Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Why Wish Away Glagolitic - William Veder

Caricato da

Basil ChulevCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Why Wish Away Glagolitic - William Veder

Caricato da

Basil ChulevCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Ricerche slavistiche 12 (58) 2014: 373-385

WILLIAM R. VEDER

WHY WISH AWAY GLAGOLITIC?

Malum nascens facile opprimitur,

inveteratum fit plerumque robustius

Ovidius

Scholarship guided by wishful thinking cannot yield reliable results.

Take the assumption in Slavic studies that Slavonic was a language

of the people and, consequently, subject to chronological and topological change: it wilfully ignores the fact that the language was destined to express Gods Word, which will not pass away (Mt 24:35).

Let me present two examples of such wishful thinking, one of which

has stunted the study of Slavonic for almost eighty years.

Wishing a Synod at Preslav in 893/4

Regino of Prm ( 915) in his Chronicon inserted sub anno 868 a

notice on Bulgarian affairs, which mentions the baptism of the people (864) and goes on to say that the king deinde, convocato omni

regno suo, filium iuniorem regem constituit1 afterwards, having convened all his realm, he appointed his younger son king (evidently

not in 868, but we are left to guess when).

Patriarch Nikephoros I ( 828) in his Chronographikon does not

mention this event, but the anonymous continuation (only partially

known in Greek) states sub anno 893/4 that from the baptism of the

Bulgarians to the !"#$%&'()* +,()-, [it is] 30 years, and from the

(1) F. Kurze (ed.), Reginensis abbatis Prumiensis Chronicon. Hannover 1890, p.

95 (= Scriptores rerum germanicarum, 50). On Regino, see W. Hartmann in Neue

Deutsche Biographie, 21 (2003), pp. 269-270.

374

William R. Veder

Seventh Council to the !"#$%&'()* +,()-, 77 years, and from Adam

6405 or 6.2 There is an event, but we are left to guess which.

In 1925, Vasil Zlatarski had no doubt that the dates could be

equated and the events related. He saw !"#$%&'()* +,()-, as the

first official act of the new prince in his new capital city, Preslav

(which may have been no more than a construction site by 894), and

interpreted the Slavonic to refer to either transfer or replacement,

and to Scripture, books, and the collocation to mean either translation of Scripture (i.c. scriptural commentaries) or replacement of

books (i.c. Greek by Slavonic for divine service).3

Out of convocato omni regno suo + !"#$%&'()* +,()-, + 6405

or 6 by sheer wishful thinking was born an event: The Synod of

Preslav of 893/4. German historians would call such arbitrary conflation Geschichtsklitterung making a hotchpotch of history.

Wishing the Synod to Take Action

Six years later, Grigorij A. Ilinskij wholeheartedly embraced Zlatarskijs conflation, taking issue only with his interpretation of the

collocation !"#$%&'()* +,()-,. He pointed out that +,()-. can refer

not only to book or books, but also to letters, and proposed to

read !"#$%&'()* +,()-, as replacement of letters and to refer to the

replacement of the Glagolitic alphabet by the Cyrillic. He even supplied an author of the new letters, Constantine the Younger of Preslav (Zlatarski had simply asked whether a name might have been

omitted after +,()-,), as well as a reason for the replacement: the

(2) On patriarch Nikephoros I, see Alexander P. Ka!dan in Oxford Dictionary of

Byzantium. New York - Oxford 1991, p. 1477; on the Chronographikon and its Slavonic translation, see Elena K. Piotrovskaja in Slovar kni!nikov i kni!nosti Drevnej

Rusi, t. 1. Leningrad 1987, pp. 231-234; for more recent editions of the translation,

see Dmitrij M. Bulanin, Katalog pamjatnikov drevnerusskoj pismennosti XI-XIV vv.

(Rukopisnye knigi). S. - Pb. 2014, p. 360; for misreadings of numerals in the Glagolitic translation (like the 5 or 6 shown), see Maria Spasova, K"m v"prosa za slavjanskija prevod na L#topis$c$ v% krat$c# na patriarx &ikifor, Die slawischen Sprachen, 33 (1993), pp. 81-91.

(3) V. Zlatarski, Stranica iz starata kulturna istorija na b"lgarite, in Sbornik v

'est i v pamet na Lui Le!e. Sofia 1925, pp. 279-302, repr. in Istorija na b"lgarskata

d"r!ava, t. 1, ". 2. Sofia 1927, repr. Sofia 1971.

Why Wish Away Glagolitic?

375

behest of the new prince, who strove to facilitate and speed the process of slavicisation of the Bulgarian church and state.4

The Synod of Preslav of 893/4 had now been wishfully supplied with an agenda and at least one of its executors. More importantly, Slavonic studies had been streamlined, the cumbersome Glagolitic writing confined to the initial fourty years of literacy. All of

this appealed to the common sense of the community of slavists:

many of the articles in the Kirilo-Metodievska enciklopedija (Sofia

1985-2003) show its pervasiveness.5

This is wishful thinking on a grand scale: Ilinskij, in fact, postulated a model of text production and transmission without having any

relevant study to rely on.6 Like his teachers over the previous century and a half, he assumed that, Slavonic being a language of the

people, every scribe was free to write how he wanted, i.e. that text

production and transmission in Slavonic did not differ from that in

Western European vernaculars.7 He even ignored Mixail N. Speranskijs paper of three years earlier on the Glagolitic ancestry of the Evgenievskaja and Tolstovskaja Psalters (11th c.) and other early Novgorod manuscripts.8 So he could not know that, while !"#$%& can in(4) G. A. Ilinskij, Gde, kogda, kem i s kakoju celju glagolica byla zamenena kirillicej, Byzantinoslavica, 3 (1931), pp. 79-88.

(5) It is to the credit of the editors of the Enciklopedija that they avoided devoting an entry to the Synod of Preslav.

(6) The first pertinent study belongs to Josif Popovski. Najstariji par antigrafa i

apografa u slovenskoj pismenosti, destined to be published in Palographie et diplomatique slaves, 3 (1987), but vanished with its archive in Sofia (Viktor M. !ivov, Vosto!noslavjanskoe pravopisanie XI-XIII veka. Moskva 2006, pp. 9-75, perused a manuscript copy); it will be published in Polata knigopisnaja, 41 (2015).

(7) The idea that scribes must have written in their own tongue was first expressed by Mixail M. "#erbatov, Istorija rosskijskaja ot drevnej"ix vremen, 1. S. - Pb.

1770, p. iv, in reference to his Izbornik of 1076; it was given semblance of fact by

the work of Nicolaas van Wijk, who could rely on extensive experience in MiddleDutch text transmission (see my Kirchenslavische Handschriften und Texte im Werk

#icolaas van Wijks, in W. R. Veder, Hiljada godini kato edin den. Sofia 2005, pp.

59-62).

(8) M. N. Speranskij, Otkuda idut starej"ie pamjatniki russkoj pismennosti i literatury?, Slavi$, 7 (1927-28), pp. 516-535; the paper is also ignored in the edition

of Viktor V. Kolesov, Evgenievskaja Psaltyr, Dissertationes Slavicae, 8 (1972),

pp. 58-69 + 40 pp. facsimile.

376

William R. Veder

deed refer to letters (as can !"#$%&# writ, writing, "'() speech

and *+%,% word), it invariably does so in replacing -.*$/0#.9 And he

could not know that Constantine the Younger of Preslav did not produce texts written in Cyrillic.10 Finally, he could not know that the use

of Glagolitic in text production can be traced up to the 12th c. and in

text transmission well into the 17th c.

Glagolitic Features in Text Transmission

Manuscript transmission of texts, like any data processing, is an interface of three components: 1 input ! 2 processing ! 3 output, 3

being the copy, 2 the copyist, or more precisely his language and text

competence, and 1 the antigraph which provides the data for the output. Processing and output are largely determined by the features of

the input:11 if copies from different regions and different times show

the same pattern in their variation, its source should be sought in 1,

not in 2.12 Cyrillic antigraphs yield variation patterns different from

Glagolitic antigraphs.13 The eight components of the latter variation

pattern will be summarily reviewed below.

1 The presence of Glagolitic writing in a copy, be it entire lines

(e.g. 1*2345#| 6789:;< =:>:?<@A Bitolja Triodium Sofia BAN 38,

(9) See e.g. my Variacija v krugu semi O Pismenex!, in Milena Dobreva (ed.),

Text Variety in the Witnesses of Medieval Texts. Sofia 1997, pp. 110-125. A rare text,

in which "#$%&% is translated by !"#$%&# and both "#$% and '&()*+,(- by *+%,%

and -.*$B, is a scholion in the Chronograph, see my Ot edin prevod do O Pismenex

i do Hronografa, Preslavska kni.ovna /kola, 13 (2012), pp. 185-202.

(10) See Georgi Popov, Triodni proizvedenija na Konstantin Preslavski. Sofia

1985 (= Kirilo-Metodievski studii, 2) and his additional editions in Palaeobulgarica, 19 (1995) 3, pp. 3-31, 21 (1997) 4, pp. 3-17, 22 (1998) 4, pp. 3-26; see also my

Utrum in alterum abiturum erat?. Bloomington 1999, pp. 58, 61-87.

(11) Suffice it to recall the principle of data processing Garbage in garbage out.

(12) It would be preposterous to claim that thousands of copyists had the same tics

nerveux.

(13) In the transmission of the Scete Paterikon, the witnesses of text family c depend from a 10th c. Cyrillic antigraph. Their variation can be compared to that of

the other text families (which all depend from Glagolitic antigraphs) in my The Collation of the Witnesses to the Scete Patericon, Polata knigopisnaja, 37 (2006); see

also my One Translation Many Transcriptions, in W. R. Veder, Hiljada godini,

cit., pp. 229-243.

377

Why Wish Away Glagolitic?

f. 43), incidental letters (e.g. !"#$%&%'( )( "*+,)$-. Scala Paradisi

Moscow RGB F.304 nr. 161, f. 26v, from f. 33v on ! more frequently) or single signs (e.g. /0+, # '*1,2"3'456, Izmaragd Moscow

RGB F.304 nr. 203, f. 147v), constitutes proof of its direct contact

with Glagolitic.14

2 Numerical values of Glagolitic and Cyrillic letters are not equal:

1

7

*

9 : ; <

2 G + %

10

= > ? @

H I #

6

20 30 40 50 60 70

J

9

K

10

B C

D E 6

L 1 ' 5

80

20 30 40 50 60 70

Typical variant readings are: <@N ! %KN (transliteration) : HKN (transcription) : IKN (mistranscription) : O# (misinterpretation). They have the

same value of proof as Glagolitic writing.

3 Markers for jotation and palatality were lacking in the original

Glagolitic alphabet15 and had to be added in the Cyrillic copy (P for

jotation of vowels and palatality of preceding consonants, ( for nonpalatality of consonants):

a 7 ! */Q

e < ! %/O u R ! 0/. ! S ! T/( " U ! V/W

# X ! 4/Y

Typical variant readings are: 79Z ! *23 (transliteration) : Q23 (transcription) : 323 (transcription); ;77[@ ! +**$# (transliteration) :

+*Q$# (transcription) : +3*$# (mistranscription); 6<R=< ! 5% 0\%

(transliteration) : 5%.\% (transcription); ]SDF=@ 9S 6S ! )T1,\# 2T

5T (transliteration) : )(1,\# 2( 5T (transcription + transliteration) :

)(1,\#2(^ 5( (mistranscription).

4 Nasal vowels were an endangered species as early as the 10th c.

(see e.g. Mt 19:9 $2,"#$( W [! 4 Vat] _"31.`a $2,"#$#, Jn 21:6

2"Tb3$% 5* +%)5VW c4)$T L,"*`1Q '"3\V [! '"3\4 Zog Ass] #

,`"4d%-$%^ 2"TGV \%^ # L( $,'0 OY _"#213d# 5% ',\**eV), and their

(14) For a comprehensive survey, see Javor Miltenov, Kirilski r$kopisi s glagoli%eski vpisvanija, Wiener slavistisches Jahrbuch, 55 (2009), pp. 191-219, 56 (2010),

pp. 83-98.

(15) Original Glagolitic is reflected only in direct copies in Cyrillic (see my The

Glagolitic Barrier, Studies in Slavic and General Linguistics, 34 (2008), pp. 489501). Attested Glagolitic borrowed from Cyrillic the doubling of the last four vowel

signs (u f/g, ! S/h, " i/j, # X/k), see e.g. the splendidly documented edition of

Heinz Miklas et al. (eds.), Psalterium Demetrii Sinaitici, Bd. 1. Wien 2012, pp. 87111, 129-131.

378

William R. Veder

confusion has nothing to do with regional variety,16 nor is it limited

to the nasal vowels themselves (see e.g. Lk 24:22 !"#$ %&"'$ (&)

#*+) ,!*+-./ [! ,!*+-." Zog] #$). Typical variant readings are:

01-2317 ! 45&- (transliteration) : 4/&- (mistransliteration, see also

the hybrid 46&-) : 4,&- (transcription) : 4)7-&- (transcription with

m from internal dictation); 389:; ! -7)." (transliteration + transcription) : /." (mistranscription with im telescoped by internal dictation); <=>?:? ! #*@/./ (transliteration) : #*@*.* (transcription) :

#*@/.5 (transliteration + mistranscription) : #*@A#)." (mistranscription with n from internal dictation) : #*@A#)."7) (mistranscription

with n and m from internal dictation).

5 Confusion of consonants is rife in copies from Glagolitic antigraphs.18 Most frequent are the following types: (a) B " C e.g. (D*@" :

- E*@", E'F7F#- : D'F7"#-; (b) G " 0 " H " 2 e.g. +)I)J* : +)IA4*,

I)J*J) : I)J*K), E(L#"&"#) : E(L#"J"#), 4FK( : KF&(: &FK(; (c) M " N "

O (Greek #19) e.g. L+* : P+*, P'-+&-Q#) : R'A+&-Q#), E(R,4-&- : E(P,K-&-; (d) 8 " S (Slavic !19) e.g. 7(K-&- : PJ*K-&-, -7FP) : -7*7A;

(e) T " > $ E(+FU"#-% : E(+F@"#-%, E(+F@"#) : E(+FU"#). Here, too,

belong three Cyrillic graphs V, W and X not included in original Glagolitic: Y;Z=[\89 ! +"'*]-7) (transliteration) : +"'*V-7) (transcription); =H;NY=<0Z^ ! *K"R+*#4'A (transliteration) : *K"W*#4') (transcription), CY=H8^ ! E+*K)7) (transliteration with epenthesis of )) :

X+K7) (transcription with retention of Glagolitic s) : X*K7) (transcription).

6 Of the Glagolitic vowel signs (a) four are predisposed to confusion by their very form, viz. e ; " o _ " u ` " " 9: e.g. E'"IJa&"') :

(16) See my East-Slavic Confusion of #asals, Pegasus Oost Europese Studies,

20 (2012), pp. 639-648.

(17) The monograph 1 is attested in Miklas, Psalterium, cit., p. 88 (hand A for

^) and 102 (hand C as variant of ^).

(18) Three of these confusions have unilaterally been ascribed linguistic relevance: 7 b P (in desinences: replacement of possessive Dative plural ! Genitive), P'

! R' and U ! @ (East Slavic dialectisms), but this is an arbitrary interpretation,

since the confusions are bilateral.

(19) Cyrillic copies reflect the functional distinction of the two x-graphs, lost in

attested Glagolitic: in Greek stems x alternates with g k and sometimes r, which

means it was written O (see M : N : Z), in Slavic stems and desinences with m and sometimes v n t, which means it was written S (see 8 : G : < : 2).

Why Wish Away Glagolitic?

379

!"#$%&'("), !"#*+),(-) : !"(*+#,(-), -( : -# : -), ./-#-) : ./-0-),

12340 : 1234), 5( %6*#2# : 5)%6*#2). (b) They are joined by a,

which can be written similar to e:20 e.g. 7,( : 8,(, / 23,/ : 820,(.

(c) Further a 9, y : and ! ; have features, which allow them to be

confused: e.g. 2<$*/ : 2<$*=, -=-6 : -6-7, >=?@ : >6?@. (d) The

letter " A does not only alternate with ), in tense position it alternates with 1 and =: e.g. BACDAEAF : 52"G'H : 52"G'<1 (transliterations)

: 5)2"<'11 (transcription), IJKAF ! -#%H : -#%<1 (transliteration) : -#%=1 (transcription). (e) Finally, L (Greek #) is variously rendered as

1, 0/M or &: e.g. BELNO9 ! 5'1P17 : 5'0P17 : 5'MP17 (transcriptions) : 5'&PQ/ (transliteration).

7 Epenthesis of vowels or consonants in order to adapt clusters to

Slavonic phonotactics or to mark palatality of labials is lacking in

Glagolitic and has to be added in Cyrillic. Typical variant readings

are: (jer) 9RSTB9IUDA ! /+(V/-*") : /+(.5/-)*") : /+(.5/-*)"), OW9IIA ! XY/--) : XY/-Z-), [B9RCA ! !5/+2) : !)5/+)2); (consonants)

D9\D;]F ! "/$"6?1 : "/$*"6?1, UDA\I^R ! *"<$-3+) : *")$*-_+),

[JU9EFKA ! !#*/'1%) : !#*/'+1%); (l after palatal labials) `FKab9

! ,1%34/ : ,1%+7c4/, \SCF ! $(21 : $(2+1, [DFC^EA !

!"1123') : !"182+c'), 9KA ! 7%1 : 7%+<.

8 Anagrams, haplograms and tautograms in copies from Glagolitic

are markedly more frequent than in copies from Cyrillic, because decoding morpheme by morpheme (if not letter by letter) prevents

verification of meaning. Typical variant readings are: (anagrams)

`SI^ ! ,(-3 : -0,3, SRF BS ! 8+1 5( : 5(+1, `d^EA ! ,0c') :

,1'1M; (haplograms) KA KL\9IEO^ ! %) %1$/-'1M : %&$/-<'1M, I9

\9[9UA ! -/ $/!/*) : -/ $/*), [D;UA[JRJ`FEF ! !"6*)!#+#,1'1

: !"6*)+#,1'1; (tautograms) 9TJ ! 7.# : 7.#.# and 77.#, SUFIJ !

8*1-# : 8*1-#e#, EKJDabdSCd ! '%#"@4( 820 : '%#"@4(20 820.

Features 1 and 2 are independent; 3-8 need to occur in combination in order to furnish proof of dependence from Glagolitic. If 2-8

occur independently in the copies, they are made directly from Glagolitic; if they occur in the same places, it is their antigraph which

was copied from Glagolitic.21

(20) See Miklas, Psalterium, cit., pp. 97, 101, 109.

(21) This is the case in text family c of the Scete Paterikon (note 13 above), see

380

William R. Veder

Production of Glagolitic Texts up to the 12th Century

Below I list in chronological order datable texts or versions, the transmission of which exhibits features 2-8:

898-899

antigraph of the Clozianus and the homiliary part of the

Suprasliensis;22

before 900 revision of the Scala Paradisi and the Quaestiones ad

Antiochum;23

before 927 protograph of the Izbornik of 1073;24

before 930 protograph of the Scaliger Patericon;25

ca. 930

protograph of the Knja!ij Izbornik;26

before 935 protograph of O Pismenex;27

ca. 960

protograph of the Izbornik of John the Sinner;26

after 992

protograph of the Synaxarium and its enhancement to

the Prolog;28

996

first update of the Chronograph;29

after 1097 protograph of the Dioptra of Philippos Monotropos.30

my Der glagolitische Archetyp des Paterik Skitskij, in Dutch Contributions to the

Eighth International Congress of Slavists. Lisse 1979, pp. 339-346.

(22) See M. Spasova, W. R. Veder, Copying, Copy-Editing, Editing and Recollating Three Chrysostomian Lenten Homilies in Slavonic, Polata knigopisnaja, 38

(2010), pp. 97-144; Bulgarian: Prepisvane, popravjane, redaktirane i sverka na slavjanskija prevod na tri Zlatoustovi velikopostni slova, Preslavska kni!ovna "kola,

9 (2006), pp. 53-107.

(23) See my Psevdo-Atanasij Aleksandrijski. V"prosi i otgovori k"m knjaz Antioh, tt. 1-2. Veliko T#rnovo, forthcoming.

(24) See my Preslu#vajki edna poxvala, in M. Jov$eva et al. (eds.), P$nie malo

Georgiju. Sbornik v %est na 65-godi#ninata na prof. dfn Georgi Popov. Sofia 2010,

pp. 358-366.

(25) See my Der Stein, den die Bauleute verworfen haben, Die Welt der Slaven, 57 (2012) 2, pp. 293-305.

(26) See my Knja!ij Izbornik za v"zpitanie na kanartikina, tt. 1-2. Veliko T#rnovo 2008.

(27) See my Utrum in alterum, cit., pp. 58, 88-152.

(28) See my Markup in the Prolog, Polata knigopisnaja, 39, forthcoming.

(29) See my Ot edin prevod, cit.

(30) See the splendidly documented edition Heinz Miklas, Jrgen Fuchsbauer, Die

kirchenslavische bersetzung der Dioptra des Pilippos Monotropos, Bd. 1. Wien

Why Wish Away Glagolitic?

381

To these should most probably be added the protograph of the Catecheses of Symeon the New Theologian ( 1022). The copy of the

Glagolitic Scala Paradisi Moscow RGB F.304 nr. 161, f. 6-8v, inter2013. It attests the following variants (small numbers refer to pages): 1 Glagolitic

339 !"#. 3 Confusion of nasals is ubiquitous (esp. in L), incl. confusion with oral

vowels, e.g. 331 $%&'()*+, ! $&'()*-, (# ! .), 341 */*0!$12 ! /*0!$13, (. !

#), 351 45,6,% ! 4573,8 (9 ! #). 4 Confusion in jotation is ubiquitous in hiatus; in

addition e.g. 331 *)8$:&5;5 ! )%$*&5;5, 339 &'*$6733 ! &'6$6733, 345 $<=>6 !

$<=*, 353 )*'67!4% ! )6'67!4, ?-@51&5'/(! ! 1@A 1&5'!B/(, 373 0'- ! 0'1,

385 *!$&'8/:C;5 ! !$&'8/D/**;5. 5 Consonants: (E ! F) 353 *,GH0*/! ! ,1H@*/!

: ,>H@*/!; (I ! J) 351 */5;%,!! ! /5&,!! : /5&,3!, 377 A0?%)*$,3 ! A@?%)*$,3, 395

A,6;K3/L ! A@,6&K3/1; (M ! N) 339 O,<=1 ! O,5?P; (M " Q) 355 *=P:/!:

! ,PKC/>*, **/,5/!! ! */=5/>3, 373 *;5$05=8$,)R ! ;$,)( L; (S) 353 1$?*"=3/>*

! 1$?*"*/>*, 355 /<"=< ! /1"*, 367 '5"=%$,)5 ! '5=8$,)5; (N " T) 337 !/5 !

!?!, 353 0!7*?3H% ! 0!7*/3H; (T ! U) 379 A/*H5 ! A)*H5; (F ! Q) 397 0?5=5H8

! ,'V=5H; (Q ! M) 351 !$,%7!)W! ! !"=!)W!; (Q ! X) 329 /*'!Y*3, ! /*'!Y*3H%; (X " Z) 331 )%B($&*<7!H ! )%B($&*-7!4, 333 )'PH3/34 ! )'PH3/3H8, 359

/*$!?1+H(!H% ! /*$!?V3H(4%, A@!=!HRH% ! 5@!=!H(4, )%$PH% 0'*)3=/(H% !

)8$P4 0'305=@/>!4, 369 )%$PK%$&RH% ! )$6K8$&(4, 371 /@$/(H! ! /@$/>!4, 399 @?[;!H% ! @?[;(4, 400 )P7*-7!4% ! )P7*-73H, 401 0'!,P&*-7!4 ! 0'!,P&*-7!H, )$3H

! )D$P4%; (Q ! \) 359 **/,5/!! ! */D]A/>+; (^ ! I) 359 *='64?12,% ! ='6;?V-,. 6 Vowels: widely confused (L is heavy in % by surfeit of transcription); linguistic explanation fails in (_ " #) 343 :"3 ! 3"3, 347 '(=*/>* ! '!=*/>3, 335 =W[3

! =W[*, 353 *14R7'3/!C ! 14(7'3/>*, 1;5=!* ! 1;5=>3, 1$?*"=3/>* ! 1$?*"*/>*, 355 105&53/>* ! 105&5:/8: : 105&53/>+, 361 =W[3 ! =W[*, 365 K'%)>* !

K'8)>3, 367 )%/ 6"3 ! )% C"3, 371 0'P,)5'3/>3 ! 0'3,)5'3/>:, 375 '*B?<K3/!3 ! '*B?LK3/>*, 377 )%$3?-@!H* ! )%$:?-@!H*, 389 &'*$5)*/>3 ! &'*$5)*/>*, 391 )%B=(4*/!* ! )%BD=(4*/>3, 394 /*0*=3/>* ! /*0*=*/!:, 398 0'5W3/8+ ! 0'5W3/>6,

400 $@3$P=5)*/8+ ! B@3$P=5)*/8:, 401 0'5K3C ! 0'5K*6, ?!Y3 ! ?!Y*; (# " ` " a

" .) 349 ='1;5+ ! ='5;5+, 351 ,)5'Y1 ! ,D)L'YL, 355 )%$4(73/!- ! )%$4!73/>+, 355 @?!B% ! @?!B1, 357 !7<73 ! !7573, 363 '*=5)*/>3 ! '*=5)*/D/5, 377

A$,<0D/!Y! ! O$,50D/!Y!, 385 ,30?P ! ,50?P, 385 *0'5$?8B! ! 0'5$?%B! : 0'5$?3B!,

394 $3 ! $8!, 395 A,6;K3/L ! A@,6;K3/5, 397 /5 ! /3; (# " b " 9) 343 $,!4A)3

! $,>45)%, $,!45)8, 353 *B%?5K6$,8/P ! B?5K3$,/P : B?5K%$,/P, 359 0'P=$,*,3?3 !

0'P=$,*,3?8 : 0'P=$,*,3?6, 367 K6$,! ! K3$,! : K8$,!, 401 @'*,3 ! @'*,%; (a " b)

333 &5/YL ! &5/DY8, 351 $%B=*,3?- ! $5B=*,3?%, 377 A0?%)*$,3 ! A0?-)*$,3, 399

*@1'2 ! @5'-; (c " d) 333 $)P,?P ! $)P,?(; (c ! 6) 355 @5?PB/! ! @56B/!; (e)

353 *,GH0*/! ! ,VH0*/! : ,1H0*/! : ,>H0*/! : ,!HD0/!; (. ! b) 341 *H<='8$,)1273 ! H%='8$,)1-73. 7 Epenthesis: 337 =>A0,'* ! =!f0*,D'*, 355 1:B)P*4< ! 1:BD)?:41. 8 Anagrams: 351 )%$05H!/**4< ! )8$05H3/14, 359 ,PH%

! ,DHP, 361 !$0(,*-,8 ! !$0(,16,D, 401 0'6=3/!: ! 0'3=*/g:. Tautogram: 351

-/(6 ! -/8/(3.

382

William R. Veder

rupts the Epistle of John of Raithou to insert 2 ff. of a catechesis of

Symeon, which the copyist could not recognise as a foreign text because it must have been written in Glagolitic as well.

Transmission of Glagolitic Texts into the 17th Century

Below I list in chronologial order texts, the copies of which individually show the features 2-8:

before 1050 the Pandect of Antioch;31

before 1100 the codex Suprasliensis;32

1175-1450 9 copies of the Scala Paradisi version a;33

1175-1500 6 copies of the Quaestiones ad Antiochum;34

1200-1394 8 South Slavic copies of the Scete Paterikon;35

1275-1520 3 copies of the Scaliger Patericon;36

1275-1600 25 copies of the Chronicle of George Hamartolos;37

1300-1600 39 copies of the Tale of Aphroditian;38

1348

the Ivan-Aleksandrov Sbornik;39

(31) See the edition by Josif Popovski in Polata knigopisnaja, 23-24 (1989), and

his forms index in Polata knigopisnaja, 30-31 (1999). Part of the Cyrillic copy was

copied ca. 1175-1200 into the Troickij Sbornik !r. 12 (ed. Polata knigopisnaja,

21-22 (1988), see Popovski, !ajstariji par, cit.), but f. 1-64 and 158-202 of that

sbornik are copied from Glagolitic.

(32) See Spasova, Veder, Copying, cit.

(33) See my Ploskaja tradicija tekstov, Palaeobulgarica, 36 (2012) 4, pp. 98109 (codd. Moskva RGB F.256 nr. 198 and 199, F.304 nr. 10). From the same Glagolitic antigraph are copied codd. Moskva RGADA MGAMID 452, GIM Sin. 105,

!ud. 218, Uvar. 865 and S.-Pb. RNB Sof. 1214.

(34) Copied in the Trinity-St Sergius Laura from 4 Glagolitic antigraphs, see my

Der Zweite sdslavische Einfluss aus der Sicht der Textberlieferung, Die Welt der

Slaven, 59 (2014) 1, pp. 95-110.

(35) Copied from the protograph at Ohrid, see my Metodievata zla hiena, Kirilo-Metodievski studii, 17 (2007), pp. 783-798.

(36) Copied from the protograph in Volhynia, see my Der Stein, cit.

(37) See my The Trouble with Middle Bulgarian, Polata knigopisnaja, 40, forthcoming.

(38) See my The Slavonic Tale of Aphroditian, T"rnovska kni#ovna $kola, 9

(2011), pp. 344-358.

(39) See my The Trouble, cit.

Why Wish Away Glagolitic?

1350-1600

1380-1620

1390-1550

1390-1700

1400-1526

1400-1700

1500-1650

1590-1650

before 1653

383

16 copies of the works of Dorotheus of Gaza;40

10 copies of the Scala Paradisi version b;41

5 copies of Esther;42

7 copies of the P!ela;43

6 copies of the Scala Paradisi version c;41

3 copies of the Izmaragd in 164 Chapters;44

8 copies of the Epistle of patriarch Photius;37

3 copies of 4-6 Sborniki;45

ch. 69 of the printed Korm!aja.46

Glagolitic Just Faded Away

The 28 texts and their 149 copies listed above are not numerous

compared to the corpus of ca. 8,000 Slavonic texts preserved in ca.

800,000 manuscript books and fragments of the 10th through 20th

centuries. The study of text transmission, even if aiming at no more

than to identify the direct antigraphs of copies, progresses slowly.

Yet they do offer evidence of a type of text tradition foreign to

the postulated Western European vernacular model: a flat tradition,

(40) Of these, 12 were copied in the Trinity-St Sergius Laura from a single antigraph, see my The Trouble, cit. The 3 known South Slavic copies probably depend

from a different antigraph.

(41) Copied in the Trinity-St Sergius Laura from a single antigraph, see my Ploskaja tradicija, cit.

(42) See my Esthers Glagolitic Ancestry, Ricerche slavistiche, Nuova serie 8

(2010), pp. 213-223.

(43) See my A Retrial for the P!ela, Polata knigopisnaja, 38 (2010), pp. 145154.

(44) See my Psevdo-Atanasij, cit., and Gennadius Slavicus in Srednovekovijat

!ovek i negovijat svjat. Veliko T"rnovo, forthcoming.

(45) See my Meleckij sbornik i istorija drevnebolgarskoj literatury, Palaeobulgarica, 6 (1982) 3, pp. 154-165, and Literature as a Kaleidoscope, in W. R. Veder,

Hiljada godini, cit., pp. 102-109. The readings adduced by Marija S. Mu#inskaja

et al. (eds.), Izbornik 1076 goda. Vtoroe izdanie. Moskva 2009, prove that the Lvovskij Sbornik nr. 134 is not copied from the Meleckij Sbornik, but from its Glagolitic

antigraphs; the same will surely hold true for the Uvarovskij Sbornik nr. 157.

(46) See my Avva Anastasij Sinajski. V"prosi i otgovori, t. 1. Veliko T"rnovo

2011, p. 22.

384

William R. Veder

in which all copies belong to the same, the second generation (with

respect to their antigraph). And they do offer evidence of the full validity of Giorgio Pasqualis recentiores non deteriores in the Slavia

slavonica:47 of the 12 copies of the works of Dorotheus of Gaza and

the 16 copies of the Scala Paradisi versions b and c made in the Trinity-St Sergius Laura, the older usually render the antigraph less reliably than the younger.48 Further, they offer a solution to a problem

brought to the fore by the grand master of Slavonic archaeography,

Anatolij A. Turilov, viz. the near-total lack of pairs of antigraph and

apograph:49 after six or more centuries of wear and tear from multiple copying, the Glagolitic antigraphs just faded away. Finally, they

offer evidence that the language of the texts had little in common

with the language of the people: the choice for antigraphs of great

age and the cumulation of copies of the same texts in the library of

the Trinity-St Sergius Laura suggest that they were made for learning (both of the text and its language), rather than for dissemination.

Is it conceivable that the Prague historian and philologist Josef

Karsek (1868-1916) was right when he claimed that Slavonic was a

theoretical, artificial language?50

(47) The overdue reformulation of the dichotomy Slavia orthodoxa ~ Slavia romana (Riccardo Picchio, Questione della lingua e Slavia cirillomethodiana, in Studi sulla questione della lingua presso gli slavi. Roma 1972) in non-confessional

terms as Slavia slavonica ~ Slavia latina belongs to Sante Graciotti, Le due slavie:

problemi di terminologia e problemi di idee, Ricerche slavistiche, 45-46 (19981999), pp. 5-86.

(48) An exception is the youngest copy of the Izmaragd, which suffers from haste.

(49) He complained that this lack impedes the study of the so-called Second

South Slavic Influence (sse my Der Zweite, cit.) in Russian letters: !"-"# $%&'(

$%)*%+% %',-','.(/ *0%12%3(452 3)/ (,,)03%.#*(/ $#6 %6(+(*#)-7%$(/

6080*(0 .%$6%,# -$(6#0',/ . ,%$%,'#.)0*(0 1%)98%+% &(,)# .%,'%&*%- ( :;*%,)#./*,7(2 ,$(,7%. %3*%+% ( '%+% ;0 '07,'#, A. A. Turilov, Vosto!noslavjanskaja kni"naja kultura konca XIV-XV vv. i vtoroe ju"noslavjanskoe vlijanie, in his

Slavia Cyrillomethodiana: Isto!nikovedenie istorii i kultury ju"nyx slavjan i Drevnej Rusi. Moskva 2010, p. 239. It should be noted that the lack of extant anti-graphs

exceeds the time frame given.

(50) Josef Karsek, Slavische Literaturgeschichte, Bd. 1. Leipzig 1906, p. 13, repr.

on demand Bd. 1-2 by Bibliobazaar: Charleston, SC (via <amazon.com>).

Why Wish Away Glagolitic?

385

!"#$%"

&. '. ()*+,-.+/ 1931 0. ,12314+) ,1 )56,7/ 289* -)14+-9+.8, 894:3;+4, <95

,1 =3:-)14-.5> ?5@53: 893/4 0. 0)105)+A1 @7)1 B1>:,:,1 .+3+))+A:/. C,+>19:)*,5: +B8<:,+: 931,->+--++ 28 -)14D,-.+E 9:.-954 25 149 -2+-.1> 47D4)D:9 1.9+4,5: +-25)*B54,+: 0)105)+<:-.505 2+-*>1 ;5 ,1<1)1 FGG 4., 1 21--+4,5: 42)59* ;5 XVII 4.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- SCHMITZ2008Documento6 pagineSCHMITZ2008simpletheu100% (1)

- Reply of The Zaporozhian CossacksDocumento16 pagineReply of The Zaporozhian CossacksElder FutharkNessuna valutazione finora

- A Lost Byzantine Chronicle in Slavic Translation: Studia Ceranea 1, 2011, P. 191-204Documento8 pagineA Lost Byzantine Chronicle in Slavic Translation: Studia Ceranea 1, 2011, P. 191-204jclamNessuna valutazione finora

- Old Slavonic and Church Slavonic in TEX and Unicode: Alexander Berdnikov, Olga LapkoDocumento32 pagineOld Slavonic and Church Slavonic in TEX and Unicode: Alexander Berdnikov, Olga LapkoEneaGjonajNessuna valutazione finora

- ČeptrDocumento23 pagineČeptrТев ЛевNessuna valutazione finora

- Old Church SlavonicDocumento32 pagineOld Church Slavonicfunmaster100% (1)

- The Georgian Manuscripts of Saint Paul's LettersDocumento5 pagineThe Georgian Manuscripts of Saint Paul's LettersGiorgi SoseliaNessuna valutazione finora

- Srbija I Duklja U Delu Jovana SkiliceDocumento28 pagineSrbija I Duklja U Delu Jovana Skiliceautarijat4829Nessuna valutazione finora

- Slavic Mythology: Folklore & Legends of the SlavsDa EverandSlavic Mythology: Folklore & Legends of the SlavsValutazione: 3 su 5 stelle3/5 (1)

- Evidence For Early Slavic Presence in Minoan CreteDocumento11 pagineEvidence For Early Slavic Presence in Minoan CretethersitesNessuna valutazione finora

- Kazhdan Some Little-Knownor Misinterprete Edvidence PDFDocumento16 pagineKazhdan Some Little-Knownor Misinterprete Edvidence PDFRodica GheorghiuNessuna valutazione finora

- 2007 Chrysos Settlements of SlavsDocumento14 pagine2007 Chrysos Settlements of SlavsIske SabihaNessuna valutazione finora

- GlagolithicDocumento5 pagineGlagolithicsebastian54Nessuna valutazione finora

- C. Davenport and C. Mallan - Dexippus Letter of Decius Context and InterpretationDocumento18 pagineC. Davenport and C. Mallan - Dexippus Letter of Decius Context and InterpretationLorenzo BoragnoNessuna valutazione finora

- The Late Byzantine Army: Arms and Society, 124-1453Da EverandThe Late Byzantine Army: Arms and Society, 124-1453Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (8)

- The noble Polish family Kolodyn. Die adlige polnische Familie Kolodyn.Da EverandThe noble Polish family Kolodyn. Die adlige polnische Familie Kolodyn.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Prisoners of War in Early Medieval BulgaDocumento33 paginePrisoners of War in Early Medieval Bulgastefan stefanosNessuna valutazione finora

- The Forgotten "Kingdom of The Slavs" by Mauro OrbiniDocumento16 pagineThe Forgotten "Kingdom of The Slavs" by Mauro OrbiniTomasz KosińskiNessuna valutazione finora

- The noble Polish family Zienowicz. Die adlige polnische Familie Zienowicz.Da EverandThe noble Polish family Zienowicz. Die adlige polnische Familie Zienowicz.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Symbolism of Some Animals in The Early Medieval SerbiaDocumento12 pagineSymbolism of Some Animals in The Early Medieval Serbiatibor zivkovic100% (2)

- Slavs AdriaticDocumento0 pagineSlavs Adriatict3klaNessuna valutazione finora

- Damir Gazetić - Selected Short Works: Essays, Fiction, PoetryDocumento67 pagineDamir Gazetić - Selected Short Works: Essays, Fiction, PoetryДамир ГазетићNessuna valutazione finora

- Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition, Volume 14, Slice 6 "Inscriptions" to "Ireland, William Henry"Da EverandEncyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition, Volume 14, Slice 6 "Inscriptions" to "Ireland, William Henry"Nessuna valutazione finora

- On The Historicity of Old Church SlavonicDocumento7 pagineOn The Historicity of Old Church SlavonicSarbu AnaNessuna valutazione finora

- Ivo Vukcevich. Rex Germanorum Populos Sclavorum: An Inquiry Into The Origin and Early Ffotory of The Serbs/Slavs of Sarmatia, Germania, and LlyriaDocumento2 pagineIvo Vukcevich. Rex Germanorum Populos Sclavorum: An Inquiry Into The Origin and Early Ffotory of The Serbs/Slavs of Sarmatia, Germania, and LlyriaMilan SavićNessuna valutazione finora

- Classification of The Hunno-Bulgarian Loan-Words in SlavonicDocumento16 pagineClassification of The Hunno-Bulgarian Loan-Words in SlavonicAnonymous KZHSdH3LNessuna valutazione finora

- Srbi U BJRMDocumento15 pagineSrbi U BJRMВасил ГлигоровNessuna valutazione finora

- Sklavinia in Theophylact Simocatta, (Hopefully) For The Last TimeDocumento12 pagineSklavinia in Theophylact Simocatta, (Hopefully) For The Last TimeAhmedHNessuna valutazione finora

- The noble Polish family Nietecki. Die adlige polnische Familie Nietecki.Da EverandThe noble Polish family Nietecki. Die adlige polnische Familie Nietecki.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Boba, Imre, A Twofold Conquest of Hungary or Secundus Ingressus", Ungarn-Jahrbuch 12 (1982-1983) 23-41Documento19 pagineBoba, Imre, A Twofold Conquest of Hungary or Secundus Ingressus", Ungarn-Jahrbuch 12 (1982-1983) 23-41Nebojsa KartalijaNessuna valutazione finora

- A Week From The Blacksmiths Life Lutenists From Silesia and BohemiaDocumento42 pagineA Week From The Blacksmiths Life Lutenists From Silesia and BohemiaZappo22Nessuna valutazione finora

- L F 9 C: B W: Inear Rontiers IN THE Entury Ulgaria AND EssexDocumento18 pagineL F 9 C: B W: Inear Rontiers IN THE Entury Ulgaria AND EssexMichel BoyovýNessuna valutazione finora

- Sotirovic BALCANIA English Language Articles 2013Documento229 pagineSotirovic BALCANIA English Language Articles 2013Vladislav B. Sotirovic100% (1)

- Ross - Summary of KiparskyDocumento6 pagineRoss - Summary of KiparskyparthenovlahoNessuna valutazione finora

- The Making of The Slavs - Florin KurtaDocumento18 pagineThe Making of The Slavs - Florin KurtaPetrovecNessuna valutazione finora

- Some Novelties of The Runica Bulgarica - Edward TryjarskiDocumento12 pagineSome Novelties of The Runica Bulgarica - Edward TryjarskiAnonymous KZHSdH3LNessuna valutazione finora

- The Story of the Russian Land: Volume I: From Antiquity to the Death of Yaroslav the Wise (1054)Da EverandThe Story of the Russian Land: Volume I: From Antiquity to the Death of Yaroslav the Wise (1054)Nessuna valutazione finora

- SISAM, Kenneth - The Beowulf ManuscriptDocumento4 pagineSISAM, Kenneth - The Beowulf ManuscriptGesner L C Brito FNessuna valutazione finora

- The Bun Turks in Ancient GeorgiaDocumento20 pagineThe Bun Turks in Ancient GeorgiaCihan YalvarNessuna valutazione finora

- Early Journal Content On JSTOR, Free To Anyone in The WorldDocumento8 pagineEarly Journal Content On JSTOR, Free To Anyone in The WorldmaximkristianNessuna valutazione finora

- The noble Polish family Strzemie. Die adlige polnische Familie Strzemie.Da EverandThe noble Polish family Strzemie. Die adlige polnische Familie Strzemie.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sansaridou-Hendrickx, The Post-Byzantine Chronicle of CephaloniaDocumento15 pagineSansaridou-Hendrickx, The Post-Byzantine Chronicle of CephaloniaPantelisNessuna valutazione finora

- Die adlige polnische Familie Kot. The noble Polish family Kot.Da EverandDie adlige polnische Familie Kot. The noble Polish family Kot.Nessuna valutazione finora

- A Byzantine Source On The Battles of Bileća (?) and Kosovo Polje: Kydones' Letters 396 and 398 Reconsidered / Stephen W. ReinertDocumento29 pagineA Byzantine Source On The Battles of Bileća (?) and Kosovo Polje: Kydones' Letters 396 and 398 Reconsidered / Stephen W. ReinertArda KaramanNessuna valutazione finora

- Images of Authority: Papers Presented to Joyce Reynolds on the Occasion of her 70th BirthdayDa EverandImages of Authority: Papers Presented to Joyce Reynolds on the Occasion of her 70th BirthdayMary Margaret MackenzieNessuna valutazione finora

- What The Rus' Primary Chronicle Tells Us About The Origin of The Slavs and of Slavic WritingDocumento24 pagineWhat The Rus' Primary Chronicle Tells Us About The Origin of The Slavs and of Slavic WritingDanica HNessuna valutazione finora

- Ciesla Kupcy Kwart HistDocumento26 pagineCiesla Kupcy Kwart Histmoshe rosmanNessuna valutazione finora

- 1178 1829 2 PBDocumento7 pagine1178 1829 2 PBThiago RORIS DA SILVANessuna valutazione finora

- Baptism of OlgaDocumento7 pagineBaptism of Olgamarius_telea665639Nessuna valutazione finora

- Cisterciti I BaboniciDocumento22 pagineCisterciti I Babonicitormael_56Nessuna valutazione finora

- SMS - 01 - Smitek - Studia Mythologica SlavicaDocumento0 pagineSMS - 01 - Smitek - Studia Mythologica SlavicaMetasepiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Ideas and Realities in Russian Literature: With an Excerpt from Comrade Kropotkin by Victor RobinsonDa EverandIdeas and Realities in Russian Literature: With an Excerpt from Comrade Kropotkin by Victor RobinsonNessuna valutazione finora

- The Ancient Empires of The East With NotesDocumento541 pagineThe Ancient Empires of The East With NotesBasil ChulevNessuna valutazione finora

- Makedonskoto Kralstvo I Neprilikite Na HegemonotDocumento11 pagineMakedonskoto Kralstvo I Neprilikite Na HegemonotBasil ChulevNessuna valutazione finora

- Pydna, 168 BC: The Final Battle of The Third Macedonian War - Paul LeachDocumento8 paginePydna, 168 BC: The Final Battle of The Third Macedonian War - Paul LeachSonjce Marceva100% (4)

- The Fallacy of The European SatrapyDocumento33 pagineThe Fallacy of The European SatrapyBasil ChulevNessuna valutazione finora

- Glagolitic Script As A Manifestation of Sacred Knowledge PDFDocumento22 pagineGlagolitic Script As A Manifestation of Sacred Knowledge PDFBasil ChulevNessuna valutazione finora

- Hittite Vocabulary PDFDocumento189 pagineHittite Vocabulary PDFBasil ChulevNessuna valutazione finora

- Nike of SamothraceDocumento26 pagineNike of SamothraceBasil ChulevNessuna valutazione finora

- Original Sanskrit Texts On The Origin and History of The People of IndiaDocumento545 pagineOriginal Sanskrit Texts On The Origin and History of The People of IndiaBasil ChulevNessuna valutazione finora

- Simply The Best. Alexander S Last Words PDFDocumento9 pagineSimply The Best. Alexander S Last Words PDFBasil ChulevNessuna valutazione finora

- Antiquarian Researches in Illyricum, I-IV - Sir Arthur John Evans (1883-1885)Documento357 pagineAntiquarian Researches in Illyricum, I-IV - Sir Arthur John Evans (1883-1885)xhibi91% (11)

- Some Observations About The Form and Settings of The Basilica of Bargala-LibreDocumento26 pagineSome Observations About The Form and Settings of The Basilica of Bargala-LibreBasil Chulev100% (1)

- Svetite Kiril I MetodijaDocumento9 pagineSvetite Kiril I MetodijaBasil ChulevNessuna valutazione finora

- Bryges and Phrygians: Parallelism Between The Balkans and Asia Minor Through Archeological, Linguistic and Historical Evidence - Eleonora PetrovaDocumento12 pagineBryges and Phrygians: Parallelism Between The Balkans and Asia Minor Through Archeological, Linguistic and Historical Evidence - Eleonora PetrovaSonjce Marceva100% (1)

- Ancient Macedonia - The Gaul in Macedonian ArmyDocumento22 pagineAncient Macedonia - The Gaul in Macedonian ArmyBasil ChulevNessuna valutazione finora

- Prehistoric MacedoniaDocumento306 paginePrehistoric MacedoniaBasil ChulevNessuna valutazione finora

- Lexicon of The Old Russian Language, 1902. v. 2, L-P / Slovar Drevnerusskogo Jazika, 1902. Tom 2, L-PDocumento919 pagineLexicon of The Old Russian Language, 1902. v. 2, L-P / Slovar Drevnerusskogo Jazika, 1902. Tom 2, L-PBasil ChulevNessuna valutazione finora

- Lexicon of The Old Russian Language, 1912. v. 3, R-Ya / Slovar Drevnerusskogo Jazika, 1912. Tom 3, R-YaDocumento996 pagineLexicon of The Old Russian Language, 1912. v. 3, R-Ya / Slovar Drevnerusskogo Jazika, 1912. Tom 3, R-YaBasil ChulevNessuna valutazione finora

- A History of The Ancient WorldDocumento706 pagineA History of The Ancient WorldBasil Chulev100% (2)

- Ancient Fragments Containing What Remains of The Writings Of..Documento168 pagineAncient Fragments Containing What Remains of The Writings Of..Basil ChulevNessuna valutazione finora

- The Races of The Old TestamentDocumento190 pagineThe Races of The Old TestamentBasil Chulev100% (1)

- Skopje (Episcopiae Justiniana Prima) .En-LibreDocumento14 pagineSkopje (Episcopiae Justiniana Prima) .En-LibreZhidas Daskalovski100% (1)

- Proto-Indo-European Aryan Homeland of The Great Mother Goddess: Neolithic Village of Tumba Madžari in Skopje, MacedoniaDocumento11 pagineProto-Indo-European Aryan Homeland of The Great Mother Goddess: Neolithic Village of Tumba Madžari in Skopje, MacedoniaBasil ChulevNessuna valutazione finora

- Russia and Macedonia 1944-1991Documento342 pagineRussia and Macedonia 1944-1991Basil ChulevNessuna valutazione finora

- Lexicon of The Old Russian Language V. 1, A-K. 1893 / Slovar Drevnerusskogo Jazika, 1893. Tom 1, A-KDocumento771 pagineLexicon of The Old Russian Language V. 1, A-K. 1893 / Slovar Drevnerusskogo Jazika, 1893. Tom 1, A-KBasil ChulevNessuna valutazione finora

- Atlantide - The Sacred Symbols of Mu - Col. James ChurchwardDocumento182 pagineAtlantide - The Sacred Symbols of Mu - Col. James ChurchwardBasil ChulevNessuna valutazione finora

- 2005 Pericic 1964 75Documento12 pagine2005 Pericic 1964 75Basil ChulevNessuna valutazione finora

- Macedonia-Aryan Ancestral Homeland. A.A.klyosov: Where The "Slovens" and "Indo-Europeans" Came From? The DNA-Genealogy Provides The Answer.Documento29 pagineMacedonia-Aryan Ancestral Homeland. A.A.klyosov: Where The "Slovens" and "Indo-Europeans" Came From? The DNA-Genealogy Provides The Answer.Basil ChulevNessuna valutazione finora

- Canadian Aboriginal SyllabicsDocumento2 pagineCanadian Aboriginal SyllabicsBasil ChulevNessuna valutazione finora

- The Invention of The Slavic FairytaleDocumento19 pagineThe Invention of The Slavic FairytaleBasil Chulev100% (2)

- DSP Processor User GuideDocumento40 pagineDSP Processor User GuideshailackNessuna valutazione finora

- Article by Neetu MamDocumento47 pagineArticle by Neetu MamAbhishek SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- N S C Teacher Preparation Program Lesson Plan Format: Description of ClassroomDocumento3 pagineN S C Teacher Preparation Program Lesson Plan Format: Description of ClassroomCharissaKayNessuna valutazione finora

- Pub Japanese Maples Third EditionDocumento333 paginePub Japanese Maples Third EditionCesar SeguraNessuna valutazione finora

- Asking and Giving InformationDocumento9 pagineAsking and Giving InformationErni Rohani88% (16)

- 12 Watson Gender DefDocumento15 pagine12 Watson Gender Defobladi05Nessuna valutazione finora

- Java Quick ReferenceDocumento2 pagineJava Quick ReferenceRaja Rahman WayNessuna valutazione finora

- Power Revision SheetDocumento1 paginaPower Revision SheetMahjabeen BashaNessuna valutazione finora

- TOPIC 1 The Importance Meaning Nature and Assumption of ArtDocumento19 pagineTOPIC 1 The Importance Meaning Nature and Assumption of ArtMARK JAMES E. BATAGNessuna valutazione finora

- Robinson CrusoeDocumento3 pagineRobinson CrusoeAnonymous cHvjDH0ONessuna valutazione finora

- DUDRA Nhiếp Loại HọcDocumento130 pagineDUDRA Nhiếp Loại HọcThiện Hoàng100% (2)

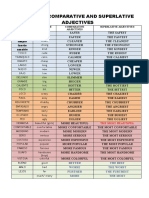

- ComparativeDocumento1 paginaComparativeGeydi Panduro DurandNessuna valutazione finora

- Exercises On Speech Acts With Answers CoveredDocumento4 pagineExercises On Speech Acts With Answers CoveredPaopao Macalalad100% (1)

- Ingles IIDocumento9 pagineIngles IIyayaNessuna valutazione finora

- A Reference Guide To The Westminster Hebrew Morphology DatabaseDocumento13 pagineA Reference Guide To The Westminster Hebrew Morphology DatabasefellliciaNessuna valutazione finora

- EmEditor Pro 14 ManualDocumento117 pagineEmEditor Pro 14 Manualvegaskink100% (1)

- IntroductionDocumento19 pagineIntroductionLovely BesaNessuna valutazione finora

- AdvancedGrammarUse4 SampleDocumento10 pagineAdvancedGrammarUse4 SampleNatalia PellegriniNessuna valutazione finora

- Simple Sentence Combining WorksheetDocumento2 pagineSimple Sentence Combining WorksheetManuel Garcia Grandy50% (2)

- MkwawaDocumento29 pagineMkwawaTommaso IndiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Reading WITHOUT MeaningDocumento7 pagineReading WITHOUT MeaningangelamaiersNessuna valutazione finora

- About//around/in/to/towards Beside/towards/to/along: He Ran The Field. He Is Walking The DoorDocumento39 pagineAbout//around/in/to/towards Beside/towards/to/along: He Ran The Field. He Is Walking The DoorAnimalNessuna valutazione finora

- An Academic Paragraph OutlineDocumento1 paginaAn Academic Paragraph OutlineHa Vu HoangNessuna valutazione finora

- P.6 English Lesson Notes Term One 2020Documento91 pagineP.6 English Lesson Notes Term One 2020Kalungi DeoNessuna valutazione finora

- English To Turkish Dictionary With Pronunciation: CLICK HEREDocumento23 pagineEnglish To Turkish Dictionary With Pronunciation: CLICK HERESoumya KhannaNessuna valutazione finora

- Explant-I User GuideDocumento28 pagineExplant-I User GuideXinggrage NihNessuna valutazione finora

- Roots ChartDocumento4 pagineRoots ChartYelitza BustamanteNessuna valutazione finora

- Time Is Money British English TeacherDocumento13 pagineTime Is Money British English TeacherMartina KačurováNessuna valutazione finora

- Grammar GuideDocumento189 pagineGrammar GuideRoberto Di PernaNessuna valutazione finora

- Filipino 15: The BasicsDocumento23 pagineFilipino 15: The BasicsJasmine Rose Cole CamosNessuna valutazione finora