Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Epistaxis

Caricato da

Stephanus AnggaraCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Epistaxis

Caricato da

Stephanus AnggaraCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Turkish Journal of Medical Sciences

http://journals.tubitak.gov.tr/medical/

Research Article

Turk J Med Sci

(2014) 44: 133-136

TBTAK

doi:10.3906/sag-1301-58

Epistaxis in geriatric patients

Alper YKSEL*, Hanifi KURTARAN, Ekrem Said KANKILI, Nebil ARK, Kadriye erife UUR, Mehmet GNDZ

Department of Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, Fatih University, Ankara, Turkey

Received: 14.01.2013

Accepted: 22.02.2013

Published Online: 02.01.2014

Printed: 24.01.2014

Aim: Epistaxis is a common emergency in otolaryngology. The aim of this study is to analyze the etiology, management, and

accompanying disorders of epistaxis in geriatric patients by reviewing the literature

Materials and methods: Data of 117 patients 65 years old and older who presented to the Department of Otorhinolaryngology with

active epistaxis between 2004 and 2010 were retrospectively reviewed. Records were evaluated for age, sex, accompanying disorders,

drug medication, detailed otorhinolaryngological findings, and management of epistaxis.

Results: There were 67 women (57.26%) and 50 men (42.74%) with a mean age of 73.51 years (range: 6590). Ninety-four (80.34%)

patients had accompanying disorders such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cerebrovascular disease, sinusitis, chronic obstructive

lung disease, nasal polyp, and drug treatment. The bleeding site was anterior in 90 patients (76.92%) and posterior in 16 (13.67%). In 11

patients (9.4%), the bleeding site was not identified. Fifty-seven patients (48.71%) were treated with cauterization, 17 patients (14.52%)

with nasal packing, 12 patients (10.25%) with medical treatment, 1 patient (0.85%) with mass excision and nasal packing, and 19

patients (16.23%) with more than 1 treatment method. Six patients (5.12%) were untreated because of the unidentified bleeding point.

Bleeding control was performed under local anesthesia in 113 patients (96.58%) and under general anesthesia in 4 patients (3.41%).

Twenty-one patients (17.94%) were hospitalized and 3 patients (2.56%) required a blood transfusion.

Conclusion: Epistaxis is the most common otorhinolaryngological emergency. It must be evaluated carefully to avoid the potential

complications resulting from both epistaxis and its associated disorders, especially in geriatric patients.

Key words: Epistaxis, cauterization

1. Introduction

Epistaxis is one of the most common nasal emergencies,

with an incidence ranging from 30 to 100 per 100,000

each year (1). The lifetime occurrence rate of epistaxis

is approximately 60% (2). However, most bleeding

episodes are minor and require no medical treatment.

Minor bleeding episodes occur more frequently in

children and adolescents, whereas severe bleeds requiring

otolaryngological intervention often occur in patients

older than 50 years (3).

Anterior nosebleeds are observed in approximately 80%

patients with epistaxis (4). They arise from an anastomosis

called Kiesselbachs plexus in the lower portion of

the anterior septum, called Littles area. Conservative

treatment methods are often sufficient for most patients

with anterior epistaxis. These methods include local

pressure, chemical cautery, and anterior nasal packing (5).

Posterior bleeding originates primarily from the posterior

septal nasal artery, a branch of the sphenopalatine artery,

and tends to be more serious compared with anterior

* Correspondence: alyuksel2003@yahoo.com

bleeding. Conservative methods are generally insufficient

for the treatment of patients with posterior epistaxis, who

often require further otolaryngological intervention (6).

Further treatment options include posterior packing,

arterial ligation, and embolization. Treatment modalities

differ because of factors such as site and severity of

bleeding, predisposing conditions, and experience of the

otolaryngologist.

Various local and systemic factors cause epistaxis.

Common local factors include digital trauma, nasal septal

deviation, neoplasia, inflammation, and chemical irritants,

whereas coagulopathies, renal failure, alcoholism, and

vascular abnormalities are common systemic factors (7,8).

Patients presenting with epistaxis in the geriatric

population must be evaluated carefully. The clinical status

of geriatric patients may deteriorate quickly; therefore,

rapid evaluation and treatment of these patients must be

performed (4).

In this study, the etiology, management, and

accompanying disorders of epistaxis were analyzed in

133

YKSEL et al. / Turk J Med Sci

geriatric patients. A review of the relevant literature is also

presented.

2. Material and methods

The data of 156 patients aged 65 years, who presented

to the Department of Otorhinolaryngology with active

epistaxis between 2004 and 2010, were retrospectively

reviewed. Patients were identified by a search of the

electronic data record system of the hospital. In total, 39

patients were excluded, 22 because they presented with

epistaxis caused by trauma and 17 because of insufficient

data. Therefore, 117 patients with a diagnosis of epistaxis

as confirmed by chart review were eligible for the study.

Epistaxis was defined as bleeding from the nasal cavity as

confirmed by nasal inspection on initial evaluation. The

condition of active or inactive epistaxis was determined on

the basis of the nasal inspection results. The localization of

epistaxis was classified as diffuse or limited and unilateral

or bilateral. The bleeding site was identified as anterior or

posterior after nasal endoscopic examination using 0 and

30 rigid endoscopes. Anterior epistaxis was identified in

cases in which the bleeding site was visible on anterior

rhinoscopy (9).

Patients were labeled positive for hypertension if

this condition was stated in their medical charts or if

they were on antihypertensive medication. Treatment

with anticoagulant medication such as Coumadin,

heparin, Fraxiparine, or aspirin was ascertained during

evaluation. Records were examined to obtain information

regarding age, sex, accompanying disorders, detailed

otorhinolaryngological findings, and management of

epistaxis. This study was approved by the local ethics

committee of the hospital.

3. Results

This study included 67 women (57.26%) and 50 men

(42.74%) with a mean age of 73.51 years (range: 6590

years). Ninety-four (80.34%) patients had accompanying

disorders such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus,

cerebrovascular disease, sinusitis, coronary artery disease,

nasal polyp, or a history of drug medication (Table 1).

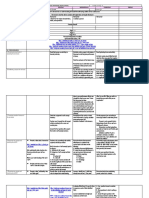

Table 1. Underlying disorders.

Hypertension

91 (77.7%)

Diabetes mellitus

69 (58.9%)

Coronary artery disease

17 (14.5%)

Anticoagulant medication

13 (11.1%)

Sinusitis

11 (9.4%)

Nasal polyp

9 (7.6%)

Cerebrovascular disease

3 (2.5%)

134

The bleeding site was anterior in 90 patients (76.92%)

and posterior in 16 (13.67%). In 11 patients (9.4%), the

bleeding site was not identified. Treatment modalities

used for the management of epistaxis in the patients

included in this study are shown in Table 2. No bleeding

points were identifiable in 6 patients (5.12%). Epistaxis

healed spontaneously in all patients, with no evidence of

recurrence on follow-up. Bleeding control was performed

under local anesthesia in 113 patients (96.58%) and under

general anesthesia in 4 (3.41%). Twenty-one patients

(17.94%) were hospitalized and 3 (2.56%) required a blood

transfusion.

4. Discussion

Bleeding from the nose is a common complaint, and it

occurs in approximately 10% of the population at any given

time (10). Epistaxis may lead to mortality and morbidity in

vulnerable groups such as children and the elderly and in

patients with additional systemic disorders.

The interaction of several local and systemic factors

results in nosebleeds. These factors damage the nasal

mucosa, affect the vascular structure, and/or disrupt blood

clotting. They include environmental conditions, trauma,

nasal septal deviation, tumors, inflammation, bleeding

disorders, anticoagulant medications, hypertension,

and age. In geriatric patients, systemic factors such as

hypertension, advanced age, and bleeding disorders

are the most common causes of serious epistaxis (7,8).

Vascular wall changes associated with ageing, such as

fibrosis of the arterial tunica media, have been implicated

in the development of epistaxis. Therefore, elderly patients

are at higher risk of epistaxis (11).

The prevalence of hypertension in patients with

epistaxis reportedly ranges from 24% to 64% (12).

Another controlled study provided a relationship between

epistaxis and high blood pressure (13). In contrast, a crosssectional study in patients with hypertension found no

independent association between the severity of epistaxis

and hypertension (14). Other studies have suggested that

hypertension in patients with epistaxis may be related

to anxiety (15). Ninety-one (77.7%) of the 117 patients

in our study group had a history of epistaxis. The role of

hypertension in epistaxis is controversial, and the evidence

available is insufficient to prove a significant association

between hypertension and epistaxis. However, the

control of epistaxis may be more difficult in patients with

hypertension (7).

In rare cases, epistaxis may be a life-threatening

emergency, especially in elderly patients with hypertension

and severe hemorrhage (10). In our study group, none of

the patients required resuscitation despite old age (>65

years old) and underlying disorders (80.34% patients).

Coagulation screening is not routinely used in our

institution. Studies have shown that routine coagulation

YKSEL et al. / Turk J Med Sci

Table 2. Treatment modalities.

SN

Anterior

Posterior

48

EC

AP

10

PP

MT

12

SN + AP

ME + AP

17

SN = silver nitrate, EC = electrocautery, AP = anterior packing, PP =

posterior packing, MT = medical treatment, ME = mass excision.

studies such as prothrombin time and activated partial

thromboplastin time are not necessary in patients with

epistaxis. Coagulation screening should be used in

patients with suspected clotting disorders or in patients

who receive anticoagulation treatment (16,17).

The first step in the treatment of acute epistaxis is

identification of the bleeding point. In our study, 90

(76.92%) of the patients had anterior epistaxis. This

incidence rate is compatible with the rates reported in

the literature (4). After localization of the bleeding point,

chemical cautery or electrocautery can be performed.

Silver nitrate can be used as a chemical cauterization

agent, especially for minor bleeding, with minimal

discomfort. Electric cauterization must be performed

for more aggressive bleeding from the anterior septum.

Cauterization should be one-sided in order to prevent

septal perforation (18). There is no evidence to prove that

electrocautery has any advantage over silver nitrate cautery

(10). In our study group, 90 (76.92%) patients had anterior

epistaxis, 48 (41.02%) of whom were successfully treated

with silver nitrate cautery. Only 2 patients were treated

with electrocautery because of severe epistaxis from the

anterior septum.

In the case of cauterization failure, nasal packing

must be considered as the next treatment option. Many

different types of packs are available, including absorbable,

nonabsorbable, anterior, and posterior packs. Common

absorbable materials used for anterior packing include

oxidized cellulose (e.g., Surgicel, Johnson & Johnson,

New Brunswick, NJ, USA) and gelatin foams (e.g.,

Gelfoam, Pfizer, New York, NY, USA). Another product

that combines thrombin with gelatin (e.g., Floseal, Baxter

Health Care Corp, Deerfield, IL, USA) is used as a highviscosity gel for hemostasis (19). All these absorbable

products are easily used and cause minimal pain and

discomfort.

Various kinds of nonabsorbable packing materials

are also available, including inflatable balloons, calcium

alginate, polyvinyl alcohol (e.g., Merocel, Medtronic

XOMED, Jacksonville, FL, USA), and petroleum jellyimpregnated gauze. The major disadvantage of anterior

packing with these materials is the need for removal

of the material and the pain associated with placement

and removal. Complications caused by anterior packs

include ulcerations, septal perforation, sinusitis, synechia,

hypoxemia, and arrhythmias (20). Contrarily, Kurtaran

et al. reported that nasal packing with airway tubes is

not a cause for postoperative respiratory dysfunction and

hypoxia (21). Merocel is most commonly used for anterior

packing in our institution. None of the complications

mentioned above were observed in this study, although

our study group comprised geriatric patients.

Approximately 10% of all nosebleeds arise from the

posterior part of the nose (22). Posterior epistaxis is often

encountered in elderly individuals (23). This condition

may be associated with diseases such as hypertension and

arterial degeneration (24). In our study group, 16 (13.67%)

patients had posterior epistaxis. Although no research on

epistaxis in geriatric patients is available, the incidence

of posterior epistaxis in this study was not significantly

higher than that in the normal population. In this study,

a formal posterior pack made of ribbon gauze was used in

2 patients, although balloon catheters are more commonly

used. However, posterior packing is associated with

increased risk of mortality and morbidity. Nasal packing

may cause significant hypoxia, especially in patients with

chronic systemic disorders (10).

In some cases, traditional nasal packing fails to control

the epistaxis. Angiographic embolization or endoscopic

techniques for sphenopalatine artery ligation can be used

for the control of intractable bleeding. Angiographic

embolization for posterior epistaxis was first described

in 1974 (25), with success rates ranging from 79% to 96%

(26). Complications of embolization include rebleeding,

stroke, blindness, facial numbness, skin sloughing, and

groin hematoma. A success rate of 98% was reported for

endonasal ligation of the sphenopalatine artery to control

bleeding in 127 patients; no significant treatment-related

complications were reported in that study (27). In our study,

all patients with epistaxis were treated using conventional

methods. No further interventions such as embolization

or sphenopalatine artery ligation were required.

Some authors recommend a formal nasal examination

under general anesthesia in patients with posterior

epistaxis (23). In our study group, only 4 (3.41%) of the

16 (13.6%) patients with posterior epistaxis were treated

under general anesthesia. In fact, treatment of epistaxis

under general anesthesia is easier than treatment under

135

YKSEL et al. / Turk J Med Sci

local anesthesia for both the surgeon and the patient;

however, general anesthesia can be dangerous for geriatric

patients with systemic disorders. Bleeding control was

performed under local anesthesia in 113 patients (96.58%).

Twenty-one patients (17.94%) were hospitalized and 3

(2.56%) required a blood transfusion.

In conclusion, epistaxis, which is the most common

otorhinolaryngological emergency, must be evaluated

carefully to avoid the potential complications resulting

from both epistaxis and its associated disorders, especially

in geriatric patients. Multiple methods for treating anterior

and posterior epistaxis are available, and occasionally

more than one treatment is used. Otolaryngologists must

be prepared to deal with severe bleeding through the use

of medications, packing materials, and radiological or

surgical interventions, especially in geriatric patients.

References

1.

ODonnell M, Robertson G, McGarry GW. A new bipolar

diathermy probe for the outpatient management of adult acute

epistaxis. Clin Otolaryngol 1999; 24: 537541.

2.

Weiss NS. Relation of high blood pressure to headache,

epistaxis, and selected other symptoms The United States

Health Examination Survey of Adults. N Engl J Med 1972; 287:

631633.

3.

Massick D, Tobin EJ. Epistaxis. In: Cummings C, Haughey

B, Thomas R, Harker L, Robbins T, Schuller D, Flint P,

editors. Cummings Otolaryngology: Head and Neck Surgery.

Philadelphia, PA, USA: Mosby; 2005. pp. 942961.

4. Pope LE, Hobbs CG. Epistaxis: an update on current

management. Postgrad Med J 2005; 81: 309314.

14. Lubianca Neto JF, Fuchs FD, Facco SR, Gus M, Fasolo L,

Mafessoni R, Gleissner AL. Is epistaxis evidence of end-organ

damage in patients with hypertension? Laryngoscope 1999; 109:

11111115.

15. Alvi A, Joyner-Triplett N. Acute epistaxis: how to spot the source

and the flow. Postgrad Med 1996; 99: 8396.

16. Thaha MA, Nilssen EL, Holland S, Love G, White PS. Routine

coagulation screening in the management of emergency

admission for epistaxis-is it necessary? J Laryngol Otol 2000;

114: 3840.

17. Awan MS, Iqbal M, Imam SZ. Epistaxis: when are coagulation

studies justified? Emerg Med J 2008; 25: 156157.

5.

Shaw CB, Wax MK, Wetmore SJ. Epistaxis: a comparison of

treatment. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1993; 109: 6065.

18. Hanif J, Tasca RA, Frosh A, Ghufoor K, Stirling R. Silver nitrate:

histological effects of cautery on epithelial surfaces with varying

contact times. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci 2003; 28: 368370.

6.

Monte ED, Belmont MJ, Wax MK. Management paradigms for

posterior epistaxis: a comparison of costs and complications.

Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1999; 121: 103106.

19. Mathiasen RA, Cruz R. Prospective, randomized, controlled

clinical trial of a novel matrix hemostatic sealant in patients with

acute anterior epistaxis. Laryngoscope 2005; 115: 899902.

7.

Gifford TO, Orlandi RR. Epistaxis. Otolaryngol Clin N Am

2008; 41: 525536.

8.

Gen S, Krkolu S, Karabulut H, Acar B, Tunel , Deerli

S. Giant lobular capillary hemangioma of the nasal septum.

Turk J Med Sci 2009; 39: 325328.

20. Klotz DA, Winkle MR, Richmon JBS, Hengerer AS. Surgical

management of posterior epistaxis: a changing paradigm.

Laryngoscope 2002; 112: 15771582.

9.

El-Guindy A. Endoscopic transseptal sphenopalatine artery

ligation for intractable posterior epistaxis. Ann Otol Rhinol

Laryngol 1998; 107: 10331037.

10. Middleton MP. Epistaxis. Emergency Medicine Australasia

2004; 16: 428440.

11. Santos PM, Lepore ML. Epistaxis. In: Bailey BJ, Calhoun KH,

Derkay CS, Friedman N, Gluckman J, Healy GB, Jackler RK,

Johnson JT, Lambert PR, Newlands S et al., editors. Baileys

Head and Neck Surgery-Otolaryngology. Philadelphia, PA,

USA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2001. pp. 513529.

12. Herkner H, Havel C, Mllner M, Gamper G, Bur A, Temmel AF,

Laggner AN, Hirschl MM. Active epistaxis at ED presentation

is associated with arterial hypertension. Am J Emerg Med

2002; 20: 9295.

13. Herkner H, Laggner AN, Mllner M, Formanek M, Bur A,

Gamper G, Woisetschlger C, Hirschl MM. Hypertension in

patients presenting with epistaxis. Ann Emerg Med 2000; 35:

126130.

136

21. Kurtaran H, Ark N, Sadkolu F, Uur K, Ylmaz T, Yldrm Z,

Akta D. The effect of anterior nasal packing with airway tubes

on pulmonary function following septoplasty. Turk J Med Sci

2009; 39: 537540.

22. Bhatnagar RK, Berry S. Selective surgicel packing for the

treatment of posterior epistaxis. Ear Nose Throat J 2004; 83:

633634.

23. Thornton MA, Mahesh BN, Lang J. Posterior epistaxis:

identification of common bleeding sites. Laryngoscope 2005;

115: 588590.

24. Shaheen OH. Arterial epistaxis. J Laryngol Otol 1975; 89: 1734.

25. Sokoloff J, Wickborn I, McDonald D, Brahme F, Goergen TG,

Goldberger LE. Therapeutic percutaneous embolization in

intractable epistaxis. Radiology 1974; 111: 285287.

26. Smith TP. Embolization in the external carotid artery. J Vasc

Interv Radiol 2006; 17: 18971912.

27. Kumar S, Shetty A, Rockey J, Nilssen E. Contemporary surgical

treatment of epistaxis. What is the evidence for sphenopalatine

artery ligation? Clin Otol 2003; 28: 360363.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5795)

- Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Treating Meibomian Gland Dysfunction With AzithromycinDocumento12 pagineSystematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Treating Meibomian Gland Dysfunction With AzithromycinStephanus AnggaraNessuna valutazione finora

- HOA With AgeingDocumento5 pagineHOA With AgeingStephanus AnggaraNessuna valutazione finora

- Daftar Pustaka: Universitas Sumatera UtaraDocumento4 pagineDaftar Pustaka: Universitas Sumatera UtaraStephanus AnggaraNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Referat Persentation: Trauma Tumpul AbdomenDocumento1 paginaCase Referat Persentation: Trauma Tumpul AbdomenStephanus AnggaraNessuna valutazione finora

- Pi Is 1933171112003002Documento10 paginePi Is 1933171112003002Stephanus AnggaraNessuna valutazione finora

- Rhyming WordslDocumento1 paginaRhyming WordslStephanus AnggaraNessuna valutazione finora

- FT MaterialDocumento1 paginaFT MaterialStephanus AnggaraNessuna valutazione finora

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Tips To Diagnose & Address Common Horse AilmentsDocumento6 pagineTips To Diagnose & Address Common Horse AilmentsMark GebhardNessuna valutazione finora

- CHDC8 Cargador de BateriasDocumento1 paginaCHDC8 Cargador de Bateriasleoscalor6356Nessuna valutazione finora

- Reticular AbscessDocumento4 pagineReticular AbscessSasikala KaliapanNessuna valutazione finora

- XII Biology Practicals 2020-21 Without ReadingDocumento32 pagineXII Biology Practicals 2020-21 Without ReadingStylish HeroNessuna valutazione finora

- Ear CandlingDocumento2 pagineEar CandlingpowerleaderNessuna valutazione finora

- 19.-Solid Waste TreatmentDocumento108 pagine19.-Solid Waste TreatmentShaira Dale100% (1)

- Decompensated Congestive Cardiac Failure Secondary To No1Documento4 pagineDecompensated Congestive Cardiac Failure Secondary To No1Qi YingNessuna valutazione finora

- Foundations of Group BehaviorDocumento31 pagineFoundations of Group BehaviorRaunakNessuna valutazione finora

- Abrams Clinical Drug Therapy Rationales For Nursing Practice 11th Edition Test BankDocumento6 pagineAbrams Clinical Drug Therapy Rationales For Nursing Practice 11th Edition Test BankWilliam Nakken100% (28)

- Pulse Oximetry CircuitDocumento19 paginePulse Oximetry Circuitنواف الجهنيNessuna valutazione finora

- PCC 2 What Is PCC 2 and Article of Leak Box On Stream RepairGregDocumento12 paginePCC 2 What Is PCC 2 and Article of Leak Box On Stream RepairGregArif Nur AzizNessuna valutazione finora

- Applications Shaft SealDocumento23 pagineApplications Shaft SealMandisa Sinenhlanhla NduliNessuna valutazione finora

- Aqa Food Technology Coursework Mark SchemeDocumento7 pagineAqa Food Technology Coursework Mark Schemeafjwdbaekycbaa100% (2)

- HSE TBT Schedule - Apr 2022Documento1 paginaHSE TBT Schedule - Apr 2022deepak bhagatNessuna valutazione finora

- Trombly - Pump Status PDFDocumento8 pagineTrombly - Pump Status PDFilhamNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson 2.1 Earth As The Only Habitable PlanetDocumento37 pagineLesson 2.1 Earth As The Only Habitable Planetrosie sialanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Antibacterial Effects of Essential OilsDocumento5 pagineAntibacterial Effects of Essential Oilsnightshade.lorna100% (1)

- Von Willebrand Disease in WomenDocumento0 pagineVon Willebrand Disease in WomenMarios SkarmoutsosNessuna valutazione finora

- Cat 4401 UkDocumento198 pagineCat 4401 UkJuan Ignacio Sanchez DiazNessuna valutazione finora

- Motivational Interviewing (MI) Refers To ADocumento5 pagineMotivational Interviewing (MI) Refers To AJefri JohanesNessuna valutazione finora

- Structural Tanks and ComponentsDocumento19 pagineStructural Tanks and ComponentsRodolfo Olate G.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Science Grade 7: Active Reading Note-Taking GuideDocumento140 pagineScience Grade 7: Active Reading Note-Taking Guideurker100% (1)

- Medical Imaging WebquestDocumento8 pagineMedical Imaging Webquestapi-262193618Nessuna valutazione finora

- Cupping TherapyDocumento6 pagineCupping TherapymsbunnileeNessuna valutazione finora

- Q1 GRADE 10 SYNCHRONOUS REVISED Fitness-Test-Score-CardDocumento1 paginaQ1 GRADE 10 SYNCHRONOUS REVISED Fitness-Test-Score-CardAlbert Ian CasugaNessuna valutazione finora

- Gene SileningDocumento30 pagineGene SileningSajjad AhmadNessuna valutazione finora

- Daily Lesson Log Personal Dev TDocumento34 pagineDaily Lesson Log Personal Dev TRicky Canico ArotNessuna valutazione finora

- Module 3 Passive Heating 8.3.18Documento63 pagineModule 3 Passive Heating 8.3.18Aman KashyapNessuna valutazione finora

- KQ2H M1 InchDocumento5 pagineKQ2H M1 Inch林林爸爸Nessuna valutazione finora

- Security Officer Part Time in Orange County CA Resume Robert TalleyDocumento2 pagineSecurity Officer Part Time in Orange County CA Resume Robert TalleyRobertTalleyNessuna valutazione finora