Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Immunitary Bioeconomy: The Economisation of Life in The International Cord Blood Market

Caricato da

Renata VilelaTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Immunitary Bioeconomy: The Economisation of Life in The International Cord Blood Market

Caricato da

Renata VilelaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Social Science & Medicine 72 (2011) 1115e1122

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Social Science & Medicine

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/socscimed

Immunitary bioeconomy: The economisation of life in the international cord

blood market

Nik Brown*, Laura Machin, Danae McLeod

Science and Technology Studies Unit, Department of Sociology, University of York, United Kingdom

a r t i c l e i n f o

a b s t r a c t

Article history:

Available online 13 February 2011

This paper examines an emerging bioeconomy centred on the international banking and trade in cord

blood. Since the late 1980s cord blood has been used in an expanding range of treatments and as an

alternative to the use of bone marrow stem cells. This is particularly the case in treating ethnic minority

populations who have historically been under-represented in bone marrow registries. The paper explores

the mobilisation and commercialisation of an increasingly important bioeconomic resource with cord

blood units trading internationally at high prices. This is a market mediated through a sophisticated

global network of immunologically typed and matched bodily matter in which immunity has become

a form of corporeal currency. Based on recent international gures we reect upon the balance of trade

between imports and exports across the worlds cord blood bioeconomy. Theoretically, this case is, we

suggest, an extension of what Roberto Esposito (2008) has termed an immunitary paradigm in which

immunity has become the basis for new forms of bioeconomic ow, circulation and exchange. Esposito

(2008). Bios: Biopolitics and Philosophy. Minnesota, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords:

Cord blood banking

Stem cells

Bioeconomy

Immunity

Ethnicity

Introduction and background to global cord blood banking

Recent decades have witnessed the emergence of newly globalised tissue economies (Waldby & Mitchell, 2006) with innovative industries established around the sourcing and economic

circulation of human tissues. These new economies are mediated

by a whole suite of infrastructural and bureaucratic systems enabling the exchange, reciprocity, regulation and brokerage of esh

and matter. Immunology and the matching of tissues and cells to be

used in treatment, or to re-engineer matter to induce immune

compatibility, has become central to these emerging markets.

While literature on the new tissue economies has either directly or

indirectly addressed what we might call the capitalisation of

immunology, less well understood are its links to the production

and orchestration of racially and ethnically devised bioeconomic

sovereign resources (see also Benjamin, 2009 and Whitmarsh,

2008).

This paper examines emerging architectures of biocapital

through the banking and international trade in cord blood (CB)

stem cells. It traces the commercialisation of cord blood and the

capitalisation of immunity in which CB has become a new form of

currency in the worlds international blood economies. CB is now

widely recognised as rich in haematopoietic stem cells (HSCs)

* Corresponding author.

E-mail address: nik.brown@york.ac.uk (N. Brown).

0277-9536/$ e see front matter 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.01.024

giving rise to the bodys entire blood and immune system. It has

been used clinically as an alternative to bone marrow for a range of

treatments since the late 1980s (Gluckman et al., 1989) with an

increasingly signicant prole in regenerative medicine (Brown,

Kraft, & Martin, 2006). This led to the establishment in the early

1990s of numerous international initiatives to source and bank CB

stem cells to be made available in a widening number of treatment

areas including cancer, immune system disorders and gene therapy.

Most of these public banks have been seen to operate within

a traditionally established discourse structured around giving, the

basis of a social solidarity where anonymous donors contribute to

a publicly available biological resource. Public blood economies

operate according to an allogeneic regime in which blood is more

usually circulated between unrelated though immunologically

matched donors and recipients.

There has also been a recent and rapid growth in a private CB

banking market with parents paying to deposit the stem cells of

their newborns for future private use (Brown & Kraft, 2006;

Waldby, 2006). Private banking has been the site of considerable

contention having been characterised as a neoliberal privatised

market where individuals or families make an exclusive claim on an

autologous (self-to-self) biological asset that remains private

property (Santoro, 2009). The cord blood debate has its history in

this binary polarisation of public and private economies, pitching

a solidaristic ethos of community inclusion against the atomistic

seclusion of the self (Titmuss, 1970).

1116

N. Brown et al. / Social Science & Medicine 72 (2011) 1115e1122

Nevertheless, this binary is far from straightforward and has

become increasingly unstable of late. Our focus here takes us

beyond a simple dichotomous division between the community

and the market, public and private. Instead we explore the banking

and international trade in CB between institutions that would

normally situate themselves organisationally within the terms of

public sector blood economies. This has been a sector highly

dependent on the availability of freely donated CB units within the

moral framework of altruistic giving. It is also a market model in

which the costs associated with storage are offset through pricing

strategies for blood products, particularly if those products can

attract a premium through international exportation.

The number of public and private CB banks operating internationally has risen sharply over the course of the last two decades

(Martin, Brown, & Turner, 2008). The World Marrow Donor Association lists close to half a million units of CB made available for

allogeneic treatment through fty six banks operating in thirty ve

countries (WMDA, 2008). The establishment of international

agencies and registries like the WMDA has been crucial in enabling

clinical groups and banks to liaise in arranging the purchasing of CB

units across and within international borders.

As we discuss below, CB is a high value commodity frequently

trading at 15,000 to 20,000 per unit. In a growing number of

cases patients receive costly multiple transplants to increase the

likelihood of therapeutic success (Hollands & McCauley, 2009). This

represents a substantial income for those banks selling CB given

that the cost of storage is, on average, considerably lower (usually

less than 10% of the export price). Based on units traded through

the WMDA, the international CB market was worth in excess of

20 m during 2008 and is rising sharply.

The global market in CB is also distinctive in a number of other

crucial respects. First, while traditional marrow registries are digital

libraries cataloguing immunologically typed potential donors, CB

banks by contrast store the physical substance itself. CB is more

amenable than bone marrow to off-the-shelf and on-demand

availability and circulation within a time sensitive system of distribution and exchange. As Waldby and Mitchell (2006) observe, . the

logic and rationale of a bank goes beyond storage and deposition e

but more crucially mobility and the readiness for withdrawal (p. 36).

Processing has been central to this accelerated mobilisation. Until

recently CB was often frozen whole but is now processed to reduce

volume, storage space and freight weight.

Second, while bone marrow donation involves invasive surgical

extraction with frequently long delays in scheduling, CB donors are

seen to incur far less risk, discomfort and inconvenience. Nonetheless, collection is not without contention, taking place amidst

the many competing clinical demands of the birthing process

(RCOG, 2006). Third, the use of CB as a substitute for bone marrow

in treatment is growing rapidly. There are in the region of fty

thousand blood stem cell transplants undertaken each year. Over

the course of the last decade, the number of CB units used in stem

cell transplantation has risen eightfold (WMDA, 2008) and marrow

transplants decreasing proportionately (Pamphilon, 2009). CB now

accounts for roughly twenty percent of all HSC transplants in

children with the number rising for adults. As one of our interviewees from a charitable sector bank put it, CB is taking off.

Conceptualising immunitary theory

The CB market we elaborate upon here relies upon a sophisticated global network of immunologically typed and matched

bodily matter. Using ever more sophisticated technologies for

genetically distinguishing between immunities, networks like the

WMDA link suppliers and clients, donors and recipients, with

increasingly meticulous biological precision.

Before discussing the CB economy in greater detail, we want to

elucidate on immunity in the biopolitical theorisation of advanced

post-industrial modernity. The trade in immunology is, we argue,

part of what Esposito (2006, 2008) refers to as nascent immunitary

paradigm, whereby politics, biology and economy have become

steadily more intertwined. In this case, the immunitary paradigm

takes the form of a trade in immunotypes, an internationalised

political economy built upon the capitalisation and globalisation of

diasporic immunity (by which we mean the dispersal and heterogenisation of populations upon which the CB trade is based). Forty

percent of all CB units used in treatment are traded across national

borders (Meijer et al., 2009, WMDA, 2008) following established

patterns of diasporic distribution.

For Haraway (1991) the immune system is . a plan for

meaningful action to construct and maintain the boundaries for

what may count as self and other in the dialectics of Western

biopolitics. (p. 204). Esposito (2006) recognises the potential of

immunological tolerance as the basis for productive forms of

association. Isnt it precisely the immunitary system. he writes,

that carries with it the possibility of organ transplants (p. 54)?

Political theory has tended to adopt a polar contrast between

immunity and community. However, Esposito seeks to reconceive

these binaries.

Immunitas and communitas have their common etymology in the

munus, literally meaning gift or obligation. Communitas expresses

the mutuality of the bond and reciprocity. Immunitas signals

a negative resistance to reciprocity, protection from obligation and

the commons. In both medical and juridical discourse, immunity is

a form of exemption or untouchability. Gift giving within the context

of an immunological regime can imply a diminishment of ones own

goods and in the ultimate analysis also of oneself (Esposito, 2006,

p. 50). Immunity traditionally conceived negates life and threatens

social circulation. Communitas and immunitas map directly onto the

equally traditional binaries of the blood economies with their

intellectual roots in Titmuss (1970) advocation of blood as a public

good shielded from the market. Community suggests forms of

association premised on common access insulated from property

and trade. The immunitary paradigm by contrast is seen to operate

on principles that undermine free association: protective defence,

proprietary claims to ones own biology, and the atomistic individualisation of privatisation.

However, Esposito (2008) questions this assumption and is

particularly keen to point to ways in which immunity creates the

conditions for new forms of circulation. In his writing, immunity and

community are far from polarised with gradations where some

forms of immunity can lead to productive association and ow

(transplantation for instance). He writes of generative hospitable

forms of immunity within an afrmative biopolitics where immunity becomes the power to preserve life (Esposito, 2008, p. 53e54).

The important point to take away from these reections is the

way immunity itself has become a corporeal resource and currency

for community. CB banks provide a form of immunologically based

protection or exemption for those fortunate enough to benet from

participation in the blood markets of advanced industrial bureaucratic economies. Whether private or public, such banks are

immunitary ventures, stockpiles of immunity. As we argue below,

the international trade in CB is not necessarily a freely given

expression of common community. It is instead a form of protection

for the trades participants from the vulnerabilities of being

dependent on an import market in premium goods. Being able to

export valuable units eases the cost burden associated with buying

CB on the international market. What we want to document in this

paper are the newly emerging arrangements for structuring the

availability and trade in, an immune-system resource that is the

basis of a globalised community built on CB.

N. Brown et al. / Social Science & Medicine 72 (2011) 1115e1122

Method

This project was funded by the UK Economic and Social

Research Council (ESRC) and explores changing patterns in the

organisation, donation and deposition of CB stem cells. Over a 14

month period (2009e2010), 51 qualitative, semi-structured interviews were conducted including site visits (total 14) with the

following groups: clinicians and researchers e including obstetric

services and stem cell bioscience researchers; policy makers and

regulators e both at the UK domestic, European and international

levels; interest groups e including members of royal colleges:

health advocacy groups and charities; and interviews with actual

and potential donors and depositors of umbilical CB. Interviewees

were identied and recruited through several routes including

direct contact with stakeholder organizations and searches of

scientic and policy literature. Actual and potential CB donors were

recruited through local and national childbirth support groups.

Ethical approval was sought from our home institution ethics

committee, our regional NHS Research Ethics Committee.

The political economy data detailing the relative cost of CB units

(storage, deposition, procurement cost and overseas trade) is drawn

from three sources including: interviews (procurement personnel,

bank and senior health service staff); grey literature and internal

documentation including recently commissioned government

reports; and quantitative data generated by the World Marrow

Donor Association documenting the release, importation and

exportation of CB units across nation state borders. The WMDA is

one of the few internationally recognised sources collecting and

producing annualised reports from 112 of 128 identied banks

operating worldwide. Our analysis recalculates this raw reported

data to produce the balance of trade percentage of exports relative to

imports for each participating country for the year 2008. Qualitative

date was analyzed using a software coding system (Atlas.ti) to

categorize the data according to a broad range of empirically driven

themes. The research thus combines qualitative interview data and

policy data to link cultural and economic dimensions of CB banking.

As a number of commentators have noted, economy and politics are

rarely considered together in sociological critiques of the biosciences (Cooper, 2008; Lemke, 2001; Waldby & Mitchell, 2006). This

case study makes a modest contribution to a growing literature

focussing on the economisation of human biological life.

Cord blood collection - assembling diasporic immunity

The emergence of the CB banking sector is, we suggest, coextensive with contemporary globalisation and unprecedented levels

of immunitary migration and heterogenisation. The uid spatial

distribution of immunity is written into the foundational logic of

the establishment of a public banking capacity. Most banks were

originally set up to overcome the disproportionately high representation of white Caucasian populations in traditional bone

marrow registries. Long established registries have had strong

historical penetration amongst advantaged middle class blood

donors but recruited less well beyond the mainstream demographic. Non-Caucasoid populations have generally been poorly

provided for in the treatment of leukaemia where the chances of

nding an immunologically appropriate bone marrow match

remain considerably lower than for majority (usually white) populations. Recent gures suggest that while it is possible to nd

a match for up to 75% of patients of Western European origin, that

gure falls to 20% or 30% for other ethnic groups (Meijer et al., 2009).

Beatty, Mori, and Milford (1995) were amongst the rst in the mid

1990s to draw attention to the diminishing probabilities of nding

appropriate bone marrow matches for those who self-reported

their ancestry as African American, Hispanic, Native-American and

1117

Asian-American. More recently, Kollman (2004), put the probability

of nding a suitable match within the US National registry at 27%,

45%, 75% and 48% for blacks, Asians/Pacic Islanders, whites and

Hispanics, respectively. (p. 89). As Navarrete and Contreras

(2009) explain the probability of nding an HLA matched unrelated donor depends not only on the degree and resolution. of the

HLA matching required but also on ethnic background. (p. 147).

While these factors alone have been important in animating the

establishment of CB banks, many of the sectors target populations

are also disproportionately subject to heritable blood related haemoglobinopathies (Atkin, Ahmad, & Anionwu, 1998). CB banks

were established to ll this gap, compensating for under-representation in the bone marrow registries with a readily available

stock in HSCs derived from minority populations. Investment has

been promoted within health services as an effort to remedy these

inherent inequities in bone marrow-based systems of circulation

and exchange:

. [minority populations] are disproportionately affected by the

difculties of obtaining bone marrow. And so theyre often

found looking and searching and not being able to nd the

appropriate match to help CB related disorders in the family.

Theres a recognition that theres been too little CB for groups

and the government have sought to tackle that. Now, the

collection points presently are supposed to try and meet that

need but I think its very limited (UK Member of Parliament 1).

The collection points mentioned here refer to the way otherwise

rare (and consequently high premium) CB units are sourced into the

system. The US National Marrow Donor Programme has focussed

intensely on recruiting from key minority populations including American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African

American, Hispanic or Latino, and Native Hawaiian or other Pacic

Islander (NMDP, 2009, p. 2). Elsewhere, the UK Cord Blood Bank

currently recruits potential donors from ve London hospitals with

considerably higher birth rates amongst ethnic minorities than

elsewhere. The rationale has been to maximise the statistical

possibility of collecting from racially heterogeneous collection sites,

rather than selecting minorities specically. Inclusion and exclusion

has both ethical and also scientic dimensions, as one respondent

put it: I dont think it would have been ethical to say were not

collecting from you. because that might have been the only

phenotype. even in caucasoids there are unique phenotypes.

(Director of a public CB bank 1).

In terms of the UK, while London has the highest density of nonCaucasoid candidate donors, other cities have also been cited as

potentially signicant recruitment sites should the service expand

to avoid dependence on overseas imports. As one UK Department

of Health interviewee put it: .we have to think about if we want

an ethnic mix that can only be got from North America. theres

a quid pro quo there. We have probably one of the most ethnically

mixed populations, especially in London, Liverpool, Manchester

and Cardiff. These were all once globally important port cities with

large West Indian, Afro-Caribbean and near Asian populations

dating back historically to the slave trade and the textile industries.

As one respondent put it, these are locations where health services

are seen to have good personal relations with potential donors

from racial minorities.

Interviewees from the UK Cord Blood bank estimate that around

40% of its units have been sourced from donors who self-report

themselves as non-Caucasoid. However, collecting from these

populations has also had unexpected implications for the business

model upon which many of the public banks were established. As

the following interviewee points out, the strategy was intended to

increase the therapeutic and also economic value of the collection.

But it has since become apparent that donated units from these

1118

N. Brown et al. / Social Science & Medicine 72 (2011) 1115e1122

populations had unusually low stem cell counts that threaten their

value as units of exchange in the global immunitary marketplace:

we have been very successful. forty percent of our collection is

from ethnic minorities. there has been a price that weve paid

for that in terms of business because weve. shown that those

from ethnic minorities have lower volume and lower TNCs

[Total Nucleated Cell count]. so a large number of our units are

considered not the optimal product. thats the price weve

paid. so from the business point of view weve not been all that

successful in selling them as it were. here is where you have to

balance the economics and the ethics (Director of a public CB

bank 1).

In terms of recruitment, the question of race has proven to be

acutely sensitive for populations with long established colonial

histories. For instance, staff frequently attribute fear and suspicion

to ethnic minority communities as a major obstacle to improving

donation rates. These are far from straightforward issues with

complex connotations suggesting many multiple meanings associated with donation including ambivalence and the threat of

appropriation (see also Whitmarsh, 2008):

. Ive sat and spoken to men and you kind of think they see the

light but they still dont want to donate. Now, is that because

they dont want to lose face? Is that because they really dont

understand whats being done?. just difcult trying to nd

a way in to that kind of group (Representative from a charitable

sector bank 1)

Its known that ethnic diversity is really something that needs

to be brought out in the open and say there arent enough ethnic

samples being stored and their chances of a match are even

slight. (Director of a private CB bank 1).

Heritability of genotypic immunity are constantly subject to

intergenerational and spatial redistribution continuous with postcolonialism and globalisation. It is that dynamism that has

provided the incentive for an international system of exchange

while at the same time turning it into a premium commodity

resource. CB banking brings into view dimensions of globalisation

directly linked to the vitalistic and corporeal. The migratory ow of

bodies is a diasporic dispersal of genetically indexed immunity.

Within the developing immunitary regime documented by Esposito and others, immune system biology has itself become the focus

for bioeconomic enterprise. Newly heterogeneous populations are

the driving demographic factors in encouraging health services

around the world, but particularly in North America, Europe and

East Asia to establish CB banks. For example, one of our respondents from the private banking sector here comments on the way

commercial banks have sought new markets amongst the migratory communities displaced by the transition of Hong Kong from

British to Chinese rule:

.When Hong Kong closed down. the rich Chinese. moved

to Toronto. but what you have then is a lot of mixed race

couples. [their] children are going to be. unusual genotype

and to get a transplant for that kind of child would be very

difcult. So private storage in that area is very popular.

(Director of private CB bank 2).

Race has a profoundly volatile place within a post-colonial

modernity characterised on the one hand by the varied instabilities

of diaspora, while also subject to new biometric measures for xing

and determining biological identity. The CB sector spans and utilises

any number of technologies where the geneticisation (Lupton,

1994) of race has been recently enlarged through population

genetics, racial proling, and genetic genealogical and ancestry

studies, etc. CB banking extends the way biological markers, within

this nascent immunitary paradigm, have begun to operate as an

important register of racial and ethnic difference (Reardon, 2005).

Registries: brokerage and standards in the immunitary

economy

The search for CB units for use in treatment is, in most circumstances, triggered by either a haematologist or oncologist

through referral to a transplant centre. In most country contexts,

searches are made rst of national registries before higher

premium and more costly international registries. The move

towards banking the physical substance of CB itself is in part driven

by an attempt to rationalise a highly complex process of searching,

matching and testing potential donors. As one respondent put it,

the established methods of procuring HSCs through existing bone

marrow registries entails a necessary and time-consuming gap

between the request for donation and the act of donation itself. This

becomes more complex as a search moves from the domestic to the

international level:

. I found donors for people where their immediate consultant

didnt know those donors existed. So. the system isnt as efcient as it could be . donors are not searched fast enough, or.

early enough. [T]he resources for looking for donors and for

testing potential donors are not as much as they could be. if

a patient in the UK has, I dont know, 10 matches overseas the

funds will only be available to test those one at a time, in many

instances (Director of a charity sector bank 2).

CB registries position themselves at the very centre of a vast

network linking donors, recipients, clinicians, banks and regulatory

agencies. As obligatory passage points (Callon, 1986), they mediate

the ow of CB between suppliers and consumers, banks and clinicians. While banks operate as repositories or stores of the immunitary economys principle asset, registries are the trading zones

(Galison, 1997) through which CB travels.

There are a number of such interlinking brokers operating

globally, though they are primarily concentrated in Europe (the

Netcord registry) and in the US (the Cord Blood Registry of the

National Marrow Donors Association). While registries are clearly

internationalised, they nevertheless have a regional orientation

partly premised on providing a trading advantage within a globally

competitive marketplace. For instance, the Eurocord registry of CB

transplants was established in 1995 primarily to keep pace with US

based infrastructures and has been nancially supported through

three successive rounds of European Commission funding. The

prospect of dependence on high cost imports from the US has been

repeatedly cited as grounds for the establishment of a Europeanwide bank. As one prominent advocate of European CB capacitybuilding recently put it, If nothing is done, we will have to rely on

US imports, which could cost $27,000, making transplants difcult

to afford. Also, ethnicity is rather different in the US compared to

the EU, (Gluckman, 2006). This question of the balance of trade

between different banking nations is explored in greater depth

below.

The crucial factor for registries is the question of scale. The larger

the collection, and the wider and more heterogeneous the network,

the more likely it is that a clinically useful match can be established

between donor and recipient. The advantage for any such registry

depends on its distributed geographical and tendrilous reach into

widely dispersed immunitary pools. It is less of a surprise then, that

while registries have something of an anchorage in the political

economies of regional blood economies, they are fundamentally

globally oriented in sourcing CB. As the following respondent

explains, the immunitary complexity of an outbred (the respondents phrase) globalisation in which populations have become

N. Brown et al. / Social Science & Medicine 72 (2011) 1115e1122

much more diverse means that very few national CB supplies are

varied enough to be able to meet domestic demand:

.the HLA is so polymorphic that no country would be able

to think itself sufcient even with the largest bank. thats why

you need the international collaboration. were maximising

the probabilities of nding a donor for the UK. countries set up

this registry to satisfy local need. we are all fully aware that we

will be providing for donors abroad as indeed beneting from

those donors in other registries. the gures with export/

import are quite clear. this is an international collaboration

(Director of a public CB bank 1).

The international market has come to depend fundamentally on

widely agreed standards whereby buyers and sellers can be assured

of the quality of assets traded. The immunitary economy we

describe here has been steadily built up through what Callon,

Meadel, and Rabeharisoa (2005) have termed an economy of

qualities. If race is the asset, standards measure of the worth of that

asset by attening the otherwise uneven spatial topographical

geography of the CB trading zone (Webster & Eriksson, 2008). One

UK transplant director put it that . it becomes a worldwide

resource. What we can offer in the UK is . lots of ethnic minorities.. Plus a system that will deliver quality.

There have been a number of overlapping and sometimes

competing initiatives to manage the variability of CB value

including the establishment of Netcord, FACT (Foundation for the

Accreditation of Cellular Therapy) and the efforts of the World

Marrow Donor Association. In addition to promoting clinical

effectiveness, standard-setting is indispensible to the functioning of

an exchange economy in which CB assets command high prices.

The promotion and facilitation of trade has been central to policymaking in this area as illustrated by the European Tissues and Cells

Directive adopted by the European Parliament in 2004. One of the

primary purposes of the Directive was to put in place the supporting infrastructure for a buoyant economic market in cells and

tissues across the eurozone. Nevertheless, while the international

distribution of the CB economy is vital to increasing the likelihood

of securing a close match, it necessarily highlights unevenness in

practise:

France is 22 miles away. South America is a 10 h ight. China is

14 h. You have very little control over what happens in other

jurisdictions and so internationally it really is a case of the will

to ensure that best practise is put in place and consent issues are

followed. And I think the one way we can do it is by saying that if

you are going to import material from elsewhere, its your

responsibility to ensure that that has been procured in a way

that you would expect it to be procured in the UK. Outside

theres not much we can do (Senior UK health service policy

maker 1).

Standards extend the immunitary paradigm by creating spaces

protected from pollution. In writing of contamination, Esposito has

in mind the state-orchestrated biopolitics of, for example, immunitary protection from interhuman contamination that underpins

immigration policy. He writes that the prevention of contamination

has its apex in our own time, and no more so than in a biopolitical

economy dependent on the free circulation and exchange of disembodied mobile matter, cells and tissues. Standards in these terms

operate to dene inclusion and membership of an immune-based

community offering protection from potential contamination

across the blood economies. Registries illustrate these efforts to

establish an immunitary community perfectly. But taken too far,

protection from contamination can result in a negation of life. The

immunitary paradigm can work to restrict the circulation of ow.

For example, government legislation and the registries themselves

1119

have had to be cautious in balancing the stringency of standards in

order to avoid complete exclusion of potential participants from the

CB sector.

The immunitary balance of trade

The international economy in CB is a trade that largely advantages those countries able to capitalise on a higher ratio of exports

to imports. In other words, a balance of trade surplus allows trading

nations to derive economic value from premium payments on

units. This globally oriented feature of the market extracts a bioeconomic surplus value (Cooper, 2008) from CB that substantially

exceeds its value within internal domestic contexts. The high cost

premium attached to international trade is a strong incentive for

the establishment of more comprehensive domestic supplies, and

this has become a pressing political and health economic question

as pointed out by the following respondent, a parliamentary

member of the UKs All party group on clinical CB and adult stem

cells:

.theres an issue of domestically how we do that [generate

supply] and the cost of importing CB. And that has an impact on

the Health Service. If we can ensure that we have home-grown

CB that must be cheaper. A good percentage of transplanted CB

is from abroad and that costs money. So the purpose of this is to

save lives and saving lives does save money as well because it

saves the costs of care. (UK Member of Parliament 1).

The costs associated with banking CB vary considerably but

generally do not exceed 2000. The UK NHS bank (NHS CBB) estimates the cost of unrelated (allogeneic) collection to be in the

region of 1400. Rates paid by private depositors to commercial

banks are fairly similar. However, the costs of purchasing CB

through international registries are very signicantly higher. Both

the UK based charity, the Anthony Nolan Trust, and the NHS CBB

pay in the region of 17,000 or more per unit imported from

overseas. Where multiple units have to be used to treat single

patients, as in the treatment of older children and adults, the costs

of a viable match on the international market can be prohibitively

expensive. It is less of a surprise that many banks have based their

business model on an export rather than import market:

. there are banks collecting as much as possible knowing that

its not for their own patients but for exporting them [so] they

can fund their own banks, if you think of it as a business, they

might be able to become economically self-sufcient but you

will never be able to be self-sufcient from the clinical point of

view (Director of a public CB bank 1).

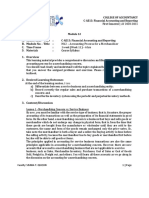

There are very few data sources documenting international

markets in CB but gures generated by the WMDA (2008) represent

the most comprehensive source of information on the release,

usage and destination of units. Based on the reported quantitative

survey data for banks operating in each country it is possible to

generate a calculation of the balance of trade between participating

countries (see Fig. 1). A cluster of countries can be seen to trade

relatively high volumes of CB units across their borders (>50). Of

these, a number operate a signicant trade surplus where exports

exceed imports. For example, of the 137 units traded by Germany in

2008, the vast majority of these (110 or 80%) were exported overseas. Other countries operating a signicant surplus include

Belgium (86%), Australia (83%), and the US at 512 units or 68% of

cross-border trade. The objective for most domestic haematological

services has been to maximise exports and increasing value

through quality control but more importantly through racial and

ethnic variation.

1120

N. Brown et al. / Social Science & Medicine 72 (2011) 1115e1122

Cord blood

exported (%)

512 (68)

74 (23)

123 (58)

94 (52)

133 (83)

110 (80)

37 (29)

0

68 (86)

0 (0)

18 (44)

8 (24)

13 (43)

18 (82)

2 (10)

7 (37)

0

8 (62)

0

0

2 (29)

0

5 (100)

1 (25)

2 (100)

0

0 (0)

0 (0)

Country

US

France

Spain

Italy

Australia

Germany

UK

Canada

Belgium

Brazil

Netherlands

Israel

Switzerland

Taiwan

Mexico

Singapore

Greece

Czech R

Sweden

Argentina

Finland

Austria

Japan

Poland

Korea

Turkey

China

Hong Kong

Imported (%)

236 (32)

247 (77)

90 (42)

86 (48)

28 (17)

27 (20)

91 (71)

86 (100)

11 (14)

44 (100)

23 (56)

25 (76)

17 (57)

4 (18)

18 (90)

12 (63)

18 (100)

5 (38)

11 (100)

10 (100)

5 (71)

7 (100)

0 (0)

3 (75)

0 (0)

2 (100)

1 (100)

1 (100)

Totals traded

% Exported of

those released

36

35

69

67

75

87

79

0

92

0

95

80

100

23

5

37

0

100

0

0

33

0

4

100

3

0

0

0

748

321

213

180

161

137

128

86

79

44

41

33

30

22

20

19

18

13

11

10

7

7

5

4

2

2

1

1

Fig. 1. Balance of trade.

The global patterning of the CB bioeconomy directly reects

population heterogeneity. Most East Asian countries, for example,

are predominantly self-sufcient in the supply reecting, it is

argued, the internally homogeneous composition of both their

populations and their blood economies. Japan, Korea, China and

Hong Kong source their CB almost exclusively through domestic

supply (see Fig. 2) with the exception of Taiwan. Of the 138 units

released for treatment in Japan, none were imported and only 5

exported. Asia then tends to have an internally-oriented supply

chain removed from the international export market and is

predominantly self sufcient. As one recent report explains it: .

Japan exports hardly any samples, as their specic HLA types are

endemic to Japan (Meijer, et al., 2009, p. 37) This is a radical

contrast to Europe and North America more strongly integrated

into globalised histories of migration and immunitary diversity. An

outbred genetic pool is the raw material foundation for international capitalisation and the extraction of surplus value. But as

the following respondent suggests, the more outbred a population,

the greater is the requirement to go beyond the nation state in the

search for immunitary resources:

Country

Japan

Taiwan

Korea

China

Hong

Kong

Exported

Released

5

18

2

0

138

77

62

18

11

Released

for

domestic

use

133

29

60

18

11

I dont think theres one country that can be self-sufcient. the

only country is Japan because theyre such a homogeneous

group. there may be other countries that are less diverse but if

you look at Europe and the prole of the population theyre very

outbred and you wont get a [single] bank that will provide you

with that (Director of a public CB bank 1).

The majority of countries operating through the WMDA (64% of

the sample in Fig. 1) operate a trade decit with imports exceeding

exports. Countries with signicant decits include Canada (100%),

France (77%) and the UK (71%). Countries trading fewer than 50

units but operating a trade decit include Mexico (90%), Israel

(76%), Poland (75%) and Finland (71%). The question facing countries in this group is whether the cost of relying on imports is less or

greater than the likely costs of increased investment in domestic CB

banking. For instance, if we conservatively estimate that the 86

units imported into Canada during 2008 had a market value of

$20,000 each, import costs for 2008 would total over $1.7 m. Those

costs are unlikely to be borne by a single health services provider

and there are a wide range of factors at stake in whether or not

%

Exported

of those

released

4

23

3

0

0

Fig. 2. Markets in Asia.

Available

Units

used

Imported

5455

42135

100545

8892

133

33

60

19

0

4

0

1

2885

12

N. Brown et al. / Social Science & Medicine 72 (2011) 1115e1122

Country

Available

Exported

Released

France

Germany

Australia

Belgium

Switzerland

Italy

US

UK

Spain

7051

18557

20044

14533

2212

17503

154749

10589

35802

74

110

133

68

13

94

512

37

123

212

127

178

74

13

141

1428

47

179

Released

for

domestic

use

138

17

45

6

0

47

946

10

56

%

Exported

of those

released

35

87

75

92

100

67

36

79

69

1121

Units

used

Imported

385

44

73

17

17

133

1182

101

146

247

27

28

11

17

86

236

91

90

Fig. 3. Units available to those traded.

individual countries take the initiative to offset import costs

through domestic supply. Much depends on variables beyond the

scope of this paper including the structure of health service organisation and the arrangement of funding mechanisms in individual

countries.

Another interesting feature of the CB economy highlighted by the

data is that the difference between those countries that export

a high number of units, and those exporting comparably few, has

less to do with the number of units available, and more to do with

their ethnic/racial diversity of individual banks. UK CB public

collection was actually relatively small in 2008 by international

standards (10,589 compared with Germany [18,557], Australia

[20,044], Belgium [14,533], Italy [17,503]). However, the majority of

UK CB released for treatment went overseas (see Fig. 3). Thirty seven

of the forty seven (79%) units it released were exported, a gure

attributable to the very high success rate of the bank in recruiting

from racial minority populations. Navarrete and Contreras (2009)

calculate that .36% of units issued from the UK bank for transplantation are from ethnic minorities (p. 238). It is probable that

a similarly proportionate percentage of the units exported are also

sources from minority populations. The UK is estimated to have the

second highest percentage of rare immunities (41%) across global

registries (Pamphilon, Regan, Navarrete, & Watt, 2009). So while CB

may indeed be the raw material of the market, the actual asset is

constructed as race itself. The immunitary trade signicantly

advantages those racially heterogeneous countries able to supply

globally dispersed populations.

Nevertheless, strong exporters are not necessarily very successful at supplying their own domestic demands. Whereas the UK

exported 37 of 47 released, it imported 91 units at an estimable cost

of around 1.5 m, paying nearly three times in import costs what

it earns from exports. Most sizeable exporters are much more

successful at supplying their own demand. Imports as a proportion

of units used in treatment are generally lower than in the UK and

account for between 20% and 64% (US and France respectively) for

most other countries in Fig. 3. The trend over the course of the last

decade or so has been to see a rising dependence in Europe on

imports, a tendency now motivating stronger investment in regional CB capacity (Pamphilon, 2009). Indeed, a number of countries

have provisions to protect domestic supply from export. For

example, Spain allows the export of CB on the condition that it can

be shown that the unit does not have any current utility within its

national borders. Like other competitive areas of trade, the CB bioeconomy is characterised by mechanisms that both facilitate ow,

while also protecting national ownership. As one commentator puts

it, there is muted competition between the public banks themselves

seeking to achieve a critical size (Katz-Benichou, 2007, p. 464). The

balance of trade in CB maps onto other similar tensions between

sovereign autonomy and yet global dependence where post-colonial countries engage in the capitalisation of ethnically or racially

produced resources including, for example, pharmaceutical investment in ethnic drug markets (Benjamin, 2009; Whitmarsh, 2008).

The destination countries to which CB is exported are also

highly signicant. The single highest export destination is the US,

probably the most racially heterogeneous of the trading nations, on

average accounting for roughly 30% of all exports. A notable

exception is the absence of sub-Saharan Africa from these gures,

excluded from prohibitively expensive premium markets and

reecting the global patterning of traditional blood services with

trade mainly concentrated in and between afuent advanced

industrial bureaucracies.

Conclusion

CB presents both opportunities and challenges to the international organisation of blood and is profoundly telling of changes in

the global economisation of disembodied human matter. To return

to Esposito, the CB case eshes out, so to speak, his version of

biopolitics as an immunitary paradigm. Communitas and immunitas

express the changing characteristics of order and organisation in

todays biopolitics. Communitas in its traditional meaning is associated with gift and giving but carries with it various risks. Gifts

may be costly and go unreciprocated and there may be tensions

between competing interests (the individual and the community,

the state and the wider global commons). Immunitas develops as

a means of protection from these risks, methods for self-defence

from the otherwise boundless or insatiable demands of community. While immunitas has its roots in communitas it develops an

alternative logic replacing the gift economy with private markets

based on nancial exchange, trade and the contract. The immunitary paradigm expresses this translation of blood and gift into

a global immune-based economy. The immunitary has a double

valency here signalling a system of value, circulation and ow, but

also the predication of the bioeconomy on genotypic immunity.

Biology and life itself, rather than labour, is increasingly recognised as central to the production of surplus value in the contemporary tissue economies. Within this relatively new framework,

bioeconomisation is seen to efface the boundaries between the

spheres of production and reproduction, labour and life, the market

and living tissues (Cooper, 2008, p. 9). However, it is in fact the

dispersed internationalisation of these bioeconomies that allows

for the multiplication of value that we can observe as CB units are

traded across state borders.

One of the more signicant aspects of the story told here is the

way a surplus value is derived from CB in two complementary and

interlinked ways. First, internationalisation is essential to biovalue

production because of the need to seek out widely dispersed

immunotypes. The global nature of matching across highly heterogenised immunities necessitates a widely distantiated reach

through networks like that of the WMDA. The probabilities of

1122

N. Brown et al. / Social Science & Medicine 72 (2011) 1115e1122

obtaining exactly the right match may be vanishingly small and

only ever possible where spatial reach has been widened sufciently to improve the statistical likelihood of securing a match. In

this sense, the bioeconomy we document here extends and capitalises upon an immunitary globalisation, historically structured

through outbred diasporic migration.

Second, internationalisation allows for the additional extraction

of a monetary surplus by permitting an economic value to be

negotiated and attached to CB units. Over and above the original

costs associated with extraction and banking, internationalisation

enables added indirect costs to be folded into prices set for CB in the

global marketplace. That prot surplus is legitimated on the basis

that blood services should be able to offset costs and compensate

themselves for the economic risks and nancial burden of domestic

collection and storage.

Our focus here has been to elaborate on the international

political economy of life by documenting the production of an

increasingly vibrant market in CB stem cells. In so doing, we have

also sought to respond to the contention that social critique of the

biosciences has neglected economisation and too readily focused

on politicisation (Cooper, 2008; Lemke, 2001). It remains to be seen

how the economic realities of an international trade in blood are to

be reconciled with an enduring cultural attachment to a moral

economy of values where altruism and gift remain the primary

symbolic motivation for sourcing premium bioeconomic resources.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Paul Martin, Naomi Pfeffer,

Daryl Martin and Andrew Webster whose reections on an earlier

version of this paper proved invaluable. Our research was kindly

funded by the UK Economic and Social Research Council RES062-23-1386. We would like to thank the World Marrow Donor

Association for sharing with us their 2008 annual cord blood

survey.

References

Atkin, K., Ahmad, W., & Anionwu, E. (1998). Screening and counselling for sickle cell

disorders and thalassaemia: the experience of parents and health professionals.

Social Science & Medicine, 47(11), 1639e1651.

Beatty, P. G., Mori, M., & Milford, E. (1995). Impact of racial genetic polymorphism upon

the probability of nding an HLA-matched donor. Transplantation, 60(8), 778e783.

Benjamin, R. (2009). A lab of their own: genomic sovereignty as postcolonial

science policy. Policy and Society, 28, 341e355.

Brown, N., & Kraft, A. (2006). Blood ties: banking the stem cell promise. Technology

Analysis and Strategic Management, 18, 313e327.

Brown, N., Kraft, A., & Martin, P. (2006). The promissory pasts of blood stem cells.

Biosocieties, 1, 329e348.

Callon, M. (1986). Elements of a sociology of translation: domestication of the

scallops and the shermen of St Brieuc Bay. In J. Law (Ed.), Power, action and

belief: A new sociology of knowledge? (pp. 196e233). London: Routledge.

Callon, M., Meadel, C., & Rabeharisoa, V. (2005). The economy of qualities. In

A. Barry, & D. Slater (Eds.), The technological economy (pp. 28e50). London:

Routledge.

Cooper, M. (2008). Life as surplus: Biotechnology and capitalism in the neoliberal era.

Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Esposito, R. (2006). Interview. Diacritics, 36(2), 49e56.

Esposito, R. (2008). Bios: Biopolitics and philosophy. Minnesota, MN: University of

Minnesota Press.

Galison, P. (1997). Image and logic. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Gluckman, E., Broxmeyer, H. A., Auerbach, A. D., Friedman, H. S., Douglas, G. W.,

Devergie, A., et al. (1989). Hematopoietic reconstitution in a patient with Fanconis

anemia by means of umbilical-cord blood from an HLA-identical sibling. New

England Journal of Medicine, 321, 1174e1178.

Gluckman, E. (2006). Expert issues appeal for FP7 stem cell funding. Times Higher

Educational Supplement, . Feb 2nd, Retrieved from. www.timeshighereducation.

co.uk.

Haraway, D. J. (1991). Simians, cyborgs, and women: The reinvention of nature. London:

Free Association Books.

Hollands, P., & McCauley, C. (2009). Private cord blood banking: current use and

clinical future. Stem Cell Reviews and Reports, 5, 195e203.

Katz-Benichou, G. (2007). Umbilical cord blood banking: economic and therapeutic

challenges. International Journal of Healthcare Technology and Management, 8(5),

464e477.

Kollman, C. (2004). Assessment of optimal size and composition of the U.S. national

registry of hematopoietic stem cell donors. Transplantation, 78(1), 89e95.

Lemke, T. (2001). The birth of bio-politics: Michel Foucaults lecture at the college

de France on neo-liberal governmentality. Economy and Society, 30(2), 190e207.

Lupton, D. (1994). Medicine as culture: Illness, disease and the body in western societies. London: Sage Publications.

Martin, P., Brown, N., & Turner, A. (2008). Capitalising hope: the commercial

development of umbilical cord blood stem cell banking. New Genetics and

Society, 27(2), 127e143.

Meijer, I., Knight, M., Mattson, P., Mostert, B., Simmonds, P., & Vullings, W. (2009).

Cord blood banking in the UK: an international comparison of policy and

practice. technopolis group. Retrieved from. www.technopolis-group.com.

National Marrow Donor Programme. (2009). Fact and gures. http://www.marrow.

org/NEWS/MEDIA/Facts_and_Figures/FactFigures2009.pdf.

Navarrete, C., & Contreras, M. (2009). Cord blood banking: a historical perspective.

British Journal of Haematology, 147, 236e245.

Pamphilon, D. (2009). Quality approaches in cell therapy: patient and therapyrelated aspects. International society of blood transfusion. ISBT Science Series, 4,

24e30.

Pamphilon, D., Regan, F., Navarrete, C., & Watt, S. (2009). The NHS cord blood bank e

a vital resource for cell therapy. Blood and Transplant Matters, 29, 14e15.

Reardon, J. (2005). Race to the nish: Identity and governance in an age of genomics.

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Rcog - The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. (2006). Umbilical cord

blood banking. scientic advisory committee opinion paper 2. London: RCOG.

Retrieved from. http://www.rcog.org.uk/womens-health/clinical-guidance/

umbilical-cord-blood-banking.

Santoro, P. (2009). From (public?) waste to (private?) value: the regulation of

private cord blood banking in Spain. Science Studies, 22(1), 2e23.

Titmuss, R. (1970). The gift relationship: From human blood to social policy. London:

LSE Books.

Waldby, C. (2006). Umbilical cord blood: from social gift to venture capital. Biosocieties, 1, 55e70.

Waldby, C., & Mitchell, R. (2006). Tissue economies: blood, organs and cell lines in late

capitalism. London: Duke University Press.

Webster, A., & Eriksson, L. (2008). Governance-by-standards in the eld of stem

cells: managing uncertainty in the world of basic innovation. New Genetics and

Society, 27, 99e111.

Whitmarsh, I. (2008). Biomedical ambiguity: Race, asthma and the contested meaning

of genetic research in the caribbean. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

WMDA. (2008). Unrelated cord blood banks/registries annual report 2008 (10th ed.).

(Non-public domain document).

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Fundações de Torres Eólicas - Estudo de Caso: January 2013Documento13 pagineFundações de Torres Eólicas - Estudo de Caso: January 2013Renata VilelaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Alienation of BodyDocumento30 pagineThe Alienation of BodyRenata VilelaNessuna valutazione finora

- TextsLaw Topology and ComplexityDocumento10 pagineTextsLaw Topology and ComplexityJorge Castillo-SepúlvedaNessuna valutazione finora

- Foucault As Theorist of TechnologyDocumento9 pagineFoucault As Theorist of TechnologyRenata VilelaNessuna valutazione finora

- Cord Blood in Vitro Growth of Granulocytic Colonies From Circulating Cells in HumanDocumento6 pagineCord Blood in Vitro Growth of Granulocytic Colonies From Circulating Cells in HumanRenata VilelaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- SGR WAGH Bills of Exchange Full - 20210819 - 210205Documento59 pagineSGR WAGH Bills of Exchange Full - 20210819 - 210205UrfiNessuna valutazione finora

- Inventory QuesDocumento1 paginaInventory QuesYashi GuptaNessuna valutazione finora

- International Trade 4th Edition Feenstra Test Bank 1Documento37 pagineInternational Trade 4th Edition Feenstra Test Bank 1hazel100% (45)

- Bank Recon and POC ProblemsDocumento3 pagineBank Recon and POC ProblemsJanine IgdalinoNessuna valutazione finora

- Project Appraisal TechniquesDocumento6 pagineProject Appraisal TechniquesChristinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Prelim Task De-Vera Angela-KyleDocumento6 paginePrelim Task De-Vera Angela-KyleJohn Francis RosasNessuna valutazione finora

- PT - Java Agro Prima: JL. Jalan Bhayangkara Wates Yogyakarta, IndonesiaDocumento5 paginePT - Java Agro Prima: JL. Jalan Bhayangkara Wates Yogyakarta, Indonesiajk kedaiNessuna valutazione finora

- Sap MM Business Blue Print - SampleDocumento78 pagineSap MM Business Blue Print - SampleSuvendu Bishoyi100% (20)

- Forex Power Point PresentationDocumento20 pagineForex Power Point PresentationfarrilNessuna valutazione finora

- Your Airbnb ReceiptDocumento1 paginaYour Airbnb ReceiptAnurag Kumar ReloadedNessuna valutazione finora

- Place of SupplyDocumento66 paginePlace of SupplydataprotaxNessuna valutazione finora

- Foreign Trade Policy 2023Documento112 pagineForeign Trade Policy 2023Doond adminNessuna valutazione finora

- Transport Peer Graded Assignment CourseraDocumento5 pagineTransport Peer Graded Assignment CourseraAayush ThakurNessuna valutazione finora

- Sandesh Stores AuditedDocumento7 pagineSandesh Stores AuditedManoj gurungNessuna valutazione finora

- Rimex: Commercial InvoiceDocumento2 pagineRimex: Commercial Invoiceadi kristianNessuna valutazione finora

- BeanFX Iyanu Strategy - FX Traders BlogDocumento20 pagineBeanFX Iyanu Strategy - FX Traders BlogPagalavanNessuna valutazione finora

- Vietnam - Local Charges Cma - CGMDocumento1 paginaVietnam - Local Charges Cma - CGM5th07nov3mb2rNessuna valutazione finora

- Module 12 - Accounting Process For A Merchandising EntityDocumento8 pagineModule 12 - Accounting Process For A Merchandising EntityNina AlexineNessuna valutazione finora

- 2023 ObaDocumento27 pagine2023 ObaNicoNoelCavada-GuillermoNessuna valutazione finora

- PrakasamDocumento58 paginePrakasamTurumella VasuNessuna valutazione finora

- Solution Manual For International Economics 13th Edition Dominick SalvatoreDocumento10 pagineSolution Manual For International Economics 13th Edition Dominick SalvatoreReginald Sanchez100% (32)

- Maec 603Documento4 pagineMaec 603Sunder SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- 13-Pak-China FTA Report Final Version 4Documento149 pagine13-Pak-China FTA Report Final Version 4suksukNessuna valutazione finora

- Globalisation in Nepal Assessment of Achievements and The Way ForwardDocumento8 pagineGlobalisation in Nepal Assessment of Achievements and The Way ForwardMahendra ChhetriNessuna valutazione finora

- Factors Affecting Fluctuations in China's Aquatic Product Exports To Japan, The USA, South Korea, Southeast Asia, and The EUDocumento27 pagineFactors Affecting Fluctuations in China's Aquatic Product Exports To Japan, The USA, South Korea, Southeast Asia, and The EUnhathong.172Nessuna valutazione finora

- Incometax Automatic Calculator With Form-16 For 2017-18 EDNNET Version 8.3Documento30 pagineIncometax Automatic Calculator With Form-16 For 2017-18 EDNNET Version 8.3ragvijNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit Test 9: Answer All Thirty Questions. There Is One Mark Per QuestionDocumento3 pagineUnit Test 9: Answer All Thirty Questions. There Is One Mark Per QuestionSerNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Study How To Take Friction Out of CommerceDocumento19 pagineCase Study How To Take Friction Out of CommerceEv SaunièreNessuna valutazione finora

- Week 11 - Test BankDocumento59 pagineWeek 11 - Test Banklala azzahraNessuna valutazione finora

- Foreign Exchange Management Act, 2000: Presented By: Akanksha MalhotraDocumento19 pagineForeign Exchange Management Act, 2000: Presented By: Akanksha MalhotraGaurav KumarNessuna valutazione finora