Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Depression

Caricato da

killer008Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Depression

Caricato da

killer008Copyright:

Formati disponibili

156

Developmental

Psychopathology

events, depressed youth are less able' to generate effective solutions to interpersonal problems. Consistent with this hypothesis, depressed children have

poorer social skills (Bell-Dolan, Reaven, & Peterson,

1993) and they are less often chosen as playmates

or workmates by other ~hildren (R~d~IRh, Hammen.

& Burge, 1994).

Are depressed children the victims or the initiators of negative social relationshipf? An ingenious

study by Altmann and Gotlib (19881 investigated the

social behavior of depressed school-age children by

observing them in a natural setting: at play during

recess. The authors found that depressed children

initiated play and made overtures for social contact

et least as much as did nondepressed children, and

were approached by other children just as often. Yet,

depressed children ended up spending most of their

time alone .. By carefully observing the sequential

exchanges between children, the researchers discovered the reason for this. Depressed children were

more likely to respond to their peers with what

was termed "negative/aggressive"

behavior: hitting,

name-calling, being verbally or physically abusive.

These observations fit well with the model de,

veloped by Patterson and. Capaldi (1990), in which

peer relations are posited to play the role of mediators of depression. According to this model, a negative family environment leads children prone to depression to enter school with low self-esteem; poor

interpersonal skills, aggressiveness, and a negative

cognitive style. They are less able to perceive constructive solutions to social problems' andale more

likely to be rejected by peers because of the way

they behave. Peer rejection, in turn, increases their

negative view of self and thus their depression.

In order to test this model, Capaldi (1991, 1992)

differentiated four groups of boys depending on

whether they demonstrated aggression, depressed

mood, both aggression and depression, or neither.

Boys were followed over a two-year period. from

grades 6 to . While depression and adjustment

problems t ded to abate over time in the depressed

group, no such improvement occurred in the. two

other'

bed groups. While, in general; aggressive behavior was more stable than depressed

mood, condu t problems increased the risk of subsequen

having a depressive mood. In fact, ag-

gression in grade 6 predicted depressed mood in

grade 8, while earlier depression did not predict

later conduct problems.

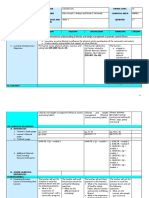

Capaldi conceptualizes the process leading from

aggression to depression as follows. (See Figure

7.3.) Aggression and noxious behavior. alienates parents, peers, and teachers, resulting in more interpersonal conflict and rejection. Further, a~agreSSiOn

leads to oppositional behavior in the cl sroom,

which leads to learning deficits and poor kill development. Both of these factors result in profound

failure experiences in the social and academic

realms. Failure and rejection, in turn, produce low

self-esteer;z. The impact of peer rejection. low academic skills, and low self-esteem is associated with

increasingly serious deficits in adolescence, ultimately resulting in depression.

The Organic Context

Evidence that organic factors play an important etiological role in depression has emerged in studies of

_adult populations, while research evidence in regard

to children is slight. (Our presentation follows Hammen .and Rudolph, 1996. unless otherwise noted.)

Familial concordance rates provide evidence for

agenetic component in depression. Children, adolescents, and adults who have close relatives with

depression are at considerable risk for developing

depression themselves. In fact, having a depressed

parent is the single best predictor of whether a child

. will become depressed.

However, simply demonstrating a correlation between parent and child depression fails to disentangle the relative influence of heredity and environ-

ment. For this, twin and adoption studies are needed.

One study of adolescents compared monozygotic and

dizygotic twins, biological siblings, half-siblings,

and biologically unrelated step-siblings and found

significant genetic influences at lower levels of depression but significant environmental influences at

high levels of depression (Rendeet 81., 1993). Another study investigated a large sample of monozygotic and dizygotic twin pairs agedS to 16 years

(Thapar & McGuffin, 1996). While environmental

factors seemed to best account for depression in

childhood, evidence for a genetic component was

strong in adolescence. In sum, while data support th~

-.'

,

I

,

I-

I-

Chapter

Figure

7.3

Soun:e: Adapted

Mediators

from Patterson

Disorders in the Depressive Spectrum

and Child and Adolescent

Suicide

157

of the .Effects of Child and Family. Factors on Depression.

and Capaldi.

1990

theory of a genetic component to depression in adults

andadolescents, other factors also playa major role

in the etiology of depression in children.

Research with adults indicates a neuroendocrine

imbalance as an etiological agent;' particularly hypersecretion of the hormone cortisol. This is not surprising since hormone production regulates mood,

appetite, and arousal. all of which are adverselyaffected by depression. However, little evidence exists for the role of cortisol in child depression.

Depression is also associated with low levels

of the neurotransmitter serotonin. Antidepressant

medications that act to increase serotonin _availability. including tricyclics such as imipramine and

the new generation -of selective serotonin reuptake

inhibitors (SSRIs). such as Prozac, have been proven

effective in combating depression in adults. Again.

however. evidence in support of this mechanism

in children is mixed at best. In many controlled

studies. antidepressant medications have not been

effective in combating child depression. Fisher

and Fisher (1996) reviewed thirteen double-blind

placebo-controlled studies published between 1965

and 1994 and found only two cases in whicli antidepressants relieved depression better than placebos. In fact, some studies seemed to shoW"that the

placebo was more effective! Similar null findings

are reported in an exhaustive review by SommersFlanagan and Sommers-Flanagan (1996).

Much of the research these investigators reviewed was based on -the older type of antidepressants rather than the new SSRIs. which may

be both more effective and safer. Recent studies

focusing on the efficacy of SSRIs in child and

158

Developmental

Psychopathology

Cognitive

representations

seff, others

of

, Faroily'-'-~_

e,xp~rie~

T"-

~I

Ufe

stress

~--~--~~-.------"

l~erjiersonal

"., ..

..

,. ~C'C?",petence

,

Figure

7.4

Hammen's

:';

Multifactorial

Transactional

Model of Child and Adolescent Depression.

Source: Hammen and Rudolph. 1996

adolescent depression are somewhat more promising (DeVane & Sallee, i996). However, effect

sizes are ,still small, and in some studies results

emerged only for ratings of global improvement

and not for symptoms of depression (Emslie, Kennard, & Kowatch, i995).

In summary, research on child depression, while

limited, suggests that organic theories of etiology

derived from studies of adults cannot be applied as

easily to children. Further, without prospective data

demonstrating that biological indicators predate the

onset of depression, there remains some question as

to whether these are the cause or result of depression, Ultimately, the picture is likely to be a complex and transactional one. Experiences and mood

act on biology, and, in turn, biology reciprocally affect cognitions, emotions, and memory (Post &

Weiss, 1997).

Integrative Developmental Model

A comprehensi e developmental psychopathology

model of depression has been put forward by Hammen (1991, i992; Hammen & Rudolph, 1996) and

is presented ir; Figure 7.4. The case study that was

presemed in 'X J also illustrates the elements of

r

While acknowledging that there are many pathways to depression, Hammen's model places dysfunctional cognitions at the forefront. First, how- ,

ever, the stage for the development of these negative

cognitions is set by family factors, such as a depressed parent, insecure attachment, and insensitive

.or.rejecting caregiving. Adverse interpersonal experiences contribute to the child's development of negative schemata: of the self as unworthy, others as

undependable and uncaring, and relationships as

hurtful or unpredictable. The depressive cognitive

style also involves the belief that others' judgments

provide the basis for one's self-worth, as well as a

tendency to selectively attend to only negative

events and feedback about oneself.

Further, Hammen highlights the fact that the relationships among affect, cognition, and behavior

are dynamic and transactional. For example, negative cognitive styles lead to problems in interpersonal functioning, which act both as vulnerabilities

to depression and as stressors-m-theirown right. The

negative attributions of depressed children interfere

with the development of adequate coping and social

skills, and they respond to interpersonal 'problems

through ineffective strategies such as withdrawal or

acquiescence. These strategies not only fail to resolve interpersonal problems but even exacerbate

,

l

I

I

Chapter 7

-:

Disorders in the Depressive Spectrum and Child and Adolescent Suicide

159

them.:.increasing experiences of victimization, rejecDevelopmental influences also enter into the piction, and isolation. Therefore, the negative cognitive

ture in a number of ways. First, difficulties that ocstyles and poor interpersonal problem-solving skills

cur earlier in development may have particularly

associated with depression further disrupt social

deleterious effects, diverting children to a deviant

relationships, .undermine ihe child's. competence,

pathway from which it is difficult to retrace their

induce stress.rand confirm the child's negative besteps. Once on a deviant trajectory, children become

liefs about the self ana the world.

increasingly less able to make up for failures to deAs development proceeds, these cognitive and in- " velop early stage-salient competencies. Accumuterpersonal vulnerabilities increase the ;elihOOd that

lated stress may also alter the biological processes

individuals will respond with depressio when faced

underlying depression, especially in young chilwith stress during development.Hamme's model dedren, whose systems are not yet fully matured. Secscribes three aspects to the role of stress in depresond, cognitive development can influence depression. First, as described above, individuals vulnerable

sion. As we have seen, young children's thinking

to depression may actually generatesome of their own

tends to be undifferentiated and extreme, constressors. In this way they contribute to the aversivetributing to an "all pr nothing" kind of reasoning.

ness of their social environments, as well as consoliA negative cognitive style formed at an early age,

dating their negative perspectiveson the world. An iltherefore, may be particularly difficult to change

lustration of this kind of process later in development

once consolidated. Third, the organizational view

is "assortative mating," the tendency of individuals to

of development argues that the connections among

choose partners who mirror or act on their vulneracognition, affect, behavior, and contextual factors

strengthen over time. Thus, over the life course, debilities.For example, Hammen and colleagues find

pressivepatterns are integrated into the self system,

that depressed women are more likely than others to

marry men with a diagnosable psychopathology,and,

become increasingly stable, and require lower

in turn, to experience marital problems and divorce

thresholds for activation.

Hammen's model is relatively new, and it is in

which contribute further to their depression.

Second, the association between stress and "dethe nature of research in developmental psypression is mediated by the individual's cognitive

chopathology that decades must pass before we have

data available that fully test a given model by tracstyle and interpretation of the meaning of stressful

events. While life stress increases the likelihood of . ing pathways of development from infancy to adulthood. Therefore, it is too early. to say whether this

psychopathology in general, it is the tendency to in-.

. terpret negative events 'as disconfirmationsof one's

is an accurate account of the developmental psychopathology of depression. To date, parts of the

self-worth that leads to depression in particular:

model have held up to empirical scrutiny. Rudolph,

Third, certain groups of children are at high risk

Hammen, and Burge (1994) demonstrated links bebecause they are exposed to the specific kinds. of

tween child depression and negative cognitions _

stressors that increase depression. These include

about self and other, negative representations of

maltreated children, those whose parents are emotionally disturbed, those in families with high levfamily and peer relationships, biases in social inels of interparental conflict, or those who live in sitformation processing, and poor interpersonal skills.

uations of chronic adversity that diminish the entire

However, in a study of adults, Hammen and eelleagues (1995) found that, while attachment-related

family'S morale and sense of well-being.

negative cognitions and life stress predicted depresBiological factors can comeinto play at any point

in the cycle. For example, individual differences in

sion one year later, the results were not specific to

temperament may contribute to problems' in chilsymptoms of depression. Therefore. it may be that

Hammen's model actually represents a general

dren's relationships with parents and others: Biologmodel for the development of psychopathology, one

ical factors can affect children's ability to cope with

stressful circumstances, as well as increasing their . that can be appliedjo the understanding of depression but is not specific to it.

vulnerability to depression as a reaction to stress.

160

Developmental

Psychopathology

Intervention

PhaJ"acotherapy

CAs noted above, while some studies indicate that ~he

new antidepressants

(SSRIs) reduce depressive

symptoms in children, results are mixed. Undesir-'

able side effects also occur, including restlessness

and irritability, insomnia, gastrointestinal discomfort, mania, and psychoticreactiom'[

(De VanJ &

Sallee, 1996). There are advocates fOr their continued use, who cite the low rates. of serious side effects and the devastating consequences of untreated

depression (Kye & Ryan, 1995). However, others

are strongly opposed, arguing that their use is unethical given that their effectiveness is not supported

by the existing research (Pellegrino, 1996).

Despite questions about the effectiveness of antidepressants with children, JPey are being prescribed at arr increasing rate:fin 1996, U.S. physicians wrote 735,000 prescriptions for SSRIs for

children ages 6 to 18, a rise of 80 percent in only

two years (Clay, 1997). Prozac now comes in peppermint flavor especially designed for children')

As with adult depression, fOJ:child depression the

usual recommendation (if not the usual practice) is

to use antidepressant medic'Jon only as an adjunct

to other forms of treatment.[Many factors thatcontribute to depression-stressful

life circumstances, .

poor parent-child relationships, family conflict and

dissolution, low self-esteem, arid negative cognitive

biases, for example=-cannot

be' changed by psychopharmacologj)and

can be better addressed by.

psychotherapy with .the individual child or the family (Dujovne, Barnard, & Rapoff, 1995).

Psychodynamic Psychotherapy

Psychodynamic

treatments for depression focus.

broadly on problems in underlying personality organizarion, tracing these back to the negative childhood experiences from which depression emerges ',

(The goals of therapy are to decrease.self-criticism

and negative self-representations

and to help the

child to develop more adaptive defense mechanisms

in order to be able to continue on a healthy course

of emotional developmentjwith

younger c~dr~n,

the therapist may use playas a means of bringing

d>.

these issues into the therapy room, with the focus

shifting to d{scussion as children become more cognitively mature (Speier et al., 1995).

Psychodynamic approaches rarely provide outcome studies beyond individual case reports. However, Fonagy an~ Target (1996) investigated the

effectiveness of aldevelop~entally oriented psychoanalytic approach with children. (This is described in

more detail in Chapter 17.) Results showed that the

treatment was effective, particularly for in~malizing

problems such as depression asd anxiety. ounger

children (i.e., under II years) responded

st. However, the treatment was no quick cure; the best results

were found when treatment sessions took place 4 to

5 times per week over a period of two years.

Cognitive Behavior,!l Therapy

An example of a cognitive-behavioral

approach is

the Coping with Depression Course for Adolescence

(Lewinsohn et al., 1996), a downward extension of

a treatment program originally designed for adults.

This intervention includes role playing to teach interpersonal and problem-solving techniques, cognitive restructuring to decrease maladaptive cognitions such

"Nothing ever turns out right for me,"

and self-reinforcement techniqueyStudieS

of the effectiveness. of this approach show that, for the 80

percent of adolescents who improve, treatment gains

are lasting. Cognitive behavioral therapies for child

depression are the most extensively researched, and,

o:,erail, findings concerning their effectiveness are

. very positive (see Marcotte, 1997, and SouthamGerow et aI., 1997, for reviews).

as

Family Therapy

A comprehensive review by Dujovne, Barnard, &

Rapoff (1995) examines the relative effectiveness

of a number of different treatments for childhood

depression.

They conclude that rc~IY-fOcuSed

.. treatments (family therapies) .warrant pnmary consideration, given the roles of the family sitwition.

parent-child

relationships,

and parent depression in

. the developm~nt of.de?ress~ve sp~c~m disorders.

Consistent With this, \Lewmsohn s group (1996)

found that the effectiveness of their cognitivebehavioral intervention for depressed children was

enhanced by the addition of interventions with the

II-

Chapter 7

Disorders in tDe Depressive Spectrum and Child and Adolescent Suioce

infant'S attention, thus increasing the level of muparents. Group sessions are held in which parents

tual interest and engagement. Results suggest that

are given the opportunity to discuss issues related

each specific coaching strategy improved the interto depression and to .learn the same infrpersonal

actional behavior of the type of depressed mother

communication and conflict resolution skills being

taught to their children.]

.

for whom .it ~.as de~elopey

Arr effective multifaceted approach to treating

_

J

,

child depression in the family c9ntext is described

Child and Adolescent Suicide

by Stark and associates (l996).l{nterventions with

the child include the use of individual and group

therapy in order to increase positive mood and exDefinitions and pretalence

pectations, restructure maladaptive schemata, and

cbs we begin our discussion of suicide, we must im- enhance social skills. Interventions aimed at the

mediatelydistinguish among three categories: suicilarger system include parent training and family

therapy in order to reduce the environmental stresses.

dalthoughts, suicide attempts, and completed suicide.

that contribute to the development of depression. _JOur review' follo~ ~~land and Zigler, 1993, ~x~ _.

Further, consultation with teachers is provided to

cept where noted.) SUlczdal thoughts,~nce considered-to be rare in childhood, are in fact disconcertpromote and reinforce children's use of adaptive

ingly prevalent. Studies of U.S. high school students

coping strategies during the school

have found that 63 percent experienced suicidal

. Prevention"

thoughts, while 54 percent of college students had

c~nsidered suicide at least once in their Iives)

~ Efforts to prevent the development of childhood de(!)Suicide atte.0lZEGpicaily involve using a slowpression have focused on those most at riskacting method under circumstances in which disnamely, children of depressed mothers. For examcovery is possible. The act is most often in reacple, Gelfand and colleagues (1996) developed an intion to an interpersonal conflict or significanttervention program for depressed mothers and their

stressor. Although the attempt 'is unsuccessfu9 it:-'

infants. Home visits were made by trained nurses

may nevertheless be serialS, serving as "practice"

whose goals were to increase depressed mothers'

parenting efficacy as well as,to foster more positive

for a futur.elethal attempt~pproxirnately, 7.per~ent . _

mother-infant interactions)Mothers who particiof U,S. high school students. attempt SUICIdeIn a

pated improved in reported depression and per- . given year (Centers for Disease: Control, 1995), and

there are reports of repeated and apparently serious~'~'

ceived stress, and both their own arid their infants'

attempts at suicide ~ng

preschopler~Rosenthal

overall adjustment improved. Children of mothers

who participated were also less avoidant in their at& Rosenthal, I984).(further, while as many as 10

percent of college students report having made a

tachment than other children; however, they were

alsp more resistant.

.

suicide attempt, only 2 percent of those had sought

medical or psychological help)Therefore, our sta(An intriguing study by Malphurs and colleagues

tistics on the prevalence of suicide attempts may be

(1996) targeted another at-risk sample, depressed

underestimates.

teenage mothers. Mothers were observed interact(j)Coppleted suicide, while, rare,is a significant

ing with their infants and were differentiated in

problem among adole~uicide

is the third

terms of whether they demonstrated a withdrawn or

leading cause of death among 15- to 19-year~old

an intrusive parenting style. Specific types of interadolescents in the United States, in line behind acventions were designed t-;;tieIp counter these probcidents and hornicidesl (Garland & Zigler, 1993).

lematic patterns) For example, intrusive mothers

were coached ~ imitate their children's behavior, (Further, suicide among the young is increasing at an. 'IV' cQ.S

alarming rate, with rates rising much more dramatthus giving children more opportunities to initiate

ically than in the general populationjwhile suicide

and influence the flow of the interaction. In conin the general population has increased 17 percent

trast, withdrawn mothers were coached to keep their

daY;)

';

r .

161

d.

[)eolejelplTlenta

162

sychopa ology

20

18

16

5uidde rate per

100,000 in pop~

14

. 12.

10

8

6

4

2

O~-r----r----.----r----.----~---.----.----.----'-1960--62 63-65

Figure

7.5

Source: Garland

66-68

69-71

72-74

75--77 71h'10. 8,.,83

-e-

White males

-0-

NonWhite males

___

WhIte females

-{}-

Nonwhite females

84--86. 87-M

U.S. Youth Suicide Rates for 1S- to 19-Year-Olds by Race and Gender.

and Zigler. 1993

since the 1960s, among adolescents it has increased

200 percent, to 11.3 per 100,000. (See Figure 7.5.)

Rates for younger children are lower: In 1991, the

suicide rate for .children aged 5 to 14 was 0.5 per

100,000. A protective factor for younger children

may be that they have.more, ..difficulty. accessing

lethal means; consequently, there are 14.4 attempts

for every completed suicide in'lO- to ll-year-olds

(Pfeffer et al., 1994). Most suicides (70 percent) OCcur in the horne. Firearms are the most frequent

method used b~ both males and females (59 per-.

cent), followed by hanging for males and drug ingestion for females.

tIn all age groups, females are more likely than

males to attempt suicide, while males are more likely

to succeed. Females attempt suicide at least three

times as often as males do, whereas males ~omp1ete

suicide about four times as often as females) The ex- .

planation for this appears to lie in the choice of

method. In contrast to male suicides, two-thirds of

whom die by self-inflicted gunshot wounds;the typical young female attempter ingests drugs at home.

The latter case is called low-lethality behavior because of the length of time needed for the method to

take effect and the likelihood that someone will find

the attempter before it is too late to resuscitate. It

should not be assumed, however, that young womenr

are less serious about wanting to die. Females are

more likely to have an aversion to violent methods,

and sometimes young people's understanding of

how deadly a drug can be is simply inaccurate. Further, these statistics often come from mental health

clinics and ignore one very important group incar.~

.males.lf W~ illcl.I.Ided...waks In.juvaUk

detention facilities in these statistics, the gender

differences in suicide attempts might not be so great.

Etiology

The Intrapetsonal Context

Psychological characteristics distinguish some adolescent suicides, the majority of whom have a diagnosable psychopathology (Beautrais, Joyce, &

Mulder, 1996). For example,(83 percent of youths

with suicidal ideation show signs of depression. The

.relationship between sllifide and depression is a significant but complex onf. Most depressed youths are

.:not suicidal. Further, while Harrington 'and co1leagues' (1994) longitudinal research

that

_childhood -depression is a strong predictor. of attempted suicide in adulthood, the key seems to be

the association between childhood depression and

adult depression. In other words, depressed children

who grow up to be nondepressed adults are not at

risk for suicide.

s~s

i -

I

I

Chapter

Disorders-in the Depressive Spectrum

and Child and Adolescent

Suicide

163

There are other significant predictors of youth

The link between conduct disorder and suicide may

suicide besides depression. Clues to these can be

also be strongest for boys, with the combination of

found in a study of 3,000 suicidal youths attending

depression and conduct problems particularly toxic.

a free medical clinic (Ado links, 1987). Feeling (f Capaldi (l9?2)

found that, among boys who

states preceding theirsuicide

attempts were anger

showed a combination of depression and aggresfirst, followed by loneliness, worry about the future,

sion, school failure, poor relationships with parents

remorse orsharne,

and hopelessness. The reasons

and peers, and low self-esteem resulted in suicidal

youths gave for attempting suicide were; ill order,

ideation two years later)

However, it is important to recognize that suicirelief from an intolerable state of mind or escape )

from. an impossible situation, making people undal adolescents are a diverse group. Some may exderstand how desperate they feel, making someone

hibit no apparent problems or disorders. They may

appear to be "model" youth who keep their anxiety,

sorry or getting back at someone, trying to influence someone or change someone's mind, showing

perfectionism, and feelings of failure to themselves.

how much they loved someone or finding out

The Interpersonal Context:

whether someone really loved them, and seeking

Family

Influences

help. Many had been preoccupied with thoughts of

The family context is also important, although a sigdeath for an extended period of time, but only

nificant weakness of many family studies is that they

around half of the adolescents said they actually

wanted the attempt to succeed. Typically, despite the

are retrospective rather than prospective, (Here we

long, gestation period of suicidal thoughts, the acfollow the review by Wagner, 1997. unless otherwise noted.) Assessing suicide only after it is attual attempt was made with little-premeditation.

tempted does not provide convincing evidence that .

These data have two important implications.

First, impulsivity is implicated in suicide. Impulfamily-factors lead up to suicide.

sivity may be seen in many ways, including low

A number of studies have confirmed the exis- .:

tence of a significant degree of family dysfunction

frustration tolerance and lack of planning, poor

self-control, disciplinary problems, poor academic

and adverse childhood experiences among suicide

performance, and risk-taking behavior. Substance

attempters) (Beautrais, Joyce, & Mulder, 1996).

Prospective studies show that suicidal ideation and

abuse is found in 15 to 33 percent of suicide compIeters, with suicidal thoughts increasing after the

suicide attempts are predicted by low levels of paronset of substance use. Substance abuse may play"

ent warmth, communicativeness,

support, and emoa: role in increasing impulsivity, clouding judgment,

tional responsiveness. and high levels of violence,

vand disinhibiting self-destructive behavior. Other

disapproval, harsh discipline; abuse, and general

family conflict. Retrospective studies show that atdisorders of impulse control. including eating distempters and their parents describe the family as

orders, are also related to an increased risk for suihaving lower cohesion, less support. and poorer

cide (Berman & Jobes, 1991).

adaptability to change. Suicide attempters also are

Secondly, ~nger and aggression emerge as an

more likely to report feeling that they are unwanted ..

important part of the suicide constellation) About

.70 percent of suicidal youth exhibit conduct.disoror burdensome to their families. There is a signifi.rler and antisocial

behavior (Berman & Jobes,

cantly high level of psychopathology 'among family

1991). Childhood conduct disorder also has been'

members, particularly suicide and depression.

Perceived lack of support from parents also has

shown to predict adult suicidality independently of

depression (Harrington et al., 1994). Achenbach

been implicated as a significant predictor of adolescent suicidal thinking (Harter & Marold, 1994).

and colleagues' (1995b) six-year longitudinal study

Further, Harter and Whitesell (1996) found that

also shows that suicidal ideation is predicted, not

the depressed youths exhibiting the least suicidal .

by depression, but by earlier signs of externalizing

ideation were those who perceived themselves to

disorders: for boys, intbe.form

of aggressiveness,

and for girls, in the form. of delinquent behavior.

have more positive relationships" with parents and

164

Developmental

Psychopathology

more parent support. Thus supportive parent-child

relationships IDf-yprovide a buffer against suicidality in at-risk children.

.

Finally, exposure to the suicidal behavior of

another person in the family or immediate social

network is more 'Common in suicidal adolescents

than in controls. This has been referred to as a contagion effect: Children who are exposed to suicidal

behavior, especially in family members or peers,

are more likely to attempt it themselves. Such exposure should be regarded as accelerating the risk

factors already present rather than being a sufficient

cause of suicide.

The Interpersonal Context:

Peer Relations

Perceived (Jackof peer supportJ(HfI1er & Marold,

1994) and~or social adjustmenj (Pfeffer et al.,

1994) have been identified as risk factors. Suicidal

youth are more likely than others to feel ignored

and rejected by peers. They also report having

fewer friends and are concerned that their friendships are contingent-that they must behave a certain way in order to be accepted by agemates. Perceived social failures, rejection, humiliation.' and

romantic disappointments

are common precipitants of youth suicide.

The Superordinate Context

Socioeconomic disadvantage has also been associated with suicide (Beautrais, Joyce, & Mulder, 1996),

with children growing up in poverty being at greater

risk for suicidal fu.oqghts, attemp~, and completi~ns.

~~"( ..s~U~

""'1

trt

~~

"'.t)"",,-~

~~\

.s~~~

'> ~

showing that childhood suicide attempts are a strong

predictor of spbsequent attempts and completions.

For example, \';ix to eight years after their first attempt, suicidal children were six times more likely

than other children to have made another suicide

_attempY:Pfeffer

et,al:, 1994). Most subse~~~nt attempts occurred Within two years of the initial a~- .

tempt, and over half of those who continued to be

4uicidal made multiple attempts. Therefore, suicide

attempts in children should not be dismissed as mere

attention-getting behavior, since those who engage

in them are at risk for more serious attempts and

possible completions in the future.

Among(adolescent

suicide atternpters, Adolinks

(1987) found that the majority improved within one

month. However, about one-third subsequently experienced major difficulties in the form of increased

psychological and physical disorders, interpersonal

problems, and increased criminal behavior. One in

ten repeated the attempt, with boys succeeding more ;

often than girls, The risk for future disturbances was

particularly strong ill teenage males)

Integrative Developmental Models

A classic reconstructive account is provided by Jacobs (1971), who investigated fifty 14~ to 16-yearolds who attempted suicide: A control sample of

thirty-one subjects, matched for age, race, sex, and

level of mother's education was obtained from a 10- '

cal high schooL Through an intensive, multi-technique investigation, Jacobs was able to reconstruct

a five-step model of the factors leading up to suicidal attempts:

Developmental Course

1. Long-standing history of problems from early

childhood. Such problems included parental di- .

The question often arises as to whether youn/children who attempt suicide are really trying to. kill

themselves, and therefore whether their attempts

warrant serious concern or presage future suicidal- .

ifY:Doubt about whether they really intend to die is

supported by cognitive-developmental

research on

children's limited understanding of the concept of

death, as weU as studies showing that suicidal children have a .limited understanding of the permanency of death (Cuddy-Casey & Orvaschel, 1997).

However, ~ngitudinal

research is consistent in

vorce, death of a family member, serious illness,

parental alcoholism. and school failure, Subsequent research has shown that it is ahigb level

- of intrafamilial conflict along with a lack of support for the child that is the riskfactor, not a par, . ticular family consteUation such

divorce or

single parenthood (Weiner, 1992).

2. Acceleration of problems in adolescence. Far

more important than earlier childhood problems

was the frequency of distressing events occur;

ring within the last five years for the suicidal

c.' .. '

as

Chapter 7

Disorders in the Depressive Spectrum

youths; for example, 45 percent had dealt with divorce in the previous five years as compared

to only 6 percent of the control group. Terrni-\

nation of a serious romance was also much

- higher among the suicidal group, as were arrests

and jail sentences.

3. Progressive failure to cope and isolation from

meaningful social relationships. The suicidal and

control groups were equally rebellious in terms

of becoming disobedient, sassy, and defiant.

However, the coping strategies of suicidal adolescents were characterized much more by withdrawal behavior, such as avoiding others and engaging in long periods of silence (see also Spirito

et al., 1996). The isolation in regard to parents

was particularly striking. For example, while 70

percent of all suicide attempts took place in the

home, only 20 percent of those who reported the

attempt had informed their parents about it. In

one instance an adolescent telephoned a friend

who lived miles away, and he, in turn, telephoned

the parents who were in the next room.

4. Dissolution of social relationships. In the days

and weeks preceding ~e attempt, suicidal adolescents experienced th~rea1cing off of social relationships, leading to the feeling of hopelessness.

5. Justification of the suicidal act, giving the adolescent permission to make the q,ttempt.This justification was reconstructed from 112 suicide

notes of adolescents and adults attempting and

completing suicide. The notes contain certain recurring themes; for example, the problems are

seen as long-standing and unsolvable, so death

seems like the only solution. The authors of such

notes also state that they know-what they are doing, are sorry for their act, and beg indulgence.

The motif of isolation and subsequent hopelessness is prevalent.

r_

Another comprehensive account of the development of suicidal ideation is offered b1Earter (Harter, Marold, & Whitesell, 1992; Harteree Marold,

1991, 1994), who integrates her own research with

that of others. Her model reconstructs the successive steps that ultimately eventuate in suicidal

ideation in a nonnative sample of 12- to IS-yearolds. (See Figure 7.6.)

and Child and Adolescent

Suicide

165

Immediately preceding and highly related to suicidal ideation is what Harter calls the depression

composite, which is made up of three interrelated

variables: low global self-worth, negative affect, and

hopelessness. The first two are highly correlatedthe lower the perceived self-worth, the greater the

feelings of negative mocd,

_ J ,

Moreover, the depressive composite is rooted

both in the adolescents' feelings of incompetence

and in their lack of support froln family and

friends. These two variables of. competence and

support are, in turn, related in a special way. In

regard to competence, physical appearance, peer

likability, and athletic ability are related to peer

support, while scholarly achievement and behavioral conduct are related to parental support. Finally, adolescents identify more strongly with

peer-related competencies, with the others being

regarded as more important to parents than to

themselves.

Analyses of the data revealed that peer-related

competencies and support were more strongly

related to the depressive composite than were

parental-related competencies and support, perhaps because the former are more closely connected with the adolescents' own self-concept.

However, parental support was important in differentiating the adolescents who were only depressed from those who were depressed and had

suicidal ideation. Further, the quality of support

was crucial, Regardless of the level, if adolescents

perceived they were acting only to please parents

or peers, their self-esteem decreased and depression and. hopelessness increased. On the other.

hand, uncoriditional support helped adolescents

minimize the depressive composite.

In regard to the question of which came first, lowered self-worth or depression, the data indicate that

causation can go in either direction. Some adolescents

become depressed when they experience .lowered

self-worth, while others become depressed over other

occurrences such as rejection or conflict, which in

turn lower self-worth.

To answer the question, Why adolescence? Harter and colleagues (1997) marshal a number of findings concerning this period. IIi adolescence, selfawareness, self-consciousness, intiospection, and

166

Developmental

Psychopathology

Competence/Adequacy

plus

~opefrn,!ess (If Important) fon

PIiYSl~~P~~RAN(_E.

PEER LlKfJ'.BIUTY

" c'

1

ATHLETIC CdMPETENCE :.

Levelof plus

Hopelessness about;

D.epresslon Composite:

."7'

P~ER SUP.PORT

-Level cif plus' .

:'~~I.e~sness

:."

SEu:--WORTH

AFFECT

,GENERAL HOPELESSNES.S

SUIOOAl

. loiAffON -

about

PARENT SUPP.ORT

-t:ompe&lielMequ~cY plus

-Ho~ele'mie~ (If Important) for:

~~~~i'&;~p~c~

-liEHAVIOlto\L.CONDUq,

~.~- .... ~~;; :.:.;:' ~

-,:

Figure

7.6

Risk Factors for Adolescent Suicidal Ideation.

Source: Harter. Marold. and Whitesell,

1992

preoccupation with self-image increase dramatically,

while self-esteem becomes more vulnerable. Peer

support becomes significantly more salient, although

adolescents still struggle to remain connected with

parents. For the first time, the adolescent can grasp

the full cognitive meaning of hopelessness, while affectively there is an increase in depressive symptomatology. Suicidal ideation is viewed as an effort to

cope with or escape from the painful cognitions and

affects of the depressive. composite.

Intervention

frhe vast majority of suicidal adolescents provide

clues as to their imminent behavior; one study found

that 83 percent of completers told others of their suicidal intentions in the week prior to their death. (Our

presentation

follows Berman and Jobes, 1991.)

Most of the time such threats are made to family

members or friends, who do not take them seriously,

try to deny them, or do not understand their irnpprtance. Friends, for example, might regard reporting

the threats as a betrayal of trust. Thus, not only do'

adolescents themselves not seek professional help,

but those in whom they confide tend to delay or re. sist getting help. Consequently, an important goal

of prevention is to educate parents and peers concerning risk signs.

Once an adolescent comes for professional help,

'the immediate therapeutic-task is to protect the youth

from self-harm through crisis intervention. This

might involve restricting access to the means of commitring suicide, such as removing a gun from the

house or pills from the medicine cabinet; a "no sui- -.

cide contract" in which the adolescent agrees not to

hurt himself or herself for an explicit time-limited

period; decreasing isolation by hav[;gsympathetic

family members or friends with the adolescent at all

timeszgiving medication to reduce agitation or de- .

pression; or, in extreme cases, hospitalization.

.'

Chapter

Disorders in the Depressive Spectrum

Suicide Prevention

Turning again to Garland and Zigler's (1993) review, we find that two of the most commonly used

suicide prevention efforts-suicide hot lines and

media campaigns=-are only minimally effective.

Communities with suicide hot lines have slightly re- duced suicide rates; however, hot lines tend to be

utilized by only one segment of the population, Cau- .

casian females. Even less helpful, well-meaning eftorts to call media attention to the problem of suicide among teenagers may have the reverse effect.

Several studies have shown increased suicide rates

following television or newspaper coverage of suicide, particularly among teenagers.

School-based suicide prevention programs are

extremely popular, with the number of schools implementing them increasing 200 percent in recent -,

years. Goals of these programs are to raise awareness of the problem of adolescent suicide, train participants to identify those at risk, and educate youth

about community resources .available to thern.:

However, a number of problems have been identified with school-based suicide prevention efforts.

For one thing, they may never reach the populations most at risk because incarcerated youths, runaways, and school dropouts will never attend the

classes. Even when students do attend the pro.grains, there are questions as to their-benefits. The

programs tend to exaggerate the prevalence of

teenage suicide, while. at the same time de-ernphasizing the fact that most adolescents who attempt

suicide are emotionally disturbed. Thus, they ignore

evidence for th"e contagion effect and encourage

youth to identify with the case studies presented.

By trying not to stigmatize suicide. these programs

may inadvertently normalize suicidal behavior and

reduce social taboos against it.

and Child and Adolescent

Suicide

Large-scale, well-controlled studies provide some

basis for these concerns. For example. one study of

300 teenagers showed that attending a suicide prevention program slightly increased knowledge

about suicide but was not effective in changing attitudes about it. Boys in particular tended to change .. -in the undesirable-direction: more of them reported

increased hopelessness and maladaptive coping after expc\sure to the suicide program (Overholser et

al., 198;). Another study of 1,000 youths found no

positive effects on.attitudes toward suicide. In fact,

participation in the program was associated with a

small number of students responding that they now .

thought suicide was a plausible solution to their

problems. The students most at risk for suicide to

begin with (those who had made previous attempts)

were the most likely to find the program distressing (Shaffer et al., 1991).

If suicide prevention programs are not the solution,

what mightbe? While suicide is rare, Garland and

Zigler (1993) point out, the stressors and life problems that may lead some youth to it are not. Therefore, successful prevention programs might be aimed

toward such risk factors for suicide as substance abuse,

impulsive behavior, depression, lack of social support,

family discord, poor interpersonal problem-solving

skills, social isolation, and low self-esteem.

Recall that in Chapter 5 we dealt with the issue of

control in the toddler-preschool period--control of

excessive negativism and control of the bodily functions of eating and urination. We will now return to

this theme of control, exploring its manifestation in:

the middle childhood period. We will examine two

extremes: excessive control, which is an important element in anxiety disorders, and inadequate self-control, which lies at the heart of conduct disorders.

167

..

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Class 13 - TreatmentDocumento18 pagineClass 13 - TreatmentDaniela Pérez MartínezNessuna valutazione finora

- Nccaom Biomed Exam ContentDocumento12 pagineNccaom Biomed Exam Contentapi-251021152Nessuna valutazione finora

- IJM Safety Conference Paper Summarizes NADOPOD 2004 Reporting RegulationsDocumento1 paginaIJM Safety Conference Paper Summarizes NADOPOD 2004 Reporting RegulationsKay AayNessuna valutazione finora

- Stress Reduction ActivityDocumento4 pagineStress Reduction ActivityBramwel Muse (Gazgan bram)Nessuna valutazione finora

- Nature's Role in Reducing Mental FatigueDocumento9 pagineNature's Role in Reducing Mental FatigueCrăciun RalucaNessuna valutazione finora

- Gabriela QuinteroDocumento1 paginaGabriela Quinteroapi-490976036Nessuna valutazione finora

- Autoimmune Encephalitis Syndromes With Antibodies - UpToDateDocumento1 paginaAutoimmune Encephalitis Syndromes With Antibodies - UpToDateSamNessuna valutazione finora

- Dr. Imam Khoirul Fajri's Medical Career and AccomplishmentsDocumento5 pagineDr. Imam Khoirul Fajri's Medical Career and AccomplishmentsDokter ImamNessuna valutazione finora

- Deep Pressure Proprioceptive ProtocolsDocumento6 pagineDeep Pressure Proprioceptive Protocolsnss100% (1)

- Health Grade 5 Ontario PDFDocumento2 pagineHealth Grade 5 Ontario PDFFrances & Andy KohNessuna valutazione finora

- Mock5 PDFDocumento19 pagineMock5 PDFSpacetoon Days100% (1)

- Myanmar HealthcareDocumento8 pagineMyanmar Healthcarezawminn2Nessuna valutazione finora

- Exam Anxiety in School Students: Muskan Agarwal 1-B Enroll No.-A1506920362 Faculty Guide - Dr. Anika MaganDocumento16 pagineExam Anxiety in School Students: Muskan Agarwal 1-B Enroll No.-A1506920362 Faculty Guide - Dr. Anika MaganMuskan AgarwalNessuna valutazione finora

- 1994 Institute of Medicine Report, "The Use of The Heimlich Maneuver in Near Drowning"Documento30 pagine1994 Institute of Medicine Report, "The Use of The Heimlich Maneuver in Near Drowning"Peter M. HeimlichNessuna valutazione finora

- Joyce Travelbee's Human-to-Human Relationship ModelDocumento4 pagineJoyce Travelbee's Human-to-Human Relationship ModelHugMoco Moco Locah ÜNessuna valutazione finora

- Materi 1 LUTS Bedah Dasar EDIT FIXDocumento20 pagineMateri 1 LUTS Bedah Dasar EDIT FIXfienda feraniNessuna valutazione finora

- Iris Cheng Cover LetterDocumento1 paginaIris Cheng Cover Letterapi-490669340Nessuna valutazione finora

- Daily Lesson Log on Lifestyle and Weight ManagementDocumento8 pagineDaily Lesson Log on Lifestyle and Weight ManagementNoel Isaac Maximo100% (2)

- SHS Applied - Inquiries, Investigations and Immersions CG - Spideylab - Com - 2017Documento4 pagineSHS Applied - Inquiries, Investigations and Immersions CG - Spideylab - Com - 2017Lexis Anne BernabeNessuna valutazione finora

- سندDocumento82 pagineسندAshkan AbbasiNessuna valutazione finora

- Medical AnthropologyDocumento5 pagineMedical AnthropologyAnanya ShresthaNessuna valutazione finora

- The CHIPS Randomized Controlled Trial (Control of Hypertension in Pregnancy Study)Documento7 pagineThe CHIPS Randomized Controlled Trial (Control of Hypertension in Pregnancy Study)Stephen AlexanderNessuna valutazione finora

- PPIs and Kidney DiseaseDocumento6 paginePPIs and Kidney DiseaseSonia jolandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Magnesium Chloride Walter LastDocumento8 pagineMagnesium Chloride Walter Lastapi-3699819100% (6)

- BFCI Annexes 1Documento60 pagineBFCI Annexes 1BrianBeauttahNessuna valutazione finora

- UB04 Instruction GuideDocumento14 pagineUB04 Instruction GuideDragana100% (1)

- WHO IVB 12.10 EngDocumento36 pagineWHO IVB 12.10 EngJjNessuna valutazione finora

- K4y Final EvaluationDocumento9 pagineK4y Final Evaluationapi-3153554060% (1)

- Informational InterviewDocumento3 pagineInformational InterviewMelissa LinkNessuna valutazione finora

- Abstrak Dr. Idea MalikDocumento2 pagineAbstrak Dr. Idea MalikAndrio GultomNessuna valutazione finora