Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Syphilis

Caricato da

Gandri Ali MasumDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Syphilis

Caricato da

Gandri Ali MasumCopyright:

Formati disponibili

1922

CHAPTER 327 SYPHILIS

327

SYPHILIS

EDWARD W. HOOK III

DEFINITION

Syphilis, which is a chronic infectious disease caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum, is usually acquired by sexual contact with another infected

individual. Syphilis is remarkable among infectious diseases for its large

variety of clinical manifestations. It progresses, if untreated, through primary,

secondary, and tertiary stages. The early stages (i.e., primary and secondary)

are infectious. Spontaneous healing of early lesions occurs, followed by a long

latent period. In about 30% of untreated patients, late disease of the heart,

central nervous system (CNS), or other organs may develop years after the

initial infection. Although the disease is less common now than previously, it

remains a challenge to clinicians because of its protean manifestations, and it

is of interest to biologists because of the prolonged, tenuous balance between

the host and the invading spirochete.

The Pathogen

The causative agent of syphilis, T. pallidum, is closely related to other pathogenic spirochetes (Chapter 328), including those causing yaws (T. pallidum

subspecies pertenue) and pinta (Treponema carateum). T. pallidum is a thin,

helical bacterium approximately 0.15m wide and 6 to 15m long. The

organism has 6 to 14 spirals and is tapered on either end. It is too thin to be

seen by ordinary Gram stain microscopy but can be visualized in wet mounts

by dark-field microscopy or in fixed specimens by silver stain or fluorescent

antibody methods.

Unlike most bacteria, which have protein-rich outer membranes, the

T. pallidum outer membrane appears to be composed of predominantly phospholipids, with few surface-exposed proteins. It has been hypothesized that

because of this structure, syphilis can progress despite the brisk antibody

response to nonsurface-exposed internal antigens, which is the basis for

serologic tests for the diagnosis and management of syphilis. Between the

outer membrane and the peptidoglycan cell wall are six axial fibrils; three are

attached at each end, and they overlap in the center of the organism. They are

structurally and biochemically similar to flagella and are in part responsible

for the organisms motility.

It is possible to culture T. pallidum, but sustained in vitro cultivation is not

yet possible, and yields are very low. Culture is of limited use in research and

of no use in clinical practice. All isolates studied have been susceptible to

CHAPTER 327 SYPHILIS

1923

penicillin and are antigenically similar. The only known natural hosts for

T. pallidum are humans and certain monkeys and higher apes.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

With the exception of congenital syphilis, syphilis is acquired almost exclusively by intimate contact with the infectious lesions of primary or secondary

syphilis (e.g., chancres, mucous patches, condylomata lata). Disease is usually

acquired through sexual intercourse, including anogenital and orogenital

intercourse. Health care workers are sometimes infected during the unsuspecting examination of patients with infectious lesions. Infection by contact

with fomites is extremely uncommon. Before the advent of modern blood

banking techniques, syphilis was occasionally transmitted through the transfusion of blood from persons with T. pallidum bacteremia, and occasional

parenteral transmission still occurs as a result of the sharing of contaminated

needles.

Syphilis is most common in large cities and in young, sexually active individuals. The highest rate is found in men between the age of 20 and 29 years.

In 2008, 69% of the 3141U.S. counties reported no cases of primary or

secondary syphilis, and just 26 locales accounted for about 50% of all reported

infections. The disease is most prevalent in the Southeast.

Syphilis spares no class, race, or group but is more prevalent among

persons living on the margins of society. U.S. syphilis rates are about eightfold greater in African Americans than in non-Hispanic whites (17.3 vs. 2.2

cases per 100,000 people). Increased numbers of different sexual partners

and perhaps the indiscriminate choice of partners increase the risk of acquiring sexually transmitted disease (Chapter 293). Patients with primary and

secondary syphilis name, on average, nearly three different sexual contacts

within the previous 90 days. A traditional cornerstone of syphilis control has

been the epidemiologic investigation and treatment of sexual contacts of

patients with primary or secondary lesions and patients with early latent

disease. As syphilis has become associated with drug use and anonymous sex,

epidemiologic investigations have become less efficacious.

The incidence of syphilis has generally declined worldwide for more than

100 years, with the exception of periods of war or social upheaval. With the

introduction of penicillin, there was a rapid decline in primary and secondary

syphilis, to approximately 4 cases per 100,000 people in 1957. This decline

was followed by reductions in federal expenditures for syphilis control, which

resulted in a resurgence of infectious primary and secondary syphilis in the

United States; peaks of more than 12 cases per 100,000 people were attained

several times from 1965 through the mid-1990s. Because many cases of

syphilis are not reported, the true incidence is much higher.

Over the past 40 years, syphilis epidemics have occurred serially in at least

three U.S. population subgroups. In the 1970s and 1980s, men who had sex

with other men accounted for a disproportionate number of the total cases

of infectious syphilis. Similar trends occurred in other countries. Then, after

a period of decline, U.S. syphilis rates nearly doubled from 1986 to 1990, with

50,578 cases reported in 1990 in an epidemic disproportionately affecting

multiracial heterosexual men and women and occurring contemporaneously

with an epidemic of crack cocaine use. After 1990, syphilis rates again

declined; in 2001, there were 6103 cases of primary and secondary syphilis

reported, one of the lowest numbers since 1959. The epidemic of the late

1980s probably contributed to the spread of human immunodeficiency virus

(HIV) infection (see Syphilis-HIV Interactions) and to dramatic increases in

the rate of congenital syphilis. Since 2000, syphilis rates have begun to

increase in men, especially men infected with HIV, and they have been

increasing since 2005 in women.

Patients with clinically evident late syphilis, particularly those with cardiovascular or gummatous syphilis, are becoming less common, perhaps as a

result of the effectiveness of penicillin therapy for early syphilis. However,

surveys indicate that there are still significant numbers of patients with

untreated neurologic syphilis, especially in older age groups.

Natural Course of Untreated Syphilis

The incubation period from the time of exposure to development of the

primary lesion averages approximately 21 days (range, 10 to 90 days). Initially, a painless papule develops at the site of inoculation and soon breaks

down to form a clean-based ulcerthe chancrewith raised, indurated

margins (Fig. 327-1A). The chancre persists for 2 to 6 weeks and then heals

spontaneously. Several weeks later, a secondary stage characterized by lowgrade fever, headache, malaise, generalized lymphadenopathy, and a mucocutaneous rash typically develops. There may be involvement of visceral organs.

The secondary eruption may occur while the primary chancre is still healing

FIGURE327-1. Syphilis lesions. A, Chancre in primary syphilis. B, Palmar lesions of a

coppery color in secondary syphilis. C, Mucous patch in secondary syphilis. D, Condylomata

lata in secondary syphilis (A, C, and D, From Forbes CD, Jackson WF. Color Atlas and Text of

Clinical Medicine, 3rd ed. London: Mosby; 2003; B, From Habif TP, Cambell JI, Quitadamo MJ,

etal. Skin Disease: Diagnosis and Treatment. St. Louis: Mosby; 2001.)

or up to several months after disappearance of the chancre. Secondary lesions

also heal spontaneously within 2 to 6 weeks, and the infection then becomes

latent. In more than 20% of patients with untreated latent syphilis, relapsing

lesions later develop, similar to those of the secondary stage; rarely, the

relapse takes the form of recurrence of the primary chancre. In the era before

antibiotics, late, destructive tertiary lesions involving the eyes, the CNS, the

heart, and other organs, including the skin, eventually developed in about a

third of untreated patients. These lesions may occur a few years to as long as

25 years after infection.

The incidence of late complications of untreated syphilis is currently

unknown, but it seems to be less than that seen previously. Cases of gumma

are now so rare as to be reportable.

PATHOBIOLOGY

T. pallidum may penetrate through normal mucosal membranes and minor

abrasions on epithelial surfaces. The first lesions appear at the site of primary

inoculation. The minimal number of treponemes needed to establish infection is not known but may be as low as one. Multiplication of organisms is

slow, with a division time in rabbits of approximately 33 hours. The slow

growth of treponemes in humans probably accounts in part for the protracted

nature of the illness and for the relatively long incubation period.

Syphilis is a systemic disease from the onset. Treponemes are capable of

specific attachment to host cells, but it is not known whether attachment

results in damage to the host cells. Most treponemes are found in the intercellular spaces, but they are occasionally seen within phagocytic cells. However,

there is no evidence of prolonged intracellular survival of treponemes.

T. pallidum is not known to produce toxins.

The primary pathologic lesion of syphilis is a focal endarteritis with an

increase in adventitial cells, endothelial proliferation, and the presence of an

inflammatory cuff around affected vessels. Lymphocytes, plasma cells, and

monocytes predominate in the inflammatory lesion, and polymorphonuclear

cells are seen in some cases. The vessel lumen is frequently obliterated. With

healing, there is considerable fibrosis. Treponemes may be seen in most early

lesions of syphilis and in some of the late lesions, such as the meningoencephalitis of general paresis.

1924

CHAPTER 327 SYPHILIS

Granulomatous reaction is common in secondary and late syphilis. The

granulomas are histologically nonspecific, and cases of syphilis have been

incorrectly diagnosed as sarcoidosis or other granulomatous diseases. Human

inoculation studies suggest that the pathogenesis of the gumma, which is a

granulomatous lesion, involves hypersensitivity to small numbers of virulent

treponemes introduced into a previously sensitized host.

Intracutaneous inoculation of partially purified antigens of T. pallidum into

patients with syphilis in various stages has shown that delayed cellular hypersensitivity develops only late in secondary syphilis but is uniformly present

in latent syphilis. There may be temporary hyporesponsiveness of lymphocytes to treponemal antigens in patients with primary and secondary syphilis.

It is possible that the waxing and waning of lesions in early syphilis depend

on the balance between the development of effective cellular immunity and

the suppression of thymus-derived lymphocyte function.

The host also responds to infection by producing numerous antibodies; in

some instances, circulating immune complexes may be formed as well. For

example, nephrotic syndrome has occasionally been recognized in secondary

syphilis, and renal biopsy specimens from such patients have shown membranous glomerulonephritis characterized by focal subepithelial basement

membrane deposits containing immunoglobulin G (IgG), C3, and treponemal antibody.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Primary Syphilis

The typical lesion of primary syphilis, the chancre, is a painless, clean-based,

indurated ulcer (see Fig. 327-1A). The chancre starts as a papule, but then

superficial erosion results in ulceration. The borders of the ulcer are raised,

firm, and indurated. Occasionally, secondary infections change the appearance and cause a painful lesion. Most chancres are single, but multiple ulcers

are sometimes seen, particularly when skin folds are apposed (i.e., kissing

chancres). An untreated chancre heals in several weeks and leaves a faint scar.

The chancre is usually associated with regional adenopathy, which may be

unilateral or bilateral. The regional nodes are movable, discrete, and rubbery.

If the chancre occurs in the cervix or the rectum, the affected regional iliac

nodes are not palpable.

Chancres can occur at any site of potential inoculation by direct contact,

with most occurring in anogenital locations. Chancres may also be seen in

the pharynx, on the tongue, around the lips, on the fingers, on the nipples,

and in other diverse areas. The morphology depends in part on the area of

the body where they occur and on the hosts immune response. Chancres in

previously infected individuals may be small and remain papular. Chancres

of the finger may appear more erosive and can be quite painful. Chancres of

the anal canal may be missed in men who have sex with men unless a careful

examination is undertaken.

Secondary Syphilis

Between 4 and 8 weeks after the appearance of the primary chancre, signs

and symptoms of secondary syphilis typically develop. Symptoms may

include malaise, fever, headache, sore throat, and other systemic complaints.

Most patients have generalized lymphadenopathy, including involvement of

the epitrochlear nodes. Approximately 30% of patients have evidence of a

healing chancre, although many patients (including a disproportionate

number of women and of men who have sex with men) give no history of a

primary lesion.

At least 80% of patients with secondary syphilis have cutaneous or

mucocutaneous lesions at some point in their illness. The diagnosis is generally first suspected on the basis of the cutaneous eruption. The rash is

often minimally symptomatic, and many patients with late syphilis do not

recall primary or secondary lesions. The rashes are quite varied in appearance but have certain characteristic features. The lesions are usually widespread, are symmetrical in distribution, and are frequently pink, coppery,

or dusky red (particularly the earliest macular lesions). They are generally

nonpruritic, although occasional exceptions have been reported, and they

are rarely vesicular or bullous in adults. They are indurated, except for the

very earliest macular lesions, and frequently have a superficial scale (i.e.,

papulosquamous lesions). The lesions tend to be polymorphic and rounded,

and on healing, they may leave residual pigmentation or depigmentation.

They may be quite faint and difficult to visualize, particularly on darkskinned individuals.

The earliest pink macular lesions are typically seen on the trunk, with

later spread to the rest of the body. The face is often spared, except around

the mouth. Subsequently, a papular rash appears that is usually generalized

but is quite marked on the palms and soles (Fig. 327-1B). These rashes

are often associated with a superficial scale and may be hyperpigmented.

When the rash occurs on the face, it may be pustular and resemble acne

vulgaris. Occasionally, the scale may be so great that it resembles psoriasis.

Ulceration may occur and produce lesions resembling ecthyma. In malnourished or debilitated patients, extensive and destructive ulcerative lesions

with a heaped-up crust may occur, the so-called rupial lesions. Lesions

around the hair follicles may result in patchy alopecia of the beard or

scalp.

Ringed or annular lesions may occur, especially around the face, and particularly on dark-skinned individuals. A lesion at the angle of the mouth or

the corner of the nose may have a central linear erosion, the so-called split

papule.

The palate and pharynx may be inflamed. In approximately 30% of secondary syphilis patients, so-called mucous patches (Fig. 327-1C) develop; these

slightly raised, oval areas are covered by a grayish white membrane that, when

raised, reveals a pink base that does not bleed. These lesions may be seen on

the genitalia, in the mouth, or on the tongue; like condylomata lata, they are

highly infectious.

In warm, moist areas such as the perineum, large, pale, flat-topped papules

may coalesce to form condylomata lata (Fig. 327-1D). Papules may also be

seen in the axilla and rarely occur in a generalized form. They are extremely

infectious. These papules are not to be confused with the common venereal

warts (i.e., condylomata acuminata), which are small, often multiple, and

more sharply raised than condylomata lata.

Other manifestations of secondary syphilis include hepatitis, which has

been reported in up to 10% of patients in some series. Jaundice is rare, but

an elevated alkaline phosphatase level is common. Liver biopsy reveals small

areas of focal necrosis and mononuclear infiltrate or periportal vasculitis.

Spirochetes can often be visualized with silver stains. Periostitis with widespread lytic lesions of bone has been reported occasionally; bone scanning

appears to be a sensitive test for early syphilitic osteitis. An immune complex

type of nephropathy with transient nephrotic syndrome has been documented rarely. There may be iritis or an anterior uveitis. Between 10 and 30%

of patients have pleocytosis in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), but symptomatic

meningitis is seen in less than 1% of patients. Symptomatic gastritis may

occur.

Relapsing Syphilis

After resolution of the primary or secondary skin lesions, 20 to 30% of

patients experience cutaneous recurrences. Recurrent lesions may be fewer

or more firmly indurated than the initial lesions. Like the typical lesions of

primary or secondary syphilis, they are infectious for exposed sexual

partners.

Latent Syphilis

By definition, latent syphilis is the stage at which there are no clinical signs

of syphilis and the CSF is normal. Latency, which begins when the first attack

of secondary syphilis has passed and may last for a lifetime, is usually detected

by reactive serologic tests for syphilis (see Diagnosis). Congenital syphilis

must also be excluded before the diagnosis of latent syphilis can be made.

Patients may or may not have a clinical history of earlier primary or secondary

syphilis.

Latency has been divided into two stages: early and late. Most infectious

relapses occur in the first year, and epidemiologic evidence shows that the

most infectious period is during the first year of infection. Early latency is

therefore defined as the first year after resolution of the primary or secondary

lesions, or as a newly reactive serologic test for syphilis in an otherwise

asymptomatic individual who has had a negative serologic test within the

preceding year. Late latent syphilis is ordinarily not infectious, except for

pregnant women, who can transmit infection to the fetus after many years.

Most cases of latent syphilis are most accurately called latent syphilis of

unknown duration and should be treated in the same manner as late latent

syphilis (see later).

Late Syphilis

Late syphilis (Table 327-1) is usually slowly progressive, although certain

neurologic syndromes may have a sudden onset because of endarteritis

and CNS thrombosis. Late syphilis is not infectious through sexual contact.

Any organ of the body may be involved, but three main types of disease

can be distinguished: late benign (gummatous), cardiovascular, and

neurosyphilis.

CHAPTER 327 SYPHILIS

TABLE 327-1 NEWLY DIAGNOSED TERTIARY SYPHILIS IN 105

PATIENTS IN DENMARK, 1961-1970

TYPE OF TERTIARY SYPHILIS

Neurosyphilis

Asymptomatic

Tabes dorsalis

General paresis

Meningovascular

Optic atrophy

Cardiovascular syphilis

Aortic insufficiency

Aortic aneurysm

Uncomplicated aortitis

Late benign syphilis (gumma)

NO. OBSERVED*

72

45

11

13

1

2

44

16

13

15

4

*Some patients had more than one form of late syphilis.

Autopsy diagnoses only.

Late Benign Syphilis

In the penicillin era, gummas are rare. They typically develop 1 to 10 years

after initial infection and may involve any part of the body. Although gummas

may be destructive, they respond rapidly to treatment and are therefore relatively benign. Histologically, the gumma is a granuloma.

Gummas may be solitary or multiple and most often come to medical

attention as space-occupying lesions. They are usually asymmetrical and are

often grouped. Gummas may start as a superficial nodule or as a deeper lesion

that breaks down to form punched-out ulcers. They are ordinarily indolent,

slowly progressive, and indurated on palpation. There is often central healing,

with an atrophic scar surrounded by hyperpigmented borders. Cutaneous

gummas may resemble other chronic granulomatous ulcerative lesions

caused by tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, leprosy, and other deep fungal infections.

Precise histologic diagnosis may not be possible. However, syphilitic gummas

are the only such lesions to heal dramatically with penicillin therapy.

Gummas may also involve deep visceral organs, particularly the respiratory

tract, gastrointestinal tract, and bones. In addition, they may involve the

larynx or the pulmonary parenchyma. Gummas of the stomach may masquerade as carcinoma of the stomach or lymphoma. Gummas of the liver

were once the most common form of visceral syphilis and often manifested

as hepatosplenomegaly and anemia and occasionally as fever and jaundice.

Skeletal gummas typically produce lesions in the long bones, skull, and clavicle; a characteristic symptom is nocturnal pain. Radiologic abnormalities,

when present, include periostitis and lytic or sclerotic, destructive osteitis.

Cardiovascular Syphilis

The primary cardiovascular complications of syphilis are aortic insufficiency

(Chapter 75) and aortic aneurysm (Chapter 78), usually of the ascending

aorta. Less commonly, other large arteries may be affected, and involvement

of the coronary ostia rarely results in coronary insufficiency. All these complications are caused by obliterative endarteritis of the vasa vasorum, with

resultant damage to the intima and media of the great vessels. This damage

results in dilation of the ascending aorta, but the valve cusps remain normal.

An aneurysm occasionally manifests as a pulsating mass bulging through the

anterior chest wall. Syphilitic aortitis may also involve the descending aorta

proximal to the renal arteries.

Cardiovascular syphilis usually begins within 5 to 10 years of the initial

infection but may not manifest clinically until 20 to 30 years later. Cardiovascular syphilis does not occur after congenital infectiona phenomenon that

remains unexplained.

Asymptomatic aortitis is best diagnosed by visualizing linear calcifications

in the wall of the ascending aorta by radiography. The signs of syphilitic aortic

insufficiency are the same as for aortic insufficiency of other causes. In aortic

insufficiency resulting from dilation of the aortic ring, the decrescendo

murmur is often loudest along the right sternal margin. Syphilitic aneurysms

may be fusiform but are more typically saccular and do not lead to aortic

dissection. Between 10 and 20% of patients with cardiovascular syphilis have

coexistent neurosyphilis.

Neurosyphilis

CNS involvement occurs throughout the natural history of syphilis. Neurosyphilis can be divided into five groups: asymptomatic, syphilitic meningitis,

1925

meningovascular syphilis, tabes dorsalis, and general paresis. Asymptomatic

neurosyphilis can occur at any time, whereas syphilitic meningitis is most

common during the secondary stage of infection. Meningovascular syphilis,

tabes dorsalis, and general paresis are typically manifestations of late syphilis.

The divisions are not absolute, and overlap between syndromes is typical.

Current cases of neurosyphilis are likely to be variants of the classic syndromes, possibly as a result of the use of antimicrobial agents for other

diseases.

Syphilitic Meningitis

Acute to subacute aseptic meningitis can occur at any time after the primary

stage, but it usually occurs within the first year of infection. It frequently

involves the base of the brain and may result in unilateral or bilateral cranial

nerve palsies. Mild aseptic meningitis may be relatively common in patients

with early syphilis, but severe disease occurs in only about 1.5% of untreated

patients. Syphilitic meningitis typically resolves without treatment.

Meningovascular Syphilis

Some patients have sufficient endarteritis and perivascular inflammation to

result in cerebrovascular thrombosis and infarction, generally 5 to 10 years

after the initial infection. Patients frequently have associated aseptic meningitis. Most cerebrovascular accidents are not caused by syphilitic arteritis,

even in patients with a reactive serologic test result for syphilis. However,

syphilis should be considered a potential cause in relatively young patients

with a history of syphilis and without other risk factors for cerebrovascular

accidents.

Tabes Dorsalis

Tabes dorsalis, which appears to be far less common than in the pre-penicillin

era, is a slowly progressive, degenerative disease that involves the posterior

columns and posterior roots of the spinal cord and results in progressive loss

of peripheral reflexes, impairment of vibration and position sense, and progressive ataxia. There may be chronic destructive changes in the large joints

of the affected limbs in far-advanced cases (i.e., Charcots joints). Incontinence of the bladder and impotence are common. Sudden and severely

painful crises of uncertain origin are a characteristic part of the syndrome.

These features typically involve the lower extremities but can occur at any

site. Severe, sharp abdominal pain may lead to exploratory surgery. These

attacks may be triggered by exposure to cold or other stresses or may arise

with no obvious precipitating cause.

Optic atrophy is seen in 20% of cases. In 90% of patients, the pupils are

bilaterally small and fail to constrict further in response to light, but they do

respond normally to accommodation (i.e., Argyll Robertson pupils).

The onset of tabes dorsalis is usually first noticed 20 to 30 years after the

initial infection. Its cause is unclear, and spirochetes cannot be demonstrated

in the posterior column or dorsal root.

General Paresis

This form of neurosyphilis is a chronic meningoencephalitis resulting in the

gradual and progressive loss of cortical function. It typically occurs 10 to 20

years after the initial infection. Pathologically, there is a perivascular and

meningeal chronic inflammatory reaction, with thickening of the meninges,

granular ependymitis, degeneration of the cortical parenchyma, and abundant spirochetes in tissues. In the United States, first admissions to mental

hospitals because of syphilitic psychosis declined from 7694 in 1940 to 154

in 1968, the last year for which definite figures are available.

In its early stages, general paresis results in nonspecific symptoms of early

dementia, such as irritability, fatigability, headaches, forgetfulness, and personality changes. Later, there is impaired memory, defective judgment, lack

of insight, confusion, and often depression or marked elation. Patients may

be delusional, and seizures sometimes occur. There may also be loss of other

cortical functions, including paralysis or aphasia.

Physical signs are primarily those of the altered mental status. Cranial

nerve palsies are uncommon, and optic atrophy is rare. The complete Argyll

Robertson pupil is also uncommon, but irregular or otherwise abnormal

pupils are not infrequent. Peripheral reflexes are often somewhat increased.

Syphilis-HIV Interactions

Syphilis, like other genital ulcer diseases, is associated with a three- to fivefold increased risk for acquisition of HIV infection. Presumably, genital ulcers

act as portals of entry through which HIV may more readily infect exposed

individuals. As a result, HIV serologic testing 3 months after a diagnosis of

1926

CHAPTER 327 SYPHILIS

syphilis is recommended for all patients. Conversely, in individuals with HIV

infection who acquire syphilis, the natural history of the infection may be

modified. HIV-infected syphilis patients are somewhat more likely than nonHIV-infected patients to present initially with secondary syphilis. HIVinfected secondary syphilis patients are also more likely than HIV-negative

secondary syphilis patients to have coexistent chancres, suggesting that the

healing of chancres is delayed or the appearance of secondary manifestations

is accelerated in the presence of HIV coinfection.

Congenital Syphilis

Congenital syphilis results from the transplacental, hematogenous spread of

syphilis from the mother to the fetus. The incidence of congenital syphilis

diagnoses in the United States fell below 1000 per year for the first time in

1975, and fewer than 500 cases occurred each year until 1988, when the

epidemic of syphilis in adults led to parallel increases in congenital infections.

From 1990 through 1993, more than 3000 new cases of congenital syphilis

were reported each year. A Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL)

test should be performed in all expectant mothers at the beginning of pregnancy and should be repeated near the end of pregnancy in women living in

areas where syphilis is relatively common.

The risk for fetal infection is greatest in the early stages of untreated maternal syphilis and declines slowly thereafter, but the mother can infect her fetus

during at least the first 5 years of her infection. Adequate treatment of the

mother before the 16th week of pregnancy usually prevents clinical illness in

the neonate. Later treatment may not prevent late sequelae of the disease in

the child. Untreated maternal infection may result in stillbirth, neonatal

death, prematurity, or syndromes of early or late congenital syphilis in surviving infants.

Manifestations of early congenital syphilis are often seen in the perinatal

period but may not develop until the infant has been discharged from the

hospital. The disease resembles secondary syphilis in adults, except that the

rash may be vesicular or bullous. The child often has rhinitis, hepatosplenomegaly, hemolytic anemia, jaundice, and pseudoparalysis (i.e., immobility of

one or more extremities) as a result of painful osteochondritis. There may be

thrombocytopenia and leukocytosis. The early stages of congenital syphilis

must be differentiated from congenital rubella, cytomegalovirus infection,

toxoplasmosis, bacterial sepsis, and other diseases.

Late congenital syphilis is defined as congenital syphilis diagnosed more

than 2 years after birth. The disease may remain latent, with no manifestations

of late damage. Cardiovascular alterations have not been observed in patients

with congenital syphilis. Neurologic manifestations are common and may

include eighth cranial nerve deafness and interstitial keratitis. Periostitis may

result in prominent frontal bones of the skull, depression of the bridge of the

nose (saddle nose), poor development of the maxilla, and anterior bowing of

the tibias (saber shins). There may be late-onset arthritis of the knees (Cluttons joints). The permanent dentition may show characteristic abnormalities

known as Hutchinsons teeth; the upper central incisors are widely spaced,

centrally notched, and tapered in the manner of a screwdriver. The molars

may show multiple poorly developed cusps (mulberry molars).

DIAGNOSIS

Dark-Field Examination

The most definitive means of syphilis diagnosis is finding spirochetes of

typical morphology and motility in lesions of early acquired or congenital

syphilis. Dark-field examination is often positive in cases of primary syphilis

and in patients with the moist mucosal lesions of secondary and congenital

syphilis. The result may occasionally be positive for aspirates of lymph nodes

in secondary syphilis. False-negative results may occur in primary syphilis

because of the application of soaps, antiseptics, or other compounds toxic to

T. pallidum to the lesions. A single negative result is therefore insufficient to

exclude syphilis. For high-risk individuals (e.g., drug users, homosexually

active men), it is appropriate to treat presumptively based on suspicious

lesions after performing serologic tests. Confusion may also arise because of

the presence of spirochetes that are morphologically indistinguishable from

T. pallidum organisms in the mouth, particularly around the gingival margins.

Living T. pallidum organisms demonstrate gradual motion to and fro, rotational movement around the long axis, and rather sudden 90-degree flexing

near the center of the organism. Because most physicians do not have the

proper equipment and are not familiar with dark-field microscopy techniques, public health authorities can be called for assistance. T. pallidum may

also be demonstrated in biopsy or pathologic specimens by fluorescent antibody stains or by silver stains.

TABLE 327-2 SEROLOGIC TESTS FOR SYPHILIS

TYPE

USE

NONTREPONEMAL (ANTICARDIOLIPIN) ANTIBODIES

VDRL (slide flocculation)

RPR (circle card) (agglutination)

Screening, quantitation of response to

treatment

Screening, quantitation of response to

treatment

SPECIFIC TREPONEMAL ANTIBODIES

FTA-ABS (immunofluorescence with

absorbed serum)

TP-PA (microhemagglutination)

EIA

Confirmatory, diagnostic; not for routine

screening

Similar to FTA-ABS but can be

quantified and automated

Confirmatory and increasingly used for

screening; automated

EIA = enzyme immunoassay; FTA-ABS = fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test; RPR =

rapid plasma regain test; TP-PA = Treponema pallidumparticle agglutination; VDRL = Venereal

Disease Research Laboratory.

TABLE 327-3 FREQUENCY OF POSITIVE SEROLOGIC TESTS

IN UNTREATED SYPHILIS

STAGE

Primary

VDRL (%)

70

FTA-ABS (%)

85

TP-PA (%)

50-60

Secondary

99

100

100

Latent or late

70

98

98

FTA-ABS = fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test; TP-PA = Treponema pallidumparticle

agglutination; VDRL = Venereal Disease Research Laboratory.

Serologic Tests

Two basic types of serologic tests (Table 327-2) are widely used to diagnose

infection with T. pallidum: (1) nontreponemal tests that detect antibodies

reactive with diphosphatidylglycerol (cardiolipin), which is a normal component of many tissues, and (2) tests that detect antibodies to specific treponemal antigens.

Nontreponemal Tests

The standard tests to detect anticardiolipin antibody are the VDRL and rapid

plasma reagin (RPR) tests, which are slide flocculation tests. The VDRL and

RPR are readily quantified, so they are the tests of choice for monitoring

patients responses to treatment. The relative proportion of patients with a

false-positive VDRL result depends on the prevalence of syphilis in the community; the lower the prevalence of syphilis, the higher the proportion of

reactive VDRL test results from nonsyphilitic causes.

The VDRL test begins to turn positive less than 1 week after onset of the

chancre; thus, a nonreactive VDRL test does not exclude primary syphilis,

particularly if the lesion is less than 1 week old. The VDRL test result is positive in 99% of patients with secondary syphilis (Table 327-3). Patients with

advanced HIV infection may have negative test results, and some patients

have such high titers of antibody that they are in antibody excess; dilution of

their serum paradoxically results in conversion of a negative test result to a

positive one, the so-called prozone reaction. VDRL reactivity tends to diminish in later stages of syphilis, and only about 70% of patients with cardiovascular or neurosyphilis have positive VDRL test results.

The quantitative titer of the VDRL or RPR test is somewhat useful in diagnosis and is quite useful for monitoring the therapeutic response. The titer is

reported as the highest dilution that gives a positive response. Most patients

with secondary syphilis have titers of at least 1:16. Most patients with falsepositive VDRL test results have titers of less than 1:8. No single titer is

diagnostic by itself. Significant rises (four-fold or greater) in paired sera,

however, strongly indicate acute syphilis.

Treponemal Tests

Several types of treponemal tests are widely used. Agglutination of particles

to which T. pallidum antigens have been fixed is the basis of the T. pallidum

particle agglutination (TP-PA) test. More recently, treponemal enzyme

CHAPTER 327 SYPHILIS

immunoassays (EIAs) have become available from several manufacturers and

have gained favor because of their low cost and ease of use.

The treponemal tests are best used to confirm that persons with reactive

nontreponemal tests have antibodies to T. pallidum. Results of treponemal

tests are not reliably quantified. They are sensitive and have a high degree

of specificity, in that only approximately 1% of normal individuals have reactive treponemal tests. They are reactive in 85% of patients with primary

syphilis, 99% with secondary syphilis, and at least 95% with late syphilis.

They may therefore be the only test with a positive result in patients with

cardiovascular or neurologic syphilis. For patients with late syphilis, treponemal tests often remain reactive for life, despite adequate therapy. The fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) test is reported in terms

of relative brilliance of fluorescence, from borderline to 4 plus, and most

laboratories report only tests with 2 plus or greater reactivity as positive. For

patients lacking historical or clinical evidence of syphilis but with a reactive

FTA-ABS test result, the test should be repeated. Use of another treponemal

test, such as the TP-PA test, may be helpful in problem cases. The TP-PA

test is slightly less sensitive than the VDRL or FTA-ABS test in primary

syphilis. Its sensitivity and specificity are otherwise nearly identical to those

of the FTA-ABS test.

EIAs for the detection of antitreponemal antibodies use cloned T. pallidum

antigens generated from bacterial expression systems. EIA serologic tests

permit the screening of large numbers of sera and have performance characteristics (sensitivity, specificity, predictive values) similar to those of other

treponemal tests. Persons with syphilis diagnosed by treponemal antigen

EIAs should be tested with quantitative nontreponemal tests such as the

VDRL or RPR for confirmation and to permit the use of these tests to evaluate the subsequent response to therapy.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of a genital ulcer (Chapter 293) includes genital

herpes (Chapter 382), chancroid (Chapter 309), lymphogranuloma venereum (Chapter 326), and a number of other ulcerative processes. Classically,

herpetic ulcers are multiple, painful, superficial, and, if seen early, vesicular.

However, atypical manifestations may be indistinguishable from a syphilitic

chancre. Genital herpes is much more common than syphilis and is now the

most common cause of a typical chancre in North America. Syphilitic

chancres may also be coinfected with herpes simplex virus in about 15% of

cases. The ulcers of chancroid are usually painful, often multiple, and frequently exudative and nonindurated. Lymphogranuloma venereum may

produce a small, papular lesion associated with regional adenopathy. Other

conditions that must be distinguished include granuloma inguinale (Chapter

324), drug eruptions, carcinoma, superficial fungal infections (Chapter 446),

traumatic lesions, and lichen planus (Chapter 446). In most cases, the final

distinction is based on dark-field examination, which is positive only in syphilis, and on serologic test results.

The differential diagnosis of the skin lesions of secondary syphilis includes

pityriasis rosea (Chapter 446), which can be differentiated by the occurrence

of lesions along lines of skin cleavage and frequently by the presence of a

herald patch. Drug eruptions, acute febrile exanthems, psoriasis, lichen

planus, scabies, and other diseases must also be considered in some cases. A

mucous patch may superficially resemble oral candidiasis (i.e., thrush). Infectious mononucleosis (Chapter 385) may appear very similar to secondary

syphilis, with sore throat, generalized adenopathy, hepatitis, and a generalized

rash. Hepatitis (Chapter 150) may also cause confusion.

False-Positive Serologic Test Results for Syphilis

The VDRL or RPR test is reactive in patients with other treponemal diseases

such as pinta, yaws, and endemic syphilis (Chapter 328). These tests may also

be falsely reactive in persons who do not have treponemal infections based

on a negative clinical history or negative results of serum treponemal tests.

Acute (<6 months) false-positive VDRL test results occur with low frequency in patients with atypical pneumonia, malaria, and other bacterial or

viral infections, and they may occur after smallpox or other vaccinations as

well. Chronic false-positive VDRL test results (persisting >6 months) are

relatively common in patients with autoimmune disorders such as systemic

lupus erythematosus (SLE; Chapter 274), parenteral drug users, HIVinfected patients, patients with leprosy, and the aged. Between 8 and 20% of

patients with SLE have false-positive VDRL test results. Chronic false-positive VDRL test results in female patients 20 years or younger indicate a significant risk for the future development of SLE, thyroiditis, or other

autoimmune disorders. As many as a third of parenteral drug users have

1927

false-positive VDRL test results. More than 1% of persons 70 years old and

10% of those older than 80 also have low-titer, false-positive VDRL test

results. In most cases of false-positive VDRL tests, the titer is less than 1:8,

although a few patients with lymphoma and other diseases have very hightiter, false-positive results.

There is also an increased incidence of false-positive treponemal test

results in other chronic inflammatory diseases associated with hyperglobulinemia, including rheumatoid arthritis and biliary cirrhosis. Occasionally,

reproducible positive FTA-ABS results are obtained in patients with no clinical or historical evidence of syphilis and no evidence of diseases typically

associated with false-positive FTA-ABS results. If the diagnosis is in doubt

and if the patient is not allergic to penicillin, it is often prudent to treat for

possible syphilis.

Neurosyphilis

Asymptomatic neurosyphilis is diagnosed when there are CSF abnormalities,

such as lymphocytic pleocytosis, protein elevation, or a reactive VDRL test

result, in a syphilis patient in the absence of signs and symptoms of neurologic disease. Although numerous other processes can cause CSF pleocytosis or protein elevations, false-positive CSF VDRL test results are rare

in the absence of a traumatic tap. If the CSF is normal 2 years or longer

after the initial infection, a positive CSF finding is not likely to develop

later. Routine lumbar punctures to examine CSF are not indicated in early

syphilis unless the patient is known to have HIV infection. Lumbar puncture

in HIV-infected persons with early syphilis is the subject of controversy.

Although a nonreactive CSF FTA-ABS result may be useful to rule out the

diagnosis, no diagnosis of neurosyphilis should be based solely on the CSF

FTA-ABS test.

In syphilitic meningitis, the CSF shows a lymphocytic pleocytosis, with

increased protein and usually normal glucose concentrations. The CSF

VDRL test is nearly always reactive. Rarely, the CSF glucose concentration is

decreased. Without treatment, syphilitic meningitis generally resolves,

similar to the course of other manifestations of early syphilis. This syndrome

can mimic tuberculous or fungal meningitis or nonpurulent meningitis of

various causes.

In tabes dorsalis, the VDRL test for serum is nonreactive in as many as 30

to 40% of patients, and 10 to 20% of patients (even before the advent of

penicillin) have normal CSF VDRL results. The FTA-ABS test for serum is

nearly always reactive.

In general paresis, the CSF is nearly always abnormal, with lymphocytic

pleocytosis and an increased total protein concentration. The VDRL test is

usually reactive for CSF and serum.

Congenital Syphilis

Because many infants with congenital syphilis may be clinically normal at

birth but develop serious, symptomatic disease some weeks later, it is important to determine whether a newborn with a reactive VDRL or FTA-ABS test

result has passively transferred maternal antibody or is actively infected. If the

mother has been adequately treated for syphilis during pregnancy and the

infant is clinically normal at birth, one option is to monitor the infant carefully by serial examinations and VDRL titers. If the reactive VDRL result for

the infant is caused by passively transferred maternal antibody, the titer will

fall markedly in the first 2 months of life; a rising titer indicates active disease

and the need for treatment. However, the risk of improper follow-up of

VDRL-positive but clinically normal neonates makes the immediate empirical administration of effective therapy an attractive alternative.

TREATMENT

T. pallidum is inhibited by less than 0.01g/mL of penicillin G. Because

treponemes divide slowly and penicillin acts only on dividing cells, it is necessary to maintain serum levels of penicillin for many days (Table 327-4).

Early Infectious Syphilis

Early syphilis (<1 year) can be treated with a single injection of 2.4 million

U of benzathine penicillin G, which provides low but effective serum levels for

more than 2 weeks and cures approximately 95% of patients. It is not necessary to examine CSF at this stage because penicillin prevents the later development of neurosyphilis.

Individuals with other sexually transmitted diseases may have been exposed

to syphilis at the time they became infected. Treatment with a single dose of

-lactam antibiotics (penicillins, cephalosporins), which provide relatively high

1928

CHAPTER 327 SYPHILIS

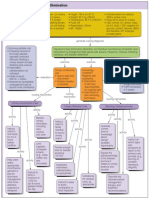

TABLE 327-4 PENICILLIN TREATMENT FOR SYPHILIS AS RECOMMENDED BY THE U.S. PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE

Dosage and Administration

BENZATHINE PENICILLIN G

Total of 2.4 million U; single IM dose of two

injections of 1.2 million U in one session

AQUEOUS BENZYLPENICILLIN G OR PROCAINE

PENICILLIN G

Total of 4.8 million U IM in doses of 600,000U/day for 8

consecutive days

Late latent (>1yr) or when CSF was not examined

in latency; cardiovascular syphilis, late benign

(cutaneous, osseous, visceral gumma)

Total of 7.2 million U IM in doses of 2.4 million

U at 7-day intervals over a 21-day period

Total of 9 million U IM in doses of 600,000U/day over a

15-day period

Symptomatic or asymptomatic neurosyphilis

2-4 million U aqueous (crystalline) penicillin G

IV q4h for at least 10 days

2-4 million U procaine penicillin IM daily and probenecid

500mg orally four times daily, for 10-14 days

CSF normal: Total of 50,000U/kg IM in a

single or divided dose at one session

CSF normal: Same as for early congenital

syphilis, up to 2.4 million U

CSF abnormal: Total of 50,000U/kg/day IM for 10

consecutive days

CSF abnormal: 200,000-300,000U/kg/day aqueous

crystalline penicillin IV for 10-14 days

INDICATIONS FOR SYPHILIS THERAPY*

Primary, secondary, and early latent syphilis (<1yr);

epidemiologic treatment

Congenital

Infants

Older children

*In pregnancy, treatment depends on the stage of syphilis.

Individual doses can be divided for injection in each buttock to minimize discomfort.

For aqueous penicillin, give in two divided intravenous doses per day; for procaine penicillin, give as one daily dose intramuscularly.

CSF = cerebrospinal fluid.

serum levels for a brief period, is ineffective in established early syphilis but is

curative if the disease is still in the incubating stage. The ceftriaxone regimen

used for gonorrhea (Chapter 307) is probably curative for incubating syphilis,

but careful follow-up is indicated if there is reason to suspect exposure to

syphilis in a patient treated for gonorrhea with ceftriaxone. Single-dose

therapy with 2.0g of azithromycin administered orally was as effective as

benzathine penicillin therapy in several studies of early syphilis, but treatment

failures have been reported in persons with coexistent HIV infection.1 Currently, azithromycin should not be used for the treatment of early syphilis

unless close follow-up can be ensured.

For patients allergic to penicillin, 100mg of doxycycline orally twice daily

for 14 days is recommended. Particularly careful follow-up is necessary for

patients treated with drugs other than penicillin because they may not be fully

compliant with these prolonged courses of oral therapy and these regimens

have been less fully evaluated clinically. Ceftriaxone, given in doses of 500mg

to 1.0g intramuscularly daily for 10 days, may be effective but has been

studied only in small numbers of patients with syphilis. Quinolone antibiotics

have essentially no effect on syphilis.

Syphilis in Pregnancy

Syphilis of More than 1 Years Duration

Proper treatment of the mother usually prevents active congenital syphilis

in the neonate. However, infected infants may be clinically normal at birth,

and the infant may be seronegative if the mothers infection was acquired

late in pregnancy. The infant should be treated at birth if the mother has

received no treatment or inadequate treatment or has been treated with

drugs other than penicillin, if the mother has not yet responded to possibly

effective therapy, or if the infant cannot be carefully monitored for several

months after birth. The infants CSF should be examined before treatment.

If the CSF is normal, the child can be treated with a single intramuscular

injection of 50,000 U/kg (up to 2.4 million U) of benzathine penicillin G. If

the CSF is abnormal, the infant should be treated with 50,000 U/kg of

aqueous penicillin G given intramuscularly or intravenously twice daily for

a minimum of 10 days. Alternatively, a single daily intramuscular injection

of 50,000 U/kg of procaine penicillin may be given for 10 days. Antimicrobial

agents other than penicillin are not recommended for treating congenital

syphilis.

Prolonged therapy with intramuscular injections of 2.4 million U of benzathine penicillin G weekly for 3 weeks is recommended for the treatment

of late latent syphilis and latent syphilis of unknown duration. Limited evidence suggests that treating latent syphilis with a total dose of 7.2 million

U of benzathine penicillin over a 3-week period is curative, even if the patient

has asymptomatic neurosyphilis. However, because of the possible lack of

efficacy of benzathine penicillin G in some patients with CNS syphilis, CSF

examination should be considered in those with latent syphilis to exclude

asymptomatic neurosyphilis, particularly HIV-positive patients, in whom the

prevalence of asymptomatic neurosyphilis is higher. Alternatively, a lumbar

puncture can be performed at the conclusion of the follow-up period

(2 years); if the CSF is normal, the patient can be reassured that neurosyphilis

will not develop.

Larger doses of penicillin are recommended for persons with proven neurosyphilis (see Table 327-4). General paresis responds well to penicillin therapy

if administered early, although progressive neurologic decline may develop

later in as many as a third of treated patients. Carbamazepine in doses of 400

to 800mg/day reportedly treats the lightning pains of tabes dorsalis effectively. Published studies show that a total of 6.0 to 9.0 million U of penicillin G

results in a satisfactory clinical response in approximately 90% of patients with

neurosyphilis who do not have HIV infection. There are anecdotal reports of

increased treatment failures in patients with concomitant HIV infection, and

there is considerable rationale to treat these patients with intravenous penicillin G (20 million U/day for at least 10 days). Therapy for neurosyphilis can result

in increased CSF pleocytosis for 7 to 10 days after starting treatment and may

transiently convert a normal CSF to abnormal.

Although there is no evidence that therapy with antimicrobial drugs is clinically beneficial in patients with cardiovascular syphilis, treatment is recommended to prevent further progression of disease and because approximately

15% of patients with cardiovascular syphilis have associated neurosyphilis. If

patients are allergic to penicillin, it is mandatory that the CSF be examined

before therapy is undertaken; if the CSF is abnormal, desensitization to penicillin is generally recommended. With a normal CSF, tetracycline (500mg orally

four times a day) or doxycycline (100mg orally two times a day) taken for 4

weeks is probably effective.

Because of the risk to the fetus, evaluation and treatment of a pregnant

VDRL-positive patient must be rapid, particularly those first seen in the later

stages of pregnancy. If a confirmatory FTA-ABS test is positive and the patient

has not been treated, penicillin should be administered in doses appropriate

for early or late syphilis, as outlined earlier. For penicillin-allergic patients,

penicillin desensitization is preferred; patients should not be treated with

tetracycline or erythromycin because of toxicity (tetracycline) or lack of efficacy (erythromycin). For patients who are VDRL positive but FTA-ABS negative

and have no clinical signs of syphilis, treatment may be withheld; a quantitative VDRL test and another FTA-ABS test should be repeated in 4 weeks. If

the VDRL titer has risen four-fold or more, or if clinical signs of syphilis have

developed, the patient should be treated. If, after repeat examination, the

diagnosis remains equivocal, the patient should be treated to prevent possible disease in the neonate. After treatment, a quantitative VDRL titer should

be monitored monthly; if it rises four-fold, the patient should be treated a

second time.

Congenital Syphilis

Jarisch-Herxheimer Reactions

Up to 60% of patients with early syphilis and a significant proportion of

patients with later stages of syphilis experience a transient febrile reaction

after therapy for syphilis. The pathogenesis is unclear, but it may be caused by

the liberation of antigens from spirochetes.

This reaction usually occurs in the first few hours after therapy, peaks at 6

to 8 hours, and disappears within 12 to 24 hours of therapy. Occasionally,

Jarisch-Herxheimer reactions are mistaken for allergic reactions to syphilis

therapy. Temperature elevation is usually low grade, and there is often associated myalgia, headache, and malaise. The skin lesions of secondary syphilis are

frequently exacerbated during the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction, and cutaneous lesions that were not visible may become visible. The reaction is generally

of no clinical significance and in most cases can be treated with salicylates.

Corticosteroids have been used to prevent adverse effects of the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction, but there is no evidence that they are clinically beneficial

(other than reducing fever) or necessary. Institution of treatment with small

doses of penicillin does not prevent the reaction.

PREVENTION

All patients with syphilis should be reported to public health authorities. In

the absence of an effective vaccine, control of syphilis depends on finding and

treating persons with infectious lesions of primary and secondary syphilis

before they can transmit the disease, as well as finding and treating individuals with incubating syphilis before infectious lesions develop. All patients

with early syphilis (primary, secondary, or early latent) should be carefully

interviewed by qualified persons to determine the nature of their recent

sexual contacts. Approximately 16% of the named recent contacts of patients

with early syphilis are found to have active, untreated syphilis on examination, and a similar proportion of individuals named as suspects or associates

also have active syphilis.

Treatment of the sexual contacts of patients with early syphilis with 2.4

million U of benzathine penicillin G intramuscularly is recommended even

if the contacts are clinically and serologically normal on examination. This is

because syphilis eventually develops in 30% of clinically normal contacts who

are untreated. In general, preventive treatment is given to all sexual contacts

in the past 90 days, although nearly all cases of syphilis in contacts develop

within 60 days of exposure.

PROGNOSIS

Follow-up Examinations

All HIV-seronegative patients with early or congenital syphilis should return

for quantitative VDRL titers and clinical examination 6 and 12 months after

treatment. For HIV-positive patients, serologic tests should be repeated at 1,

2, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months. Patients with late latent syphilis should also be

examined 24 months after therapy.

In about 85% of patients with early (i.e., primary, secondary, or early latent)

syphilis, quantitative VDRL titers decline two or more dilutions (four-fold)

by 6 and 12 months after therapy. Prolonged reactive VDRL test results are

associated with higher initial VDRL titers, prolonged infection, more

advanced stage (primary < secondary < early latent), or repeated infection.

Chronic, low-titer VDRL reactivity after therapy is much more common in

cases of late syphilis and should not be viewed with alarm. Treponemal tests

may remain positive for years despite adequate therapy. A four-fold or greater

rise in VDRL titer after therapy is sufficient evidence for repeat treatment.

Patients with treated early syphilis are susceptible to reinfection, and many

clinical and serologic relapses after therapy are probably reinfections. As such,

they represent failures of proper epidemiologic case finding and preventive

therapy for the patients sexual contacts.

Patients with neurosyphilis should be monitored with serologic tests for

at least 3 years and with repeat CSF examinations at 6-month intervals. CSF

pleocytosis is the first abnormality to disappear, but cell counts may not be

normal for 1 to 2 years. Elevated CSF protein levels fall even more slowly,

followed by a change in the positive CSF VDRL test, which may take years

to become negative. It is not known whether high-dose intravenous penicillin

therapy accelerates the return of CSF to normal. Rising CSF cell counts,

protein, and VDRL titer obtained at follow-up are an indication for repeat

treatment.

Antibiotic therapy should ultimately cure essentially all patients with early

or secondary syphilis, although treatment failures may occur in patients with

concomitant HIV infection. In tabes dorsalis, penicillin usually arrests progression but does not reverse the symptoms. Meningovascular syphilis generally responds well, except for residual damage resulting from ischemic infarcts.

Visit expertconsult.com for e-expanded chapter

1. Hook EW, Behets F, Van Damme K, et al. A phase III equivalence trial of azithromycin versus benzathine penicillin G for treatment of early syphilis. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:1729-1735.

SUGGESTED READINGS

French P, Gomberg M, Janier M, et al. IUSTI: 2008 European guidelines on the management of syphilis.

Int J STD AIDS. 2009;20:300-309. Consensus guidelines.

Tucker JD, Bu J, Brown LB, et al. Accelerating worldwide syphilis screening through rapid testing: a

systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:381-386. Review of several available rapid tests, with a

focus on the best evaluated immunochromatographic strip test to detect Treponema antibody.

Wolff T, Shelton E, Sessions C, et al. Screening for syphilis infection in pregnant women: evidence for

the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force reaffirmation recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med.

2009; 150:710-716. New evidence to support universal screening of pregnant women for syphilis.

Workowski KA, Berman S; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted

diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59:1-110. National recommendations.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- An. Bras. Dermatol. Vol.81 No.2 Rio de Janeiro Mar./Apr. 2006Documento21 pagineAn. Bras. Dermatol. Vol.81 No.2 Rio de Janeiro Mar./Apr. 2006farah bachmidNessuna valutazione finora

- Syphilis and Otolaryngology: Steven D. Pletcher, MD, Steven W. Cheung, MDDocumento11 pagineSyphilis and Otolaryngology: Steven D. Pletcher, MD, Steven W. Cheung, MDmadhumitha srinivasNessuna valutazione finora

- HHS Public Access: SyphilisDocumento49 pagineHHS Public Access: Syphilisfaty basalamahNessuna valutazione finora

- Toxoplasmosis - A Global ThreatDocumento8 pagineToxoplasmosis - A Global ThreatDr-Sadaqat Ali RaoNessuna valutazione finora

- Treponema Pallidum (Syphilis) - Infectious Disease and Antimicrobial AgentsDocumento14 pagineTreponema Pallidum (Syphilis) - Infectious Disease and Antimicrobial AgentsCarlos DNessuna valutazione finora

- TUBERCULOSIS Imaging ManifestationsDocumento21 pagineTUBERCULOSIS Imaging ManifestationsEdgard Eduardo Azañero EstradaNessuna valutazione finora

- ChlamydiaDocumento13 pagineChlamydiaTitus MutwiriNessuna valutazione finora

- Sexually Transmited InfectionsDocumento12 pagineSexually Transmited InfectionsjazbethNessuna valutazione finora

- Key Infections in The PlacentaDocumento14 pagineKey Infections in The PlacentaLauraGonzalezNessuna valutazione finora

- The Immune Response To Infection With Treponema Pallidum, The Stealth PathogenDocumento8 pagineThe Immune Response To Infection With Treponema Pallidum, The Stealth Pathogenhazem alzedNessuna valutazione finora

- AgingDocumento8 pagineAgingEszter BándiNessuna valutazione finora

- Lection 8 SyphilisDocumento39 pagineLection 8 SyphilisAtawna AtefNessuna valutazione finora

- TuberculosisDocumento4 pagineTuberculosisDr Mangesti Utami PKM Kebaman BanyuwangiNessuna valutazione finora

- Although Other Organs Are Involved in Up To One-Third of Cases. If Properly Treated, TB Caused by Drug-Susceptible Disease May Be Fatal Within 5 Years in 50-65% of CasesDocumento69 pagineAlthough Other Organs Are Involved in Up To One-Third of Cases. If Properly Treated, TB Caused by Drug-Susceptible Disease May Be Fatal Within 5 Years in 50-65% of Casesnathan asfahaNessuna valutazione finora

- Tuberculosis - Disease Management - CompDocumento17 pagineTuberculosis - Disease Management - CompAhsan kamalNessuna valutazione finora

- CHN Report GoyetaDocumento24 pagineCHN Report GoyetaMezil NazarenoNessuna valutazione finora

- Tuberculosis: Tuberculosis, MTB, or TB (Short For TubercleDocumento12 pagineTuberculosis: Tuberculosis, MTB, or TB (Short For TubercleRoxana BerceaNessuna valutazione finora

- SPIROCHETES (Treponema, Borrelia and Leptospira)Documento4 pagineSPIROCHETES (Treponema, Borrelia and Leptospira)Muneer Al-DahbaliNessuna valutazione finora

- Tuberculosis - Natural History, Microbiology, and Pathogenesis - UpToDateDocumento20 pagineTuberculosis - Natural History, Microbiology, and Pathogenesis - UpToDateandreaNessuna valutazione finora

- Diagnosis of Syphilis Ref Best PDFDocumento27 pagineDiagnosis of Syphilis Ref Best PDFLavina D'costaNessuna valutazione finora

- Syphilis: Castro, Khristine Marie Laudencia BSNDocumento8 pagineSyphilis: Castro, Khristine Marie Laudencia BSNPlan Can JoxNessuna valutazione finora

- Infectious Disease Chapter Five Mycobacterial DiseasesDocumento47 pagineInfectious Disease Chapter Five Mycobacterial DiseasesHasrul RosliNessuna valutazione finora

- 2013 Yaws Seminar LancetDocumento11 pagine2013 Yaws Seminar LancetOlivia Halim KumalaNessuna valutazione finora

- 06 Neurocisticercosis Actualidad y AvancesDocumento7 pagine06 Neurocisticercosis Actualidad y Avancesfeliecheverria11Nessuna valutazione finora

- Articulo de Ingles de LadyDocumento36 pagineArticulo de Ingles de LadyLina Marcela Quintero VargasNessuna valutazione finora

- CASE 32 STI (Sexually Transmitted Infection)Documento29 pagineCASE 32 STI (Sexually Transmitted Infection)abdulwahab ibn hajibushraNessuna valutazione finora

- Hospital General Docente de Calderón Internal Medicine: Clinical Academy Project Topic ReviewDocumento26 pagineHospital General Docente de Calderón Internal Medicine: Clinical Academy Project Topic Reviewdani_zurita_1Nessuna valutazione finora

- 1.1 Viral Diseases Jocelyn Fernández VelascoDocumento2 pagine1.1 Viral Diseases Jocelyn Fernández VelascoFERNANDEZ VELASCO JOCELYNNessuna valutazione finora

- Types of Sexually Transmitted InfectionsDocumento4 pagineTypes of Sexually Transmitted InfectionsWarren ConsultaNessuna valutazione finora

- Typhoid FeverDocumento14 pagineTyphoid FeverJames Cojab SacalNessuna valutazione finora

- General Information About Meningococcal DiseaseDocumento14 pagineGeneral Information About Meningococcal DiseaseBrijesh Singh YadavNessuna valutazione finora

- MeningococcemiaDocumento14 pagineMeningococcemiaMonica Marie MoralesNessuna valutazione finora

- Blastomycosis: University of Toronto Medical Journal January 2004Documento5 pagineBlastomycosis: University of Toronto Medical Journal January 2004AlternaNessuna valutazione finora

- Background: Toxoplasma Gondii. Cats Are The Primary Hosts, While Humans and Other Mammals Serve AsDocumento13 pagineBackground: Toxoplasma Gondii. Cats Are The Primary Hosts, While Humans and Other Mammals Serve AsMelly AfriyatiNessuna valutazione finora

- RB - Petersen. Toxoplasmosis, UpToDate, 2019Documento12 pagineRB - Petersen. Toxoplasmosis, UpToDate, 2019GuilhermeNessuna valutazione finora

- Infectious Tuberculosis-18 (Muhadharaty)Documento11 pagineInfectious Tuberculosis-18 (Muhadharaty)dr.salam.hassaniNessuna valutazione finora

- PlagueDocumento20 paginePlagueHemanth G.Nessuna valutazione finora

- CS TBDocumento16 pagineCS TB025 MUHAMAD HAZIQ BIN AHMAD AZMANNessuna valutazione finora

- Toxoplasmosis Revisited: Sheela Mathew, MD, Infectious Diseases Department, GovernmentDocumento11 pagineToxoplasmosis Revisited: Sheela Mathew, MD, Infectious Diseases Department, GovernmentMuhammad Afiq HusinNessuna valutazione finora

- Typhoid FeverDocumento13 pagineTyphoid FeverFajar NarakusumaNessuna valutazione finora

- Tuberculosis: BackgroundDocumento25 pagineTuberculosis: BackgroundLuis Alberto Basurto RomeroNessuna valutazione finora

- Assignment: - TuberculosisDocumento9 pagineAssignment: - TuberculosisAakash SahaNessuna valutazione finora

- A Review On The Diagnosis and Treatment of SyphiliDocumento8 pagineA Review On The Diagnosis and Treatment of SyphiliRaffaharianggaraNessuna valutazione finora

- Infeksi StreptoDocumento6 pagineInfeksi StreptoRiris SutrisnoNessuna valutazione finora

- CDC 48172 DS1Documento15 pagineCDC 48172 DS1Novelina Fatima SoaresNessuna valutazione finora

- Tuberculosis, MTB, or TB (Short For TubercleDocumento22 pagineTuberculosis, MTB, or TB (Short For TubercleKriti AgrawalNessuna valutazione finora

- TB PaperDocumento11 pagineTB PapergwapingMDNessuna valutazione finora

- MeningDocumento12 pagineMeningmulyadiNessuna valutazione finora

- tmpF7DD TMPDocumento6 paginetmpF7DD TMPFrontiersNessuna valutazione finora

- Toxoplasma GondiiDocumento7 pagineToxoplasma Gondiiأحمد المسيريNessuna valutazione finora

- PAEDS 3 - 15.10.19 PneumoniaDocumento10 paginePAEDS 3 - 15.10.19 Pneumonialotp12Nessuna valutazione finora

- SYPHILISDocumento5 pagineSYPHILISjoshua tauroNessuna valutazione finora

- Current Status of Leprosy: Epidemiology, Basic Science and Clinical PerspectivesDocumento9 pagineCurrent Status of Leprosy: Epidemiology, Basic Science and Clinical PerspectivesYolan Sentika NovaldiNessuna valutazione finora

- Tuverculosis in OlderDocumento13 pagineTuverculosis in OlderjcarloscangalayaNessuna valutazione finora

- Prevention and Treatment of Mother-To-Child Transmission of SyphilisDocumento7 paginePrevention and Treatment of Mother-To-Child Transmission of SyphilisRocky.84Nessuna valutazione finora

- 2020 Epidermic and Endermic DiseasesDocumento5 pagine2020 Epidermic and Endermic DiseasesOluwakemi OLATUNJI-ADEWUNMINessuna valutazione finora

- Tuberculous Spondylodiscitis: Epidemiology, Clinical Features, Treatment, and OutcomeDocumento15 pagineTuberculous Spondylodiscitis: Epidemiology, Clinical Features, Treatment, and OutcomeC-Bianca EmiliaNessuna valutazione finora

- TUBERCULOSISDocumento8 pagineTUBERCULOSISMariam SheebaNessuna valutazione finora

- Surgical Nutrition: Vic V.Vernenkar, D.O. St. Barnabas Hospital Dept. of SurgeryDocumento54 pagineSurgical Nutrition: Vic V.Vernenkar, D.O. St. Barnabas Hospital Dept. of SurgeryAmir SharifNessuna valutazione finora

- Caregiving NC II - CBCDocumento126 pagineCaregiving NC II - CBCDarwin Dionisio ClementeNessuna valutazione finora

- DOH DILG Joint AO 2020-0001 On LIGTAS COVID and Community-Based Management of COVID-19Documento44 pagineDOH DILG Joint AO 2020-0001 On LIGTAS COVID and Community-Based Management of COVID-19Albert DomingoNessuna valutazione finora

- Increasing Height Through Diet, Exercise and Lifestyle AdjustmentDocumento2 pagineIncreasing Height Through Diet, Exercise and Lifestyle AdjustmentEric KalavakuriNessuna valutazione finora

- Colostrum - How Does It Keep Health?Documento9 pagineColostrum - How Does It Keep Health?JakirNessuna valutazione finora

- Propaira - NCI Apr 2012 FINAL v1.0Documento2 paginePropaira - NCI Apr 2012 FINAL v1.0Mustafa TurabiNessuna valutazione finora

- 5th Ed WHO 2022 HematolymphoidDocumento29 pagine5th Ed WHO 2022 Hematolymphoids_duttNessuna valutazione finora

- Inca and Pre-Inca MedicineDocumento6 pagineInca and Pre-Inca MedicineVALERIA BORJA GIONTINessuna valutazione finora

- Research PaperDocumento10 pagineResearch PaperAyyat FatimaNessuna valutazione finora

- Vaccines and Medicines of Pets in PakistanDocumento7 pagineVaccines and Medicines of Pets in PakistanTress Lavena100% (1)

- CURRICULUM VITAE Netra June 2017Documento10 pagineCURRICULUM VITAE Netra June 2017Minerva Medical Treatment Pvt LtdNessuna valutazione finora

- 3a. Antisocial Personality DisorderDocumento19 pagine3a. Antisocial Personality DisorderspartanNessuna valutazione finora

- Behavioral Skill TrainingDocumento28 pagineBehavioral Skill TrainingEttore CarloNessuna valutazione finora

- Professional Disclosure StatementDocumento2 pagineProfessional Disclosure Statementapi-323266047Nessuna valutazione finora

- Zimmerman 2013 Resiliency Theory A Strengths Based Approach To Research and Practice For Adolescent HealthDocumento3 pagineZimmerman 2013 Resiliency Theory A Strengths Based Approach To Research and Practice For Adolescent HealthCeline RamosNessuna valutazione finora

- MSDS Addmix 700Documento6 pagineMSDS Addmix 700Sam WitwickyNessuna valutazione finora

- Safety Data Sheet: 1. Identification of The Substance/Preparation and of The Company/UndertakingDocumento6 pagineSafety Data Sheet: 1. Identification of The Substance/Preparation and of The Company/UndertakingJulion2009Nessuna valutazione finora

- Succus Liquiritiae PLV.: Material Safety Data SheetDocumento3 pagineSuccus Liquiritiae PLV.: Material Safety Data SheetTifany Putri SaharaNessuna valutazione finora

- Urine Elmination Concept Map PDFDocumento1 paginaUrine Elmination Concept Map PDFRichard RLNessuna valutazione finora

- Acute Herpetic Gingivostomatitis Associated With Herpes Simplex Virus 2Documento4 pagineAcute Herpetic Gingivostomatitis Associated With Herpes Simplex Virus 2Ayu KartikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Certificate IV in Commercial Cookery Sit 40516Documento8 pagineCertificate IV in Commercial Cookery Sit 40516Tikaram GhimireNessuna valutazione finora

- Hydrochlorothiazide Versus Chlorthalidone: Brief ReviewDocumento6 pagineHydrochlorothiazide Versus Chlorthalidone: Brief ReviewKrishna PrasadNessuna valutazione finora

- Canadas Food Guide Serving SizesDocumento2 pagineCanadas Food Guide Serving SizesVictor EstradaNessuna valutazione finora

- Chronic Low Back Pain Good Clinical Practice GCPDocumento341 pagineChronic Low Back Pain Good Clinical Practice GCPTru ManNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson 2 Progression and OverloadDocumento2 pagineLesson 2 Progression and OverloadisaiacNessuna valutazione finora

- Burn WoundsDocumento14 pagineBurn WoundsRuxandra BadiuNessuna valutazione finora

- IEC Submission FormDocumento10 pagineIEC Submission FormAbhishek YadavNessuna valutazione finora

- Doctors Progress Note - Module 5Documento4 pagineDoctors Progress Note - Module 5adrian nakilaNessuna valutazione finora

- VIVA PresentationDocumento26 pagineVIVA PresentationWgr SampathNessuna valutazione finora

- Burnout and Self-Care in SWDocumento12 pagineBurnout and Self-Care in SWPaul LinNessuna valutazione finora