Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

01.21 McNeur (2011)

Caricato da

Maria Clara Iura SchafaschekDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

01.21 McNeur (2011)

Caricato da

Maria Clara Iura SchafaschekCopyright:

Formati disponibili

407561

JUH37510.1177/0096144211407561McNeurJournal of Urban History

Articles

The Swinish Multitude:

Controversies over

Hogs in Antebellum

New York City

Journal of Urban History

37(5) 639660

2011 SAGE Publications

Reprints and permission: http://www.

sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/0096144211407561

http://juh.sagepub.com

Catherine McNeur1

Abstract

In the first half of the nineteenth century, New Yorkers fought passionately over the presence

of hogs on their streets and in their city. New Yorks filthy streets had cultivated an informal

economy and a fertile environment for roaming creatures. The battlesboth physical and

legalreveal a city rife with class tensions. After decades of arguments, riots, and petitions,

cholera and the fear of other public health crises ultimately spelled the end for New Yorks

hogs. New York struggled during this period to improve municipal services while adapting to

a changing economy and rapid population growth. The fights between those for and against

hogs shaped New York Citys landscape and resulted in new rules for using public space a new

place for nature in the city.

Keywords

environmental history, public space, social conflict, animals, New York City

On Tuesday, April 5, 1825 two hog catchers entered the Eighth Ward of New York City. For the

first time in four years, free-roaming pigs were illegal in this northern neighborhood where their

owners riots had previously kept the hog law at bay.1 Conscious that disgruntled hog owners

might resist their efforts, the citys aldermen prepared accordingly. Four officers, including

Marshall Abner Curtis, who had weathered riots alongside dog catchers in the 1810s, accompanied the hog catchers.2 By the time the six men reached the upper end of Hudson Street, near

Vandam, their cart teemed with squealing swinish captives. Angry men and women had gathered

around thema crowd the newspapers referred to as a large mob of disorderly people. With

their demands for the return of the livestock unmet, the protestors got violent. Henry Bourden

an Irish laborer who lived in the Eighth Ward with his wife, four children, and likely several

pigsgrabbed a four-pound weight, perhaps a brick, and hurled it at the officers. He hit Abner

Curtis in the face, knocking him down onto the street. After the crowd had overtaken the hog

catchers and officers, they broke open the back of the wooden cart and let loose all of the hogs,

who quickly scampered off in different directions.3

1

Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA

Corresponding Author:

Catherine McNeur, Department of History, Yale University, P.O. Box 208324, New Haven, CT 06520-8324

Email: catherine.mcneur@gmail.com

Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at PORTLAND STATE UNIV on January 8, 2015

640

Journal of Urban History 37(5)

The Eighth Ward was changing. Wealthier residents had moved in and they demanded cleaner

streets free of swine foraging among the heaps of garbage. The northwestern suburbs of

Manhattan (todays Greenwich Village, West Village, and Tribeca) became especially attractive

to downtown residents during the Yellow Fever outbreak of 1822 after the city cordoned off the

denser neighborhoods on the southern tip of the island. Even after the restrictions were lifted,

many decided to stay and make the Eighth Ward their permanent home.

The working-class hog owners, who had lived in the area for years, felt that interlopers were

attacking their neighborhood and way of life. These Irish and African American laborers were

barely scraping by, and their livestock were an important source of both income and food. Yet

this was of little interest to those who did not own hogs and considered them a nuisance. A month

before the hog riot, some of these wealthier residents rallied together and petitioned the Common

Council to extend the boundaries of the hog law to include their ward. They planned to polish up

their streets, and that involved getting rid of the pigs that blocked their sidewalks. The aldermen

eagerly obliged.4

The 1825 hog riot that resulted was part of a larger string of physical and legal battles that

helped to shape the landscape of New York.5 The issue of free-roaming swine was divisive, and

the battles that ensued exposed a city rife with class tensions. Anti-hogites, or those against the

presence of loose hogs, contended that the animals impeded the progress, refinement, and modernity of New York. Pro-hogites, however, believed citizens had the right to utilize public spaces

as necessary in order to subsist.6 As New Yorks population swelled during the nineteenth century, these conflicting ideas of how public space ought to be used led to increasingly desperate

battles over whose vision should reign supreme.

Scholars have typically portrayed cities as social artifacts, in opposition to their rural or natural surroundings. Lewis Mumford, for instance, wistfully wrote that nature, except in a surviving landscape park, is scarcely to be found near the metropolis.7 Cities, however, are hybrid

spaces where human occupants have hardly conquered their environment, let alone separated

themselves from it. By examining the ways people fought over the urban environment, historians

can get an even fuller sense of the social dynamics that shaped cities. Attempts to remove

New Yorks hogs led to fierce debates and violent encounters about the citys character and the

rules governing its space. The politically contentious battles that ensued demonstrate how

changes to public space can have an extensive economic and environmental impact while also

redefining what it means to be urban.8

New Yorkers had been arguing about hogs for centuries. In 1640, the Dutch West India

Company complained that they had suffered great injury of cultivation and serious damage to

their holdings at the hands (or hooves) of hogs and goats. A decade later, a desperate Peter

Stuyvesant, the director-general of New Amsterdam, threatened to shoot down any hog found

rooting near the fort. The English who succeeded the Dutch also found it difficult to deal with

roaming swine and struggled to enforce impoundment laws and organize government-regulated

hunting of loose hogs on the streets.9

Hogs became an even bigger problem after the American Revolution. Following the war, the

citys population boomed as people moved in from the countryside and overseas. Hogs subsisted, for the most part, on the garbage that New Yorkers placed on the sidewalks and streets

outside of their homes and businesses. As the human population grew and garbage piled higher,

the hog population thrived. One 1820 estimate suggested that there were twenty thousand hogs

in the settled parts of Manhattan, or approximately one hog for every five humans in the city.10

By the 1810s, the controversy over hogs had become a hot topic for New Yorkers, revealing

friction between wealthier and poorer neighbors. While hogs had been owned by residents of all

classes in colonial New York, in the early nineteenth century they were typically the property of

Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at PORTLAND STATE UNIV on January 8, 2015

641

McNeur

poorer city residents. Wealthy and middle-class New Yorkers had been able to abandon gardening

and raising livestock in exchange for purchasing their food with cash at their local markets.

Poorer New Yorkers with smaller wages had a harder time making that transition.11 In consequence,

as these issues with swine intensified, they began to reflect growing class tensions in the city.

Hogs role as livestock did not help their situation. They were not coddled or praised as pets

such as dogs were. While certainly some of their owners bonded with them, their potential to be

eaten or sold probably helped to limit the depth of that bond. Potential bourgeois allies were less

likely to sympathize with the plight of the urban hog as they might with other animal wanderers like

cats and dogs, since they did not have similar creatures at home to compare. With farms getting

pushed further and further from the citys center, hogs increasingly seemed to anti-hogites like an

unwelcome presence in what should have been a human-centered environment. At best they were

seen as a food source, at worst as stubborn, filthy impediments on streets and sidewalks.

In their anonymous letters to newspapers, anti-hogites of the 1810s and 1820s routinely drew

parallels between the pigs and their owners, using Edmund Burkes phrase the swinish multitude to describe both populations.12 For these authors, New Yorks urban hogs were as much of

an Other as the Irish immigrants and African Americans who owned them. Pigs association

with the citys lower classes led to many vicious, tongue-in-cheek poems and letters by critics

who saw the animals and their owners as interchangeable.13 When an author described a hog as

the filthiest part of the brutes, his disdain for the citys poor shined through.14 Hogs, long considered to be among the lowliest of farm animals because of their ravenous, greedy behavior,

were ripe for insults. While wealthier New Yorkers were perhaps hesitant to insult their poorer

neighbors directly, insulting their animals provided an outlet for airing class tensions. Through

these comparisons, whether drawn in humor or anger, anti-hogite writers emphasized the ridiculousness of allowing outsidersbase pigs and their similarly base ownersto run their city.

Yet when Europeans visited the city, their criticism of the roaming hogs condemned all

New Yorkers, not just the poor who owned them. When Charles Henry Wilson visited from

England in 1819, he found the city to be miserably dirty with innumerable hungry pigs of all

sizes and complexions, great and small beasts prowling in grunting ferocity, and in themselves so

great a nuisance, that would arouse the indignation of any but Americans.15 Worried about such

reactions, anti-hogites pleaded with the Council to refine the city. Discussing a vacant lot of land

filled with house rubbish, swine, cattle, and beggars, a neighbor appealed to the city to clean it

up: [the Common Councils] interference becomes doubly urgent, in this instance, from the

consideration, that the nuisance above mentioned exists in the section of town which is most

frequented by our citizens, and by strangers who visit New York.16 The citys image was at

stake (see Figure 1). The New York anti-pig constituency frequently referred to the city as being

disgraced by the presence of the animals. These residents were concerned about the influence

of swine on the identity of their city.17 To visitors and local anti-hogites alike, the hogs symbolized all that was backwards in New York. They represented the city governments inability to

exact change and promote the progress of the city. When the anti-hogites complained about hogs,

they were also in many ways complaining about the undesirable classes living in their city that

imposed on their public space and municipal government.18

The hog owners, however, saw these issues more in terms of survival than in terms of modernity or progress. Whereas in the eighteenth century laborers lived and ate in the homes of master

craftsmen, with the growth of wage labor most of these men had to find separate housing and pay

rent.19 Food was rarely cheap and as the decades went on prices became less predictable.20 Jobs

for day laborers were hardly stable, often seasonal, and completely dependent on weather and

economic conditions. Municipal welfare programs, while helpful in assisting some of the poor

with food and fuel, could not keep up with New Yorks ballooning population in the early nineteenth

Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at PORTLAND STATE UNIV on January 8, 2015

642

Journal of Urban History 37(5)

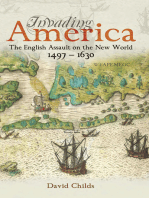

Figure 1. In this image by a nineteenth-century tourist, hogs are depicted intermingling with pedestrians

and traffic on Broadway in plain sight of City Hall.

Brodway-Gatan Och Rdhuset i New York, 1824. Aquatint by Carl Fredrik Akrell based on etching by Axel Klinckowstrm (Metropolitan Museum of Art).

century.21 During periods of economic crisis, such as after the War of 1812, alternative sources

of income and food were especially crucial.

New Yorks laboring poor used hogs as a cheap and efficient way to make ends meet. When

the hog owners argued for the right to keep their livestock, they insisted that hogs allowed the

poor to pay their rents and supply their families with animal food, during the winter. By selling

a pig or two, they were able to procure some other articles necessary for their comfort and convenience. They pleaded that without their livestock, they would be forced to rely on the charity

of the city and become a public burden.22

Hogs could be left to take care of themselves on the street, finding free food in the gutters of

the city. The streets essentially served as an urban commons. While New York, unlike Boston,

lacked an official commons, its residents and their animals had created a de facto substitute.

Refuse mainly consisted of food-based items, such as offal and kitchen scraps, so the hogs could

essentially find their entire days diet within a few blocks of their residence. These urban foragers, who could be summoned by name, would apparently wander home at night to sleep in their

owners backyards or near the front stoop.23

The pro-hogites argued in petitions to the city that swine played an important role in cleaning

the streets of garbage. Since the city did not have the resources to supply enough street sweepers

to collect trash, hog owners contended that sanitation and public health problems actually would

worsen without swine to keep them under control. Pigs were our best scavengers, as they

instantly devour all fish guts, garbage, and offal of every kind, which is suffered to remain during

the summer months, [and] would be very offensive and might very probably be injurious to the

health of the inhabitants. Garbage collecting in the poorer neighborhoods was irregular at best,

and allowing hogs to forage was one method for removing trash and preserving the health of the

most vulnerable residents.24

Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at PORTLAND STATE UNIV on January 8, 2015

643

McNeur

The anti-hogites countered that the municipal government ought to fund and regulate street

cleaning more effectively, creating jobs for people, not swine. Many anti-hogites believed that

taking care of the streets would solve multiple problems. In 1809, a friend to order and improvement wrote to the Republican Watch-Tower pleading with the city to get rid of the trash so that

the hogs would disappear.25 If the city would just clean the streets, the hogs would have less to

subsist on and the owners would essentially be forced to take them off the street and either give

up the hog business or find alternative food sources for their creatures. Critics tied the existence

of hogs to a chaotic city where neither the government nor the citizens had control of the situation. With the growth in urbanization during this period, many residents hoped the city would

evolve into a more organized, manageable environment. If progress for anti-hogites meant the

municipal government maintaining control over its nuisances, pigs stubbornly grunted in

resistance.26

Hogs also disrupted city life by making the roads unfit for driving over in wagons and carts

due to their constant rooting. They used their snouts to dig up cobblestones and other materials

used for pavements, often causing traffic disruptions and accidents, not to mention muddy holes

for pedestrians to dodge. In 1812 the Common Council noted that pigs were tearing apart a sidewalk near the Battery, one of the more prestigious residential neighborhoods at the time and a

popular tourist destination: Every description of filth is there deposited & the swine by rooting

up the ground & wallowing there in the mire, make the passage to the Battery from Broadway

not only very unsightly but very offensive.27 As the city became more populous, the number of

problems and severity of the accidents only increased. Horses would either get scared by or

stumble over pigs loitering in the streets, causing their carriages to tip over, often injuring passengers and bystanders.28

Anti-hogites also complained about the danger hogs posed to public health. Swine were

closely tied to the filth and unpleasant smells that characterized the streets and public places of

the city. Hogs and garbage, after all, went hand in hand. The nineteenth-century medical community generally believed that the offensive smell of the animals, their exhalations, and their

environs aided epidemics. After each outbreak of yellow fever and cholera, complaints about

hogs increased in number in both newspaper articles and letters to the government. New Yorkers

even blamed mundane aches and illnesses on the hogs. It was not uncommon for those suffering

from headaches and nausea to accuse their neighbors fondness for swine.29

Anti-hogites saw the threat of these urban hogs to be even greater because they could turn up

on their dinner plates. Ham and pork, as well as other porcine products, were staples in the diets

of Americansrich and poorin the early nineteenth century. Unlike cows or goats, hogs

required little attention from their owners. Butchers and consumers could easily preserve pork

through salting and smoking, which was an enormous advantage since refrigeration was both

difficult and expensive. Not only were hog owners able to eat their street hogs, they could also

sell them to the butchers of the city. Anti-hogites often complained of the potential dangers of

eating these walking sewers that regularly consumed the offal and refuse left on the streets.30

One writer for The Evening Post claimed that

when they become diseased, from high feeding on dead cats and the vermin in the gutters,

or any other cause, they soon find their way to our butchers stalls. Knowing this may be

the case, if in fact it is not, many people of my acquaintance whose stomachs are rather

squeamish, would as soon taste a broiled rat as the finest looking griskin or roaster that

can be brought to the table.31

For health reasons, many New Yorkers who had the choice preferred to eat the pricier, countryraised hogs from Long Island and New Jersey.

Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at PORTLAND STATE UNIV on January 8, 2015

644

Journal of Urban History 37(5)

Anti-hogites found that one of the most effective ways to enrage votersmore effective perhaps than complaining of objectionable meatwas to expose the danger hogs posed to women

and girls, a tactic that started to appear in the newspapers in 1815. While boys mischievously

rode hogs down the streets and men caned hogs to get them to move, women and girls were more

often attacked by the creatures.32 One observer witnessed a bristly invader, in his precipitate

retreat across the pavement, upset a lady in full dress for a party, and landed her broad-side in

the filth of the gutter! The result was, no bones were broken; but her dress so soiled as to require

an entire change.33 The roles of women and girls remained almost constant in the anecdotes

used by those pleading for the removal of the swine. Women were thrown off their feet into mud

puddles and little girls lives were threatened by angry sows. Through tales that were likely exaggerated for dramatic effect, authors invited the men of the city and specifically the aldermen to

be valiant heroes and make the city safe for genteel women-folk.

Yet pro-hogites would perhaps argue that the women in these stories represented only a specific population of the city. Many working-class women owned and cared for the hogs that were

villains of these tales. The hogs contributed to their household economy and female members of

the family were likely those who tended the swine when necessary. These women were also

actively involved in protesting the laws and rioting when necessary. While anti-hogites might

argue that all women were threatened by the quadrupeds, they were not accounting for those who

relied on them.34

These arguments between anti-hogites and pro-hogites had fully matured by the mid-1810s when

the hogs had become so numerous that their presence could no longer be ignored. Following the War

of 1812, the city fell into an economic slump. Facing unemployment or underemployment, many

of the poorest New Yorkers scraped by using alternative means of subsistence and income. At the

same time, the citys population was growing rapidly and stylish neighborhoods were pushing into

the outskirts of town where these working-class New Yorkers lived. This clashing of neighborhoods

and classes, along with the rising number of hogs, brought the conflict to a boiling point.35

In November 1816, Abijah Hammond, one of New Yorks wealthiest landowners and merchants, rallied a group of approximately two hundred anti-hogites and submitted a petition to the

Common Council calling for the removal of all free-roaming swine from the streets.36 The

Council considered drafting a law but postponed voting on it twice: the first time because it

would oblige the poor owners to kill off their herds before the usual butchering season in the

fall; the second because it would jeopardize their own political careers if discussed before the

April elections. That May, however, the Council returned to the issue and resolved to finally

be done with pigs.37 Hog owners got word of the Councils intentions and united quickly under

the leadership of Adam Marshall, an African American chimney sweep. In merely two days, they

drew up a petition containing eighty-seven signatures and marks of both men and women, which

pled with the city to pity the poor and allow the hogs to remain, as they were a necessary

resource for the destitute.38 The Evening Post reported that the petitioners read the remonstrance

in such a dramatic fashion that the aldermen felt the need to adjourn for a week.39

Hearing about this display, the anti-hogites belittled the pro-hogite efforts in the newspapers.

One author mocked the petition as being signed, or at least marked by the principal master

chimney sweeps, who generally keep droves of hogs for our amusement.40 By mentioning the

chimney sweeps, this writer intended to tell readers that Marshall and the other petitioners were

African American, as chimney sweeping was commonly known to be an African American

occupation. Pro-hogites, however, were mainly united by their economic status as unemployed

or unskilled laborers, rather than by their race. Hog owners were typically recent Irish or English

immigrants, as well as African Americans. The authors invocation of chimney sweeps, however, helped to emphasize the outsider status of pro-hogites. Prior to the 1821 revision of the

Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at PORTLAND STATE UNIV on January 8, 2015

645

McNeur

New York State constitution, African Americans had the same voting rights as all New Yorkers.

It was typical to find men such as Adam Marshall actively involved in petitioning the Common

Council to protect their and other working-class New Yorkers interests.41 Yet, in the eyes of

anti-hogites, Marshall and the other hog owners had little right to influence the aldermen and, in

doing so, dictate how public space should be used.

When the Council reconvened on May 27 and avoided the contentious hog law topic, the

anti-hogites used humor to criticize what they saw as the impotence of the government. One

writer remarked that in battling the government, the hogs and, by implication, their owners had

kept their ground, grunting a sturdy defiance.42 The pro-hogites seemed to have the Common

Councils ear.

The aldermen waited for the dust to settle before they debated the proposed law a month

later. The document stipulated that hogs running at large would be impounded and their owners

would pay ten dollars plus costs to recover their property. This was an exceptionally steep fine

considering the average artisan earned approximately one dollar per day.43 The law was defeated

by four votes only to be considered again that October at the behest of countless anti-hogite

constituents. This time the Council passed the ordinance the same day it was proposed, leaving

the pro-hogites with no time to assemble and draw up another petition. The aldermen scheduled

the law to take effect January 1, 1818. In the meanwhile the anti-hogites celebrated their longawaited success.44

The pro-hogites, however, fretted about the implications of this new law. Adam Marshall

again rallied his hog-owning compatriots to sign a petition calling for the city to repeal the law,

but they were less than successful.45 Once more, the anti-hogite press ridiculed the efforts of a

black man and chimney sweep to challenge common decency.46 But Marshall was not

deterred and tried again on behalf of the pro-hogites, presenting a third petition to the Common

Council just a month after the law had taken effect. This document was much more substantial

than the petitions they had presented before, containing 140 signatures of only white men, and

rolling out to be nearly five feet long. Marshall, though African American himself, likely felt he

could be more effective and avoid the predictable ridicule of the press by excluding African

Americans and women from the list. The petitioners also responded to the criticism in the newspapers by including only signatures and no marks, which had earlier indicated the illiteracy of

some of their supporters. Addressing the especially unfair nature of the law that allowed private

individuals to take pigs off the streets in exchange for a reward, the petitioners claimed that

Unjust and rapacious men have prowled through several parts of the upper wards, and under

colour of this Law seized on the property of the poor, and even appropriated it to their own uses.

The city had essentially let loose a swarm of informers upon the defenseless poor.47 After this

petition and another were read before the Council, the persuaded aldermen repealed the law.48

Anti-hogites responded in kind, mourning the repeal and calling on voters to oust the aldermen at the next election. One poet, angered by the repeal, mused that the rulers of the city were

four-legged. He wrote,

But now the hogs,

Those grunting dogs,

Have made their sway complete;

A voice they have

In Council grave,

And rule in evry street.49

Anti-hogites returned to publishing satirical and humorous pieces in the newspapers ridiculing

the governments friendliness toward swine while pleading with the city to reissue a strict hog

Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at PORTLAND STATE UNIV on January 8, 2015

646

Journal of Urban History 37(5)

law. The author of the poem again equated the pro-hogites with their livestock, bemoaning the

power the poor had in influencing the city government.

Frustrated by the nonpartisan nature of the debates, one critic suggested designating the

ticket for aldermen and assistants that contains the names of such as are in favor of the hogs as

The Hog Ticket at the upcoming municipal election.50 There were certainly more Republican

aldermen voting for the repeal of the hog law than Federalists, but the division was more geographic than political. Aldermen and assistant aldermen from the outer wards typically voted

pro-hogite. Representing wards with lower land values, these aldermen counted many hog owners among their constituents. In the post-war economy with limited municipal resources for

welfare and many constituents struggling, taking away their wards hogs would have probably

caused more immediate problems than it would have solved.51

While the aldermen attempted to balance the needs of the citys destitute with the demands of

the increasingly vocal anti-hogite faction, Mayor Cadwallader D. Colden considered himself

above the fray. Unlike the aldermen, Colden was appointed by the governor rather than elected

and therefore not subject to the political pressure of constituents. Descended from an elite New

York family, Colden was solidly anti-hog. In 1818, soon after he took office, Colden decided to

use his position as judge of the Court of General Sessions to subvert the Common Councils

stalemate by calling a grand jury to hear evidence on urban pig-keeping. The jury returned an

indictment charging two artisans for the nuisance of keeping hogs on the street.52 One defendant

offered no defense and was quickly convicted and charged a nominal fee, but the other, Christian

Harriet, declared his innocence and hired lawyers, thereby sending the case to trial.

Mayor Colden hoped The People vs. Christian Harriet would be the legal end for the citys

roaming pigs. Harriets lawyers, however, claimed that he had the right to keep pigs in the

streets, as it was a practice of immemorial duration and our ancestors had never been troubled

with any excessive notions of delicacy on the subject. The attorneys pled with the jury to recognize the importance of the pigs, as their exile would cause the poor to be driven deeper into

poverty. They argued the case should be dismissed as the Council had repealed the law earlier

that year. Mr. Van Wyck, the prosecutor, and Mayor Colden, the judge, argued that despite the

absence of a municipal law, the city was still held to English common law precedents against

nuisances. Hogs, regardless of their benefit to the poor, qualified as a nuisance, which Colden

defined as an offence against the public order and economical regimen of the state, and an

annoyance to the public. Apparently Coldens public did not include the hog owners who

depended so dearly on these animals. By declaring loose hogs to be a nuisance, Colden was

unleashing the authority of the city to limit the hog owners property rights. Nuisance law was

one of the primary ways nineteenth-century cities exerted control over private property in order

to protect public welfare, however that might be defined.53 Responding to the defenses claim

that barring pigs from the streets would injure the poor, the mayor declared, Why, gentlemen!

Must we feed the poor at the expense of human flesh? He played on the fears that loose hogs

were not only a nuisance but also a threat to the welfare of the citys women and children. With

the mayors urging, the jury found Harriet guilty.54

The People vs. Christian Harriet set a precedent that was followed for at least two years after

the case. Instead of struggling to pass laws against all pig owners in general, the prosecutors

focused on indicting random, individual offenders for their negligence.55 The anti-hogites praised

the efforts of the courts in newspaper articles and hoped that the cases would have a significant

impact.56 The mayor had used his position as judge to circumvent the Common Councils deadlock. As one newspaper put it, we must look to our courts for the remedy; it is considered too

unpopular for the corporation to meddle with it.57 Mayor Colden found this to be the easiest way

to avoid dealing with petitioners and voters who did not support his vision for a pig-free city.

Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at PORTLAND STATE UNIV on January 8, 2015

647

McNeur

After three years, it had become apparent that the hog owners had not been frightened into

compliance by the threat of indictment. In 1821 a new mayor, Stephen Allen, took office, ready

to tackle the hog problem. Realizing that Coldens tactic had been unsuccessful, Allen brought

the issue back before the Common Council. The Council then passed a law that required all pigs

collected on the street be brought to the Almshouse where they would be served for dinner.58

Though the law was officially on the books, little was done to actually enforce it. A few antihogites wrote to the newspapers a month later pleading with the city to take action, claiming that

unless [the aldermen] wish to make fools of themselves and expose themselves to the contempt

and ridicule of the public, they will cause all their laws to be strictly enforced.59 Determined to

make the ordinance effective, the Common Council resolved that it be carried into full operation against the offenders.60

A mere four weeks later, the Council once again ran into problems. The Almshouse

Commissioners announced that they had tried to collect the hogs, but the hog catchers had been

violently resisted by the owners.61 Mayor Allen called the collectors together a few weeks later and

threatened that they either execute the law or forfeit their licenses. When the African American

hog catchers resumed their tasks later that week, they were immediately resisted by hundreds of

hog owners. Locals assaulted the hog catchers with mud, rotten food, hot water, and broomsticks.

A riot had begun.62 The rioters were a diverse group of women and men, mainly made up of

working-class Irish and African Americans. One of the possible reasons hog owners resorted to

violence was perhaps because a large number of themnamely, the African Americanshad lost

the ability to use more customary means of political protest, such as petitioning, with the restriction

of their suffrage under the 1821 New York State constitution.63 In response to the riot, the Council

limited the hog law so that it excluded the outer wards where resistance was particularly strong.

Anti-hogites belittled the riot as a feeble attempt to oppose the execution of this salutary

ordinance.64 Feeble or not, the hog owners were successful. By April 1822, the papers noted

that the Common Council indulged the hog owners who openly disregarded the ordinance, and

set it at defiance.65 The editors of the Evening Post complained that pigs were still found trampling through piles of garbage on the streets a year later in 1823, notwithstanding the prohibitions against them.66 The law was as good as dead.

When the city tried to reinvigorate its efforts to collect hogs in 1825, the resistance of the prohogites remained strong. The hog catchers were so effectively blocked in the Eighth Ward by

Henry Bourden and his neighbors that the law was again considered obsolete.67 Thomas F.

DeVoe, a butcher, wrote that he had witnessed many scrimmages that year where the negro

hog-catchers, and also the officers who attended them, were either cheated out of their prey, or

obliged entirely to desist, . . . [and] almost every woman, to a man, was joined together for common protection in resisting their favorites from becoming public property.68 Additional riots

occurred in 1826, 1830, and 1832 following the same pattern with several hundred people emerging each time to block the passage of the hogcart by whatever means necessary. While the antihogites continued to complain about the citys inability to implement the laws, the pig owners

had successfully impeded the city from enforcing them.69

And then in 1832 cholera struck. The city tried to prevent its spread by cleaning up public

spaces and minimizing nuisances. In fact, it was just that zeal to purify the streets that led to a

sweep through the city to remove hogs in 1832 and a subsequent hog riot, which was hardly

noticed by the newspapers amid all of the panic over the disease. Fear of the epidemics return

continued to inspire attention to street sanitation during the summers of the 1830s and 1840s, and

the roaming hog population slowly began to diminish.70 Tourists would still mock the conditions

of the streets, but anti-hogites stopped complaining as loudly and frequently in the newspapers

and government proceedings.71 The pigs were beginning to make an exit.

Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at PORTLAND STATE UNIV on January 8, 2015

648

Journal of Urban History 37(5)

It would not be until 1849 that the streets in the developed areas of Manhattan would officially

be hog-free. After the start of the cholera epidemic that year, the police, empowered by the Board

of Healths Sanitory [sic] Committee, went on a campaign to flush the grunting swine out of the

densest parts of the city. The captains of the police districts were instructed to remove all hogs to

the public pound with twenty-four hours notice.72 Just four years earlier, New York had established its first full-time professional police force. These men were, to an extent, responsible for

dealing with neighborhood nuisances. In the citys past attempts to eliminate its swinish residents, the mayor and aldermen passed responsibility on to departments and institutions, such as

the Almshouse, that lacked the ability to successfully enforce the law. The professional police

force made all the difference. Though the owners would not let go of their pigs without a fight,

the professional police were immediately more effective. After decades of difficulty, the city

finally had the ability to enforce the hog law.

The cholera outbreaks had ultimately sealed the free-roaming hogs fate. By June the police

had moved between five and six thousand swine into the northern part of the island. Cholera

seemed to follow the swine, striking residents of the more rural wards later that summer. Horace

Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune, who had recently lost his son to cholera, erroneously

blamed the epidemic on the arrival uptown of twenty thousand hogs.73 The first case of cholera

that year occurred at 20 Orange Street in the midst of Five Points, a blighted neighborhood where

many of the residents owned swine. A building just two doors down from the tenement had a

remarkable 106 hogs. The people who first got cholera even had a spoiled ham set out on their

makeshift table.74 While contaminated water was at the root of the epidemic, health officials

targeted the sanitation issues of the city more generally, including the street-wandering swine.75

The city had become so dense and its municipal serviceswhether water, sanitation, or support for the poorso lacking that epidemics such as cholera could thrive and affect large portions of the population. For several decades anti-hogites had been crafting arguments to convince

the municipal government to take action and eliminate hogs from the streets, but in the end a

public health crisis was actually what made the difference. Too many lives were at risk and

though we now know that the pigs had little to do with the outbreak, it seemed very possible to

the terrified city dwellers that they were in part to blame. In the hysteria that followed, the laws

finally stuck. Municipal officers and police attacked the general sanitation problems in full force.

While in the end they were only able to address a fraction of the public health issues facing the

city, they did succeed in clearing New Yorks streets of free-roaming hogs.

The fight was far from over, however. In the 1840s, anti-hogites began voicing complaints

about the growing number of piggeries, or property with penned hogs, in the upper reaches of the

city.76 These establishments existed mainly between 50th and 70th Streets in the center of the

islanda rocky area that locals often referred to as Hogtown or Pigtown. The piggery owners likely sold their hogs to the large-scale slaughterhouses that were built just to their south in

the 40s, as well as to local butchers. These butcher shops served their surrounding communities

and were an important source of cheap meat in poorer neighborhoods that were miles away

from the public markets.77

Piggeries were owned primarily by Irish immigrants, though Germans and the occasional

African American tried their hand at the business as well. While most owners of free-roaming

hogs in decades past used the animals to supplement their income, piggery owners made hog

fattening and selling their primary trade. There were other ways to make money in this industry

too. The piggery owners collected or paid scavengers to collect offal, bones, and swill from

slaughterhouses, hotel restaurants, and the streets. They took these materials that were otherwise

considered trash and boiled them in caldrons on their property. They then sold the fat to tallow

chandlers and soap makers and the bones to sugar refiners, and fed the remaining slop to their

hogs. The smells that rose from the offal- and bone-boiling cauldrons, more than anything else,

Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at PORTLAND STATE UNIV on January 8, 2015

649

McNeur

enraged the senses of downtown New Yorkers traveling through the northern reaches of

the city.78

The land purchased for the creation of Central Park included many of these piggeries. When

Frederick Law Olmsted took his first tour of the park in 1857, he complained that the low

grounds were steeped in [the] overflow and mash of pig sties, slaughterhouses and bone boiling

works and the stench was sickening.79 Most of the complaints lodged against the piggeries had

to do with the extensive smells the area produced, scattering the seeds of disease and death.

With the development of Central Park came a rush of real estate investors interested in profiting

from these once marginal lands. Once again, the swine and their odors would have to go.80

The social status and ethnicity of the piggery owners were not lost on their critics. A writer

from the New York Times described the neighborhood as a group of shanties in which the pigs

and the Patricks lie down together while little ones of Celtic and swinish origin lie miscellaneously, with billy-goats here and there interspersed.81 The closeness of the animals and their

owners emphasized the perceived depravity and savageness of the area and its residents.

Descriptions such as these only helped to fuel Nativist resentment of the Irish in New York.

Critics and reformers believed the piggeries were inappropriate in an increasingly refined city

and their odoriferous threat to public health should have sealed their fate.

Political stalemates led to the continued presence of piggeries in the upper wards. By the

1850s the pro-hogite and anti-hogite constituencies had shifted. Pro-hogites, or piggery owners,

were still made up of poorer Irish immigrants, but there were fewer African Americans and more

Germans than earlier in the century. In the Common Council, the division between those for and

against urban hogs also shifted, reflecting the starker partisan and ethnic divide in the city as a

whole. Tammany Democrats routinely sided with pro-hogites while Whigs and Nativists came

out against hogs and their Irish owners.

The heated political rancor over hogs was especially evident in 1854 when the Board of

Councilmen passed an ordinance prohibiting swine below 59th Street, with a fine of two dollars

per day per swine. In a debate about improving neighborhoods and removing piggeries, the councilmen representing the affected wards were defensive. Councilman Bryan McCahill, a Tammany

Democrat of the Nineteenth Ward, who depended on the Irish voters,

denounced those who favored such a proceeding as aristocrats, who, when they moved

into the Nineteenth Ward were so poor that they were glad to get a residence near a pigsty. Now, after they had been Aldermen and Councilmen for a year of two, they had

become wealthy and their refined noses couldnt stand the smell. He claimed that the

Nineteenth was one of the most healthful wards in the City, and that the Board had no right

to drive the pigs out of his Ward.

On the other side of the argument was Councilman John C. Wandell, a commercial merchant

representing the Twenty-Second Ward, who saw the pigsties as nuisances: The Twenty-second

Ward was improving rapidly, and the people there wished to make it a pleasant residence for

those doing business down town. Real estate values were a prime factor in both McCahills and

Wandells arguments. As the uptown neighborhoods around Central Park were rising in value,

the piggeries were becoming more of an issue. After an hour of fighting, the Council decided to

remove the pigs. The ordinance seems to have been barely enforced, however, likely due to a

combination of poor funding and pressure from Democratic aldermen who counted piggery owners among their constituents.82

In 1859, when Daniel Delavan took office as city inspector, he took direct measures to transform the northern wards. He initiated a resolution to ban piggeries, bone boiling, and offal boiling south of 86th Street. As soon as the Commissioners of Health approved the resolution, the

Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at PORTLAND STATE UNIV on January 8, 2015

650

Journal of Urban History 37(5)

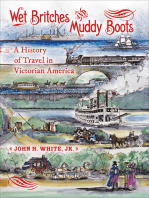

Figure 2. While the city inspector and police considered the Piggery War to be a success, the process

of rounding up the hogs was anything but easy.

Frank Leslies Illustrated Newspaper, August 13, 1859.

Piggery War began. Delavan seemingly ignored the political strife that had kept previous city

inspectors from acting on the piggeries and, in the process, stirred up a hornets nest of politicians who warned him to postpone action lest they lose votes from the Irish Democrats in the

upper wards. Though Delavan himself was a Tammany Democrat, he nevertheless moved forward with his agenda and began the process of full-scale hog removal.83

Delavan sent Richard Downing, superintendent of sanitary inspection, along with fifty-seven

inspectors and twenty-nine policemen on a tour of Hogtown. They visited each piggery, ready to

confront the notoriously vicious guard dogs and their potentially riotous owners. Instead, they

were met mainly by a good deal of loud talk and grumbling . . . accompanied by the deepest bass

grunting of the hogs.84 Perhaps the owners saw their removal as imminent or maybe the gang of

armed police and inspectors had sufficiently intimidated them. Downing and his men gave the

owners three days notice to get rid of their hogs and remove the associated structures (cauldrons,

pens, sheds, etc.) before they would return to tear everything down and drive the hogs to the

pound. The piggery owners had to act quickly to either relocate their animals or sell them to a

butcher.

When the police and health inspectors returned, they came armed with guns, clubs, pickaxes,

and crowbars (Figure 2). While residents did what they could to hide the remaining hogs

sometimes concealing them under beds and linensthe police were persistent and successful.

Hogs were driven to the pounds, pens torn down, cauldrons carted off, and the property covered

in lime to purify the area of its pestiferous qualities.85

The newspapers used war metaphors excessively, describing the police and sanitary officers

as an army of expulsion and their opponents as members of the pork army. They even drew

parallels to the recent Crimean War in Europe. With public health arguments on their side and a

veritable army of professional police, city officials and anti-hogites no longer felt it necessary to

debate whether hogs were a nuisance or a public good. The issue seemed much more black and

white since lives were at stake. Journalists portrayed the piggery closures as a battle for the

Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at PORTLAND STATE UNIV on January 8, 2015

651

McNeur

protection of the citys health and prosperity. In almost every article, authors described the

Piggery War in triumphant terms. The police and health inspectors were equated with war heroes,

while the piggery owners were described as backwards, stubborn, and defiant.86 Ironically, it was

a war with little violence at all.

Perhaps one of the most defiant members of the pork army was James McCormick, an

assistant foreman of a local fire company, who was seen as a leader in the area. He was ridiculed

by the New York Times as the king of the offal-boilers and by the New-York Herald as Gen.

McCormick, of the pork gentry.87 McCormick threatened the police and inspectors, claiming

that he would shoot any man who laid a hand on his property. In the end, though, McCormick

removed his hogs and dismantled his pens and sheds before the police had their chance. Instead

of fighting the city for his right to keep the animals, it was reported that McCormick, like many

of his neighbors, planned to move his business to New Jersey.88 McCormick likely continued to

supply New Yorks cheap meat market with pork and ham, just with greater transportation costs.

By September, the Piggery War was mainly over. Delavan declared that they had removed

nine thousand hogs, demolished three thousand pens, and confiscated one hundred boilers. While

a good number of those hogs were driven to the pound, most were removed by their owners, such

as James McCormick, to New Jersey, Westchester, and Brooklyn. The transplantations only

increased problems in these areas where local governments struggled to control their own livestock populations. Hogs brought controversy wherever they roamed.89

By the middle of the nineteenth century, the Eighth Ward, where Henry Bourden and his

neighbors had fought tooth and nail to keep their hogs in 1825, was nearly devoid of these creatures. The only exceptions were the occasional herd ushered from the docks to slaughterhouses

or the clandestine hog stowed in someones apartment or basement.90 While a handful of piggeries would return to the upper reaches of the city under Mayor Fernando Woods sympathetic

administration, their stay was brief.91 For the most part, hogs were no longer a visible presence

in Manhattan. The anti-hogites had won.

Hogs had filled an important role in New York ecologically and economically. For a time they

kept garbage heaps somewhat under control by devouring what they could in areas often

neglected by sweepers. Following the Piggery War, city officials realized the enormous role pigs

had played in waste removal when they found themselves struggling to find a place to dump the

countless tons of offal that the hogs had once consumed.92 Hogs also helped to keep their owners

off the welfare rolls while they struggled with low wages and irregular work in the developing

market economy.

The hog controversies exposed a politically active city with growing class tensions. When

African American suffrage was limited in 1821 and many pro-hogites consequently lost their

ability to effectively petition the Common Council, they took to the streets and fought for their

right to use public space. New Yorkers, rich and poor alike, actively pressured the city to protect

their interests using whatever means they had available. Swine remained on the streets as long as

they did not just because the city government was incapable of enforcing its laws, but also

because they were at the center of a dynamic political debate between New Yorkers.

New Yorks filthy streets had cultivated an informal economy and a fertile environment for

roaming creatures, and during the first half of the nineteenth century, the municipal governments inability to effect long-lasting change made it possible for the New Yorkers and their

animals to continue using the streets as they had before. Despite the anti-hogites litany of arguments in petitions and newspapers, their ultimate success came because of factors beyond their

control. Cholera outbreaks and the panicked efforts to reform the city in order to prevent similar

crises eventually trumped the protests of pro-hogites and led to the hogs expulsion from the city.

Left in their wake was a city transformed with a new set of rules for using public space.

Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at PORTLAND STATE UNIV on January 8, 2015

652

Journal of Urban History 37(5)

The fights that raged over swine in nineteenth-century New York shaped the landscape of the

city. A hog-free New York was marked by parks and promenades, including the celebrated

Central Park that was cleared of the piggeries that once occupied its southern end. Olmsted and

the Central Park Board of Commissioners quickly passed a set of ordinances banning all livestock from entering the park and erected two pounds to hold errant animals, whether they were

hogs, cattle, goats, or geese.93 Central Park and other public spaces throughout the city were

intended for refinement, not for unapproved foraging and grazing. These places were better controlled but the battles over their use were far from over. New Yorkers would continue to push the

limits and shape the rules governing their public spaces. The controversies over hogs were part

of a much longer struggle.94

Nineteenth-century cities, such as New York, wrestled with how to manage public space during a time of rapid population growth. These were landscapes where the boundaries between

urban and rural blurred, and conflicts, such as those over hogs, helped to determine where these

lines would be drawn. Cities were and continue to be hybrid spaces, and what it means to be urban

is therefore constantly shifting. It is in these contentious moments when decisions are made to

incorporate or exclude that the city is ultimately defined.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author received financial support for the research of this article from the Howard R. Lamar Center for

the study of Frontiers and Borders, the Program in Agrarian Studies at Yale University, and the Beinecke

Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Notes

1. After the city began enforcing the hog law in the summer of 1821, they faced immediate resistance

when the catchers went to work. By the summer of 1822 most of the outer wards were exempt from

the hog law due to the actions of hog owners and the compromises made by their Aldermen. Hogs

in the Streets, New-York Evening Post, June 12, 1821; Extract from the Report, New-York Evening

Post, July 12, 1821; Minutes of the Common Council of the City of New York, 1784-1831 (New York:

Published by the City of New York, 1917), July 21, 1821, 11:722; Hogs Running at Large in the

Streets, New-York Evening Post, August 7, 1821; Police, New-York Spectator, August 7, 1821; Minutes of

the Common Council, June 10 1822, 12:430; Minutes of the Common Council, June 24, 1822, 12:447;

Minutes of the Common Council, July 8, 1822, 12:460-61.

2. Abner Curtis was appointed register and collector of dogs in 1811 and remained in that position for

seven years. During his first year on the job, Curtis witnessed the first dogcart riot in 1811. Another

dogcart riot occurred in 1818, following the end of his term. With the threat of rabies very real, dogs

were another urban animal considered a nuisance when running loose. Paul A. Gilje, The Road to

Mobocracy: Popular Disorder in New York City, 1763-1834 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina

Press, 1987), 224-27.

3. Quotes from Hog Law, New York Spectator, April 8, 1825. Regarding Henry Bourdens role in the

riot: Court of Sessions, Weekly Commercial Advertiser, April 19, 1825; People vs. Henry Bourden,

New York City Court of General Sessions Records, New York Municipal Archives, Roll 11. Henry Bourden

is likely the Henry Borden listed in the 1830 and 1840 U.S. censuses, living in the Eighth Ward. 1830

United States Federal Census, New York Ward 8, New York County, New York, Roll 97, 273; 1840

United States Federal Census, New York Ward 8, New York County, New York, Roll 302, 334.

Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at PORTLAND STATE UNIV on January 8, 2015

653

McNeur

4. Hog Law, New York Spectator; Minutes of the Common Council, March 14, 1825, 14:365; Minutes

of the Common Council, March 28, 1825, 14:410-11.

5. New Yorks hogs have been the subject of a handful of articles and chapters. In The Road to Mobocracy,

Paul Gilje places the hog riots of the 1820s and 1830s in the context of a string of popular riots in

the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and argues that the battles over hogs show a growing divide

between lower-class needs and middle-class sensibilities. Hendrik Hartog uses the prosecution of a hog

owner to show the ways municipal powers and legal arguments were transforming during this period in

both Public Property and Private Power and Pigs and Positivism. In A Delicate Balance Howard

Rock shows how artisans used hogs as part of a larger informal economy to make ends meet during

tough economic times. Finally, John Duffy repeatedly reminds readers how hogs were a constant presence in the antebellum city and a reminder to residents and historians of how inadequately New York

dealt with public health issues. This article builds on the work of these historians to reveal how these

political, economic, and public health struggles came together to shape public space and the urban

environment. Through this it is possible to understand more about how public space was used and ultimately controlled. Paul Gilje, Road to Mobocracy; Hendrik Hartog, Pigs and Positivism, Wisconsin

Law Review (July/August 1985): 899-934; Hendrik Hartog, Public Property and Private Power: The

Corporation of the City of New York in American Law, 1730-1870, Studies in Legal History (Chapel

Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1983), 139-42; Howard B. Rock, A Delicate Balance: The

Mechanics and the City, The New-York Historical Quarterly 63 (April 1979) 93-114; John Duffy, A

History of Public Health in New York City, 1625-1866 (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1968).

6. Anti-hogite and pro-hogite are terms that I have coined as shorthand for these two competing interests.

7. Lewis Mumford, The Culture of Cities (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1938), 252.

8. Urban environmental historians increasingly are challenging the idea that cities are exclusively social

artifacts. Authors such as Ari Kelman, Matthew Klingle, and Michael Rawson, among others, have

written about cities in ways that challenge the nature/culture dichotomy and invite readers to consider

the presence and influence of nature on cities as well as the reverse. Ari Kelman, A River and Its City:

The Nature of Landscape in New Orleans (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003); Matthew

Klingle, Emerald City: An Environmental History of Seattle (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007);

Michael Rawson, Eden on the Charles: The Making of Boston (Cambridge: Harvard University Press,

2010). See also Christine Meisner Rosen and Joel Arthur Tarr, The Importance of an Urban Perspective in Environmental History Journal of Urban History 20 (May 1994): 299-310.

9. For the Dutch, see I. N. Phelps Stokes, The Iconography of Manhattan Island, 1498-1909 (New York:

R. H. Dodd, 1915-1928), March 15, 1640, 4:92; June 27, 1650, 4:121; November 15, 1651, 4:124-25;

July 28, 1653, 4:140; November 15, 1651, 4:24-125; Duffy, A History of Public Health, 11-2. For the

English, see Minutes of the Common Council of the City of New York, 1675-1776 (New York: Dodd

Mead & Company, 1905), March 23, 1703, 2:258; July 20, 1708, 2:358; October 14, 1758, 6:152;

November 22, 1770, 7:244. Virginia Anderson looks at the havoc hogs and other livestock wreaked

in the British colonies of New England, though she does not dwell too much on urban animal issues.

Virginia DeJohn Anderson, Creatures of Empire: How Domestic Animals Transformed Early America

(New York: Oxford University Press, 2004).

10. Jane Allen, Population, in Kenneth T. Jackson, ed., The Encyclopedia of New York City (New Haven:

Yale University Press, 1995), 920-24; The People vs. Isaac Baptiste, New-York Daily Advertiser,

August 16, 1820; Charles H. Haswell, Reminiscences of an Octogenarian (1816-1860) (New York:

Harper & Brothers, 1896), 86.

11. Rock, A Delicate Balance, 134; Sean Wilentz, Chants Democratic: New York City and the Rise of the

American Working Class, 1788-1850 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1984); Seth Rockman looks

at a similar transition in early republican Baltimore. Seth Rockman, Scraping by: Wage Labor, Slavery,

and Survival in Early Baltimore (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press 2009).

Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at PORTLAND STATE UNIV on January 8, 2015

654

Journal of Urban History 37(5)

12. In Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790), Edmund Burke, a conservative Whig politician in

Britain, referred to the French masses as the swinish multitude when he warned readers of the perils

of allowing the lower classes to gain political power. Edmund Burke, Reflections on the Revolution in

France (New York, Penguin Classics, 1982). The phrase was consequently picked up by critics and

reappropriated by laborers and radical writers. Its notoriety made it a well-known phrase in antebellum

America and elsewhere. Surely the New York writers reveled in the way they were able to apply it to

their particular situation.

13. For more on the ways hogs have been used symbolically in politics and writing, see Carl Fisher,

Politics and Porcine Representation: Multitudinous Swine in the British Eighteenth Century, LIT 10

(2000): 303-26; Peter Stallybrass and Allon White, The Politics and Poetics of Transgression (Ithaca:

Cornell University Press, 1986), 45-59, 147-48; Brett Mizelle, I Have Brought My Pig to a Fine Market,

in Scott C. Martin, ed., Cultural Change and the Market Revolution in America, 1789-1860 (New York:

Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2005), 184; Robert Malcolmson and Stephanos Mastoris, The English Pig: A History (London: The Hambledon Press, 1998), 1-28.

14. Address of the Swine, New-York Evening Post, February 21, 1818.

15. Charles Henry Wilson, The Wanderer in America, or Truth at Home (Thirsk, England: Henry Masterman,

1824), 18-9. Many American cities, such as Philadelphia, Washington, DC, and Baltimore, as well as

many smaller cities, had roaming hog populations. One traveler, who referred to hogs as Americas

favorite pet, declared that he had not yet found any city, county or town where [he had] not seen

these lovable animals wandering about peacefully in huge herds. Ole Munch Raeder, Correspondent

from the Homeland, in Oscar Handlin, ed., This Was America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University

Press, 1949), 217. See also Lady Emmeline Stuart Wortley, Travels in the United States, Etc. During

1849 and 1850 (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1851), May 16, 1849, 13. Ironically, despite these travelers claims that hogs were a unique problem to New York or the United States, many Europeans cities

also struggled with their own roaming hogs, though to a lesser extent. Malcolmson and Mastoris, The

English Pig, 40-4.

16. New York City Common Council Papers, 1670-1831, City Inspector Petitions, Municipal Archives

Collections, Roll 65, 1818.

17. Horses make an interesting comparison to hogs, as they were equally, if not more, present on the streets

of the city, yet they rarely got the kind of negative attention that hogs received until much later in the

century when they were being replaced by automobiles. Not only were regal horses a status symbol for

wealthier New Yorkers, they were considered living machines, as Clay McShane and Joel Tarr have

termed them, and useful for rich and poor alike. They were much less divisive than hogs. Examples of

authors complaining about the disgrace brought on by hogs include: Hogs in the Streets, New-York

Evening Post, April 27, 1819; Swine, New-York Evening Post, November 3, 1819. On the role of

horses in the urban landscape: Clay McShane and Joel A. Tarr, The Horse in the City: Living Machines

in the Nineteenth Century (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007); Ann Norton Greene,

Horses at Work: Harnessing Power in Industrial America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press,

2008); Clay McShane, Gelded Age Boston, New England Quarterly 74 (August 2001): 274-302.

18. For more on the middle-class and wealthy American quest for refinement, see Richard Bushman, The

Refinement of America: Persons, Houses, Cities (New York: Vintage, 1993). There are many comparisons to be drawn between the way anti-hogites perceived lower-class New Yorkers as wrongly imposing

on public spaces and the way conservationists saw locals as desecrating the National Parks in the late

nineteenth and twentieth century. See Karl Jacoby, Crimes against Nature (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003); Louis S. Warren, Hunters Game (Cambridge, MA: Yale University Press, 1999);

Theodore Catton, Inhabited Wilderness (Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 1997);

and Mark David Spence, Dispossessing the Wilderness (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001).

19. See Elizabeth Blackmar, Manhattan for Rent, 1785-1850 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1989),

44-71; Wilentz, Chants Democratic.

Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at PORTLAND STATE UNIV on January 8, 2015

655

McNeur

20. Until 1821 the Common Council controlled the cost and weight of bread sold within the city limits with

a bread assize. Politically volatile, the debate over the bread assize lasted for over two decades and led

to bakers strikes and many disputes. The prices of other provisions not traditionally controlled by the

city continued to rise and fall, but mostly rise, making it difficult for many of New Yorks destitute to

purchase much at all. What E. P. Thompson and other historians have called the moral economy was

gradually disappearing and the poor had to devise new ways to deal with erratic pricing of basic needs.

New York (N.Y.) Common Council, Laws and Ordinances Ordained and Established by the Mayor,

Aldermen, and Commonalty of the City of New-York, in Common Council Convened (New York,

T & J. Swords, 1817), 51-6; Assize of Bread, New-York Herald, March 15, 1815; The Poor . . .

New-York Herald, March 18, 1815; Bread, New-York Evening Post, for the Country, March 5, 1822;

Rise of Milk, New-York Herald, November 30, 1816; Milk, New-York Herald, December 7, 1816;

Soup House in Frankfort-Street, near the Arsenal, New-York Herald, February 19, 1817; Society for

the Prevention of Pauperism in the City of New York, Plain Directions on Domestic Economy (New York:

Printed by Samuel Wood & Sons, 1821).

21. Raymond Mohl in Poverty in New York, 1783-1825 deems this first quarter of the nineteenth century

to be a transition period for American cities. The city was growing and its prosperity increasing, but

the municipal services were not developing at the same rate. The city corporation which served the

compact, stable community of the eighteenth century no longer met the needs of many thousands of

immigrant and native newcomers spread over a more expansive urban community. These services

expanded in a haphazard fashion, in response to emergencies and immediate pressures. Peter Gluck and

Richard Meister accentuate that the growth that occurred after the Revolution due to an increase in life

span, fertility, and immigration resulted in a certain level of instability that the government agencies

had to account for when developing institutions and defining their role. At the same time, this period

saw a growing division between what was urban and rural, physically, economically, and culturally.

Complementing these studies, Seth Rockman tracks the controversy over urban welfare systems and

the important yet insufficient role they played as a safety net for laborers in Baltimore during the early

Republic. See Mohl, Poverty in New York, 3-13; Peter R. Gluck and Richard J. Meister, Cities in Transition: Social Changes and Institutional Responses in Urban Development (New York: New Viewpoints,

1979), 3-9, 36-43; Rockman, Scraping by.

22. Remonstrances against Law to Prohibit Swine from Running at Large, New York City Common

Council Papers, Municipal Archives, Box 60V, Folder #497 Flat, May 19, 1817.

23. It is difficult to determine how New Yorkers were able to identify their own hogs based on available

records. Unlike in cities or towns where hogs were legal, there do not seem to be any ear mark registers

associating owners with specific symbols imprinted on their animals ear. The behavior of hogs going

home at night is recounted by Charles Dickens in the 1840s. Charles Dickens, American Notes for

General Circulation, in Park Benjamin, ed., The New World (New York: J. Winchester, 1842).

24. Remonstrances against Law to Prohibit Swine from Running at Large; The Petition of the Subscribers Inhabitants of the City of New York, New York City Common Council Papers, 1670-1831,

February 2, 1818, Roll 67.

25. To the Mayor and Corporation of the City of New-York, Republican Watch-Tower, June 13, 1809, 3.

26. For the Public Advertiser, Dirty Streets, No. 1, Public Advertiser, April 11, 1810, 2. For an overview

of urban American sanitation, see Martin V. Melosi, Garbage in the Cities: Refuse, Reform, and the

Environment, 1880-1980 (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1981), 13-20.

27. Minutes of the Common Council, May 18 ,1812, 7:146-47; see also, Minutes of the Common Council,

November 14, 1814, 8:84

28. See, for instance, Minutes of the Common Council, June 1, 1818, 9:668; Communication, New-York

Evening Post, June 29, 1819.

29. New York, May 15, 1799, Daily Advertiser, May 15, 1799; Correspondence between Peter Burtsell and

John Pintard, Inspector of Health, January 20, 1806. New York City Common Council Papers, 1670-1831,

Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at PORTLAND STATE UNIV on January 8, 2015

656

Journal of Urban History 37(5)

Roll 29; Minutes of the Common Council, May 28, 1810, 6:209; Public Health, New-York Evening Post,

August 12, 1825; Cholera Statistics, New York Mercury, August 15, 1832; City Intelligence, New York

Herald, May 18, 1849; Isaac Candler, A Summary View of America: Comprising a Description of the Face

of the Country, and of Several of the Principal Cities (London: T. Cadell, 1824), 22-4.

30. Quote of Ole Munch Raeder, a Norwegian lawyer who lived in New York in 1847. Ole Munch Raeder,

Correspondent from the Homeland, 217; Health of the City, New-York Daily Advertiser, October

29, 1819.

31. Griskin is the lean part of a hogs loin. The Swinish Multitude, New-York Evening Post, October 10, 1816.

32. For examples of boys riding hogs and getting into trouble, see The People v. Christian Harriet,

in D. Bacon, ed., The New-York Judicial Repository (New York: Gould and Banks, 1818), 262-63;

Swine, New-York Evening Post, March 17, 1818; More Serious Accidents from Hogs, New-York

Evening Post, October 29, 1818. For descriptions of victimized women and girls, see A Congratulation,

New-York Evening Post, December 31, 1817; The People v. Christian Harriet, in The New-York Judicial Repository, 262; Communication, New-York Evening Post, June 26, 1819; New-York May 28,

1810, The New-York Evening Post, May 29, 1810; To the Editor of the Evening Post, The New-York

Evening Post, June 28, 1819; Yesterday Afternoon, New-York Columbian, July 1, 1820.

33. Mr Stone, Northern Whig, August 1, 1815.

34. For more on women and household economy, see Jeanne Boydston, Home & Work: Housework, Wages,

and the Ideology of Labor in the Early Republic (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990); Rockman,

Scraping by, 158-93; Christine Stansell, City of Women: Sex and Class in New York, 1789-1860 (Urbana:

University of Illinois Press, 1987).

35. Allen, Population; Charles Lockwood, Manhattan Moves Uptown: An Illustrated History (Boston:

Houghton Mifflin Company, 1976), 50-71.

36. The Common Council had been debating the wording of a new law respecting free-roaming swine in

the months before Hammonds petition, but progress came to a standstill on October 21, 1816, when it

was laid on the table. Hammonds petition may have been an attempt to break the deadlock and get the

ordinance passed. Minutes of the Common Council, November 5, 1816, 8:670; May 17, 1817, 9:130. The

archivist at the Municipal Archives of New York was not able to locate the original petition. Rock makes

reference to the fact that the petition was signed by about two hundred names in A Delicate Balance.

37. The Swinish Multitude, Evening Post, May 26, 1817. This article traces the history of the proposed

hog laws from 1816 through May 1817, accounting for the possible reasons for its delay. The Common

Councils motives for tabling the ordinance are not mentioned in their minutes. Minutes of the Common

Council, May 17, 1817, 9:130.

38. Remonstrances against Law to Prohibit Swine from Running at Large.

39. The Swinish Multitude, New-York Evening Post, May 26, 1817.

40. Common Council, New-York Evening Post, May 21, 1817; Howard Rock and Paul Gilje, Sweep

O! Sweep O! African American Chimney Sweeps and Citizenship in the New Nation, William and

Mary Quarterly, 3rd Ser. 51 (July 1994): 507-38. For more on the free blacks of New York City, see

Shane White, Somewhat More Independent: The End of Slavery in New York City, 1770-1810 (Athens:

University of Georgia Press, 1991); and Leslie M. Harris, In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans

in New York City, 1626-1863 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003). Approximately half of the

petition signers were African American, based on New York State census records: Alice Eicholz and

James M. Rose, eds., Free Black Heads of Households in the New York State Federal Census, 1790-1830

(Detroit: Gale Research Co., 1981).

41. Harris, In the Shadow of Slavery, 116-18; Leonard P. Curry, The Free Black in Urban America, 1800-1850:

The Shadow of a Dream (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981), 88, 217-18.

42. Humor remained an important way for the anti-hogites to address what they saw as an embarrassment

to the city. It served as an entertaining and artful means for criticizing the city while also wooing potential anti-hogites. The Hogs and the Corporation, New-York Evening Post, May 27, 1817; The Hogs

and the Corporation, New-York Herald, May 28, 1817.

Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at PORTLAND STATE UNIV on January 8, 2015

657

McNeur

43. Minutes of the Common Council, June 23, 1817, 9:215-16; Gilje, The Road to Mobocracy, 225.

44. Quadroped Toleration, Intolerable, New-York Columbian, July 23, 1817; The Yankee in New-York,

Exile, July 26, 1817; Dogs and Hogs, Albany Argus, August 22, 1817; Communication,

New-York Evening Post, September 13, 1817; For the New-York Evening Post, New-York Evening

Post, September 3, 1817; Minutes of the Common Council, October 7, 1817, 9:310; Swine,

New-York Herald, October 11, 1817; A Congratulation, New-York Evening Post, December 31,

1817; A Law Respecting Swine, New-York Columbian, January 15, 1818, 9:3.

45. Minutes of the Common Council, December 15, 1817, 9:393.

46. Repeal of the Law Prohibiting Swine Running at Large, New-York Evening Post, December 29, 1817.

47. The Petition of the Subscribers Inhabitants of the City of New York, New York City Common Council

Papers, 1670-1831, February 2, 1818, Roll 67. The race of the signers was determined by checking them

against New York State census records: Eicholz and Rose, Free Black Heads of Households.

48. Minutes of the Common Council, February 2, 1818, 9:462.