Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Diabetes Self Management

Caricato da

Rizky BangkitTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Diabetes Self Management

Caricato da

Rizky BangkitCopyright:

Formati disponibili

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.

uk/wrap

This paper is made available online in accordance with

publisher policies. Please scroll down to view the document

itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item and our

policy information available from the repository home page for

further information.

To see the final version of this paper please visit the publishers website.

Access to the published version may require a subscription.

Author(s): Jackie Sturt , Hilary Hearnshaw and Melanie Wakelin

Article Title: Validity and reliability of the DMSES UK: a measure of

self-efficacy for type 2 diabetes self-management

Year of publication: 2009

Link to published article: http://dx.doi.org/

10.1017/S1463423610000101

Publisher statement: Cambridge University Press 2009. Sturt, J. et

al. 2009. Validity and reliability of the DMSES UK: a measure of selfefficacy for type 2 diabetes self-management. Primary Health Care

Research & Development, June 2010

Primary Health Care Research & Development page 1 of 8

doi:10.1017/S1463423610000101

RESEARCH

Validity and reliability of the DMSES UK: a

measure of self-efficacy for type 2 diabetes

self-management

Jackie Sturt1, Hilary Hearnshaw1 and Melanie Wakelin2

1

Health Sciences Research Institute, Warwick Medical School, University of Warwick, Coventry CV4 7AL, UK

Statistical Consultant, Wakelin Statistical Services, 42 Tailors, Bishops Stortford, Hertfordshire, UK

Objectives: Self-efficacy is an important outcome measure of self-management

interventions. We aimed to establish UK validity and reliability of the diabetes management self-efficacy scale (DMSES). Methods: The 20 item DMSES was available for

Dutch and US populations. Consultation with people with type 2 diabetes and health

professionals established UK content and face validity resulting in item reduction to

15. Participants were adults with type 2 diabetes enrolled in a randomised controlled

trial (RCT) of the diabetes manual, a self-management education intervention, with an

HbA1c over 7% and who understood English. Baseline trial data and follow-up control

group data were used. Results: A total of 175 participants completed all 15 items.

Pearsons correlation coefficient of 20.46 (P , 0.0001) between the DMSES UK and the

problem areas in diabetes scale demonstrated criterion validity. Intra-class correlation

between data from 67 of these participants was 0.77, demonstrating test-retest reliability. The correlation coefficients between item scores and total scores were .0.30.

Cronbachs alpha was 0.89 over all items. Conclusion: This evaluation demonstrates

that the scale has good internal reliability, internal consistency, construct validity,

criterion validity, and test-retest reliability. Practice Implications: The 15 item

DMSES UK is suitable for use in research and clinical settings to measure the selfefficacy of people living with type 2 diabetes in managing their diabetes.

Key words: diabetes; outcome measure; self-efficacy; self-management

Received 11 November 2009; accepted 10 March 2010

Introduction

International and UK health policy have developed standards stating that people with diabetes

should be empowered and supported to participate in decision-making and self-management to

optimise the control of blood glucose, blood

pressure, and other risk factors for developing the

complications of diabetes (Department of Health,

2002; 2005; International Diabetes Federation,

2003). This marks a shift in the treatment of those

Correspondence to: Jackie Sturt, Health Sciences Research

Institute, Warwick Medical School, University of Warwick,

Coventry CV4 7AL, UK. Email: jackie.sturt@warwick.ac.uk

r Cambridge University Press 2010

with chronic diseases away from health-care

professional management towards ensuring that

patients are enabled to self-manage their health

effectively and engage in active partnership with

health professionals. One of the dominant concepts in the literature on supporting self-management is that of self-efficacy (Day et al., 1997;

Norris et al., 2001; Guevara et al., 2003).

Perceived self-efficacy is a reliable predictor of

behaviour initiation (Bandura, 1977; Gillis, 1993).

It demonstrates its value as the cornerstone of

effective chronic disease self-management through

its increasing use as a self-management research

outcome measure (Lorig et al., 1999; Farmer et al.,

2005; Sturt et al., 2006a; 2006b; Davies et al., 2008).

2 Jackie Sturt, Hilary Hearnshaw and Melanie Wakelin

Perceived self-efficacy is defined as an individuals

perceptions or beliefs about their capabilities to

undertake certain activities (Bandura, 1994). It

influences how they think, feel, become motivated

and behave. People with strong perceptions of

their personal efficacy approach difficult tasks as

challenges to be mastered; they set themselves

challenging goals and maintain strong commitment

to them. In the face of failure they increase their

efforts and rapidly recover their self-efficacy after

setbacks. This efficacious outlook produces personal accomplishments, reduces stress, and lowers

vulnerability to depression. In contrast, people who

doubt their capabilities avoid difficult tasks, they

have low aspirations and weak commitment to

their chosen goals. When faced with difficult tasks,

they dwell on their personal deficiencies and on the

obstacles and their efforts weaken in the face of

these challenges. Individuals with low perceptions

of efficacy are vulnerable to stress and depression

(Bandura, 1994). Self-efficacy is often communicated to lay audiences, for example, in research

measures, as degree of confidence although this is

not technically accurate and Bandura does describe

important differences between confidence and selfefficacy in his web site (http://www.des.emory.edu/

mfp/self-efficacy.html).

Self-efficacy is supported in four ways (in order

of influence): personal mastery experiences,

vicarious (or peer) experiences, emotional state,

and verbal encouragement and it offers a framework for enabling health-care professionals to

guide people towards experiences that will

strengthen their self-efficacy (Bandura, 1977).

Measurement of perceived self-efficacy is behaviour-specific and measurement predicts the

likelihood that an individual will engage in a

behaviour, the degree to which they will persist

and overcome obstacles, and their ultimate success in maintaining behaviour in the longer term

(Bandura, 1977; Sentcal et al., 2000; Sniehotta

et al., 2005). However, measurement is complicated by the lack of generalisability of self-efficacy

between types of behaviour, for example, stopping

smoking and increasing physical activity. Attempts

to develop measures across different behaviour

types have limited usefulness (Bandura, 1997;

2006). Scales to measure perceived self-efficacy

must, therefore, be highly specific to the behaviour or activity of interest, such as aspects of selfmanagement in diabetes.

Diabetes is a complex metabolic condition

requiring high levels of self-efficacy to perform

the many facets of self-management required

for blood glucose control, and hence prevention

of complications. Diabetes self-efficacy measurement scales currently available provide good

psychometric validity for the measurement of

psychosocial aspects of living with diabetes, of

self-management for people with type 1 diabetes,

and for type 2 diabetes self-management for

Dutch/US and Australian populations (Bijl et al.,

1999; Anderson et al., 2000; Van Der Ven et al.,

2003; McDowell et al., 2005). The Dutch/US scale

assesses behavioural aspects of type 2 diabetes

self-management and had the potential to offer a

strongly aligned outcome measure for the type 2

diabetes patient education and self-management

intervention studies that we were designing and

which were strongly influenced by self-efficacy

theory. Scale items assess self-efficacy for performing a range of self-management activities

that will influence blood glucose control including

managing healthy eating and monitoring skin

integrity of the feet (Bijl et al., 1999). A scale for

measuring perceived self-efficacy, validated for

use with a UK population, focusing on diabetesspecific self-management activities would offer a

tool for researchers and clinicians to evaluate

progress towards meeting the UK Diabetes

National Service Framework standards.

The aim of this paper is to present the evaluation of aspects of the validity and reliability of

an adapted version of the Dutch/US diabetes

management self-efficacy scale (DMSES) as a

measure of perceived self-efficacy in relation to

the management of diabetes in patients with type

2 diabetes, in the UK population.

Methods

Adaptation of the Dutch/US DMSES

The 20-item Dutch/US DMSES measures the

individuals efficacy expectations for engaging in

20 type 2 diabetes self-management activities, for

example, taking daily exercise, keeping to a healthy

eating plan when away from home (Bijl et al., 1999).

The scale is scored according to a 15 point numerical scale indicating the level of efficacy expectation

the respondent has for each item with higher

scores indicating greater levels of self-efficacy.

Validity and reliability of the DMSES UK scale 3

The Dutch/US evaluation of the DMSES covered

content and construct validity, internal consistency,

and temporal stability. That process, involving a

panel of experts within diabetes and self-efficacy,

resulted in the reduction of an original 42-item

scale to 20 items. The DMSES was translated from

Dutch to US English as part of the scale development work. The construct validity of the scale was

demonstrated through the findings of a positive

relationship in a second, US-based study, testing

the relationship between the self-efficacy scores of

individuals living with diabetes and the self-efficacy

scores of their significant other for supporting and

assisting them in the 20 self-management activities,

for example, How confident are you that you could

support and assist your significant other in choosing

the correct foods (Shortridge-Bagget and van der

Bijl, 2002).

Assessing face validity

Face validation of a DMSES for the UK started

by consulting with the Warwick Diabetes Research

& Education User Group (WDREUG), a lay

advisory group of 1012 people living with diabetes,

during two meetings over six months (Lindenmeyer

et al., 2007). The WDREUG provided advice to

ensure appropriate use of vocabulary (eg, blood

glucose monitoring) and concepts (eg, confidence),

which resulted in changes made to items, for

example, diabetic diet was replaced by healthy

eating pattern. Following WDREUG consultation

and with regard to the literature (Donaldson, 2003)

the stem phrase I am confident that y was used

to precede each item in the 20-item DMSES UK.

The 20 UK items are described in Table 1.

The five-point response scale used in the

Dutch/US DMSES has a poorer predictive capacity than a 0 to 10-point scale (Pajares et al.,

2001). The DMSES UK incorporated an 11-point

010 scale reflecting Banduras thesis (Bandura,

2006). The WDREUG advised on the anchor

point terms used in the scale, which were as follows; 01 Cannot do at all, 4/5 Maybe yes maybe

no, 9/10 Certain can do. The centre anchor point

recommended by Bandura is moderately certain

can do. The WDREUG felt this was ambiguous

and using Maybe yes, maybe no enabled a

responder to judge their certainty based on a

collective experience of their perceived confidence for a particular behaviour, indicating that

Table 1 Initial version of the DMSES UK with 20 items

I am confident that

1 I am able to check my blood/urine sugar if necessary

2 I am able to correct my blood sugar when the sugar

level is too high

3 I am able to correct my blood sugar when the blood

sugar level is too low

4 I am able to choose the correct food

5 I am able to choose different foods and stick to a

healthy eating pattern

6 I am able to keep my weight under control

7 I am able to examine my feet for cuts

8 I am able to take enough exercise, for example,

walking the dog or riding a bicycle

9 I am able to adjust my eating plan when ill

10 I am able to follow a healthy eating pattern most of

the time

11 I am able to take more exercise if the doctor advises

me to

12 When taking more exercise I am able to adjust my

eating plan

13 I am able to follow a healthy eating pattern when I

am away from home

14 I am able to adjust my eating plan when I am away

from home

15 I am able to follow a healthy eating pattern when I

am on holiday

16 I am able to follow a healthy eating pattern when I

am eating out or at a party

17 I am able to adjust my eating plan when I am feeling

stressed or anxious

18 I am able to visit my doctor once a year to monitor

my diabetes

19 I am able to take my medication as prescribed

20 I am able to adjust my medication when I am ill

DMSES 5 diabetes management self-efficacy scale.

some days they might be more confident than

others. The scale instructions were determined with

reference to Banduras guidance on the construction of self-efficacy scales and with regard to the

opinions of the users (Bandura, 1997). The scale

was intended for self-completion, in private, so clear

instructions were an important aspect of the scale.

The Flesch reading ease score (tool available in

Microsoft Office Word) for the DMSES UK was

assessed as 82.9% or grade 2.6 equivalent to a

reading age of seven to eight years, and therefore

appropriate. This process of consultation in adapting the scale established high-face validity.

Assessing content validity

Once face validity was established we amended

the DMSES and content validity was assessed

4 Jackie Sturt, Hilary Hearnshaw and Melanie Wakelin

Table 2 Redundant items from initial 20-item DMSES UK

Item Reason for redundancy

5

14

15

18

Item 5 (concerning choice and adherence) is an

amalgamation of item 4 (concerning choice) and

item 10 (concerning adherence), indicating limited

value

Item 8 wording enough exercise is a subjective

and interpretive question whereas adherence to

doctor advice (item 11) is an appropriate selfmanagement activity for type 2 diabetes. Item 11

therefore retained

Item meaning was closely related to item 13 and

offered no additional challenge in relation to type 2

diabetes. Respondents were unable to distinguish

between healthy eating pattern and eating plan

supporting the removal of item 14

Being on holiday is a subset of being away from

home and respondents were unable to distinguish

between items 13 and 15. Respondents were

unable to distinguish between healthy eating

pattern and eating plan. The removal of item 15

removed the duplication

Access to annual GP care in the UK is a relatively

certain activity and suggests that item 18 does not

lend itself to Likert scale measurement. This item

was removed

DMSES 5 diabetes management self-efficacy scale.

with both people living with type 2 diabetes

and with diabetes health-care professionals. Thirty

individuals attending two lay diabetes events in

2003, volunteered to complete the 20-item DMSES

UK with the available support of a researcher (JS/

HH). During completion the volunteers with type 2

diabetes identified duplications and ambiguities in

the scale, which were recorded in field notes. This

process confirmed the views of the WDREUG.

Health professionals undergoing continuing

professional development in diabetes care at the

Warwick Medical School were also consulted on

the validity of the constructs. Group discussions

were held with three cohorts of professionals,

approximately 20 people per cohort. This revealed

ambiguity around a number of items and some

duplication. The professional and lay consultation

led to the removal of five items from the DMSES

UK. Two items were ambiguous (items 8,18) and

three involved duplicate items or elements of

items (items 5,14,15) (Table 2). The health professionals confirmed that the scale content was

sufficiently broad to cover the salient and challenging aspects of self-managing type 2 diabetes

giving high content validity. The face and content

validity of the DMSES UK was determined to be

of sufficient strength for the revised 15 item scale

to undergo further psychometric evaluation.

Diabetes manual randomised controlled trial

(RCT) and participants

Evaluation of the criterion and construct validity

and the reliability of the DMSES UK was undertaken using data from the cluster randomised trial of

the Diabetes Manual, a structured education programme for type 2 diabetes undertaken from 2005

to 2007 (Sturt et al., 2006a; 2006b; 2008). RCT participants were 245 people with type 2 diabetes resident across the West Midlands, UK. All participants

were recruited from primary care and randomised

to receive the diabetes manual intervention or a sixmonth deferred intervention. The diabetes manual is

a self-management and structured education programme to be used by practice nurses and patients

on a one to one basis. It consists of two-day facilitator training for the nurse, a patient workbook

for recommended completion over three months, a

frequently asked questions CD, a relaxation CD, and

three nurse-delivered telephone support calls. The

aim of the intervention is to strengthen the patients

self-efficacy by developing skills and confidence in

managing their diabetes, quickly, and progressively.

The intervention is theoretically underpinned by

self-efficacy theory (Bandura, 1977).

RCT outcome measures

Baseline data were collected from 245 participants before randomisation and consisted of

HbA1c as the primary outcome and completion

of a six-page questionnaire including the 15 item

DMSES UK, the 20 item problem areas in diabetes (PAID) scale (Polonsky et al., 1995), and

10 demographic questions. The PAID scale is a

20-item measure of diabetes-specific emotional

distress; with a maximum score of 100 and higher

scores indicting greater emotional distress. The

maximum score on the DMSES UK is 150 with

higher scores indicating higher self-efficacy. Since

higher self-efficacy is related to lower emotional

distress (Fisher et al., 2007) a strong correlation

between low PAID scores (a gold standard),

indicating low distress, and high scores on the

DMSES UK, indicating high self-efficacy, would

indicate criterion validity. Two hundred and

Validity and reliability of the DMSES UK scale 5

thirty-two (95%) randomised participants completed some elements of the questionnaire, of

whom 175 (71%) participants responded to all of

the DMSES UK questions. These 175 participants

form the sample used for this psychometric evaluation of the DMSES UK.

At the six-month follow-up for the trial, the sixpage questionnaire was completed again by participants. Within four weeks of that, all control

group patients were sent a repeat questionnaire.

This group was chosen for the test-retest because

they were awaiting the deferred intervention and

could be expected to complete the repeat questionnaire. The repeat questionnaire was returned

by 67 participants.

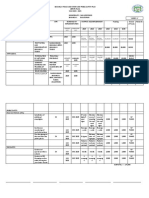

Table 3 Characteristics of participants

Demographic and clinical characteristics of participants

No. of participants

Age median (quartiles)

Gender no (%)

Men

Women

No. of years since diagnosed with

diabetes, no. (%)

,1 year

115 years

.15 years

Median HbA1c % (quartiles)

Mean DMSES score (SD)

Mean PAID score (SD)

175

61 (52, 70)

110 (63%)

65 (37%)

12

155

8

8.5

103

21

(7%)

(89%)

(4%)

(7.6, 9.7)

(27.8)

(15.4)

DMSES 5 diabetes management self-efficacy scale;

PAID 5 problem areas in diabetes.

Results

Patient characteristics

The demographic and clinical characteristics of

the participants who completed the DMSES UK

questions at baseline are summarised in Table 3.

Principal component analysis

Principal components analysis was used to

investigate whether DMSES should be considered as several subscales or as one general

factor. The item coefficients for the first principal

component varied from 0.38 to 0.80 demonstrating that it was indeed a weighted average of all

questions, rather than being dominated by a small

subset of questions. The first principal component

accounted for 41% of the total variance. The

second component accounted for only 11% of the

variance and the third component accounted for

10%. The scree plot (Figure 1) indicates that one

factor was important, confirmed as a weighted

average, supporting the reporting of DMSES as

one overall score.

Internal reliability and internal consistency

The correlation coefficients between item scores

and total scores were all .0.30 (minimum 5

0.34, maximum 5 0.71). Internal consistency was

demonstrated by a Cronbachs alpha of 0.89 over

all 15 items. Internal reliability of DMSES UK was

therefore deemed to be acceptable.

Scree plot for baseline DMSES UK (n=175)

7

6

Eigenvalue

5

4

3

2

1

0

0

Figure 1

6

5

7

8

9 10

Principal Component No.

11

12

13

14

15

Scree plot for baseline diabetes management self-efficacy scale (DMSES UK; n 5 175)

6 Jackie Sturt, Hilary Hearnshaw and Melanie Wakelin

Criterion validity

A Pearsons correlation coefficient of 20.46,

P , 0.0001 was found indicating a negative correlation between DMSES scores and PAID scores.

This demonstrates the criterion validity of the

DMSES, since the PAID is a well established and

validated gold standard scale (Fisher et al., 2007).

Construct validity

A negative correlation between DMSES scores

and HbA1c (Pearsons correlation coefficient

20.21, P 5 0.002) was found. Since higher selfefficacy should lead to greater self-care behaviours resulting in lower blood glucose levels and

ultimately lower HbA1c levels (Fisher et al.,

2007), this demonstrates the construct validity of

the DMSES.

Test-retest reliability

Analysis of test-retest data from 67 participants, who completed the DMSES UK questionnaire twice within a four-week time period,

produced an intra-class correlation of 0.77. This

demonstrates the reliability over time of the

DMSES UK.

Discussion

The results from this evaluation of aspects of the

validity and reliability of DMSES UK, demonstrate that the scale has good internal reliability

and high internal consistency. DMSES UK score

was found to be negatively correlated with both

PAID score and HbA1c. These findings demonstrate the criterion validity and the construct

validity of DMSES UK. Acceptable test-retest

reliability was demonstrated by an intra-class

correlation coefficient of 0.77.

The data were drawn from an intervention

study in which participants consented to a programme of self-management education with some

burden attached. This may represent a different

population from one who were just asked to

complete a single questionnaire on two occasions.

The trial participants were not found to differ

from the eligible participants on any variable

although the low 18.5% RCT response rate indicates that acceptance of burden may have been a

distinguishing feature of our participants (Sturt

et al., 2008). Our participants also had a mean

diabetes distress level of 21 as measured by the

PAID scale at baseline. This compares slightly

lower to typical diabetes out-patient populations

in the USA and Germany where scores in the

range of 2030 were detected (Polonsky et al.,

1995; Welch et al., 2003). These study sample

factors may distort the validity of the findings

were it used on a population not involved in an

intervention trial. One further limitation may be

the anchor points of maybe yes, maybe no which

may confound moderate efficacy with uncertainty.

Given the observed inter-items and inter-scale

correlations, we expect any such confounding to

have been small.

A validation and psychometric evaluation of the

20 item DMSES in an Australian population also

reported some probable redundancy (McDowell et

al., 2005). The authors identified inter-item correlations between items 2/3, 8/11, 13/14, 13/15, and

14/15, which map well onto the items found to be

redundant in the DMSES UK. The DMSES UK

is the first national validation and psychometric

evaluation of the DMSES to have been used as

an outcome measure in RCTs of self-management

interventions (Sturt et al., 2008; Dale et al., 2009).

The DMSES UK has undergone face validation for

use in audio-delivery and symbol self-completion

for Bangladeshi and Pakistani populations resident

within the UK whose main language has no written

form (Lloyd et al., 2008). The psychometric evaluation of the DMSES UK now enables confident

use of the Sylheti and Mirpuri DMSES UK scales

in diabetes self-management intervention studies

for these South Asian populations vulnerable to

diabetes and its consequences.

Conclusions

The DMSES UK is available as a measure of

diabetes management self-efficacy for both clinical and research use. The predictive reliability

of self-efficacy means that the DMSES UK can

be used to enable more effective targeting of selfmanagement interventions and clinical resources

to the individual patient. It has strong face validity

and is a reliable scale for use as an outcome

measure in research studies. Future research could

evaluate the predictive capacity of the DMSES

UK, in particular sub-groups of people with type 2

diabetes.

Validity and reliability of the DMSES UK scale 7

Clinicians have a tool available, which has

strong face validity, with both clinicians and

patients, to help identify in which areas of diabetes self-management a patients self-efficacy is

more or less secure. This will enable clinicians to

coach the patients into goal choice areas, where

new behavioural challenges are more likely to

be successful. Early success in new behavioural

challenges will lead to strengthening of self-efficacy

in more challenging goals over time.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the WDREUG,

the people with type 2 diabetes and the health care

professionals who have participated in this study.

Thanks are due to Professor Shortridge-Baggett

and Dr van der Bijl for their collaborative engagement with this UK validation study. The study was

funded by Diabetes UK and the UK Department of

Health NCCRCD programme.

References

Anderson, R.M., Funnell, M.M., Fitzgerald, A.T. and Marrero,

D.G. 2000: The diabetes empowerment scale: a measure of

psychosocial self-efficacy. Diabetes Care 23, 73943.

Bandura, A. 1977: Self-efficacy theory: towards a unifying

theory of behaviour change. Psychological Review 84,

191215.

Bandura, A. 1994: Self-efficacy. In Ramachaudran, V.S., editor,

Encyclopedia of human behavior. New York: Academic

Press, 7181.

Bandura, A. 1997: Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. New

York: Freeman.

Bandura, A. 2006: Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales.

In Pajares, F. and Urdan, T. editors, Self-efficacy beliefs of

adolescents. Charlotte NC: Information Age Publishing,

30737.

Bijl, V.J., Poelgeest-Eeltink, A.V. and Shortridge-Baggett, L.

1999: The psychometric properties of the diabetes

management self-efficacy scale for patients with type 2

diabetes mellitus. Journal of Advanced Nursing 30, 35259.

Dale, J., Caramlau, I., Sturt, J., Friede, T. and Walker, R. 2009:

Telephone peer-delivered intervention for diabetes

motivation and support: the telecare exploratory RCT.

Patient Education and Counselling 75, 9198.

Davies, M.J., Heller, S., Skinner, T.C., Campbell, M.J., Carey,

M.E., Cradock, S., Dallosso, H.M., Daly, H., Doherty, Y.,

Eaton, S., Fox, C., Oliver, L., Rantell, K., Rayman, G. and

Khunti, K. 2008: Effectiveness of the diabetes education

and self management for ongoing and newly diagnosed

(DESMOND) programme for people with newly

diagnosed type 2 diabetes: cluster randomised controlled

trial. BMJ 336, 49195.

Day, J.L., Bodmer, C.W. and Dunn, O.M. 1997: Development

of a questionnaire identifying factors responsible for

successful self-management of insulin-treated diabetes.

Diabetic Medicine 13, 56473.

Department of Health. 2002: The national service framework

for diabetes standards document. London: Department of

Health.

Department of Health. 2005: Structured patient education in

diabetes: report from the patient education working group,

2005. London: Department of Health.

Donaldson, L. 2003: Expert patients usher in a new era of

opportunity for the NHS. BMJ 326, 127980.

Farmer, A., Wade, A., French, D.P., Goyder, E., Kinmonth,

A.L. and Neil, A. 2005: The DiGEM rial protocol a

randomised controlled trial to determine the effect on

glycaemic control of different strategies of blood glucose

self-monitoring in people with type 2 diabetes

[ISRCTN47464659]. BMC Family Practice 6, 18.

Fisher, E.B., Thorpe, C.T., Devellis, B.M. and Devellis, R.F.

2007: Healthy coping, negative emotions, and diabetes

management: a systematic review and appraisal. Diabetes

Educator 33, 1080103.

Gillis, A.J. 1993: Determinants of health promoting lifestyle;

an integrative review. Journal of Advanced Nursing 18,

54553.

Guevara, J.P., Wolf, F.M., Grum, C.M. and Clark, N.M.

2003: Effects of educational interventions for self management of asthma in children and adolescents: systematic

review and meta-analysis. British Medical Journal 326,

1308309.

International Diabetes Federation. 2003: International standards

for diabetes education. Retrieved 30 April 2009 from

www.idf.org/webdata/docs/International%20standards.pdf

Lindenmeyer, A., Hearnshaw, H. and Sturt, J. 2007:

Assessment of the benefits of user involvement in health

research from the warwick diabetes care research user

group: a qualitative case study. Health Expectations 10,

26877.

Lloyd, C.E., Sturt, J., Johnson, M., Mughal, S., Collins, G. and

Barnett, A.H. 2008: Development of alternative methods

of data collection in South Asians with Type 2 diabetes.

Diabetic Medicine 25, 45562.

Lorig, K.R., Sobel, D.S., Stewart, A.L., Brown, B.W. Jr.,

Bandura, A., Ritter, P., Gonzalez, V.M., Laurent, D.D. and

Holman, H.R. 1999: Evidence suggesting that a chronic

disease self-management programme can improve health

status whilst reducing hospitalisation. A randomised trial.

Medical Care 37, 514.

McDowell, J., Courtney, M., Edwards, H. and ShortridgeBagget, H. 2005: Validation of the Australian/English

version of the diabetes management self-efficacy scale.

International Journal of Nursing Practice 11, 17784.

8 Jackie Sturt, Hilary Hearnshaw and Melanie Wakelin

Norris, S.L., Engelgau, M.M. and Venkat Narayan, K.M. 2001:

Effectiveness of self-management training in type 2

diabetes. A systematic review of randomised controlled

trials. Diabetes Care 24, 56187.

Pajares, F., Hartley, J. and Valiante, G. 2001: Response format

in writing self-efficacy assessment: greater discrimination

increases prediction. Measurement and Evaluation in

Counseling and Development 33, 21421.

Polonsky, W.H., Anderson, B.J., Lohrer, P.A., Welch, G.,

Jacobson, A.M., Aponte, J.E. and Schwartz, C.E. 1995:

Assessment of diabetes-related distress. Diabetes Care 18,

75460.

Sentcal, C., Nouwen, A. and White, D. 2000: Motivation

and dietary self-care in adults with diabetes: are selfefficacy and autonomous self-regulation complementary or competing constructs? Health Psychology 19,

45257.

Shortridge-Bagget, L.M. and van der Bijl, J.J. 2002:

Measurement of significant others self-efficacy in diabetes

management. In Sigma Theta Tau International

Conference, Brisbane.

Sniehotta, F.F., Scholzu, U. and Schwarzer, R. 2005: Bridging

the intention behaviour gap: planning, self-efficacy, and

action control in the adoption and maintenance of physical

exercise. Psychology and Health 20, 14360.

Sturt, J., Hearnshaw, H., Farmer, A., Dale, J. and Eldridge, S.

2006a: The diabetes manual trial protocol a cluster

randomized controlled trial of a self-management

intervention for type 2 diabetes [ISRCTN06315411].

BMC Family Practice 7.45.

Sturt, J., Taylor, H., Docherty, A., Dale, J. and Louise, T.

2006b: A psychological approach for providing selfmanagement education for people with type 2 diabetes:

the diabetes manual. BMC Family Practice 7.70.

Sturt, J.A., Whitlock, S., Fox, C., Hearnshaw, H., Farmer, A.J.,

Wakelin, M., Eldridge, S., Griffiths, F. and Dale, J. 2008:

Effects of the diabetes manual 1:1 structured education in

primary care. Diabetic Medicine 25, 72231.

Van Der Ven, N.C., Weinger, K., Yi, J., Pouwer, F., Ader, H.,

Van Der Ploeg, H.M. and Snoek, F.J. 2003: The confidence

in diabetes self-care scale: psychometric properties of a

new measure of diabetes-specific self-efficacy in Dutch and

US patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 26, 71318.

Welch, G., Weinger, K., Anderson, B. and Polonsky, W.H.

2003: Responsiveness of the problem areas in diabetes

(PAID) questionnaire. Diabetic Medicine 20, 6972.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Early Signs of AutismDocumento27 pagineEarly Signs of AutismErica Alejandra Schumacher100% (1)

- The Summary of Diabetes Self Care Activities Measure Results From 7 Studies and A Revised Scale PDFDocumento8 pagineThe Summary of Diabetes Self Care Activities Measure Results From 7 Studies and A Revised Scale PDFDiabetesBhNessuna valutazione finora

- Healthier Lifestyle, Behaviour ChangeDocumento4 pagineHealthier Lifestyle, Behaviour ChangeupelworopezaNessuna valutazione finora

- COCOMODocumento21 pagineCOCOMOanirban_surNessuna valutazione finora

- Form16 (2021-2022)Documento2 pagineForm16 (2021-2022)Anushka PoddarNessuna valutazione finora

- Nestlé Management Trainee ProgramDocumento10 pagineNestlé Management Trainee ProgramRiki Risandi100% (1)

- Responsibility MatrixDocumento6 pagineResponsibility MatrixRizky Bangkit100% (1)

- Project Report On Biodegradable Plates, Glasses, Food Container, Spoon Etc.Documento6 pagineProject Report On Biodegradable Plates, Glasses, Food Container, Spoon Etc.EIRI Board of Consultants and Publishers0% (1)

- Fundamentals of Plant BreedingDocumento190 pagineFundamentals of Plant BreedingDave SubiyantoNessuna valutazione finora

- Penicillin G Benzathine-Drug StudyDocumento2 paginePenicillin G Benzathine-Drug StudyDaisy Palisoc67% (3)

- Care of The Client Utilizing The Goal Attainment TheoryDocumento8 pagineCare of The Client Utilizing The Goal Attainment TheoryInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology100% (1)

- Diabetes Artigo EdDocumento15 pagineDiabetes Artigo EdEduarda CarvalhoNessuna valutazione finora

- Self EfficacyDocumento8 pagineSelf Efficacy130011035 RATNA YUNITA SARINessuna valutazione finora

- Poster Carozaramos 4Documento1 paginaPoster Carozaramos 4api-290348341Nessuna valutazione finora

- Assessing The ProblemDocumento10 pagineAssessing The ProblemKeyvoh KeymanNessuna valutazione finora

- Dia Care 2002 Pastors 608 13Documento6 pagineDia Care 2002 Pastors 608 13Isnar Nurul AlfiyahNessuna valutazione finora

- Perceived Barriers and Effective Strategies To Diabetic Self-ManagementDocumento18 paginePerceived Barriers and Effective Strategies To Diabetic Self-ManagementArceeJacobaHermosaNessuna valutazione finora

- A Study To Assess The Level of Coping Strategies Among The Patients With Chronic Diabetes Mellitus Admitted in Selected HospitalsDocumento9 pagineA Study To Assess The Level of Coping Strategies Among The Patients With Chronic Diabetes Mellitus Admitted in Selected HospitalsIJAR JOURNALNessuna valutazione finora

- Mediating The Effect of Self-Care Management InterventionDocumento13 pagineMediating The Effect of Self-Care Management InterventionDa TaoNessuna valutazione finora

- Association of Self-Efficacy and Self-Care With Glycemic Control in DiabetesDocumento7 pagineAssociation of Self-Efficacy and Self-Care With Glycemic Control in DiabetesSeptian M SNessuna valutazione finora

- Diabetes ManagementDocumento6 pagineDiabetes Managementapi-259018499Nessuna valutazione finora

- Upaya Pemberdayaan Kader Kesehatan Dalam Peningkatan Berbasis Konservasi LevineDocumento6 pagineUpaya Pemberdayaan Kader Kesehatan Dalam Peningkatan Berbasis Konservasi LevineDyan NittaRahayuNessuna valutazione finora

- The Validity and Reliability of The Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities Questionnaire: An Indonesian VersionDocumento12 pagineThe Validity and Reliability of The Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities Questionnaire: An Indonesian VersionPopi SopiahNessuna valutazione finora

- Optimal EngDocumento11 pagineOptimal EngIRENE ORTIZ LOPEZNessuna valutazione finora

- PHD Proposalmaterial 2Documento7 paginePHD Proposalmaterial 2ghaji jonathanNessuna valutazione finora

- Bibliography Journal On Diabetic FootDocumento3 pagineBibliography Journal On Diabetic FootCamille GraceNessuna valutazione finora

- Richardson Synthesis Summative 280613Documento13 pagineRichardson Synthesis Summative 280613api-217086261Nessuna valutazione finora

- Patient Education and CounselingDocumento9 paginePatient Education and CounselingJavi PatónNessuna valutazione finora

- JPHR 2021 2240Documento5 pagineJPHR 2021 2240Muhammad MulyadiNessuna valutazione finora

- The Influence of Complication Events On The Empowerment Selfcare of Diabetes Mellitus PatientsDocumento5 pagineThe Influence of Complication Events On The Empowerment Selfcare of Diabetes Mellitus PatientsInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Content ServerDocumento8 pagineContent ServerPaul CenabreNessuna valutazione finora

- Pamungkas2017 PDFDocumento17 paginePamungkas2017 PDFPaskalya eroNessuna valutazione finora

- Patient Education and CounselingDocumento8 paginePatient Education and CounselingSri WahyuniNessuna valutazione finora

- A Systematic Review On The Kap-O Framework For Diabetes Education and ResearchDocumento21 pagineA Systematic Review On The Kap-O Framework For Diabetes Education and ResearchToyour EternityNessuna valutazione finora

- Increasing Diabetes Self-Management Education in Community SettingsDocumento2 pagineIncreasing Diabetes Self-Management Education in Community Settingsmuhammad ade rivandy ridwanNessuna valutazione finora

- Group-Based Dietary Program Improves HypertensionDocumento14 pagineGroup-Based Dietary Program Improves HypertensionNur Fadillah B21741419601Nessuna valutazione finora

- Jurnal Self Management DM Literacy 4Documento8 pagineJurnal Self Management DM Literacy 4Rifa AinunNessuna valutazione finora

- Systematic Review Revised EditionDocumento43 pagineSystematic Review Revised EditionjunaidNessuna valutazione finora

- Conclusion and RecommendationDocumento3 pagineConclusion and RecommendationMarcelo MalabananNessuna valutazione finora

- Chronic Illnesses Are Becoming An Increasingly Serious Public Health Issue Across The WorldDocumento7 pagineChronic Illnesses Are Becoming An Increasingly Serious Public Health Issue Across The WorldHaneenNessuna valutazione finora

- Quality Improvement Project.Documento7 pagineQuality Improvement Project.rhinoNessuna valutazione finora

- Effectiveness of diabetes education and self-management programme at 3 yearsDocumento22 pagineEffectiveness of diabetes education and self-management programme at 3 yearsUlva HirataNessuna valutazione finora

- De Guzman Christelle Marie P. Dela Cruz Claire D. Assessment Shared Journal Reflection CP4Documento2 pagineDe Guzman Christelle Marie P. Dela Cruz Claire D. Assessment Shared Journal Reflection CP4Christelle Marie De GuzmanNessuna valutazione finora

- Low Carb For DiabetesDocumento6 pagineLow Carb For DiabetesChrisNessuna valutazione finora

- Arun ArticleDocumento8 pagineArun Articleslacker77725Nessuna valutazione finora

- 2965-Article Text-12063-3-10-20211018Documento7 pagine2965-Article Text-12063-3-10-20211018Nur Laili FitrianiNessuna valutazione finora

- Chronic Illnesses Are Becoming An Increasingly Serious Public Health Issue Across The WorldDocumento7 pagineChronic Illnesses Are Becoming An Increasingly Serious Public Health Issue Across The WorldHaneenNessuna valutazione finora

- The Impact of Orem's Self-CareDocumento9 pagineThe Impact of Orem's Self-CareRiski Official GamersNessuna valutazione finora

- Emagrecimento Determinantes ShowwwwDocumento41 pagineEmagrecimento Determinantes ShowwwwÉomer LanNessuna valutazione finora

- Lin 2012Documento7 pagineLin 2012Ferdy LainsamputtyNessuna valutazione finora

- Diabetes Distress Paper EfmjDocumento16 pagineDiabetes Distress Paper EfmjAhmed NabilNessuna valutazione finora

- King JournalClubDocumento7 pagineKing JournalClubTimothy Samuel KingNessuna valutazione finora

- Motivation Implementation of Hba1C Decrease in Patients Diabetes Mellitus (Riview Literature) Christianto NugrohoDocumento6 pagineMotivation Implementation of Hba1C Decrease in Patients Diabetes Mellitus (Riview Literature) Christianto Nugrohomarisa isahNessuna valutazione finora

- Nutrition Knowledge, Attitudes, and Self-Regulation As PDFDocumento9 pagineNutrition Knowledge, Attitudes, and Self-Regulation As PDFJoem cNessuna valutazione finora

- Running Head: Integrative Literature Review 1Documento20 pagineRunning Head: Integrative Literature Review 1api-456537311Nessuna valutazione finora

- Migraine and Body Mass Index Categories: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational StudiesDocumento14 pagineMigraine and Body Mass Index Categories: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational StudiesRetno ManggalihNessuna valutazione finora

- Caudill IntegrativereviewDocumento28 pagineCaudill Integrativereviewapi-453322312Nessuna valutazione finora

- Edinburgh Research Explorer: Pilot Study of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy For Irritable Bowel SyndromeDocumento25 pagineEdinburgh Research Explorer: Pilot Study of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy For Irritable Bowel SyndromeJuan Alberto GonzálezNessuna valutazione finora

- Nursing Agency Improves Diabetes Self-CareDocumento23 pagineNursing Agency Improves Diabetes Self-CareWisnu KhawirianNessuna valutazione finora

- International Journal of Diabetes and Clinical Research Ijdcr 8 134Documento7 pagineInternational Journal of Diabetes and Clinical Research Ijdcr 8 134Rio Raden Partotaruno TamaelaNessuna valutazione finora

- Effectiveness of Motivational Interviewing for Health BehaviorsDocumento11 pagineEffectiveness of Motivational Interviewing for Health BehaviorsPasca Liana MariaNessuna valutazione finora

- Instrumen Quality of Life WHOQOL-BREEFDocumento9 pagineInstrumen Quality of Life WHOQOL-BREEFSri Wulandari 15026760201Nessuna valutazione finora

- HMB Weight ManagementDocumento5 pagineHMB Weight ManagementJesse M. MassieNessuna valutazione finora

- BMC 2008Documento10 pagineBMC 2008Fadel TrianzahNessuna valutazione finora

- Perceptions, Attitudes, and Behaviors of Primary Care Providers Toward Obesity Management: A Qualitative StudyDocumento18 paginePerceptions, Attitudes, and Behaviors of Primary Care Providers Toward Obesity Management: A Qualitative StudyFitriani WidyastantiNessuna valutazione finora

- Impact of A Designed Self-Care Program On Selected Outcomes Among Patients Undergoing HemodialysisDocumento18 pagineImpact of A Designed Self-Care Program On Selected Outcomes Among Patients Undergoing HemodialysisImpact JournalsNessuna valutazione finora

- VA Diabetes Education Program Improves HbA1c & WeightDocumento8 pagineVA Diabetes Education Program Improves HbA1c & WeightNsafifahNessuna valutazione finora

- Dinamika Kelompok Tani SaiyoDocumento10 pagineDinamika Kelompok Tani SaiyoYoudz VoLvoc100% (1)

- Work Breakdown StructureDocumento9 pagineWork Breakdown StructureArif ForhadNessuna valutazione finora

- Kepuasan Kerja Petugas Kesehatan Di Instalasi Rawat Inap Rs Islam FaisalDocumento14 pagineKepuasan Kerja Petugas Kesehatan Di Instalasi Rawat Inap Rs Islam FaisalRizky BangkitNessuna valutazione finora

- Dinamika Kelompok Tani SaiyoDocumento10 pagineDinamika Kelompok Tani SaiyoYoudz VoLvoc100% (1)

- AdapRandomSearch4 05 2009Documento16 pagineAdapRandomSearch4 05 2009Meo Meo ConNessuna valutazione finora

- 1TA11813Documento8 pagine1TA11813Septy AmorrindaNessuna valutazione finora

- Effect of Parenting, School Environment, and Peers on Teen EQDocumento11 pagineEffect of Parenting, School Environment, and Peers on Teen EQRizky BangkitNessuna valutazione finora

- Simple Additive Weighting (SAW) MethodDocumento1 paginaSimple Additive Weighting (SAW) MethodRizky BangkitNessuna valutazione finora

- The Relationship Between Self Efficacy and Well Being in Stroke Survivors 2329 9096.1000159Documento10 pagineThe Relationship Between Self Efficacy and Well Being in Stroke Survivors 2329 9096.1000159anangdwiresdiantoNessuna valutazione finora

- LETOR: Benchmark Dataset For Research On Learning To Rank For Information RetrievalDocumento8 pagineLETOR: Benchmark Dataset For Research On Learning To Rank For Information RetrievalRizky BangkitNessuna valutazione finora

- User ManualDocumento193 pagineUser Manualcrazymax90Nessuna valutazione finora

- Perhitungan Manual Metode AHP RevisedDocumento16 paginePerhitungan Manual Metode AHP RevisedNana Rusmar100% (1)

- Edge Detection: Xy, and Y2, We Will Approximate - L (M+X, N+y) - L (M, N) - (L (M+X, N+y) - L (M, N) ) by The LinearDocumento25 pagineEdge Detection: Xy, and Y2, We Will Approximate - L (M+X, N+y) - L (M, N) - (L (M+X, N+y) - L (M, N) ) by The LinearRizky BangkitNessuna valutazione finora

- Worksheet - Solubility - Water As A SolventDocumento2 pagineWorksheet - Solubility - Water As A Solventben4657Nessuna valutazione finora

- Soni Clinic & Pathology Center Chanda: Address:-Front of TVS AgencyDocumento1 paginaSoni Clinic & Pathology Center Chanda: Address:-Front of TVS AgencyVishalNessuna valutazione finora

- Seizure Acute ManagementDocumento29 pagineSeizure Acute ManagementFridayana SekaiNessuna valutazione finora

- CH 23 PDFDocumento42 pagineCH 23 PDFkrishnaNessuna valutazione finora

- Food Sample Test For Procedure Observation InferenceDocumento2 pagineFood Sample Test For Procedure Observation InferenceMismah Binti Tassa YanaNessuna valutazione finora

- 2018 Nutrition Month ReportDocumento1 pagina2018 Nutrition Month ReportAnn RuizNessuna valutazione finora

- DaloDocumento2 pagineDalojosua tuisawauNessuna valutazione finora

- Frontier DL650 Maintenance Guide Ver 1.0Documento25 pagineFrontier DL650 Maintenance Guide Ver 1.0philippe raynalNessuna valutazione finora

- MSDS - ENTEL BatteryDocumento3 pagineMSDS - ENTEL BatteryChengNessuna valutazione finora

- Excipients As StabilizersDocumento7 pagineExcipients As StabilizersxdgvsdgNessuna valutazione finora

- As en 540-2002 Clinical Investigation of Medical Devices For Human SubjectsDocumento8 pagineAs en 540-2002 Clinical Investigation of Medical Devices For Human SubjectsSAI Global - APACNessuna valutazione finora

- CD - 15. Republic of The Philippines Vs Sunlife Assurance of CanadaDocumento2 pagineCD - 15. Republic of The Philippines Vs Sunlife Assurance of CanadaAlyssa Alee Angeles JacintoNessuna valutazione finora

- EMAAR HOUSING HVAC SYSTEM SPECIFICATIONSDocumento91 pagineEMAAR HOUSING HVAC SYSTEM SPECIFICATIONSBhuvan BajajNessuna valutazione finora

- BrochureDocumento2 pagineBrochureRajib DasNessuna valutazione finora

- Atlas Copco Generators: 15-360 kVA 15-300 KWDocumento10 pagineAtlas Copco Generators: 15-360 kVA 15-300 KWAyoub SolhiNessuna valutazione finora

- Deltair BrochureDocumento4 pagineDeltair BrochureForum PompieriiNessuna valutazione finora

- Rorschach y SuicidioDocumento17 pagineRorschach y SuicidioLaura SierraNessuna valutazione finora

- Dladla Effect 2013Documento231 pagineDladla Effect 2013TheDreamMNessuna valutazione finora

- Single Inlet Centrifugal FanDocumento43 pagineSingle Inlet Centrifugal Fan4uengineerNessuna valutazione finora

- Computed Tomography (CT) - BodyDocumento7 pagineComputed Tomography (CT) - Bodyfery oktoraNessuna valutazione finora

- Barangay Peace and Order and Public Safety Plan Bpops Annex ADocumento3 pagineBarangay Peace and Order and Public Safety Plan Bpops Annex AImee CorreaNessuna valutazione finora

- Calculate Size of Transformer / Fuse / Circuit Breaker: Connected Equipment To TransformerDocumento16 pagineCalculate Size of Transformer / Fuse / Circuit Breaker: Connected Equipment To TransformerHari OM MishraNessuna valutazione finora

- Bioreactor For Air Pollution ControlDocumento6 pagineBioreactor For Air Pollution Controlscarmathor90Nessuna valutazione finora

- 16 Point Msds Format As Per ISO-DIS11014 PDFDocumento8 pagine16 Point Msds Format As Per ISO-DIS11014 PDFAntony JebarajNessuna valutazione finora

- Nabertherm RHTH Tube Furnace SOPDocumento4 pagineNabertherm RHTH Tube Furnace SOPIyere PatrickNessuna valutazione finora