Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Introduction To General Linguistics (Syntax)

Caricato da

ithacaevadingTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Introduction To General Linguistics (Syntax)

Caricato da

ithacaevadingCopyright:

Formati disponibili

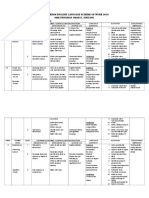

Introduction to General Linguistics WS12/13

Syntax 3

page 1

Course teacher: Sam Featherston

Phrase structure 2

Important things you will learn in this section:

What distinguishes arguments from adjuncts.

Why sentence structure involves a mental lexicon, in which each word has a lexical entry.

The structure scheme by which adjuncts are attached

1. Arguments and adjuncts

We must now distinguish between arguments and adjuncts. In the example sentence John

quickly cooked the fish for his cat, the subject John and the object fish are arguments. The

verb cook requires that there is someone cooking and something being cooked, so these two

arguments are part of the sense of the verb cook. They are more or less essential to its

meaning. Arguments are usually, but not always, DPs.

But there is another class of constituents, called adjuncts, which contrasts with arguments.

Adjuncts add information, but they are not an essential part of the meaning. In our example,

neither quickly nor for his cat is an argument of cook. They simply give us more detail about

the background or circumstances. Adjuncts are often APs or PPs.

(1) Typical adjuncts in connection with verbs

locative: in Tbingen, from Berlin

temporal: yesterday, in two days

manner: in a nice way, quickly, angrily

reason: because of John, due to some problems

(where?)

(when?)

(how?)

(why?)

Here the constituents that are arguments are underlined, and adjuncts are italicized.

(2) a.

b.

c.

d.

e.

[My best friend] ate [a bowl of vegetable soup] [in Brighton] [at four o'clock]

[My brother] sold [his neighbour] [his old radio]

[John] met [our neighbour] [in the park] [on Tuesday]

[Mary] dined [in Salerno] [at four oclock]

[Unser Nachbar] isst [am

Morgen] [oft] [ein weiches Ei]

Our neighbour eats in-the morning often a soft

egg

Our neighbour often eats a soft-boiled egg in the morning.

NOT DEFINITIONS, BUT...

argument [G. Argument] an argument of a verb (or adjective, noun, ..) is a constituent that

is typically a participant in the core meaning of that verb (or adjective, noun..).

adjunct [G. Adjunkt] a constituent adding additional information or detail, typically

circumstances, to another element. The presence of an adjunct is not required.

1.1 Arguments of nouns

Nouns can take arguments too, but these are usually optional.

(3) a. the construction [PP of a house]

b. the destruction [PP of the city]

Introduction to General Linguistics WS12/13

page 2

Such PPs with nouns are classified as arguments because when they are left out, there is a

sense in which they are understood to be present, in the same way as they are with a verb.

Nouns relating to verbs can often have a reading as a process or a reading as a result. So the

process construction (= the constructing) is always the construction of something.

Construction with a process meaning thus works the same way as the verb construct, with

arguments. The result construction (= a building) has no arguments, because this is a result,

not a process.)

Nouns which are related to transitive verbs will often take arguments. Nouns which mean

things which are a part of a relationship often take arguments too.

(4) a.

b.

c.

d.

the student (of literature)

the painter (of this picture)

the daughter (of Dorothea Brooke)

the side (of the house)

(cf to study literature)

(cf paint a picture)

(being a daughter is a relationship)

(a side is a part relative to a whole)

Notice that there are also adjuncts that go with nouns. These also often have the form of a PP.

(5) a. the daughter of Mary Anne Evans [PP from her first marriage]

b. the student of literature [PP in Tbingen]

1.2 Typical features of arguments

Obligatoriness: Arguments are often obligatory: eg devour needs a direct object.

(6) a. The werewolf devoured the rabbit.

b.*The werewolf devoured.

Der Werwolf verschlang das Kaninchen.

*Der Werwolf verschlang.

However this test must be applied with some care: arguments are not always obligatory. For

example, eat may stand with or without an object. The absence of a constituent does not

mean it is an adjunct; it may just be understood. If we say Bella was eating, it is clear that

Bella was eating something, even if we dont say what. We cant eat nothing. So:

(7) Bella was eating nothing

means "Bella wasn't eating". On the other hand, (8) is meaningless.

(8) *Bella was sleeping something

Uniqueness: an argument can be realized by one constituent, but not by two, or by none.

(9) a. [My sister] is sleeping.

b.* [my sister] [my brother] is/are sleeping.

c.* Is sleeping.

On the other hand, there can be many adjuncts with a given verb or noun:

(10) a. Edward slept [in the park] [at noon] [on Tuesday].

b. The destruction of the city [in the 13th century] [after a long battle]

c. an [uninhabited] [big] [white] house [near the beach]

Introduction to General Linguistics WS12/13

page 3

Category: Arguments are often DPs, but not always. We can tell that the PP in (10) is an

argument of the verb put. The verb put requires a place for the direct object to be put.

Arguments may be required to be of a particular category. This is not so of adjuncts.

(11) a. *Mary put the book

b. *Jacob lived

c. *George looked/felt

requires

requires

requires

[PP on the table]

[PP in Bruchsal]

[AP happy, stupid, embarassed]

Word order: In English, an object normally stands next to its verb. If there is an adjunct, it

will follow the argument. We cannot usually put the adjunct between the verb and its object.

This tendency exists across languages, but other factors affect the order too, so it may not be

clear in every language.

(12) a. John read [a book] [in the garden]

V argument adjunct

b.*John read [in the garden] [a book]

V adjunct

argument

(13) a. John saw [Mary] [in the cafeteria] [on Tuesday]

b.*John saw [in the cafeteria] [Mary] [on Tuesday]

c.* John saw [in the cafeteria] [on Tuesday] [Mary]

The same effect can be observed with nouns.

(14) a. a student [of linguistics] [in Tbingen]

b.*a student [in Tbingen] [of linguistics]

(15) a. the daughter [of Mary] [from her first marriage]

b.*the daughter [from her first marriage] [of Mary]

2 Arguments and the mental lexicon

Words and rules: Linguistic structures must obey general rules in a theory of grammar, but

they must also reflect the properties of individual words. For example, we saw earlier that

English nouns can take PP complements but not DP complements, unlike verbs which can

take DP arguments. This is a rule, it applies to all nouns.

However there are also important restrictions that come from individual lexical items (ie

words). The arguments that a lexical item requires are specific to itself.

Arguments in lexical entries: The verb see takes a DP direct object, while the verb look

takes a PP object. These are located in the mental lexicon. For example, the mental lexical

entry of put contains (at least) this information:

(16) Lexical entry of put:

a. grammatical category: V

b. pronunciation: [pt]

c. argument structure: <DP1, DP2, PP3>

When you learn a word, what information do you memorize with it? Part of this information

will be its required or optional arguments.

Introduction to General Linguistics WS12/13

page 4

Arguments are the constituents that occur in the argument structure of the lexical entry.

Adjuncts do not occur in the lexical entry.

(17) I put my mobile phone into my pocket last night to keep it safe.

The constituents [I], [my mobile phone], and [into my pocket] are arguments, since they

represent <DP1, DP2, PP3> in the argument structure of put. On the other hand, [last night]

and [to keep it safe] are adjuncts, and thus do not appear in the argument structure of put.

2.1 The notation of argument structure

Arguments appear in <angled brackets>. Subjects get extra angled brackets: <subjectargument, <object-arguments>>, or <external_argument, <internal_arguments>>

(18) Lexical entry of put:

a. grammatical category: V

b. pronunciation: [pt]

c. argument structure: <DP1, <DP2, PP3>>

Category type: For internal arguments the category is always specified: <..., <DP2, PP3>>.

Technically speaking, we do not need to specify that the subject must be a DP. Subjects are

always DP. It would be more economical to let external rules specify this. Lexical entries

are for word-specific idiosyncratic information, that which is not included in the rules. This

should be as little as possible, since rules are, in terms of mental effort, cheap, and wordspecific information is expensive, that is, requires more effort.

(19) Argument structure of put

<

X1,

< DP2,

PP3 >>

|

external arg.

internal arguments

|

|

tells the grammar that

tells the grammar that these will be

this will be the subject

objects, with categories DP and PP

Here, however, we shall mark subjects as DP, since they are DP.

Round brackets: Optional arguments can be marked with round brackets:

devour: <DP1, <DP2>> with an obligatory object,

eat: <DP1, <(DP2)>> with an optional object.

Introduction to General Linguistics WS12/13

page 5

3 The syntactic representation of arguments

A verb or noun combines with its arguments, creating a phrase (VP, NP, ...). The details in

the lexical entry specify what arguments are necessary.

The argument structure in the lexical entry projects into the syntactic structure.

requirements on all arguments must be satisfied as sisters to the head.

(22)

a. verb with one object

VP

V

|

read

lexical

entry:

V

|

put

a book

ategory: V

arg.-struc.: <X1, <DP2>>

...

N

|

neighbor

lexical

entry

b. verb with two objects

VP

DP2

c. noun with one argument

NP

The

DP2

PP3

a book

on the table

category: V

arg.-struc.: <X1, <DP2, PP3>>

...

d. verb with no object

VP

PP

e. noun with no argument

NP

V

|

sleep

of Mary

category: N

arg.-struc.: < <DP2>>

...

N

|

house

category: V

category: N

arg.-struc.: <X1, < >>

We therefore find the following structures:

(23) a. verb with one object

b. verb with two objects

VP

V

|

read

VP

DP

a book

c. noun with one argument

NP

N

|

neighbour

PP

of Mary

V

|

put

DP

a book

d. verb with no object

VP

V

|

sleep

PP

on the table

e. noun with no argument

NP

N

|

house

Remember: Since arguments are requirements of the head, they must be attached as sisters

to the head X. They are thus daughters of the the phrasal projection of the head XP.

Introduction to General Linguistics WS12/13

page 6

4 The syntactic representation of adjuncts

The difference between arguments and adjuncts in the structure is illustrated here:

(24) a. structure for arguments

b. structure for adjuncts

XP

X

XP

YP

argument

XP

ZP

adjunct

Arguments are sisters to X, a word, and daughters to XP, the mother of X. Since adjuncts

are optional, there is no fixed position for them. Adjuncts are sisters to XP and daughter to a

higher XP. We have to generate this additional phrasal projection above the existing

phrasal projection XP.

(26)

a. adjunct to an NP with an argument

NP new!

NP

N

|

king

b. adjunct to an NP with no argument

NP new!

PP

NP

|

N

|

tourist

PP

from Gascony

(adjunct)

of France

c. adjunct to a VP with one argument

VP new!

VP

V

|

read

with a camera

(adjunct)

d. adjunct to a VP with no argument

VP new!

PP

DP

PP

VP

|

V

|

sleep

in the garden

(adjunct)

a book

PP

during the show

(adjunct)

This difference between arguments and adjuncts makes sense in terms of the lexical entry:

the specification from the lexical entry of a word X drives the addition of sisters to the word

level category X. Adjuncts are not projected by the argument structure, they are added on

the outside, so to speak, on a new outer layer.

(27)

a. structure for arguments

XP

X

lexical

entry:

YP

argument

category: X

arg.struc.: YP

b. structure for adjuncts

XP

XP

YP

adjunct

Introduction to General Linguistics WS12/13

page 7

This explains why several adjuncts can be stacked. The addition of each adjunct causes the

addition of a new highest phrasal node. We can do this again and again (and again.....).

(28)

a.

b.

c.

VP

VP

VP

|

V

|

slept

VP

|

V

|

slept

VP

PP

VP

|

V

|

slept

in the park

PP

PP

at noon

in the park

This structural difference between arguments and adjuncts explains the difference in wordorder that we saw above. We can build a structure of a verb plus complement plus adjunct:

(29)

VP

VP

V

|

read

PP

DP

in the garden

(adjunct)

a book

The argument DP is sister to the V and daughter of VP. The adjunct PP is sister to VP and

daughter of VP . Fine.

If we add the adjunct first, it becomes sister of VP, daughter of a new VP. If we want to add

an argument after this, there is no attachment position which is both after the adjunct and still

sister to V. The argument can therefore not be attached outside the adjunct.

(30)

a. you can add an adjunct

b. but you cant add an argument outside

VP

VP

VP

|

V

|

read

VP

PP

in the garden

(adjunct)

VP

|

V

|

read

DP

PP

in the garden

(adjunct)

a book

Introduction to General Linguistics WS12/13

page 8

Exercises syntax 3 Arguments and adjuncts.

1a. How many arguments do the following verbs have?

yawn, write, send, lend, kill, grow, kick, hop, bet, marry (two possibilities), die, rain, show,

introduce (people)

1b. And these nouns?

boss, garden, growth, neighbour, loan, tree, uncle, front, phone, kick, cover

2. Identify the arguments and adjuncts in these examples. Draw trees.

a. cook some pasta

arrive at my home

run quickly

sing in the choir

listen to the music

fax a report to the ministry

b. the husband of my friend

the government of the country

the politician from the capital

a picture of an apple

c. ride a bicycle in the country

buy an ice cream for a child

see the detective with a telescope

drive a car carelessly

wander in the afternoon along the Neckar

the author of this book

3. Distinguish adjuncts and arguments and draw trees for the following:

see the sea

the brother of the prince

(to) eat some chips with your fingers

sleep on the sofa

prepare the lunch in the kitchen

write carefully on the card

watch the television

the queen of the Netherlands on her throne

listen to the radio in the morning.

describe my theory with some examples

leave the town for a while

a letter from my brother

a statue of the bishop of this province

a photo of my cousin from the south

4. das Meer sehen

the sea see

mit diesen Essstbchen den Reis essen

with these chopsticks the rice eat

die abbltternde Bemalung der

Mauer

the peeling.off painting of.the wall

klar sehen

clearly see

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Sentence Structure 17052023 102228amDocumento22 pagineSentence Structure 17052023 102228amtahseen ullahNessuna valutazione finora

- 12 Mono Vs Bi TVs 2015Documento5 pagine12 Mono Vs Bi TVs 2015Laydy HanccoNessuna valutazione finora

- Subject, Finite and Infinite Verb. Advance Grammar and StructureDocumento14 pagineSubject, Finite and Infinite Verb. Advance Grammar and StructureYeppy AsIINessuna valutazione finora

- Sentence and List StructureDocumento8 pagineSentence and List StructureThomy ParraNessuna valutazione finora

- Comparative Case Structure Study of English, German Annd Marathi Languages With Respect To MorphologyDocumento11 pagineComparative Case Structure Study of English, German Annd Marathi Languages With Respect To MorphologySwamineeNessuna valutazione finora

- Glosario: and Reflexives?Documento5 pagineGlosario: and Reflexives?EvaNessuna valutazione finora

- SU 9.2. Dangling Participles ST HODocumento5 pagineSU 9.2. Dangling Participles ST HODumitrița PopaNessuna valutazione finora

- Verbs - Classification and Internal ArgumentsDocumento6 pagineVerbs - Classification and Internal ArgumentsMagalí StylesNessuna valutazione finora

- Morphology: The Analysis of Word Structure: Near) Encode Spatial RelationsDocumento6 pagineMorphology: The Analysis of Word Structure: Near) Encode Spatial RelationsYašmeeñę ŁębdNessuna valutazione finora

- An Introduction To Latin With Just In Time GrammarDa EverandAn Introduction To Latin With Just In Time GrammarValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (4)

- A Short New Testament Syntax: Handbook with ExercisesDa EverandA Short New Testament Syntax: Handbook with ExercisesNessuna valutazione finora

- Artikel JEE NizamDocumento12 pagineArtikel JEE NizamNizam SadiqNessuna valutazione finora

- 2020 Sentence Elements TheoryDocumento10 pagine2020 Sentence Elements TheoryCele AlagastinoNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 1 - English - WWW - Rgpvnotes.inDocumento17 pagineUnit 1 - English - WWW - Rgpvnotes.inabc asassNessuna valutazione finora

- The Structure of English: The Verb PhraseDocumento209 pagineThe Structure of English: The Verb PhraseAttila NagyNessuna valutazione finora

- Artikel JEE NizamDocumento13 pagineArtikel JEE NizamNizam SadiqNessuna valutazione finora

- Presentations 2aDocumento5 paginePresentations 2aalu0101349176Nessuna valutazione finora

- ErlanggaDocumento11 pagineErlanggaVelysa Ayu apriliaNessuna valutazione finora

- Form of The PassiveDocumento4 pagineForm of The PassiveAndra AndeeNessuna valutazione finora

- Morphology and SyntaxDocumento13 pagineMorphology and Syntaxshelda audita100% (1)

- Merged DocumentDocumento28 pagineMerged DocumentJamirah Maha ShahinurNessuna valutazione finora

- The Subject 1. Distinctive Syntactic Properties of The Subject in EnglishDocumento4 pagineThe Subject 1. Distinctive Syntactic Properties of The Subject in Englishsonia wilia100% (1)

- NOTES ON LANGUAGE STRUCTURES - CompressedDocumento20 pagineNOTES ON LANGUAGE STRUCTURES - CompressedGloriaNessuna valutazione finora

- Foundations of Syntax Lecture Slides 4Documento22 pagineFoundations of Syntax Lecture Slides 47doboz1csardabanNessuna valutazione finora

- 2 Group Relative ClausesDocumento10 pagine2 Group Relative ClausesAssia Atumane AmadeNessuna valutazione finora

- Power Point Presentation 4 SyntaxDocumento35 paginePower Point Presentation 4 SyntaxNasratullah AmanzaiNessuna valutazione finora

- English 4 NotesDocumento7 pagineEnglish 4 NotesFarooq Ali KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Understanding the Concepts of English PrepositionsDa EverandUnderstanding the Concepts of English PrepositionsValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- Isang Dosenang Klase NG High School Students: Jessalyn C. SarinoDocumento8 pagineIsang Dosenang Klase NG High School Students: Jessalyn C. SarinoMary Jane Reambonanza TerioteNessuna valutazione finora

- Inglese 1Documento32 pagineInglese 1Daria PiliNessuna valutazione finora

- MorfosinDocumento16 pagineMorfosinMaría GarcíaNessuna valutazione finora

- Conspecte Lec - Anul 3 Sem 2Documento15 pagineConspecte Lec - Anul 3 Sem 2Andra PicusNessuna valutazione finora

- 1-Investigate and Write What's Grammar. Give Details.: Classification of VerbsDocumento7 pagine1-Investigate and Write What's Grammar. Give Details.: Classification of VerbsEnrique RosarioNessuna valutazione finora

- Copulative PredicationsDocumento10 pagineCopulative PredicationsGeorgescu Simona MariaNessuna valutazione finora

- Complementation in SyntaxDocumento16 pagineComplementation in SyntaxTrust Emma100% (1)

- Tema 23Documento7 pagineTema 23Jose S HerediaNessuna valutazione finora

- Intro To LinguisticsDocumento10 pagineIntro To LinguisticsMark Andrew FernandezNessuna valutazione finora

- TOIEC Grammar - Relative ClausesDocumento6 pagineTOIEC Grammar - Relative Clausessilly witch100% (1)

- Makalah Relative Pronoun Kel 3Documento8 pagineMakalah Relative Pronoun Kel 3Muhamad Nurhadiyansyah100% (1)

- Dependent ClauseDocumento10 pagineDependent ClauseawqomarullahNessuna valutazione finora

- Performdigi: The Sentence in English GrammarDocumento5 paginePerformdigi: The Sentence in English Grammarmuhammad arshidNessuna valutazione finora

- Syntax-Group Work-Updated-1Documento18 pagineSyntax-Group Work-Updated-1malonamige20Nessuna valutazione finora

- English Semantics: Sentence Meaning and Propositional ContentDocumento59 pagineEnglish Semantics: Sentence Meaning and Propositional ContentXoan PhạmNessuna valutazione finora

- Adjunct Conjuncts Disjuncts Ejecutivo IIDocumento5 pagineAdjunct Conjuncts Disjuncts Ejecutivo IIErica RajoyNessuna valutazione finora

- Clefting ResearchDocumento5 pagineClefting ResearchBlack IQNessuna valutazione finora

- Week 7 Semantics of Phrase and Sentence - Lecture Notes2022 2023Documento3 pagineWeek 7 Semantics of Phrase and Sentence - Lecture Notes2022 2023Maria TeodorescuNessuna valutazione finora

- Paper 4103 4111 Du Confirmed PDFDocumento10 paginePaper 4103 4111 Du Confirmed PDFElla CelineNessuna valutazione finora

- 5CQBT - Nguyen Thi Ai Thu - Basic Sentence Patterns in English and VietnameseDocumento15 pagine5CQBT - Nguyen Thi Ai Thu - Basic Sentence Patterns in English and Vietnamesenguyenthikieuvan100% (1)

- SyntaxDocumento19 pagineSyntaxTaniușa SavaNessuna valutazione finora

- Noun PhraseDocumento4 pagineNoun PhraseHarakhty KeahiNessuna valutazione finora

- SubordinationDocumento26 pagineSubordinationKomang AryaNessuna valutazione finora

- Syntax Final ProjectDocumento24 pagineSyntax Final ProjectRachditya Puspa AndiningtyasNessuna valutazione finora

- Svoca NotesDocumento4 pagineSvoca NotessonulalaNessuna valutazione finora

- A Very Brief Guide To English Grammar And PunctuationDa EverandA Very Brief Guide To English Grammar And PunctuationValutazione: 2 su 5 stelle2/5 (6)

- 3 2 PDFDocumento19 pagine3 2 PDFYuliia HrechkoNessuna valutazione finora

- The Verb PhraseDocumento31 pagineThe Verb PhraseJerwin AdayaNessuna valutazione finora

- General Number and The Semantics and Pragmatics of Indefinite Bare Nouns in Mandarin Chinese Author Hotze Rullmann and Aili YouDocumento30 pagineGeneral Number and The Semantics and Pragmatics of Indefinite Bare Nouns in Mandarin Chinese Author Hotze Rullmann and Aili YouMaite SosaNessuna valutazione finora

- Word OrderDocumento20 pagineWord OrderKardji AgusNessuna valutazione finora

- Coursework LADocumento10 pagineCoursework LANguyễn TrangNessuna valutazione finora

- Grammatical and Lexical Factors in Sound ChangeDocumento28 pagineGrammatical and Lexical Factors in Sound ChangeithacaevadingNessuna valutazione finora

- What I Needed To Know To Get Published Teaching Frightened Graduate Students To Write For PublicationDocumento26 pagineWhat I Needed To Know To Get Published Teaching Frightened Graduate Students To Write For PublicationRadu CucuteanuNessuna valutazione finora

- Aronoff & Schvaneveldt (Productivity)Documento9 pagineAronoff & Schvaneveldt (Productivity)ithacaevadingNessuna valutazione finora

- Rela 2014 0014 LibreDocumento21 pagineRela 2014 0014 LibreithacaevadingNessuna valutazione finora

- This Is My FamilyDocumento2 pagineThis Is My Familyali bettaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Ingles 2 PaolaDocumento3 pagineIngles 2 Paolayeimi castañedaNessuna valutazione finora

- Grammar Tests-21 PDFDocumento1 paginaGrammar Tests-21 PDFCostas NovusNessuna valutazione finora

- Grammatik Im Kontext Week 7Documento11 pagineGrammatik Im Kontext Week 7Moni Fetke0% (1)

- General Principles of Sentence: Rustania Farmawati S.PD., M.PDDocumento6 pagineGeneral Principles of Sentence: Rustania Farmawati S.PD., M.PDHavia RaiffazaNessuna valutazione finora

- NPNC 1Documento17 pagineNPNC 1Nguyen LoanNessuna valutazione finora

- Review Basic English GrammarDocumento2 pagineReview Basic English GrammarSun WooNessuna valutazione finora

- English Presentation Salman Khan 3rd SEMESTER 7C'sDocumento23 pagineEnglish Presentation Salman Khan 3rd SEMESTER 7C'sSalman Rahi100% (1)

- Verbos Irregulares - LewolangDocumento4 pagineVerbos Irregulares - LewolangAndrea Marlene Fretes BalbuenaNessuna valutazione finora

- Infinitive: 1.1 After Certain Verbs: A. Verbs Followed by TO+ InfinitiveDocumento6 pagineInfinitive: 1.1 After Certain Verbs: A. Verbs Followed by TO+ InfinitiveAntonia FerriolNessuna valutazione finora

- Watching TV Listening To Music Reading BooksDocumento20 pagineWatching TV Listening To Music Reading BooksScentCandleNessuna valutazione finora

- Word Formation in AdvertisingDocumento12 pagineWord Formation in AdvertisingSimona SpasovaNessuna valutazione finora

- Universitas Bina Bangsa: Lembar Jawaban Semester Genap TAHUN AKADEMIK 2021-2022Documento2 pagineUniversitas Bina Bangsa: Lembar Jawaban Semester Genap TAHUN AKADEMIK 2021-2022Setia OptikNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 1 Short Test 1A: GrammarDocumento1 paginaUnit 1 Short Test 1A: GrammarleonormmapNessuna valutazione finora

- Learn 40 Common Regular Verbs in EnglishDocumento1 paginaLearn 40 Common Regular Verbs in EnglishCatherine RamosNessuna valutazione finora

- Grammar Practice High Five - 5 - 6Documento134 pagineGrammar Practice High Five - 5 - 6Marta NortonNessuna valutazione finora

- Syllabus Cu Engl 101Documento6 pagineSyllabus Cu Engl 101api-417692500Nessuna valutazione finora

- Communication English-I (40011)Documento9 pagineCommunication English-I (40011)SohraldNessuna valutazione finora

- 28 Getting Started in Ladakhi A PhrasebookDocumento143 pagine28 Getting Started in Ladakhi A PhrasebookHoai Thanh Vu100% (8)

- English Form 5 RPT 2016Documento8 pagineEnglish Form 5 RPT 2016Mimi NRNessuna valutazione finora

- Translation of English Complex SentencesDocumento30 pagineTranslation of English Complex SentencesGoranM.MuhammadNessuna valutazione finora

- A Test On The Simple PastDocumento5 pagineA Test On The Simple PastCarla NascimentoNessuna valutazione finora

- What Is A Phrasal VerbDocumento5 pagineWhat Is A Phrasal VerbFolake AdedejiNessuna valutazione finora

- Phrasal Verbs SetDocumento1 paginaPhrasal Verbs SetEduard LisogorNessuna valutazione finora

- Sentence Construction: Simple Compound ComplexDocumento6 pagineSentence Construction: Simple Compound Complexsal811110Nessuna valutazione finora

- Verb AgreementDocumento25 pagineVerb AgreementTariza SuciNessuna valutazione finora

- 01.2.19 Fragments - Mowsoof Sifah Part I-IVDocumento4 pagine01.2.19 Fragments - Mowsoof Sifah Part I-IVsaniNessuna valutazione finora

- The English Verb SystemDocumento51 pagineThe English Verb SystemSalomao RodriguesNessuna valutazione finora

- Grammar-EXTRA NI 3 Unit 1 Present-Simple Present-Continuous And-Adverbial-Phrases-Of-Frequency1 PDFDocumento1 paginaGrammar-EXTRA NI 3 Unit 1 Present-Simple Present-Continuous And-Adverbial-Phrases-Of-Frequency1 PDFfergo1Nessuna valutazione finora

- 2324 Level J (GR 7 UAE - GR 8 Gulf) English Exam Related Materials T1 Wk5Documento2 pagine2324 Level J (GR 7 UAE - GR 8 Gulf) English Exam Related Materials T1 Wk5moza1 jumaNessuna valutazione finora