Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Conformity of Commercial Oral Single Solid Unit Dose Packages in Hospital Pharmacy Practice

Caricato da

Sindhu WinataTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Conformity of Commercial Oral Single Solid Unit Dose Packages in Hospital Pharmacy Practice

Caricato da

Sindhu WinataCopyright:

Formati disponibili

International Journal for Quality in Health Care 2008; Volume 20, Number 3: pp.

206 210

Advance Access Publication: 12 March 2008

10.1093/intqhc/mzn001

Conformity of commercial oral single

solid unit dose packages in hospital

pharmacy practice

MAXIME THIBAULT, SONIA PROT-LABARTHE, JEAN-FRANCOIS BUSSIE`RES AND DENIS LEBEL

Department of Pharmacy, Unite de Recherche en Pratique Pharmaceutique, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Sainte-Justine, Montreal,

Quebec, Canada

Abstract

Background. There are limited published data on the labelling of single unit dose packages in hospitals.

Setting and participants. The study was conducted in three large hospitals (two adult and one paediatric) in the metropolitan

Montreal area, Quebec, Canada.

Objective. The objective is to evaluate the labelling of commercial oral single solid unit dose packages available in Canadian

urban hospital pharmacy practice.

Results. A total of 124 different unit dose packages were evaluated. The level of conformity of each criterion varied between

19 and 50%. Only 43% of unit dose packages provided an easy-to-detach system for single doses. Among the 14 manufacturers with three or more unit dose packages evaluated, eight (57%) had a conformity level less than 50%.

Conclusion. This study describes the conformity of commercial oral single solid unit dose packages in hospital pharmacy

practice in Quebec. A large proportion of unit dose packages do not conform to a set of nine criteria set out in the guidelines

of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists and the Canadian Society of Hospital Pharmacists.

Keywords: blister packaging, bulk, drug packaging and labeling, unit dose package

Introduction

In Canada and the USA, most hospital pharmacy

departments provide a daily unit dose drug distribution

system for inpatients [1, 2]. This distribution system has been

in wide use since the 1970s, and most publications related to

the implementation and evaluation of such systems were

published in the 1970s and 1980s [3 6]. A failure mode and

effects analysis to improve drug distribution suggests that the

percentage of opportunities during which any error occurred

was signicantly lower under the unit dose drug distribution

system [7].

The Institute of Medicine recommends the implementation of a unit dose drug distribution system as a medication

safety strategy to reduce errors in health care [8]. The

Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency has

issued guidelines for drug manufacturers. The International

Pharmaceutical Federation, the Institute for Safe Medication

Practices (ISMP), the American Society of Health-System

Pharmacists (ASHP) and the Canadian Society of Hospital

Pharmacists (CSHP) have published their statements and

guidelines on unit dose drug distribution [9 12]. According

to an ASHP statement on unit dose drug distribution, the

unit dose system may differ in form, depending on the

specic needs of the organization. However, the following

distinctive elements are basic to all unit dose systems: medications are contained in single unit packages; they are dispensed in as ready-to-administer form as possible; and for

Address reprint requests to: Jean-Francois Bussie`res; Department of Pharmacy, Unite de Recherche en Pratique

Pharmaceutique, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Sainte-Justine, Montreal, Quebec, Canada. E-mail: jf.bussieres@ssss.gouv.qc.ca

International Journal for Quality in Health Care vol. 20 no. 3

# The Author 2008. Published by Oxford University Press in association with the International Society for Quality in Health Care;

all rights reserved

206

Downloaded from by guest on April 3, 2015

Method. The study endpoint was the labelling conformity of each unit dose package for each criterion and overall for each

manufacturer. Complete labelling of unit dose packages should include the following information: (1) brand name, (2) international non-proprietary name or generic name, (3) dosage, (4) pharmaceutical form, (5) manufacturers name, (6) expiry

date, (7) batch number and (8) drug identication number. We also evaluated the ease with which a single unit dose package

is detached from a multiple unit dose package for quick, easy and safe use by pharmacy staff. Conformity levels were compared between brand-name and generic packages.

Conformity of unit dose packages

Methods

This is an observational study based on the visual inspection

of commercial oral single solid unit dose packages (hereafter

unit dose packages) available in three large hospitals in the

metropolitan Montreal area, Quebec, Canada. The three hospitals included are representative of major acute care settings

in Quebec (e.g. two large adult teaching hospitals with 637

and 571 beds each and one large mother-child university

hospital center with 500 beds). These hospitals purchase

drugs primarily through Approvisionnement Montreal, the

second largest drug-purchasing group in Canada. We identied all unit dose packages available in the 2006 2009 hospital purchasing agreement catalog. In July 2005, a pharmacy

research assistant visited three pharmacy departments in

order to locate, visually identify and evaluate all unit dose

packages in stock. Each hospital included in this study uses

an automated packaging system and has a daily unit dose

drug distribution system. Whenever listed in the agreement

catalog, the three hospitals purchase drugs in bulk to take

advantage of their automated medication system. Usually,

drugs purchased in unit dose packages are the only format

available. Based on our literature search, a group of three

pharmacists selected nine conformity criteria for unit dose

packages used in a daily hospital unit dose drug distribution

system. Complete labeling of unit dose packages should

include the following information: (1) brand name, (2) international nonproprietary name or generic name, (3) dosage,

(4) pharmaceutical form, (5) manufacturers name, (6) expiry

date, (7) batch number and (8) drug identication number.

We also evaluated the (9) ease with which a single unit dose

package is detached from a multiple unit dose package to

allow quick, easy and safe use by pharmacy staff. Based on

visual inspection, the conformity of each unit dose package

was assessed at each site visited and a digital photograph of

both sides of each unit dose package was taken. The study

endpoint was the labeling conformity of each unit dose

package for each criterion and overall for each manufacturer.

Conformity levels were compared between brand and generic

packages. The overall score of conformity per manufacturer

is the average of the score of conformity of each criterion

with a maximum of 100% (0 100% per criterion for a total

of nine criteria) for manufacturers with three or more drugs

evaluated. Data were entered in a spreadsheet (Microsoft

Excelw, Seattle, USA 2003). Statistical analysis was performed

with SPSS 15.0. (SPSS Inc., 2007). A P , 0.05 was considered signicant.

Results

A total of 374 unit dose packages were identied from

Approvisionnement-Montreals 2006 2009 catalog. A total

of 124 (33%) different unit dose packages were physically

located in the three hospitals visited for visual inspection.

Criterions conformity level varied from 19 to 50% for all

manufacturers, 13 to 42% for brand manufacturers and 41

207

Downloaded from by guest on April 3, 2015

most medications, not more than a 24-hour supply of doses

is delivered to or available at the patient-care area at any

time [9]. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare

Organizations standards require medications to be dispensed

in the most ready-to-administer form possible to minimize

opportunities for error [13].

According to the ASHP Technical Assistance Bulletin

on Single Unit and Unit Dose Packages of Drugs, drugs

packages must fulll four basic functions: identify their

contents completely and precisely, protect their contents

from deleterious environmental effects (e.g. photodecomposition), protect their contents from deterioration due

to handling (e.g. breakage and contamination) and permit

their contents to be used quickly, easily and safely [10].

According to CSHP guidelines for drug packaging and

labeling for manufacturers, a unit dose is a package that

contains a particular dose of drug ordered for a patient,

that is fully identied and that is ready for administration

directly from the package [12]. According to the guidelines,

the mandatory label components of each unit dose package

include the common or brand name for multiple active

ingredient products, strength, lot number, name of the manufacturer and expiry date. Furthermore, the unit dose

package must be able to be easily opened and the medication easily removed from the package to be administered

directly to the patient. Push-through packages should not

be used because the label is destroyed when the tablet

or capsule is removed. Interestingly, Cohen says that the

United States Pharmacopeia and Food and Drug

Administration should standardize the terminology used on

labels. Both single-use and single dose have been used on

containers labels to mean the same thing. He also says that

regardless of a products prescription or non-prescription

status, the name and exact strength should be present on

each pocket [referred to as a single unit dose package in our

text] of the blister strip. Whether or not the manufacturer

intends this, many nonprescription drugs are used in institutions as part of a unit dose dispensing system. [. . .] The

blisters can be cut and separated from one another, or the

drug name may be torn, making identication impossible

and contributing to subsequent errors if the product is relabeled extemporaneously [14].

Hospital pharmacists can buy drugs in bulk format or

unit dose packages. Bulk format contains unpacked drugs

that can be repacked by an automated medication dispensing

system (PacmedTM , AutomedTM , etc.). Multiple unit dose

packages are split (detached or cut) in single unit dose

packages. In an unknown proportion of cases, the labeling of

the detached single unit dose package is not complete for

safe medication use in hospitals. Any missing information on

a single unit dose package can lead to medication errors

(wrong medication, wrong patient, expired medication,

improper handling of a returned medication) [15 19].

There are limited published data on the labeling of single

unit dose packages in hospitals. The objective of this study is

to evaluate the labeling of commercial oral single solid unit

dose packages available in urban hospital pharmacy practice

in Canada.

M. Thibault et al.

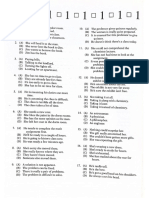

Table 1 Number and proportion of commercial oral single solid unit dose packages that conform to nine criteria (n 124)

and according to the type of manufacturer

Conformity criteria for unit dose

package

Number (proportion) of unit dose packages that conform to criteria

.................................................................................................................

All manufacturers

n (%)

Brand name

(n 97) n (%)

Generic

Comparison between

(n 27) n(%) brand and generic

manufacturers, P-value

.............................................................................................................................................................................

Presence of a brand name

Presence of international non proprietary

name

Presence of dosage

Presence of pharmaceutical form

Presence of manufacturers name

Presence of expiry date

Presence of batch/lot number

Presence of drug identication number

Ease with which single unit is detached

from multiple dose package

56(45)

53(43)

40(42)

34(35)

15(56)

22(82)

,0.28

,0.001

62(50)

24(19)

52(42)

53(43)

53(43)

32(26)

53(43)

40(41)

13(13)

31(32)

30(31)

30(31)

18(18)

33(34)

22(82)

11(41)

21(78)

23(85)

23(85)

15(56)

19(70)

,0.001

,0.001

,0.001

,0.001

,0.001

,0.001

,0.001

Conformity criteria

Cyclosporine 25 mg(Neoralw)

Novartis Pharma Canada, Inc.

Fenobrate 160 mg(Lipidil

Supraw) Fournier Pharma

.............................................................................................................................................................................

Presence of a brand name

Presence of international non proprietary name

Presence of dosage

Presence of pharmaceutical form

Presence of manufacturers name

Presence of expiry date

Presence of batch/lot number

Presence of drug identication number

Ease with which single unit is detached from

multiple dose package

Conform

Conform

Conform

Non conform

Conform

Conform

Conform

Non conform

Conform

to 85% for generic manufacturers (Table 1). Only 43% of

unit dose packages provided an easy-to-detach system for

single doses. Examples of conforming and nonconforming

unit dose packages are given in Table 2.

The lowest average score of conformity for all criteria for

a manufacturer (with three or more drugs evaluated) was 0%

(Leopharma and Servier) and the highest was 90% (Apotex).

Among the 14 manufacturers with three or more unit dose

208

Non conform

Non conform

Non conform

Non conform

Non conform

Non conform

Non conform

Non conform

Non conform

packages evaluated, eight (57%) had a conformity level less

than 50%. For all criteria, except the presence of a brand

name, the 27 unit dose packages from generic manufacturers

had a higher level of conformity than the 97 produced by

brand manufacturers (P 0.002). However, some brand

manufacturers had better scores than others (e.g. Merck

Frosst, Bayer). Apotex had the highest level of conformity

and the highest number of solid drug packages evaluated.

Downloaded from by guest on April 3, 2015

Table 2 Examples of criteria conformity of commercial oral single solid unit dose packages

Conformity of unit dose packages

Discussion

209

Downloaded from by guest on April 3, 2015

This study describes the conformity of commercial oral

single solid unit dose packages in hospital pharmacy practice

in Quebec. A large proportion of unit doses packages do not

conform to a set of nine criteria set out in the guidelines of

the ASHP and the CSHP. In the Canadian context, the low

conformity of labeling of unit dose packages can be partly

explained by the fact that the Canadian Food and Drug Act

regulates outside and inside labeling of multiple dose

packages, but not specically single unit dose packages that

can be detached and used in hospital settings.

Our study indicates that for all criteria, except for the

presence of a brand name, unit dose packages from generic

manufacturers had a higher level of conformity than those

produced by the brand-name manufacturers. Based upon

our hospital group purchasing activities, we postulate that

the generic industry is more pharmacy-oriented when it

comes to differentiating their products and fullling hospital needs.

In a survey of US state boards of pharmacy in 2003 pertaining to the status of multiple dose packages (also called

blister packages), approximately two-thirds of respondents

believed that multiple dose packaging would improve efciency, reduce errors in dispensing, improve patient compliance and increase opportunities for patient counseling in

community pharmacy practice [20]. Supporters of multiple

unit dose packages have mentioned its potential positive

effect on patient compliance. In a community setting, multiple unit dose packages can also contribute to reinforce the

brand-name identity of a drug. Although the use of multiple

unit dose packages can improve efciency for retail pharmacy activities, hospital pharmacists have different needs and

there are no published reports describing the difculties

inherent to the nonconformity of single unit dose packages

in hospital settings.

In Europe, the majority of drugs are packaged in multiple

unit dose packages for retail and hospital settings. The

limited penetration of unit dose drug distribution systems in

hospitals has not exerted any signicant pressure on manufacturers to maintain a bulk format available for nominal

daily drug distribution. Indeed, problems with multiple unit

dose packages have not been reported in the European

context. Interestingly, some companies have developed

deblistering machines (e.g. www.pentapackna.com) to unpack

multiple unit dose packages for automated medication

systems. Alternatively, manual deblistering can be processed

by pharmacy staff, although it is time consuming and

requires cutters, and there is a risk of staff injury, as some

packages can be edged. Aside from the inherent risk of

injury, this process is unproductive and could lead to dispensing doses with incomplete relevant information or expired

drugs if the unit dose package, when detached from the multiple unit dose package, does not conform.

There are few published data regarding the impact of the

labeling of single unit dose packages in hospitals. Medication

errors in hospitals have received considerable attention, as

they entail signicant mortality, morbidity and additional

healthcare costs. In the Canadian Adverse Events Study [21],

the overall incidence of adverse events was 7.5%. Of the 360

events identied, 85 were drug or uid related. Medication

errors can occur from prescribing (49 68%) or distributing

and administering drugs (9 51%) [22]. The hospital pharmacist is best placed to oversee the quality of the entire drug

distribution circuit, from prescribing, selecting and dispensing

through to preparing and administering drugs [15]. Drug

labeling is an important component of the drug distribution

circuit to avoid medication errors in the pharmacy or at the

bedside. Kenagy et al. state that the ISMP receives 1200

1500 reports of serious complications resulting from the use

of drugs. Approximately 25% of these are related to name

confusion and another 25% to labeling and packaging issues

[23]. The authors point out that the ISMP estimates only 1

2% of events are reported. In their 2001 medication error

report to the Food and Drug Administration, Thomas and

Holquist calculate that 20% of medication errors are related

to labeling and 6% to packaging and design [24]. In a review

published by Berman, up to 25% of all medication errors are

attributed to name confusion and 33% to packaging and/or

labeling confusion [19]. In annual review about the labeling

and packaging of drugs, La Revue Prescrire states that more

than 90% of multiple unit dose packages (blister packs) are

not appropriate for single unit doses [25].

The National Coordination Council for Medication Error

Reporting and Prevention has made a series of recommendations for medication labeling and packaging that may help

to reduce the incidence of medication errors. Among these

recommendations, collaboration is called for among industry,

regulators, standard-setters, healthcare professionals, healthcare organizations and patients to facilitate the design of

packaging and labeling to help minimize errors. Another

report indicated that confusing, inaccurate or incomplete

drug labeling contributed to 21% of potential or actual

medication errors reported through the US Pharmacopeia

Practitioners Reporting Network over a one year period

[18]. Very few cases of errors related to labeling and packaging have been published. For example, Guchelaar et al.

reported a case in which the patient had been given a

double dose of valaciclovir due to the ambiguous labeling of

a commercial drug [15]. Pathak et al. reported confusion

between amiodarone and acebutolol by confusing generic

drug blisters that often have the same appearance to minimize costs [16].

This study does have its limitations. We evaluated a selection of all commercial oral single solid unit dose packages

located in three large hospitals of a metropolitan area in

Canada. A representative sample including all provinces

would be more appropriate, although the same drugs are

available across the country. The discrepancy observed

between the number of unit dose packages listed in the hospital purchasing agreement catalog (n 374 unit dose

packages) and the number of packages included in this study

(n 124) can be explained by local hospital decisions not to

purchase some of the drugs and having other formats or

M. Thibault et al.

molecules listed in their hospital formulary. Moreover, the

results apply to the Canadian context and may differ in other

jurisdictions, as labeling and marketing policies differ from

country to country. This study did not evaluate the conformity of unit dose packages produced, repacked and labeled

by pharmacy departments through their in-house systems.

This study describes the emergence of a nonconforming

format that requires repackaging in hospital pharmacy practice and that could be avoided through better collaboration

between pharmacy manufacturers and hospital pharmacists.

Conclusion

This study describes the conformity of commercial oral

single solid unit dose packages in hospital pharmacy practice

in Quebec. A large proportion of unit doses packages do not

conform to a set of nine criteria set out in the guidelines of

the ASHP and the CSHP.

9. ASHP. ASHP Statement on unit dose drug distribution. Am J

Hosp Pharm 1989;46:2346.

10. ASHP. ASHP Technical assistance bulletin on single unit

and unit dose packages of drugs. Am J Hosp Pharm 1985;

42:378 9.

11. ASHP. ASHP Technical assistance bulletin on hospital drug

distribution and control. Am J Hosp Pharm 1980;37:1097 103.

12. Guidelines for drug packaging and labelling for manufacturers.

2001. http://www.cshp.ca/productsServices/ofcialPublications/

index_e.asp (9 Jan 2008, date last accessed).

13. JCAHO. Comprehensive accreditation manual for hospitals

the ofcial handbook: Oak Brook Terrace III, 1998.

14. Cohen M. Medication Errors, 2nd Edn. Washington: American

Pharmacists Association, 2007.

15. Guchelaar HJ, Kalmeijer MD, Jansen ME. Medication error

due to ambiguous labelling of a commercial product. Pharm

World Sci 2004;26:10 1.

16. Pathak A, Senard JM, Bujaud T et al. Medication error caused

by confusing drug blisters. Lancet 2004;363:2142.

References

2. Hospital Pharmacy in Canada. 2005/06 Annual Report. Ethics

in Hospital Pharmacy. 2007. (Accessed 8 January 2007, at www.

lillyhospitalsurvey.ca.)

3. Means BJ, Derewicz HJ, Lamy PP. Medication errors in a multidose and a computer-based unit dose drug distribution system.

Am J Hosp Pharm 1975;32:18691.

4. OBrodovich M, Rappaport P. A study pre and post unit dose

conversion in a pediatric hospital. Can J Hosp Pharm

1991;44:5 15, 50.

5. Gaucher M, Greer M. A nursing evaluation of unit dose and

computerized medication administration records. Can J Hosp

Pharm 1992;45:145 50.

6. ASHP. Medication distribution system. In: Handbook of institutional pharmacy practice. 4th edn. Bethesda: American Society of

Health-System Pharmacists, Inc.

7. McNally KM, Page MA, Sunderland VB. Failure-mode and

effects analysis in improving a drug distribution system. Am J

Health Syst Pharm 1997;54:171 7.

8. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MSE. To err is human.

Building a safer health system. Committee on Quality of Health

Care in America. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press;

2000.

210

18. Orser B. Reducing medication errors. Canadian Medical

Association Journal 2000;162:1150 6.

19. Berman A. Reducing medication errors through naming, labeling, and packaging. J Med Syst 2004;28:9 29.

20. Szeinbach SL, Baron M, Guschke T, Torkilson EA. Survey of

state requirements for unit-of-use packaging. Am J Health Syst

Pharm 2003;60:1863 6.

21. Baker GR, Norton PG, Flintoft V et al. The Canadian Adverse

Events Study: the incidence of adverse events among hospital

patients in Canada. Cmaj 2004;170:1678 86.

22. Hepler C, Segal R. Preventing Medication Errors and Improving Drug

Therapy OutcomesA Management systems approach. Boca Raton:

CRC Press, 2003.

23. Kenagy JW, Stein GC. Naming, labeling, and packaging of

pharmaceuticals. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2001;58:2033 41.

24. Med error reports to FDA show a mixed bag. 2001. http://

www.fda.gov/cder/drug/MedErrors/mixed.pdf (9 Jan 2008,

date last accessed).

25. Packaging of pharmaceuticals: still too many dangers but

several encouraging initiatives. Prescrire Int 2007;16:126 8.

Accepted for publication 25 January 2008

Downloaded from by guest on April 3, 2015

1. Pedersen CA, Schneider PJ, Scheckelhoff DJ. ASHP national

survey of pharmacy practice in hospital settings: dispensing

and administration2005. Am J Health Syst Pharm

2006;63:327 45.

17. Practitioners Reporting News: Cases submitted to MER

Misleading labeling; processing problem; Potential abbreviation

error; poor pahckaging design. 2004. http://www.usp.org/hqi/

patientSafety/newsletters/practitioner

ReportingNews/prn

1132004-03-31.html (12 June 2007, date last accessed).

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Analytical Chemistry for Assessing Medication AdherenceDa EverandAnalytical Chemistry for Assessing Medication AdherenceNessuna valutazione finora

- mzw111 1 PDFDocumento6 paginemzw111 1 PDFsmwaruNessuna valutazione finora

- Hospital Formulary DR MotghareDocumento50 pagineHospital Formulary DR MotghareNaveen Kumar50% (2)

- Hospital FormularyDocumento3 pagineHospital FormularyDeepthi Gopakumar100% (3)

- AutomatedDocumento17 pagineAutomatedapi-413377677Nessuna valutazione finora

- Shelf Life PDFDocumento8 pagineShelf Life PDFMihir DixitNessuna valutazione finora

- Medication Safety Alerts: David UDocumento3 pagineMedication Safety Alerts: David UVina RulinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Aps Uk Pharm Sci Poster 2014 PDFDocumento1 paginaAps Uk Pharm Sci Poster 2014 PDFapi-266268510Nessuna valutazione finora

- Fmea DispensingDocumento13 pagineFmea DispensingFARMASI KLINISNessuna valutazione finora

- National Medication Safety Guidelines Manual FinalDocumento29 pagineNational Medication Safety Guidelines Manual FinalNur HidayatiNessuna valutazione finora

- Sea 35 PDFDocumento3 pagineSea 35 PDFEvianti Dwi AgustinNessuna valutazione finora

- Conciliação 007 PDFDocumento14 pagineConciliação 007 PDFIzabella WebberNessuna valutazione finora

- Fs 2Documento13 pagineFs 2Muhamad Taufiq AliNessuna valutazione finora

- How Stable Are Medicines Moved From Original Packs Into Compliance AidsDocumento7 pagineHow Stable Are Medicines Moved From Original Packs Into Compliance AidsMaruska MoratoNessuna valutazione finora

- Medication Errors:: Experience of The United States Pharmacopeia (USP)Documento6 pagineMedication Errors:: Experience of The United States Pharmacopeia (USP)cicaklomenNessuna valutazione finora

- Daniel Wood Christopher Gregory: Understanding GenericsDocumento9 pagineDaniel Wood Christopher Gregory: Understanding Genericsniravpharma21Nessuna valutazione finora

- Drug Administration Errors in Hospital Inpatients: A Systematic ReviewDocumento11 pagineDrug Administration Errors in Hospital Inpatients: A Systematic ReviewPardon MeNessuna valutazione finora

- Running Head: Analysis of Automated Dispensing Cabinets 1Documento16 pagineRunning Head: Analysis of Automated Dispensing Cabinets 1api-413318865Nessuna valutazione finora

- Barriers To The Implementation of Pharmaceutical CDocumento8 pagineBarriers To The Implementation of Pharmaceutical CRoaaNessuna valutazione finora

- Drug Utilization ReviewDocumento7 pagineDrug Utilization ReviewFaizaNadeemNessuna valutazione finora

- 2009 Drug InformationDocumento8 pagine2009 Drug InformationAnggioppleNessuna valutazione finora

- Evaluation of Drug Administration Errors in A Teaching HospitalDocumento8 pagineEvaluation of Drug Administration Errors in A Teaching Hospitalmatin5Nessuna valutazione finora

- Evaluation of Pharmaceutical InventoryDocumento16 pagineEvaluation of Pharmaceutical Inventorynanguh2004Nessuna valutazione finora

- Pharmaco Economic Evaluation in Polypharmacy of Elder Population: A Prospective Observational StudyDocumento12 paginePharmaco Economic Evaluation in Polypharmacy of Elder Population: A Prospective Observational StudyManeesha KodipelliNessuna valutazione finora

- Compounding and DispensingDocumento9 pagineCompounding and DispensingElida Rizki MhNessuna valutazione finora

- Potential Strategies WasteDocumento14 paginePotential Strategies Wastetsholofelo motsepeNessuna valutazione finora

- Preventing Medication ErrorsDocumento26 paginePreventing Medication ErrorsmrkianzkyNessuna valutazione finora

- Who Atc DDDDocumento31 pagineWho Atc DDDYuanita PurnamiNessuna valutazione finora

- Pharmacopolitics, Implications and Implementation in Clinical StudiesDocumento3 paginePharmacopolitics, Implications and Implementation in Clinical StudiesNantarat KengkeatchaiNessuna valutazione finora

- Drug Normalisation DissertationDocumento8 pagineDrug Normalisation DissertationUK100% (1)

- Artigo Sobre TromboembolismoDocumento8 pagineArtigo Sobre TromboembolismoJohnattanNessuna valutazione finora

- SAQ127 Indicators 3.2Documento4 pagineSAQ127 Indicators 3.2Edi Uchiha SutarmantoNessuna valutazione finora

- Safe Administrations of Medications (Draft Chapter)Documento74 pagineSafe Administrations of Medications (Draft Chapter)Caleb FellowesNessuna valutazione finora

- Jurnal Pharmaceutical Care 3Documento8 pagineJurnal Pharmaceutical Care 3Sindi CarenaNessuna valutazione finora

- Biology Project On Ai in MedicineDocumento10 pagineBiology Project On Ai in Medicinejapmansingh45678Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Epidemiology of Medication Errors: The Methodological DifficultiesDocumento7 pagineThe Epidemiology of Medication Errors: The Methodological DifficultiesgabyvaleNessuna valutazione finora

- Session 10 Essential Medicine SelectionDocumento23 pagineSession 10 Essential Medicine SelectionPhaimNessuna valutazione finora

- Conciliação 009 Ok PDFDocumento19 pagineConciliação 009 Ok PDFIzabella WebberNessuna valutazione finora

- National Medication Safety Guidelines Manual: June 2013Documento29 pagineNational Medication Safety Guidelines Manual: June 2013enik praNessuna valutazione finora

- 4.applications of Computers in PharmacyDocumento48 pagine4.applications of Computers in PharmacyOmkar KaleNessuna valutazione finora

- Hsahagon Methotrexate TherapyDocumento14 pagineHsahagon Methotrexate Therapyapi-648597244Nessuna valutazione finora

- IIR - IJDMTA - 15 - 001 Final Paper PDFDocumento6 pagineIIR - IJDMTA - 15 - 001 Final Paper PDFInternational Journal of Computing AlgorithmNessuna valutazione finora

- Practice Standard Safety & QualityDocumento2 paginePractice Standard Safety & Qualityssreya80Nessuna valutazione finora

- Pharmacovigilance and Its Importance in Drug Regulation: An OverviewDocumento16 paginePharmacovigilance and Its Importance in Drug Regulation: An OverviewSarah ApriliaNessuna valutazione finora

- Dispensing MedicinesDocumento80 pagineDispensing Medicinesfa6oom1994Nessuna valutazione finora

- Phos 313 - Activity No 7 PhosDocumento6 paginePhos 313 - Activity No 7 PhosDIANA CAMILLE CARITATIVONessuna valutazione finora

- Evidence Based Practice Medication ErrorsDocumento6 pagineEvidence Based Practice Medication Errorsapi-302591810Nessuna valutazione finora

- Dispensing EnvironmentDocumento72 pagineDispensing EnvironmentLeo Gonzales Calayag100% (1)

- Pharmaceutical MarketingDocumento6 paginePharmaceutical MarketingFazal MalikNessuna valutazione finora

- Research Paper Medication ErrorsDocumento6 pagineResearch Paper Medication Errorsegxtc6y3100% (1)

- Jurnal PsDocumento19 pagineJurnal PsIkeSintiaSuciNessuna valutazione finora

- Consumer Generics Australia IjppDocumento8 pagineConsumer Generics Australia IjppArief Bin IbrahimNessuna valutazione finora

- PharmacoepidemiologyDocumento2 paginePharmacoepidemiologyFyrrNessuna valutazione finora

- Medication SafetyDocumento5 pagineMedication SafetyJohn CometNessuna valutazione finora

- Evaluation of Drug Administration ErrorsDocumento8 pagineEvaluation of Drug Administration ErrorsAchmad Indra AwaluddinNessuna valutazione finora

- ASHP Statement On UDDDocumento1 paginaASHP Statement On UDDZamrotul IzzahNessuna valutazione finora

- Drug Utilization Review PDFDocumento7 pagineDrug Utilization Review PDFDimas CendanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Drug Development The Journey of A Medicine From Lab To ShelfDocumento6 pagineDrug Development The Journey of A Medicine From Lab To ShelfClaudia NovăceanNessuna valutazione finora

- Bioequivalence Studies - A Regulatory PerspectiveDocumento12 pagineBioequivalence Studies - A Regulatory Perspectivebhanu99100% (2)

- Managing Medicine SelectionDocumento25 pagineManaging Medicine SelectionShoaib BiradarNessuna valutazione finora

- 500 MFCC - Toefl TestDocumento19 pagine500 MFCC - Toefl TestSindhu WinataNessuna valutazione finora

- WhatsApp Image 2021-09-30 at 21.52.23 (2) - DikonversiDocumento1 paginaWhatsApp Image 2021-09-30 at 21.52.23 (2) - DikonversiSindhu WinataNessuna valutazione finora

- 78 Toefl Test - MFCCDocumento16 pagine78 Toefl Test - MFCCSindhu WinataNessuna valutazione finora

- 71 Answer TOEFL TEST - MFCCDocumento5 pagine71 Answer TOEFL TEST - MFCCSindhu WinataNessuna valutazione finora

- Kode BarangDocumento38 pagineKode BarangSindhu WinataNessuna valutazione finora

- 75 Toefl Test - MFCCDocumento19 pagine75 Toefl Test - MFCCSindhu WinataNessuna valutazione finora

- Stock 6 SepDocumento15 pagineStock 6 SepSindhu WinataNessuna valutazione finora

- Daftar Obat PrekursorDocumento2 pagineDaftar Obat PrekursorSindhu Winata0% (1)

- How To Upgrade DVR IPC Automatically Via HIKTOOLDocumento1 paginaHow To Upgrade DVR IPC Automatically Via HIKTOOLSindhu WinataNessuna valutazione finora

- Ethical & Otc 20 - 25 September 2021Documento9 pagineEthical & Otc 20 - 25 September 2021Sindhu WinataNessuna valutazione finora

- 02 AddendumDocumento4 pagine02 AddendumSindhu WinataNessuna valutazione finora

- The Application of Forecasting Techniques: A Case Study of Chemical Fertilizer StoreDocumento7 pagineThe Application of Forecasting Techniques: A Case Study of Chemical Fertilizer StoreSindhu WinataNessuna valutazione finora

- Drug InteractionsDocumento33 pagineDrug InteractionsBindira MaharjanNessuna valutazione finora

- 09 Feb 2021 FDA Citizen - S Charter CDRR - CPR - 02 February 2020Documento276 pagine09 Feb 2021 FDA Citizen - S Charter CDRR - CPR - 02 February 2020Raeanne Sabado BangitNessuna valutazione finora

- NDC Format For Billing PADDocumento3 pagineNDC Format For Billing PADShantkumar ShingnalliNessuna valutazione finora

- Study Timeline ExampleDocumento1 paginaStudy Timeline ExamplePamela WolfeNessuna valutazione finora

- Lab 1 (Lمحاضرات العملي)Documento20 pagineLab 1 (Lمحاضرات العملي)RaghdaNessuna valutazione finora

- PPTDocumento3 paginePPTRani RamadaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Pharma - Fundamental Concepts of Pharmacology 1Documento96 paginePharma - Fundamental Concepts of Pharmacology 1gelean payodNessuna valutazione finora

- Indian Council of Medical ResearchDocumento26 pagineIndian Council of Medical ResearchkunalNessuna valutazione finora

- Biofar&farmakokinetikDocumento34 pagineBiofar&farmakokinetikYayuk Abay TambunanNessuna valutazione finora

- Pharmacokinetics PDFDocumento14 paginePharmacokinetics PDFLea PesiganNessuna valutazione finora

- Board of Technical Education, Uttar Pradesh, Lucknow: Branch Code QP - No. Semester Code Subject Date Timings EffectiveDocumento1 paginaBoard of Technical Education, Uttar Pradesh, Lucknow: Branch Code QP - No. Semester Code Subject Date Timings EffectiveSurya pratap YadavNessuna valutazione finora

- The Biopharmaceutical Classification System (BCS) : DR Mohammad IssaDocumento24 pagineThe Biopharmaceutical Classification System (BCS) : DR Mohammad IssaDevi IndrianiNessuna valutazione finora

- GUI - FINAL - Determining Whether To Submit An ANDA or A 505 (B) (2) Application - Published - May2019Documento17 pagineGUI - FINAL - Determining Whether To Submit An ANDA or A 505 (B) (2) Application - Published - May2019Proschool HyderabadNessuna valutazione finora

- Biosimilar Drugs 1Documento5 pagineBiosimilar Drugs 1Refhany AfidhaNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 - Introduction To Clinical Research & Phases in CRDocumento25 pagine1 - Introduction To Clinical Research & Phases in CRAyush AhujaNessuna valutazione finora

- Kajian Hukum Peran Apoteker Dalam Saintifikasi JamuDocumento6 pagineKajian Hukum Peran Apoteker Dalam Saintifikasi JamuNavisa HaifaNessuna valutazione finora

- Understanding Chemist Labels: Name: Class: DateDocumento2 pagineUnderstanding Chemist Labels: Name: Class: DateMarta VladNessuna valutazione finora

- In Vitro in Vivo: CorrelationsDocumento15 pagineIn Vitro in Vivo: CorrelationsWadood HassanNessuna valutazione finora

- Beyond Use DateDocumento56 pagineBeyond Use DateDa Chan100% (1)

- MCQ PharmacokineticsDocumento10 pagineMCQ PharmacokineticsHarshit Sharma100% (1)

- Jurnal BisoprololDocumento10 pagineJurnal Bisoprololindrias pitalokaNessuna valutazione finora

- Pharmaco MetricsDocumento16 paginePharmaco Metrics88AKKNessuna valutazione finora

- BrochureDocumento8 pagineBrochureDr. Anil LandgeNessuna valutazione finora

- Food-Drug InteractionsDocumento5 pagineFood-Drug InteractionsDwi SrijonoNessuna valutazione finora

- Art2 - Design - Req, 07 OricDocumento7 pagineArt2 - Design - Req, 07 OricAfifa ZeeshanNessuna valutazione finora

- Route of Drug AdministrationDocumento14 pagineRoute of Drug AdministrationGangaram Saini100% (1)

- Hospital FormularyDocumento18 pagineHospital FormularyNikki Chauhan75% (4)

- Pharma Case Study DeckDocumento26 paginePharma Case Study DeckKoushik SircarNessuna valutazione finora

- Drug DiscoveryDocumento26 pagineDrug DiscoverySajanMaharjanNessuna valutazione finora

- The Development and Validation of A Dissolution Method For Clomipramine Solid Dosage FormsDocumento7 pagineThe Development and Validation of A Dissolution Method For Clomipramine Solid Dosage FormsBad Gal Riri BrunoNessuna valutazione finora

- Healing Your Aloneness: Finding Love and Wholeness Through Your Inner ChildDa EverandHealing Your Aloneness: Finding Love and Wholeness Through Your Inner ChildValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (9)

- Allen Carr's Easy Way to Quit Vaping: Get Free from JUUL, IQOS, Disposables, Tanks or any other Nicotine ProductDa EverandAllen Carr's Easy Way to Quit Vaping: Get Free from JUUL, IQOS, Disposables, Tanks or any other Nicotine ProductValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (31)

- Save Me from Myself: How I Found God, Quit Korn, Kicked Drugs, and Lived to Tell My StoryDa EverandSave Me from Myself: How I Found God, Quit Korn, Kicked Drugs, and Lived to Tell My StoryNessuna valutazione finora

- Breaking Addiction: A 7-Step Handbook for Ending Any AddictionDa EverandBreaking Addiction: A 7-Step Handbook for Ending Any AddictionValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (2)

- Little Red Book: Alcoholics AnonymousDa EverandLittle Red Book: Alcoholics AnonymousValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (20)

- Self-Love Affirmations For Deep Sleep: Raise self-worth Build confidence, Heal your wounded heart, Reprogram your subconscious mind, 8-hour sleep cycle, know your value, effortless healingsDa EverandSelf-Love Affirmations For Deep Sleep: Raise self-worth Build confidence, Heal your wounded heart, Reprogram your subconscious mind, 8-hour sleep cycle, know your value, effortless healingsValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (6)

- Allen Carr's Quit Drinking Without Willpower: Be a happy nondrinkerDa EverandAllen Carr's Quit Drinking Without Willpower: Be a happy nondrinkerValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (8)

- Guts: The Endless Follies and Tiny Triumphs of a Giant DisasterDa EverandGuts: The Endless Follies and Tiny Triumphs of a Giant DisasterValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (99)

- The Heart of Addiction: A New Approach to Understanding and Managing Alcoholism and Other Addictive BehaviorsDa EverandThe Heart of Addiction: A New Approach to Understanding and Managing Alcoholism and Other Addictive BehaviorsNessuna valutazione finora

- Alcoholics Anonymous, Fourth Edition: The official "Big Book" from Alcoholic AnonymousDa EverandAlcoholics Anonymous, Fourth Edition: The official "Big Book" from Alcoholic AnonymousValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (22)

- Allen Carr's Easy Way to Quit Smoking Without Willpower: The best-selling quit smoking method updated for the 21st centuryDa EverandAllen Carr's Easy Way to Quit Smoking Without Willpower: The best-selling quit smoking method updated for the 21st centuryValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (47)

- The Easy Way to Stop Gambling: Take Control of Your LifeDa EverandThe Easy Way to Stop Gambling: Take Control of Your LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (197)

- You Are More Than This Will Ever Be: Methamphetamine: The Dirty DrugDa EverandYou Are More Than This Will Ever Be: Methamphetamine: The Dirty DrugNessuna valutazione finora

- Stop Drinking Now: The original Easyway methodDa EverandStop Drinking Now: The original Easyway methodValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (29)

- Quitting Smoking & Vaping For Dummies: 2nd EditionDa EverandQuitting Smoking & Vaping For Dummies: 2nd EditionNessuna valutazione finora

- Easyway Express: Stop Smoking and Quit E-CigarettesDa EverandEasyway Express: Stop Smoking and Quit E-CigarettesValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (15)

- Psilocybin Mushrooms: A Practical Guide to the Types and Magic Effects of Psychedelic MushroomsDa EverandPsilocybin Mushrooms: A Practical Guide to the Types and Magic Effects of Psychedelic MushroomsValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (14)

- THE FRUIT YOU’LL NEVER SEE: A memoir about overcoming shame.Da EverandTHE FRUIT YOU’LL NEVER SEE: A memoir about overcoming shame.Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (7)

- Healing the Addicted Brain: The Revolutionary, Science-Based Alcoholism and Addiction Recovery ProgramDa EverandHealing the Addicted Brain: The Revolutionary, Science-Based Alcoholism and Addiction Recovery ProgramValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (9)

- Living Sober: Practical methods alcoholics have used for living without drinkingDa EverandLiving Sober: Practical methods alcoholics have used for living without drinkingValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (50)

- Healing the Scars of Addiction: Reclaiming Your Life and Moving into a Healthy FutureDa EverandHealing the Scars of Addiction: Reclaiming Your Life and Moving into a Healthy FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (7)

- Twelve Steps and Twelve Traditions: The “Twelve and Twelve” — Essential Alcoholics Anonymous readingDa EverandTwelve Steps and Twelve Traditions: The “Twelve and Twelve” — Essential Alcoholics Anonymous readingValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (11)

- Alcoholics Anonymous: The Landmark of Recovery and Vital LivingDa EverandAlcoholics Anonymous: The Landmark of Recovery and Vital LivingValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (291)

- The Stop Drinking Expert: Alcohol Lied to Me Updated And Extended EditionDa EverandThe Stop Drinking Expert: Alcohol Lied to Me Updated And Extended EditionValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (63)

- Blood Orange Night: My Journey to the Edge of MadnessDa EverandBlood Orange Night: My Journey to the Edge of MadnessValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (42)