Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Ig E

Caricato da

Rishiraj SahooTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Ig E

Caricato da

Rishiraj SahooCopyright:

Formati disponibili

ASIAN PACIFIC JOURNAL OF ALLERGY AND IMMUNOLOGY (2006) 24: 191-199

Relevance of Serum IgE Estimation in

Allergic Bronchial Asthma with

Special Reference to Food Allergy

Raj Kumar1, Bhanu P. Singh2, Prakriti Srivastava1, Susheela Sridhara2, Naveen Arora2 and

Shailendra N. Gaur1

SUMMARY Studies suggest the importance of serum total and specific IgE in clinical evaluation of allergic manifestations. Such studies are lacking in Indian subcontinent, though a large population suffer from bronchial asthma.

Here relevance of serum total and specific IgE was investigated in asthmatics with food sensitization. A total of 216

consecutive patients (mean age 31.9 years, S.D. 11.8) were screened by various diagnostic testing. Out of 216 patients, 172 were with elevated serum total IgE (201 to > 800 IU/ml). Rice elicited marked positive skin prick test reactions (SPT) in 24 (11%) asthma patients followed by black gram 22 (10%), lentil 21 (9.7%) and citrus fruits 20

(9.2%). Serum total IgE and specific IgE showed significant correlation, p = 0.005 and p = 0.001, respectively, with

positive skin tests. Blinded food challenges (DBPCFC) with rice and or black gram confirmed food sensitization in

28-37% of cases. In summary, serum total IgE of 265 IU/ml or more with marked positive SPT (4 mm or more) can

serve as marker for atopy and food sensitization. Specific IgE, three times of normal controls correlates well with

positive DBPCFC and offers evidence for the cases of food allergy.

Inflammation is the hallmark of bronchial

asthma, which results in airway hyperresponsiveness

and resistance to flow in the lower airways of

lungs.1,2 Various stimuli such as environmental allergens, psychic disturbances, infection, etc. are responsible for triggering inflammation and causing

mild, moderate or severe airflow obstruction in

asthmatics.3,4 After discovery of IgE antibody,5 attempts have been made to classify extrinsic asthma

from intrinsic asthma.6 Earlier studies suggest the

importance of serum total IgE in the pathophysiology of asthma and the development of airflow obstruction.3,4,7 Besides, a close association has been

reported between the presence of elevated total IgE

levels and symptomatic asthma.

Incidence of asthma has increased world

over including Asian countries.8,9 In India about 2-

8% population is estimated to suffer from bronchial

asthma with or without rhinitis.8 Like pollen and

other allergens, foods are also known to cause severe

systemic reactions and asthma in atopic individuals.

But in India, very few attempts are made to study

food sensitization and the allergic manifestations.10,11

Currently, the methods used to diagnose food allergy

include skin prick tests, measurement of food specific IgE, oral food challenges and double blinded

placebo controlled food challenge. Determination of

serum total IgE distinguishes atopic and/or nonatopic status of individuals.12,13 Skin prick testing

1

From the Department of Respiratory Medicine, Vallabhbhai

2

Patel Chest Institute, University of Delhi, Delhi-110007, Allergy

and Immunology Laboratory, Institute of Genomics and Integrative Biology (CSIR), Delhi University Campus, Delhi-110007, India.

Correspondence: Raj Kumar

E-mail: rajkumar_27563@yahoo.co.in

KUMAR, ET AL.

192

with allergen extracts is carried out to find out sensitization against offending allergens. Specific IgE estimation against respective allergen offers further

evidence14,15 to skin test results. However, all these

methods of diagnosis, even double blinded placebo

controlled food challenge may sometimes be misleading.16 In view of the shortcomings in individual

methods, the present study was undertaken to validate relevance of specific IgE estimations in diagnosing food allergy in asthmatics. Serum total IgE

levels in these patients were also correlated with skin

prick tests, oral food challenge and pulmonary obstruction.

nasal blockade, post nasal drip, etc. Various steps

involved in patient selection and testing in present

study are described in Fig. 1.

The patients (asthmatics) from both sexes

and non-smokers were included with history suggestive of atopy (inclusion criteria). Patients with other

associated pulmonary diseases including tuberculosis, COPD and systemic diseases, e.g. diabetes, hypertension and heart diseases were excluded (exclusion criteria) from the study. Patients with mechanical causes of airway obstruction, steroid dependent

and psychologically unstable cases were also excluded.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Two hundred sixteen patients of bronchial

asthma with or without rhinitis were included in the

present study from referred cases to Out Patient Department of V.P. Chest Institute, Delhi, in the years

2003-2004. These patients aged 8-65 years comprised 115 (53.2%) males and 101 (46.7%) females.

The patients were with history of food allergy as recorded using a standard questionnaire.17 The diagnosis of asthma was made based on history and

clinical investigation following the criteria of American Thoracic Society 1991.18 More than 15% reversibility of airway obstruction with 200 g of salbutamol was taken as criteria for diagnosing asthma.

The rhinitis19 was assigned to patients having any

two of the symptoms such as sneezing, rhinorrhea,

The written consent of each patient was obtained for participation in the study. The patients

were persuaded to give blood for serum total and

specific IgE estimation. The study protocol is approved by human ethics committee of the Institute.

Pulmonary function test

Spirometric evaluation of patients was done

as per American Thoracic Society guidelines18 with

Morgan Pulmolab equipment, England. The best of

the three readings were taken for assessing their

pulmonary function.

Skin prick tests (SPT)

Skin tests were carried out in 216 patients

with history suggestive of sensitization to food and

216 asthma patients (referred cases)

History & clinical investigation

(blood, X-ray, stool, physical examination, PFT [n = 182] etc.)

Skin prick tests (n = 216),

Normal (n = 41)

Serum total IgE estimation (n = 216)

NHS (n = 41 normal control)

Specific IgE estimation (n = 144)

NHS (n = 41 normal control)

Open food challenge

(n = 40, SPT+ELISA positive cases)

Blinded oral food challenge (DBPCFC)

(n = 30, SPT + ELISA positive cases)

Fig. 1 Flow chart describing the steps involved in patients selection and testing for the present study.

192

RELEVANCE OF SERUM IgE IN ASTHMA

193

common environmental allergens. The skin test reactions were graded after 20 minutes20 in comparison

to the wheal size of positive control, i.e. histamine

diphosphate (5 mg/ml). Skin tests with mean diameter of wheal three mm and above were considered as

marked positive reaction. For SPT, the allergen extracts (1:10 w/v, 50% glycerinated) were obtained

from Antigen Laboratory, Institute of Genomics and

Integrative Biology (CSIR), Delhi.

Total IgE estimation

Serum total IgE estimation21 was carried out

for each patient and normal control by enzymelinked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using

Pathozyme IgE kit (Omega Diagnostic Ltd, UK).

Monoclonal anti-IgE was coated into wells as per

manufacturers instruction. After washing, patients

serum diluted 1:10 v/v with the zero buffer was incubated for 30 minutes at 25C. Followed by washing, horse radish peroxidase conjugated anti-human

IgE was added and incubated for 30 minutes. The

color was developed by adding tetramethyl benzidene. The enzyme reaction was stopped with 100

l of hydrochloric acid. Absorbance was read at 450

nm using Dynatech ELISA reader.

Specific IgE estimation

Sera of patients showing marked positive

skin reactions were evaluated by ELISA for specific

IgE22 against respective food extract. Briefly, 2 g

protein (extract) was coated (100 l) per well in carbonate-bicrbonate buffer (pH 9.0) overnight at 4C.

After washing five times with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), unbound sites were blocked with 3%

BSA. Following washing, wells were incubated with

1:10 v/v diluted patients sera (100 l) overnight at

4C. The plate was washed again with PBS-Tween20 and incubated with horse radish peroxidase conjugated anti-human IgE for 4 hours at 37C. The

color was developed using O-phenylenediamine. The

reaction was stopped by adding 50 l of sulphuric

acid. Absorbance was read at 490 nm using an

ELISA reader.

Open food challenge (OFC)

In open food challenge test, the patients were

given orally 20-60 g of suspected food(s) as per the

history and kept under observation for 20 to 60 minutes. Spirometry evaluation was done before and af-

ter food challenge and fall in force vital capacity was

recorded. OFCs were performed under medical supervision and patients were asked to stay in the clinic

for at least 2 hours after the test. During the observation time blood pressure, pulse rate, forced expiratory volume in 1 second and peak expiratory flow

were measured. Subjects showing a positive OFC

were subsequently tested with DBPCFC.

Double blinded placebo controlled food challenge

(DBPCFC)

Double blinded placebo controlled food

challenges (DBPCFCs) were performed as per the

guidelines described earlier.23 Briefly, the active

food was masked to make it indistinguishable from

the placebo and was administered in double blinded

fashion, i.e. neither the patient nor the observer recording clinical manifestation knew about the content. The initial dose of food administered in

DBPCFC was chosen based on the results of OFC.

Approximately 20-30 g of the test food was sufficient to provoke allergic reactions in susceptible patients.

Spirometry evaluation, forced expiratory

volume at one second (FEV1) was made prior and after food challenge. The airflow obstruction (PFT)

was noted after food challenge test and obstruction

of more than 15% in FEV1 or 200 ml change was

taken as significant value. The patients who developed symptoms such as breathlessness, cough,

sneezing, rhinorrhea, vomiting and significant

changes in spirometry were scored as DBPCFC positive. The patients were kept under observation for at

least 2 hours after the food challenge test. In case of

anaphylactic reaction as a result of provocation the

patients were given epinephrine and avil and were

nebulized with salbutamol and ipratropium bromide.

Same ingredients of placebo were used in

both the active food and placebo. Placebo was selected from food materials which showed negative

SPT, ELISA (Specific IgE) and oral challenge test in

patients. The test recipe was usually prepared in the

ratio of 3:1 (Placebo:test food).

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using

SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) ver-

193

KUMAR, ET AL.

194

sion 10.5 software. The data was analyzed for all

variables using the Chi-square test. The comparison

was made between serum total IgE levels with pulmonary function, serum total IgE with skin prick test

and specific IgE with skin prick test and oral food

challenge test. The differences were considered to be

statistically significant at p = 0.05.

RESULTS

Out of 216 patients included in the present

study, 54 were suffering with asthma alone, whereas

162 had associated rhinitis. Most of the patients

were in the age group of 21-40 years with mean age

31.9 (SD 11.8). Serum total IgE was estimated in all

cases (n = 216) by ELISA. Age wise distribution of

total IgE values (IU/ml) has been presented in Table

1. Maximum patients (n = 56) with elevated IgE

(201 to > 800 IU/ml) were in 21-30 years age group

followed by 31-40 years (n = 54) and least (n = 12)

were in 51 years and above group. The serum total

IgE data was analyzed in two groups of patients: (a)

bronchial asthma alone and (b) asthma with associated rhinitis (Table 2). Altogether 61 patients showed

total IgE in the range of 201-400 IU/ml, 28 patients,

IgE 401-600 IU/ml and 44 patients showed IgE values, 601-800 IU/ml. Thirty-nine patients demonstrated serum total IgE > 800 IU/ml.

Out of the 216 cases, pulmonary function

test could be performed in 182 asthma patients to record air flow obstruction. The patients were categorized as normal (> 80% of the predicted FEV1), mild

(60-80% of the predicted FEV1), moderate (40-60%

of the predicted FEV1) and severe (< 40% of the predicted FEV1) on the basis of airflow obstruction.

Pulmonary obstruction (FEV1) and serum total IgE

values were analyzed for all asthmatics (with or

without rhinitis) and presented in Fig. 2. The total

IgE values in normal healthy volunteers (NHS, n =

41) ranged from 6-231 IU/ml. Mean 2SD was calculated and values > 265 IU/ml IgE were taken to

classify ELISA cut off for patients with significantly

elevated IgE levels (Fig. 2). Among the patients

with mild (n = 55) to moderate (n = 40) airflow obstruction, 40 and 27 patients, respectively demonstrated remarkably elevated IgE levels (265 IU/ml).

Severe airflow obstruction was recorded in 19 cases

Table 1 Serum total IgE values in different age groups of asthma patients

Age group

(years)

Total IgE (IU/ml)

Total

6-200

201-400

401-600

601-800

> 800

08-20

09

08

02

10

10

39

21-30

17

16

11

16

13

73

31-40

07

20

09

14

11

61

41-50

07

11

03

03

03

27

51 & above

04

06

03

01

02

16

Table 2 Distribution of serum total IgE in two groups of asthma patients

Total IgE (IU/ml)

Bronchial asthma

No.

Asthma with rhinitis

No.

Total

No. (%)

6-200

11

33

44 (20.4)

201-400

14

47

61 (28.2)

401-600

11

17

28 (13.0)

601-800

12

32

44 (20.4)

> 800

06

33

39 (18.1)

194

RELEVANCE OF SERUM IgE IN ASTHMA

195

and 15 of them demonstrated significantly elevated

IgE levels. Comparative analysis of the data showed

no statistically significant correlation (p = 0.815) between serum total IgE levels and pulmonary obstruction (PFT).

SPT reactivity of these patients (n = 216)

was evaluated with different food extracts (Table 3).

Rice extract elicited marked positive SPT in 24

(11%) patients followed by black gram 22 (10%),

lentil 21 (9.7%) and citrus fruits 20 (9.2%). The

food extracts such as pea, maize, French bean, Lima

bean, fish and mustard exhibited marked positive

skin reactivity in 5-6% patients. Many food extracts

demonstrated marked positive skin reactions in 2-4%

of the cases tested. Beside food extracts, these patients were skin tested with 9 dominant pollen allergen extracts. Some of the patients positive to foods

also showed marked positive skin reactivity to pollen

extracts. This may be due to co-sensitization or presence of cross reactive proteins in the extracts.

Specific IgE estimations were carried out in

sera of patients against 9 major food allergens (Table

4). About 60-91% of SPT positive patients showed

raised specific IgE levels. Specific IgE values three

times of normal control (OD = 0.27 or more) were

designated as ELISA positive. Comparative analysis

of marked positive SPT and specific IgE (n = 144)

showed significant correlation (p = 0.001). Serum

total IgE values (n = 216) showed highly significant

correlation (p = 0.005) against marked positive skin

tests.

Open food challenge (OFC) was carried out

in 40 SPT and ELISA (specific IgE) positive asthma

patients. The OFC was positive in 27 (67.5%) cases

tested with rice, black gram, citrus fruits, banana,

French bean and lentil. DBPCFCs conducted with

rice (n = 16) and black gram (n = 14) in SPT positive

cases, demonstrated positive challenges in 6 (37.5%)

and 4 (28.5%) cases, respectively. The patients suffered with breathlessness, cough, sneezing, rhinor-

1400

Total IgE (IU/ml)

1200

1000

800

600

400

Mean +2 SD

200

Mean + SD

NHS

Fig. 2

Mild

Moderate

Severe

Analysis of total IgE levels and airflow obstruction in bronchial asthma patients. Out of

182 asthma patients, 55 showed mild, 40 moderate and 19 severe airflow obstruction.

The remaining 68 asthmatics showed normal airflow obstruction at the time of testing

(data not included) mean + 2 SD of normal human sera (NHS, n = 41) was calculated

as given in parenthesis (ODs > 265 IU/ml).

195

KUMAR, ET AL.

196

rhea, vomiting, stomach upset etc. after the challenge

test. Specific IgE and DBPCFCs with rice and black

gram were correlated for 30 patients. The patients

with specific IgE, three times of normal control or

more (OD > 0.27) demonstrated positive DBPCFC.

DISCUSSION

Open food challenge (OFC) and/or double

blinded placebo controlled food challenge

(DBPCFC) are recommended to achieve definitive

diagnosis of food allergy.23 DBPCFCs are cumbersome, associated with risk and results of OFCs are

not always reliable. In recent years, some studies

have related the total and specific IgE levels in serum and respiratory symptoms in patients sensitized

to food or inhalant allergens.11,24,25 Choi et al.26 observed that sensitivity of skin test was higher than

specific IgE test, whereas the specificity of IgE test

was better than skin test. Therefore, both the tests

should be used in a complimentary manner.

Sampson and Ho27 have established cut off points in

the specific IgE serum levels for different foods that

can predict clinical reactivity after ingestion in 9095% of the group studied. In the present study, relevance of serum total IgE levels was evaluated in

terms of airway responsiveness, i.e. pulmonary obstruction in allergic asthmatics. The data for serum

total IgE and specific IgE against respective food allergen were collected, analyzed and correlated for

clinical use.

Previously serum total IgE levels were

shown to be related with age, genetic predisposition,

race, immune status and some disease processes.28

The upper limit for IgE in normal adults has been recorded in the range of 40.9 IU/ml to 200 IU/ml in

different studies.7,29 Lindeberg and Arroyave30 have

defined 100 IU/ml as the cutoff to differentiate allergic and non-allergic subjects. For children less than

Table 3 Skin prick tests (SPT) with food allergen extracts on patients of asthma (n = 216)

Sample

number

Allergen extracts

2+

No.

3+

No.

4+

No.

Total

No.

Rice

23

24

11.1

Black gram

19

22

10.1

Lentil

21

21

9.7

Citrus fruits*

15

20

9.2

Pea

10

13

6.0

Maize

11

13

6.0

5.5

Lima bean

French bean

12

11

12

Fish

5.5

11

5.0

10

11

Mustard

10

11

5.0

Peanut

09

12

4.1

Banana

09

4.1

13

Soybean

07

3.2

14

Coconut

07

3.2

15

Chicken

07

3.2

16

Radish

06

2.7

17

Almond

05

2.3

18

Carrot

05

2.3

19

Cashew nut

05

2.3

20

Wheat

04

1.8

Total food extracts tested (n = 38); food extracts (n = 15) not included here showed SPT +ve reactions in < 1% cases; 2+ to 4+ = markedly positive skin reactions.

*Citrus fruits include orange, grapes, mausami and lemon.

196

RELEVANCE OF SERUM IgE IN ASTHMA

197

Table 4 Specific IgE levels against food allergen extracts in skin prick test (SPT)

positive asthma patients

Sample

number

Allergen extracts

SPT +ve

Specific IgE positive*

No.

Rice

24

16

66.6

Black gram

22

16

72.7

Lentil

21

16

76.1

Citrus fruits

20

12

60.0

Pea

13

09

69.2

French bean

12

11

91.6

Lima bean

12

08

66.6

Mustard

11

07

63.6

Banana

09

07

77.7

* ELISA positive = ODs > 0.27 (three times of normal control), Normal control = 0.09.

one year of age, the cut off value of 10 IU/ml provided 100% specificity and sensitivity. In the present study, 265 IU/ml serum total IgE (mean 2SD

of NHS) was taken as cutoff for ELISA positive.

Based on this, 82 (45.1%) asthmatics showed mild,

moderate or severely impaired lung function (Fig. 2).

The patients with significantly elevated IgE levels

(201 to > 800 IU/ml) were in 21- 40 years age group.

But no statistically significant correlation was observed between age and total IgE levels in our study

(p = 0.12). Burrows et al.12 reported similar findings

about serum total IgE and rate of disease in different

age group patients. Shadick and co-workers31 observed association between serum total IgE concentrations at the early life with lower level of pulmonary function. But it is not predictive of accelerated

rate in decline of FEV1 among middle aged and

older man. Taylor and coworkers32 observed in a 7.5

years follow up study, that decline in FEV1 was unrelated to total serum IgE levels. This is in agreement

to our findings since no statistically significant correlation (p = 0.815) was observed between total IgE

levels and pulmonary obstruction in allergic asthmatics.

Earlier studies suggest that quantitation of

food specific IgE is a useful test for diagnosing allergy to milk, egg, peanut and fish.11,33 This could

eliminate the need of double blinded placebo controlled challenges in a significant number of subjects.

Garcia-Ara et al.34 also stated that, milk allergic

cases with positive SPT and 2.5 kU/l specific IgE or

greater should not be subjected to oral food challenges. In the present study, many asthmatics

showed food sensitization as evaluated by history

and skin prick tests (SPT). Specific IgE estimation

with 9 common food allergen extracts showed significantly raised levels in SPT positive cases. The

data for marked positive skin tests and specific IgE

showed statistically significant (p = 0.012) correlation. Among 40 SPT and ELISA positive (specific

IgE 3 times of control) cases, 27 (67.5%) patients

gave OFC positive test. However, no statistically

significant correlation (p = 0.608) was observed between higher specific IgE and open food challenge

positivity. DBPCFC carried out with rice and black

gram showed positive challenges in 37.5% to 28.5%

cases tested. The patients showing DBPCFC positive

were with marked positive skin tests (4 mm or more

wheal) and significantly elevated specific IgE (OD >

0.27, i.e. three times or more of normal control)

against respective food.

In conclusion, elevated serum total IgE levels (> 265 IU/ml) indicate towards atopic status of

patients, but it did not correlate with pulmonary obstruction in allergic asthmatics. Specific IgE three

times of control and skin prick tests 4 mm wheal or

more offer substantial evidence for food hypersensitivity in asthmatics. Based on this, the patients can

be advised to undertake avoidance measures against

the offending food allergen.

197

KUMAR, ET AL.

198

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was funded by grant from Indian

Council of Medical Research (ICMR), New Delhi.

The authors are thankful to Mr. Harsh Kumar (statistical analyst) for analysis of data.

16.

17.

18.

REFERENCES

1. Taylor KJ, Luksza AR. Peripheral blood eosinophil counts

and bronchial responsiveness. Thorax 1987; 42: 452-56.

2. Kuntz KM, Kitch BT, Fuhlbrigge AL, Paltiel AD, Weiss ST.

A novel approach to defining the relationship between lung

function and symptom status in asthma. J Clin Epidemiol

2002; 55: 11-8.

3. Peat JK, Salome CM, Woolcock AJ. Longitudinal changes in

atopy during a 4 year period, relation to bronchial hyperresponsiveness and respiratory symptoms in a population sample of Australian school children. J Allergy Clin Immunol

1990; 85: 65-74.

4. Sherrill DL, Lebowitz MD, Halonen M, Barbee RA, Burrows B. Longitudinal evaluation of the association between

pulmonary function and total serum IgE. Am J Respir Crit

Care Med 1995; 152: 98-102.

5. Johansson SGO, Bennich H. Immunological studies of an

atypical (myeloma) immunoglobin. Immunology 1967; 13:

381-94.

6. Humbert M, Menz G, Ying S, Corrigan CJ, Robinson DS,

Durham SR, Kay AB. The immunopathology of extrinsic

(atopy) and intrinsic (non-atopic) asthma: more similarities

than difference. Immunology Today 1999; 20: 528-33.

7. Annesi I, Oryszozyn MP, Frette C, Neukirch F, OrvoenFrija E, Kauffman F. Total circulating IgE and FEV1 in adult

men; an epidemiologic longitudinal study. Chest 1992; 101:

642-48.

8. Anonymous. Worldwide variation in prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and atopic eczema: ISAAC. Lancet 1998; 351: 1225-32.

9. Wong GWK, Leung TF, Fok TF. Asthma epidemiology and

hygiene hypothesis in Asia. Allergy Clin Immunol Int 2004;

16: 155-60.

10. Kumar R, Sridhara S, Verma J, Arora N, Singh BP. Clinicoimmunologic studies on allergy to pulses- a case report. Indian J Allergy Asthma Immunol 2000; 14: 7-12.

11. Patil SP, Niphadkar PV, Bapat MM. Chickpea a major food

allergen in the Indian subcontinent and its clinical and immunochemical correlation. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol

2001; 87: 140-5.

12. Burrows B, Bloom JW, Traver GA, Cline MG. The course

and prognosis of different forms of chronic airway obstruction in a sample from the general population. N Engl J Med

1987; 317: 1309-14.

13. Klinke M, Cline MG, Halonen M, Burrows B. Problems in

defining normal limits for serum IgE. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1990; 80: 440-4.

14. Clark MCA, Kilburn SA, Hourihane JOB, Dean KR, Warner

JO, Dean TP. Serological characteristics of peanut allergy.

Clin Exp Allergy 1998; 28: 1251-7.

15. Martinez TB, Garcia-Ara C, Diaz-Pena JM, Munoz FM,

Sanchez GG, Esteban MM. Validity of specific IgE antibod-

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

198

ies in children with egg allergy. Clin Exp Allergy 2001; 31:

1464-9.

Niggemann B, Beyer K. Diagnostic pitfalls in food allergy in

children. Allergy 2005; 60: 104-7.

Vally H, de Klerk N, Thompson PJ. Asthma induced by alcoholic drinks: a new Food Allergy Questionnaire. Aust NZJ

Public Health 1999; 23: 590-4.

American Thoracic Society. Lung function testing: selection

of reference values and interpretative strategies. Am Rev

Respir Dis 1991; 144: 1202-18.

Adamopoulous G, Monolopolous L, Giotakis I. A comparison of the efficacy and the patients acceptability of budesonide and beclomethasone dipropionate aqueous nasal sprays

in patients with perennial rhinitis. Clin Otolaryngol 1995;

20: 340-4.

Dreborg S. Skin testing- the safety of skin tests and the information obtained from using different methods and concentration of allergen. Allergy 1993; 48: 473-5.

Kumari D, Kumar R, Sridhara S, Arora N, Gaur SN, Singh

BP. Sensitization to black gram in patients with bronchial

asthma and rhinitis: clinical evaluation and characterization

of allergens. Allergy 2006; 61:104-110.

Voller A, Bidwel DE, Barlett A. Enzyme-linked immunosorbant assay. Manual of Clinical Immunology. Washington, DC, American Society of Microbiology, 1980.

Anonymous. American Gastroenterological Association

Medical Position Statement: guidelines for the evaluation of

food allergies. Gasteroenterology 2001; 120: 1023-5.

Pastorello EA, Incorvaia C, Ortolani C, et al. Studies on the

relationship between the level of specific IgE antibodies and

the clinical expression of allergy. I. Definition of levels distinguishing patients with symptomatic from patients with asymptomatic allergy to common aeroallergens. J Allergy Clin

Immunol 1995; 96: 580-7.

Kerkhof M, Dubois AE, Postma DS, Schouten JP, de Monchy JG. Role and interpretation of total serum IgE measurements in the diagnosis of allergic airway disease in adults.

Allergy 2003; 58: 905-11.

Choi IS, Koh YI, Koh JS, Lee MG. Sensitivity of the skin

prick test and the specificity of the serum specific IgE test

for airway responsiveness to house dust mites in asthma. J.

Asthma 2005; 42: 197-202.

Sampson HA, Ho DG. Relationship between food specific

IgE concentrations and the risk of positive food challenges in

children and adolescents. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1997; 100:

444-51.

Martinez FD, Holberg CJ, Halonen M, Morgan WJ, Wright

AL, Taussig LM. Evidence for Mendelian inheritance of serum IgE levels in Hispanic and non-Hispanic white families.

Am J Human Genet 1994; 55: 555-65.

Burrows B, Halonen M, Lebowitz MD, Knudsen RJ, Barbee

RJ. The relationship of serum immunoglobulin E, allergy

skin tests and smoking to respiratory disorders. J Allergy

Clin Immunol 1982; 70: 199-204.

Lindberg RE, Arroyave C. Levels of IgE in serum from

normal children and allergic children as measured by an enzyme immunoassay. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1986; 78: 614-8.

Shadick NA, Sparrow D, OConnor GT, DeMolles D, Weiss

ST. Relationship of serum IgE concentration to level and rate

of decline of pulmonary function: The Normative Aging

Study. Thorax 1996; 51: 787-92.

RELEVANCE OF SERUM IgE IN ASTHMA

199

32. Taylor RG, Joyce H, Gross E, Holland F, Pride NB. Bronchial reactivity to inhaled histamine and annual rate of decline in FEV1 in male smokers and ex-smokers. Thorax

1985; 40: 9-16.

33. Sampson HA. Utility of food specific IgE concentrations in

predicting symptomatic food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001; 107: 891-6.

34. Garcia-Ara C, Martinez TB, Diaz-Pena JM, Martin-Munoz

F, Reche-Frutos M, Martin-Esteban M. Specific IgE levels in

the diagnosis of immediate hypersensitivity to cows milk

protein in the infant. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001; 107:

185-90.

199

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Coal Mining Safety PDFDocumento204 pagineCoal Mining Safety PDFamiruddinNessuna valutazione finora

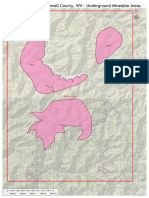

- Beckley Seam Underground Mineable AreaDocumento1 paginaBeckley Seam Underground Mineable AreaRishiraj SahooNessuna valutazione finora

- Table 28. Average Sales Price of Coal by State and Mine Type, 2018 and 2017Documento1 paginaTable 28. Average Sales Price of Coal by State and Mine Type, 2018 and 2017Rishiraj SahooNessuna valutazione finora

- USGS Time Scale FS10-3059 PDFDocumento2 pagineUSGS Time Scale FS10-3059 PDFcuiviewenNessuna valutazione finora

- FTG-10 Corridor H GuidebookDocumento89 pagineFTG-10 Corridor H GuidebookRishiraj SahooNessuna valutazione finora

- ReportDocumento46 pagineReportAlvin GuadizNessuna valutazione finora

- Mine Pool AtlasDocumento172 pagineMine Pool AtlasRishiraj SahooNessuna valutazione finora

- Coal Utilization - PrintDocumento16 pagineCoal Utilization - PrintRishiraj SahooNessuna valutazione finora

- Pub - Coal Camp Chronicles PDFDocumento261 paginePub - Coal Camp Chronicles PDFRishiraj SahooNessuna valutazione finora

- Properties Affecting Coal Utilization Coal RankDocumento37 pagineProperties Affecting Coal Utilization Coal RankRishiraj SahooNessuna valutazione finora

- Coal - A Complex Natural Resource - USGSDocumento6 pagineCoal - A Complex Natural Resource - USGSRishiraj SahooNessuna valutazione finora

- National Coal OverviewDocumento8 pagineNational Coal OverviewRishiraj SahooNessuna valutazione finora

- Coal Mining BritinicaDocumento28 pagineCoal Mining BritinicaRishiraj SahooNessuna valutazione finora

- Mine Pool AtlasDocumento172 pagineMine Pool AtlasRishiraj SahooNessuna valutazione finora

- ChapterF PDFDocumento198 pagineChapterF PDFRishiraj SahooNessuna valutazione finora

- Raoul Jacquand ContactDocumento1 paginaRaoul Jacquand ContactRishiraj SahooNessuna valutazione finora

- Holeid Projectcode Prospect East North RL Depth: Azimuth DIPDocumento2 pagineHoleid Projectcode Prospect East North RL Depth: Azimuth DIPRishiraj SahooNessuna valutazione finora

- Travel LogDocumento3 pagineTravel LogRishiraj SahooNessuna valutazione finora

- Fe Mag CalculationDocumento778 pagineFe Mag CalculationRishiraj SahooNessuna valutazione finora

- Clean Coal 2020-05-28Documento233 pagineClean Coal 2020-05-28Rishiraj SahooNessuna valutazione finora

- ChapterD PDFDocumento21 pagineChapterD PDFRishiraj SahooNessuna valutazione finora

- CoalDocumento20 pagineCoalShashankNessuna valutazione finora

- Executive Summary - CoalDocumento7 pagineExecutive Summary - CoalRishiraj SahooNessuna valutazione finora

- 2020 05 07 Clean - Coal - 1ftDocumento644 pagine2020 05 07 Clean - Coal - 1ftRishiraj SahooNessuna valutazione finora

- ChapterF PDFDocumento198 pagineChapterF PDFRishiraj SahooNessuna valutazione finora

- MIneral Comodity Summery Iron Ore-20198Documento2 pagineMIneral Comodity Summery Iron Ore-20198Rishiraj SahooNessuna valutazione finora

- Mineral Yearbook-Iron ORe-2016Documento13 pagineMineral Yearbook-Iron ORe-2016Rishiraj SahooNessuna valutazione finora

- Monthprod 2018 TotDocumento1 paginaMonthprod 2018 TotRishiraj SahooNessuna valutazione finora

- mcs2019 All PDFDocumento204 paginemcs2019 All PDFRheydel BartolomeNessuna valutazione finora

- Existing Gen Units 2017Documento12 pagineExisting Gen Units 2017Rishiraj SahooNessuna valutazione finora

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Ria ImmunoassayDocumento10 pagineRia ImmunoassayDinkey SharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Learning Activity Sheet in Science 10Documento10 pagineLearning Activity Sheet in Science 10Sheee ShhheshNessuna valutazione finora

- CytogeneticsDocumento5 pagineCytogeneticsDennyvie Ann D. CeñidozaNessuna valutazione finora

- Structure of ADC-68, a novel carbapenem-hydrolyzing class C extended-spectrum β-lactamase isolated from Acinetobacter baumanniiDocumento14 pagineStructure of ADC-68, a novel carbapenem-hydrolyzing class C extended-spectrum β-lactamase isolated from Acinetobacter baumanniigeerthi vasanNessuna valutazione finora

- 269 - Embryology Physiology) Development of The Heart  - ÏDocumento11 pagine269 - Embryology Physiology) Development of The Heart  - ÏFood Safety CommunityNessuna valutazione finora

- Genetic Influences in Human BehaviorDocumento24 pagineGenetic Influences in Human BehaviorGuillermo ArriagaNessuna valutazione finora

- ASNC AND EANM Amyloidosis Practice Points WEBDocumento12 pagineASNC AND EANM Amyloidosis Practice Points WEBElena FlorentinaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Nervous System PDFDocumento3 pagineThe Nervous System PDFPerry SinNessuna valutazione finora

- Biological Impact of Feeding Rats With A Genetically Modified-Based DietDocumento11 pagineBiological Impact of Feeding Rats With A Genetically Modified-Based DietJesús Rafael Méndez NateraNessuna valutazione finora

- Flow Cytometry: Surface Markers and Beyond: Methods of Allergy and ImmunologyDocumento10 pagineFlow Cytometry: Surface Markers and Beyond: Methods of Allergy and ImmunologyMunir AliNessuna valutazione finora

- Swyer SyndromeDocumento1 paginaSwyer SyndromeHaNessuna valutazione finora

- AutoimunDocumento23 pagineAutoimunEllya AfianiNessuna valutazione finora

- Biology SL P2Documento8 pagineBiology SL P2KenanNessuna valutazione finora

- Aplastic Hemolitic 2021 OlgaDocumento43 pagineAplastic Hemolitic 2021 OlgalaibaNessuna valutazione finora

- Lab Report 1: Dna Extraction From Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMC)Documento7 pagineLab Report 1: Dna Extraction From Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMC)Nida RidzuanNessuna valutazione finora

- Tay-Sachs DiseaseDocumento2 pagineTay-Sachs Diseaseapi-251963850Nessuna valutazione finora

- Resume CV Dr. Kang Zhang MD PHDDocumento15 pagineResume CV Dr. Kang Zhang MD PHDKang ZhangNessuna valutazione finora

- NCERT Books For Class 11 BiotechnologyDocumento336 pagineNCERT Books For Class 11 BiotechnologyPiyush MohapatraNessuna valutazione finora

- Calcinosis Cutis Report of 4 CasesDocumento2 pagineCalcinosis Cutis Report of 4 CasesEtty FaridaNessuna valutazione finora

- Referensi CK2Documento1 paginaReferensi CK2Rahma UlfaNessuna valutazione finora

- Neural Control of MasticationDocumento34 pagineNeural Control of MasticationAnonymous k8rDEsJsU10% (1)

- Chab MTO 8e Mod 2 Final QuizDocumento24 pagineChab MTO 8e Mod 2 Final Quizshawnas09100% (1)

- Chemical Carcinogenesis I and Ii: Michael Lea 2016Documento31 pagineChemical Carcinogenesis I and Ii: Michael Lea 2016aasiyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Lymphomas: Varun. M M-Pharm (Pharmacology) IyriisemDocumento32 pagineLymphomas: Varun. M M-Pharm (Pharmacology) IyriisemPintoo Pintu100% (2)

- Leprosy: Pathogenesis Updated: ReviewDocumento15 pagineLeprosy: Pathogenesis Updated: ReviewagneselimNessuna valutazione finora

- Peripheral Neuropathy Associated With Mitochondrial Disease in ChildrenDocumento8 paginePeripheral Neuropathy Associated With Mitochondrial Disease in ChildrenRenata CardosoNessuna valutazione finora

- Brain Tumor SymtomsDocumento3 pagineBrain Tumor SymtomsvsalaiselvamNessuna valutazione finora

- Amniotic Fluid and ItDocumento8 pagineAmniotic Fluid and ItSaman SarKoNessuna valutazione finora

- Cancer Cells Induce Metastasis-Supporting Neutrophil Extracellular DNA TrapsDocumento13 pagineCancer Cells Induce Metastasis-Supporting Neutrophil Extracellular DNA TrapsJoe DaccacheNessuna valutazione finora

- Biology 1010 General ObjectivesDocumento2 pagineBiology 1010 General Objectivesapi-241247043Nessuna valutazione finora