Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Zamindars

Caricato da

sourabh singhalCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Zamindars

Caricato da

sourabh singhalCopyright:

Formati disponibili

ZAMINDARS:

The zamindar, a Persian word, became a common term for the landed

gentry along with other terms such as bhumidar, malik or 17th century

onwards, taluqdar, etc.)

Issues a) nature of rights

b) relationship with peasants and state.

Moreland was among the earliest to write on this class of zamindars. He

did not attach much importance to this class and identified them only as

vassal chiefs who accepted Mughal authority. In this he found support by

P.Saran. Such an account stems from certain limitations in his research. It

is only in recent times that work done by Nurul Hassan and I.Habib have

really dwelled on the matter.

Hassan and Habib argue that one cannot equate zamindars with vassal

chiefs simply as they were found everywhere, whether in khalisa land, or

jagir land or paibaqi land. They were not confined to khalisa land. The

zamindars had rights over land and its resources. But these rights were

not proprietary rights and were confined to share in revenue.

The zamindars were also not a homogenous class. Previously the term

zamindars has been used in a generic sense for all peasantry that had

superior rights. They ranged from autonomous or semi-autonomous

chiefs, intermediary zamindars to primary zamindars at the village level.

The differentiation also arose from the degree of acceptance of the

authority of the Mughals.

AUTONOMOUS/ SEMI-AUTONOMOUS CHIEFTAINS

These were the hereditary rulers of certain territories with superior rights

over them. They were also known as ranas, rayas, rawats, etc. No Mughal

authority could afford to completely ignore them. They commanded vast

fiscal and military resources and were therefore, a constant threat to

imperial authority. They were brought under subjugation by military force

by early Sultans. Alauddin Khilji was the one who decided to use

administrative policy to incorporate them.

Any state realised that peasantry could be dealt with only through these

chiefs. They ranged from petty chieftains like the Kachwahas or Prem

Narayan, to very powerful chieftains whose authority extended over large

areas, such as the chiefs of Mewar and Marwar. Some chieftains identified

themselves with the regions they ruled, or by their clan names, such as

the Rathores. There was a very thin line differing the two because clans

often identified themselves with certain territories like the Rathores with

Marwar, Sisodhiyas with Mewar and the Kachwahas with Amer.

An indication of their military strength is evident from contemporary

accounts. Under Babub, 1/6th of revenue came from these chieftains. Arif

Bhandari states that nearly 200-300 rajas commanded strong forces. Abul

Fazl estimated that the total number of forces at the disposal of these

chieftains was 4.4 million.

Their vast resources also supplied possibilities of conflict with the state.

The greater their resources, the greater the protection in resisting the

state.

In the 16th century, with the decline of the Sultanate, these chiefs

constituted a formidable force. Akbar tried to evolve an administrative

system whereby they became part of the Mughal state structure while

also retaining their own territories as watan jagirs. They were expected to

render both military and administrative services in return. They could also

participate actively in the affairs of the Mughal state through this

arrangement. Such an alliance resolved some amount of the conflicts and

dissipated the tension between the state and the chieftains.

There were different levels in this relationship:

Firstly, there were those chieftains who entered into the alliance, and were

consequently given a mansab, military and administrative obligations and

watan jagirs. Their military services could be required to be rendered

anywhere. This category included the likes of the Kachawahas, Jaswant

Singh, etc.

Secondly, there were those chieftains who although enter into an alliance

with the Mughal state, accepting Mughals as the paramount power and

even offer to pay tribute, but are not given a mansab. Their military

service is confined to their own territory and they were not expected to

render military and administrative services to the state.

Thirdly, there were those chieftains who entered into a very limited

alliance. They were not given a mansab nor did they render military

service. They did however, offer to pay tribute and recognized the Mughal

state as paramount power. These were peshkashi chieftains.

N.ASiddiqui has even identified a fourth category, who did not pay tribute,

or recognize the Mughal state as a paramount power. But they did accept

Mughal currency.

MEASURES OF CONTROLLING THEM (AUTONOMOUS/ SEMI-AUTONOMOUS

CHIEFTAINS)

There were several measures used by the Mughal state to keep this

category of zamindars in check ranging from military powers to peshkash

(tribute) in cash or kind. Luxurious items were produced from the area of

chieftains. There was very little information about the value or amount of

peshkash expected and depended on the suitability of that ruler. There

were also no established rules regarding its payment or regularity.

The Mughal overlordship was also expressed in term of personal homage.

Sometimes in case of a tensed relationship, chieftains were forced to send

their sons as hostages to the court. Sometimes the Mughal state entered

into a direct relationship with the vassal states of these chieftains which

automatically undermined the power of bigger chieftains.

Matters pertaining to successions were also decided by the Mughal

emperor, further enforcing his supremacy. While the chieftains had the

independence to govern according to their own customs and traditions,

they were also expected to follow imperial regulations in spheres like

trade, and in dealing with the peasantry. Generally, the imperial orders

and firmans were accepted.

The Mughal concept of watan-jagir played a very important role in these

alliances. It enabled the Mughal state to extend its authority over areas

without assuming responsibility of governance of the same. Thereby it

could also overcome the hostility of the region and gain the best

administrators into its service as well as military contingents.

INTERMEDIARY ZAMINDARS

They existed at the village level, below the chieftains. They did not claim

proprietary right but had malikani rights or right to share in produce.

They were also powerful and commanded huge resources, armed

retainers and contingents. Their main job was to collect the revenue from

the primary zamindars and pass it on to the bigger chieftains. They did

aspire to become autonomous chieftains.

PRIMARY ZAMINDARS

They collected revenue at the village level. They belonged to the class of

the khudkasht peasantry. They were often among the original colonisers of

the area and possessed enough resources. They were known by different

names- muqaddams, chaudhuris, patwaris, etc. they collected revenue

directly from the villagers and aspired to become intermediary zamindars.

Both the intermediary and primary zamindars were ordinary zamindars

whose rights were created over time. Their rights as original colonisers

were thus created on the basis of conquest and were termed as rights

historically created.

RIGHTS ENJOYED BY THE ORDINARY ZAMINDAR:

First and foremost they had malikana rights- or share in produce. While

they were the malik of the land, they did not have proprietary rights.

Even if they did not collect revenue, they had malikana rights as

recognition of their historical rights over the land. While malikana rights

did not bestow proprietorship, they could not be taken away by anyone as

these rights were hereditary.

But in the late 17th century and 18th century, references begin to be made

to the sale and purchase of zamindari rights, which were duly recognized

by the state.

The malikana varied from region to region. There was no common rate at

which it was collected. It could either be collected in kind or in cash. In

some areas where it was collected in kind, it was set as 10 seh per bigha.

Where it was collected as cash, it could be part of revenue or a separate

imposition itself. Sometimes it was the difference between what was

collected and what was due to the state. Mostly, it ranged between 2.5%

to 25% of the produce depending on the productivity and local customary

traditions. For example, in Rajasthan, it was fixed at 2.5%-3% whereas in

fertile areas of northern India it was 10% and higher still in Deccan and

Gujarat at 25% of the produce.

If the zamindars collected revenue on behalf of the state, they were

sometimes entitled to nanka rights- which were allowed only if they

played a crucial role in revenue collection. They even sometimes also

applied additional taxes on birth, marriage, etc. They were in a position to

impose begar as well. Their income was clearly quite lucrative. However it

did not seem so lucrative in comparison to the states income. This is

indicated by the rate at which the zamindari rights were sold.

The origins of zamindari rights were various. They could be created on

basis of conquest of new land. They were also created on basis of force,

annexation of area, subjugation through expansion (as done by Shivaji).

They could be even brought and sold as was the case in the late 17th and

18th centuries. There were very few conditions when the state was

responsible for creating the zamindari rights, such as instances were

rights were granted for expanding cultivation to uncultivated or barren

lands. They could also be granted to control recalcitrant zamindars. For

example, certain Afghan nobles were given zamindari rights in Banswara.

Main features:

Sometimes these rights also had a caste basis, with a tendency of

zamindars belonging to a particular clan to become localised. But in the

Mughal period, social homogeneity of zamidnari rights was eroded

because they became alienable by way of sale and purchase.

The zamindars had direct links with the peasantry on basis of caste/clan

ties.

The rights also had a military basis as most zamindars maintained huge

contingents which enabled them to defy Mughal authority.

According to Irfan Habib, the zamindars exploited the peasantry and they

were the symbols of power and authority in village society. They emerged

even more powerful because of their armed contingents, fortresses, deep

knowledge of customary agrarian practices and caste and clan ties with

peasants, according to Abul Fazl, the total armed strength of zamindars

was 4.2 million.

While ideally, the Mughal state would have wanted direct links with the

peasantry without any intermediaries, it had also realised that the

zamindari class could not be eroded or wholly ignored. The fiscal and

military resources that they commanded made them a powerful and

exploitative class. Therefore the Mughal state was compelled to build a

working relationship with this class.

The zamindars had other responsibilities as well other than collecting

revenue. They were also responsible for maintain revenue records as also

law and order. They were also expected to increase area under cultivation

and invest in agriculture by encouraging cash crops, advancing loans,

hiring out implements to peasantry, building irrigation facilities, etc. This

strengthened the position of the zamindar vis-a-vis the peasantry and the

Mughal state as well. The Mughal state recognized them as a possible

threat but yet, could not ignore them. Many Mughal documents refer to

them as opportunist and rebellious groups but many others also recognize

their significance.

Thus clearly, there was a clash of interest between imperial authority and

the zamindars while both were simultaneously involved in exploiting the

peasant. Those zamindars who had large means and were able to resist

the state, did resist and were known as zamindar-i-zortalab or recalcitrant

zamindars. The state recognized their superior rights and made efforts-

militarily, administratively, through negotiations- to make them part of the

Mughal state for the sake of stability.

The conflict existed at various levels. There was conflict even between the

zamindars themselves. Since they were not a homogenous body, the

conflict took place in form of caste/clan rivalry or between intermediary

zamindars and the chieftains. Conflict could also occur in the process of

acquiring more power and infringing on each others land. Conflict also

arose between the state and the zamindars regarding surplus. While the

bigger zamindars tried to appropriate bigger portions of surplus, the petty

zamindars also tried to appropriate.

The increasing difference between the jama and hasil added on to the

tension and affected the stability of the Mughal state. The zamindars

continuously tried to withhold revenue and the state tried to extract even

more. In certain cases, double extraction by the jagirdar and zamindars

further oppressed the peasantry. For example, in Deccan, the Maratha

collection of the chauth was in addition to the Mughal state tax.

DEVIKA SETHI:- We can observe many contradictory strands existing

together in the tripolar relationships. For instance, the state depended

heavily on zamindars for revenue collection, extension of cultivation and

maintenance of law and order. In this sense, devolution of responsibility

made for more efficient augmentation of resources. However the

enhancement of the powers of zamindars was done at the expense of and

not at the service of the state. This was because the zamindars were

semi-independent entities whose interests did not always coincide with

those of the Mughal state and whose existence also predated the Mughal

state, further cementing their clan/caste ties with the peasantry. Therefore

the state had to balance its reliance on zamindars with its efforts to

undermine their position. Zamindars as a class, with their internal

differentiation, were simultaneously within and without the Mughal

imperial system.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Zamindars Under the MughalsDocumento15 pagineZamindars Under the MughalsGopniya PremiNessuna valutazione finora

- Early Medieval IndiaDocumento19 pagineEarly Medieval IndiaIndianhoshi HoshiNessuna valutazione finora

- Changing Relations With Nobility in Delhi SultanateDocumento7 pagineChanging Relations With Nobility in Delhi SultanateAmala Anna AnilNessuna valutazione finora

- AKBAR S Religious PoliciesDocumento13 pagineAKBAR S Religious PoliciesUrvashi ChandranNessuna valutazione finora

- 18th Century CrisisDocumento6 pagine18th Century CrisisMaryam KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Nayaka Syatem and Agrarian SetupDocumento3 pagineNayaka Syatem and Agrarian SetupPragati SharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- History: (For Under Graduate Student.)Documento16 pagineHistory: (For Under Graduate Student.)Mihir KeshariNessuna valutazione finora

- History Notes by e Tutoriar PDFDocumento53 pagineHistory Notes by e Tutoriar PDFRohan GusainNessuna valutazione finora

- Akbar's conquests unlocked by gunpowderDocumento7 pagineAkbar's conquests unlocked by gunpowderArshita KanodiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Historiographies On The Nature of The Mughal State: Colonialsist HistoriographyDocumento3 pagineHistoriographies On The Nature of The Mughal State: Colonialsist Historiographyshah malikNessuna valutazione finora

- (A) Agricultural Production in Mughal India: Unit 3: Rural Economy and SocietyDocumento17 pagine(A) Agricultural Production in Mughal India: Unit 3: Rural Economy and Societyila100% (1)

- Mansabdari SystemDocumento12 pagineMansabdari SystemFaraz Zaidi100% (1)

- Mansabdari SystemDocumento16 pagineMansabdari SystemAshar Akhtar100% (1)

- Jagir MansabDocumento4 pagineJagir MansabJubin 20hist331Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Marathas Under The Peshwas HistoryDocumento11 pagineThe Marathas Under The Peshwas HistoryShubham SrivastavaNessuna valutazione finora

- Can The Revolt of 1857 Be Described As A Popular Uprising? CommentDocumento5 pagineCan The Revolt of 1857 Be Described As A Popular Uprising? CommentshabditaNessuna valutazione finora

- Persian Sources For Reconstructing History of Delhi SultanateDocumento6 paginePersian Sources For Reconstructing History of Delhi SultanateKundanNessuna valutazione finora

- Jagirdari N CrisisDocumento10 pagineJagirdari N CrisisRichard KeifthNessuna valutazione finora

- Iqta PDFDocumento9 pagineIqta PDFkeerthana yadavNessuna valutazione finora

- The Iqta SystemDocumento5 pagineThe Iqta SystemJahnvi BhadouriaNessuna valutazione finora

- Foundation and Consolidation of The SultanateDocumento10 pagineFoundation and Consolidation of The SultanateYinwang KonyakNessuna valutazione finora

- Inter-Regional and Maritime TradeDocumento24 pagineInter-Regional and Maritime TradeNIRAKAR PATRA100% (2)

- Early Medieval IndiaDocumento10 pagineEarly Medieval IndiaAdarsh jha100% (1)

- Agrarian CrisisDocumento2 pagineAgrarian CrisisAnjneya Varshney100% (2)

- Jagirdari SystemDocumento9 pagineJagirdari SystemSania Mariam100% (6)

- Allauddin Khilji's Market ReformsDocumento4 pagineAllauddin Khilji's Market ReformsPrachi Tripathi 42Nessuna valutazione finora

- Historiography On The Nature of Mughal StateDocumento3 pagineHistoriography On The Nature of Mughal StateShivangi Kumari -Connecting Fashion With HistoryNessuna valutazione finora

- Mughal Decline and AurangzebDocumento21 pagineMughal Decline and AurangzebSaubhik MishraNessuna valutazione finora

- A Study of Persian Literature Under The Mughals in IndiaDocumento5 pagineA Study of Persian Literature Under The Mughals in IndiapoocNessuna valutazione finora

- Mhi 04 Block 02Documento54 pagineMhi 04 Block 02arjav jainNessuna valutazione finora

- Trade in Early Medieval IndiaDocumento3 pagineTrade in Early Medieval IndiaAshim Sarkar100% (1)

- Feudalism DebateDocumento10 pagineFeudalism DebateAshmit RoyNessuna valutazione finora

- Rise of MarathasDocumento21 pagineRise of Marathassajal sanatanNessuna valutazione finora

- VIJAYNAGARDocumento5 pagineVIJAYNAGARSaima ShakilNessuna valutazione finora

- The Nature of State in Medieval South IndiaDocumento11 pagineThe Nature of State in Medieval South IndiaamyNessuna valutazione finora

- Tarikh-i-Firoz ShahiDocumento6 pagineTarikh-i-Firoz ShahiMandeep Kaur PuriNessuna valutazione finora

- VijaynagarDocumento15 pagineVijaynagarsmrithi100% (1)

- The Emergence of Delhi Sultanate by Sunil Kumar PP 1Documento11 pagineThe Emergence of Delhi Sultanate by Sunil Kumar PP 1nitya saxenaNessuna valutazione finora

- IQTA System in Delhi Sultanate - How it Weakened the EmpireDocumento7 pagineIQTA System in Delhi Sultanate - How it Weakened the EmpiresaloniNessuna valutazione finora

- 18th Century As A Period of TransitionDocumento5 pagine18th Century As A Period of TransitionAshwini Rai0% (1)

- Causes of Turkish Success in IndiaDocumento6 pagineCauses of Turkish Success in IndiaDiplina Saharia0% (1)

- Dual Government in Bengal 1765Documento13 pagineDual Government in Bengal 1765Shivangi BoseNessuna valutazione finora

- MalfuzatDocumento3 pagineMalfuzatShristy BhardwajNessuna valutazione finora

- Pinaki Chandra - RMW AssignmentDocumento7 paginePinaki Chandra - RMW AssignmentPinaki ChandraNessuna valutazione finora

- AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTION IN DELHI SULTANATEDocumento5 pagineAGRICULTURAL PRODUCTION IN DELHI SULTANATEsmrithiNessuna valutazione finora

- Economic History of Early Medieval IndiaDocumento52 pagineEconomic History of Early Medieval IndiaALI100% (1)

- Evolution of Political Structures North IndiaDocumento15 pagineEvolution of Political Structures North IndiaLallan SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- Assignment 2Documento5 pagineAssignment 2shabditaNessuna valutazione finora

- Iqta System Features and ChangesDocumento1 paginaIqta System Features and ChangesZoya NawshadNessuna valutazione finora

- Mughal Mansabdari System ExplainedDocumento8 pagineMughal Mansabdari System ExplainedLettisha LijuNessuna valutazione finora

- Medieval India History Reconstructing ResoourcesDocumento9 pagineMedieval India History Reconstructing ResoourcesJoin Mohd ArbaazNessuna valutazione finora

- Indian Feudalism DebateDocumento16 pagineIndian Feudalism DebateJintu ThresiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Rise of IslamDocumento22 pagineRise of IslamayushNessuna valutazione finora

- Perisan Sources in Mughal StudyDocumento3 paginePerisan Sources in Mughal StudyRadhika KushwahaNessuna valutazione finora

- 13th Century NobilityDocumento7 pagine13th Century NobilityKrishnapriya D JNessuna valutazione finora

- Analyzing Market Reforms of Alauddin KhaljiDocumento8 pagineAnalyzing Market Reforms of Alauddin KhaljiDeependra singh RatnooNessuna valutazione finora

- MUGHAL MILITARY TACTICS AND VICTORYDocumento3 pagineMUGHAL MILITARY TACTICS AND VICTORYsatya dewan100% (3)

- Caste and Linguistic Identities in Colonial IndiaDocumento5 pagineCaste and Linguistic Identities in Colonial IndiaAbhinav PriyamNessuna valutazione finora

- Evolution of the Jagirdari System in Mughal IndiaDocumento14 pagineEvolution of the Jagirdari System in Mughal IndiaBasheer Ahamed100% (1)

- The Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India Volume 3 of 4Da EverandThe Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India Volume 3 of 4Nessuna valutazione finora

- GandhiDocumento21 pagineGandhisourabh singhalNessuna valutazione finora

- The Role of Media in Stereotyping WomenDocumento2 pagineThe Role of Media in Stereotyping Womensourabh singhalNessuna valutazione finora

- PollutionDocumento12 paginePollutionsourabh singhalNessuna valutazione finora

- New MediaDocumento1 paginaNew Mediasourabh singhalNessuna valutazione finora

- Comissions During British IndiaDocumento1 paginaComissions During British Indiasourabh singhalNessuna valutazione finora

- Species Richness - : in Amount of Species Between The EcosystemsDocumento8 pagineSpecies Richness - : in Amount of Species Between The Ecosystemssourabh singhalNessuna valutazione finora

- Privacy IntroDocumento27 paginePrivacy Introsourabh singhalNessuna valutazione finora

- Annual Report 2016 - TV 18Documento12 pagineAnnual Report 2016 - TV 18sourabh singhalNessuna valutazione finora

- Indian SociologistsDocumento3 pagineIndian Sociologistssourabh singhalNessuna valutazione finora

- AdvertisingDocumento12 pagineAdvertisingsourabh singhalNessuna valutazione finora

- Network 18Documento9 pagineNetwork 18sourabh singhalNessuna valutazione finora

- Citizenship Is Being Defined As The Relationship Between The State and IndividualsDocumento4 pagineCitizenship Is Being Defined As The Relationship Between The State and Individualssourabh singhalNessuna valutazione finora

- New Media Evolution and Impact in 40 CharactersDocumento5 pagineNew Media Evolution and Impact in 40 Characterssourabh singhalNessuna valutazione finora

- NcertDocumento9 pagineNcertprasad_5353Nessuna valutazione finora

- AdvertisingDocumento12 pagineAdvertisingsourabh singhalNessuna valutazione finora

- Ancient IndiaDocumento11 pagineAncient Indiasourabh singhalNessuna valutazione finora

- Exploring approaches to "the commonsDocumento5 pagineExploring approaches to "the commonssourabh singhalNessuna valutazione finora

- East India Co. Established Three Presidency Banks VizDocumento4 pagineEast India Co. Established Three Presidency Banks Vizsourabh singhalNessuna valutazione finora

- Examine The Extent To Which T H MarshallDocumento3 pagineExamine The Extent To Which T H Marshallsourabh singhalNessuna valutazione finora

- InflationDocumento9 pagineInflationsourabh singhalNessuna valutazione finora

- World GeographyDocumento18 pagineWorld GeographyShravan KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- GDPDocumento6 pagineGDPsourabh singhalNessuna valutazione finora

- Citizenship Is Being Defined As The Relationship Between The State and IndividualsDocumento4 pagineCitizenship Is Being Defined As The Relationship Between The State and Individualssourabh singhalNessuna valutazione finora

- ArchitectureDocumento3 pagineArchitectureYusuf KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- The Concept of Stigma Gained Currency in Social Science Research First Through The Work of Erving GoffmanDocumento13 pagineThe Concept of Stigma Gained Currency in Social Science Research First Through The Work of Erving Goffmansourabh singhalNessuna valutazione finora

- Citizenship Is Being Defined As The Relationship Between The State and IndividualsDocumento4 pagineCitizenship Is Being Defined As The Relationship Between The State and Individualssourabh singhalNessuna valutazione finora

- One India One ElectionDocumento5 pagineOne India One Electionsourabh singhalNessuna valutazione finora

- 18th Century Debates in IndiaDocumento4 pagine18th Century Debates in Indiasourabh singhal86% (7)

- Exploring approaches to "the commonsDocumento5 pagineExploring approaches to "the commonssourabh singhalNessuna valutazione finora

- Child Care Leave G ODocumento4 pagineChild Care Leave G ODISTRICT ELECTION OFFICER KHAMMAMNessuna valutazione finora

- Docs6 ReligiousPersecutionDocumento90 pagineDocs6 ReligiousPersecutionLTTuangNessuna valutazione finora

- Philippine Constitution TimelineDocumento39 paginePhilippine Constitution TimelineMo PadillaNessuna valutazione finora

- Magdala Multipurpose - Livelihood Cooperative and Sanlor Motors Corp. v. Kilusang Manggagawa NG LGS, Magdala Multipurpose - Livelihood CooperativeDocumento14 pagineMagdala Multipurpose - Livelihood Cooperative and Sanlor Motors Corp. v. Kilusang Manggagawa NG LGS, Magdala Multipurpose - Livelihood CooperativeAnnie Herrera-LimNessuna valutazione finora

- CIVIL SERVICE EXAM UPDATE 2023 With Answer Key 2,300 ItemsDocumento302 pagineCIVIL SERVICE EXAM UPDATE 2023 With Answer Key 2,300 ItemsKuyaJemar GraphicNessuna valutazione finora

- List of Shortlisted Candidates For DSSC 27 Selection BoardDocumento12 pagineList of Shortlisted Candidates For DSSC 27 Selection BoardBinde PonleNessuna valutazione finora

- Jurisprudence June 2016Documento11 pagineJurisprudence June 2016Trishia Fernandez GarciaNessuna valutazione finora

- Geeta Kapur - Secular Artist, Citizen ArtistDocumento9 pagineGeeta Kapur - Secular Artist, Citizen ArtistZoe Mccloskey100% (1)

- Mun. Ordinance No. 2008-08. MIPDAC Ordinance (Indigenous)Documento4 pagineMun. Ordinance No. 2008-08. MIPDAC Ordinance (Indigenous)espressoblueNessuna valutazione finora

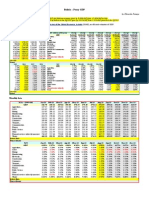

- Bolivia - Proxy GDPDocumento1 paginaBolivia - Proxy GDPEduardo PetazzeNessuna valutazione finora

- Panchayat Samiti (Block) - Wikipedia PDFDocumento3 paginePanchayat Samiti (Block) - Wikipedia PDFJAMESJANUSGENIUS5678Nessuna valutazione finora

- Australia's Economic Freedom Score of 82 Ranks It 3rdDocumento2 pagineAustralia's Economic Freedom Score of 82 Ranks It 3rdjacklee1918Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ang Tibay Vs CIRDocumento2 pagineAng Tibay Vs CIRNyx PerezNessuna valutazione finora

- Department of Electromechanical Engineering Revised Internship Advisor AssignmentDocumento10 pagineDepartment of Electromechanical Engineering Revised Internship Advisor AssignmentkirubelNessuna valutazione finora

- Ammunition Handbook Tactics for Munitions HandlersDocumento254 pagineAmmunition Handbook Tactics for Munitions HandlersHaerul ImamNessuna valutazione finora

- Hosanna Tabor Evangelical Lutheran Church v. EEOCDocumento39 pagineHosanna Tabor Evangelical Lutheran Church v. EEOCDoug MataconisNessuna valutazione finora

- Balance Budget Sim Lesson PlanDocumento5 pagineBalance Budget Sim Lesson Planapi-245012288Nessuna valutazione finora

- COC Checklist FormDocumento1 paginaCOC Checklist Formfuel stationNessuna valutazione finora

- Secretary's Certificate TemplateDocumento2 pagineSecretary's Certificate TemplateJanine Garcia100% (1)

- Pimentel Vs Cayetano NotesDocumento5 paginePimentel Vs Cayetano NotesvestiahNessuna valutazione finora

- 5 - Divine Word University of Tacloban Vs Secretary of Labor and Employment and Divine Word University Employees UNIONALU CONSOLIDATEDDocumento15 pagine5 - Divine Word University of Tacloban Vs Secretary of Labor and Employment and Divine Word University Employees UNIONALU CONSOLIDATEDGoodyNessuna valutazione finora

- The American Pageant Chapter 10 NotesDocumento9 pagineThe American Pageant Chapter 10 Notesvirajgarage100% (3)

- Fixing The Spy MachineDocumento246 pagineFixing The Spy MachineRomeo Lima BravoNessuna valutazione finora

- First International (International Workingmen's Association)Documento2 pagineFirst International (International Workingmen's Association)Sudip DuttaNessuna valutazione finora

- Medical Invitation 1Documento2 pagineMedical Invitation 1Golam Samdanee TaneemNessuna valutazione finora

- America's Unknown Enemy - Beyond - American Institute For EconomicDocumento155 pagineAmerica's Unknown Enemy - Beyond - American Institute For EconomicwestgenNessuna valutazione finora

- Ind Assignment 2 Imr451 PDFDocumento15 pagineInd Assignment 2 Imr451 PDFSaiful Qaza0% (1)

- Diversion of Corporate Opportunity CaseDocumento2 pagineDiversion of Corporate Opportunity Casetsang hoyiNessuna valutazione finora

- Transcript OP HearingDocumento71 pagineTranscript OP HearingDomestic Violence by ProxyNessuna valutazione finora

- 1.-Registration FormDocumento4 pagine1.-Registration FormMinette Fritzie MarcosNessuna valutazione finora