Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Canadian English

Caricato da

Elise DalliCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Canadian English

Caricato da

Elise DalliCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Canadian English Phonology

So, lets talk about the phonology! First off, I want to start with a few basic

points:

Canadian English and Standard American are actually really similar; as

Clair said, Canada leans towards the Standard America dialect so, for

instance, Canadian English is considered a rhotic language because the

syllable-final r is pronounced in words like car and farm in most of the

Canadian states, just like in America. Ive actually read an interesting

theory about this in a journal published by the Queens University in

Ontario that states that the English spoken in Canada and America the

rhotic languages, in other words pronounced the r because they were

colonized far earlier than the southern hemisphere colonies. Between

colonizing North America and colonizing, for example, Australia, New

Zealand and South Africa, the English spoken in Britain underwent a huge

change like dropping the pronunciation of the r final-syllable, for

example. The table you can see here let me make it a little bigger so its

clearer is the Canadian variation of John Wells lexical sets; as you can

see, theyre a set of 24 words that are used, in phonology, to analyse

different accents in the English language. Wells chose them specifically for

their clarity its impossible to mistake them for any other words.

Now, pre-rhotic vowels such as the o in the words sorry and borrow

are a unique feature of Canadian English pronunciation. In American

pronunciation, there is a tendency to replace the o in a word with an

inter-vocalic r with an a so, sorry, tomorrow, borrow, sorrow, are all

said with an a rather than an o. In Canada, however, the [o] is

maintained before the intervocalic [r]. So whereas an American would say

sari and baro, the Canadian pronounciation is actually sori and boro.

Despite retaining the o before r, Canadian English has, however, lost the

distinction between [ae] (ah) and e (e) when they occur before an intervocalic r Howard Woods, in a study of Ottawa residents, found that this

was primarily older speakers, who tended to pronounce marry as maeri.

The only state that does not actually pronounce the r is Nova Scotia, one

of the Atlantic Provinces.

Intervocalic T

The t is voiced intervocalically -- When voicing a t after a stressed

syllable, usually it becomes pronounced as a d for example, city

becomes sidi; little is lidel, like the shop, and it is one of the most distinct

structures of Canadian English. According to Chambers 1993 report,

Lawless and Vulgar Innovations, this dated back to Victorian views of the

Canadian dialect which were, on the whole, not very favourable.

Merger of Low-Back vowels

The merger of low back vowels low back vowels are the vowels you

produce by dropping the jaw down to a low position. In Canadian English,

the low-back vowels

(oh) and

(aw) are pronounced entirely alike;

the distinction between them in British English doesnt get translated into

Canadian English. For instance, cot

and caught

are both

pronounced as cot.

This is also known as the Canadian shift.

Similar to this is the disappearance of vowel contrast in words which use

the same letters so, for example, logger and lager both sound like they

have the same vowel (trudgill and Hannah, 1982). However, the

Canadian Shift does not occur in all of Canada the Atlantic Provinces

(New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia and Newfoundland)

[ In a nation-wide survey (over 14000) Canadians, Scargill and

Warkentyne reported that an average of 85% of Canadians

responded yes when asked if cot and caught rhyme. In

Newfoundland, the rate dropped to 60%. ]

In foreign words, Canadians almost exclusively use the /ae/ pattern,

whereas in British English, words such as falafel, karate, llama, and so on,

can either have an /ae/ sound or /a:/, depending on where the stress of the

word falls. So, whereas in British English, pasta would be prounced with an

/ae/ whereas llama would be pronounced with an /a:/, in Canadian English

the two are both pronounced in the same way. The only exception occurs

in words with final stressed open syllables, such as foie gras, spa, where

the /ae/ sound cannot appear.

Canadian Raising

Canadian Raising is the chief unique feature in Canadian English, and that

is the pronunciation of diphthongs. Diphthongs are a two different vowel

sounds combined in such a way that they only seem like one such as ou

in house, the oy of boy, and the ie of died. Canadians actually

pronounce both diphthongs, rather than one, by pushing the first part of

the dipthong to the centre of the word and making it a far more noticeable

feature. This mostly happens when the vowels are followed by a voiceless

consonant such as p, b, t, k, and so on, though it doesnt mean that a

voiced consonant will not lead to pushing the vowels up. In RP, when

saying house, the ou of house is longer and lower than the Canadian

variant, which not only lifts the vowels to the mid-range, but also shortens

the glide between one and the other.

o Based on the Great Vowel shift that happened in the 15 th and 16th

century when English shifted from Middle English to Modern English

though nobody quite knows where Canadian English came from.

One unique word pronunciation is khaki. Khaki, an Indian word meaning

dust, is pronounced completely differently from the British and American

versions. Whereas the British draw out the a, thus kaahki, and the

Americans create a diphthong in the middle, khaki (keeki), Canadians add

an r after the a to make karki similar to car key. This is probably due to

the Canadians growing accustomed to the british dropping the r before a

consonant.

Several other examples of phonemic differences:

o Theres also the pronunciation of the letter z as zed similar to

England. In fact, in an article by Bill Casselman, he points out the

incredulity of an American customer attacking a Canadian waitress

for using the word zed instead of zee, claiming that the form zed

is actually the authentic pronunciation of zed he also points out

that more and more Canadians are pronouncing z as zed instead

of zee.

o Words of French origin are pronounced as though they are in french

so, clique would be clique, and not clique [click];

o Sometimes, the I vowel in words such as milk and lick is

pronounced as an e so, to certain speakers, a Canadian saying

milk would actually sound as though he is saying melk.

o In words ending with ile, all letters are pronounced for example,

instead of saying fertil, Canadians say fer-tile.

o In the case of words such as shone, lever and schedule, Canadians

go with the British pronunciation so, shone [gone], leever and

xedule.

Conclusion

To conclude our presentation, Canada is the second largest nation in the world,

populated by 29 million people. It was discovered by the French, who named it

Acadia, and it was given to the British after the Treaty of Ultrecht resolved Queen

Annes war, part of the French and Indian wars fought between the French and

the British. The French were deported and British, Irish and Scottish immigrants

took their place. It is this diverse background of immigration that led to Canadian

English.

Although most of the phonology, phonetic, lexis and other qualities mimic North

America, there are a few differences between Canadian English and Standard

American this is also not taking into account the Maritime provinces, whose

influence seems to be more Scottish based than American. These differences

make Canadian English the noticeable variety of English that as it is spoken to

day: the low-back vowel merger, where the vowels are pronounced by dropping

the jaw to a lower position, the various rules governing the pronounciation of prerhotic symbols, and Canadian Raising, where the diphthongs of a word are

raised to a mid-vowel, resulting in words such as hoose and aboot.

With regards to spelling and pronunciation, they lean more towards the British

variants than the American versions, and they have retained some native place

names and the names of flora and fauna indigenous to the area suc as

Pugwash, Ottawa, tobacco, potato, caribou. However, Quebecian English is

different from standard Canadian English by borrowing a great deal from French;

in Canada, Quebec is a predominantly French-speaking state, and this may

account for it.

Their syntax is quite unique. Among others, Canadian English uses a great deal

of the after and the past participle as Michaela said, they like to say Im after

doing the dishes, and to use anymore as an ending to a positive sentence.

They also over-exclaim a fact, using ever. Furthermore, the usage of the word

eh parodied on many, many, many shows is used to end a questioning

sentence. Another unique feature is the extension of the past perfect (shes been

six years dead) and the do + be negative I get that, but I dont be out of

breath.

I hope you enjoyed our presentation on Canadian English. Thank you.

http://www3.telus.net/linguisticsissues/britishcanadianamericanvocabcanadianpr

on.html

http://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1314&context=pwpl

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/North_American_English_regional_phonology#Canadi

an_English

http://icmigration.webhost.uits.arizona.edu/icfiles/ic/lsp/site/Canadian/canphon3.html

http://www.yorku.ca/twainweb/troberts/raising.html

http://books.google.com.mt/books?

id=jQAMu3QcqzcC&printsec=frontcover#v=snippet&q=canada&f=false

http://www.academia.edu/4001676/Varieties_of_English_Canadian_English_in_real

-time_perspective

http://www.queensu.ca/strathy/apps/OP6v2.pdf

http://ling.upenn.edu/phono_atlas/Atlas_chapters/Ch11_2nd.rev.pdf

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canadian_Shift#cite_note-Labov-6

http://ling.upenn.edu/phono_atlas/Atlas_chapters/Ch15_2nd.rev.pdf

[links for pronounciation videos:

http://icmigration.webhost.uits.arizona.edu/icfiles/ic/lsp/site/Canadian/canphon3.html#di

phthongs

http://www.yorku.ca/twainweb/troberts/raising.html

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Maltese History NotesDocumento18 pagineMaltese History NotesElise Dalli100% (2)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- Dialogue Presentation RubricDocumento1 paginaDialogue Presentation RubricJhay Mhar A100% (7)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Introduction To The Comparative Grammar of The Semitic LanguagesDocumento97 pagineIntroduction To The Comparative Grammar of The Semitic Languagessicarri100% (5)

- Chapter 10 11 - TompkinDocumento3 pagineChapter 10 11 - Tompkinapi-393055116Nessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 1ID Practice Ws - ExamDocumento6 pagineUnit 1ID Practice Ws - ExamJunior Vasquez Palacios100% (1)

- PYP4 Welcome Letter PDFDocumento4 paginePYP4 Welcome Letter PDFAlaa Mohamed ElsayedNessuna valutazione finora

- Change in Frequency DuringDocumento7 pagineChange in Frequency DuringElise DalliNessuna valutazione finora

- Chrome Tanned Leather Conservation: Ducted by Prof. F. L. Knapp, A German Chemist Who in The I 85o's DemonstrateDocumento5 pagineChrome Tanned Leather Conservation: Ducted by Prof. F. L. Knapp, A German Chemist Who in The I 85o's DemonstrateElise DalliNessuna valutazione finora

- Notes On StructuralismDocumento3 pagineNotes On StructuralismElise Dalli100% (1)

- History NotesDocumento82 pagineHistory NotesElise DalliNessuna valutazione finora

- North Berwick Witch TrialsDocumento9 pagineNorth Berwick Witch TrialsElise DalliNessuna valutazione finora

- Dissertation Notes: Part One: Unit OperationsDocumento13 pagineDissertation Notes: Part One: Unit OperationsElise DalliNessuna valutazione finora

- Learning Plan Stage 1 and 2: Grade Level StandardsDocumento5 pagineLearning Plan Stage 1 and 2: Grade Level StandardsBeverly Joy RenotasNessuna valutazione finora

- Thai Alphabet Made Easy #2 Ngaaw Nguu, Yaaw Yák and Waaw Wǎaen and Tone RulesDocumento5 pagineThai Alphabet Made Easy #2 Ngaaw Nguu, Yaaw Yák and Waaw Wǎaen and Tone RulesRobbyReyesNessuna valutazione finora

- Grammar IngDocumento2 pagineGrammar IngBere MerazNessuna valutazione finora

- PhonemicsDocumento31 paginePhonemicsm1d0r1Nessuna valutazione finora

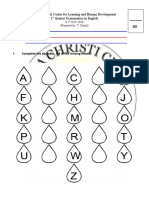

- Name:: Anima Christi Center For Learning and Human Development 1 Quarter Examination in EnglishDocumento7 pagineName:: Anima Christi Center For Learning and Human Development 1 Quarter Examination in EnglishChasil BonifacioNessuna valutazione finora

- Week 6:) Level 1 - Easy Level: Pair and ShareDocumento5 pagineWeek 6:) Level 1 - Easy Level: Pair and ShareCNessuna valutazione finora

- 199 2021 DT 24 09 2021 Promotion of Tech GR I FitterDocumento4 pagine199 2021 DT 24 09 2021 Promotion of Tech GR I FitterBalu kadamNessuna valutazione finora

- Intonation PresentationDocumento21 pagineIntonation PresentationNurhusna PutriNessuna valutazione finora

- Approaches in Teachg of GrammarDocumento68 pagineApproaches in Teachg of GrammarIzzati Aqillah RoslanNessuna valutazione finora

- Proc No. 16-1996 Flag and EmblemDocumento5 pagineProc No. 16-1996 Flag and Emblemshami mohammed100% (1)

- Age and The Critical Period Hypothesis Dr. AbelloDocumento3 pagineAge and The Critical Period Hypothesis Dr. AbelloCleanfaceNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson 3Documento9 pagineLesson 3leishroaster0100% (1)

- Essay 1 Are Culture and Language Separable? - 2Documento2 pagineEssay 1 Are Culture and Language Separable? - 2Bruno BragaNessuna valutazione finora

- Discourse AnalysisDocumento24 pagineDiscourse AnalysisVeasna ChannNessuna valutazione finora

- An Analysis of Spoken Grammar: The Case For Production: Simon MumfordDocumento8 pagineAn Analysis of Spoken Grammar: The Case For Production: Simon MumfordAsif RezaNessuna valutazione finora

- Needs AnalysisDocumento2 pagineNeeds AnalysisNico James Morales LaporeNessuna valutazione finora

- Lado, Comparison Grammatical StructuresDocumento7 pagineLado, Comparison Grammatical StructuresTihomir BozicicNessuna valutazione finora

- Full Korean Combined Vowels Guide KoreanDocumento5 pagineFull Korean Combined Vowels Guide KoreanSeason Ch'ngNessuna valutazione finora

- PMC - Module No: 06Documento13 paginePMC - Module No: 06TALHA ZAFAR80% (25)

- Answer Key PDFDocumento18 pagineAnswer Key PDFGömbicz GergelyNessuna valutazione finora

- Sumerian LanguageDocumento3 pagineSumerian LanguageYelhatNessuna valutazione finora

- Modality & Discourse Analysis and Phonology (Pronunciation) : Carmen Anahis Rdz. Cervantes Sarai Altamirano AltamiranoDocumento19 pagineModality & Discourse Analysis and Phonology (Pronunciation) : Carmen Anahis Rdz. Cervantes Sarai Altamirano Altamiranoaltamirano altamiranoNessuna valutazione finora

- Lecture 1 - The Concept of Word FormationDocumento38 pagineLecture 1 - The Concept of Word FormationArpit ChaudharyNessuna valutazione finora

- 3 Minute Egyptian ArabicDocumento121 pagine3 Minute Egyptian ArabicYasirSwati100% (1)

- Everyday Filipino GreetingsDocumento3 pagineEveryday Filipino Greetingszoltan2014Nessuna valutazione finora