Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Heo and Lee (2009) - IJHM PDF

Caricato da

Charlie RDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Heo and Lee (2009) - IJHM PDF

Caricato da

Charlie RCopyright:

Formati disponibili

International Journal of Hospitality Management 28 (2009) 446453

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

International Journal of Hospitality Management

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ijhosman

Application of revenue management practices to the theme park industry

Cindy Yoonjoung Heo a,*, Seoki Lee b

a

b

School of Tourism and Hospitality Management, Temple University, 1700 N. Broad Street, Suite 201, 215-204-5612, United States

School of Tourism and Hospitality Management, Temple University, 1700 N. Broad Street, Suite 201-F, 215-204-0543, United States

A R T I C L E I N F O

A B S T R A C T

Keywords:

Revenue management

Yield management

Theme park

Pricing

Revenue management (RM) has been an essential strategy to maximize revenue for many capacitylimited service industries. Considering the common industry characteristics of traditional RM industries,

the nature of the theme park industry suggests potential for enhancing revenue by exercising a variety of

RM techniques. This study suggests practices for theme park operators for successful RM application. In

addition, this study examines how customers perceive RM practice in the theme park industry compared

to a traditional RM industry, hotel industry. The ndings indicate that customers seem to perceive RM

practice in the theme park industry as relatively fair practices as similarly perceived for the hotel

industry. The ndings are encouraging for the theme park industry because a relatively similar level of its

customers perceived fairness of the RM practice compared to the hotel industry suggests that adoption

and implementation of the RM practice has great potential to become successful as it has been in

traditional RM industries, such as hotels.

2009 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Revenue management (RM), or yield management, is an

accepted, essential strategy to maximize revenue for many

capacity-limited service industries (Cross, 1997; Berman, 2005;

Chiang et al., 2007). RM is a demand-based pricing strategy to

control for optimal inventory levels and to forecast real-time

demand (Choi and Mattila, 2006). The airline industry successfully

invented, implemented and practiced RM after deregulation in

1978, and ever since, more service industries, such as hotels, rental

car agencies, and restaurants, began adopting the practices. Airline,

hotel, and rental car industries represent traditional RM applications because they share similar characteristics (e.g., perishable

service or product, xed capacity, distinct customer segmentation,

and price differentiation) (Chiang et al., 2007) and abundant

published research considers various RM issues for such industries

(Weatherford and Bodily, 1992; Kimes et al., 2002; Kimes and

Wirtz, 2003; Kimes, 2004, 2005; Kimes and Thompson, 2004;

Susskind et al., 2004; Berman, 2005).

Considering the common industry characteristics of traditional

RM industries, the nature of the theme park industry certainly

suggests potential for enhancing revenue by exercising a variety of

RM techniques. Similar to other industries already practicing RM,

the theme park industry also has perishable inventory, high xed

* Corresponding author. Tel.: +1 215 204 5612.

E-mail addresses: yheo@temple.edu (C.Y. Heo), seokilee@temple.edu (S. Lee).

0278-4319/$ see front matter 2009 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2009.02.001

and low variable costs, variable demands and segmentable

markets. However, RM strategies, for the theme park industry,

must be carefully developed, taking into additional consideration

unique characteristics. For instance, a theme parks capacity is

relatively more exible than that of hotel or airline industries. Also,

in general, visitors do not make reservations in advance for theme

park admission.

While the theme park industry has potential for applying RM

strategies, research on RM issues in theme park industry is scarce

and the current study attempts to ll that gap; therefore the purpose

of this study is to suggest RM strategies suited to the theme park

industry. To establish a basis for discussion, a delineation of the basic

attributes of the theme park industry and examination of current

pricing strategies are necessary rst steps. Then RM application for

the theme park industry will be developed by incorporating two

different types of characteristics: commonly shared characteristics

with traditional RM industries and unique characteristics of the

theme park industry. In addition, customers perceptions of RM in

the theme park industry will be examined and discussed compared

to a successful RM industry (i.e., hotel industry) because such

perceptions are as important as industrys characteristics for

successful implementation of RM (Chiang et al., 2007); If a customer

views RM practice as unfair, the increased revenues resulting from

RM may be temporary (Kimes, 2002). In summary, by proposing

potential applications of RM for the theme park industry and

empirically comparing customers perceived fairness on RM

between the theme park and hotel industry, this study will provide

theme park industry practitioners with practical insights and tools.

C.Y. Heo, S. Lee / International Journal of Hospitality Management 28 (2009) 446453

2. Literature review

2.1. Theme park industry

The literature on theme parks is limited and only few proposed

denitions of theme parks can be found. Pearce (1988) described a

theme park as extreme examples of capital intensive, highly

developed, user-oriented, man-modied, recreational environments. This study denes theme park as an aggregation of themed

attractions, including architecture, landscape, rides, shows, food

services, costumed personnel, and retail shops. Theme parks, in

general, apply themes to provide visitors with interesting

experiences different from daily life. The earliest theme parks in

the US began operation in the last half of the 19th Century (Graft,

1986). The rst American amusement park was the World

Columbian Exposition, held in Chicago in the 1893 (Weinstein,

1992). In 1897, Steeplechase Park, the rst of three signicant

amusement parks opened on Coney Island in Brooklyn, New York

(Weinstein, 1992). Disneyland, introduced in the mid-1950s in

Anaheim, California as a safe, clean, aesthetically appealing,

imaginative entertainment facility, had a design specically

catering to both children and adults (Milman, 1991). Theme parks,

especially regional parks, spread endemically across the US in the

late 1960s and 1970s. Since then, in the 1980s and into the 1990s,

most parks were developed to be destination parks (Economics

Research Associates, 1998a,b). However, the theme park industry

in the US is no longer experiencing high growth in terms of new

development. Because major theme park operators have few

signicant opportunities for new development in the US market,

they do not have new development plans in the US (Mitrasinovic,

2006).

The attendance at theme parks increased steadily during the

1980s (Braun and Soskin, 1998) and the growth continued,

averaging 35% throughout the 1990s, even during the 1990

1991 economic slump (Mintel Market Research Reports, 2006).

However during the recession of 2001, year-on-year growth rates

slowed to less than 1% and the theme park market growth was

below the 1990s average by 2002 (Mintel Market Research

Reports, 2006). But after a short struggle, caused by poor economic

conditions, US theme park attendance increased by 1.8% in 2004 to

reach 328 million (Mintel Market Research Reports, 2006).

Worldwide theme park attendance climbed by 2.2% in 2006,

showing stable to moderate growth. Total visits to the top 20 parks

in North America in 2006 increased 1.5% from the previous year;

this gure is a far slower growth pace than achieved in the past.

Although the theme park industry has enjoyed steady attendance

growth in the past several decades (Milman, 2001), the US theme

park market has entered a mature stage (Formica and Olsen, 1998;

Wong and Cheung, 1999). The attendance growth rate in the US

between 2000 and 2005 was the slowest compared to other

regions of the world, as Table 1 illustrates. The mature theme park

business became highly dependent on a higher proportion of

return visitors and faced new competition from other leisure and

447

tourism products, such as video games and online entertainment

(Braun and Soskin, 1998).

Several research areas, one of which is the cultural and social

aspects of theme parks, have been examined in the theme park

literature over the past two decades. Moscardo and Pearce (1986)

considered the potential role of historic theme parks in providing

domestic tourists with an authentic insight into their history and

culture. Supporting this notion is that Australians, traveling

domestically, perceive the historic theme park experience as an

essential aspect of the motive for visiting theme parks. Also

research showed that perceived authenticity is an important

element for satisfaction with the historic theme park experience

(Moscardo and Pearce, 1986). Mills (1990) analyzed the cultural

signicance of the growth of theme parks in the US and Europe.

Milman (1991) investigated residents attitudes toward and

participation patterns in local theme parks as a leisure activity

through data from central Florida residents.

In one of several research projects considering trends in and the

future of the theme park industry, Graft (1986) argued that the

entertainment business should keep itself fresh, exciting and

imaginative in order to avoid losing its appeal. Thus, the theme

park industry needs to continue to change by adapting to new

realities. Theme park operators have to remain mindful of the

futures impact which results from changes in demographics,

technology, governmental policy and social and economic conditions (Graft, 1986). Formica and Olsen (1998) suggested current

and future trends in the theme park industry and how to manage

the threats and opportunities caused by the environmental

changes of the 1990s.

Other studies also provided ndings from strategic and

marketing perspectives. Roest et al. (1997) investigated the role

of cost and benet in customers satisfaction and dissatisfaction

with theme park operation, and also tested differences in costs

and benets among theme parks and among visitor segments.

The results indicated that families with young children differed

from singles in desired search benet. Milman (1991) examined

marketing implications such as market identication and

segmentation, and McClung (1991) addressed multi-segmentation strategies. Ford and Milman (2001) demonstrated service

management concepts that have been applied by George C.

Tilyou, who opened Steeple Chase Park. Tilyou has been called

the father and king of the American amusement park, and his

management concept still guides operators of theme parks today

(Ford and Milman, 2000). Despite all this research, to date,

empirical research is lacking for pricing strategies for the theme

park industry.

Although the theme park industry has a long history of

extensive research, few investigations addressed RM concepts and

practices for this specic industry. Berman (2005) stated that

theme parks are one of the potential service industries for which

RM principles may be successfully applied, but specic development of an RM application for the theme park industry is yet to be

forthcoming.

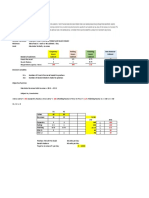

Table 1

Attendance at theme parks worldwide, by region, 20002005 (in millions).

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

Change 20002005

US

Asia-Pacic

Europe, the Middle East and Africa

Latin America

Canada

317

210

121

30.0

12.4

319

223

123

30.5

12.6

324

235

129

31.3

12.8

322

232

128

30.6

12.5

328

236

131

31.0

13.6

334

243

134

31.6

13.9

+5.4%

+15.7%

+10.7%

+5.3%

+12.1%

Total

690.4

708.1

732.1

725.1

739.6

756.5

+9.6%

Note: Figures are from PricewaterhouseCoopers Global Entertainment and Media Outlook: 20052009, US Census Bureau, International Database, Theme Park Tourism

International.

448

C.Y. Heo, S. Lee / International Journal of Hospitality Management 28 (2009) 446453

2.2. Revenue management

RM refers to selling perishable service products to the most

protable mix of customers to maximize revenue (Cross, 1997).

These strategic processes contain rational pricing for controlling

perishable assets across market segments to maximize revenues

(Cross, 1997; Baker and Murthy, 2002). As exemplied by

American Airlines, reporting an approximate 45% increase ($1.4

billion over 3 years) in revenue (Cook, 1998), and Hertz car rental,

reporting increased average revenue per rental by 5% (Carroll and

Grimes, 1995) from employing RM, research showed, in general,

RM increases a companys protability (Hanks et al., 1992; Smith

et al., 1992).

RM originated in the airline industry in the 1970s, and

subsequently has had wide application in travel and hospitality

industries such as hotel and rental car businesses. Extensive

research of the use of RM in various other industries have included

restaurants (Kimes et al., 1998, 2002; Kimes, 1999), casinos

(Hendler and Hendler, 2004), golf courses (Kimes, 2000; Kimes and

Schruben, 2002), resorts (Kasikci, 2006; Pinchuk, 2006), cruise

lines (Hosean, 2000), hospitals and health care providers (Lieberman, 2004).

RM traditionally involves segmenting customers, setting prices,

and controlling capacities to maximize the revenue generated from

a xed capacity (Kimes, 1989). Kimes (1989) identied a number of

preconditions for successfully using RM and factors for the

effective operation of RM in practice. In general, RM suits service

industries with xed capacity, variable demand and a segmentable

market (Kimes, 1989). In addition, advanced booking also needs to

be considered as another prerequisite for RM to be successful.

Reservation systems can help manage demand forecasting because

such systems can calculate inventory units in advance of

consumption. As Kimes (1989) stated, RM is basically a form of

price discrimination and market segmentation. Price discrimination helps a company to increase revenues in two ways: By

charging premium prices to the less price-sensitive market

segments, the company can gain greater revenue, and at the same

time charging discounted prices to a price-sensitive market

segment to encourage increased sales of the service that offset

the price reduction. For example, in the hotel industry, business

travelers are a recognizable, price-insensitive, market segment and

leisure travelers are known as the price-sensitive market segment.

Therefore, successful application of RM concepts requires distinct

market segments or particular market demands which appropriately lead to differential pricing.

However, customers perceptions of RM should be considered

along with industries characteristics for successful implementation of RM because customers perceptions and acceptance lead to

their behaviors that have a direct inuence on the performance of

RM (Chiang et al., 2007). Most companies set prices for their

products or services based on the cost of producing, selling, and

delivering them. However customers assign a certain value to

goods and services based on their own unique needs and desires,

not on cost for the products or services (Cross, 1997). A customers

perception of the value of the product depends mainly on

availability of alternatives, amount of disposable income, and

the urgency or need for the product or service (Zeithaml, 1988).

Only when the value perceived by customer matches or exceeds

the price, do customers execute a purchase (Cross, 1997). Core

principles of RM are based on customers perceived value for a

service or a product, not on cost. A product may be priced higher

than its cost if customers perceptions dictate the desired item or

service is worth the price.

Perceived fairness has been studied extensively as a measure of

price acceptability in marketing literature (Lichtenstein et al.,

1988; Campbell, 1999; Thaler, 1985; Maxwell, 2002). Perceived

fairness is found to be an important aspect for sustaining customer

satisfaction, loyalty, and long-term protability (Kimes and Wirtz,

2003). Campbells study (1999) showed that perceived unfairness

has a negative inuence on customers shopping behavior. The

knowledge of how a price has been determined has a signicant

effect on perceptions of pricing fairness, and consequently,

willingness to purchase (Maxwell, 2002). As Kimes (2002) pointed

out, RM practices have potential for the theme park industry as

long as customers view such practices as being fair. If customers

regard RM practice as representing unfair policies, RM practice

may lead to customers dissatisfaction, and therefore, the increased

revenues resulting from RM may not be long-term (Wirtz et al.,

2003).

The core of RM for the theme park industry is the concept of

demand-based pricing and optimal attendance level strategies.

This study discusses the applicability of RM prerequisites to the

theme park industry and examines customers perceptions of RM

in the theme park industry as compared to the hotel industry.

3. Application of revenue management to the theme park

industry

The theme park industry shares several common characteristics, such as relatively variable demand, perishable inventory and

cost structures with industries traditionally employing RM. And

thus, theme parks, generally, display the essential conditions for

applying RM effectively. However the theme park industry also has

unique characteristics distinguishing it from traditional RM

employing industries. For example, theme parks have relatively

exible capacity and advance-purchase reservations are not usual.

Therefore, successful application of the RM for the theme park

industry requires modications which consider both theme parks

similar characteristics with traditional RM industries and its

uniqueness. Table 2 presents a comparison of characteristics

between industries traditionally employing RM and the theme

park industry. Subsequent sections discuss these characteristics in

details.

3.1. Perishable inventory

Theme parks operating revenues originate primarily from sales

of admission tickets, with sales of food, beverages, and merchandise providing additional income. For example, Six Flags generated

approximately 54% of its revenue from sales of admission tickets in

2006 (Business Week, 2007) and 52.4% in 2007 (Six Flags 10-K,

2008). Other revenue sources such as food, beverage and

merchandise sales strongly related to admission ticket sales,

making this revenue source a determinant of total revenue.

Potential admission tickets sales for a specic day cannot be stored

for other days, and thus, unsold tickets have no value beyond a

particular day. Unsold tickets represent lost revenue; therefore

theme parks must strive to minimize unsold tickets and sell the

greatest number of admission tickets in a given time period to

maximize revenue. RM is one of the effective techniques to solve

this challenge. For example, the theme park industry can attract

price-sensitive customers and stimulate market growth by offering

discounts during the low attendance season, a typical RM practice.

RM practice also can help reduce unsold tickets, thereby

generating more revenue.

3.2. Cost structure

Developing a theme park requires substantial capital investment in terms of land and equipment (Formica and Olsen, 1998).

Furthermore, each year parks need signicant investment to add

new attractions to entice the required level of attendance,

C.Y. Heo, S. Lee / International Journal of Hospitality Management 28 (2009) 446453

449

Table 2

Comparison of characteristics between traditional RM industries and the theme park industry.

Characteristics

Ideal applications of RM

Theme park

Degree of

common feature

Perishable inventory

Cost structure

- Inventory is perishable

- Low cost of marginal sales in comparison

to marginal revenues

- High xed cost

- Variation in demand is signicant

- Demand is somewhat predictable

- Market is capable of being segmented

- Signicant differences in price elasticity

by market segment

- Capacity is xed

- Service providers have excess capacity at certain

times and excess demand at other times

- Inventory is perishable

- Low cost of marginal sales in comparison

to marginal revenues

- High xed cost

- Variation in demand is signicant

- Demand is somewhat predictable

- Market is cable of being segmented

- Differences in price elasticity by market segment

Similar

Demand

Segmentable market

Capacity limit

Reservations

made in advance

- Service is reserved by customers in different

time periods

- Uncertainty of actual usage despite reservations

creates possibility of unsold seats

especially repeat visitors (Dietvorst, 1995). Fixed costs do not vary

with the number of attendees, and will be incurred even during

slow seasons. On the other hand, the theme park industry

experiences a very low marginal cost increase for serving

additional customers. The theme park industry, characteristically,

encounters high xed costs and comparatively low variable costs.

Every attendee represents prot once the park reaches the

breakeven point and the costs per visitor in the slow seasons

are much higher than in the highly active seasons. This cost

structure explains why the theme park industry should adopt RM

practices to increase operational efciency because the low

marginal cost of sales allows for the exibility of discounting

during slow seasons, and price is the most exible element of

strategy in that pricing decisions can be made relatively promptly

and at low cost when compared to other elements of marketing

strategies (Avlonitis and Indounas, 2005).

3.3. Variable, but predictable demand

Seasonality is one of the unique, indeed a major problem, that

tourism industry has to face (Jang, 2004). Bar-On (1976)

investigated seasonality and suggested that the main causes of

seasonality are natural and institutional. Natural factors originate

from regular uctuations of the weather, and institutional factors

are related to several human activities like vacations. Nadal et al.

(2004) addressed two basic elements that cause seasonality in

tourism. The rst element relates to temporal variations in natural

phenomena, particularly those associated with climate and season

of the year. The second element, seasonal demand, depends on

social factors and policies concerning: specic customers, legislated holidays, school schedules, industrial and public holidays,

festivals, and other events that are usually based on historic

conventions (Nadal et al., 2004).

These two elements are also applicable to the theme park

market which is a part of tourism industry. Theme park operations

are highly seasonal like other hospitality and tourism industries.

For example, Six Flags normally generates more than 85% of its

revenues during the second and third quarters of a calendar year

(Business Week, 2007) with the most active period being between

Memorial Day in May and Labor Day in September (Six Flags 10-K,

2008). In addition, variation in demand is signicant by the season,

day of the week, and time of day (Ahmadi, 1997). For example,

most theme park visits occur on weekends rather then weekdays,

and visitors usually arrive early in the morning. The success of RM

relies on an accurate demand forecast. Although the demand for

theme park entertainment uctuates, customers demand for

- Capacity is relatively exible

- Theme parks have excess capacity during

low-demand seasons and excess demand at

high-demand seasons or on weekends

- Small percentage of or no reservations are

made in advance

Different

theme parks is predictable based on the previously identied basic

elements of seasonality. In addition theme park operators can use

attendance history observations to forecast demand accurately.

3.4. Segmentable market

The fundamental objective of RM strategies is to increase

revenue by adjusting prices to ll all available capacity (Berman,

2005). This price differentiating strategy is applicable to service

industries because of customer heterogeneity, which allows the

identical product to be sold to customers at a variety of prices

depending on their price elasticity (Tellis, 1986). Undoubtedly the

customer base includes those who are willing to pay a premium for

the convenience of the high-demand season, and others who prefer

to change the day of a visit to save some money.

The airline industry segments customers on each route into

various groups and sets a different price for each group. The

allocation of seats per class and the ticket price per class are the

keys to maximizing airlines yields. For example, segmenting

theme park customers can be according to demographics,

geography, ethnics or behavior: local residents are apt to visit a

park in the afternoon, and seniors are not constrained to theme

park visits during holidays. Additional divisions are also possible:

an individual whose profession requires shift- or weekend work

generally has free time during weekdays and is thus a potential

weekday theme park visitor. Theme park operators need to

discover each markets perceived value for a visit based on the

season of the year, the day of the week and the time of the day. The

key to this segmentation is the fact that customers are willing to

pay variable prices to visit during a specic time. The theme park

industry should distinguish between time-sensitive and pricesensitive types of customers, know the requirements of each, and

develop different pricing strategies to accommodate various types

of customers. Some theme parks use several RM practices such as

discount prices for children, groups and joint-entry tickets;

however application of discount promotions to attract a specic

segment has so far been mostly tactical.

3.5. Capacity limit

While industries traditionally using RM practices have xed

capacity, such as seats on an airplane and rooms in hotel, capacity

for theme parks is relatively exible. However, capacity control is a

critical issue for theme park operators. Excessive numbers of

attendees over an optimal capacity during the high-activity season

or the high-activity time of day cause problems. When a signicant

450

C.Y. Heo, S. Lee / International Journal of Hospitality Management 28 (2009) 446453

number of attendees arrive at the same time in the morning at the

entrance of the park, congestion is the result, and waiting

customers become frustrated. During the periods of greatest

activity, the more popular rides experience queues of waiting

customers, which can compound dissatisfaction. Guests in-park

per capita spending likely decreases if excessive numbers of

attendees clog the park. Overuse of facilities increases maintenance costs, and congestion raises safety issues and decreases

attendees satisfaction.

Theme park operators introduced special pass programs for

efcient queue management, expecting to reduce customers

dissatisfaction resulting from long-wait lines. For example, Disney

provides FastPass an advance-booking system, that allows a

limited number of customers reservations for one attraction at a

time, and Universal Studios offers Express Plus Pass that allows

customers to skip the regular lines at participating rides and

attractions. And several Six Flags Parks sell the Flash Pass to

customers who want to avoid standing in lines. The prices for those

services vary, depending on date, level of service, or number of

riders. Those programs cut waiting times for customers who

purchase special passes and facilitate customers ow in the theme

parks. However the theme park operators do not limit the number

of special tickets. If the total number of attendees exceeds the

optimal capacity, congestion and long-wait line are inevitable.

Therefore, theme park operators need to restrict the number of

attendees during the high-demand seasons to avoid customer

dissatisfaction. By charging premium prices to the time-sensitive

target market, price-sensitive customers may make a reservation

early or change their visitation schedule. Capacity limitation will

help theme park industry attain not only capacity utilization but

also added protability. Price-sensitive customers may be charged

a low price, while customers who are willing to pay a higher price

will be levied such a price (Avlonitis and Indounas, 2005). In

addition, with limited product inventory, capacity or limited

service, customers tend to perceive higher value for the scarce

commodity. Accordingly, attendees willingness to pay a price

premium increases. A theme park is able to increase revenue per

capita and total revenue, and reduce maintenance costs by

practicing RM strategies.

3.6. Advance-purchase reservations

Today, information technologies (IT) such as Internet and ecommerce have become crucial factors for business success for

industries traditionally practicing RM, and these IT trends will

continue for the predictable future (Chiang et al., 2007). RM

practicing industries use computerized reservation systems to

forecast demand and to calculate inventory; however, theme park

customers do not generally use reservation systems. Theme park

customers can buy admission tickets, online, in advance. But online

ticket purchases do not include choosing the date to visit.

Accordingly, pre-sold tickets do not help theme park operators

to forecast demand. Also, customers do not need to buy admission

tickets in advance for pricing purposes because the option of

advance-purchase tickets does not impact the ticket price at all

(i.e., there is no discount for an early purchase).

Theme park operators should initiate RM practices involving

reservation systems which allow forecasting demand accurately,

calculating available capacities, limiting the number of attendees

for specic times, and increasing operational efciencies. The

accuracy of forecasting has a direct impact on the performance of

RM (Chiang et al., 2007). Polt (1998) estimated that a 20% decrease

in forecasting error can increase the incremental revenue

generated from an RM system by 1%. An established reservation

system for a theme park would help more accurate prediction of

attendance. Theme park operators can control the availability of

discounts or premium admissions using statistical forecasting

techniques and mathematical optimization methods. In addition,

IT-based reservation systems can increase customers convenience

and satisfaction, when customers do not need to waste their

entertainment time by queuing at admission ticket windows.

Theme park managers also accrue benets from IT-based

reservations systems through improvement of operational efciency in terms of staff planning and facility maintenance.

Furthermore many traditional RM industries use sophisticated

pricing systems, called revenue management systems or yield

management system, which interact with reservation system and

employ techniques such as discounting early purchase, limiting

early sales at these discounted prices, and overbooking capacity

(Kimes, 1989; Lieberman, 1993). Complicated revenue management systems adjust prices according to the number of early

bookings and usually terminate reservations after exceeding the

available capacity (Desiraju and Shugan, 1999). Revenue management systems for the theme park industry provide analytical

insights that can drive revenue maximizing decisions for how

many admission tickets should be sold and at what price.

4. Customers perception of revenue management practice in

the theme park industry

RM has been extensively practiced in the traditional RM

industry, such as airline and hotel industry, and customers seem to

accept the application of RM in those industries (Kimes, 2002).

Therefore, this study compares customers perceived fairness of

RM practice in general as a demand-based pricing policy and four

particular RM practices in theme park industry with those of in

hotel industry. To collect data of the perceived fairness in the both

theme park and hotel industry, an online based survey method was

used. An invitation for participating in the survey was sent out

through email to students of a University in east coast of the U.S.

and 523 usable surveys were collected. The respondents were

asked to evaluate the fairness of demand-based pricing policy in

the hotel and theme park industry on a scale from 1 (extremely

unfair) to 7 (extremely fair), adopted from the perceived price

fairness scale used by Campbell (1999). In addition, they were

asked to evaluate how fair four pricing practices are on a 7-point

Likert scale; charging different price based on (1) timing of

reservation, (2) time of the day, (3) day of the week, and (4) season

of the year. Ahmadi (1997) mentioned that theme park attendance

levels uctuate signicantly according to the time of day, day of the

week, and season of the year. Therefore, theme parks can set

different pricing policies based on these uctuations in customers

demands. In addition, different pricing based on timing of

reservations is added to the survey, since this policy is a common

RM practice in traditional RM industries. Theme parks, as do hotels,

can charge lower prices for customers who make reservations well

in advance, and price increases as the target day comes closer.

Finally, demographic background variables (gender, age and

ethnicity) were measured.

Out of 523 respondents, male respondents were 25.4% (n = 133)

while 74.6% (n = 390) were females. Gender difference was not

found in all ve questions. The study next compares the two

industries in terms of customers perceived fairness of the ve RM

related questions, and Table 3 presents the results. In general, RM

practice as a demand-based pricing policy in both industries was

considered to be slightly fair. The mean for the hotel industry was

4.10 and for the theme park industry was 4.06 where the study

found no statistical difference between the two industries (tvalue = 0.39, p-value = 0.7). Respondents rated the fairness of the

variable pricing practice based on timing of reservation as 4.28 for

the hotel industry, and 4.01 for the theme park industry. The

difference between the two industries was statistically signicant

C.Y. Heo, S. Lee / International Journal of Hospitality Management 28 (2009) 446453

Table 3

Comparison of perceived fairness of RM practice in the hotel and theme park

industry.

Demand-based

pricing policy

Industry

Mean

t-statisticy

Hotel

515

4.10

0.39

0.70

2.53

0.01

p-value

Theme park

514

4.06

Hotel

511

4.28

Theme park

509

4.01

Season of the year

Hotel

Theme park

517

515

4.12

4.57

4.00

<0.01

Day of the week

Hotel

Theme park

509

507

4.04

4.22

1.62

0.11

Timing of

reservation

t-test assumes equal variances for the two samples.

(p-value = 0.01). This nding is not surprising because the theme

park industry does not extensively utilize the reservation system

whereas the opposite is true for the hotel industry. Variable pricing

practice based on season of the year was rated more fair in the

theme park industry (mean value = 4.57) than hotel industry

(mean value = 4.12); the difference was statistically signicant (pvalue = 0.00). For the variable pricing practice based on day of the

week, the perceived fairness was higher in the theme park

industry, but the difference between the hotel and theme park

industry was not statistically signicant (t-value = 1.62; pvalue = 0.11). While the pricing practice based on the time of

day is applicable to the theme parks, the practice seems not

realistic for the hotel industry. Therefore, t-test was not performed

to compare the two industries for this practice. For the theme park

industry, the practice based on time of the day is found to be

perceived as fair as the other pricing policies (mean value = 4.06).

The ndings indicate that customers seem to perceive RM

practice of the theme park industry as relatively fair practices as of

the hotel industry. The ndings are encouraging for the theme park

industry because a relatively similar level of its customers

perceived fairness of the RM practice compared to the hotel

industry suggests that its adoption and implementation of the RM

practice has great potential to become successful as it has been in

the traditional RM industry such as the hotel industry.

5. Implications

5.1. Implications from the empirical analysis

This study has presented two main themes: (1) proposing

applications of RM to the theme park industry, and (2) conducting

an empirical analysis comparing customers perceived fairness of

RM between the theme park and the hotel industry. Although the

study did not empirically examine all of the proposed applications

of RM to the theme park, investigating customers perceived

fairness on RM practices reinforces potential of a successful

implementation of RM practice in the theme park industry.

451

Customers perceived fairness of general RM concept in the hotel

and theme park industry appears to be similar to each other.

Surprisingly, customers perceived that RM practices based on

season of the year and time of the day are even fairer in the theme

park industry than in the hotel industry, although most US theme

parks, including Disneyland and Six Flags, adopt at-rate admission all around the year. Thus, the theme park industry may

consider implementing RM practices based on season of the year

and even day of the week as basic rate fences.

Along with the variable admission pricing policy, this study

proposes that the theme park industry should apply dynamic

pricing strategies in which operators charge different prices based

on the timing of a purchase, just as airlines or hotels currently

practice. However, survey ndings suggest that customers

perceive RM based on timing of reservation in theme park is not

as fair as in the hotel industry. Based on the nding, theme park

operators should nd a way to change customers perception about

the timing of reservation. However, once theme parks start

implementing an advance-purchase reservation system as proposed by this study and as more customers become familiar with

the practice, the perception will likely change accordingly.

5.2. Implications from the proposed applications of RM

Table 4 summarizes suggested practices for theme park

operators for successful RM application. Strategically applied,

RM should comprise considerations of not only increased revenue

for the company but also greater satisfaction for the customer

(Kimes and Wirtz, 2003) because customers satisfaction is

ultimately the key to long-term success (Roest et al., 1997).

Customer dissatisfaction rates have a signicant relationship to

long waiting times and congestion; thus maintaining the optimum

level of attendance in a park becomes a critical task for the theme

parks operator. To accomplish this goal, the suggestion is that

theme park operators limit the number of attendees during the

popular seasons. This practice will enable theme park operators to

increase operational efciency with shorter waiting times and less

congestion. Also, the practice will help the operators not overuse

facilities and rides, and therefore, reduce maintenance costs along

with possibly extending intervals between renovations. Consequently, the overall level of customer satisfaction will improve.

Some parks in Asia currently practice an attendee limitation policy.

For example, Caribbean Bay of Samsung Everland, a water park in

South Korea, limits the number of attendees during the highdemand season to maintain attendees quality of experience and

safety. Since theme park attendees are aware of the attendee

limitation policy, they make reservations for attending Caribbean

Bay just as they would for concert tickets. This attendee limitation

strategy helps Caribbean Bay to position itself as a premium park in

South Korea. Tokyo Disney is another theme park that limits the

admission occasionally during high-demand periods.

The second point of signicance is that theme parks should

create variable admission price policies based on customers

demand. In general, theme parks in US charge a at-rate admission

Table 4

Suggested practice for successful RM application in the theme park industry.

Current practice

Suggested practice

Capacity control

- Queue management in parks

- No capacity limit

- Control demand with variable price

- Limit number of attendees during high-demand seasons and/or times

Pricing policy

- Flat admission rate all though the year

- Discount for specic target

- Seasonal pricing promotion

- Time-based pricing policy (pre-xed)

- Demand-based dynamic pricing strategy (variable)

Reservation system

- Presale of admission tickets through online resources

- Operate online reservation system connected with revenue management system

452

C.Y. Heo, S. Lee / International Journal of Hospitality Management 28 (2009) 446453

all through the year. They have several discount policies for specic

targets, such as children, seniors, groups, and local residents and

have annual pass programs that allow members to revisit the

theme park at no additional charge for one year. If theme parks

operators have more than two parks, they also can initiate joint

park admission tickets and package programs combined with

accommodations. Theme parks can apply discounts for multiple

day tickets, such as Disneys Magic Your Way, to encourage

customers to stay longer. Furthermore, during slow seasons theme

park operators often issue discount coupons to temporarily attract

customers. However, those policies do not fully consider the

possibility of more varied price ranges to accommodate a wider

variety of customers demand levels, such as premium pricing

during high-demand seasons. By setting different pricing for each

season of the year, day of the week, and time of day (i.e.,

implementing variable admission price policies based on customers demands), theme park operators can charge appropriate

prices reecting demand differentials that maximize revenue.

Because customers do not generally make a reservation for the

theme park, they are not familiar with the RM practice in theme

park. Therefore practitioners in the theme park need to make an

effort to get customers familiar with reservation for the theme

park. By implementing the dynamic pricing strategy, the operators

can optimize capacity availability by offering appropriate discounts at the right times to stimulate demand without losing

revenues. In addition, the strategy may alleviate customers

dissatisfaction levels. Some customers may think the variable

pricing policy of the theme park is not fair which may create a

negative perception of RM; however, customers would be more

accepting of RM practices, if they perceive a certain controls over

pricing. For instance, a customer may be able to purchase a ticket

for a lower price than the price level pre-set by the theme park

operators if the customer purchases the ticket a half year ahead of

the visit. The admission ticket price will rise to full-price as the visit

date approaches. Before adopting dynamic pricing policies, theme

park operators need to determine the precise conditions for early

purchase discount and have sophisticated pricing models that

suggest appropriate prices depending on available capacity.

Therefore, to make dynamic pricing strategy work properly, ITbased reservation systems and revenue management systems are

essential. IT-based reservation systems will provide theme park

operators with information of customer demand and enable the

operators to set the best price, for a given demand level, at an

appropriate time interval between the purchase and actual visit.

Mielke et al. (1998) suggested that theme park managers

should control in-park revenue, operating cost and customer waittime as performance measures for efcient operation. Customer

wait-time is particularly important because it is a measure of the

perceived quality of service experienced by customers. RM may

help optimize all three performance measures: Properly allocating

customer demand can reduce the labor cost and customer waittime, while time-based pricing policies and demand-based

dynamic pricing strategies will increase total revenue.

6. Future research

This paper presents RM application for the theme park industry

based on the industrys characteristics and examination of its

customers perceived fairness of RM practices. Studies of customers perceived value for a theme park experience during different

seasons or times should be examined as a next step. The ndings

will help theme park operators to create time-based pricing

policies. For the future research, customers perceived value of

experience should be investigated to build a proper rate fence that

determines who pays which price. Besides timing of visitation, rate

fences for the theme park industry might include customer

characteristics (e.g., frequent customers receive a discount) and

transaction characteristics (e.g., customers who book the ticket

early receive a discount). Since theme park customers can be

segmented in various ways, research into price elasticity of

different market segments is also suggested. Last, a comparison of

different segments of the hospitality and tourism industry (e.g.,

restaurant, theme park, golf-club, gallery and museum) in terms of

customers perceived fairness of the RM practice may be

encouraged to provide a more comprehensive picture of the RM

practice in the hospitality and tourism industry as a whole.

References

Ahmadi, R.H., 1997. Managing capacity and ow at theme parks. Operations

Research 45 (1), 113.

Avlonitis, G.J., Indounas, K.A., 2005. Pricing of services: an empirical analysis from

the Greek service sectors. Journal of Marketing Management 21 (3), 339362.

Baker, T., Murthy, N.N., 2002. A framework for estimating benets of using auctions

in revenue management. Decision Sciences 33 (3), 385413.

Bar-On, R., 1976. Seasonality in Tourism. Economics Intelligence Unit, London.

Berman, B., 2005. Applying yield management pricing to your service business.

Business Horizons 48 (2), 169179.

Braun, B.M., Soskin, M.D., 1998. Theme park competitive strategies. Annals of

Tourism Research 26 (2), 438442.

Campbell, M.C., 1999. Perceptions of price unfairness; antecedents and consequences. Journal of Marketing Research 36 (2), 187199.

Carroll, W.J., Grimes, R.C., 1995. Evolutionary change in product management:

experiences in the car rental industry. Interfaces 25 (5), 84104.

Chiang, W., Chen, J., Xu, X., 2007. An overview of research on revenue management:

current issues and future research. International Journal of Revenue Management 1 (1), 97128.

Choi, S., Mattila, A., 2006. Impact of information on customer fairness perceptions of

hotel revenue management. Cornell Hotel & Restaurant Administration Quarterly 47 (1), 2735.

Cook, T.M., 1998. SABRE soars. ORMS Today 25 (3), 2631.

Cross, R.G., 1997. Revenue Management: Hard-Core Tactics for Market Domination.

Broadway Books, New York.

Desiraju, R., Shugan, S.M., 1999. Strategic service pricing and yield management.

Journal of Marketing 63 (1), 4456.

Dietvorst, A., 1995. Tourist Behavior and the Importance of Time-Space Analysis,

Tourism and Spatial Transformations: Implications for Policy and Planning. CAB

International, Wallingford.

Economics Research Associates, 1998a. Theme park development case study

Fiesta Texas. Retrieved on June 10, 2008, from http://www.hotel-online.com/

Trends/ERA/ERAStudy/Fiesta.html.

Economics Research Associates, 1998b. The future of theme parks in international

tourism. Retrieved on June 10, 2008, from http://www.hotel-online.com/

Trends/ERA/ERARoleThemeParks.html.

Ford, R.C., Milman, A., 2000. George C. Tilyou: developer of the contemporary

amusement park. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 41

(4), 6271.

Formica, S., Olsen, M.D., 1998. Trends in the amusement park industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 10 (7), 297308.

Graft, J.H., 1986. The future of amusement parks and attraction industry. Tourism

Management 7 (1), 6062.

Hanks, R.B., Noland, R.P., Cross, R.G., 1992. Discounting in the hotel industry: a new

approach. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 33 (3), 4045.

Hendler, R., Hendler, F., 2004. Revenue management in fabulous Las Vegas; combining customer relationship management and revenue management to maximize protability. Journal of Revenue & Pricing Management 3 (1), 7379.

Hosean, J., 2000. Capacity Management in the Cruise Industry Yield Management:

Strategies for the Service Industries. Thomson, London.

Jang, S., 2004. Mitigating tourism seasonality. A quantitative approach. Annals of

Tourism Research 31 (4), 819836.

Kasikci, A.V., 2006. Palapa politics: simplifying operations for guest satisfaction.

Cornell Hotel & Restaurant Administration Quarterly 47 (1), 8183.

Kimes, S.E., 1989. The basics of yield management. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant

Administration Quarterly 30 (3), 1419.

Kimes, S.E., 1999. Implementing restaurant revenue management: a ve-step

approach. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 34 (3), 1621.

Kimes, S.E., 2000. Revenue management on the links: applying yield management

to the golf-course industry. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration

Quarterly 41 (1), 120127.

Kimes, S.E., 2002. Perceived fairness of yield management. Cornell Hotel and

Restaurant Administration Quarterly 43 (1), 2130.

Kimes, S.E., Schruben, L.W., 2002. Golf course revenue management: a study of tee

time intervals. Journal of Revenue and Pricing Management 1 (2), 111120.

Kimes, S.E., 2004. Restaurant revenue management: implementation at Chevys

Arrowhead. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 45 (1),

5267.

Kimes, S.E., 2005. Restaurant revenue management: could it work? Journal of

Revenue & Pricing Management 4 (1), 9597.

C.Y. Heo, S. Lee / International Journal of Hospitality Management 28 (2009) 446453

Kimes, S.E., Chase, B., Choi, S., Lee, P., Ngonzi, E., 1998. Restaurant revenue management: applying yield management to the restaurant industry. Cornell Hotel and

Restaurant Administration Quarterly 39 (3), 3239.

Kimes, S.E., Thompson, G.M., 2004. Restaurant revenue management at Chevys:

determining the best table mix. Decision Sciences 35 (3), 371392.

Kimes, S.E., Wirtz, J., 2003. Has revenue management become acceptable? Journal

of Service Research 6 (2), 125135.

Kimes, S.E., Wirtz, J., Noone, B.M., 2002. How long should dinner take? Measuring

expected meal duration for restaurant revenue management. Journal of Revenue & Pricing Management 1 (3), 220233.

Kolb, E., 2007. Time to give six ags a ride. Business Week. Retrieved July 17, 2008

from

http://www.businessweek.com/investor/content/jul2007/pi20070716

_350690.htm.

Lieberman, W.H., 1993. Debunking the myths of yield management. Cornell Hotel &

Restaurant Administration Quarterly 34 (1), 3444.

Lieberman, W.H., 2004. Revenue Management in the Health Care Industry, Revenue

Management and Pricing; Case Studies and Applications. Thomson, London.

Lichtenstein, D.M., Bloch, P.H., Black, W., 1988. Correlates of price acceptability.

Journal of Consumer Research 15 (2), 243252.

Maxwell, S., 2002. Rule-based price fairness and its effect on wiliness to purchase.

Journal of Economic Psychology 23 (2), 191212.

McClung, G.W., 1991. Theme park selection: factors inuencing attendance. Tourism Management 12 (2), 132140.

Mielke, R., Zahralddin, A., Padam, D., Mastaglio, T., 1998. Simulation applied to

theme park management. Paper presented at the Winter Simulation Conference.

Milman, A., 1991. The role of theme park as a leisure activity for local comminutes.

Journal of Travel Research 29 (3), 1116.

Milman, A., 2001. The future of the theme park and attraction industry: a management perspective. Journal of Travel Research 40 (2), 139147.

Mills, S.F., 1990. Disney and the promotions of synthetic worlds. American Studies

International 28 (2), 6680.

Mitrasinovic, M., 2006. Total Landscape, Theme Parks, Public Space. Ashgate Publishing, London.

Mintel Market Research Reports, 2006. Theme park tourism International July

2006. Retrieved on July 19, 2008, from http://libproxy.temple.edu:2219/sinatra/oxygen_academic/search_results/show&/display/id=187841.

453

Moscardo, G., Pearce, P., 1986. Historic theme parks: an Australian experience in

authenticity. Annals of Tourism Research 13 (3), 467479.

Nadal, J.R., Font, A.R., Rosselo, A.S., 2004. The economic determinants of seasonal

patterns. Annals of Tourism Research 31 (3), 697711.

Pinchuk, S.G., 2006. Applying revenue management to palapas: optimize prot and

be fair and consistent. Cornell Hotel & Restaurant Administration Quarterly 47

(1), 8491.

Pearce, P.L., 1988. The Ulysses Factor: Evaluating Visitors in Tourist Settings.

Springer-Verlag, New York.

Polt, S., 1998. Forecasting is difcult especially if it refers to the future. Paper

presented at the Reservations and Yield Management Study Group Annual

Meeting Proceedings, Melbourne, Australia, AGIFORS.

Roest, H., Pieters, R., Koelemeijer, K., 1997. Satisfaction with amusement parks.

Annals of Tourism Research 24 (4), 10011005.

Smith, B.A., Leimkuhler, J.F., Darrow, R.M., 1992. Yield management at American

airlines. Interfaces 22 (1), 831.

Six Flags, Inc., 2008. Form 10-K. Retrieved October 27, 2008 from http://library.corporate-ir.net/library/61/616/61629/items/303231/SIX_2007_10K.pdf.

Susskind, A.M., Reynolds, D., Tsuchiya, E., 2004. An evaluation of guests preferred

incentives to shift time-variable demand in restaurants. Cornell Hotel and

Restaurant Administration Quarterly 45 (1), 6884.

Thaler, R., 1985. Mental accounting and consumer choice. Marketing Science 4 (3),

199214.

Tellis, G., 1986. Beyond the many faces of price: an integration of pricing strategies.

Journal of Marketing 50 (4), 146160.

Weatherford, L., Bodily, S., 1992. A taxonomy and research overview of perishableasset revenue management: yield management, overbooking and pricing.

Operations Research 40 (5), 831844.

Weinstein, R.M., 1992. Disneyland and Coney Island: reections on the evolution of

the modern amusement park. Journal of Popular Culture 26 (1), 131164.

Wirtz, J., Kimes, S.E., Jeannette, H.P.T., Patterson, P., 2003. Revenue management:

resolving potential customer conicts. Journal of Revenue & Pricing Management 2 (3), 216226.

Wong, K.K.F., Cheung, P.W.Y., 1999. Strategic theming in theme park marketing.

Journal of Vacation Marketing 5 (4), 319332.

Zeithaml, V.A., 1988. Consumer perceptions of price, quality and value: a meansend model and synthesis of evidence. Journal of Marketing 52 (3), 222.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Demanf Pricing in The US Theme ParkDocumento23 pagineDemanf Pricing in The US Theme Parkkartika tamara maharaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 10 PDFDocumento3 pagineChapter 10 PDFGajanan Shirke AuthorNessuna valutazione finora

- Industry Opportunity AnalysisDocumento12 pagineIndustry Opportunity AnalysisEdbelyn AlbaNessuna valutazione finora

- Examining The Impact of Visitors' Emotions and Perceived Quality Towards SatisfactionDocumento15 pagineExamining The Impact of Visitors' Emotions and Perceived Quality Towards Satisfactionparklong16Nessuna valutazione finora

- Annals of Tourism Research: Florian J. Zach, Martin Schnitzer, Martin FalkDocumento15 pagineAnnals of Tourism Research: Florian J. Zach, Martin Schnitzer, Martin FalkLuz Mary MendozaNessuna valutazione finora

- Lt6p09es Rmp Cw1Documento9 pagineLt6p09es Rmp Cw1yt.psunNessuna valutazione finora

- Jurnal AkomodasiDocumento15 pagineJurnal AkomodasiGian Soleh HudinNessuna valutazione finora

- Full TextDocumento50 pagineFull TextJane BocayaNessuna valutazione finora

- Taking Stock of Place of Origin Branding: Towards Reconciling The Requirements and Purposes of Destination Marketing and Export MarketingDocumento11 pagineTaking Stock of Place of Origin Branding: Towards Reconciling The Requirements and Purposes of Destination Marketing and Export MarketingfadligmailNessuna valutazione finora

- Journal of Convention & Event ToruismDocumento26 pagineJournal of Convention & Event ToruismHan JongJinNessuna valutazione finora

- Global Theme Park Market: Trends & Opportunities (2014-19) - New Report by Daedal ResearchDocumento10 pagineGlobal Theme Park Market: Trends & Opportunities (2014-19) - New Report by Daedal ResearchDaedal ResearchNessuna valutazione finora

- Pike & Mason - Destination Competitiveness Through The Lens of Brand Positioning - The Case of Australia's Sunshine CoastDocumento26 paginePike & Mason - Destination Competitiveness Through The Lens of Brand Positioning - The Case of Australia's Sunshine CoastGerson Godoy RiquelmeNessuna valutazione finora

- Theme Park Development Costs - Initial Investment Cost Per First YDocumento13 pagineTheme Park Development Costs - Initial Investment Cost Per First YRenold DarmasyahNessuna valutazione finora

- KrshowDocumento15 pagineKrshowIhsan MuhtadiNessuna valutazione finora

- Market Research and Target Market Segmentation inDocumento14 pagineMarket Research and Target Market Segmentation inAsh LayNessuna valutazione finora

- Destination Marketing Organizations and Destination Marketing - A Narrative Analysis of The LiteratureDocumento26 pagineDestination Marketing Organizations and Destination Marketing - A Narrative Analysis of The LiteratureFlorentin Drăgan100% (1)

- The Economic Impact of Theme Parks On RegionsDocumento126 pagineThe Economic Impact of Theme Parks On RegionsElena LlanesNessuna valutazione finora

- Module Code: Module Title:: Carry Equal MarksDocumento4 pagineModule Code: Module Title:: Carry Equal MarksHardeep PathakNessuna valutazione finora

- Research Methods & ProjectsDocumento9 pagineResearch Methods & Projectsyt.psunNessuna valutazione finora

- Destination Marketing Research: A Narrative ReviewDocumento4 pagineDestination Marketing Research: A Narrative ReviewTarek SouheilNessuna valutazione finora

- Determining Factors of Theme Park AttendanceDocumento58 pagineDetermining Factors of Theme Park Attendanceloong1Nessuna valutazione finora

- A Review On Value Creation in Tourism IndustryDocumento10 pagineA Review On Value Creation in Tourism IndustryPablo AlarcónNessuna valutazione finora

- Pest Analysis Five Forces AnalysisDocumento7 paginePest Analysis Five Forces AnalysisFakhrul IslamNessuna valutazione finora

- Marketing EnvironmentDocumento9 pagineMarketing EnvironmentRakshit PandeyNessuna valutazione finora

- Pike, Bianchi, Kerr & Patti - Consumers-Based Brand Equity For Australia As A Long Haul Tourism Destination in An Emerging MarketDocumento27 paginePike, Bianchi, Kerr & Patti - Consumers-Based Brand Equity For Australia As A Long Haul Tourism Destination in An Emerging MarketGerson Godoy RiquelmeNessuna valutazione finora

- OF (Business Environment) : Submitted To-Submitted byDocumento21 pagineOF (Business Environment) : Submitted To-Submitted byabhinavsangraiNessuna valutazione finora

- Assessment of Tourist CompetitivenessDocumento23 pagineAssessment of Tourist CompetitivenessPoshan RegmiNessuna valutazione finora

- Measuring The Operational Efficiency of IndividualDocumento9 pagineMeasuring The Operational Efficiency of IndividualRaj ThadaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Exploring tourism clustering as a development strategy for rural communitiesDocumento4 pagineExploring tourism clustering as a development strategy for rural communitiesTarek SouheilNessuna valutazione finora

- Destination Marketing PDFDocumento87 pagineDestination Marketing PDFRoxana Irimia100% (2)

- Industrial Entropy in Tourism SystemsDocumento6 pagineIndustrial Entropy in Tourism SystemsCamila De Almeida TeixeiraNessuna valutazione finora

- Airport Advertising EffectivenessDocumento15 pagineAirport Advertising EffectivenessShahriar AziziNessuna valutazione finora

- 1-s2.0-S0261517711001816-mainDocumento14 pagine1-s2.0-S0261517711001816-mainThiagoNessuna valutazione finora

- A Multidimensional Scale Measuring Theme Park PerformanceDocumento17 pagineA Multidimensional Scale Measuring Theme Park PerformanceiraniansmallbusinessNessuna valutazione finora

- Tourism Dissertation Topic ExamplesDocumento4 pagineTourism Dissertation Topic ExamplesWhoCanWriteMyPaperAtlanta100% (1)

- Relationship Between ICT and InternationDocumento18 pagineRelationship Between ICT and Internationziabhatti958Nessuna valutazione finora

- Aguas Veiga ReisDocumento12 pagineAguas Veiga ReisoleduaNessuna valutazione finora

- A Stakeholder Perspective On Policy Indicators of Destination CompetitivenessDocumento7 pagineA Stakeholder Perspective On Policy Indicators of Destination CompetitivenessGrace Kelly Avila PeñaNessuna valutazione finora

- Part One ResearchDocumento3 paginePart One ResearchNicole GarciaNessuna valutazione finora

- Kozak 1999Documento11 pagineKozak 1999fadli adninNessuna valutazione finora

- Tourism Marketing: A Game Theory Tool For Application in Arts FestivalsDocumento15 pagineTourism Marketing: A Game Theory Tool For Application in Arts FestivalsCristina LupuNessuna valutazione finora

- Tourism Egypt ArticleDocumento8 pagineTourism Egypt ArticleshinkoicagmailcomNessuna valutazione finora

- Review of Literature and Research Methodology: NtroductionDocumento18 pagineReview of Literature and Research Methodology: NtroductionEkta Tractor Agency KhetasaraiNessuna valutazione finora

- International Services Marketing: Review of Research, 1980-1998Documento14 pagineInternational Services Marketing: Review of Research, 1980-1998cpuneethoneyNessuna valutazione finora

- Joint Venturesversuswholly Owned Subsidiaries: Svensson (1996) and Meyer (1997)Documento2 pagineJoint Venturesversuswholly Owned Subsidiaries: Svensson (1996) and Meyer (1997)翁玉洁Nessuna valutazione finora

- Impact of Monitary Policy in Tourism IndustryDocumento47 pagineImpact of Monitary Policy in Tourism IndustryGURUKRIPA COMMUNICATIONNessuna valutazione finora

- A Comparison of Service Quality Attributes For Stand-Alone and Resort-Based Luxury Hotels in Macau PDFDocumento21 pagineA Comparison of Service Quality Attributes For Stand-Alone and Resort-Based Luxury Hotels in Macau PDFfirebirdshockwaveNessuna valutazione finora

- Progress and Development of Information and Communication Technologies in HospitalityDocumento19 pagineProgress and Development of Information and Communication Technologies in HospitalityDiana KudosNessuna valutazione finora

- Tenant Mix Variety in Regional Shopping Centres: Some UK Empirical AnalysesDocumento29 pagineTenant Mix Variety in Regional Shopping Centres: Some UK Empirical AnalysesnoorsidiNessuna valutazione finora

- Dou 2020Documento13 pagineDou 2020Dini PutriNessuna valutazione finora

- Tourism Management: Zheng Xiang, Bing PanDocumento10 pagineTourism Management: Zheng Xiang, Bing PanMersed BarakovicNessuna valutazione finora

- Thesis Guide ComplexDocumento5 pagineThesis Guide Complexzoey zaraNessuna valutazione finora

- Marketing Intelligence & Planning: Emerald Article: Value Equity in Event Planning: A Case Study of MacauDocumento16 pagineMarketing Intelligence & Planning: Emerald Article: Value Equity in Event Planning: A Case Study of MacauNikos FlagkakisNessuna valutazione finora

- Visitor Management: Lesson OutcomesDocumento22 pagineVisitor Management: Lesson OutcomesRubylene Jane Bactadan100% (2)

- Projrct Amusement 1Documento6 pagineProjrct Amusement 1Jagdish GuptaNessuna valutazione finora

- Grand Project On Amujment ParkDocumento144 pagineGrand Project On Amujment ParkJigar Bhavsar100% (3)

- The future of the European space sector: How to leverage Europe's technological leadership and boost investments for space ventures - Executive SummaryDa EverandThe future of the European space sector: How to leverage Europe's technological leadership and boost investments for space ventures - Executive SummaryNessuna valutazione finora

- The Structure and Performance of the Aerospace IndustryDa EverandThe Structure and Performance of the Aerospace IndustryNessuna valutazione finora

- Yum! Brands Group1 Final SummaryDocumento2 pagineYum! Brands Group1 Final SummaryCharlie RNessuna valutazione finora

- Homework 2Documento3 pagineHomework 2Charlie RNessuna valutazione finora

- Yum Brands MC Donals ExperienceDocumento2 pagineYum Brands MC Donals ExperienceCharlie RNessuna valutazione finora

- Tobacco CaseDocumento2 pagineTobacco CaseCharlie RNessuna valutazione finora

- Income Statement for Lawson Consulting P1Documento1 paginaIncome Statement for Lawson Consulting P1Charlie RNessuna valutazione finora

- Problem 8.1Documento1 paginaProblem 8.1Charlie RNessuna valutazione finora

- Sea Food Coments CaseDocumento1 paginaSea Food Coments CaseCharlie RNessuna valutazione finora

- Yum Brands MC Donals ExperienceDocumento2 pagineYum Brands MC Donals ExperienceCharlie RNessuna valutazione finora

- South West AirlinesDocumento2 pagineSouth West AirlinesCharlie RNessuna valutazione finora

- Solution 8.1Documento3 pagineSolution 8.1Charlie RNessuna valutazione finora

- Problem 8.2Documento2 pagineProblem 8.2Charlie RNessuna valutazione finora

- T-account balances homeworkDocumento2 pagineT-account balances homeworkCharlie RNessuna valutazione finora

- Ruth's Chris HawaiiDocumento1 paginaRuth's Chris HawaiiCharlie RNessuna valutazione finora

- Problem 8.3Documento1 paginaProblem 8.3Charlie RNessuna valutazione finora

- Problem 8.4Documento1 paginaProblem 8.4Charlie RNessuna valutazione finora

- Solution 8.2Documento2 pagineSolution 8.2Charlie RNessuna valutazione finora

- 9 Accounting HomeworkDocumento18 pagine9 Accounting HomeworkCharlie RNessuna valutazione finora

- QS 2-16 (Algo) Preparing A Statement of Owner's Equity LO P1Documento2 pagineQS 2-16 (Algo) Preparing A Statement of Owner's Equity LO P1Charlie RNessuna valutazione finora

- Visualizing Data with Charts and GraphsDocumento30 pagineVisualizing Data with Charts and GraphsCharlie RNessuna valutazione finora

- Notes CH 6Documento10 pagineNotes CH 6Charlie RNessuna valutazione finora

- Quiz Chapter 1 AnswersDocumento3 pagineQuiz Chapter 1 AnswersCharlie RNessuna valutazione finora

- 10 CH 1 Sumative QuizDocumento7 pagine10 CH 1 Sumative QuizCharlie RNessuna valutazione finora

- Homework AnswersDocumento6 pagineHomework AnswersCharlie RNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 2 NotesDocumento3 pagineChapter 2 NotesCharlie RNessuna valutazione finora

- 4 Chapter 1 - Introduction To StatisticsDocumento20 pagine4 Chapter 1 - Introduction To StatisticsCharlie RNessuna valutazione finora

- Restaurant Quality Rating and Meal Price AnalysisDocumento17 pagineRestaurant Quality Rating and Meal Price AnalysisCharlie RNessuna valutazione finora

- E. & J. Gallo Winery: C CA AS SE E S Sttu UD DYYDocumento4 pagineE. & J. Gallo Winery: C CA AS SE E S Sttu UD DYYCharlie RNessuna valutazione finora

- Coors Case StudyDocumento3 pagineCoors Case StudyJohn Aldridge Chew0% (1)

- Administracion Robbins Coulter 5ta EdDocumento836 pagineAdministracion Robbins Coulter 5ta EdAndres Mora Menendez81% (42)

- Marting Proposal For A Gluten-Free Flour Distribution Company in U.S. Executive SummaryDocumento5 pagineMarting Proposal For A Gluten-Free Flour Distribution Company in U.S. Executive SummaryCharlie RNessuna valutazione finora

- CPFR ModelDocumento10 pagineCPFR ModelUcheNessuna valutazione finora

- Final Project Inventory MGT at Malabar CementsDocumento50 pagineFinal Project Inventory MGT at Malabar CementsMahaManthra100% (1)

- A-Level: AccountingDocumento14 pagineA-Level: AccountingPrincess SevillaNessuna valutazione finora

- Business Performance EvaluationDocumento7 pagineBusiness Performance EvaluationMitchy torezzNessuna valutazione finora

- Midterm QuizDocumento10 pagineMidterm QuizEmmanuel VillafuerteNessuna valutazione finora

- Our AssignmentDocumento31 pagineOur AssignmentLavan SathaNessuna valutazione finora

- ReportDocumento21 pagineReportrpNessuna valutazione finora

- D-01 DPS IA Project 2017-001 Audit ReportDocumento19 pagineD-01 DPS IA Project 2017-001 Audit ReportABC 22/FOX 45Nessuna valutazione finora

- FIFO and Weighted AveDocumento2 pagineFIFO and Weighted AveMae MarinoNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Study on MIS in Restaurant Provides Insights into Strategic Planning, Managerial Control and Operational ControlDocumento5 pagineCase Study on MIS in Restaurant Provides Insights into Strategic Planning, Managerial Control and Operational ControlKing T. AnimeNessuna valutazione finora

- INTRO TO FINANCE COURSE OVERVIEWDocumento5 pagineINTRO TO FINANCE COURSE OVERVIEWSimeony SimeNessuna valutazione finora

- Sas#1 Acc100Documento14 pagineSas#1 Acc100Jhoylie BesinNessuna valutazione finora

- Operations Management Coursework on Supply Chain StrategiesDocumento12 pagineOperations Management Coursework on Supply Chain Strategiesdsfsdf sdfsdfNessuna valutazione finora

- Sitra Textile Industries LTDDocumento17 pagineSitra Textile Industries LTDHassan ZadaNessuna valutazione finora

- PHD On ERPDocumento5 paginePHD On ERPchennakrishnarameshNessuna valutazione finora

- The Utease CorporationDocumento8 pagineThe Utease CorporationFajar Hari Utomo0% (1)

- ch09 SolDocumento12 paginech09 SolJohn Nigz Payee100% (1)

- PIP - One Time CleansingDocumento5 paginePIP - One Time Cleansingcpscmain.supplyNessuna valutazione finora

- Operations Management NotesDocumento251 pagineOperations Management Notesfatsoe1100% (1)

- 201B Exam 3 PracticeDocumento16 pagine201B Exam 3 PracticeChanel NguyenNessuna valutazione finora

- Materials Management in Primary Health Centre: A Process MappingDocumento17 pagineMaterials Management in Primary Health Centre: A Process MappingAkansha JohnNessuna valutazione finora

- D7Documento11 pagineD7neo14Nessuna valutazione finora

- Concept PaperDocumento7 pagineConcept PaperPius VirtNessuna valutazione finora

- Function of Inventory ManagementDocumento11 pagineFunction of Inventory ManagementPrasad GharatNessuna valutazione finora

- SCM DeckDocumento3 pagineSCM DeckJignesh Sharad ModiNessuna valutazione finora

- Module 1 and 2 CFMADocumento74 pagineModule 1 and 2 CFMAk 3117Nessuna valutazione finora

- Cost Mock Compre With AnsDocumento15 pagineCost Mock Compre With Anssky dela cruzNessuna valutazione finora

- Job Order Costing SeatworkDocumento7 pagineJob Order Costing SeatworksarahbeeNessuna valutazione finora

- En Slimstock RetailDocumento2 pagineEn Slimstock RetailDinesh PatilNessuna valutazione finora

- Operation Management ReportDocumento14 pagineOperation Management ReportClaudia SmithNessuna valutazione finora