Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Military Orientalism (

Caricato da

Anonymous QvdxO5XTRTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Military Orientalism (

Caricato da

Anonymous QvdxO5XTRCopyright:

Formati disponibili

This article was downloaded by: [King's College London]

On: 04 November 2013, At: 08:17

Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954

Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH,

UK

Journal of Strategic Studies

Publication details, including instructions for authors

and subscription information:

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fjss20

Book Reviews

a

F. G. Hoffman , John Bew , David French , Nicolas

d

Lewkowicz , Thomas Rid , Paul Staniland , Tim

g

Stevens & Peter J. P. Krause

a

Fairfax Station , VA

King's College London

Brentwood , Essex

University of Bristol

The Shalem Center , Jerusalem, Israel

University of Chicago

King's College London

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Published online: 21 Oct 2010.

To cite this article: F. G. Hoffman , John Bew , David French , Nicolas Lewkowicz ,

Thomas Rid , Paul Staniland , Tim Stevens & Peter J. P. Krause (2010) Book Reviews,

Journal of Strategic Studies, 33:5, 777-795, DOI: 10.1080/01402390.2010.513199

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2010.513199

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the

information (the Content) contained in the publications on our platform.

However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no

representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or

suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed

in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the

views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should

not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources

of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions,

claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities

whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection

with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content.

Downloaded by [King's College London] at 08:17 04 November 2013

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes.

Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sublicensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly

forbidden. Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://

www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

The Journal of Strategic Studies

Vol. 33, No. 5, 777795, October 2010

BOOK REVIEWS

Downloaded by [King's College London] at 08:17 04 November 2013

Donald Kagan, Thucydides: The Reinvention of History. New York:

Viking, 2009. Pp. 257. $26.95, PB. ISBN 9-780-14311-829-9.

No one can fault Thucydides for lack of ambition. It will be enough for

me, he wrote nearly 25 centuries ago, if these words of mine are

judged useful by those who want to understand clearly the events which

happened in the past and which (human nature being what it is)

will . . . be repeated in the future. In a massive narrative covering

notable examples of Greek hubris, the Athenian author sought to

produce a possession for all time. While Thucydides might be accused

of arrogance, he did achieve his goal. Human nature being what it is,

the interplay of fear, honor and interest in human conflict has been

continuously repeated. His History of the Peloponnesian War remains

a classic text and has rightly earned him accolades as the father of

political history. Thucydides called war a savage schoolmaster, and he

effectively addressed the role of strategic assessment, the importance of

domestic politics in conflict, the complexities of alliances and

diplomacy, and the interplay of land and sea warfare.

For this reason, Thucydides sits on a pedestal among historians, and

his work is considered de rigueur today for anyone serious about

military history and international relations. His insights have proven

invaluable to serious students attempting to understand the past and

apply it to the present and future. Much of this reputation is based on

Thucydides purportedly dispassionate style, attention to detail, and

perceived objectivity. Comparing him to Herodotus, the author Robert

Kaplan observes, Thucydides is more trustworthy. He is also more

limited. Thucydides gives us a distilled rendition of the facts. Likewise,

Princetons James McPherson prefers Thucydides precisely because he

is a more careful, precise, and trustworthy historian who does not try to

go beyond the evidence.

Yet, as the distinguished Yale classicist Donald Kagan shows in

Thucydides: The Reinvention of History, our Athenian narrator is not

quite the detached historian we were led to think. After he was exiled as

a disgraced Athenian admiral for the embarrassing loss of Amphipolis

in 424 BC, Thucydides had much time to ponder the war. However, he

was also biased by his association with critical players like Pericles and

his preference for the propertied class. Like any historian, Thucydides

ISSN 0140-2390 Print/ISSN 1743-937X Online/10/050777-19

DOI: 10.1080/01402390.2010.513199

Downloaded by [King's College London] at 08:17 04 November 2013

778 Book Reviews

had to create a framework for the war and had to select facts and weigh

sources and arrange a narrative. His History is very much a personal

history with honor and reputation at stake. Contrary to what we might

have thought, Thucydides is more subtle than trustworthy. Like

Winston Churchill, he carefully crafted a story he wanted the audience

to accept. As Kagan reveals in his wonderfully handled account,

Thucydides was human after all and his account should be treated with

some skepticism. The author of his own highly regarded four-volume

history of the ancient Greeks own Long War, Kagan meticulously

weighs the evidence from other sources of that time as well as

Thucydides own account.

Thus, while Thucydides paints Pericles and his grand strategy for the

war as completely reasonable, Kagan finds this to be a revisionist

interpretation. Blame for the protracted and plague-ridden strife of

Athens was laid at the feet of the fickle nature of democratic rule by the

Athenian historian. No mention is made of Pericles failure to ensure

that the Athenian treasury was robust enough to make the strategy

viable or whether his defensive strategy fitted Greek culture.

Likewise, Thucydides would have his readers believe that the

infamous Sicilian expedition in 415 (and the next years surge) should

not be blamed on the aristocratic Nicias. Again no mention is made of

Nicias own failures to ensure that his expedition was equipped with

the cavalry required to take Syracuse, or his poor tactical dispositions

and weak leadership. Kagan convincingly demonstrates that Thucydides shades his arguments, largely by omission, to craft his own

interpretation of events against the contemporary accounts of his time.

While generous with praise for the Athenians research, Professor

Kagan finds that For all his unprecedented efforts to seek and test the

evidence, and for all his originality and wisdom, he was not infallible.

While not the perfect picture of detachment his admirers thought

him to be, Kagan has no problem arguing that the study of Thucydides

text still merits our time. As he concludes: His History raises for the

first time countless questions about the development of human societies

that remain very relevant today. He looks deeply into the causes of war,

drawing a distinction between those openly alleged and those more

fundamental but less obvious. Kagan continuously demonstrates a

mastery of his subject matter and the broader context of the age.

Anyone who wants to understand Thucydides in breadth, depth and

context should read Kagans discerning deconstruction of the underlying evidence. The author dissects the arguments embedded in the

History of the Peloponnesian War with exquisite detail and scholarship. The end product is a masterful work of history that will assuredly

be judged as an indispensable commentary, highly recommended for all

graduate-level courses in history and international security studies or

Book Reviews 779

for anyone wanting to understand why the past will be repeated in the

future.

F. G. HOFFMAN 2010

Fairfax Station, VA

Downloaded by [King's College London] at 08:17 04 November 2013

Jeremy Black, The Battle of Waterloo: A New History. London: Icon

Books, 2010. Pp. 220. 14.99, PB. ISBN 9-781-84831-155-8.

Both experts and amateur enthusiasts will be interested in the latest

offering from one of Britains foremost and most prolific military

historians, though this book is more clearly geared to the latter.

Professor Jeremy Black offers a fresh perspective on the Battle of

Waterloo of 1815, by emphasising the importance of the long-term

military, political, geopolitical and strategic context in which it took

place. In doing so, he provides a counterpoint to those historians who

see the impact of Napoleon and his vast conscript army as a military

revolution to go alongside the political revolution which began in Paris

in 1789. Instead, Black believes that Waterloo in common with much

of the history of the so-called revolutionary period testifies to the

resilience of ancien regime ideas, structures, societies, and solutions,

including military means. If anything, he argues, the potential for

change was best represented not by Napoleon, whose Caesarism made

him essentially a destructive force, but by the capability of the

impersonal state in the shape of Britain, headed (though not led) by the

elderly, deaf, blind and mentally unstable George III.

The book is, in essence, a synthesis of the most recent secondary

literature on Waterloo, so readers expecting to find fresh archival

research will be disappointed. Much of the ground which is covered

will also be familiar to professional historians of this period. For

example, Black spends a significant amount of time explaining

Napoleons preference for concentrating his resources and attentions

on a single front at one time and his avoidance of lengthy, sapping

campaigns in favour of decisive set-piece battles. The same might be

said of the observation that Britain and Russia were the biggest winners

from the post-war settlement, or the section which deals with Frances

return to the international system after 1815.

Nonetheless, the obvious and admirable attempt to address a wider

audience does not distract from the underlying quality of analysis.

Black navigates the work of other historians with eloquence and brio,

and a refreshing lightness of touch. At most junctures, he emphasises

the existence of continuity over change and the accidental (or

circumstantial) ahead of individual genius. This is not simply a case

Downloaded by [King's College London] at 08:17 04 November 2013

780 Book Reviews

of the revenge of the particular on the general so much as an attempt to

restore complexity where simplistic narratives have taken over.

While steering clear of mystical readings of his strengths, his

chapter on Napoleons generalship is accessible, balanced and

judicious. Likewise, his account of the Peninsular War more

particularly the lessons that Wellington learned from it and applied

at Waterloo is also impressive and useful to scholars of any level.

When it comes to Waterloo itself, we are left with a vivid picture of the

chaotic as much as the heroic reality of the battle: the uncommon level

of hand-to-hand combat; the poor visibility because of the huge

clouds of gunfire smoke which filled the air; the poor communication

between officers due to mounted couriers regularly falling off their

horses, often to their deaths; and the high rate of casualties from

backfiring cannons.

It is in the last few chapters where Black opens himself to consider

the wider impact of Waterloo on domestic politics, geopolitics and

diplomacy that he makes some of his most interesting and original

observations, but also veers slightly off script. There are one or two

instances in which the tone becomes unnecessarily polemical: such as

his complaint about what he sees as an attempt to de-militarise

military history in academia or more tangentially a condemnation

of New Labours attitude to history in contrast with Margaret

Thatchers robust historicized nationalism. Similarly, while the overall

emphasis on continuity is convincing, it is not quite accurate to say that

the European great-power system did not change substantially for

several decades; the Treaty of Vienna was a watershed in international

relations and, of course, most of its provisions were agreed before

Napoleon escaped from Elba.

Waterloo is often accredited with creating the assumption that one

great set-piece battle could settle a war something which subsequent

wars, from the Crimean to World War II, spectacularly disproved.

Towards the end of the essay, Black makes the point that the

Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars the lessons of which shaped

military strategy through much of the nineteenth and twentieth

centuries are also seen as less worthy of study in a modern era of

insurrectionary and counter-insurrectionary warfare. In fact, as he

points out, such tactics were a crucial facet of the great power warfare

from 1792 to 1815, particularly the guerrilla warfare which occurred

on the Spanish Peninsula. Unfortunately, the author does not expand

on the insight any further, but contemporary military strategists could

do worse than turn their attention to this period.

JOHN BEW 2010

Kings College London

Book Reviews 781

Downloaded by [King's College London] at 08:17 04 November 2013

William Philpott, Bloody Victory: The Sacrifice of the Somme and the

Making of the Twentieth Century. London: Little Brown, 2009.

Pp.699. 25.00, HB. ISBN 978-1-4087-0108-9.

The Battle of the Somme in 1916 was the biggest and most expensive

battle ever fought by the British Army. Stupid and callous generals

mismanaged operations on a grand scale in the course of a pointless

battle that condemned a whole generation of young Britons to their

deaths. These are the accepted cliches that have left a scar on the British

national psyche that remains to this day. They are why most of the

Anglophone literature on the battle focuses entirely on the British

experience.

But Bill Philpotts starting point is that such a narrow reading of

the past cannot make sense of the battle because it fails to

comprehend the bigger picture. Basing his conclusions not merely

on British, but also on Canadian, Australian, French and German

archival sources, it is that bigger picture that he presents here. It takes

two sides to make a battle, and what is important about this book is

that it integrates the operations of both Britains major ally, the

French, and their common enemy, the Germans, into the story. In

doing so Bloody Victory goes a long way towards transforming the

time-honoured narrative.

Philpotts assessment of the British experience on the Somme reflects,

and builds upon, the modern scholarly consensus, albeit one that has

hardly penetrated the popular consciousness. This was a war between

industrial empires, and it inevitably degenerated into an attritional

struggle. Casualties were bound to be grievously high. The British

Armys losses on 1 July 1916 were excessive. The infantry were sent

over the top to achieve over-ambitious objectives with too little artillery

support. But thereafter the British Army began to learn valuable

lessons. By September, its professional skills had improved and its rate

of losses had dropped. But what is less well-understood, even by

scholars, is that the Somme was not a British, but an Anglo-French

offensive. The battle was just one part of a bigger Entente strategy. The

French committed about the same number of troops to the battle as

the British, but thanks to their greater professionalism from the start of

the battle they suffered significantly fewer casualties in their operations

south of the river.

If the book has a hero it is the French commander, Ferdinand Foch.

Recognising that a breakthrough was impossible, by September 1916

Foch had begun to develop a new operational art form, the bataille

generale. Combining high tempo operations, material superiority,

manoeuvre and an attritional strategy, he showed that by knocking the

Germans off-balance it was at least possible to push them backwards.

Downloaded by [King's College London] at 08:17 04 November 2013

782 Book Reviews

When he practised it on a much grander scale as the Allied

generalissimo during the Hundred Days campaign in 1918, it was

this doctrine that was finally to shatter the cohesion of the German

Army.

But that cohesion had already suffered a grievous blow on the

Somme. If both the French and British lost heavily in the summer of

1916, the biggest losers in Philpotts estimation, were the Germans.

Coming on top of their casualties at Verdun, by the end of the battle the

Germans had lost about a million men on the Western Front in the

course of 1916. In the authors stark, but realistic, assessment,

industrial war in the early twentieth century was not about controlling

territory; it was concerned with deploying machines to kill men. By the

end of the battle the Germans soldiers determination to fight on to final

victory at whatever the cost was starting to crack.

The book also goes beyond the battlefield to examine how the battle

was interpreted and understood on the home fronts of the belligerents.

This enables Philpott to provide a compelling critique of the myth that

the battle was futile. It did not seem futile either to the men who fought

it or their families back home. The Somme pitted not just armies

against each other, but opposing political and cultural systems. It was a

struggle between parliamentary democracy, in its French and British

forms, versus authoritarian German kultur. It was just as much a

psychological and political struggle as it was a military battle of

attrition.

It does the memory of those who died during the battle a grave

disservice to suggest that they did not die for a good cause. The British

believed they were fighting to crush the evils of Prussian militarism. The

French were determined to liberate their occupied provinces from the

German yoke. The Germans were fighting to defend their beleaguered

empire. Everyone knew that they had right on their side. Today these

might not seem like ideas worth dying for. But our inability to grasp the

fact that they did seem like supremely good causes to soldiers and

civilians in 1916 shows how far removed we are from the world of our

grandfathers and great-grandfathers.

DAVID FRENCH 2010

Brentwood, Essex

Giles MacDonogh, 1938: Hitlers Gamble. London: Constable, 2009.

20.00, HB. ISBN 9-781-84529-845-6.

This book chronicles the eventful year of 1938, starting with a review

of Hitlers strategic plans, as revealed in the Hossbach minutes of the

Downloaded by [King's College London] at 08:17 04 November 2013

Book Reviews 783

meeting summoned by Hitler in November 1937. The Hossbach

memorandum, which became an important piece of evidence at the

Nuremberg Trials, outlined Hitlers aims for the future of the

Reich. Hitlers blueprint called for the preservation and enlargement

of the German racial community, not overseas, but in Europe.

The Reichs territorial expansion would provide the German nation

with the required Lebensraum to achieve economic self-sufficiency.

This required the annexation of Austria and Czechoslovakia and

the extraction of their much needed manpower, foreign currency

and raw materials in order to entrench Germanys geostrategic

position.

MacDonogh points out that it seems unlikely . . . that Hitler had a

master plan for these changes or any grand strategy that was specific to

1938 (pp.xixxx). The author highlights that by 1938 the conservative

elements in the Hitlerite regime had become increasingly marginalised

after verbalising their disagreement at the revisionist drive which was

crippling the German economy. Hermann Goring had replaced

Hjalmar Schacht as the Nazi economics supremo and was put in

charge of making Germany self-sufficient while financing rearmament.

At the same time, the German foreign policy apparatus had suffered

irreversible changes with Foreign Minister Constantin von Neurath and

several key ambassadors having been replaced.

A chapter is devoted to each month of that momentous year, charting

the events which precipitated the war. MacDonogh cites the Blomberg

Fritsch crisis in January and the end of Cabinet government in

February, which solidified Hitlers position and isolated the moderate

elements in the regime. The Anschluss in March, the Austrian Plebiscite

in April that revealed overwhelming support for the Fuhrer (p.xv),

Hitlers trip to Rome in May, which consolidated the alliance with

Italy, and the Kendrick crisis in August which destroyed the British

intelligence network in Germany are also given extensive treatment.

The strategic situation would take a decisive turn with Neville

Chamberlains visit to Germany and the signing of the Munich

agreement in September, the occupation of the Sudetenland in October

and the persecution of the Jews in the latter part of the year.

Hitlers trip to Italy revealed the ambivalent position of Mussolini

and his entourage towards Nazi Germany. While Hitler proved willing

to relinquish any claims to the South Tyrol in return for freedom of

movement in Austria and Czechoslovakia (p. 131), Ribbentrop was

anxious to link Italy into a pact with Germany. Despite acquiescing to

the adoption of the racial laws against the Jews, the Fascist leadership

were apprehensive about joining such a treaty, as they intended to

honour the 1937 Anglo-Italian Agreement which gave validity to

Romes claims in the Mediterranean.

Downloaded by [King's College London] at 08:17 04 November 2013

784 Book Reviews

MacDonogh mentions that the signing of the Munich Agreement in

September obliterated any chances to remove Hitler from power

because of opposition in the army and the Wilhelmstrasse and the

reaction against Canaris and Kleist-Schmenzin and all those who had

implied that Britain would fight (p.228). The Munich Agreement

entailed the weakening of the internal opposition to Hitler. Consequently, there would be no further major attempts to undermine the

Fuhrers authority until the failed coup of 20 July 1944.

The book pays particular attention to the plight which befell the

Jewish population in Austria after the Anschluss, something which

became the first statement of intent in Hitlers desire for a Judenrein

Europe. The author points out that the annexation of Austria provided

Hitler with the opportunity to implement the eradication of Jewish life

by means of emigration, the plundering of Jewish businesses and,

remarkably, through an end to assimilation (p.116).

The author works on the premise that until 1938, Hitler could be

dismissed as a ruthless but efficient dictator, a problem to Germany

alone; after 1938 he was clearly a threat to the entire world.

MacDonogh succeeds in mapping the most relevant indicators of

Hitlers strategy and the events that were to plague the continent of

Europe a year later. Although somewhat broadly tackled, it constitutes

a revealing account of Hitlers opening moves to war.

NICOLAS LEWKOWICZ 2010

University of Bristol

Patrick Porter, Military Orientalism: Eastern War Through Western

Eyes. New York: Columbia University Press, 2009. Pp.256. $25.00,

HB. ISBN 978-0-231-15414-7.

The orient is a diffuse idea. Oriental was what lurked beyond the

boundaries of civilised Europe, unknown and fascinating. It stood for

the East, sometimes for the South, always for the unknown other. Ideas

of the oriental other have not just influenced, and sometimes

dominated, Western perspectives toward the East. As Patrick Porters

fine new book shows, orientalism has also affected Western views of its

battles and wars.

On the face of it, the scene is predictable: Western armies are made

for industrial battles, decisive plots of organised force, and orchestrated

manoeuvres. They are rational, orderly, calculated bureaucracies with a

sophisticated division of labour, high-tech weapons systems and clear

lines of authority from civilian politicians. They develop plans in

institutionalised general staffs, and their strategic and operational

Downloaded by [King's College London] at 08:17 04 November 2013

Book Reviews 785

thinking guided by post-Enlightenment intellectual craftsmen like

Antoine de Jomini or Carl von Clausewitz.

Easterners, so the popular stereotype goes, fight altogether differently

as martyrs and kamikazes. They are deceitful, cunning, irrational,

emotional, chaotic, and spiritual, their raw violence seemingly triggered

by primordial ethnic or tribal hatred, vendettas, and blood feuds. Some

of these juxtapositions are very much alive today. Patrick Porter sees

the orientalist world view come to the fore in popular culture, for

instance in films like 300, Black Hawk Down, Rambo II and III, and

The Last Samurai. But such an argument would be trite. Military

Orientalism is shrewder.

Porters critical thrust goes against the cultural turn, the revived

focus on culture among those who make and study strategy. The United

States land forces have turned their attention to understanding alien

cultures counter-insurgencys human terrain and away from the

high-tech hype of the 1990s. Europes armies, with the usual delay of a

few years, are chasing after what some critics see as an American fad. In

academia and strategic studies, likewise, anthropologists and counterinsurgency theory is in; Clausewitz is out. Yes, seeing the relevance of

culture is a step forward, Porter agrees. But seeing culture as rigid and

stable can be naive.

Instead, Military Orientalism analyses culture in motion. The

books objective is to marry better models of culture with the world of

military policy and analysis. The thesis is radical only at first glance: in

strategy, where all sides in a conflict apply almost all means at their

disposal to succeed, culture becomes more dynamic and more volatile.

When facing battle, actors change traditions, violate norms, and they

innovate in order to gain an advantage. At war, Porter writes, even

actors regarded as conservatives may use their culture strategically,

remaking their worlds to fit their needs. Culture does not just shape

ways of war; war shapes culture.

Four chapter-length case studies furnish the argument.

The first deals with British military observers of the Russo-Japanese

War of 190405, who linked Japans prowess to its social setup,

political values, and concept of citizenship. Yet British observers

claimed that the Japanese way of war and the Far Eastern warrior

values offered advice that could help improve the British Empires

mastery of battle, as Britains own fighting ethos was diluted by

urbanisation, modernisation, and liberalism.

The second case study explores Western perceptions of Mongol

warriors, who roamed Central Asias endless steppe in the first half of

the thirteenth century. European and American observers came to see

Genghis Khans mounted warriors as roaming nomadic predators,

laying waste to civilisation on its path with chilling virtuosity. But the

Downloaded by [King's College London] at 08:17 04 November 2013

786 Book Reviews

Mongols mobility and aggressiveness, in turn, have long inspired

European, Russian, and lately American strategic thinkers.

Then Porter moves on to more recent examples, the Taliban and

Hizballah. Both enemies have in common that they are cultural

realists they may change long-established behaviour, their timehonoured traditions, and their accustomed cultural dispositions in

order to fit their strategic and operational needs, to guarantee survival

if not success on the twenty-first-century battlefield. The Taliban, he

argues, therefore exhibit a characteristic ambiguity between stasis and

change. At first glance, the Islamist purists appear as tribal warriors,

driven by extreme and extremely conservative values and

worldviews. Yet, at closer view, the Taliban are highly adaptive

enemies, with innovative methods in education, public outreach, and

modern tactics that embrace the latest high-tech innovations.

The book focuses on two issues simultaneously, Western views and

Eastern war on both counts Military Orientalism has some

shortcomings. It somewhat selectively uncovers orientalist attitudes

in scholarly articles and policy documents. As a result, the book

sometimes seems to overestimate the strategic relevance of perceptions,

including oriental perceptions. The Second Lebanon War (2006), for

instance, was highly damaging for Hizballah, no matter its short-term

public relations advantage in some quarters.

Second, the books criticism of cultural notions is right most of the

time, but not all the time. The remarkable increase in suicide bombings,

to give just one example, is hard to explain without reference to

spirituality and features that seem genuine to specific cultures.

Orientalist views, in short, may sometimes be wrong and irrelevant,

but sometimes they may be correct and relevant. But the author

recognises these problems and admits that his book may be tinged by

the very images and myths that it seeks to challenge.

Politicians view the armed forces as instruments of state power.

Armies often see themselves as surgeons, methodically administering a

certain treatment until an operation is accomplished successfully. Both

like to imagine the enemy as still, pliable, and visible. In Porters

potent analysis, reality is not as neatly cut and stable. The most

endurable element may be the Western views of its oriental enemies.

Here, Porters notion of cultural realism is designed to create better

strategic visibility: attention to cultural fluidity, to contradictions, and

to our own assumptions, he hopes, may help realise, for instance, how

the Taliban of today differ from the Taliban of 2001, or how

Hizballahs tactics have changed between 2000 and 2006.

War, Porter writes in Clausewitzian fashion, is a deadly

reactive dance, and culture is subject to its volatile nature. The

cultural landscape cannot be accurately mapped with the help of

Book Reviews 787

anthropologists, because that human terrain, unlike geography, is ever

shifting. Herein lies the danger of the cultural turn in strategic affairs: it

is not just that it may restate old bigotry in the language of political

correctness. It may ignore and deny something much older and much

more fundamental: the dynamic nature of war.

Downloaded by [King's College London] at 08:17 04 November 2013

THOMAS RID 2010

The Shalem Center, Jerusalem, Israel

Steven R. David, Catastrophic Consequences: Civil Wars and American

Interests. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008. Pp.204.

$25.00, PB. ISBN 0-801-88989-8.

Steven David has written an important and serious book on how

internal wars can harm American strategic interests. Focusing on

China, Mexico, Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia as the most dangerous

possible sites of civil war (p.153), David argues that state collapse and

internal rebellions can generate unintended but devastating spillover

effects that include loose nuclear weapons, massive refugee flows, and

global economic shocks. Catastrophic Consequences is valuable both

for its cogent, straightforward analysis and for bringing together a set

of important cases that are rarely compared to one another. The book

builds on Davids excellent previous research on the links between

internal and external security.

David argues that the United States is highly vulnerable to the effects

of foreign civil wars. He analyzes China, Mexico, Pakistan, and Saudi

Arabia in terms of the potential danger their collapse or disarray would

pose to the United States, the likelihood and causes of possible civil war

within each state, and the possible results of this instability. Escalating

unrest in Pakistan carries with it the most alarming risks, with the

possibility that a fractured or overwhelmed Pakistan Army loses

control of nuclear assets to Islamist radicals who could then attack the

US. He rightly notes that full-scale state collapse in Pakistan would

pose a uniquely horrific threat to American interests because it brings

together a witches brew of capability and instability (p.50).

In Saudi Arabia, rebellion against and conflict within the royal family

could lead to the destruction of crucial oil infrastructure that would

badly damage the American, and global, economy. David correctly

identifies the current obstacles to rapid US adaptation to a massive and

prolonged oil shock.

The dangers presented by violence and instability in Mexico are

found in flows of refugees to the US, shocks to the American economy,

and the safety of Americans in Mexico. This focus on Mexico is

Downloaded by [King's College London] at 08:17 04 November 2013

788 Book Reviews

particularly prescient as that country descends further into drug-fueled

violence.

Finally, waves of unrest, rebellion, and economic collapse within

China could have devastating effects on the global economy and

security in Asia. He describes a China very much at odds with

optimistic predictions about its future, one in which a fragile banking

system, corrupt institutions, and various demographic imbalances

create severe risks to the countrys stability.

While David overstates the case that civil wars have been largely

ignored by scholars and policymakers (p.2), since a huge amount of

attention has been paid to failed states, ungoverned spaces, and

American interventions from Haiti to Kosovo, he is absolutely right to

highlight the importance of internal conflicts. Davids arguments are

lucid and provocative, and they need to be carefully considered by

scholars, analysts, and policymakers.

Yet Catastrophic Consequences leaves open several questions and

concerns. First, Davids approach lumps together a wide variety of

types of internal conflicts under a shared banner, from martial law

to political party polarization to state collapse to peripheral

insurgency. These forms of rebellion and contentious politics have

very distinct origins and consequences, but David tends to identify

them one after another without much differentiation, leading to a set

of laundry lists of disaster. There is much more room to parse out

how variation in the type and intensity of internal conflict in each

case would affect American interests. In China, there is a huge

difference between chaotic state collapse and increasing nationalist

militarization over the issue of Taiwan. Regional insurgencies against

the Pakistani state are far less serious than a direct fracturing of

the states coercive apparatus. The level of unrest in Saudi Arabia

could range from a minor blip to a massive supply crisis, and it

matters enormously which is most likely and under what circumstances.

Some of the possible scenarios David presents are not just different

but also diametrically opposed to another. For instance, the Chinese

state may split and collapse into factional feuding (p.143), or its

increasingly professionalized, capable, and organized military may

overthrow its civilian masters (p.142). It is hard to reconcile the statecollapse future with the praetorian-state future: they cannot be equally

likely or driven by the same causes.

Mexico is presented as a state with a political and security elite that is

thoroughly enervated and infiltrated by drug money and corruption

(pp.10610), yet David also argues that it is easy to foresee the

emergence of a Mexican leader who will not tolerate this growing state

within a state and undertake a serious effort to rid Mexico once and for

Downloaded by [King's College London] at 08:17 04 November 2013

Book Reviews 789

all of the drug cartels (p.114). Given the detailed analysis underlying

the former claim, the latter assertion comes as a surprise.

Second, David spreads himself too thin in the empirical research,

trying to offer compelling and comprehensive treatments of four

incredibly complex countries. The author is to be commended for his

ambition and effort, but the errors and omissions in the case of Pakistan

illustrate some of the problems that come with this approach. He

makes some minor mistakes (the plural of madrassah should be

madaris for instance), but others are much more significant.

David never discusses the Muhajir insurgency and related ethnic

conflict in Karachi, Pakistans volatile economic hub and largest city,

which has contributed to endemic national instability. In addition, his

claim that the 2002 election results in the North West Frontier Province

(NWFP) showed that the Islamist and separatist movements became

one and the same (p.72) ignores the deep-seated rivalry between

Islamist parties and the Pashtun nationalist Awami National Party

(ANP), which won the NWFP in 2008. This leads to a serious

misreading of Pashtun separatism and its possible implications for the

Pakistani state. Regionalist sentiment in Sindh, Karachi, Baluchistan,

and the NWFP has in fact traditionally been opposed to radical Islamist

politics. For this reason among others, Davids argument that the

Baluch revolt is only less slightly dangerous (p. 68) than the Al-Qaeda

and Taliban presence in the NWFP is not very credible.

Davids concerns about the Pakistani nuclear arsenal are understandable and articulately framed, but he offers very little detail

about the command structure, organizational functioning, and

history of the Pakistani nuclear establishment, which is absolutely

essential to any balanced assessment of the risks of nuclear loss.

There are only a few brief paragraphs on this essential topic (pp.58

63). Similarly, there is no in-depth analysis of the political interests

of the pivotal military, which is portrayed both as the one

institution that holds the country together (p.64) and as extraordinarily inept (p.66). Most curiously, David writes that the major

question regarding Pakistan is not whether civil war will break out,

but why it has not done so already (p.76). As of the books

publication in 2008, an intense insurgency had been raging in the

NWFP and parts of Baluchistan for several years accompanied by

mass-casualty bombings and heavy military losses. Civil war had

already come to Pakistan.

Third, the approach of Catastrophic Consequences is forwardlooking and by its very nature speculative. This is useful for policy and

planning purposes, but the cost is a lack of structured historical analysis

on how civil wars have (and have not) influenced American interests in

the past. This would have both provided a valuable, lasting scholarly

Downloaded by [King's College London] at 08:17 04 November 2013

790 Book Reviews

contribution and more clearly explained Davids expectations for

future contingencies in China, Mexico, Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia.

There are also dangers to this speculative approach because core

assumptions can become rapidly obsolete. While Davids arguments

look to be increasingly supported in Mexico, the end of military rule

and resurgence of counterinsurgency efforts in Pakistan undermine

some of the arguments he presents. Similarly, the reduction of

militant violence in Saudi Arabia from its peak around 2004 may

downgrade our fears of large-scale political unrest in the country.

The shelf life of Catastrophic Consequences thus may be limited by

this approach.

Despite these concerns, Davids book is well worth reading and

pondering. It synthesizes a huge amount of information into a

compelling argument. Crucially, Catastrophic Consequences also

suggests a set of interesting research questions through which to

further explore the hugely important relationships between wars within

states and conflicts among them.

PAUL STANILAND 2010

University of Chicago

Joshua Cooper Ramo, The Age of the Unthinkable: Why the New

World Disorder Constantly Surprises Us and What We Can Do About

It. New York: Little, Brown, 2009. Pp.280. $25.99, HB. ISBN 978-0316-11808-8.

Drawing an analogy from the early twentieth-century Einsteinian

revolution in physics, Ramos thesis is that a similar revolution in

politics, particularly foreign policy, is now required in order for us (for

which, read US) to thrive and survive in the modern global

environment of accelerating change and ever deeper complexity. Ramo

argues persuasively that the old laws of (inter)national power are

increasingly redundant in effecting positive change and irrelevant to the

reality of global systems.

This book is unlikely to appeal to political realists, for whom talk of

non-state power or state non-power is often an uncomfortable and

unresolved distraction. Realists, though, should remember that their

worldview is predicated on the notion that without states, there is

anarchy. In a world that increasingly seems anarchic, then perhaps we

should re-evaluate the Westphalian system in terms of success and

failure of the nation-state?

Democratic peace theory may hold true for democracies but it says

little about wars prosecuted by them against non-democratic nations.

Downloaded by [King's College London] at 08:17 04 November 2013

Book Reviews 791

Nor has neo-Wilsonian democracy cured the world of war and want, as

famously suggested by Francis Fukuyama in The End of History and

the Last Man (1992). The US-led war on terror has succeeded only in

creating more terrorists, an empirical proof surely contrary to its stated

objectives. Self-balancing and largely self-regulating global capital

markets have proven to be incapable of balancing or regulating

effectively enough to stave off near-collapse and subsequent economic

misery to millions. Capitalism itself, and its Cold War foe, communism,

have in most cases achieved the very opposite of their aims of bringing

prosperity, health and happiness to all.

Ramos does not suggest that the world is anarchic, however. His

view is that the world is in a state of organised instability, a concept

drawn from the physical sciences, in particular chaos theory and

complexity science. In this system, we never know what event, object or

person may prove to be responsible for triggering unexpected and

occasionally catastrophic change. The scientific metaphor runs through

the book and also provides it with its conceptual basis. This is a

common and effective conceit but has its limitations. There is little need

to refer to the physics of politics, for example, when all one is

referring to is political economy, a term of sufficient currency and

utility to satisfy most authors.

Our current institutions are inherently incapable of grasping the idea

of organised instability and therefore formulate policy via outmoded

thought and practice. Essentially, they make bad policy because they do

not understand the environment in which they operate, and are too

lethargic and inflexible to adapt and respond. The old rulebooks of

cause and effect, deterrence and defence, are no longer applicable,

relying as they do on monolithic organising principles. Ramo is

encouraging policy-makers to take a good hard look at the world

around them and at themselves and then begin reconfiguring power

structures and decision-making processes in order to generate good and

appropriate policy that reflects the dynamism of a complex world.

Through a series of diverse case studies Ramo draws conclusions

about how some people and organisations are thriving in an unstable

world. At the heart of them all is a reliance on quick-wittedness,

innovation, pragmatism, and an eye for opportunity. This holds true as

much for Hizballah as it does for Silicon Valley entrepreneurs. The bulk

of the book is taken up with describing how people are adapting

successfully across the world while traditional structures are falling

behind. Ramo writes in engaging fashion, is adept at linking across

times and subjects, and the reader is left in little doubt that he is

definitely on to something.

However, as a guide to how we can save ourselves (p.8) the

book inevitably falls short. Although Ramo does not claim to be

Downloaded by [King's College London] at 08:17 04 November 2013

792 Book Reviews

prescriptive in his recommendations for how this can be achieved, he

does not offer anything likely to be of interest to those who should

perhaps be reading this book in the first place: policy-makers.

Although the author writes encouragingly of returning a sense of

agency and responsibility to weary citizens everywhere, if our

institutions really do need to change then how best should that be

achieved? Ramo offers no solutions in this department, other than a

refocusing from security to resilience, learning from Oriental

concepts of indirection rather than confrontation, and an appreciation of context. His suggestion that we view threats as systems,

rather than objects, is wise but already part of military planning, if

not political decision-making.

More revealing though is the discovery of sufficient typographic

errors and egregious mistakes the Rwandan genocide was in 1994,

not 1995 (p.82) coupled with frequent references to the still unfolding

economic crisis, to suggest that this volume may perhaps have been

rushed to publication. It feels unfinished and drops away alarmingly

towards the end without satisfactory conclusion. Ramo could quite

easily defend this on the basis that in his worldview nothing is ever

finished and, certainly, if his ideas are to be taken seriously then this is

all a work-in-progress anyway. He also leaves us in no doubt as to his

high-flying social environment, reflecting perhaps his hobby of

competitive aerobatics.

The book is accompanied by an eclectic bibliography, the constituents of which are, in the habit of popular volumes, annoyingly

unreferenced in the text. Although a useful reading list, there are

omissions. Given its likely readership one could reasonably expect to

find listed John Robbs Brave New War (2007), Nassim Nicholas

Talebs The Black Swan (2007), and General Sir Rupert Smiths The

Utility of Force (2005). Relying as it does in part on chaos theory, the

omission of James Gleicks groundbreaking access-level book, Chaos:

Making a New Science (1987), is curious.

Despite its limitations The Age of the Unthinkable deserves wide

readership which, judging by its media reception in the US, it is likely to

gain. Joshua Cooper Ramo is erudite and imaginative, a combination

that means that although he may not have all the answers he is entirely

competent to successfully communicate complexity with clarity. This is

no mean feat, and the book offers sufficient insight into the modern

world, its characteristics and its problems, that it commends itself to

the academy and to the wider public and, of course, to policy-makers

everywhere.

TIM STEVENS 2010

Kings College London

Book Reviews 793

Downloaded by [King's College London] at 08:17 04 November 2013

Audrey Kurth Cronin, How Terrorism Ends: Understanding the

Decline and Demise of Terrorist Campaigns. Princeton, NJ: Princeton

University Press, 2009. Pp.330. $29.95, HB. ISBN 978-0-691-13948-7.

Audrey Kurth Cronin observes that despite variation in casualties,

objectives, and longevity, all previous terrorism campaigns have had

one key characteristic in common: they ended. Therefore, she argues

that the best way to develop counterterrorism policy is to thoroughly

analyze the final stages of previous terrorist organizations in the hope

that the resulting findings can provide improved guidance to those who

wish to better understand terrorism campaigns and bring them to a

close.

To accomplish this, Cronin analyzed 457 campaigns from the

Memorial Institute for the Prevention of Terrorism (MIPT) Terrorism

Knowledge Base in addition to numerous short case studies, which

helped to illustrate the causal pathways of the demise of previous

campaigns. The six pathways Cronin identified serve as the foundation

for the book and are described as follows: (1) capture or killing the

groups leader (2) entry of the group into a legitimate political process

(3) achievement of the groups aims (4) implosion or loss of the groups

public support (5) defeat and elimination by brute force (6) transition

from terrorism into other forms of violence. (p.8)

Cronin presented these mechanisms as part of an analytical framework for academics and policymakers to better understand the

dynamics of terrorism and then used the framework herself to

evaluate the probable course of Al-Qaedas ultimate demise. She

claims that Al-Qaeda is unlikely to end due to decapitation of its

leadership (too late), achievement of its goals (impossible), or

elimination by brute force (counterproductive and improbable).

Instead, she argues that Al-Qaeda is likely to meet its demise due to

the loss of public support from targeting missteps or a transition to

other methods of violence like insurgency, nudged along by states

offers of negotiations and/or amnesty to Al-Qaedas peripheral

elements.

As Cronin points out, far more scholarship has been completed on

the causes of terrorism, but the end of a campaign cannot be

understood simply as the absence of its original causes. Her analysis

of dynamics that emerge after a campaigns initiation, therefore,

represents the first of two major contributions to the counterterrorism

literature. The second results from the structure of her analysis. Much

of the existing counterterrorism literature seeks to improve state policy,

and so it focuses on what states have done right and wrong in the past

and makes recommendations about what they can do better in the

future. This research design is not without merit, but its resulting policy

Downloaded by [King's College London] at 08:17 04 November 2013

794 Book Reviews

recommendations can pose a problem when they are based on a statecentric concept of counterterrorism.

As Cronin effectively argues, many of the reasons why terrorism ends

from infighting to a loss of popular support have little to do with the

actions of states. Therefore, effective counterterrorism policy has as

much to do with the realization by state actors of how often they play

an inconsequential or even counterproductive role in the demise of

terrorist organizations as it does with attempts to actively thwart their

activities. Cronins broader analysis of all possible pathways to

terrorisms end reveals that studying the objective of most counterterrorism policies (the end of terrorism) may be more useful than

simply studying the items of interest (the policies themselves), and may

well represent the best way to get the latter right.

Unfortunately, a few key methodological choices Cronin makes, once

her focus on the demise of terrorist campaigns is set, weakens some of

her empirical claims. First, her study selects both independent and

dependent variables to a considerable degree. It is one thing to want to

understand the manner in which terrorist campaigns end; it is another

to draw conclusions almost exclusively by analyzing the presence of

those pathways and the termination of campaigns. Doing so may limit

the identification of key independent variables and related hypotheses,

make assessment of their relative explanatory power and scope

conditions problematic, and generally draw into question associated

causal claims. In the absence of a more thorough examination of

instances lacking her independent variables, or instances of endurance

alongside her studies of campaign demise, her findings are less robust

than they otherwise might be.

This leads to the second problem with Cronins methodology,

namely, the set-up of her case studies. The author repeatedly labels her

cases comparative, but it is often unclear exactly what she is

comparing or how the comparison is being structured to yield powerful

results. Most of her cases resemble brief attempts (often three pages or

less and at times even less than one page) at describing one of her six

causal pathways with some historical context. The vast majority are

thus largely illustrative and lack consideration of competing explanations for the end of campaigns or any attempt to hold key lurking

variables constant across cases.

That said, Cronin does offer a few promising exceptions, particularly

in the section on decapitation. Her analysis of The Shining Path, The

Kurdistan Workers Party, and the Real Irish Republican Army (RIRA)

included time series data on group attacks overlaid with the date of

capture of key leaders, which allows the reader to better assess this

explanatory variable in greater context. As Cronin notes, the data is

imperfect and challenges to assembling it in this manner abound, but

Downloaded by [King's College London] at 08:17 04 November 2013

Book Reviews 795

these examples do provide a positive step in analyzing her claims

against the full life span of the groups, if not in comparison with

competing explanations. Ultimately, the number of cases Cronin

considers is impressive, and since her primary purpose is the

presentation and specification of mechanisms rather than the testing

of causal claims, these methodological critiques are not fatal to the

larger project, and they present opportunities for future research.

Cronin succeeds in the central goal of her study, which is to present a

template for understanding the demise of terrorist campaigns that

future scholars can learn from, debate, and revise. Unfortunately,

Cronins project fails to fully incorporate two recent similar studies, the

article Why Terrorism Does Not Work by Max Abrahms (International Security, 2006) and Why Terrorist Groups End: Lessons for

Countering Al-Qaeda (2008) by Seth Jones and Martin Libicki, thereby

missing an opportunity to launch that debate and further advance the

subfield.

Cronin could have examined best practices for analyzing terrorisms

end using large statistical samples, which has not been attempted by

many scholars. In particular, she could have analyzed methodological

difficulties shared by all three studies in isolating the effects of the use of

terrorism by a single group on achievement of a political objective.

Although Cronins awareness of this issue is clear from her discussion

of two case studies of group success the Irgun Zvai Leumi and the

African National Congress she does not suggest or utilize any

qualitative or quantitative methodology for better isolating terrorisms

impact. This presents a further avenue for future research.

The fact that Cronins book raises more questions than it answers

may ultimately be a positive, because she aims to provide a wideranging analysis of a subject in its early phases that can serve as a

springboard to future studies. How Terrorism Ends is, therefore, a

worthwhile book for both academics and policymakers. If a reader

agrees with some points and finds others lacking, but ultimately

considers how to grapple with terrorism from a new perspective,

Cronin will have succeeded in her aims.

PETER J. P. KRAUSE 2010

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

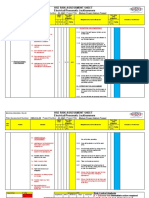

- Physics Assessment TaskDocumento10 paginePhysics Assessment TaskAnonymous QvdxO5XTRNessuna valutazione finora

- TransferDocumento14 pagineTransferAnonymous QvdxO5XTRNessuna valutazione finora

- HSC Physics Paper 2 Target PDFDocumento17 pagineHSC Physics Paper 2 Target PDFAnonymous QvdxO5XTR63% (8)

- Series Paralell 2 Lesson PlanDocumento2 pagineSeries Paralell 2 Lesson PlanAnonymous QvdxO5XTRNessuna valutazione finora

- TransferDocumento14 pagineTransferAnonymous QvdxO5XTRNessuna valutazione finora

- "A" Level Physics Gravitational Fields and Potential: TO DO Qs 9.1 and 9.2 Hutchings P 121Documento9 pagine"A" Level Physics Gravitational Fields and Potential: TO DO Qs 9.1 and 9.2 Hutchings P 121Anonymous QvdxO5XTRNessuna valutazione finora

- Ferrill Digital Curriculum Pendulum Lab RevisedDocumento5 pagineFerrill Digital Curriculum Pendulum Lab RevisedAnonymous QvdxO5XTRNessuna valutazione finora

- ElectricfldDocumento3 pagineElectricfldAnonymous QvdxO5XTRNessuna valutazione finora

- EmaginDocumento10 pagineEmaginAnonymous QvdxO5XTRNessuna valutazione finora

- SolidsDocumento6 pagineSolidsAnonymous QvdxO5XTRNessuna valutazione finora

- Rotational DynamicsDocumento8 pagineRotational DynamicsAnonymous QvdxO5XTRNessuna valutazione finora

- "A" Level Physics: Systems and Processes Unit 4Documento3 pagine"A" Level Physics: Systems and Processes Unit 4Anonymous QvdxO5XTRNessuna valutazione finora

- Tap 129-6: Capacitors With The Exponential EquationDocumento3 pagineTap 129-6: Capacitors With The Exponential EquationAnonymous QvdxO5XTRNessuna valutazione finora

- Resistors I ParallelDocumento3 pagineResistors I ParallelAnonymous QvdxO5XTRNessuna valutazione finora

- Reference Manual: Digital CameraDocumento96 pagineReference Manual: Digital CameraAnonymous QvdxO5XTRNessuna valutazione finora

- LAB: Acceleration Due To Gravity: NameDocumento3 pagineLAB: Acceleration Due To Gravity: NameAnonymous QvdxO5XTRNessuna valutazione finora

- Potential and Kinetice Energy WorksheetDocumento2 paginePotential and Kinetice Energy WorksheetAnonymous QvdxO5XTRNessuna valutazione finora

- TAP 129-5: Discharging A CapacitorDocumento5 pagineTAP 129-5: Discharging A CapacitorAnonymous QvdxO5XTRNessuna valutazione finora

- "A" Level Physics Gravitational Fields and Potential: TO DO Qs 9.1 and 9.2 Hutchings P 121Documento9 pagine"A" Level Physics Gravitational Fields and Potential: TO DO Qs 9.1 and 9.2 Hutchings P 121Anonymous QvdxO5XTRNessuna valutazione finora

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocumento15 pagine6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- Static Electricity NotesDocumento22 pagineStatic Electricity NotesAnonymous QvdxO5XTR0% (2)

- PrefaceDocumento16 paginePrefaceDhias Pratama LazuarfyNessuna valutazione finora

- Electric Quantities NoteDocumento10 pagineElectric Quantities NoteAnonymous QvdxO5XTRNessuna valutazione finora

- Electrical Power WSDocumento5 pagineElectrical Power WSAnonymous QvdxO5XTRNessuna valutazione finora

- Episode 218: Mechanical Power: × VelocityDocumento10 pagineEpisode 218: Mechanical Power: × VelocityAnonymous QvdxO5XTRNessuna valutazione finora

- Electric Field NotesDocumento3 pagineElectric Field NotesAnonymous QvdxO5XTRNessuna valutazione finora

- Physics DataDocumento7 paginePhysics DataAnonymous QvdxO5XTRNessuna valutazione finora

- Here: Electricity and Magnetism School of Physics PDFDocumento6 pagineHere: Electricity and Magnetism School of Physics PDFAnonymous QvdxO5XTRNessuna valutazione finora

- Electric Quantities NoteDocumento10 pagineElectric Quantities NoteAnonymous QvdxO5XTRNessuna valutazione finora

- Moong Dal RecipeDocumento6 pagineMoong Dal RecipeAnonymous QvdxO5XTRNessuna valutazione finora

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- SMTP/POP3/IMAP Email Engine Library For C/C++ Programmer's ManualDocumento40 pagineSMTP/POP3/IMAP Email Engine Library For C/C++ Programmer's Manualadem ademNessuna valutazione finora

- Part - 1 LAW - 27088005 PDFDocumento3 paginePart - 1 LAW - 27088005 PDFMaharajan GomuNessuna valutazione finora

- Phase/State Transitions of Confectionery Sweeteners: Thermodynamic and Kinetic AspectsDocumento16 paginePhase/State Transitions of Confectionery Sweeteners: Thermodynamic and Kinetic AspectsAlicia MartinezNessuna valutazione finora

- July 2006 Bar Exam Louisiana Code of Civil ProcedureDocumento11 pagineJuly 2006 Bar Exam Louisiana Code of Civil ProcedureDinkle KingNessuna valutazione finora

- The Wisdom BookDocumento509 pagineThe Wisdom BookRalos Latrommi100% (12)

- Robber Bridegroom Script 1 PDFDocumento110 pagineRobber Bridegroom Script 1 PDFRicardo GarciaNessuna valutazione finora

- Vulnerabilidades: Security Intelligence CenterDocumento2 pagineVulnerabilidades: Security Intelligence Centergusanito007Nessuna valutazione finora

- 9 Electrical Jack HammerDocumento3 pagine9 Electrical Jack HammersizweNessuna valutazione finora

- FS 1 - Episode 1Documento18 pagineFS 1 - Episode 1Bhabierhose Saliwan LhacroNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Study - Lucky Cement and OthersDocumento16 pagineCase Study - Lucky Cement and OthersKabeer QureshiNessuna valutazione finora

- Securingrights Executive SummaryDocumento16 pagineSecuringrights Executive Summaryvictor galeanoNessuna valutazione finora

- XT 125Documento54 pagineXT 125ToniNessuna valutazione finora

- What Is Degrowth - Demaria Schneider Sekulova Martinez Alier Env ValuesDocumento27 pagineWhat Is Degrowth - Demaria Schneider Sekulova Martinez Alier Env ValuesNayara SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- Puzzles 1Documento214 paginePuzzles 1Prince VegetaNessuna valutazione finora

- Journal of Exceptional Experiences and PDocumento62 pagineJournal of Exceptional Experiences and Pbinzegger100% (1)

- Plessy V Ferguson DBQDocumento4 paginePlessy V Ferguson DBQapi-300429241Nessuna valutazione finora

- Timothy L. Mccandless, Esq. (SBN 147715) : Pre-Trial Documents - Jury InstructionsDocumento3 pagineTimothy L. Mccandless, Esq. (SBN 147715) : Pre-Trial Documents - Jury Instructionstmccand100% (1)

- MPLS Fundamentals - Forwardi..Documento4 pagineMPLS Fundamentals - Forwardi..Rafael Ricardo Rubiano PavíaNessuna valutazione finora

- Solar SystemDocumento3 pagineSolar SystemKim CatherineNessuna valutazione finora

- Body ImageDocumento7 pagineBody ImageCristie MtzNessuna valutazione finora

- TLE ICT CY9 w4 PDFDocumento5 pagineTLE ICT CY9 w4 PDFMichelle DaurogNessuna valutazione finora

- Keong Mas ENGDocumento2 pagineKeong Mas ENGRose Mutiara YanuarNessuna valutazione finora

- Labor Law Highlights, 1915-2015: Labor Review Has Been in Publication. All The LegislationDocumento13 pagineLabor Law Highlights, 1915-2015: Labor Review Has Been in Publication. All The LegislationIgu jumaNessuna valutazione finora

- MYPNA SE G11 U1 WebDocumento136 pagineMYPNA SE G11 U1 WebKokiesuga12 TaeNessuna valutazione finora

- RBConcept Universal Instruction ManualDocumento19 pagineRBConcept Universal Instruction Manualyan henrique primaoNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 2 Lab Manual ChemistryDocumento9 pagineUnit 2 Lab Manual ChemistryAldayne ParkesNessuna valutazione finora

- Practice Ch5Documento10 paginePractice Ch5Ali_Asad_1932Nessuna valutazione finora

- A1 - The Canterville Ghost WorksheetsDocumento8 pagineA1 - The Canterville Ghost WorksheetsТатьяна ЩукинаNessuna valutazione finora

- The Old Rugged Cross - George Bennard: RefrainDocumento5 pagineThe Old Rugged Cross - George Bennard: RefrainwilsonNessuna valutazione finora

- Hop Movie WorksheetDocumento3 pagineHop Movie WorksheetMARIA RIERA PRATSNessuna valutazione finora