Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

How Can Teacher Professional Development Modify Teacher Beliefs To Improve Technology Integration?

Caricato da

robkahlonTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

How Can Teacher Professional Development Modify Teacher Beliefs To Improve Technology Integration?

Caricato da

robkahlonCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Running Head: HOW CAN PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT MODIFY TEACHER BELIEFS

How Can Teacher Professional Development

Modify Teacher Beliefs to Improve Technology Integration?

Robinder Kahlon

University of Ontario Institute of Technology

HOW CAN PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT MODIFY TEACHER BELIEFS

How Can Teacher Professional Development

Modify Teacher Beliefs to Improve Technology Integration?

The integration of technology into the mathematics classroom is governed by a complex set of

factors, two of which are teacher beliefs and teacher professional development. This literature review

will describe the impact of these two factors on technology integration, as well as the exploring the

relationship between the two factors, in an attempt to answer the question: how can teacher professional

development modify teacher beliefs to improve technology integration?

Teachers beliefs and technology integration

With regards to technology integration, several studies have shown that poor integration of

technology in the classroom is correlated with teachers beliefs regarding technologys usefulness.

Thomas (2006) conducted a 10-year longitudinal study of 339 mathematics teachers in New Zealand,

surveying them in 1995 and 2005, to determine the change over time. In the course of ten years, the

proportion of teachers who said that they used computers did not change (67.2% in 1995, 68.4% in

2005). Teachers did use computers more frequently, with 5.9% reporting at least once a week use in

1995, and 13.3% reporting at least once a week use in 2005. The most frequent use of the computers

was for spreadsheet programs and graph-drawing programs, but there was actually a decrease in the use

of mathematical programs and statistical packages. Also, computers were being used frequently for

skills development, and computer use was teacher-directed 80% of the time. For the author, this pattern

of use indicated a poor adoption of technology, and was linked to teacher beliefs. In 2005, very few

teachers believed that computers aided understanding (8%). In fact, significantly more teachers felt that

technology impeded understanding of concepts in mathematics (16%). Instead of using technology to

promote understanding of mathematical concepts, teachers were more inclined to use technology

HOW CAN PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT MODIFY TEACHER BELIEFS

because they felt it made working quicker or more efficient. Teachers felt that the benefits of using

technology were small, that claims about technologies use were exaggerated, and that students relied on

technology too much.

10 years later, more studies show the same pattern: teachers that possess limiting beliefs about

technology and resist the integration of technology in the classroom. In a study by Thomas (2014),

many teachers espoused espouse the belief that technologys usefulness is limited to visualisation,

speed and accuracy of calculation, saving of time and student motivation (Thomas, 2014). They

overemphasized the technical features of technology use and under-emphasize mathematical ideas. The

author characterized these teachers as having low-confidence in the use of technology, and

correspondingly, their technology use in the classroom was low. Another group of teachers espoused

another set of beliefs about technology: believing that technology could help to emphasize the

mathematical ideas present in the lesson, allow students to explore conceptual ideas in mathematics, use

techniques of prediction and testing, instead of calculation and skills practice (Thomas, 2014). These

teachers were termed high-confidence by the author, and demonstrated significant use of technology in

the classroom.

Other studies indicate that the connection between teacher beliefs and classroom practice can be

more complicated than this, however. Teachers may espouse some beliefs about the benefits of

technology use, yet may still be reluctant to use technology in the classroom. Bretscher (2014) found

that teachers were making extensive use of interactive whiteboards but using them as chalkboards or

projectors, and that teachers were only infrequently using computer labs, and when they did use

computer labs with their students, it was often for skills practice. Surprisingly, teachers expressed

positive opinions on the usefulness of technology to improve student engagement, though they were

using technology in a very limited manner. The author speculates that many teachers had a teacher-

HOW CAN PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT MODIFY TEACHER BELIEFS

centered view of the teaching and learning. Because teachers had a preference for traditional, teachercentered practices, they were more willing to incorporate interactive whiteboards into classroom

practice, using them in the same manner as chalkboards had been used in the traditional classroom. The

IWBs were used in a whole-class context with control rarely given to students, supporting the teachercentered model, though by design, IWBs were intended for student interactivity. School computer labs

were used infrequently, seen by teachers as leading to classroom-management problems, giving teachers

a loss of control in the classroom. Even when computers were used, the teachers often provided precise

instructions for their use and had students practice skills instead of investigating mathematical problems

and concepts. Teacher beliefs about technology use were not enacted in actual practice because other

teacher beliefs about pedagogy trumped them.

Bretschers findings concord with the SAMR model (Puentedura, 2014): in the more basic levels

of technology use (substitution and augmentation), technology is used to perform the same functions in

the classroom as the old methods of teaching, leading to little or no increase in student learning

outcomes. These are the methods Bretscher found applied by teacher-centered teachers, or that

Thomas (2014) found used by low-confidence teachers. The higher levels of technology use

(modification and redefinition), in which technology is used to conduct activities that could not be done

without the use of technology, were done by the student-centered teachers in Bretschers study, or by

the high-confidence teachers in Thomas study.

Bretschers study highlights that teachers may have conflicted beliefs so that their teaching

practice does not encompass all of their beliefs, in this case the belief that computer labs are useful for

students. Other studies demonstrate even more strongly teachers who possess beliefs in innovative

teaching practices may not even have the intention to incorporate these innovative practices in their

teaching. Liljedahl (2008), has explored the inconsistencies between teacher beliefs and teacher

HOW CAN PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT MODIFY TEACHER BELIEFS

intentions. In a study of preservice and inservice secondary school mathematics teachers, Liljedahl

found that though teachers espoused innovative views on teaching and learning mathematics, when

asked how they would plan their lessons, they allocated their classroom time to traditional, rule- and

algorithm-based activities. Though Liljedahl did elicit teacher intentions, a shortcoming of his study is

that he did not analyze teachers actual practice in the classroom, leaving open the possibility that

teachers beliefs were eventually realized in classroom practice, despite lack of intentions to do so.

The role of teacher beliefs in affecting teacher practice appears to be poorly understood. While

Thomas (2014) has indicated that negative teacher beliefs about technology integration are correlated to

lack of technology use in the classroom, Bretscher (2014) and Liljedahl (2008) suggest that even

positive teacher beliefs may not lead to changes in teacher practice.

Professional development and Technology Integration

Goos and Bennison surveyed teachers on their use of three technologies in the mathematics

classroom, computers, internet and graphing calculators (Goos and Bennison, 2008). The authors found

that technology-related professional development is positively correlated to use of teachers use of these

three technologies in the classroom but did not establish a causal link between the two. It is possible

that teachers who intend to use technology in the classroom seek out more professional development

than other teachers. However, the importance of professional development to technology integration

was demonstrated by teachers qualitative responses: many teachers in the study expressed the need for

more professional development regarding technology.

While the 2008 study focused on teacher use of technology, a follow-up study, conducted by

Bennison and Goos in 2010, narrowed in on the role of teacher professional development in promoting

the use of technology, and level of teachers confidence levels regarding technology use. Bennison and

Goos surveyed teachers at all 456 secondary schools in Queensland, Australia. Teacher responses were

HOW CAN PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT MODIFY TEACHER BELIEFS

returned from 127 schools, a 28% response rate. used Vygotskys Zone of Proximal Development

(ZPD) model to understand teachers application of technology in the classroom. The authors describe a

teachers ZPD as a set of possibilities for development that are influenced by their mathematical and

pedagogical knowledge and beliefs. (Bennison and Goos, p. 33, 2010). Teacher beliefs, therefore,

define the limits of teacher innovation. Though the authors were hesitant to ascribe a causal relationship

between professional development and teacher confidence, the study found that a correlation exists

(Bennison and Goos, 2010).

Not all technology-focused professional development is successful in motivated technology

integration, however. Mishra and Koehlers TPACK model (Mishra and Koehler, 2006) provides an

effective lens through which to view teachers knowledge in technology integration.

Technology Knowledge, or TK (i.e. how to use technology) is not sufficient to cause successful

technology integration in the classroom. Teachers must have Pedagogical Knowledge, PK (i.e. how to

teach), Content Knowledge, or CK (in this case, mathematical knowledge), and the combination of all 3

types of knowledge, termed Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge, or TPCK.

Recent surveys of teachers support this idea that professional development that focuses on

HOW CAN PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT MODIFY TEACHER BELIEFS

proficiency with technology is insufficient. Handal (2013) surveyed 280 secondary school math

teachers in New South Wales, Australia to determine their proficiency in TCK, TPK and TPCK.

Teachers reported a high TCK, that is in their ability to apply technology to mathematical tasks,

Significantly, their proficiency was in the use of PowerPoint, Excel and Paint. While these 3 software

applications can play a more or less effective role in the teaching of mathematics, there are many more

education-specific technologies in which teachers did not report proficiency, for example: graphing

calculators, interactive whiteboards, dynamic geometry software and computer algebra software.

Teachers TPK scores were lower than their TCK scores. Teachers were less able to use their

knowledge of technology to apply their technology skills for pedagogical purposes (fostering research

skills, fostering collaborative learning, conducting assessment). Finally, teachers TPCK scores were

lower still, meaning that teachers were even less able to guide students in using technology to achieve

learning goals in mathematics (e.g. problem solving, identifying trends in data and predicting, presenting

mathematical concepts).

Many teachers reported their professional development had been too technology-driven, not

pedagogy-driven. The training that teachers desired seemed to be more relevant to identifying

applications for each technology, integrating content and pedagogy. (Handal, p. 33, 2013).

[there is much more in Handal, if needed]

The same division between pedagogically-focused professional developing and technologicallyfocussed professional development is made in Law (2009). The author analyzes the results of the

Second International Information Technology in Education Study 2006 (SITES 2006) which included a

survey of technology use by grade 8 mathematics teachers in 18 countries. The primary factors reported

by teachers was availability and usefulness of professional development opportunities. Teachers who

HOW CAN PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT MODIFY TEACHER BELIEFS

exhibited a higher adoption of technology had participated in pedagogically-focused professional

development, in contrast with teachers with a lower rate of adoption, who had participated in more

technologically-oriented professional development. Moving forward, teachers exhibited more of an

interest in participating in pedagogically-focused professional development. Citing Mishra and Koehler,

the author summarizes the results by recommending that professional development should ensure that

technological and pedagogical skills are not developed in isolation (Mishra and Koehler 2006). (Law,

2009)

In line with the conclusions reached by the authors above who applied the TPACK model,

Thomas (2014) applies an alternative model, the PTK model (pedagogical technology knowledge).

Though using much of the same terminology, Thomas describes creating the PTK model independently

of Mishra and Koehlers TPACK model, though his description of PTK encompasses the same concepts:

PTK includes the need to be a proficient user of the technology, but more importantly, to understand the

principles and techniques required to build didactical situations incorporating it, to enable mathematical

learning through the technology. (Thomas, p. 75, 2014). Thomas analysis has two implications for

teacher professional development: to develop teachers mathematical knowledge and to develop

teachers capacity to use digital technology specifically for the teaching of mathematics.

The Impact of Professional Development on Teacher Beliefs

Goos and Bennisons study, discussed above, proposes a model for the impact of various factors

on technology integration:

HOW CAN PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT MODIFY TEACHER BELIEFS

Figure 1: Factors Affecting Technology Integration

While Goos and Bennisons analysis includes both professional development and pedagogical beliefs as

factors that influence the adoption of technology, the relationship between these factors is not explored

and they appear to be independent of each other.

If professional development could be shown to have a direct impact on pedagogical beliefs,

Figure 1 would be altered as follows:

HOW CAN PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT MODIFY TEACHER BELIEFS

10

Figure 2 Professional development impacts pedagogical beliefs

Research has found, however, that the relationship between professional development and teachers

pedagogical beliefs is more complex than this.

Guskeys model

A model that describes the connection between professional development, change in teacher

practice, and change in teachers beliefs was described by Guskey (2002). Guskey proposes that when

teacher professional development is unsuccessful in changing classroom practice, it may be because of a

lack of appreciation of the motivation for teachers to participate in professional. Teachers are motivated

to improve practice because they want to be better teachers; being a better teacher means improving

student learning outcomes. If a teacher understands that a particular form of professional development

with improve student learning outcomes, that teacher will be motivated to participate in professional

development.

HOW CAN PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT MODIFY TEACHER BELIEFS

11

Guskey states that the change process has been misunderstood. Teacher beliefs cannot directly

be modified through professional development, which will then translate to a change in classroom

practices, which leads to a change in student learning outcomes. The order of these events is incorrect.

Guskey proposes that teacher professional development gives teachers strategies with which to

experiment in the classroom. If the experiment is successful, i.e. if student learning outcomes improve,

then the teachers beliefs are changed. teaching procedures or classroom format. The crucial point is

that it is not the professional development per se, but the experience of successful implementation that

changes teachers attitudes and beliefs. (Guskey, p. 383, 2002).

The model proposes that the feedback provided by improving student achievement is key in the

changing of teachers beliefs, that teachers derive their beliefs about teaching from their classroom

experience. Guskey presents his model in a linear fashion, as follows:

Figure 3 Guskeys model of the indirect relationship between

professional development and pedagogical beliefs

However, employing Goos and Bennisons conclusions that pedagogical beliefs influence classroom

practice, our original model in Figure 1 becomes modified to the following:

HOW CAN PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT MODIFY TEACHER BELIEFS

12

Figure 3 Professional development impacts pedagogical beliefs indirectly

Showing a cycle in which changes in classroom practice impact student achievement, which changes

teachers pedagogical beliefs, which in turn changes classroom practice.

Guskey suggests several implications of this model for professional development:

Recognize that Change is a Gradual and Difficult Process for Teachers

Ensure that Teachers Receive Regular Feedback on Student Learning Progress

Provide Continued Follow-Up, Support and Pressure

Rogers development of Guskeys model

Building upon Guskeys model, Rogers (2007) employs the lens of reflective practice and makes

key modifications. At each stage in the process, a teacher is reflecting on his or her own practice,

causing that teacher to engage in more professional learning. Rogers modifies

HOW CAN PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT MODIFY TEACHER BELIEFS

13

Building reflective practice into professional development echoes what many of the teachers in

the studies discussed above desired about having enough time to digest the new technical skills and a

new mindset. When Bennison and Goos (2010) surveyed teachers regarding their needs around

technology professional development, many teachers (20%) indicated that they needed more time. In

their comments, some teachers expressed that time was even more important than professional

development opportunities. In Thomas 2014 study, teachers also indicated that both they and their

students needed more time to become familiar with new technologies.

Rogers (2007) discussion regarding the development of a professional learning community as

teachers critically examine and reflect on their practice individually, in groups and as a whole staff. (p.

633) also echoes Laws findings. In Laws (2009) study, the success of technology integration was

dependent on the perceived presence of a community of practice (p. 310). Thomas (2014) contends

that that teaching practice PD is best constructed around such a supportive community of inquiry in a

manner that gives teachers the opportunity to observe, practice and reflect on the use of digital

technology in a classroom environment. This last factor is usually missing from the current PD. (p.

86).

HOW CAN PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT MODIFY TEACHER BELIEFS

14

References

Bennison, A., & Goos, M. (2010). Learning to teach mathematics with technology: A survey of

professional development needs, experiences and impacts. Mathematics Education Research

Journal, 22(1), 31-56.

Bretscher, N. (2014). Exploring the Quantitative and Qualitative Gap Between Expectation and

Implementation: A Survey of English Mathematics Teachers Uses of ICT. In The Mathematics

Teacher in the Digital Era (pp. 43-70). Springer Netherlands.

Goos, M., & Bennison, A. (2008). Surveying the technology landscape: Teachers use of technology in

secondary mathematics classrooms.Mathematics Education Research Journal, 20(3), 102-130.

Guskey, T. (2002). Professional development and teacher change. Teachers & teaching: Theory and

Practice, 8(3/4), 381-391.

Handal, B., Campbell, C., Cavanagh, M., Petocz, P., & Kelly, N. (2013). Technological pedagogical

content knowledge of secondary mathematics teachers. Contemporary Issues in Technology and

Teacher Education, 13(1), 22-40.

Law, N. (2009). Mathematics and science teachers pedagogical orientations and their use of ICT in

teaching. Education and Information Technologies,14(4), 309-323.

Liljedahl, P. (2008). Teachers insights into the relationship between beliefs and practice. Beliefs and

attitudes in mathematics education: New research results, 33-44.

Puentedura, R. (2014) Learning, Technology, and the SAMR Model: Goals, Processes, and Practice.

Retrieved from

http://www.hippasus.com/rrpweblog/archives/2014/06/29/LearningTechnologySAMRModel.pd

f

Rogers, P. (2007). Teacher professional learning in mathematics: An example of a change process.

Mathematics: Essential research, essential practice, 631-640.

Thomas, M. O. J. (2006). Teachers using computers in mathematics: A longitudinal study. In J. Novotna,

H. Moraova, M. Kratka, & N. Stehlikova (Eds.), Proceedings of the 30th annual conference of

the International Group Mathematics Education (Vol. 5, pp. 265-272). Prague: PME.

Thomas, M. O., & Palmer, J. M. (2014). Teaching with Digital Technology: Obstacles and

Opportunities. In The Mathematics Teacher in the Digital Era(pp. 71-89). Springer Netherlands.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Law and MoralityDocumento14 pagineLaw and Moralityharshad nickNessuna valutazione finora

- Factors Affecting The Poor Performance in Mathematics of Junior High School Students in IkaDocumento24 pagineFactors Affecting The Poor Performance in Mathematics of Junior High School Students in IkaChris John GantalaoNessuna valutazione finora

- Leadership Action PlanDocumento9 pagineLeadership Action PlanrobkahlonNessuna valutazione finora

- Research Proposal DraftDocumento8 pagineResearch Proposal Draftapi-259463404Nessuna valutazione finora

- Drama Lesson PlanDocumento4 pagineDrama Lesson Planapi-393598576Nessuna valutazione finora

- CH2 David SMCC16ge Ppt02Documento34 pagineCH2 David SMCC16ge Ppt02Yanty IbrahimNessuna valutazione finora

- rtl2 Literature ReviewDocumento11 paginertl2 Literature Reviewapi-357683310Nessuna valutazione finora

- Patient Safety and Quality Care MovementDocumento9 paginePatient Safety and Quality Care Movementapi-379546477Nessuna valutazione finora

- Blended Learning: A Literature ReviewDocumento5 pagineBlended Learning: A Literature Reviewrobkahlon100% (4)

- Director Capital Project Management in Atlanta GA Resume Samuel DonovanDocumento3 pagineDirector Capital Project Management in Atlanta GA Resume Samuel DonovanSamuelDonovanNessuna valutazione finora

- Teachers' technology integration and knowledgeDocumento13 pagineTeachers' technology integration and knowledgeMENU A/P MOHAN100% (1)

- Factors Supporting ICT Use in ClassroomsDocumento24 pagineFactors Supporting ICT Use in ClassroomsSeshaadhrisTailoringNessuna valutazione finora

- Summary Essay of "Professional Writing"Documento2 pagineSummary Essay of "Professional Writing"dope arnoldNessuna valutazione finora

- ABM - AOM11 Ia B 1Documento3 pagineABM - AOM11 Ia B 1Jarven Saguin50% (6)

- ICT and Pedagogy: A Review of The Research LiteratureDocumento43 pagineICT and Pedagogy: A Review of The Research Literatureaamir.saeedNessuna valutazione finora

- Research PaperDocumento14 pagineResearch Paperapi-267483491Nessuna valutazione finora

- Technology in The Classroom: The Impact of Teacher's Technology Use and ConstructivismDocumento13 pagineTechnology in The Classroom: The Impact of Teacher's Technology Use and ConstructivismFarnoush DavisNessuna valutazione finora

- EdEt 780 Research ProjectDocumento18 pagineEdEt 780 Research ProjectjanessasennNessuna valutazione finora

- JC& E - Teacxhers TechnologyDocumento11 pagineJC& E - Teacxhers TechnologymxtxxsNessuna valutazione finora

- Final Jordan EDTECH504 Synthesis PaperDocumento17 pagineFinal Jordan EDTECH504 Synthesis PaperjordnormNessuna valutazione finora

- Literature Review Revision Bofan RenDocumento11 pagineLiterature Review Revision Bofan Renapi-281977500Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ijicte 2019070108Documento14 pagineIjicte 2019070108Nasreen BegumNessuna valutazione finora

- Factors Influencing Teachers' Adoption and Integration of Information and Communication Technology Into Teaching: A Review of The LiteratureDocumento25 pagineFactors Influencing Teachers' Adoption and Integration of Information and Communication Technology Into Teaching: A Review of The LiteratureUzair AhmedNessuna valutazione finora

- Ej 1096803Documento19 pagineEj 1096803Shan Taleah RealNessuna valutazione finora

- Catalyst of ChangeDocumento14 pagineCatalyst of ChangeJasmine ActaNessuna valutazione finora

- Running Head: Collaboration For Professional DevelopmentDocumento6 pagineRunning Head: Collaboration For Professional DevelopmentShawn N. HarrisNessuna valutazione finora

- Impact of ICT Preparation Courses on Pre-Service Teachers' Beliefs and Intentions Toward Technology IntegrationDocumento11 pagineImpact of ICT Preparation Courses on Pre-Service Teachers' Beliefs and Intentions Toward Technology IntegrationLay-an AmorotoNessuna valutazione finora

- MurtaghJim AnnotatedBiblio ConstructivismR2Documento8 pagineMurtaghJim AnnotatedBiblio ConstructivismR2bsujimNessuna valutazione finora

- Mobile Learning EnvironemntsDocumento6 pagineMobile Learning EnvironemntsJames RileyNessuna valutazione finora

- Factors of Professional Staff DevDocumento13 pagineFactors of Professional Staff DevJennifer OestarNessuna valutazione finora

- Wang Weiyin - Moed7053 Assignment 2Documento15 pagineWang Weiyin - Moed7053 Assignment 2codecatkawai123Nessuna valutazione finora

- Computers in Human Behavior: Dirk Ifenthaler, Volker SchweinbenzDocumento10 pagineComputers in Human Behavior: Dirk Ifenthaler, Volker SchweinbenzMadrid MNessuna valutazione finora

- Final AssessmentDocumento17 pagineFinal Assessmentapi-554490943Nessuna valutazione finora

- Using Blackboard in An Educational Psychology Course To Increase Pre-Service Teachers' Skills and Confidence in Technology IntegrationDocumento12 pagineUsing Blackboard in An Educational Psychology Course To Increase Pre-Service Teachers' Skills and Confidence in Technology IntegrationChanwit IntarakNessuna valutazione finora

- Project ResearchDocumento18 pagineProject ResearchArousha SultanNessuna valutazione finora

- Utilization of PhET Interactive Simulations Software of Teachers in Teaching Physics 8 in GovDocumento6 pagineUtilization of PhET Interactive Simulations Software of Teachers in Teaching Physics 8 in GovGlemarie Joy Unico EnriquezNessuna valutazione finora

- EFL Teachers' Beliefs and Practices on ICT IntegrationDocumento12 pagineEFL Teachers' Beliefs and Practices on ICT IntegrationGârimâ YådāvNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 1Documento15 pagineChapter 1Rhea CaasiNessuna valutazione finora

- Asep Budiman, Rani Rahmawati, and Rizky Amalia Ulfa: Asepbudiman@student - Uns.ac - IdDocumento13 pagineAsep Budiman, Rani Rahmawati, and Rizky Amalia Ulfa: Asepbudiman@student - Uns.ac - IdScarletRoseNessuna valutazione finora

- EDTECH 501 - Synthesis PaperDocumento13 pagineEDTECH 501 - Synthesis PaperThomas RobbNessuna valutazione finora

- Tondeur2017 Article UnderstandingTheRelationshipBeDocumento21 pagineTondeur2017 Article UnderstandingTheRelationshipBeFranklin EinsteinNessuna valutazione finora

- Integration of ICT Into Classroom TeachingDocumento4 pagineIntegration of ICT Into Classroom TeachingIbnu Shollah NugrahaNessuna valutazione finora

- Integration of ICT Into Classroom TeachingDocumento4 pagineIntegration of ICT Into Classroom TeachingAnuradhaKannanNessuna valutazione finora

- Professional Development Literature Review Examines Effective PracticesDocumento16 pagineProfessional Development Literature Review Examines Effective PracticesAshwin ThechampNessuna valutazione finora

- Framing Issues Assignment NewDocumento7 pagineFraming Issues Assignment Newapi-372576755Nessuna valutazione finora

- A Study of Teacher Perceptions of Instructional Technology Integration in The Classroom PDFDocumento15 pagineA Study of Teacher Perceptions of Instructional Technology Integration in The Classroom PDFfanaliraxNessuna valutazione finora

- Computers & Education: Syh-Jong Jang, Meng-Fang TsaiDocumento12 pagineComputers & Education: Syh-Jong Jang, Meng-Fang TsaimeditaNessuna valutazione finora

- Guzey Roehrig 2012Documento23 pagineGuzey Roehrig 2012api-345158225Nessuna valutazione finora

- Attitude Towards Life Among Secondary School Students in Relation To Their Parenting StylesDocumento8 pagineAttitude Towards Life Among Secondary School Students in Relation To Their Parenting StylesAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNessuna valutazione finora

- Learning Wipads Building Meaningful EnviromentsDocumento20 pagineLearning Wipads Building Meaningful Enviromentsapi-256818695Nessuna valutazione finora

- Standard 7 rtl2 Assessment 2Documento9 pagineStandard 7 rtl2 Assessment 2api-459491146Nessuna valutazione finora

- Teaching and Teacher Education: Christopher P. Brown, Joanna Englehardt, Heather MathersDocumento12 pagineTeaching and Teacher Education: Christopher P. Brown, Joanna Englehardt, Heather Mathersvampirek91Nessuna valutazione finora

- Research Article 01Documento4 pagineResearch Article 01api-302310036Nessuna valutazione finora

- In-Service Science Teachers' Self-Efficacy and Beliefs About STEM Education: The First Year of ImplementationDocumento18 pagineIn-Service Science Teachers' Self-Efficacy and Beliefs About STEM Education: The First Year of Implementationwhy daNessuna valutazione finora

- Admin,+bate 2010Documento20 pagineAdmin,+bate 2010aboNessuna valutazione finora

- Article Summaries DR ClarkDocumento8 pagineArticle Summaries DR Clarkapi-249448483Nessuna valutazione finora

- Assignment2 Researchandlearnng2 Lisamiller 16085985 Final Final AnotherDocumento13 pagineAssignment2 Researchandlearnng2 Lisamiller 16085985 Final Final Anotherapi-317744099Nessuna valutazione finora

- Teaching MethodologiesDocumento17 pagineTeaching MethodologiesQeha YayaNessuna valutazione finora

- Measuring Teacher Adoption of Effective EdTech StrategiesDocumento34 pagineMeasuring Teacher Adoption of Effective EdTech StrategiesGizem UzundurduNessuna valutazione finora

- Farmer C 2014 PaperDocumento16 pagineFarmer C 2014 PapercaseyfarmerNessuna valutazione finora

- The Viewpoint of School Leader On Self Efficacy Hyflex Learning of TeachersDocumento19 pagineThe Viewpoint of School Leader On Self Efficacy Hyflex Learning of Teachersednalene lariegoNessuna valutazione finora

- Journal ArticleDocumento1 paginaJournal Articleapi-258390586Nessuna valutazione finora

- Uplifting The Performance of Selected Learners Through The Use of Modular Approach and Online Teaching in The New Normal Context and RationaleDocumento23 pagineUplifting The Performance of Selected Learners Through The Use of Modular Approach and Online Teaching in The New Normal Context and RationaleRenante NuasNessuna valutazione finora

- ETEC 533 Framing IssueDocumento6 pagineETEC 533 Framing IssueDoug SmithNessuna valutazione finora

- 2. εκπαίδευση στα δεδομέναDocumento18 pagine2. εκπαίδευση στα δεδομέναsapostolou2Nessuna valutazione finora

- Teacher's Belief-Mix MethodDocumento25 pagineTeacher's Belief-Mix MethodYuliana SuryaNessuna valutazione finora

- Educ 5324-Article 1 Review AktasDocumento4 pagineEduc 5324-Article 1 Review Aktasapi-302418042Nessuna valutazione finora

- Summative Math AssignmentDocumento25 pagineSummative Math Assignmentapi-280269552Nessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction Learning Mathematics Can Be A Struggle For Some Students and The Methods That Educators Use in The Classroom Can Make A Huge Impact On The Level of Understanding For The StudentDocumento7 pagineIntroduction Learning Mathematics Can Be A Struggle For Some Students and The Methods That Educators Use in The Classroom Can Make A Huge Impact On The Level of Understanding For The StudentJosie Enad Purlares CelyonNessuna valutazione finora

- Online Teacher Professional DevelopmentDocumento3 pagineOnline Teacher Professional DevelopmentrobkahlonNessuna valutazione finora

- Technology Leadership PlanDocumento12 pagineTechnology Leadership PlanrobkahlonNessuna valutazione finora

- Running Head: Interview Reflection 1Documento3 pagineRunning Head: Interview Reflection 1robkahlonNessuna valutazione finora

- EDUC5001 - My VisionDocumento16 pagineEDUC5001 - My VisionrobkahlonNessuna valutazione finora

- Impact of Technology On Student/Teacher RolesDocumento6 pagineImpact of Technology On Student/Teacher RolesrobkahlonNessuna valutazione finora

- Comparing Grade 12 Students' Expectations and Reality of Work ImmersionDocumento4 pagineComparing Grade 12 Students' Expectations and Reality of Work ImmersionTinNessuna valutazione finora

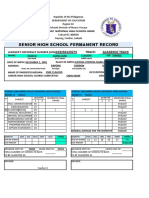

- Form 137 Senior HighDocumento5 pagineForm 137 Senior HighZahjid Callang100% (1)

- Click To Download IELTS Application FormDocumento2 pagineClick To Download IELTS Application Formapi-3712408Nessuna valutazione finora

- Kleincv 090916Documento7 pagineKleincv 090916api-337903620Nessuna valutazione finora

- FY 2023 Gender IssuesDocumento12 pagineFY 2023 Gender IssuesCATALINA DE TOBIONessuna valutazione finora

- Use Your Shoe!: Suggested Grade Range: 6-8 Approximate Time: 2 Hours State of California Content StandardsDocumento12 pagineUse Your Shoe!: Suggested Grade Range: 6-8 Approximate Time: 2 Hours State of California Content StandardsGlenda HernandezNessuna valutazione finora

- Lo CastroDocumento21 pagineLo CastroAlexisFaúndezDemierreNessuna valutazione finora

- Education and It's LegitimacyDocumento13 pagineEducation and It's Legitimacydexter john bellezaNessuna valutazione finora

- Department of Education: Grade & Section Advanced StrugllingDocumento4 pagineDepartment of Education: Grade & Section Advanced StrugllingEvangeline San JoseNessuna valutazione finora

- Strategic Change Management - Processes,: Methods and PrinciplesDocumento60 pagineStrategic Change Management - Processes,: Methods and PrinciplessramuspjimrNessuna valutazione finora

- Eng 149 - Language Learning Materials Development HandoutDocumento45 pagineEng 149 - Language Learning Materials Development HandoutHanifa PaloNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 16 Understanding Specific Needs in Health and Social CareDocumento4 pagineUnit 16 Understanding Specific Needs in Health and Social CareAlley MoorNessuna valutazione finora

- ISM MBA Admission Results 2014Documento7 pagineISM MBA Admission Results 2014SanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Portfolio Darja Osojnik PDFDocumento17 paginePortfolio Darja Osojnik PDFFrancesco MastroNessuna valutazione finora

- Authentic Assessment For English Language Learners: Nancy FooteDocumento3 pagineAuthentic Assessment For English Language Learners: Nancy FooteBibiana LiewNessuna valutazione finora

- Rose Gallo ResumeDocumento1 paginaRose Gallo Resumeapi-384372769Nessuna valutazione finora

- Literary AnalysisDocumento3 pagineLiterary Analysisapi-298524875Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sy 2019 - 2020 Teacher Individual Annual Implementation Plan (Tiaip)Documento6 pagineSy 2019 - 2020 Teacher Individual Annual Implementation Plan (Tiaip)Lee Onil Romat SelardaNessuna valutazione finora

- Grade Sheet For Grade 10-ADocumento2 pagineGrade Sheet For Grade 10-AEarl Bryant AbonitallaNessuna valutazione finora

- Factors Affecting The Deterioration of Educational System in The PhilippinesDocumento6 pagineFactors Affecting The Deterioration of Educational System in The PhilippinesJim Dandy Capaz100% (11)

- Ecd 400 SignatureDocumento8 pagineEcd 400 Signatureapi-341533986Nessuna valutazione finora