Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

1997 Haynal On Ferenc As Psychoanalist

Caricato da

Ana InésTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

1997 Haynal On Ferenc As Psychoanalist

Caricato da

Ana InésCopyright:

Formati disponibili

This article was downloaded by: [University of Western Ontario]

On: 06 June 2015, At: 14:53

Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954

Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T

3JH, UK

Psychoanalytic Inquiry: A

Topical Journal for Mental

Health Professionals

Publication details, including instructions for

authors and subscription information:

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/hpsi20

For a metapsychology of

the psychoanalyst: Sndor

Ferenczi's quest

Andr Haynal M.D.

a

a b c

Professor of Psychiatry , University of Geneva

Training and Supervising Analyst and Former

President of the Swiss Psychoanalytical Society

c

20 B, Gradelle, Geneva, CH1224, Switzerland

Published online: 20 Oct 2009.

To cite this article: Andr Haynal M.D. (1997) For a metapsychology of the

psychoanalyst: Sndor Ferenczi's quest, Psychoanalytic Inquiry: A Topical Journal for

Mental Health Professionals, 17:4, 437-458, DOI: 10.1080/07351699709534141

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07351699709534141

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the

information (the Content) contained in the publications on our platform.

However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no

representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness,

or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views

expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and

are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the

Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified

with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable

for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses,

damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising

directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the

use of the Content.

Downloaded by [University of Western Ontario] at 14:53 06 June 2015

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study

purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution,

reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form

to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms & Conditions of access and use can

be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

Downloaded by [University of Western Ontario] at 14:53 06 June 2015

For a Metapsychology of the

Psychoanalyst: Sndor Ferenczi's Quest

A N D R E H A Y N A L , M.D.

YOUNG CHILD is FAMILIAR with much knowledge . . . that later

becomes buried by the forces of repression" (Ferenczi, 1923

[257], p. 350).1 Small children are often amusing because they put into

wordssometimes a bit awkwardlywhat they (still) perceive without repressing; adults for whom the same material has already been

repressed then receive their words as a kind of revelation. The effect

can either be the amusement of liberationa sort of "aha!" experienceor, because of their own repression, one that creates tension

and even hostility: "How stupid!" or "One doesn't say things like

that!" which corresponds to an intention to reinforce the adult's

repression and at the same time to inculcate in the child the "do-notsay," indeed the "do-not-think."

"Wise baby"he himself used the English term in the German text

(Ferenczi, 1923 [257] and Ferenczi, 1932 [308], p. 274)is what

Ferenczi was to remain all his life. In that, he differed from his fellow

pioneers and even from his master, Freud. His perceptiveness

"THE

Dr. Haynal is Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Geneva; Training and Supervising

Analyst and Former President of the Swiss Psychoanalytical Society.

Translated from the French by Linda Butler, Washington, DC.

1

Ferenczi's writings are quoted, as customary, by reference to the year of their original

publication; the number in square brackets identifies the work in Balint's numerical list of

Ferenczi's writings (S. Ferenczi, Bausteine zur Psychoanalyse, Vols. I-IV. Bern: Huber, 1964).

437

Downloaded by [University of Western Ontario] at 14:53 06 June 2015

438

ANDRE HAYNAL

preceded his encounter with psychoanalysis, so it is not surprising that

the problems that would be central to the work of Ferenczi the psychoanalyst had already emerged in Ferenczi the pre-psychoanalytic.

In saying that children are "wise," that the infant is wise, Ferenczi

thus introduced the idea that the child's perception, ideation, and

expression of feeling and sensation are not yet distorted by the

defenses, insincerity, and inauthenticity that will later be imposed

upon them. In this core, we already find the notion not of a certain

"childish innocence"as has recently been incorrectly understood; it

is not a question of innocence in the "asexual" sense, but rather of an

infantile authenticity, to use today's vocabulary. That indeed was the

program of Ferenczi the analystto attain sincerity and authenticity,

not only in the analysand, but first and foremost in the analyst; as he

would later write to Freud, one should be able to "tell the truth to

everyoneto one's father, one's professor, one's neighbour and even

to the king" (109 Fer., 5.2.19102). Similarly, he aimed at bringing out

the child in the adult, in the human being, for it is that part which

represents the individual's greatest value. And if he noted that "the

idea of the 'wise baby'" could be discovered only by a "wise baby"

(Ferenczi, 1932 [308], p. 274), he thus presented himself as one, as

someone close to the child, to the child's desires, and to sufferings

imposed by others.

It is interesting in this context to evoke the epistolary discussion

that took place between Ferenczi and Freud as early as 1911, when

they hardly knew each other, in which Ferenczi wrote that, since very

small children do not repress, they do not need the symbolic to represent the repressed (228 Fer., 7.6.1911): "no need of indirect language"

(226 Fer., 3.6.1911). In this exchange of ideas, we see already

Ferenczi the proponent of the authenticity of the child. We also see the

kernel of an idea he would elaborate in what was to be his swan song,

"Confusion of Tongues Between Adults and the Child" (Ferenczi,

1933 [294]); for Ferenczi, it is for this reason that children and adults

do not understand and even "misunderstand" each other.

Ferenczi's letters to Freud are designed "Fer." and those from Freud to Ferenczi by "Fr." The

letters are numbered according to the nomenclature of the Freud-Ferenczi Correspondence, of

which the first and second volumes were published by Harvard University Press (see Freud and

Ferenczi, 1991, 1996).

Downloaded by [University of Western Ontario] at 14:53 06 June 2015

A METAPSYCHOLOGY OF THE ANALYST

439

In the pre-Freudian Ferenczi, we encounter the principal themes

that were likewise to preoccupy him as an analyst.

1. The first of these is communication in its most occult forms, in

the true sense of the term (Ferenczi, 1899). The profound relationships

in hypnosis (Ferenczi, 1904a), as well as the study of communication

in love (Ferenczi, 1901), very early took their place in this line of

inquiry; later was added his preoccupation with the problem of

change, notably in psychoanalysis.3

When he was still an intern at the St. Rokus Hospital, one of the

oldest in Budapest, already he showed his bent for matters of the

psyche. Working under a very authoritarian and even spiteful supervisor ("a hard man," Ferenczi, 1917 [199], p. 288) who made him attend

to prostitutes instead of letting him devote his energies to the study of

psychological phenomena within the framework of the neuropsychiatry of the day, he experimented through exploring himself ("lacking

another material for observation, I carried out psychological experiments on myself" [Ferenczi, 1917 [199], p. 288] using the "free association" method of the time as well as the "autonomic writing" "much

talked about by spiritists" (Ferenczi, 1917 [199], p. 288).4

Thus, a kind of self-analysis was already unfolding, in solitude, in

unhappy conditions. It was during this period that he conceived his

article on spiritism (Ferenczi, 1899), an astounding article where

already there is a question of the functioning of the unconscious:

"What we know today proves beyond any possible doubt that in the

3

He would write: "It is this confidence that establishes the contrast between the present and

the unbearable traumatogenic past, the contrast which is absolutely necessary for the patient in

order to enable him to re-experience the past no longer as hallucinatory reproduction but as an

objective memory" (Ferenczi, 1933 [294], p. 160). ("Dieses Vertrauen ist jenes gewisse Etwas,

das den Kontrast zwischen der Gegenwart und der unleidlichen, traumatogenen Vergangenheit

statuiert, den Kontrast also, der unerlasslich ist, damit man dir Vergangenheit nicht mehr als

halluzinatorische Reproduktion, sondern als objektive Erinnerung aufleben lassen kann")

(Ferenczi, Bausteine zur Psychoanalyse, 1964, Band III, S. 516).

4

"I believed that the late hour, fatigue and a little emotion favored the 'psychic splitting." I

would thus take a pencil and, holding it lightly, would place the point on a sheet of white paper;

I was determined to abandon completely the instrument to itself, to let it write what it pleased.

First came meaningless scribblings, then letters and a few words (which I had not thought of),

and finally coherent sentences. I soon reached the point of carrying out veritable dialogues with

my pencil: I would ask it questions and received totally unexpected responses. With the eagerness of youth I first questioned it about the grand theoretical problems of life, then moved on to

practical questions. The pencil then made the following proposal: 'Write an article on spiritism

for the review Gyogyaszat, the editor would be interested' - (Ferenczi, 1917 [199], p. 288).

Downloaded by [University of Western Ontario] at 14:53 06 June 2015

440

ANDRE HAYNAL

psychic functioning there exists many unconscious (ontudatlan) and

semi conscious elements" (translated from the Hungarian). Furthermore, he wrote, "there are cleavages in psychic life". He was already

thinking that it is probable that most phenomena of spiritism are based

on the splitting of the psychic functions into two or more parts, only

one of which is placed in the foyer of the convex mirror of the

conscious mind, while the others function outside the conscious level

ipntudat nelkiit) in an autonomous fashion. It is this that explains how

the medium can carry out [her experiments] outside the conscious

level and unintentionally (translated from the Hungarian) (Ferenczi,

1899, p. 478).

Ferenczi's conviction that occult phenomena would shed light on

aspects of tranference, that the Gedankeniibertragung (the transfer of

thought) would make it possible to understand the Ubertragung

(transference per se) and would persist throughout his evolution; it

was a conviction that was also shared by Freud. Furthermore, his

experiments in hypnosis, and notably the deep "connection" ("rapport") it entailed, suggested to him metaphors utilized to study regressive states in transference, states that made possible "the re-living of

the events of the trauma in the analysis" (Ferenczi, 1934 [296],

p. 242). This idea will reappear in his Journal as well (Ferenczi, 1985).

2. A second theme, which appeared some years before his

encounter with Freud, was sexuality, sometimes in its most unusual

forms, as in the case of Roza K (Ferenczi, 1902).

In his article "Love and Science" (Ferenczi 1901), which preceded

by 4 years the "Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality" (Freud,

1905b), he asked himself how the szerelem, or "sexual love" (which

Hungarian is able to render, through a distinctive linguistic feature, in

a single word, in contrast to szeretet, which means simply "love,"

especially in its affective aspect), "frees up immense psychic energy

whose destructive and constructive activity shows the individual and

the species at the height of his capacity to act" (Ferenczi, 1901, p.

190). He emphasizes "the disadvantageous influence of prejudice for

free examination" and quotes Mobiusthe franc-tireur (he uses the

French word in his text) of psychiatry of the timeas saying that this

chapter of science is still to be written. This being the case, Ferenczi

declares that "the only sources for the psychology of love, even today,

are poetry and the literature of novels" (Ferenczi 1901, p. 191), and

Downloaded by [University of Western Ontario] at 14:53 06 June 2015

A METAPSYCHOLOGY OF THE ANALYST

441

that one can learn more from Maupassant and Heine than from

weighty tomes of psychology. He also makes links between love,

possessiveness, the masochistic love of the "misunderstood" person,

jealousy, and these states of lovetoday we would call them regressive statesthat can "threaten the individual with psychosis, licentiousness, criminality or drunkenness" (Ferenczi, 1901, p. 192). As

can be seen, Ferenczi the pre-psychoanalytic is in truth already

psychoanalytic without knowing it.

The biography of Roza K, "a veritable odyssey," is based among

other things on the autobiography of an individual who today would

be categorized as a lesbian, a transvestite, or perhaps even a transsexual. This article, as well as his activity in defense of homosexuals, has

been cited to show Ferenczi's sensitivity to the need to struggle

against repression and to the importance he attached to the role of the

doctor, particularly the psychiatrist, in this struggle. What is striking

about the case study itself is the author's capacity for subtle identification with this unfortunate woman and his willingness, even at the

risk of raising speculations, to give her a certain intelligibility.

3. The third theme in the early Ferenczi that would remain with him

throughout his life was the idea of associationism, the unconscious

connections between different elements of our imagination, thought,

and representations. This idea, already present in his experiments with

"automatic writing," would lead him to Jung, who in 1906 had

published his book on word associations (Jung, 1906a). Ferenczi, with

that capacity for enthusiasm for everything that struck him as likely to

uncover the mysteries of the human soul, immediately seized upon the

method of experimental study of word associations, bought a

chronometer and carried out his "experiments" everywhere, including

in the literary cafes he used to frequent (such as the Cafe Royal of the

grand boulevards of Budapest, near the old National Theater, since

destroyed by the Stalinist bulldozers).

It might be noted that it was that same year of 1906, on 27 May,

that Jung defended Freud's work on Dora (Freud, 1905c) against a

virulent attack by Aschaffenburg at the Congress of Neurologists and

Psychiatrists of South West Germany in Baden-Baden; it was at that

moment that Jung brought his research together with the ideas of

psychoanalysis (Jung, 1906b). He sent a copy of this publication on

this subject to Freud, and Freud's letter of thanks constituted the first

Downloaded by [University of Western Ontario] at 14:53 06 June 2015

442

ANDRE HAYNAL

missive of a long correspondence, encompassing more than 350

letters, that was to continue without interruption until 1914.

Ferenczi, meanwhile, sought a personal contact with Jung at the

beginning of 1907. Jung, after a visit at the beginning of March 1907

to Vienna (where he met Freud on 3 March and participated in a

meeting of the Wednesday Society on the 6th), stopped by Budapest

where he spent a few days with Dr. Fiilop Stein, a friend and colleague

of Ferenczi. It was on this occasion that Ferenczi was able to meet

Jung personally. Later, Ferenczi, pursuing his interest in tests of word

association, travelled to the Burgholzli, the Psychiatric Clinic of

Zurich, to see Jung. We might note here parenthetically that the

importance of the Burgholzli has been much underestimated in the

historiography of psychoanalysis; we should not forget that this was

the first institution that accepted psychoanalysis as such and made

available to it, as material for observation, a larger clientele than that

of the private practitioners, notably of the world of psychoses. Let us

recall, too, the more or less long associations with the clinic of Karl

Abraham, Ludwig Binswanger, Abraham Arden Brill, Imre Decsi,

Max Eitingon, Sandor Ferenczi, Johann Jakob Honnegger, Smith Ely

Jelliffe, Ernest Jones, Alphonse Maeder, Hermann Nunberg, Franz

Riklin, Hermann Rorschach, Eugenie Sokolnicka, Sabina Spielrein,

and Fiilop Stein. In 1908, it was thanks to an introduction by Jung that

Ferenczi, still in the company of Dr. Fiilop Stein, met Freud.

4. The fourth grand theme of Ferenczi's scientific preoccupations

was the child.5 This was the topic on which he would speak when

Freud invited him, the summer of the same year they met, to present a

paper at the Psychoanalytic Congress of Salzburg. There, he evoked

new perspectives on education for children inspired by Freudian

works (Ferenczi, 1908 [63]). He pursued this same line, among others,

in his work on little Arpad (Ferenczi, 1913c [114]), a clinical essay

that showed Ferenczi the analyst at work in a multistage endeavor in

the best tradition of a clinical Sherlock Holmes: to discover the underpinnings of symbolism in the "little Chanticleer" (Ferenczi, 1913c

[114]). In his "Stages in the Development of the Sense of Reality" of

the same year (Ferenczi, 1913b [111]), he developed the idea of the

omnipotence of the child at the beginning of his evolution and, in

5

Back in 1904, he had already taken an interest in the scientific literature concerning "the

development and the functioning of the infantile psyche" (Ferenczi, 1904b).

Downloaded by [University of Western Ontario] at 14:53 06 June 2015

A METAPSYCHOLOGY OF THE ANALYST

443

greater detail, the play of introjection and projection: the work of

Melanie Klein was without doubt powerfully influenced by Ferenczi's

ideas.

Klein later wrote that she had a debt of gratitude toward Ferenczi

and that he had "a streak of genius" (Grosskurth, 1986, p. 73). Indeed,

it was Ferenczi who encouraged her to go into the psychoanalysis of

children. Moreover, his position when Melanie Klein and Anna Freud

were separated by differences of opinion and tensions was misrepresented in widely circulated accounts. Ferenczi was close to the Freud

family and had invited Anna to Budapest on a number of occasions

(for instance, in 1914 [458 Fer., 18.2.1914], 1917, and 1918 [YoungBruehl, 1988, p. 79). It even seems that Freud wanted Ferenczi to

marry his other daughter, Mathilda. The relationship with Melanie

Klein, on the other hand, became difficult in keeping with the developing tensions between Ferenczi and Jones during the 1920s.

Nonetheless, Ferenczi remained "equidistant" between the two during

their quarrel.6 Michael Balint, his spiritual heir, was later to maintain

the same position in London.

Although Ferenczi was never actually a child psychoanalyst and his

predominant professional activity was always the analysis of adults,7

the Wise Baby in him would always remain very close to the child

within the adult, as can be seen in his last writings: "The Adaptation

of the Family to the Child" (1928a [281]), "The Unwelcome Child and

His Death Instinct" (1929 [287]), "Child Analysis in the Analysis of

Adults" (1931 [292]), and in particular his last (completed) published

work: "Confusion of Tongues Between Adults and the Child" (1933

[294]). This paper, presented at the Congress of Wiesbaden in

September 1932, was his spiritual testament. It was also the subject of

some reservations on the part of his colleagues and even of Freud who

wondered whether Ferenczi should or could present these innovative

ideas at this time, or was it premature? With his concept of the analysis of the child in the adult, a new door undoubtedly opens, as was the

case with his prior work, which treats the conflictuality between

adults and children in a new light (Ferenczi, 1931 [292]).

6

He wanted both to expose his experiences and the ideas that came out of them and

recognized in the same breath the merits of Melanie Klein and Anna Freud, whose "systematic

works . . . are universally known and esteemed" (Ferenczi, 1931 [292], p. 128).

7

"I for my part have had very little to do with children analytically" (Ferenczi, 1931 [292],

p. 128).

Downloaded by [University of Western Ontario] at 14:53 06 June 2015

444

ANDRE HAYNAL

Ferenczi entered the psychoanalytic scene in 1909 with his first grand

original work (Ferenczi, 1909 [67]): one senses that in the current of

great traditions established by Freud, a new voice and a new sensibility had seen the day. The "transference" of Ferenczi, without any

doubt, differs from the "transference" in the writings of Freud. It was

clear that this man, then 36 years old, would introduce new and original views, especially in his work of the late 1920s, which would make

of him "the father of modern psychoanalysis" (Green, 1990, p. 61).

It is fascinating to see how the themes that emerged so early in the

work of Sandor Ferenczi were pursued throughout his entire life,

across his entire creative activity. Just as, in our fantasy life, our

elaboration always turns around the same basic ideas, so it is that the

scientific work of Ferenczi, so spontaneous and so inventive, seems

but the elaboration of a handful of fundamental themes, an elaboration

drawn across various internal and external obstacles to the very end.

In the work of 1909, above and beyond the projective sides of the

transference on the blank screen of the psychoanalyst's person,

already established by Freud, Ferenczi stressed the desire of introjection, which he conceived as a kind of addiction: the subject, particularly the "neurotic," is driven by a constant desire to receive, to enrich

his inner self, to take "into the ego as large as possible a part of the

outer world, making it the object of unconcious fantasies" (Ferenczi,

1909 [67], p. 47). Here, in embryonic form, we find the idea of the

formation of an internal object by introjection and, in his highlighting

of the complementary aspects of introjection and transference, we find

the kernel of the later "projective identification" dear to his student,

Melanie Klein (Klein, 1946). In the constitution of the transference, he

apprehends displacement in the line of the continuity and contiguity of

the associations, for example the role of minor physical resemblances,

despite the "fact that a transference on the ground of such petty analogies strikes us as ridiculous" (Klein, 1946, p. 42). He thus makes a link

with the work of dreams or with jokes examined several years earlier

by Freud (Freud, 1905a), emphasizing as well that these introjections

are for the most part unconscious.

We already glimpse in this article one of the future characteristics

of Ferenczi the mature analyst: he is far from rejecting what he

Downloaded by [University of Western Ontario] at 14:53 06 June 2015

A METAPSYCHOLOGY OF THE ANALYST

445

learned in the profound relationship in hypnosis. But he links these

effects to a revival of late parental influences, recovering in the

profound connection between the hypnotist and the hypnotizedlike

the connection between analyst and analysand in profound psychoanalytic sessionsthe relationship between the loving mother and the

father representing authority, the "remains of the infantile-erotic

loving and fearing of the parents" (Freud, 1905a, p. 93).

The link between this clarification of his experience (whereby he

lays the foundations of his future theory) and the small clinical jewels

published the following years is obvious. Thus, the phenomena

of psychoanalytic treatmentnotably "On Transitory SymptomConstructions During the Analysis" (Ferenczi, 1912 [85]) and "To

Whom Does One Relate One's Dreams?" (Ferenczi, 1913a [105])

show clearly the plan of transference and countertransference. A little

later, he presents an astonishing opening for different kinds of experimentation in analytic treatment ("Discontinuous Analysis," Ferenczi,

1914 [147]).

Over the following years, the problem of transference was elaborated in the course of a close exchange between Sigmund Freud and

this intuitive, deep, curious, innovative Wise Baby that Ferenczi was

increasingly becoming, even at the price of certain very painful

ordeals. This implies, on the one hand, the discovery through experience of the immense mobilization that transference brings about in a

hidden manner in the two protagonists of the analysis. Freud had

already been thrown off balance by the failure of the Dora case, the

publication of which was a long tale of confusion, ambivalences and

unexpected incidents up until the narrative of the case could finally be

made public in 1905 (see Strachey, 1953, pp. 3-5). The following year

began the story of the "crown prince" Carl Gustav Jung and Sabina

Spielrein, in which Freud became involved (Freud and Jung, 1961;

Carotenuto, 1980). In 1911, it was Ferenczi who fell in love with one

of his patients, Elma Palos.

The pain originated in the affective mobilization of the analyst. As

Freud wrote to Jung:

To be slandered and scorched by the love with which we operate,

such are the perils of our trade, which we are certainly not going

to abandon on their account. Navigare necesse est, vivere non

446

ANDRE HAYNAL

necesse. And another thing: "In league with the Devil and yet

you fear fire?" [Freud and Jung, 1961,134 F, 9.3.1909].

Downloaded by [University of Western Ontario] at 14:53 06 June 2015

A few months later Freud returned to the subject, again to Jung, in the

following terms:

Such experiences, though painful, are necessary and hard to

avoid. Without them we cannot really know life and what we are

dealing with. I myself have never been taken in quite so badly,

but I have come very close to it a number of times and had a

narrow escape [in English in the original]. I believe that only

grim necessities weighing on my work, and the fact that I was ten

years older than yourself when I came to psychoanalysis, have

saved me from similar experiences. But no lasting harm is done.

They help us to develop the thick skin we need and to dominate

"counter-transference", which is after all a permanent problem for

us; they teach us to displace our own affects to best advantage.

They are a 'blessing in disguise'' [in English in the original]

[Freud and Jung, 1961,145 F., 7.6.1925].

It was also in this same letter that the word countertransference is

mentioned for the first time; a year later, it would appear in a

published work (Freud, 1910).

The implications of the affective forces that were clearly at play in

transference led the trio Freud-Jung-Ferenczi towards the occult, a

new pursuit that began during their journey to Clark University in

America in August 1909. Jung's thesis had been on the occult, and as

we have seen, the subject had interested Ferenczi from the outset. It

was hoped that in the intersection of the lines of transference and the

mysteries of the occult, the Gedankenubertragung ("transmission of

thought," or literally "transfer of thought") would shed light on the

Ubertragung (the transference). With his usual enthusiasm, Ferenczi

combed Europe for seers and prophetesses, and Freud participated in

the various experiments; the three took turns playing the role of

medium.

This line of inquiry would not be exhausted for some years. Thus, in

1925, Freud could still remark to Karl Abraham that Anna had a

"telepathic sensitivity" (Freud and Abraham, 1965, 9.7.1925). Nor

Downloaded by [University of Western Ontario] at 14:53 06 June 2015

A METAPSYCHOLOGY OF THE ANALYST

447

should we forget that at the famous meeting of the Secret Committee

in 1921, in the Hartz Mountains, Freud read a memorandum on

"Psychoanalysis and Telepathy," meant only for his intimate circle

and which would only be published posthumously (Freud, 1941).8

For the time being, there was an exchange of ideas on the subject

between Freud and Ferenczi, a kind of exaltation and a resolve to

deepen the impact of affective forces operating in transference and

countertransferencea resolve that apparently was not carried out,

however, to the point that Freud's plan to publish an "Allgemeine

Methodik der Psychoanalyse" (Freud and Ferenczi, 1991, 22 F,

26.11.1908), a general methodology of psychoanalysis, would never

see the light of day. The same held true for the planned work on

metapsychology, and the only works that actually appeared were later

said by Freud to be meant for "beginners" (Blanton, 1971, p. 48) and

essentially negative9 (1113 Fr., 4.1.1928). Since his intuition of genius

had always guided him with the certainty of a sleepwalker, as it were,

one can consider that his renunciation of these two systematic works

(on metapsychology and technique) was not merely indicative of a

failure of synthesis, but of a new way of constructing his theory and of

moving forward in flushing out the deep forces of the human psyche;

it was this ability that gave his work the characteristics of a

postmodern edifice, moving from islet to islet, from insight to insight,

making it, in its very structure, far in advance of the scientific ideals

of his time (Haynal, 1991; Haynal and Falzeder, 1994).10

Ferenczi was always at his side during this period: it was not

coincidence that the crowning of his interest in technique was his

presentation at the Congress of 1918 in Budapest; this also marked the

consecration of Ferenczi's efforts to introduce psychoanalysis to his

8

Freud was supposed to have read his 1922 work on "dreams and telepathy" before the

Viennese Psychoanalytic Society but, for reasons unknown to posterity, did not do so. But the

text, already under press, appeared anyway in Imago (Freud, 1922) (also see Strachey's remarks,

1958, p. 196).

9

"Meine Ratschlage . . . waren wesentlich negativ."

10

It may be worth clarifying that in Freud's Vienna and milieu, the term technique did not

evoke first and foremost technology, as is the case today, but rather technique in the arts, the

technique of the painter or pianist. We should not forget that for Freud, the first Hippocratic

aphorism "Ho biols brakhus, he de tekne makra," in Latin "ars longa, vita brevis" was on everyone's lips, especially among medical students, and that in this context, obviously, "techne"

equals "art." The technique of psychoanalysis, then, is the art of psychoanalysis, as opposed to

its theory.

Downloaded by [University of Western Ontario] at 14:53 06 June 2015

448

ANDRE HAYNAL

city, and no doubt his hour of glory. It was at this same conference

that Freud threw wide open the need for diversification in psychoanalytic technique, notably by saying that it "grew up in the treatment of

hysteria

But the phobias have already made it necessary for us to

go beyond our former limits" (Freud, 1919, p. 165).n

One has the impression that, as of this moment, Freud expected his

students to bring him insights in the technical domain. It is known that

he proposedonly oncea prize for those who would illuminate this

path, especially the links between technique and theory. Already in

1912, he had begged Ferenczi to take charge of this field ("I don't

want to see technique in the hands of Stekel," 272 Fr., 28.1.1912), and

to this end was pleased at the rapprochement between Ferenczi and

Otto Rank ("I am very pleased by the growth of your intimacy with

Rank, it promises good things for the future," 909 Fr., 24.8.1922; and

to Rank on 8.9.1922: "As you know, your alliance with Ferenczi has

my entire sympathy").

The rest is known and followed directly upon the radicalization of

the concept of transference in 1926. In describing the development of

his thought, Ferenczi (1926 [271]) stressed the importance for him and

his analysis of

Rank's suggestion regarding the relation of the patient to the

analyst as the cardinal point of the analytic material and [the

need to] regard every dream, every gesture, every parapraxis,

every aggravation or improvement in the condition of the patient

as above all an expression of transference and resistance [p. 255].

At a more personal level, Ferenczi during this period was dissatisfied with certain aspects of his analysis with Freud and with the

persistence of certain inner problems, notably of a depressive nature,

his depression having taken the form of hypochondriac symptoms. It

was thus that he turned to another fellow analyst, Georg Groddeck,

who became a partner in the exchange of ideas and even in mutual

analysis. It was under the influence of his interactions with Rank and

Groddeck that Ferenczi was able to produce the works that give him

"Earlier, in 1912, h'e stated that "This technique is the only one suited to my individuality;

I do not venture to deny that a physician quite differently constituted might find himself driven

to adopt a different attitude to his patients and to the task before him" (Freud, 1912, p. 111).

Downloaded by [University of Western Ontario] at 14:53 06 June 2015

A METAPSYCHOLOGY OF THE ANALYST

449

his place in the history of psychoanalytic ideas, a place that is only

beginning to be recognized.

Indeed, Ferenczi's contributions were largely ignored by two

generations of analysts, partly as a result of Jones' biography of Freud,

which treated Ferenczi in an entirely inadequate manner. To quote

Balint, "The aftermath of Jones' biography was a spate of acrimonious

publications" (Balint, 1969, p. 220).

The reevaluation of Ferenczi's place is a consequence of the

renewed realization by almost the entire psychoanalytic community of

the central role of transference in analysis. By the same token, there is

the revived importance accorded in analysis to the mother (above and

beyond the oedipal link) and, for many, to traumatism. Historically,

this was part of Ferenczi's legacy in the 1920s, when he was more or

less close to Freud, who moreover recognized on a number of occasions the importance of Ferenczi's contributions. Thus, he said he

"value[d] the joint book [of Ferenczi and Rank] as a corrective of my

view of the role of repetition or acting out in analysis" (Freud and

Abraham, 1965, letter to the Committee, 15.2.1924, p. 345).

Ferenczi's research made it possible to conceive of a field of interactions and finally of intersubjectivity (though, to my knowledge, he

never used the term). But this interactionism never became facile; his

passionate engagement with the Freudian heritage protected him from

that, as well as from the trap of simplification. His various experiments with changing the analyst's role ("active therapy" and "relaxation therapy") were caricatured both in the work of Jones and in other

writings on Ferenczi. But these experiments, along with his realization

of the importance of the psychoanalyst's attitude in the analytic

treatmentwhich could be said to have broken a taboo12 by taking

into, account the analyst's feelings and inner reactionsended up

by centering his interest on countertransference and (its logical

consequence) on the metapsychology of the analyst's mental

processes during analysis, his cathexes, his legitimate pleasures at

work, that is, his way of functioning (Ferenczi, 1928 [283], p. 98),

wanting to create a transparency in this respect, opening up a whole

line of psychoanalytical thinking as it appears in the works of

Winnicott, Little, Heimann, Bion, and the contemporary literature on

12

Although the so-called "neutrality" does not exist in the original writings of Freud, it does

appear in Strachey's English translation.

Downloaded by [University of Western Ontario] at 14:53 06 June 2015

450

ANDRE HAYNAL

countertransference (Coltart, Bollas, etc.), on the emotional experiences of the analyst and their value for a better understanding if the

"dark spots" of his/her analysand. The emphasis put on projective

identification as a means of communication has also in Ferenczi his

forebear (see his Clinical Diary, passim).

His taste for experimentation led him still further, and after a few

experiments of "mutual analysis" with Georg Groddeck,13 he continued "mutual analysis" even with several analysands, keeping a record

of these in his Clinical Journal (Ferenczi, 1985 [1932]).

The direction of Ferenczi's workhis preoccupation with the role

of deepening regressive states, the reliving of traumatism in the

analytical interaction, and above all the central role of countertransference (and hence the need for a metapsychology of the analyst)

became the subject of controversies with Freud, especially from 1927

up to Ferenczi's death (Haynal, 1987, 1991, chap. 12). As Balint

recalls, these controversies were traumatic for the analytic community

and for years were taboo subjects cloaked in silence. Ferenczi, if not

actually erased from the history of psychoanalysisin certain North

American psychoanalytic institutes he was not even taught, remaining

practically unknown to the students14at least he came to be seen

(along with his erstwhile friend Rank) as one of those madmen who,

according to Jones, slipped into psychosis, as in some Greek myth or

drama as punishment for their alleged revolt. In reality, what these

men had dared to do was bring an original contribution to the practice

of psychoanalytic theory.

A part of Ferenczi's legacyhis ideas about countertransference,

traumatism, the metapsychology of the analystwas transplanted by

Michael Balint to London, where it found fertile soil in the English

Middle Group and later reinforced the inquiries of the "Kleinian"

group. Melanie Klein's projective identification of 1946 has its roots

in Ferenczi's work and certainly not in Abraham's. So, too, do the

works of Rosenfeld and Bion (indeed, Bion initiated a contribution to

13

Perhaps he would have also liked to carry out such experiments with Freud. Let us not

forget that when Freud fell ill with his cancer, Ferenczi offered to analyze him, an offer that

touched Freud greatly but that he declined, choosing this time the route of somatic treatment,

among others the Steinach operation supposed to be a hormone therapy (cf. Jones, 1957, p. 104).

14

The tactic of Totschweigenthe silence of death (the idea came to me through a personal

letter from Patrick J. Mahony of 10.2.1991). Clearly, the "political" interests of the movement

get the upper hand, as is the case in other movements (e.g., the "non-persons" of Soviet history).

Downloaded by [University of Western Ontario] at 14:53 06 June 2015

A METAPSYCHOLOGY OF THE ANALYST

451

the metapsychology of the analyst's thought processes as it was

outlined in the wishes of Ferenczi).

In North America, on the other hand, the principal current, egopsychology, haughtily ignored Ferenczi's contributions. This is not

surprising, since Ferenczi warned of the dangers attendant upon an

overly emphasized and unilateral ego-psychology: "The critical

opinion, which has been forming in me during this period, is that

psychoanalysis practices in far too unilateral a fashion . . . a psychology of the Ego" (1165 Fer., 25.12.1929). The fact that Geza Roheim

(1950), in New York, dedicated his monumental Psychoanalysis and

Anthropology to the memory of Sandor Ferenczi may have contributed

to Roheim's remaining virtually unknown in psychoanalytic circles in

his country of adoption until recently. Franz Alexander in Chicago

and Sandor Rado in New York did come back to some aspects of the

Ferenczi heritage, notably through their interest in technique and their

taste for innovation. But it is Clara Thompson, Ferenczi's analysand,

who can be considered his main direct successor on the North American continent, through her general orientation and more specifically

through her articles on countertransference and the role of the

analyst's personality (Thompson, 1956).

In France, no doubt, the work of Jacques Lacan bears the mark of

his reading of Ferenczi, whose role he recognized as being

"inaugural" and who he says "anticipates by far all the themes subsequently developed on the topic" of transference (Lacan, 1958, p. 613),

notably in Ferenczi's work "Introjection and Transference" of 1909.

In recognizing the direct line that leads from Ferenczi to Balint, Lacan

likewise identified a historical continuity: "Outside the foyer of the

Hungarian School with its firebrands now dispersed and soon to be

ashes, only the English in their cold objectivity have been able to

articulate this gaping hole that the neurotic experiences in wanting to

justify his existence, and through that, implicitly to distinguish from

the interhuman relationwith its warmth and its deceptionthis

relationship with the Other where the individual finds his status"

(Lacan, 1958, p. 606).

There is no doubt that Ferenczi enriched the analytic world in the

second part of our century through the attitude that he inauguratedat

the price of a long and sustained inner strugglethat of contact with

one's own experience. He also put theory and the construction of

Downloaded by [University of Western Ontario] at 14:53 06 June 2015

452

ANDRE HAYNAL

hypotheses back where they belong: in a free inquiry on analytic

practice. Thus, it was no longer a question of the introjection of an

authority and its ipse dixit or autos efa, but a beacon in an exchange

between fathers and peers on experience and its formulation. This

leads to a more fraternalor, one might say, a more "egalitarian"

relationship between the analyst and the analysand, which is what

made it possible for Ferenczi to imagine a "mutuality" or "mutual

analysis," even if he quickly had to recognize the limits and the

exceptional nature of such an undertaking.

It has been feared that this passage from the father to the brothers is

an anti-oedipal movement (Grunberger, 1974) and that Ferenczi's

insistance on a "free inquiry" in the spirit of Aufkldrung would endanger the gains of psychoanalysis and ultimately contribute to its banalization. The rapid development of this approach to psychoanalysis in

different cultures and parts of the worldin the British "Middle

Group," in the North American interpersonal school, in certain aspects

of Kohut's self psychology, as well as, especially, in French psychoanalysisand the various degrees of influence exerted in the various

schools, make it clear that the seed has germinated.

To understand the history of psychoanalysis, we can distinguish three

separate strands: a history of the ideas of psychoanalysis, a history of

the persons who thought these ideas, and a history of the

"psychoanalytic movement," that is, the interactions between the

persons who constituted it. Each of these strands can be looked into

independently, although they are tightly interwoven.

Ferenczi, who had anticipated so many Freudian discoveries by

following his intuitions, entered into personal conflict with Freud

because of certain of these intuitions. Freud, of course, was seeking,

quite rightly, to protect his work, but at the same time was having

difficulties followingor perhaps did not intend to followthe

explorations of the man he called his "Grand Vizir"15 (1164 F,

15

Is it possible that Freud's reference to Ferenczi as his "Grand Vizir," the first minister of

the Ottoman Empire, showed a certain ambivalence? After all, the Ottoman Empire was for

centuries the principal enemy of Austria and at that time was still its rival in the Balkans.

Downloaded by [University of Western Ontario] at 14:53 06 June 2015

A METAPSYCHOLOGY OF THE ANALYST

453

13.12.192916). Although the dialogue between the two was never

broken, the crisis witnessed ebbs and flows, and their divergencies

could not be resolved before Ferenczi's death: Freud returned in 1937

to a theme that Ferenczi had been formerly raising (Freud, 1937,

p. 236). Still, the tensions between Ferenczi and the Freud family were

not as important as the other members of the former Secret Committee

seemed to think. A letter from Anna Freud is significant in this regard:

"If there is one man whom I associate with the development of

psychoanalysis, who, for me, is inextricably linked with psychoanalysis itself, it's Ferenczi. My respect and my admiration for his person

and his performance go back so far" (letter from Anna Freud to

Michael Balint, 23.5.1935).17

In 1910, at the Second Congress of Psychoanalysis in Nuremberg,

Freud had used Ferenczi to propose the establishment of the International Psychoanalytical Association. One of Ferenczi's arguments to

the assembly on this occasion was that a grouping of analysts had

become necessary because psychoanalysis, although a "purely scientific question . . . touches so much on the raw the vital foundations of

daily life, certain ideals that have grown dear to us, and dogmas of

family life, school and church" (Ferenczi, 1911 [79], p. 299). Within

such an association, analysts could lend one another support and

exchange experiences without always having to return to the discussion of preliminary hypotheses.

But although Ferenczi went along with Freud's wishes, he was not

taken in. Thus, he (1911) said frankly:

I know the excrescences that grow from organized groups, and I

am aware that in most political, social, and scientific organizations childish megalomania, vanity, admiration of empty formalities, blind obedience, or personal egoism prevail instead of

quiet, honest work in the general interest [p. 302].

On the other hand,

16

"Thus, you have without any doubt distanced yourself from me externally. Internally,

I hope, not to the point that I should expect of you, my Paladin and secret Grand Vizir, a step

towards the creation of a new oppositional analysis."

17

Balint Archives, Geneva.

Downloaded by [University of Western Ontario] at 14:53 06 June 2015

454

ANDRE HAYNAL

The psycho-analytically trained are surely the best adapted to

found an association which would combine the greatest possible

personal liberty with the advantages of family organization. It

would be a family in which the father enjoyed no dogmatic

authority, but only that to which he was entitled by reason of his

abilities and labors. His pronouncements would not be followed

blindly, as if they were divine revelations, but, like everything

else, would be subject to thoroughgoing criticism, which he

would accept, not with the absurd superiority of the paterfamilias, but with the attention that it deserved [p. 303].

The true history of this association, particularly of the Secret Committee of the Seven Ringholders of the elect around Freud that was to

watch over its "policy," in a certain sense is "neither written nor to be

written," to use Lacan's words (Lacan, 1956, p. 474). Perhaps with

one reservation: we are only beginningthrough the various correspondences of Freud's inner circleto understand the unfolding of

events. It seems clear today that the circle of the Ringholders was set

up thanks to the manipulations of Jones, who used the tensions around

Jung to this end (Paskauskas, 1988). It was thus that, little by little,

and notably in the 1920s, Ferenczi was crushed by the political forces

of two ambitions to establish respectable and organized world centers

of psychoanalysisthat of Jones in London, and that of Abraham in

Berlin.

Access to the various correspondences gives us a greater awareness

than in the past of the tensions that existed within Freud's entourage,

and especially within the Secret Committee, between Ferenczi and

(for a certain time) his ally Rank on the one hand, and between

Ferenczi and Jones and Abraham on the other. This is the political

history of the Freudian movement and its clashes between temperaments: Ferenczi, more intuitive and even playful; Abraham, more

conceptual, systematic, of a more classificatory bent; and Jones,

struggling for the scientific respectability of this same psychoanalytic

movement in the English-speaking world. The diverse temperaments

corresponded to diverging positions on the subject of "lay"

nonmedicalanalysis. Freud and Ferenczi were both radically on the

side of lay analysis, while Jones wanted to take more into account the

different sensibility of certain American groups. Abraham and Jones

Downloaded by [University of Western Ontario] at 14:53 06 June 2015

A METAPSYCHOLOGY OF THE ANALYST

455

favored policies institutionalizing analytic training through the

schools they created in Berlin and London; Freud and Ferenczi

remained with the original practitioners: more marginal, more out of

the ordinary, true pioneers lacking a strong desire for organization. On

the one side, a certain conservatism, on the other the aim of deepening

the instrument of analytic treatment and theory at the price of sometimes painful setbacks, which Freud experienced many times and from

which Ferenczi did not shrink. The price of such setbacks, for

Ferenczi, was repeated reappraisalsan ongoing effort to strike a

balance between his desire for authenticity on the one hand and his

wish to take into account institutional considerations on the other.

The institutional tendency was demonstrated in his retrospective in

1928:

Eighteen years ago, the International Psychoanalytical Association was established at my initiative; it groups all those who are

interested in psychoanalysis and who do their best to preserve the

purity of psychoanalysis according to Freud and to develop it as

a separate scientific discipline. In establishing this Association, I

had decided on the principle of admitting only those persons who

adhered to the fundamental theses of psychoanalysis [today,

personal analysis is also a part of the entrance requirements]. I

believed, and I still believe, that a productive discussion is only

possible between people who share the same way of thinking.

Those who have adopted other basic principles as a starting point

would do just as well to have their own center of activity. This

principle, which we continue to apply today, has earned us the

not necessarily flattering term "orthodox", a term to which the

sense of reactionary has been unjustly joined [Ferenczi, 1928

[306], p. 242].

Still, when Freud asked him to accept the presidency of the International Psychoanalytical Association a few years later, in 1932, to

pull him from "the island of dreams where you live with the offsprings

of your imagination" (1216 Fr., 12.5.1932), Ferenczi chose to remain

with the "offsprings of his imagination"to explore his own fantasies

rather than rejoin the "fray," the pathology and vanity of which he had

clearly come to recognize. "I truly believe I can accomplish

Downloaded by [University of Western Ontario] at 14:53 06 June 2015

456

ANDR HAYNAL

something useful by pursuing my present mode of work" (1217 Fer.,

19.5.1932), he wrote. Ferenczi, faithful to his own functioning, his

"metapsychology of the analyst," thus chose to deepen his understanding of the human soul and its mysteries. The Wise Baby, in a last

effort, applied himself to knowing as deeply as possible the baby

within himself, his analysandsin each of us.

Toward the end, in trying better to define his position, he focused

on the problem of orthodoxy (Ferenczi, 1931 [292], p. 98), defining

himself as a "restless spirit" and as the "enfant terrible"18 of psychoanalysis. While stating that "Freud is certainly orthodox" (p. 99), he

hastened to add: "Let us thank the fates that we have the good fortune

to be fellow workers with this great spiritthis liberal spirit, as we

can proclaim him to be" (Ferenczi, 1931 [292], pp. 126-127).

Ferenczi was not to free himself from this ambivalence until the

final year of his life, as witnessed in his Clinical Diary (Ferenczi,

1985), which, according to Balint (Balint, 1969, p. 14), later won the

admiration of Freud. Thus, the straight line represented by the life and

work of Sndor Ferenczi resolved itself in the affirmation of self, in a

conclusion that, in its form, remains as impressionistic and full of

sensitivity and sometimes contradictions as the author himself had

always been. The Wise Baby would remain faithful to himself to the

end: the metapsychology of the/this analyst can be summed up in a

single word: authenticity.

REFERENCES

Balint, M. (1969), Draft introduction. In: The Clinical Diary of Sndor Ferenczi. by S. Ferenczi.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988.

Blanton, S. (1971), Diary of My Analysis with Sigmund Freud. New York: Hawthorn Books.

Carotenuto, A. (1980), A Secret Symmetry. Sabina Spielrein Between Freud and Jung. New

York: Pantheon Books, 1982.

Ferenczi, S. (1899), Spiritizmus. Gyogyaszat, 30:477-479.

(1901), A szerelem a tudomanyban [Love in science]. Gyogyaszat, 41:190-192.

(1902), Homosexualitas feminina. Gyogyaszat, 11:167-168.

(1904a), A hypnosis gyogyitoertekerol [The curative value of hypnosis]. Gyogyaszat,

52:820-822.

(1904b), Ranschburg Pal: A gyenneki elme fejlodese es mkodse, kulonos tekintettel a

lelki rendellenessgekre, ezek elharitasara es orvoslasara (Recensio) [The development and

functioning of the infantile psyche (book review)]. Gyogyasszat, 52:828.

(1908 [63]), Psychoanalysis and education, In: Final Contributions to the Problems and

Methods of Psycho-Analysis, ed. M. Balint. London: Hogarth Press, 1955, pp. 280-290.

18

In French in the text: "terrible child."

Downloaded by [University of Western Ontario] at 14:53 06 June 2015

A METAPSYCHOLOGY OF THE ANALYST

457

(1909 [67], Introjection and transference. First Contributions to Psychoanalysis, ed. M.

Balint. London: Hogarth Press, 1955, pp. 35-93.

(1911 [79]), On the organization of the psychoanalytic movement. Final Contributions

to the Problems and Methods of Psycho-Analysis, ed. M. Balint. London: Hogarth Press,

1955, pp. 299-307.

(1912 [85]), On transitory symptom-constructions during the analysis. First Contributions to Psycho-Analysis, ed. M Balint. London: Hogarth Press, 1955, pp. 193-212.

(1913 [105]), To whom does one relate one's dreams? Further Contributions to the

Theory and Technique of Psycho-Analysis, ed. M. Balint. London: Hogarth Press, 1955, p.

349.

(1913 [111]), Stages in the development of the sense of reality. In: First Contributions

to Psycho-Analysis, ed. M. Balint. London: Hogarth Press, 1955, pp. 213-239.

(1913 [114], A little Chanticleer. First Contributions to Psycho-Analysis, ed. M. Balint.

London: Hogarth Press, 1955, pp. 240-252.

(1914 [147]), Discontinuous analysis. In: Further Contributions to the Theory and

Technique of Psycho-Analysis, ed. M. Balint. London: Hogarth Press, 1955, pp. 233-235.

(1917 [199]), Bartsgom Schchter Miksval [My friendship with Miksa Schchter].

Gyogyaszat, 31:95-104.

(1923 [257]), The dream of the "clever baby." Further Contributions to the Theory and

Technique of Psycho-Analysis, ed. M. Balint. London: Hogarth Press, 1955, p. 349-350.

(1926 [271], Contra-indications to the "active" psycho-analytical technique. In: Further

Contributions to the Theory and Technique of Psycho-Analysis, ed. M. Balint. London:

Hogarth Press, 1955, pp. 217-230.

(1928 [281]), The adaptation of the family to the child. Final Contributions to the

Problems and Methods of Psycho-Analysis, ed. M. Balint. London: Hogarth Press, 1955, pp.

61-76.

(1928 [283]), The elasticity of psycho-analytical technique. Final Contributions to the

Problems and Methods of Psycho-Analysis, ed. M. Balint. London: Hogarth Press, 1955, pp.

87-101.

(1928 [306]), ber den Lehrgang des Psychoanalytikers. Sausteine zur Psychoanalyse,

Band III. Bern: Huber, pp. 422-431, 1964 (Not included in English editions of Ferenczi's

works).

(1929 [287]), The unwelcome child and his death-instinct. In: Final Contributions to

the Problems and Methods of Psycho-Analysis, ed. M. Balint. London: Hogarth Press, 1955,

pp. 102-107.

(1931 [292]), Child analysis of adults. In: Final Contributions to the Problems and

Methods of Psychoanalysis, ed. M. Balint. London: Hogarth Press, 1955, pp. 126-142.

(1932 [308]), Notes and fragments. In: Final Contributions to the Problems and

Methods of Psycho-Analysis, ed. M. Balint. London: Hogarth Press, 1955, pp. 216-279.

(1933 [294]), Confusion of tongues between adults and the child. Final Contributions

to the Problems and Methods of Psycho-Analysis, ed. M. Balint. London: Hogarth Press,

1955, pp. 156-167.

(1934 [296]), On trauma. In: Notes and Fragments. Final Contributions to the Problems

and Methods of Psycho-Analysis, ed. M. Balint. London: Hogarth Press, 1955, pp. 236, 238,

249,253,276.

(1964), Bausteine Bd. I-IV. Bern: Huber.

(1988), The Clinical Diary of Sndor Ferenczi, d. J. Dupont. Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University Press.

Freud, S. (1905a), Jokes and their relation to the unconscious. Standard Edition, 8:9-236.

London: Hogarth Press, 1960.

Downloaded by [University of Western Ontario] at 14:53 06 June 2015

458

ANDR HAYNAL

(1905b), Three essays on the theory of sexuality. Standard Edition, 7:130-243. London:

Hogarth Press, 1953.

Freud, S. (1905c), Fragment of an analysis of a case of hysteria. Standard Edition, 7:1-122.

London: Hogarth Press, 1953.

(1910), The future prospects of psycho-analytic therapy. Standard Edition, 11:141-151.

London: Hogarth Press, 1957.

(1912), Recommendations to physicians practising psycho-analysis. Standard Edition,

12:111-120. London: Hogarth Press, 1958.

(1919), Lines of advance in psycho-analytic therapy. Standard Edition, 17:159-168.

London: Hogarth Press, 1955.

(1922), Dreams and telepathy. Standard Edition, 18.195-220. London: Hogarth Press,

1955.

(1937), Analysis terminable and interminable. Standard Edition, 23:209-253. London:

Hogarth Press, 1964.

(1941 [1921]), Psycho-analysis and telepathy. Standard Edition, 18:173-193. London:

Hogarth Press, 1955.

& Abraham, K. (1965), A Psycho-Analytic Dialogue: The Letters of Sigmund Freud and

Karl Abraham (1907-1926), ed. H. Abraham & E. Freud. New York: Basic Books.

& Jung, C. G. (1961), The Freud/Jung Letters, ed. W. McGuire. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1974.

& Ferenczi, S. (1991, 1996): Correspondence, Vols. 1 &2. Harvard University Press.

Green, A. (1990), Le complexe de castration. Que sais-je? No 2531. Paris: Presses Universitaires

de France.

Grosskurth, P. (1986), Melanie Klein, Her World and Her Work. New York: Knopf.

Grunberger, B. (1974), De la technique active la confusion de langues. Rev. Fran. Psychanal.,

38:521-546.

Haynal, A. (1987), Controversies in Psychoanalytic Method. From Freud and Ferenczi to

Michael Balint. New York: New York University Press, 1989.

(1991), Psychoanalysis and the Sciences. Berkeley: California University Press.

Jones, E. (1957), The Life and Work of Sigmund Freud, Vol. III. London: Hogarth Press.

Jung, C. G. (1906a), Diagnostische Assoziationsstudien. Leipzig: Barth.

(1906b), Psychoanalyse und Assoziationsexperiment (Diagnostische Assoziationsstudien, 6.Beitrag). J. Psychol. Neurol, 7:1-24. (reprinted G. W., vol. 2: 308-337, 1979).

Klein, M. (1946), Notes on some schizoid mechanisms. Internat. J. Psycho-Anal, 27:99-110.

Lacan, J. (1958), La direction de la cure et les principes de son pouvoir. In: Ecrits, Seuil, Paris,

pp. 585-645, 1966 (English: Ecrits. New York: Norton, 1977).

Roheim, G. (1950), Psychoanalysis and Anthropology. New York: International University

Press.

Strachey, J. (1953, 1955, 1958), Standard Edition, 7, 12, 18. London: Hogarth Press.

Thompson, C. (1956), The role of the analyst's personality in therapy. Amer. J. Psychother.,

10:347-359.

Young-Bruehl, E. (1988), Anna Freud. New York: Summit Books.

20 B, Gradelle

CH-1224 Geneva

Switzerland

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Abraham (2014) - A Nepantla Pedagogy - Comparing Anzaldúa BakhtinDocumento21 pagineAbraham (2014) - A Nepantla Pedagogy - Comparing Anzaldúa BakhtinAna InésNessuna valutazione finora

- 2017 Texeira Quilombola Public Policy BrazilDocumento21 pagine2017 Texeira Quilombola Public Policy BrazilAna InésNessuna valutazione finora

- 2013 Bollier CH 2 Quest - For - A - New - Rightsbased - PathwayDocumento27 pagine2013 Bollier CH 2 Quest - For - A - New - Rightsbased - PathwayAna InésNessuna valutazione finora

- 2015 Gibson Fincher Bird MANIFESTO For Living in The AnthropoceneDocumento183 pagine2015 Gibson Fincher Bird MANIFESTO For Living in The AnthropoceneAna InésNessuna valutazione finora

- 2019 Rosset Et Al Agroecology LVC Peasant Agroecology Schools Subject FormationDocumento22 pagine2019 Rosset Et Al Agroecology LVC Peasant Agroecology Schools Subject FormationAna InésNessuna valutazione finora

- 2017 Singh Becoming A Commoner Nov17Documento202 pagine2017 Singh Becoming A Commoner Nov17Ana InésNessuna valutazione finora

- Becker Sociología / Soc VisualDocumento19 pagineBecker Sociología / Soc VisualAna InésNessuna valutazione finora

- 2013 Kaya African Indigenous Knowledge SystemsDocumento16 pagine2013 Kaya African Indigenous Knowledge SystemsAna InésNessuna valutazione finora

- 2002 Walsh The (Re) Articulation of Political Subjectivities and Colonial Difference in EcuadorDocumento39 pagine2002 Walsh The (Re) Articulation of Political Subjectivities and Colonial Difference in EcuadorAna InésNessuna valutazione finora

- Heras Craviotto Espindola Cultures of The 4th GradeDocumento12 pagineHeras Craviotto Espindola Cultures of The 4th GradeAna InésNessuna valutazione finora

- 2011 Read The Production of SubjectivityDocumento19 pagine2011 Read The Production of SubjectivityAna InésNessuna valutazione finora

- Anthropology As Empirical PhilosopyDocumento39 pagineAnthropology As Empirical PhilosopyAna InésNessuna valutazione finora

- 2018 Antuna - What We Talk About When We Talk About Nepantla Gloria Anzald A and The Queer Fruit of Aztec PhilosophyDocumento6 pagine2018 Antuna - What We Talk About When We Talk About Nepantla Gloria Anzald A and The Queer Fruit of Aztec PhilosophyAna InésNessuna valutazione finora

- 1991 Grady Visual Essay and SociologyDocumento17 pagine1991 Grady Visual Essay and SociologyAna InésNessuna valutazione finora

- 1992 Velez Ibañez Greenberg-Anthropology - & - Education - QuarterlyDocumento23 pagine1992 Velez Ibañez Greenberg-Anthropology - & - Education - QuarterlyAna InésNessuna valutazione finora

- 1988 Sands Socioling Analysis of InterviewsDocumento7 pagine1988 Sands Socioling Analysis of InterviewsAna InésNessuna valutazione finora

- Becker Visual Sociology Documentary Photography and Photojournalism 1995 PDFDocumento11 pagineBecker Visual Sociology Documentary Photography and Photojournalism 1995 PDFMartha OrduñoNessuna valutazione finora

- 1992 Velez Ibañez Greenberg-Anthropology - & - Education - QuarterlyDocumento23 pagine1992 Velez Ibañez Greenberg-Anthropology - & - Education - QuarterlyAna InésNessuna valutazione finora

- Beyond Design Ethnography How DesignersDocumento139 pagineBeyond Design Ethnography How DesignersAna InésNessuna valutazione finora

- Lovejoy Chain of BeingDocumento46 pagineLovejoy Chain of BeingAna InésNessuna valutazione finora

- Corragio and Sol Arroyo, 2009Documento12 pagineCorragio and Sol Arroyo, 2009Ana InésNessuna valutazione finora

- EUNIC Yearbook 2012-13 PDFDocumento238 pagineEUNIC Yearbook 2012-13 PDFAna InésNessuna valutazione finora

- Kristeva - Is There A Feminine GeniusDocumento13 pagineKristeva - Is There A Feminine GeniusLady MosadNessuna valutazione finora

- 2018 MartinDocumento69 pagine2018 MartinAna InésNessuna valutazione finora

- Hungary István Deák - The American Historical Review 1992Documento24 pagineHungary István Deák - The American Historical Review 1992Ana InésNessuna valutazione finora

- 1984 Hymes On Goffman PDFDocumento11 pagine1984 Hymes On Goffman PDFAna InésNessuna valutazione finora

- Via Campesina en Annual Report 2015Documento44 pagineVia Campesina en Annual Report 2015Ana InésNessuna valutazione finora

- Carlos ReynosoDocumento12 pagineCarlos ReynosoAna InésNessuna valutazione finora

- 1995 MORENO PsychoanalysisinArgentina (Retrieved - 2015!02!16)Documento4 pagine1995 MORENO PsychoanalysisinArgentina (Retrieved - 2015!02!16)Ana InésNessuna valutazione finora

- A City in Flames and A Community of DestinyDocumento5 pagineA City in Flames and A Community of DestinyAna InésNessuna valutazione finora

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Paper 10: Module No 31: E Text: MHRD-UGC ePG Pathshala - EnglishDocumento16 paginePaper 10: Module No 31: E Text: MHRD-UGC ePG Pathshala - EnglishArvind DhankharNessuna valutazione finora

- Lacan - Seminar XIV The Logic of FantasyDocumento147 pagineLacan - Seminar XIV The Logic of FantasyChris Johnson100% (1)

- Lacan On EngleshDocumento37 pagineLacan On Englesharica82Nessuna valutazione finora

- Lcexpress: Discussions of Her!Documento3 pagineLcexpress: Discussions of Her!velascolucasNessuna valutazione finora

- The Influence of Bion On My Research (Rene Käes)Documento14 pagineThe Influence of Bion On My Research (Rene Käes)JuanOrtiz44Nessuna valutazione finora

- Soler, C. (Article) - About Lacanian AffectsDocumento4 pagineSoler, C. (Article) - About Lacanian AffectsManuela Bedoya Gartner100% (1)

- Miller - On LoveDocumento9 pagineMiller - On Lovesantanu6Nessuna valutazione finora

- What Is Psychoanalytic CriticismDocumento13 pagineWhat Is Psychoanalytic CriticismJoseph HongNessuna valutazione finora

- Name-Of The - Father in Lacanian Psychoanalysis and in JewishtraditionDocumento26 pagineName-Of The - Father in Lacanian Psychoanalysis and in JewishtraditionAdelNessuna valutazione finora

- The Birth of Structuralism From The Analysis of Fairy-TalesDocumento9 pagineThe Birth of Structuralism From The Analysis of Fairy-TalesmangueiralternativoNessuna valutazione finora

- Summary of LacanDocumento3 pagineSummary of LacanFaraz NaqviNessuna valutazione finora

- Foe NotesDocumento5 pagineFoe NotesSour 994Nessuna valutazione finora

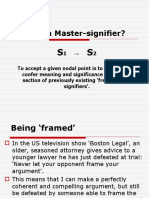

- What Is A Master-Signifier 7 FebDocumento38 pagineWhat Is A Master-Signifier 7 FebEddie DorfmanNessuna valutazione finora

- A Homeless Concept. Shapes of The Uncanny in Twentieth-Century Theory and Culture by Anneleen MasscheleinDocumento10 pagineA Homeless Concept. Shapes of The Uncanny in Twentieth-Century Theory and Culture by Anneleen MasscheleinatelierimkellerNessuna valutazione finora

- Eroticism, Ethics and Reading: Angela Carter in Dialogue With Roland BarthesDocumento154 pagineEroticism, Ethics and Reading: Angela Carter in Dialogue With Roland BarthesYvonne Martinsson100% (1)

- Russell Grigg On The Proper Name As The Signifier in Its Pure State PDFDocumento306 pagineRussell Grigg On The Proper Name As The Signifier in Its Pure State PDFConman ThoughtsNessuna valutazione finora

- Conclusion: Valerie WalkerdineDocumento4 pagineConclusion: Valerie WalkerdinebobyNessuna valutazione finora

- Topology 4Documento13 pagineTopology 4Jenvey100% (1)

- The Autistic Subject On The Threshold of Language 1St Ed Edition Leon S Brenner Full Download ChapterDocumento51 pagineThe Autistic Subject On The Threshold of Language 1St Ed Edition Leon S Brenner Full Download Chaptercindy.parker335100% (5)

- Psychoanalysis and Politics: The Theory of Ideology in Slavoj ŽižekDocumento17 paginePsychoanalysis and Politics: The Theory of Ideology in Slavoj Žižekarunabandara4Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Cinematic Body (1993) 0816622949Documento292 pagineThe Cinematic Body (1993) 0816622949davobrosia100% (3)

- Drive Between Brain and Subject: An Immanent Critique of Lacanian Neuropsychoanalysis - Adrian JohnstonDocumento37 pagineDrive Between Brain and Subject: An Immanent Critique of Lacanian Neuropsychoanalysis - Adrian JohnstonCentro de Atención PsicológicaNessuna valutazione finora

- Marie-Hélène Brousse - FuryDocumento3 pagineMarie-Hélène Brousse - FurytanuwidjojoNessuna valutazione finora

- Barnes and FowelsDocumento291 pagineBarnes and FowelsAida Dziho-SatorNessuna valutazione finora

- Psychoanalytic Film Theory and The RulesDocumento5 paginePsychoanalytic Film Theory and The RulesRafika AlbasitsNessuna valutazione finora

- Hospitality After The Death of God Tracy McNultyDocumento29 pagineHospitality After The Death of God Tracy McNultydekkn100% (1)

- 2001 - The Fright of Real TearsDocumento212 pagine2001 - The Fright of Real Tearsknzssk100% (3)

- Argument FINAL VERSION DISCONTENT AND ANXIETY IN THE CLINIC AND IN CIVILISATIONDocumento5 pagineArgument FINAL VERSION DISCONTENT AND ANXIETY IN THE CLINIC AND IN CIVILISATIONigarathNessuna valutazione finora

- Ragland, Ellie - Hamlet, Logical Time and The Structure of Obsession - 1988Documento9 pagineRagland, Ellie - Hamlet, Logical Time and The Structure of Obsession - 1988Samuel ScottNessuna valutazione finora