Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Rational Consumer Choices

Caricato da

SiphoDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Rational Consumer Choices

Caricato da

SiphoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Chapter 03 - Rational Consumer Choice

Chapter 3 Rational Consumer Choice

Answers to Questions for Review

1. You will be as well off as a year ago; your budget line will remain the same. Your real

income stayed unchanged.

2. False. The slope of the budget constraint tells us only the ratio of the prices of the two goods.

3. False. Diminishing MRS explains the convexity of the indifference curve, but not the

downward slope.

4. You prefer Coke to Diet Coke, Diet Coke to Diet Pepsi, but prefer Diet Pepsi to Coke.

5. The slope of an indifference curve indicates how much of a good one is willing to give up to

get one unit of another and be at the same level of satisfaction. Thus the more of one good

that one is willing to give up, the less important is that good relative to the other.

6. One bundle may be within the individual's opportunity set while the other is not (cannot

afford it).

7. If the relative price of the two goods is not the same as the slope of the indifference curve,

then one will always get a corner solution.

8. True. The corner solution (a) is on a higher indifference curve than the corresponding

tangency (b). Which corner becomes the solution depends on the slope of the budget

3-1

Chapter 03 - Rational Consumer Choice

constraint. There can be a solution in either corner, as shown in the graphs below. Quantity

discounts will not change this outcome scenario.

b

a

X

9. Suppose that Ralph's current consumption bundle is given by the point A in the diagram. The

information given tells us that on the budget with M+10 units of income, Ralph would

consume at the point B, and that B is equally preferred to C. This can happen only if the

indifference curve passing through B and C does not have the usual convex shape. His

indifference curve through B and C could, for example, be a straight line, indicating that tuna

fish and Marshallian money are perfect substitutes in this region. (If the indifference curve

through B and C were convex, then Ralph's optimal bundle would lie between B and C,

which means that he would spend some of the extra R100 on tuna fish.)

Y

M + 100

M

B

A

3-2

Chapter 03 - Rational Consumer Choice

Answers to Chapter 3 Problems

1.

2.

3. a) Pecans are equally preferred to macadamias, which are preferred to almonds, which are

preferred to walnuts, so by transitivity it follows that pecans are preferred to walnuts.

3. b) Macadamias are preferred to almonds and cashews are preferred to almonds. Transitivity

tells us nothing here about the preference ranking of macadamias and cashews.

3-3

Chapter 03 - Rational Consumer Choice

4. True . Each price increases by 15%, so that Px/Py is unchanged. (It is illustrated in the

graph, but it can be answered without drawing the graph.)

Y

M/80

M/92

slope = 120/80 = 3/2

Slope = 138/92 =3/2

M/138 M/120

5. a)

Y

150

60

Milk Balls

5. b) The opportunity cost of an additional unit of the composite good is 1/2.5 = 0.4 bags of milk

balls.

3-4

Chapter 03 - Rational Consumer Choice

6. a)

Y

150

100

60

Milk Balls

6. b) The opportunity cost of a unit of the composite good is now 0.6 bags of milk balls.

7. a)

Y

150

90 Milk Balls

7. b) The opportunity cost of a unit of the composite good is again 0.6 bags of milk balls.

8. a) To get any enjoyment from them, Picabo must consume skis and bindings in exactly the

right proportion. This means that the satisfaction Picabo gets from the bundle consisting of 4

pairs of skis per year and 5 pairs of bindings will be no greater than the satisfaction provided

by the bundle (4, 4). Thus the bundle consisting of 4 pairs of skis per year and 5 pairs of

bindings lies on exactly the same indifference curve as the original bundle. By similar

reasoning, the bundle consisting of 5 pairs of skis per year and 4 pairs of bindings lies on this

indifference curve as well. Proceeding in like fashion, we can trace out the entire

indifference curve passing through the bundle (4, 4), which is denoted as I1 in the diagram.

3-5

Chapter 03 - Rational Consumer Choice

Skis (pairs/yr) 20

16

I4

12

I3

8

5

4

I2

I1

4

12

16

3-6

20 Bindings (pairs/yr)

Chapter 03 - Rational Consumer Choice

b) Skis (pairs/yr)

20

16

I4

12

I3

I2

4

0

I1

4

12

16

18

20 Bindings (pairs/yr)

9. Picabo's budget constraint is B = 15 - 2S. Initially, she needs the same number of pairs of skis

and bindings S = B. Inserting this consumption equation into her budget constraint yields B =

15 - 2B, or 3B = 15, which solves for B = 5 pairs of bindings (and thus S = 5 pairs of skis).

As an aggressive skier, she needs twice as many skis as bindings S = 2B. Inserting this

consumption equation into her budget constraint yields B = 15 - 4B, or 5B = 15, which solves

for B = 3 pairs of bindings (and thus S = 6 pairs of skis). She consumes more skis and fewer

bindings as an aggressive skier than as a recreational skier. See graph below.

Pairs of Bindings per Year (B)

15

B = 15 2S

B=S

5

B = S/2

3

0

5

6

Pairs of Skis per year (S)

3-7

7.5

Chapter 03 - Rational Consumer Choice

10. Alexi's budget constraint is T = 75 - (3/4)C. Her perfect substitute preferences yield linear

indifference curves with slope equal to negative one, such as T = 75 - C and T = 100 - C. By

consuming 900/9 = 100 cups of coffee each month, she reaches a higher indifference curve than

consuming 900/12 = 75 cups of tea (or any affordable mixture of coffee and tea). Thus Alexi

buys 100 cups of coffee and no tea. Any increase in the price of coffee would force Alexi to a

lower indifference curve, and thus lower her standard of living.

Cups of Tea/month

(T)

100

T = 100 C

75

T = 75 (3/4)C

100

Cups of Coffee per month (C)

11. In the diagram, suppose we start at bundle A and then take away P units of pears. How

many more units of apples would we have to give Eve to make her just as happy as at A?

The answer is none, because she didn't care about pears in the first place, and therefore

suffered no loss in satisfaction when we took P units of pears away. Bundle B is thus on the

same indifference curve as bundle A, as are all other bundles on the horizontal line through

A. All of Eve's indifference curves are in fact horizontal lines, as shown.

Apples (kg/wk)

Increasing satisfaction

B A

P

Pears (kg/wk)

3-8

Chapter 03 - Rational Consumer Choice

12. Again start at a given bundle, such as A in the left panel of the diagram below. Then take

away a small amount of food, F, and ask what change in smoke, S, would be required to

restore Kamphelas original satisfaction level. In the standard case, when we take one good

away we need to add more of the other. This time, however, we compensate by taking away

some of the other good. Thus, when we take F units of food away from Kamphela, we must

reduce the smoke level by S in order to restore his original satisfaction level. This tells us

that the indifference curve through A slopes upward, not downward. Kamphela would be just

as happy with a smaller meal served in a restaurant with a no-smoking section as he would

with a larger meal served in a restaurant without one.

It is usually possible to translate the consumer's indifference curves into ones with the

conventional downward slope by simply redefining the undesirable good. Thus, if we might

focus not on smoke, an undesirable good, but on cleanliness (the absence of smoke), which is

clearly desirable. So doing would recast the indifference map in the left panel of the diagram

as the much more conventional-looking one in the right panel.

Food (kg/wk)

Increasing Satisfaction

I3

I2

I1

Food

Increasing Satisfaction

B

A

F

I3

I2

Smoke (micrograms/wk)

I1

Cleanliness

13. You prefer to maximize profit, which is the same under the two rate structures, making you

indifferent between them.

3-9

Chapter 03 - Rational Consumer Choice

14. a) The budget line is B1 and Paula will maximize her utility at the corner solution by attending

10 plays.

M ovies

36

30

24

21

B

0

15

B

1

5

10

12 Plays

14. b) If plays cost R120 and movies cost R40, the budget line is Bo, which has exactly the same

slope as Paula's indifference curves. She will be indifferent between all the bundles on B0.

14. c) On B1, she will consume 10 plays.

15.

Increasing

Y

satisfaction

Y

Increasing

Satisfaction

Garbage

Garbage

16. Let C = coffee (teaspoons/day) and M = Cremora (teaspoons/day). Because of Boris's

preferences, C = 4 M. At the original prices we have:

4M(l) + M(0.5) = 9

4.5M = 9

So M=2 and C=8

3-10

Chapter 03 - Rational Consumer Choice

Let M' and C' be the new values of Cremora and coffee. Again, we know that C'=4M'. With

the new prices we have:

(4M')(3.25) + M'(.5) = 9

13M' + 0.5M' = 9, 13.5M' = 9, M' = 2/3

C = 8/3

17. An unrestricted cash grant would correspond to the budget B1 in the diagram. On B1 the

school would want to spend more than 2M on non-secular activities anyway, so the restriction

will have no effect. This result is analogous to the result in the text concerning the restriction

that food stamps not be spent on cigarettes. Provided the recipient would have spent more on

food than he received in stamps, such a restriction has no effect.

3-11

Chapter 03 - Rational Consumer Choice

Non-secular Activities

14

12

10

B0

B1

8

6

4

2

0

10

18.

19 a) 10(0) + 10(2.50) = R25.00

19. b) 10(2.50) + 10(5.00) = R25 + R50 = R75.

3-12

12

14

16 Secular Activities

Chapter 03 - Rational Consumer Choice

3-13

Chapter 03 - Rational Consumer Choice

20. Your budget constraint is Y = 3 600 - 400C for 0 < C < 5 days of car rental (when you pay the

daily rate), constant at Y = 1 600 for 5 < C < 7 days of car rental (when you switch to the

weekly rate and thus additional days up to one week are free), and then Y = 1 600 - 400(C 7) = 4 400 - 400C for 7 < C < 11 (when again you have to pay by the day for each day

beyond the one week). a) If Y = 1 400C, then inserting this equation into the first leg of the

budget constraint yields 1 400C = 3 600 - 400C or 1 800C = 3 600, which solves for C = 2

days of car rental and thus Y = 2 800 worth of other goods. b) If instead you will trade a day

of car rental for R350, then you would consume a week's rental C = 7 and thus Y = 1 600

worth of other goods. Your seven days of car rental are equivalent to 7(350) = R2 450

according to your preferences, which when added to the R1 600 remaining, yields R4 050.

This beats the R3 600 if you consume no rental days and also beats the 11(350) = R3 850 if

you consume the maximum rental days you can afford (as well as beating any other

affordable combination of C and Y.

Composite Good

per trip (Y)

3600

Problem 20a

Y = 1400C

Y = 3600 400C

2800

Y = 1600

1600

Y = 4400 400C

0

5

7

11

Days of Car Rental per trip (C)

3-14

Chapter 03 - Rational Consumer Choice

Composite Good

per trip (Y)

3600

Problem 20b

Y = 4050 350C

Y = 3600 400C

Y = 1600

1600

Y = 4400 400C

0

5

7

11

Days of Car Rental per trip (C)

21. With diminishing MRS, to decrease pizza consumption from 3 to 2 slices, the consumer has

to be given more than 1 beer (since that was the amount needed to decrease pizza

consumption from 4 to 3 slices and stay on the same indifference curve). So he would be

indifferent between the bundles (3 slices of pizza, 2 beers) and (2 slices of pizza, X beers)

where X>3. However, we know that he prefers (1 slice of pizza, 3 beers) to (3 slices of pizza,

2 beers), so he should also prefer that bundle to (2 slices of pizza, X beers). But this violates

the more-is-better assumption.

3-15

Chapter 03 - Rational Consumer Choice

22. Budget set under Plan A:

Budget set under Plan B:

Notice that Plan A is superior to Plan B since its budget constraint is above the budget

constraint of Plan B.

3-16

Chapter 03 - Rational Consumer Choice

23.

comp osite good

12

11

10

.

.

1

10 11 12 13 14 15 16

Quantity of Soft Drinks

Note that the budget constraint is not a line but rather the set of points that are shown in the

diagram and the ones that are below them. To construct this, for each level of composite

good, from 0 to 12, determine the maximum number of bottles you can buy with the leftover

money. For example, for composite good = 4 units, you have R80 left. The best you can do is

1 large and 1 small, which gives 11 tickets. Remember that you can't buy a fraction of a set.

Notice that point (0, 12) is also on the budget constraint.

24. Assume that the quality of the food is the same in both restaurants, so that price is the only

difference that matters to consumers. In the first restaurant, the R150 flat tip is a fixed cost: it

does not affect the cost of additional items ordered from the menu. In the second restaurant,

by contrast, the price will be 15 per cent higher for each extra item you order. The marginal

cost is higher. The average food bill is R1 000 in the first restaurant, which with tip comes to

R1 150. The same amount of food would cost the same in the second restaurant. But because

3-17

Chapter 03 - Rational Consumer Choice

the cost of each additional item is higher there, we expect that less food will be consumed in

the second restaurant. Note the similarity of this problem to the pizza experiment described in

Chapter 1.

25. Bo is Plane's budget constraint last year. By selling all his grapes he would have an income of

R140 000. By spending all his income on grapes he would have 7000 bu. This year's budget

constraint is B1. It starts at 16 on the Y axis and hits the grapes axis at 16/3, passing through

Y = 10, G = 2, last year's bundle. Since last year's indifference curve (ICo) was tangent to B0

at Y = 10, G = 2, and since this year's budget constraint is steeper than last year's, we know

that some part of last year's IC lies within B1. In particular, a part of ICo that lies above Y =

10, G = 2 is within B1. This means that Plane will consume more Y and less grapes than he

did last year. (See graph on next page.)

3-18

Chapter 03 - Rational Consumer Choice

Y (1000s)

16

14

10

IC0

B1

2

B0

5.33

7 Grapes (1000 bu/yr)

26 Solve the budget constraint, 100 = 4X + l0Y, to get Y = 10 0.4X, then substitute into the

utility function to get U = X(10 0.4X ) = 10X 0.4X2. Equating U/X to zero we have

10 0.8X = 0, which solves for X = 12.5. Substituting back into the budget constraint and

solving for Y, we get Y = 5.

27 The result of solving the budget constraint for Y and substituting back into the utility function

is now U=X1/2(10 0.4X)1/2.

U / X = (1/2)X-1/2(10 0.4X)1/2 + X1/2(1/2)(10 0.4X)-1/2( 0.4) = 0

Rearranging terms, we get (10 0.4X)/X = 0.4, which solves for X = 12.5. Plugging back

into the budget constraint, we get Y = 5. Thus the optimal bundle is (12.5, 5), the same as in

problem 26.

28 Note that the utility function in Problem 26 is simply the square root of the utility

function in Problem 27. Since the square root function is an increasing function, it follows

that the values of X and Y that maximize utility in Problem 26 will also maximize utility in

Problem 27.

3-19

Chapter 03 - Rational Consumer Choice

29 Since we are given the marginal utility per last rand spent on each good, the prices, per

se, do not matter. If Sue spent R1 less on clothing and R1 more on food, her total utility

would change by 9 +12=3. So, no, she cannot be maximizing utility.

30 For Albert to be a utility maximizer, he must allocate his allowance so that the extra

utility per dollar is the same for both the last CD he purchased and the last movie he rented.

As shown in the table, this condition is satisfied when he purchases 2 CDs and rents 3

movies. And since this bundle costs exactly his weekly allowance (2x20 + 3x15 = 85), he is

maximizing his utility.

3-20

Chapter 03 - Rational Consumer Choice

U(N)

MU(N)

MU(N)/PN

M U(M)

MU(M)

MU(M)/PM

__________________________________________________________________

0

0

60

3

20

140

3-21

60

30

15

195

1

4

165

120

105

105

100

20

60

40

210

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Solving Problem Set 3Documento6 pagineSolving Problem Set 3MiiwKotiramNessuna valutazione finora

- Quiz #2 - Week 03/08/2009 To 03/14/2009: 1. Indifference Curves Are Convex, or Bowed Toward The Origin, BecauseDocumento6 pagineQuiz #2 - Week 03/08/2009 To 03/14/2009: 1. Indifference Curves Are Convex, or Bowed Toward The Origin, BecauseMoeen KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Chap006 AppDocumento8 pagineChap006 AppKashif MuhammadNessuna valutazione finora

- Income and Substitution EffectsDocumento39 pagineIncome and Substitution EffectslalaNessuna valutazione finora

- Problem Set 3Documento2 pagineProblem Set 3andre obiNessuna valutazione finora

- Pset For Econ 110Documento4 paginePset For Econ 110Anonymous dRxHeSvyC5Nessuna valutazione finora

- 3550 Ch3Q KeyDocumento6 pagine3550 Ch3Q KeyMohit RakyanNessuna valutazione finora

- Business EconomicsDocumento9 pagineBusiness EconomicsHimanshi YadavNessuna valutazione finora

- Econs 101 - Quiz #2 Answer KeyDocumento1 paginaEcons 101 - Quiz #2 Answer KeySano ManjiroNessuna valutazione finora

- BSM III student analyzes snack budget and indifference curvesDocumento3 pagineBSM III student analyzes snack budget and indifference curvesKimberly Shane AnasariasNessuna valutazione finora

- End-Of-Chapter Answers Chapter 4 PDFDocumento14 pagineEnd-Of-Chapter Answers Chapter 4 PDFSiphoNessuna valutazione finora

- Study Guide CH 7 MicroDocumento35 pagineStudy Guide CH 7 MicroIoana StanciuNessuna valutazione finora

- Microeconomics 2Nd Edition Bernheim Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocumento36 pagineMicroeconomics 2Nd Edition Bernheim Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFcythia.tait735100% (12)

- Problem Set 5 Answers PDFDocumento6 pagineProblem Set 5 Answers PDFrrahuankerNessuna valutazione finora

- Warwick Economics Summer School 2016 Problem Set 1 AnswersDocumento9 pagineWarwick Economics Summer School 2016 Problem Set 1 AnswersAndrew NormandNessuna valutazione finora

- Consumer Choice: Answers To Textbook QuestionsDocumento7 pagineConsumer Choice: Answers To Textbook Questions蔡杰翰Nessuna valutazione finora

- Microeconomics homework on consumer preferencesDocumento3 pagineMicroeconomics homework on consumer preferencesPavel SmirnovNessuna valutazione finora

- Tutorial 1 SolutionDocumento17 pagineTutorial 1 SolutionNikhil Verma0% (1)

- Practice QuestionDocumento10 paginePractice QuestionRajeev SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- Man Kiw Chapter 21 Solutions ProblemsDocumento9 pagineMan Kiw Chapter 21 Solutions Problemswincist67% (3)

- Assignment 3Documento6 pagineAssignment 3wamiqrasheed100% (1)

- Intermediate Microeconomics 1st Edition Mochrie Solutions ManualDocumento74 pagineIntermediate Microeconomics 1st Edition Mochrie Solutions ManualJamesGrantfzdmo100% (19)

- Marginal Utility Analysis Consumer Preference Quantitatively Human Monetary MeasureDocumento7 pagineMarginal Utility Analysis Consumer Preference Quantitatively Human Monetary MeasureRanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Review Session 2Documento3 pagineReview Session 2newsonukumar2003Nessuna valutazione finora

- All Past YeAR PAPERSDocumento131 pagineAll Past YeAR PAPERSmehtashlok100Nessuna valutazione finora

- Solution Manual For Intermediate Microeconomics 1St Edition Robert Mochrie 113700844X 978113700844 Full Chapter PDFDocumento33 pagineSolution Manual For Intermediate Microeconomics 1St Edition Robert Mochrie 113700844X 978113700844 Full Chapter PDFlaura.callaghan623100% (10)

- Chapter 21Documento16 pagineChapter 21Tin ManNessuna valutazione finora

- Intermediate Microeconomics 1st Edition Robert Mochrie 113700844X Solution ManualDocumento113 pagineIntermediate Microeconomics 1st Edition Robert Mochrie 113700844X Solution Manualelvin100% (25)

- Problem Set 1 Solution Key ECN 131Documento4 pagineProblem Set 1 Solution Key ECN 131royhan 312Nessuna valutazione finora

- Curvas de IndifDocumento2 pagineCurvas de IndifJulioMartínezReynosoNessuna valutazione finora

- MIC Tut6Documento5 pagineMIC Tut6Thùy DungNessuna valutazione finora

- ECO2003F: Intermediate Microeconomics Supplementary Examination January 2011 MCQ SectionDocumento12 pagineECO2003F: Intermediate Microeconomics Supplementary Examination January 2011 MCQ SectionSiphoNessuna valutazione finora

- Intermediate Microeconomics 1st Edition Mochrie Solutions ManualDocumento76 pagineIntermediate Microeconomics 1st Edition Mochrie Solutions Manualzxzx111100% (5)

- 20201002181018YWLEE003Consumer Theory SolutionDocumento28 pagine20201002181018YWLEE003Consumer Theory SolutionDương DươngNessuna valutazione finora

- Consumer Theory: Kazi Zayana Arif BSS (Economics), MSS (Economics) University of DhakaDocumento26 pagineConsumer Theory: Kazi Zayana Arif BSS (Economics), MSS (Economics) University of DhakaHussein MubasshirNessuna valutazione finora

- Economics 323-506 March 8, 2005 Exam Part 1: Multiple Choice and Short Answer ProblemsDocumento4 pagineEconomics 323-506 March 8, 2005 Exam Part 1: Multiple Choice and Short Answer ProblemsQudratullah RahmatNessuna valutazione finora

- 456 - Muskan - Valbani - Homework 4Documento4 pagine456 - Muskan - Valbani - Homework 4Muskan ValbaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Microeconomics An Intuitive Approach With Calculus 2nd Edition Thomas Nechyba Test Bank 1Documento7 pagineMicroeconomics An Intuitive Approach With Calculus 2nd Edition Thomas Nechyba Test Bank 1shirley100% (49)

- ME Answer Keys (Problem Set-1) - 2019Documento6 pagineME Answer Keys (Problem Set-1) - 2019Venkatesh MundadaNessuna valutazione finora

- Consumer TheoryDocumento14 pagineConsumer TheoryAndrew AckonNessuna valutazione finora

- Economic Principles - Tutorial 3 AnswersDocumento17 pagineEconomic Principles - Tutorial 3 Answersmad EYES0% (1)

- Problem Set 1Documento9 pagineProblem Set 1Sankar AdhikariNessuna valutazione finora

- Ch05 SolutionsDocumento8 pagineCh05 Solutionsteam.potwNessuna valutazione finora

- The Consumer's Optimal Choice: Pen PalDocumento5 pagineThe Consumer's Optimal Choice: Pen Palnyass thomsonNessuna valutazione finora

- True (See Diagram Below) - Each Price Increases by 15%, So That - Px/Py Is UnchangedDocumento3 pagineTrue (See Diagram Below) - Each Price Increases by 15%, So That - Px/Py Is Unchangedsayoree gooptuNessuna valutazione finora

- Module 2 Tutorial: Q1 Quantity Tax and Food StampsDocumento2 pagineModule 2 Tutorial: Q1 Quantity Tax and Food StampsbavikashiNessuna valutazione finora

- Utility 0Documento117 pagineUtility 0forecellNessuna valutazione finora

- Microeconomics 7th Edition Perloff Test Bank 1Documento34 pagineMicroeconomics 7th Edition Perloff Test Bank 1shirley100% (53)

- MIT14 01SCF11 Assn03Documento3 pagineMIT14 01SCF11 Assn03Vijaya AgrawaNessuna valutazione finora

- ECN201 - Lecture 9Documento31 pagineECN201 - Lecture 9Sapnil Sarker PollobNessuna valutazione finora

- Ba0508 18-19 2 MSTDocumento6 pagineBa0508 18-19 2 MSTccNessuna valutazione finora

- HW 3 AkDocumento10 pagineHW 3 AkUnusualSkillNessuna valutazione finora

- Consumer Behaviour Managerial Economics TutorialDocumento8 pagineConsumer Behaviour Managerial Economics TutorialNitish NairNessuna valutazione finora

- Solution Manual For Microeconomics An Intuitive Approach With Calculus 2Nd Edition Thomas Nechyba 1305650468 9781305650466 Full Chapter PDFDocumento36 pagineSolution Manual For Microeconomics An Intuitive Approach With Calculus 2Nd Edition Thomas Nechyba 1305650468 9781305650466 Full Chapter PDFjose.clark420100% (10)

- 3 Consumerchoice AnsDocumento7 pagine3 Consumerchoice AnsTimothy Mannel tjitraNessuna valutazione finora

- ECON2000: INTERMEDIATE MICROECONOMICS I TUTORIAL SHEET 1Documento6 pagineECON2000: INTERMEDIATE MICROECONOMICS I TUTORIAL SHEET 1Sarah SeunarineNessuna valutazione finora

- PROBLEMS WITH CONSUMER CHOICEDocumento9 paginePROBLEMS WITH CONSUMER CHOICEPavan kumar GulimiNessuna valutazione finora

- 7 II Indifference CurveDocumento3 pagine7 II Indifference Curvesarita sahooNessuna valutazione finora

- Microeconomics - Undergraduate Essays and Revision NotesDa EverandMicroeconomics - Undergraduate Essays and Revision NotesNessuna valutazione finora

- Eco2003f Supp Exam 2013Documento19 pagineEco2003f Supp Exam 2013SiphoNessuna valutazione finora

- ECO2003F: Intermediate Microeconomics Supplementary Examination January 2011 MCQ SectionDocumento12 pagineECO2003F: Intermediate Microeconomics Supplementary Examination January 2011 MCQ SectionSiphoNessuna valutazione finora

- Eco2003f - Supp Exam - 2009 PDFDocumento8 pagineEco2003f - Supp Exam - 2009 PDFSiphoNessuna valutazione finora

- End-Of-chapter Answers Chapter 12Documento12 pagineEnd-Of-chapter Answers Chapter 12SiphoNessuna valutazione finora

- End-Of-Chapter Answers Chapter 9-1 PDFDocumento16 pagineEnd-Of-Chapter Answers Chapter 9-1 PDFSiphoNessuna valutazione finora

- ECO2003F INTERMEDIATE MICROECONOMICS FINAL EXAMDocumento18 pagineECO2003F INTERMEDIATE MICROECONOMICS FINAL EXAMSiphoNessuna valutazione finora

- ECO2003F: Intermediate Microeconomics Examination May/June 2011Documento10 pagineECO2003F: Intermediate Microeconomics Examination May/June 2011SiphoNessuna valutazione finora

- ECO2003F 2015 Tutorial 2 CVWDocumento3 pagineECO2003F 2015 Tutorial 2 CVWSiphoNessuna valutazione finora

- Eco2003f Exam 2010 PDFDocumento10 pagineEco2003f Exam 2010 PDFSiphoNessuna valutazione finora

- ECO2003F: Intermediate Microeconomics Examination May 2009: Total Marks: 240Documento16 pagineECO2003F: Intermediate Microeconomics Examination May 2009: Total Marks: 240SiphoNessuna valutazione finora

- End-Of-Chapter Answers Chapter 10 PDFDocumento13 pagineEnd-Of-Chapter Answers Chapter 10 PDFSiphoNessuna valutazione finora

- End-Of-Chapter Answers Chapter 11 PDFDocumento13 pagineEnd-Of-Chapter Answers Chapter 11 PDFSiphoNessuna valutazione finora

- End-Of-Chapter Answers Chapter 1 PDFDocumento7 pagineEnd-Of-Chapter Answers Chapter 1 PDFSiphoNessuna valutazione finora

- End-Of-Chapter Answers Chapter 6 PDFDocumento7 pagineEnd-Of-Chapter Answers Chapter 6 PDFSiphoNessuna valutazione finora

- End-Of-Chapter Answers Chapter 8 PDFDocumento16 pagineEnd-Of-Chapter Answers Chapter 8 PDFSiphoNessuna valutazione finora

- ECO2003F INTERMEDIATE MICROECONOMICS FINAL EXAMDocumento18 pagineECO2003F INTERMEDIATE MICROECONOMICS FINAL EXAMSiphoNessuna valutazione finora

- End-Of-Chapter Answers Chapter 7 PDFDocumento12 pagineEnd-Of-Chapter Answers Chapter 7 PDFSiphoNessuna valutazione finora

- End-Of-Chapter Answers Chapter 5 PDFDocumento10 pagineEnd-Of-Chapter Answers Chapter 5 PDFSiphoNessuna valutazione finora

- Eco2003f - Supp Exam - 2009 PDFDocumento8 pagineEco2003f - Supp Exam - 2009 PDFSiphoNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 02 - Supply and Demand ExplainedDocumento18 pagineChapter 02 - Supply and Demand ExplainedSiphoNessuna valutazione finora

- Ecos Tut 2Documento2 pagineEcos Tut 2SiphoNessuna valutazione finora

- End-Of-Chapter Answers Chapter 4 PDFDocumento14 pagineEnd-Of-Chapter Answers Chapter 4 PDFSiphoNessuna valutazione finora

- Eco2003f Supp Exam 2013Documento19 pagineEco2003f Supp Exam 2013SiphoNessuna valutazione finora

- ECO2003F: Intermediate Microeconomics Examination May/June 2011Documento10 pagineECO2003F: Intermediate Microeconomics Examination May/June 2011SiphoNessuna valutazione finora

- ECO2003F: Intermediate Microeconomics Supplementary Examination January 2011 MCQ SectionDocumento12 pagineECO2003F: Intermediate Microeconomics Supplementary Examination January 2011 MCQ SectionSiphoNessuna valutazione finora

- ECO2003F: Intermediate Microeconomics Examination May 2009: Total Marks: 240Documento16 pagineECO2003F: Intermediate Microeconomics Examination May 2009: Total Marks: 240SiphoNessuna valutazione finora

- Eco2003f Exam 2010 PDFDocumento10 pagineEco2003f Exam 2010 PDFSiphoNessuna valutazione finora

- Live in MaidDocumento464 pagineLive in MaidnokutendamunashemNessuna valutazione finora

- R Digest Class Capers 1Documento79 pagineR Digest Class Capers 1sarah rasydNessuna valutazione finora

- Group 2Documento13 pagineGroup 2Albert Reyes Doren Jr.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Express Review Guides VocabularDocumento200 pagineExpress Review Guides VocabularIgor R Souza100% (2)

- Basic English Grammar 4th Betty Azar PB PDF 495 576Documento82 pagineBasic English Grammar 4th Betty Azar PB PDF 495 576hanaa bin merdah50% (4)

- Polish Food PresentationDocumento40 paginePolish Food PresentationreguladominikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Receiving DeliveriesDocumento3 pagineReceiving DeliveriesklutgringNessuna valutazione finora

- The PH of Beverages in The United StatesDocumento9 pagineThe PH of Beverages in The United StatesRazty BeNessuna valutazione finora

- Listening Guia # 3 ResueltaDocumento9 pagineListening Guia # 3 ResueltaAlexis Perez CarrascalNessuna valutazione finora

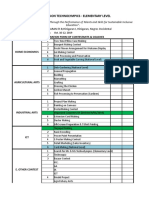

- TECHNOLYMPICSDocumento2 pagineTECHNOLYMPICSArnaldo Esteves HofileñaNessuna valutazione finora

- MRK RSCH 18-28 YR OLDS' BUY HABBITSDocumento11 pagineMRK RSCH 18-28 YR OLDS' BUY HABBITSswagat75Nessuna valutazione finora

- Topic Proposal DraftDocumento4 pagineTopic Proposal DraftChristopher McKinnisNessuna valutazione finora

- Contribution of Systems Thinking and Complex Adaptive System Attributes ToDocumento11 pagineContribution of Systems Thinking and Complex Adaptive System Attributes ToIndra Yusrianto PutraNessuna valutazione finora

- Latihan SoalDocumento7 pagineLatihan SoalSusmi WibowoNessuna valutazione finora

- Korean ReviewerDocumento7 pagineKorean ReviewerOwa DalanonNessuna valutazione finora

- Demon Slayer Planner TemplateDocumento12 pagineDemon Slayer Planner TemplateZahira Mukhtar SyedNessuna valutazione finora

- Pengaruh Umur Induk Dan Lama Penyimpanan Telur Terhadap Bobot Telur, Daya Tetas Dan Bobot Tetas Ayam Kedu Jengger MerahDocumento4 paginePengaruh Umur Induk Dan Lama Penyimpanan Telur Terhadap Bobot Telur, Daya Tetas Dan Bobot Tetas Ayam Kedu Jengger MerahKKN-T Gorontalo 2020Nessuna valutazione finora

- Literature Component Form 4 & 5Documento108 pagineLiterature Component Form 4 & 5mussao8486% (7)

- Rice Paddy Uerb - Google SearchDocumento1 paginaRice Paddy Uerb - Google SearchBrian CeeNessuna valutazione finora

- Exu & Maria Padilla Reina List of HerbsDocumento2 pagineExu & Maria Padilla Reina List of HerbsGnostic the Ancient OneNessuna valutazione finora

- Prepare and Present Bake EggplantDocumento2 paginePrepare and Present Bake EggplantMARK TORRENTENessuna valutazione finora

- M. S. Shanmuganadar Mittai Kadai - ChikkiDocumento10 pagineM. S. Shanmuganadar Mittai Kadai - ChikkiSattur Mittai KadaiNessuna valutazione finora

- Ags 6Documento28 pagineAgs 6hussein harbNessuna valutazione finora

- Design of an Inline Seeder for Conservation AgricultureDocumento102 pagineDesign of an Inline Seeder for Conservation AgricultureMichael Teshome Adebo86% (7)

- Rural Marketing Competitive Strategies-614Documento8 pagineRural Marketing Competitive Strategies-614BharatSubramonyNessuna valutazione finora

- Pembroke June Event 2018 ProgrammeDocumento28 paginePembroke June Event 2018 ProgrammeAran MacfarlaneNessuna valutazione finora

- Sensors 17 02891 PDFDocumento10 pagineSensors 17 02891 PDFWatcharapongWongkaewNessuna valutazione finora

- Boracay Island MicroDocumento10 pagineBoracay Island Microlittles deeperNessuna valutazione finora

- HPC 1 Basic Cuts and ShapesDocumento45 pagineHPC 1 Basic Cuts and ShapesAmie Roncali AlcantaraNessuna valutazione finora

- BUSINESS ETIQUETTE Practice ReadingDocumento2 pagineBUSINESS ETIQUETTE Practice ReadingNguyễn Ngọc DiệpNessuna valutazione finora