Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Entrevista Adultos Mayores - Ingles

Caricato da

Maria Luisa B.zCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Entrevista Adultos Mayores - Ingles

Caricato da

Maria Luisa B.zCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Bugelli & Crowther Motivational interviewing and older people in psychiatry

special articles

Psychiatric Bulletin (20 08), 32, 23^25. doi: 10.1192/pb.bp.10 6.010405

TA N I A B U G E L L I A N D T E R R E N C E R . C R O W T H E R

Motivational interviewing and the older population

in psychiatry

Motivational interviewing is a psychological intervention

that could potentially give clinical staff working with older

people a way of tackling ambivalence and/or resistance

to change in therapy. Although it has been shown to be

effective in various spheres of mental health, we are

unaware of any publications on its use in the older

population. In this paper we discuss the main principles of

this intervention and some adaptations necessary to

meet the needs of older people (i.e. those over 65 years

old). Patients require the capacity to understand and retain

new information in order to make use of this intervention,

which hence limits its use to those who retain good

cognitive functioning. We would like to encourage the

practice of motivational interviewing both as an intervention in its own right but also in preparation for patients

requiring more specific therapies such as cognitivebehavioural therapy (CBT) or interpersonal psychotherapy.

to detect the presence or absence of optimism or pessimism in our interactions with them.

In old age services in the UK, like in most other

mental health services, there is an increased emphasis on

the use of psychological therapies (Welsh Assembly

Government, 2005). The aim of this paper is primarily to

raise awareness of a psychological technique that can be

used by clinical staff, in the day-to-day management of

older patients who are having psychological difficulties.

Psychological therapies and older people

Psychological treatments for individuals over the age of

50 years were thought to be ineffective in Freudian times

and it was only in the late 1950s that this notion was

challenged by Rechtschaffen, who provided a landmark

review of psychotherapy with older adults

(Rechtschaffen, 1959). He concluded that from a historical

perspective, the trend for the use of psychotherapy with

older people had been to use supportive approaches, in

which the therapist played a more active role. This was

based on the assumption that older people belonged to a

stereotypical group of people with:

Background

Motivational interviewing was first developed for use

with individuals with substance use disorders by William

R. Miller and Stephen Rollnick in 1991. Since then the

technique has continued to develop and is now being

used (albeit not in its pure form) for a variety of clinical

problems and lifestyle changes. Research so far supports

the efficacy of motivational interviewing techniques for

alcohol problems and drug addiction, as well as for

people with diabetes, hypertension, dual diagnosis, and

bulimia (Burke et al, 2002). Although there are some

technical considerations that may alter the practice of

motivational interviewing with older people, as will be

outlined in this paper, its basic principles remain the

same: eliciting the patients concerns, reflecting ambivalence and allowing the patient to develop a plan for

change that best suits him or her.

Working with older people can be challenging and

rewarding but at times also demoralising and demotivating, not least because this age can be associated with

more losses than gains. Patients may have multiple

problems and clinicians may unconsciously collude with

the sense of hopelessness and helplessness that the

patients might feel. More often than not patients are able

increased dependency arising from realistically difficult circumstances; the immodifiability of external circumstances

to which a neurosis may be an optimal adjustive mechanism; irreversible impairments of intellectual and learning

ability; resistance (or lack of resistance) to critical selfexamination; the economics of therapeutic investment

when life expectancy is shortened (Rechtschaffen, 1959).

Rechtschaffen emphasised that there were individual

differences in older people that the therapist ought to

consider in deciding which approach was most feasible

for which patient, and that there was no reason to

discuss geriatric psychotherapy as distinct from any other

psychotherapy unless there were distinctive features

about it.

The older people that we refer to here are those

who have experienced a diminution of their physical

health and who, in addition or perhaps as a consequence,

have become mentally ill, in particular anxious and/or

depressed. Morbidity in older people is characterised by

multiple pathology, non-specific presentation and a high

23

Bugelli & Crowther Motivational interviewing and older people in psychiatry

special

articles

discrepancy; (c) roll with resistance; and (d) support selfefficacy.

incidence of complications of both disease and treatment

(World Health Organization, 1991). Common themes

when working with older adults include grieving for

losses, fear of physical illness, disability and death, and

guilt over past failures. Such themes tend to have a

negative effect on self-efficacy. They can block the individual from moving on and hence will need to be

addressed early on in therapy to establish the impact they

are having on the persons confidence. Psychotropic

medication in older patients, particularly those in poor

physical health, is likely to be associated with more sideeffects; furthermore, it is common for patients to fear

becoming dependent.

Express empathy

A client-centred and empathic counselling style is one of

the defining characteristics of motivational interviewing.

Miller & Rollnick regard the therapeutic skill of reflective

listening, as described by Carl Rogers, to be the foundation on which clinical skilfulness in motivational interviewing is built. An empathic counsellor responds to a

persons perspectives as understandable, comprehensible

and valid within the persons own framework. Ambivalence is accepted as a normal part of human experience.

Acceptance, however, is not the same as agreement or

approval. It is possible to understand and accept a

persons perspective while not agreeing with or endorsing it.

Why motivational interviewing?

Current literature and guidelines based on best available

evidence (e.g. National Institute for Clinical Excellence,

2004 a,b ) encourage the use of CBT or interpersonal

psychotherapy for some types of anxiety and/or depressive disorders. There is evidence for the efficacy of both

these interventions in the older population. Both therapies require collaboration with the patient who, for a

variety of reasons, is not always in the action phase of

the transtheoretical model of change as defined by

Prochaska & DiClemente (1982). Up to two-thirds of

patients entering treatment for mental health problems

can, in fact, be classified as being at the pre-action stage

of change; that is, significantly ambivalent about change

so as to preclude the active adoption of change-based

strategies (Dozois et al, 2004). No stage of change

studies have been carried out as yet for older people.

However, the drop-out rates from therapies in general is

very high. In one study based on therapy termination and

persistence patterns in older patients in a community

mental health centre, a surprisingly small percentage of

the terminations were reported to be mutually agreed by

patient and therapist (8.7%) and less than half of the

patients (48.9%) attended twenty or more sessions

(Mosher-Ashley, 1994).

Motivational interviewing is a patient-centred, directive method for enhancing intrinsic motivation to change

by exploring and resolving ambivalence (Miller & Rollnick,

2002). It focuses on the persons present interests and

difficulties and tries to resolve the ambivalence by

eliciting and selectively reinforcing change talk, to move

the person towards change. Hence change is thought to

arise through its relevance to the persons own values and

concerns (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). Motivational interviewing

may be highly complimentary to CBT and interpersonal

psychotherapy as it focuses on shifting ambivalent

patients forward, increasing their probability of utilising

the tools that such therapies provide and that are

necessary for producing the change itself (Westra,

2004).

Develop discrepancy

A second general principle of motivational interviewing is

to amplify a discrepancy between the present behaviour

of patients and their broader goals and values. Many

people who seek consultation already perceive significant

discrepancy between what is happening and what they

want to happen. Yet they are also ambivalent, caught in a

conflict between the perceived benefits of the status quo

and the costs of change. A goal of motivational interviewing is to develop discrepancy, to make use of it,

increase it and amplify it until it overrides the ambivalence. Motivational interviewing seeks to accomplish this

within the person, rather than relying on external motivators such as pressure from the spouse or family.

Roll with resistance

A common and undesirable situation is for a counsellor to

be advocating change while the patient argues against it.

Not only is the ambivalent person unlikely to be

persuaded, but also they may in fact be forced in the

opposite direction. Resistance needs to be quickly identified and reframed to create a new momentum for

change. In motivational interviewing the counsellor turns

a question or problem back to the person, emphasising

that many of the insights and solutions are within the

persons own grasp. Resistance is an interpersonal

phenomenon and how the counsellor deals with it will

influence whether it increases or diminishes.

Support self-efficacy

A fourth principle of motivational interviewing involves

the concept of self-efficacy. This refers to a persons belief

in their ability to carry out and succeed with a specific

task. A counsellor may, by following the three principles

outlined above, develop a persons belief that there is an

important problem. However, if a person perceives no

hope or possibility of change, then no effort will be made

to bring this about. A general goal of motivational interviewing is to enhance the patients confidence in their

Principles of motivational interviewing

The four general principles as outlined by Miller & Rollnick

are as follows: (a) express empathy; (b) develop

24

Bugelli & Crowther Motivational interviewing and older people in psychiatry

capability to cope with obstacles and to succeed in

change. In this regard, a person may be encouraged by

their own past successes in changing behaviour or by the

success of others.

would render motivational interviewing a useful tool in

the older population. This could eventually be followed up

by research to identify those for whom it is likely to be

beneficial.

Modifying motivational interviewing

for the older person

Declaration of interest

None.

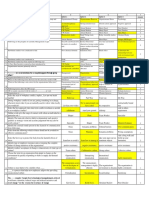

A number of physical, psychological, cognitive, social,

developmental and environmental factors will have to be

taken into consideration when applying any form of

psychological therapy in the older population. A summary

of the recommended modifications or adaptations of

psychotherapy treatments in general for older people is

given by Cook et al (2005). Such modifications also apply

to motivational interviewing. In essence, therapy will

require flexibility in planning, venue and collaboration. The

goal should be clearly outlined and continually highlighted

to reinforce the purpose and facilitate direction of treatment. Hospital visits, telephone calls or letters may be

used to deliver therapy. Consultation and coordination

with other healthcare providers is often necessary. It may

be crucial to engage carers in certain aspects of treatment and the therapist may need to lead the older adult

to conclusions more so than with younger adults. Therapists may have to proceed at a slower pace and use

repetition and other strategies to aid the encoding and

retention of information. In addition, as Cook et al (2005)

rightly point out, many older adults hold negative

stereotypes about mental health and psychological interventions that may result in reluctance to engage in

therapy. Thus an additional adaptation may have to be

orientation/socialisation into psychological therapy.

References

BURKE, B. L., ARKOWITZ, H. & DUNN, C.

(2002) The efficacy of motivational

interviewing and its adaptations: what

we know so far. In Motivational

Interviewing: Preparing People for

Change (2nd edn) (edsW. R. Miller & S.

Rollnick), pp. 217-250. Guilford Press.

COOK, J. M., GALLAGHERTHOMPSON, D. & HEPPLE, J. (2005)

Psychotherapy with older adults. In

OxfordTextbook of Psychotherapy (eds

G. O. Gabbard, J. S. Beck & J. Holmes),

pp. 381-390. Oxford University Press.

DOZOIS, D. J. A.,WESTRA, H., COLLINS,

K. A., et al (2004) Stages of change in

anxiety: psychometric properties of

the University of Rhode Island Change

Assessment (URICA) scale. Behaviour

Research andTherapy, 42, 711-729.

MILLER,W. R. & ROLLNICK, S. (2002)

Motivational Interviewing: Preparing

People for Change (2nd edn). Guilford

Press.

MOSHER-ASHLEY, P. M. (1994) Therapy

termination and persistence patterns of

elderly clients in a community mental

health center. Gerontologist, 34,180189.

Conclusion

NATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR CLINICAL

EXCELLENCE (2004a ) Quick Reference

Guide. Anxiety: Management of

Anxiety (Panic Disorder, with or

without Agoraphobia, and Generalised

Anxiety Disorder) in Adults in Primary,

It is our opinion that motivational interviewing may be a

useful intervention for those working with older people.

So far, this technique has been proven to be beneficial for

certain conditions in other age groups, both as a treatment option in its own right and as a prelude to other

forms of treatment. However, it has not been described

for use with older people. Clinical experience with this

intervention in this age group is necessary in the first

instance to help us identify more age-specific factors that

Secondary and Community Care.

NICE. http://www.nice.org.uk/

CG022quickrefguide

NATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR CLINICAL

EXCELLENCE (2004b ) Quick Reference

Guide. Depression: Management of

Depression in Primary and Secondary

Care. NICE. http://www.nice.org.uk/

CG023quickrefguide

PROCHASKA, J. O. & DICLEMENTE,

C. C. (1982) Transtheoretical therapy.

Towards a more integrative model of

change. Psychotherapy:Theory,

Research, and Practice, 19, 276-288.

RECHTSCHAFFEN, A. (1959)

Psychotherapy with geriatric patients:

a review of the literature. Journal of

Gerontology, 14, 73-84.

WELSH ASSEMBLY GOVERNMENT

(2005) Designed for Life - Creating

World Class Health and Social Care

Service for Wales in the 21st Century.

http://www.wales.nhs.uk/

documents/designed-for-life-e.pdf

WESTRA, H. A. (2004) Managing

resistance in cognitive behavioural

therapy: the application of motivational

interviewing in mixed anxiety and

depression. Cognitive Behavioural

Therapy, 33,161-175.

WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION (1991)

Health forAllTargets.The Health Policy

for Europe. WHO Regional Office for

Europe.

*Tania Bugelli Specialist Registrar, NorthWales PsychologicalTherapies

Department, North East Wales NHS Trust, email: bugellitg@hotmail.com,

Terrence R. Crowther Consultant Psychogeriatrician and Clinical Director,

Conwy and Denbighshire NHS Trust

25

special

articles

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Mosher, Et Al (2012)Documento15 pagineMosher, Et Al (2012)Maria Luisa B.zNessuna valutazione finora

- 2005 Leigh - Spirituality, Mindfulness and Substance AbuseDocumento7 pagine2005 Leigh - Spirituality, Mindfulness and Substance Abusenermal93Nessuna valutazione finora

- Entrevista Adultos Mayores - InglesDocumento3 pagineEntrevista Adultos Mayores - InglesMaria Luisa B.zNessuna valutazione finora

- Atkins Et Al 2005Documento7 pagineAtkins Et Al 2005spowieproipweoirNessuna valutazione finora

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- The Friendship Quiz: Good Friend, Bad Friend?Documento2 pagineThe Friendship Quiz: Good Friend, Bad Friend?Anonymous YC7SBiH7WpNessuna valutazione finora

- Daily Lesson Log: Republic of The Philippines Department of Education Region III Division of City of BalangaDocumento2 pagineDaily Lesson Log: Republic of The Philippines Department of Education Region III Division of City of BalangaRovilyn DizonNessuna valutazione finora

- Option 1 Option 2 Option 3 Option 4 Answers: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 A B C D E FDocumento5 pagineOption 1 Option 2 Option 3 Option 4 Answers: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 A B C D E FPrep Eve IELTSNessuna valutazione finora

- The Negative Effects of Online Gaming To Junior High Students of St. Pius X Institute Cuyapo, Nueva EcijaDocumento21 pagineThe Negative Effects of Online Gaming To Junior High Students of St. Pius X Institute Cuyapo, Nueva EcijaJericka janeNessuna valutazione finora

- Games People Play PDF Summary - Eric Berne - 12min BlogDocumento21 pagineGames People Play PDF Summary - Eric Berne - 12min BlogRovin RamphalNessuna valutazione finora

- A Quik Survey: Answer The Questions With The Best ChoiceDocumento9 pagineA Quik Survey: Answer The Questions With The Best ChoicefaizanfizaNessuna valutazione finora

- Importance of Brain BreaksDocumento7 pagineImportance of Brain Breaksapi-652921442Nessuna valutazione finora

- Pbs Facilitators ManualDocumento112 paginePbs Facilitators ManualAnonymous 782wi4Nessuna valutazione finora

- LEADERSHIPDocumento90 pagineLEADERSHIPkrishnasreeNessuna valutazione finora

- 5 Hypotheses of The Krashens TheoryDocumento7 pagine5 Hypotheses of The Krashens Theorysweetkayla.hanasanNessuna valutazione finora

- Rti - Mtss and Special Education Identification Process - EditedDocumento3 pagineRti - Mtss and Special Education Identification Process - EditedBryanNessuna valutazione finora

- ClaireDocumento24 pagineClaireMariclaire LibasNessuna valutazione finora

- Personal Development Activity TemplateDocumento2 paginePersonal Development Activity TemplateMatthew DelgadoNessuna valutazione finora

- Stress ManagementDocumento2 pagineStress ManagementKim KardashianNessuna valutazione finora

- CHART Serial Killers (Maamodt) Student NotesDocumento18 pagineCHART Serial Killers (Maamodt) Student NotesburuNessuna valutazione finora

- The Human Person As An Embodied SpiritDocumento11 pagineThe Human Person As An Embodied SpiritHasmine Lara RiveroNessuna valutazione finora

- TFN TheoriesDocumento3 pagineTFN TheoriesAngel JuNessuna valutazione finora

- CHC Mental Health Facts 101Documento16 pagineCHC Mental Health Facts 101meezNessuna valutazione finora

- Healthy Relationships PDFDocumento2 pagineHealthy Relationships PDFShawlar NaphewNessuna valutazione finora

- History of Experimental PsychologyDocumento12 pagineHistory of Experimental PsychologyamrandomaNessuna valutazione finora

- Nursing Ethics 2018Documento43 pagineNursing Ethics 2018mustafaNessuna valutazione finora

- How I Provide Social Communication Groups (1) : Structure, Strengths and StrategiesDocumento3 pagineHow I Provide Social Communication Groups (1) : Structure, Strengths and StrategiesSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeNessuna valutazione finora

- Basics of SupervisionDocumento51 pagineBasics of SupervisionFranklin Rey PacquiaoNessuna valutazione finora

- DowryDocumento10 pagineDowryanum.sherwanNessuna valutazione finora

- Transformative LearningDocumento7 pagineTransformative LearningIniobong IbokNessuna valutazione finora

- Child Abuse in Bangladesh: A Silent CrimeDocumento17 pagineChild Abuse in Bangladesh: A Silent CrimeEzaz Leo84% (19)

- DSM-5AutismSymptomChecklistforAdultDxv1 2Documento4 pagineDSM-5AutismSymptomChecklistforAdultDxv1 2GovogNessuna valutazione finora

- VolunteeringDocumento12 pagineVolunteeringНиколай ПетковNessuna valutazione finora

- Journal of Humanistic Psychology 1988Documento33 pagineJournal of Humanistic Psychology 1988SiRo WangNessuna valutazione finora

- Describe The Major Stressors in Teens EssayDocumento2 pagineDescribe The Major Stressors in Teens EssaySaadNessuna valutazione finora