to draw attention to various

parts in orchestral scores. These scores thus dispose listeners to adopt a directed listening mode.

17. Distance listening. Distance listening is characterized by an ongoing iterative recapitulation of the

music up to the current moment in the work. As the music unfolds, the listener attempts to thread

together past events and to build a complete scenario or over-view of the entire work. The distance

listener is apt to make mental notes of the advent of new "sections" in the work. Distance listening

may be likened to the task of memorizing a list of words. Beginning with a few words, the

memorized words are iteratively repeated, each time adding a new word to the memorized list.

18. Ecstatic listening. The term `ecstatic listening' is meant here in a very concrete and technical way.

On occasion music will elicit a sensation of "shivers" localized in the back, neck and shoulders of

an aroused listener -- a physiological response technically called frisson. The frisson experience

normally has a duration of no more than four or five seconds. It begins as a flexing of the skin in the

lower back, rising upward, inward from the shoulders, up the neck, and sometimes across to the

cheeks and onto the scalp. The face may become flush, hair follicles flex the hairs into standing

position, and goose bumps may appear (piloerection). Frequently, a series of `waves' will rise up the

back in rapid succession. The listener feels the music to have elicited an ecstatic moment and tends

to regard the experience as involuntary. Goldstein (1980) has shown that some listeners report

reduced excitement when under a clinically-administered dose of an opiate receptor antagonist,

naloxone -- suggesting that music engenders endogenous opioid peptides characteristic of

http://www.musicog.ohio-state.edu/Huron/Talks/SMT.2002/handout.html

Page 3 of 4

Listening Styles and Listening Strategies

06/12/2014 14:56

pleasurable experiences. Sloboda (1991) has found evidence linking "shivers" responses to works

especially loved by subjects.

19. Emotional listening. Emotional listening is characterized by deeply felt emotion. The music

engenders feels of sorrow or joy, resignation, great satisfaction. Occasionally there will be overt

signs of emotion, such as the sensation of a lump in one's throat, imminent or overt weeping, or

smiling. The emotions may be related to current events in the listener's life, but the feelings are

more apt to seem non-specific and to arise `from nowhere'.

20. Kinesthetic listening. This form of listening is characterized by the auditor's compulsion to move.

Feet may tap, hands may conduct, or the listener may feel the urge to dance. The experience is not

so much one of `listening' to the music, as the music `permeating' the body. Kinesthetic listening is

best described as `motivation' rather than `contemplation'.

21. Performance listening. When performers listen to works that are part of their own repertoire, they

may experience a form of vicarious performance. For conductors, instrumentalists, and vocalists,

arms, fingers, and vocal cords may subliminally re-create the gestures and performance actions

involved during actual performance. In such cases, listening may be mediated by an acute

awareness of the listener's body. For example, musical passages that are difficult to execute may

evoke a heightened sense of tension -- whether or not the sonic gesture conveys some musical

tension.

N.B. This list is not intended to be exhaustive.

Return to Presentation

Return to Table of Contents

http://www.musicog.ohio-state.edu/Huron/Talks/SMT.2002/handout.html

Page 4 of 4

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Representing Sound: Notes on the Ontology of Recorded Musical CommunicationsDa EverandRepresenting Sound: Notes on the Ontology of Recorded Musical CommunicationsNessuna valutazione finora

- Sonic Bodies: Text, Music, and Silence in Late Medieval EnglandDa EverandSonic Bodies: Text, Music, and Silence in Late Medieval EnglandNessuna valutazione finora

- Foundations of Musical GrammarDocumento4 pagineFoundations of Musical GrammarMarche DelgadoNessuna valutazione finora

- MMCS303 Music, Sound and Moving ImageDocumento13 pagineMMCS303 Music, Sound and Moving ImageBen BiedrawaNessuna valutazione finora

- Creative Thinking in Music The Assessment Webster 1989Documento37 pagineCreative Thinking in Music The Assessment Webster 1989Persefoni ClemNessuna valutazione finora

- Margie Borschke - This Is Not A Remix - Piracy, Authenticity and Popular Music - Copy, A BriefhistoryDocumento21 pagineMargie Borschke - This Is Not A Remix - Piracy, Authenticity and Popular Music - Copy, A BriefhistoryQvetzann TinocoNessuna valutazione finora

- Concerning SprechgesangDocumento5 pagineConcerning SprechgesangZacharias Tarpagkos100% (1)

- Educating Music Teachers For The 21st Century PDFDocumento229 pagineEducating Music Teachers For The 21st Century PDFAline RochaNessuna valutazione finora

- Music, Movies and Meaning: Communication in Film-Makers’ Search For Pre-Existing Music, and The Implications For Music Information RetrievalDocumento6 pagineMusic, Movies and Meaning: Communication in Film-Makers’ Search For Pre-Existing Music, and The Implications For Music Information Retrievalmachinelearner100% (2)

- Music Library Association Notes: This Content Downloaded From 163.10.0.68 On Wed, 10 Oct 2018 19:39:46 UTCDocumento8 pagineMusic Library Association Notes: This Content Downloaded From 163.10.0.68 On Wed, 10 Oct 2018 19:39:46 UTCCereza EspacialNessuna valutazione finora

- Cultural Sociology of Popular MusicDocumento23 pagineCultural Sociology of Popular Musicalexandru_bratianu1301Nessuna valutazione finora

- Rudolph RetiDocumento3 pagineRudolph RetiAnonymous J5vpGuNessuna valutazione finora

- Creative and Digital Technologies: Entry 2012Documento32 pagineCreative and Digital Technologies: Entry 2012Alba Valeria PortilloNessuna valutazione finora

- The Case For Technology in Music EducationDocumento12 pagineThe Case For Technology in Music EducationAndrew T. Garcia93% (15)

- Pop Music, Culture and IdentityDocumento16 paginePop Music, Culture and IdentitySabrininha Porto100% (1)

- Middleton - Popular Music Analysis and Musicology - Bridging The GapDocumento15 pagineMiddleton - Popular Music Analysis and Musicology - Bridging The GapTomas MarianiNessuna valutazione finora

- Kompositionen für hörbaren Raum / Compositions for Audible Space: Die frühe elektroakustische Musik und ihre Kontexte / The Early Electroacoustic Music and its ContextsDa EverandKompositionen für hörbaren Raum / Compositions for Audible Space: Die frühe elektroakustische Musik und ihre Kontexte / The Early Electroacoustic Music and its ContextsNessuna valutazione finora

- Electrifying Music ColDocumento16 pagineElectrifying Music ColMalcolm WilsonNessuna valutazione finora

- David Tudor's Realization of John Cage's Variations IIDocumento18 pagineDavid Tudor's Realization of John Cage's Variations IIfdjaklfdjka100% (1)

- Songs, Society and SemioticsDocumento189 pagineSongs, Society and SemioticsJune Maxwell100% (1)

- Blurred Lines - Practical and Theoretical Implications of A DAW-based PedagogyDocumento16 pagineBlurred Lines - Practical and Theoretical Implications of A DAW-based PedagogySpread The Love100% (1)

- De Nora, Tia. How Is Extra-Musical Meaning Possible, Music As A Place and Space For 'Work'Documento12 pagineDe Nora, Tia. How Is Extra-Musical Meaning Possible, Music As A Place and Space For 'Work'is taken ready100% (1)

- Cusik, S. 1994. Feminist Theory, Music Theory, and The Mind-Body ProblemDocumento21 pagineCusik, S. 1994. Feminist Theory, Music Theory, and The Mind-Body Problemis taken readyNessuna valutazione finora

- Blacking - J - How Musical Is ManDocumento36 pagineBlacking - J - How Musical Is ManCheyorium Complicatorum100% (2)

- M Logos I0002 A0018 02 PDFDocumento19 pagineM Logos I0002 A0018 02 PDF2413pagNessuna valutazione finora

- Equality and Diversity in Classical Music Report 2az518m PDFDocumento22 pagineEquality and Diversity in Classical Music Report 2az518m PDFThomas QuirkeNessuna valutazione finora

- Boulez Foucault Contemporary Music and The PublicDocumento6 pagineBoulez Foucault Contemporary Music and The PublicTommaso SettimiNessuna valutazione finora

- Words Music and Meaning PDFDocumento24 pagineWords Music and Meaning PDFkucicaucvecuNessuna valutazione finora

- Ecological Psychoacoustics 6 PDFDocumento60 pagineEcological Psychoacoustics 6 PDFcocoandcustNessuna valutazione finora

- What Is Sociological About MusicDocumento24 pagineWhat Is Sociological About MusicJunior Leme100% (1)

- (Approaches To Applied Semiotics (3) ) Eero Tarasti - Signs of Music - A Guide To Musical Semiotics-Mouton de Gruyter (2012)Documento232 pagine(Approaches To Applied Semiotics (3) ) Eero Tarasti - Signs of Music - A Guide To Musical Semiotics-Mouton de Gruyter (2012)Rafael Lima PimentaNessuna valutazione finora

- Agogic MapsDocumento78 pagineAgogic MapsK. Mille100% (1)

- Monahan 2011Documento23 pagineMonahan 2011James SullivanNessuna valutazione finora

- An Experimental Music TheoryDocumento10 pagineAn Experimental Music Theoryjuan martiNessuna valutazione finora

- Strzelecki (2010 ICMS) EvolutionarySemioticsOfMusicDocumento40 pagineStrzelecki (2010 ICMS) EvolutionarySemioticsOfMusicerbarium100% (1)

- Towards A Cultural Sociology of Popular MusicDocumento14 pagineTowards A Cultural Sociology of Popular MusicAxel JuárezNessuna valutazione finora

- Interview Barbara Haselbach ENGDocumento4 pagineInterview Barbara Haselbach ENGiuhalsdjvauhNessuna valutazione finora

- Music, Mind, and MeaningDocumento15 pagineMusic, Mind, and Meaningglobalknowledge100% (1)

- Oxford University Press The Musical QuarterlyDocumento12 pagineOxford University Press The Musical QuarterlyMeriç EsenNessuna valutazione finora

- Creativities Technologies and Media... ZDocumento358 pagineCreativities Technologies and Media... Zanammarquess96Nessuna valutazione finora

- Models of The Sign PeirceDocumento23 pagineModels of The Sign PeirceJoan Isma Ayu AstriNessuna valutazione finora

- Music and Spatial VerisimilitudeDocumento210 pagineMusic and Spatial VerisimilitudeAlan Ahued100% (1)

- Artistic Orchestration - Alan BelkinDocumento32 pagineArtistic Orchestration - Alan Belkin3d73e7e2Nessuna valutazione finora

- Atonality.: Serialism Twelve-Note CompositionDocumento19 pagineAtonality.: Serialism Twelve-Note CompositionYandi NdoyNessuna valutazione finora

- Sonic Virtuality Sound As Emergent Perception - Mark GrimshawDocumento169 pagineSonic Virtuality Sound As Emergent Perception - Mark GrimshawSasaNessuna valutazione finora

- CADOZ, Claude WANDERLEY, Marcelo. Gesture - Music PDFDocumento24 pagineCADOZ, Claude WANDERLEY, Marcelo. Gesture - Music PDFbrunomadeiraNessuna valutazione finora

- W. Weber - The History of The Musical CanonDocumento10 pagineW. Weber - The History of The Musical CanonCelina Adriana Brandão Pereira100% (1)

- Stockhausen - Mantra, Work No.32Documento8 pagineStockhausen - Mantra, Work No.32Romina S. RomayNessuna valutazione finora

- PDF EMS12 Emmerson Landy PDFDocumento12 paginePDF EMS12 Emmerson Landy PDFRafael Lima PimentaNessuna valutazione finora

- Richard Colwell - MENC Handbook of Research Methodologies-Oxford University Press (2006)Documento417 pagineRichard Colwell - MENC Handbook of Research Methodologies-Oxford University Press (2006)Nicolás Pérez100% (1)

- Sizhu Instrumental Music of South China Ethos, Theory and Practice 2008 PDFDocumento237 pagineSizhu Instrumental Music of South China Ethos, Theory and Practice 2008 PDFCosmin Postolache100% (2)

- My Approach: Carlos Salzedo, Modern Study of The Harp, 6Documento1 paginaMy Approach: Carlos Salzedo, Modern Study of The Harp, 6godieggNessuna valutazione finora

- Psychology of MusicDocumento24 paginePsychology of Musicq12wertyNessuna valutazione finora

- Philip Tagg Musics Meanings A Modern Musicology For Non Musos New York Huddersfield Mass Media Music Scholars Press 2012Documento6 paginePhilip Tagg Musics Meanings A Modern Musicology For Non Musos New York Huddersfield Mass Media Music Scholars Press 2012신현준Nessuna valutazione finora

- Music of The Classical PeriodDocumento4 pagineMusic of The Classical Periodmcheche12Nessuna valutazione finora

- Liszt On Berlioz's Harold SymphonyDocumento9 pagineLiszt On Berlioz's Harold SymphonyHannah CNessuna valutazione finora

- The University of Chicago PressDocumento33 pagineThe University of Chicago PressmargotsalomeNessuna valutazione finora

- Complicating, Considering, and Connecting Music EducationDa EverandComplicating, Considering, and Connecting Music EducationNessuna valutazione finora

- Why We Love Repetition in Music (Transcrição) PDFDocumento1 paginaWhy We Love Repetition in Music (Transcrição) PDFaugustomarocloNessuna valutazione finora

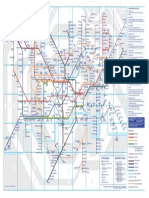

- Tube Map May 2015Documento1 paginaTube Map May 2015BladyPanopticoNessuna valutazione finora

- Isopleth - Vardan OvsepianDocumento1 paginaIsopleth - Vardan OvsepianBladyPanoptico100% (2)

- Nicanor Abelardo PDFDocumento6 pagineNicanor Abelardo PDFLucasEscaiGualquerNessuna valutazione finora

- CavatinaDocumento5 pagineCavatinaKirt Vasquez MangandiNessuna valutazione finora

- Education in LatinoamericaDocumento287 pagineEducation in LatinoamericaBladyPanopticoNessuna valutazione finora

- FoatingISlandsWALTZ PDFDocumento5 pagineFoatingISlandsWALTZ PDFLiviu AvramNessuna valutazione finora

- Music and Memory An IntroductionDocumento292 pagineMusic and Memory An IntroductionCharles Parker100% (3)

- Tube Map May 2015Documento1 paginaTube Map May 2015BladyPanopticoNessuna valutazione finora

- 16th Rest TimeDocumento1 pagina16th Rest TimeBladyPanopticoNessuna valutazione finora

- Schillinger's AccebaDocumento17 pagineSchillinger's AccebaBladyPanopticoNessuna valutazione finora

- 16th Rest TimeDocumento1 pagina16th Rest TimeBladyPanopticoNessuna valutazione finora

- Six Four One Five:The Sensitive Female Chord Progression: Song ListDocumento20 pagineSix Four One Five:The Sensitive Female Chord Progression: Song ListBladyPanopticoNessuna valutazione finora

- Which Mean Do You Mean? An Exposition On MeansDocumento69 pagineWhich Mean Do You Mean? An Exposition On MeansalexandranalisaNessuna valutazione finora

- Schillinger's EcentriadeDocumento2 pagineSchillinger's EcentriadeBladyPanopticoNessuna valutazione finora

- Harmonic Sequences Reordering I V Vi IVDocumento1 paginaHarmonic Sequences Reordering I V Vi IVBladyPanopticoNessuna valutazione finora

- Organised Sound 4Documento21 pagineOrganised Sound 4theperfecthumanNessuna valutazione finora

- Organised SoundDocumento10 pagineOrganised SoundtheperfecthumanNessuna valutazione finora

- IMSLP308575-PMLP498921-Ibert - Entracte Flute or Violin and GuitarDocumento6 pagineIMSLP308575-PMLP498921-Ibert - Entracte Flute or Violin and GuitarFrancesco CirilloNessuna valutazione finora

- IMSLP308575-PMLP498921-Ibert - Entracte Flute or Violin and GuitarDocumento6 pagineIMSLP308575-PMLP498921-Ibert - Entracte Flute or Violin and GuitarFrancesco CirilloNessuna valutazione finora

- Organised SoundDocumento10 pagineOrganised SoundtheperfecthumanNessuna valutazione finora

- Pretty Good YearDocumento1 paginaPretty Good YearBladyPanopticoNessuna valutazione finora

- Keyboard With Letters PDFDocumento1 paginaKeyboard With Letters PDFJoNessuna valutazione finora

- IMSLP308575-PMLP498921-Ibert - Entracte Flute or Violin and GuitarDocumento6 pagineIMSLP308575-PMLP498921-Ibert - Entracte Flute or Violin and GuitarFrancesco CirilloNessuna valutazione finora

- Organised SoundDocumento10 pagineOrganised SoundtheperfecthumanNessuna valutazione finora

- Tapping Book Fico de CastroDocumento25 pagineTapping Book Fico de Castromikeltxu21100% (8)

- Jazz Method Guitar - Comping Partitions)Documento48 pagineJazz Method Guitar - Comping Partitions)wakanabeotai100% (8)

- Brief Musica Por MetroDocumento5 pagineBrief Musica Por MetroBladyPanopticoNessuna valutazione finora

- Table of Pitch Class SetsDocumento14 pagineTable of Pitch Class SetsBladyPanopticoNessuna valutazione finora

- Pitch Class SetsDocumento15 paginePitch Class SetsGEC1227100% (1)

- BCECE Counselling ScheduleDocumento1 paginaBCECE Counselling ScheduleSaurav Kumar SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- Regulations and Manuals 2013Documento42 pagineRegulations and Manuals 2013anoojakaravaloorNessuna valutazione finora

- Aruna ReddyDocumento14 pagineAruna ReddyVinay ChagantiNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 1 Function Lesson Plan First Year BacDocumento2 pagineUnit 1 Function Lesson Plan First Year BacMohammedBaouaisseNessuna valutazione finora

- CBSE Mid Term Exam InstructionsDocumento1 paginaCBSE Mid Term Exam InstructionsSamNessuna valutazione finora

- Clozing in On Oral Errors: Glenn T. GainerDocumento5 pagineClozing in On Oral Errors: Glenn T. GainerBarbara HernandezNessuna valutazione finora

- Realism: Subjective Long QuestionsDocumento11 pagineRealism: Subjective Long QuestionsAnam RanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Fes-School Action Plan Sy2019-2020 Updated01Documento21 pagineFes-School Action Plan Sy2019-2020 Updated01api-250691083Nessuna valutazione finora

- K Theuer Promotion Letter of Support FinalDocumento2 pagineK Theuer Promotion Letter of Support Finalapi-268700252Nessuna valutazione finora

- Post Doctoral Research Fellow-Research Fellow - PDDocumento5 paginePost Doctoral Research Fellow-Research Fellow - PDpauloquioNessuna valutazione finora

- Rancangan Pengajaran Harian Sains Kanak-Kanak Pendidikan KhasDocumento2 pagineRancangan Pengajaran Harian Sains Kanak-Kanak Pendidikan KhasnadiaburnNessuna valutazione finora

- Types of Kidney Stones and Their SymptomsDocumento19 pagineTypes of Kidney Stones and Their SymptomsramuNessuna valutazione finora

- Dubai Application FormDocumento13 pagineDubai Application Formishq ka ain100% (1)

- Nift Synopsis PDFDocumento9 pagineNift Synopsis PDFVerma Tarun75% (4)

- Something Is Wrong-CurriculumDocumento382 pagineSomething Is Wrong-Curriculumfuckoffff1234Nessuna valutazione finora

- Dll-Week12-Creative WritingDocumento4 pagineDll-Week12-Creative WritingCarna San JoseNessuna valutazione finora

- Benchmarking E-Learning Phase 1 BELA OverviewDocumento10 pagineBenchmarking E-Learning Phase 1 BELA OverviewPaul BacsichNessuna valutazione finora

- The Lincoln University: International Graduate Admission Application and Acceptance InformationDocumento7 pagineThe Lincoln University: International Graduate Admission Application and Acceptance Informationapi-281064364Nessuna valutazione finora

- Competency Assessment Summary ResultsDocumento1 paginaCompetency Assessment Summary ResultsLloydie Lopez100% (1)

- Edcn 103 Micro StudyDocumento17 pagineEdcn 103 Micro StudyYlesar Rood BebitNessuna valutazione finora

- Draft To Student Mse Oct 2014 - (Updated)Documento4 pagineDraft To Student Mse Oct 2014 - (Updated)Kavithrra WasudavenNessuna valutazione finora

- DMD 3062 - Final Year Project IDocumento10 pagineDMD 3062 - Final Year Project IShafiq KhaleedNessuna valutazione finora

- Is College For Everyone - RevisedDocumento5 pagineIs College For Everyone - Revisedapi-295480043Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Influence of Lecturers Service Quality On Student Satisfaction in English Subject For 2018 Batch of StudentsDocumento36 pagineThe Influence of Lecturers Service Quality On Student Satisfaction in English Subject For 2018 Batch of Studentsaninda kanefaNessuna valutazione finora

- Philippine Disaster Reduction and Management ActDocumento22 paginePhilippine Disaster Reduction and Management ActRhona Mae ArquitaNessuna valutazione finora

- Magna Carta For StudentsDocumento3 pagineMagna Carta For StudentsSarah Hernani DespuesNessuna valutazione finora

- BbauDocumento5 pagineBbaunandini CHAUHANNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson Plan: Religion and Revenge in "Hamlet"Documento2 pagineLesson Plan: Religion and Revenge in "Hamlet"kkalmes1992Nessuna valutazione finora

- Calculus Modules - Scope and SequenceDocumento13 pagineCalculus Modules - Scope and SequenceKhushali Gala NarechaniaNessuna valutazione finora

- 01 Main Idea, Main Topic, and MainDocumento9 pagine01 Main Idea, Main Topic, and MainnhidayatNessuna valutazione finora