Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Assessment: The Psychopathy Q-Sort: Construct Validity Evidence in A Nonclinical Sample

Caricato da

Corina IcaTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Assessment: The Psychopathy Q-Sort: Construct Validity Evidence in A Nonclinical Sample

Caricato da

Corina IcaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Assessment

http://asm.sagepub.com

The Psychopathy Q-Sort: Construct Validity Evidence in a Nonclinical Sample

Katherine A. Fowler and Scott O. Lilienfeld

Assessment 2007; 14; 75

DOI: 10.1177/1073191106290792

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://asm.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/14/1/75

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

Additional services and information for Assessment can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://asm.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://asm.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Citations http://asm.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/14/1/75

Downloaded from http://asm.sagepub.com at NIH Library on November 13, 2009

The Psychopathy Q-Sort

Construct Validity Evidence in a Nonclinical Sample

Katherine A. Fowler

Scott O. Lilienfeld

Emory University

Scant research has examined the validity of instruments that permit observer ratings of

psychopathy. Using a nonclinical (undergraduate) sample, the authors examined the associations between both self- and observer ratings on a psychopathy prototype (Psychopathy

Q-Sort, PQS) and widely used measures of psychopathy, antisocial behavior, and negative

emotionality. Self- and observer prototype correlations generally displayed predicted patterns of convergent and discriminant validity for the PQS. Future research using the PQS

should focus on potential domains of incremental validity of peer-rated psychopathy

beyond self-reported psychopathy.

Keywords: psychopathy; personality assessment, peer reports

The assessment of psychopathy has long been

embroiled in controversy (Lilienfeld & Fowler, 2006).

One major limitation in this literature has been the

paucity of measures to permit the detection of psychopathy by observers (Lilienfeld, 1998; Lilienfeld & Fowler,

2006). Observers may possess access to important information regarding individuals psychopathic traits that is

missed by self-report measures or interviews. In this way,

they may be able to fill in the blind spots ostensibly

generated by psychopathic individuals lack of awareness

of their own shortcomings (Grove & Tellegen, 1991).

Indeed, in his classic clinical description of psychopathy, Cleckley (1941/1988) listed specific loss of insight

as a core feature of the construct, supporting the argument that exclusive reliance on self-reports may result in

an incomplete picture of this condition. According to

Cleckley, the psychopath possesses no capacity to see

himself as others see him (p. 350). Goughs (1960) roletaking theory of psychopathy adds to this the implication

that psychopaths have a difficult time placing adopting

the perspectives of others. Moreover, psychopathic individuals propensities toward narcissism and externalization of blame may sharply constrain their capacity to

report validly on their undesirable attributes (Lilienfeld,

1994). The paucity of research on the assessment of psychopathic traits by observers is therefore surprising.

In an effort to fill this void, Reise and Oliver (1994)

developed a Q-sort measure (the Psychopathy Q-Sort,

or PQS) to permit the assessment of psychopathy by

observers. They asked seven judges with expertise in psychopathy to sort the 100 items of the California Q-set

(CAQ; Block, 1961) according to their conceptualization

of a prototypical psychopath. In contrast to other commonly used measures of psychopathy, the PQS was

designed explicitly to permit completion by both observers

and target participants. As a consequence, it permits a

direct examination of the incremental validity of observer

reports beyond self-reports of psychopathy, and viceversa, that is not confounded by measure. In addition, by

forcing observers to sort items into the same quasi-normal

distribution, the PQS eliminates certain response biases,

such as a tendency to provide extreme item ratings.

Reliability of the PQS prototype aggregated over

seven judges was .90, and it correlated r = .51 (p < .01)

with a CAQ narcissism prototype but only r = .16 (ns)

with a CAQ hysteria prototype (Reise & Oliver, 1994). In

a community sample (N = 350), Reise and Wink (1995)

found that the PQS was positively associated with features

Please address correspondence to Katherine A. Fowler, M. A., Department of Psychology, Emory University, 532 Kilgo Circle,

Atlanta, GA 30322; e-mail: kfowle2@emory.edu.

Assessment, Volume 14, No. 1, March 2007 75-79

DOI: 10.1177/1073191106290792

2007 Sage Publications

Downloaded from http://asm.sagepub.com at NIH Library on November 13, 2009

76 ASSESSMENT

of Cluster B personality disorders (e.g., antisocial, borderline), negligibly or negatively associated with features

of other personality disorders, and negatively associated

with scores on the California Psychological Inventory

Socialization (So) Scale (Gough, 1994). Although the

So scale is sometimes scored in reverse as a measure of

psychopathy, most studies indicate that it is primarily an

indicator of nonspecific behavioral deviance rather than

the core affective and interpersonal traits of psychopathy

(Harpur, Hare, & Hasktian, 1989). There is no further

published evidence concerning the construct validity of

the PQS.

Several recent studies have addressed the potential

value of peer reports in the assessment of personality disorder (PD) features. Across studies, self-reported DSM-IV

PD traits exhibit low-to-moderate correlations with peerreported PD traits (median r = .36; Klonsky, Oltmanns, &

Turkheimer, 2002). In addition, peer reports of PD features

predict unique variance beyond self-reports for such

outcomes as military job functioning, active duty status

(Fiedler, Oltmanns, & Turkheimer, 2002), interpersonal

problems (Clifton, Turkheimer, & Oltmanns, 2004), and

long-term global adaptive functioning (Klein, 2003).

Recent findings also have revealed that peer reports exhibit

significant incremental validity beyond self-reports in predicting expert-rated, five factor model, antisocial personality disorder prototype scores (R2 = .12; Miller, Pilkonis,

& Morse, 2004). Nevertheless, there are scant data concerning the construct validity of peer reports in the assessment of psychopathy (cf. Cale & Lilienfeld, 2002).

In a recent study using taxometric analyses to examine the latent structure of the self-report Psychopathic

Personality Inventory (PPI; Lilienfeld & Andrews,

1996), Marcus, John, and Edens (2004) found that psychopathy appears to be underpinned by a dimension

(i.e., continuum) rather than a taxon, namely, a category

existing in nature (see Edens, Marcus, Lilienfeld,

& Poythress, 2006, for similar findings using the

Psychopathy ChecklistRevised [Hare, 2003], a semistructured interview measure of psychopathy). These

findings raise the possibility that psychopathic traits can

profitably be studied in nonclinical (e.g., student)

samples. Moreover, an emerging body of research

demonstrates that self-report and interview-based measures of psychopathy possess adequate construct validity

in nonclinical samples (Lilienfeld & Andrews, 1996; see

Lilienfeld, 1998, for a review).

The primary goal of this project is to provide further

information concerning the construct validity of the PQS

by examining its convergent and discriminant relations

with self and peer measures of psychopathy, self-reported

antisocial behavior, and global distress in an undergraduate sample.

METHOD

Participants

The sample of target participants (N = 65, 75% women)

was drawn from the undergraduate psychology research

pool at a midsize private university in the Southeast. Their

ages ranged from 18 to 26, with a mean of 18.9 (SD = 1.4).

Participants were 76.6% Caucasian, 7.8% African American,

10.9% Asian, and 4.7 % other ethnicities.

A total of N = 60 (68% women) peers nominated by

target subjects participated. For 21 target participants,

2 peers completed the task while 1 peer participated for

18 others. Peers ranged in age from 18 to 22, with a mean

of 19.3 (SD = 1.4), and were 60% Caucasian, 3% African

American, 15% Asian, and 15% other ethnicities. Peers

length of acquaintance with target participants ranged

from less than a month to 13 years, with a mean of 1.3

years and a median of 9.6 months (SD = .79).

Measures and Procedure

Target participants first completed a card-sorting task

consisting of 100 descriptive statements about personality

(the CAQ; Block, 1961) sorted into a forced quasi-normal

distribution of nine categories, from most uncharacteristic to most characteristic. Although the CAQ contains

some items that are psychodynamically oriented, it can be

comfortably used by raters of any theoretical orientation.

Next, they were administered (a) two self-report psychopathy measures, the short form of the Psychopathic

Personality Inventory (PPI; Lilienfeld & Andrews, 1996;

see Lilienfeld & Hess, 2001, for psychometric information regarding the PPI short form), which yields both a

global score and scores on eight subscales (e.g., Social

Potency, Coldheartedness, Fearlessness) and the Levenson

Primary and Secondary Psychopathy Scales (LPSP;

Levenson, Kiehl, & Fitzpatrick, 1995); (b) a measure of

antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) symptoms, the

Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire-4+ ASPD scale

(PDQ-4+ ASPD; Hyler & Rieder, 1994); and (c) a measure of global distress, the Negative Emotionality-30

(NEM-30; Waller, Tellegen, McDonald, & Lykken, 1996;

see Table 1 for Ms and SDs of all measures within this

sample). The mean scores and standard deviations in this

sample closely resemble those found in college samples in

prior research. For example, Lilienfeld and Hess (2001)

found comparable estimates for LPSP scores, 28.72

(7.18), primary psychopathy, 20.34 (4.27), secondary psychopathy; PPI total scores, 118.99 (16.32); PPI 1 and 2,

78.08 (13.44), 40.71 (7.97); and NEM-30 total scores,

10.71 (5.46). We administered the NEM-30 to provide

a discriminant validity target for the PQS because we

Downloaded from http://asm.sagepub.com at NIH Library on November 13, 2009

Fowler, Lilienfeld / SELF AND PEER PSYCHOPATHY Q-SORT 77

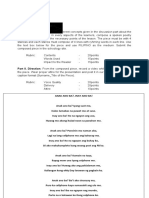

TABLE 1

Means and Standard Deviations of Scales and Subscales

Measure

Levenson primary and secondary psychopathy total

Levenson primary psychopthy

Levenson secondary psychopathy

Psychopathic Personality Inventory (PPI) total

PPI Machiavellian egocentricity

PPI Social potency

PPI Coldheartedness

PPI Carefree nonplanfulness

PPI Fearlessness

PPI Blame externalization

PPI Impulsive nonconformity

PPI Social introversion

Negative emotionality total

Antisocial behavior total (PDQ-4+ ASPD)

Peer Q-correlation aggregated

Self Q-correlation

SD

48.34

28.35

19.98

122.78

14.64

19.48

13.00

13.35

15.83

12.59

15.06

18.92

9.05

1.92

0.14

0.19

10.50

7.78

4.28

14.51

3.76

4.34

3.17

2.66

4.65

4.48

4.15

3.42

4.79

2.04

0.15

0.15

NOTE: PDQ-4+ ASPD = Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire, Antisocial Personality Disorder scale.

wanted to exclude the hypothesis that this instrument is

merely a measure of generalized emotional maladjustment. All of these measures have been found to possess

good reliability and construct validity in previous studies.

Peers were instructed to complete the CAQ by describing the target participant by whom they were nominated.

In cases in which two peers completed the CAQ, their

PQS scores were averaged.

In the analyses reported here, the target and peer Q-sorts

derived from the CAQ were correlated with the PQS prototype, and these correlations (i.e., Q-correlations) were

themselves used in correlational analyses.

RESULTS

We first computed correlations between the PQS and

other measures separately in men and women. Because

these correlations were extremely similar, we present

only combined analyses here. The correlation between

peer and self Q-correlations was moderate and statistically

significant (r = .32).1 Mean peer and self Q-correlations

(r = .14, r = .19) did not differ significantly (z = .24,

p = .80). Self Q-correlations correlated moderately and

significantly with LPSP primary, secondary, and total

psychopathy scores; PPI total scores; and several PPI

subscales (viz., Machiavellian Egocentricity, Social Potency,

Coldheartedness, Fearlessness, Impulsive Nonconformity,

and Stress Immunity; see Table 2). Self Q-correlations

correlated moderately and significantly with self-reported

ASPD symptoms but were virtually uncorrelated with the

NEM-30.

Peer Q-correlations correlated significantly and

moderately with PPI total scores, PPI Fearlessness, and

self-reported ASPD symptoms. In contrast, the correlations with the LPSP scales and the other PPI subscales

were nonsignificant. Peer Q-correlations also correlated

nonsignificantly with the NEM-30.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study offer preliminary but generally promising support for the convergent and discriminant validity of the PQS as completed by both target

participants and observers. These results suggest that the

PQS, although derived from items intended for clinical

raters, can be used validly by lay observers. Self and peer

Q-correlations correlated significantly with the PPI total

score and antisocial behavior self-ratings, and were negligibly correlated with a measure of negative emotionality.

These findings contribute to a small but emerging body

of evidence (e.g., Reise & Oliver, 1994; Reise & Wink,

1995) that the PQS is a construct valid measure and are

the first to demonstrate its convergence with wellvalidated psychopathy measures. In addition, our findings provide evidence for the PQSs discriminant validity

by demonstrating its independence from global distress.

Our study was marked by two major methodological

limitations. First, statistical power was limited due to a

lower than anticipated peer response rate. Second, most

peers have been acquainted with target subjects for less

than a year. Self- and peer ratings tend to correlate more

highly in older samples, possibly due to length of acquaintance (Klonsky et al., 2002). Nevertheless, subsidiary

moderator analyses not reported here revealed no significant associations between observers length of acquaintance with participants and self-peer correlations.

Downloaded from http://asm.sagepub.com at NIH Library on November 13, 2009

78 ASSESSMENT

TABLE 2

Correlations Among Self PQS Scores, Peer PQS Scores, Self-Report Measures

of Psychopathy, Antisocial Behavior, and Negative Emotionality

Measure

1. Self PQS

2. Peer PQS

3. Levenson total

4. LPPS

5. LSPS

6. PPI total

7. PPI ME

8. PPI SP

9. PPI COLD

10. PPI CN

11. PPI FEAR

12. PPI BE

13. PPI IN

14. PPI SI

15. NEM-30

16. PDQ-4+ ASPD

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

.32*

.57*

.55*

.42*

.67*

.48*

.31*

.38*

.17

.31*

.12

.44*

.31*

.05

.50*

.27

.25

.22

.38*

.22

.13

.16

.24

.38*

.05

.26

.14

.15

.36*

.93*

.76*

.42*

.75*

.25*

.29*

.52*

.13

.14

.26*

.11

.36*

.43*

.47*

.35*

.74*

.21

.32*

.40*

.11

.01

.17

.02

.21

.36*

.40*

.50*

.23

.14

.57*

.13

.37*

.32*

.23

.49*

.41*

.53*

.30*

.40*

.34*

.68*

.37*

.74*

.39*

.09

.53*

.14

.17

.37*

.36*

.08

.30*

.06

.34*

.45*

.06

.34*

.11

.06

.02

.39*

.30*

.02

.19

.05

.08

.22

.10

.06

.07

.18

.05

.20

.09

.06

.38*

.06

.62*

.19

.05

.47*

.29*

.13

.43*

.22

.10

.25

.34*

.46*

.04

.18

NOTE: Self PQS = Self Q-correlations with psychopathy prototype; Peer PQS = Aggregated peer Q-correlations with psychopathy prototype; LPPS =

Levenson primary psychopathy scale; LSPS = Levenson secondary psychopathy scale; PPI Tot = Psychopathic Personality Inventory total score; PPI

ME = PPI Machiavellian Egocentricity; PPI SP = PPI Social Potency; PPI COLD = PPI Coldheartedness; PPI CN = PPI Carefree Nonplanfulness; PPI

FEAR = PPI Fearlessness; PPI BE = PPI Blame Externalization; PPI IN = PPI Impulsive Nonconformity; PPI SI = PPI Stress Immunity; NEM-30 =

Negative Emotionality-30; PDQ-4+ ASPD = Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire, Antisocial Personality Disorder scale. Internal consistency estimates (Cronbachs s) are on the diagonal. Ns = 65 (target participants) and 60 (aggregated peer scores).

*p < .05.

Although our findings provide preliminary support for

the construct validity of the PQS with self- and peer

reporters, further research employing a larger sample is

needed. Low power was a significant limitation in this

study: With an N of 65 target subjects, correlations less than

r = .25 could not be detected as significant, and with only

N = 60 peer reporters, correlations less than r = .40 could

not be detected as significant. In addition, it will be important to determine whether these findings generalize to

samples presumably marked by higher levels of psychopathic traits, including prison and substance abuse samples.

Finally, data from participants who are better acquainted

with their peers could reveal important pockets of incremental validity of observer reports beyond self-reports.

Although not presented here, we conducted subsidiary

multiple regression analyses to examine possible areas of

incremental validity of peer reports beyond self-reports.

Such analyses are particularly stringent because they do

not confound mode of assessment (i.e., self vs. other) with

measure. These results provided suggestive (i.e., marginally significant at p = .05) evidence for the incremental

validity of observer reports beyond self-reports for only

one measure, namely, PPI Fearlessness, but these largely

negative findings are difficult to interpret in light of the low

statistical power of our investigation. Future research

efforts should focus on the examination of incremental

validity of peer and self-reports of psychopathy beyond

one another in larger samples as well as on the selection of

new criterion variables (e.g., laboratory measures of passive avoidance; see Hiatt & Newman, 2006), preferably

those free of the method variance limitations imposed by

reliance on self-reports.

NOTE

1. Peer Q-correlations correlated at r = .20 (ns, N = 21). The small

sample must be borne in mind when interpreting this correlation

because correlations less than r = .50 cannot be detected as significant

with a sample of this size.

REFERENCES

Block, J. (1961). The Q-sort method in personality assessment and psychiatric research. Springfield, IL: Thomas.

Cale, E. M., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2002). Histrionic personality disorder

and antisocial personality disorder: Sex differentiated manifestations of psychopathy? Journal of Personality Disorders, 16, 52-72.

Cleckley, H. (1988). The mask of sanity. St. Louis: Mosby. (Original

work published 1941)

Clifton, A., Turkheimer, E., & Oltmanns, T. F. (2004). Contrasting perspectives on personality problems: Descriptions from self and others. Personality and Individual Differences, 36, 1499-1514.

Edens, J. F., Marcus, D. K., Lilienfeld, S. O., & Poythress, N. G. (2006).

Psychopathic, not psychopath: Taxometric evidence for the dimensional structure of psychopathy. Journal of Abnormal Psychology,

115, 131-144.

Downloaded from http://asm.sagepub.com at NIH Library on November 13, 2009

Fowler, Lilienfeld / SELF AND PEER PSYCHOPATHY Q-SORT 79

Fiedler, E. R., Oltmanns, T. F., & Turkheimer, E. (2002). Traits associated

with personality disorders and adjustment to military life: Predictive

validity of self- and peer reports. Military Medicine, 169, 207-211.

Gough, H. G. (1960). Theory and method of socialization. Journal of

Counseling and Clinical Psychology, 24, 23-30.

Gough, H. G. (1994). Theory, development, and interpretation of the

CPI Socialization scale. Psychological Reports, 75, 651-700.

Grove, W. M., & Tellegen, A. (1991). Problems in the classification of

personality disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders, 5, 31-41.

Hare, R. D. (2003). The Psychopathy ChecklistRevised (2nd ed.).

Toronto, Canada: Multi-Health Systems.

Harpur, T. J., Hare, R. D., & Hakstian, R. (1989). A two-factor conceptualization of psychopathy: Construct validity and implications for

assessment. Psychological Assessment, 1, 6-17.

Hiatt, K. D., & Newman, J. P. (2006). Understanding psychopathy: The

cognitive side. In C. J. Patrick (Ed.), Handbook of psychopathy

(pp. 334-352). New York: Guilford.

Hyler, S. E., & Rieder, R. O. (1994). Personality Diagnostic

Questionnaire-4+. New York: Author.

Klein, D. N. (2003). Patients versus informants reports of personality

disorders in predicting 7 year outcome in outpatients with depressive disorders. Psychological Assessment, 15, 216-222.

Klonsky, E. D., Oltmanns, T. F., & Turkheimer, E. (2002). Informant

reports of personality disorder: Relation to self-reports and future

research. Clinical Psychology: Science & Practice, 9, 300-311.

Levenson, M. R., Kiehl, K. A., & Fitzpatrick, C. M. (1995). Assessing

psychopathic attributes in a non-institutionalized populations.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 151-158.

Lilienfeld, S. O. (1994). Conceptual problems in the assessment of psychopathy. Clinical Psychology Review, 14, 17-38.

Lilienfeld, S. O. (1998). Methodological advances and developments in

the assessment of psychopathy. Behaviour Research and Therapy,

36, 99-125.

Lilienfeld, S. O., & Andrews, B. P. (1996). Development and preliminary

validation of a self-report measure of psychopathic personality traits

in non-criminal populations. Journal of Personality Assessment, 66,

488-524.

Lilienfeld, S. O., & Fowler, K. A. (2006). The self-report assessment of

psychopathy: Problems, pitfalls, and promises. In C. J. Patrick (Ed.),

Handbook of psychopathy (pp. 107-132). New York: Guilford.

Lilienfeld, S. O., & Hess, T. H. (2001). Psychopathic personality traits

and somatization: Sex differences and the mediating role of negative emotionality. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral

Assessment, 23, 11-24.

Marcus, D. K., John, S. L., & Edens, J. F. (2004). A taxometric analysis of psychopathic personality. Journal of Abnormal Psychology,

113, 626-635.

Miller, J. D., Pilkonis, P. A., & Morse, J. Q. (2004). Five-factor model

prototypes for personality disorders: The utility of self-reports and

observer ratings. Assessment, 11, 127-138.

Reise, S. P., & Oliver, C. J. (1994). Development of a California Q-set

indicator of primary psychopathy. Journal of Personality Assessment,

62, 130-144.

Reise, S. P., & Wink, P. (1995). Psychological implications of the

Psychopathy Q-Sort. Journal of Personality Assessment, 65, 300-312.

Waller, N. G., Tellegen, A., McDonald, R. P., & Lykken, D. T. (1996).

Exploring nonlinear models in personality assessment: Development

and preliminary validation of a negative emotionality scale. Journal

of Personality, 64, 545-576.

Katherine A. Fowler is an advanced graduate student in the clinical psychology program at Emory University (anticipated graduation summer 2007). She has published several article and

chapters focusing on the assessment and diagnosis of psychopathy.

Scott O. Lilienfeld is associate professor of psychology (clinical psychology program) at Emory University in Atlanta, GA

and editor-in-chief of the Scientific Review of Mental Health

Practice. His research interests include the assessment and

etiology of psychopathic personality and the classification of

psychopathology.

Downloaded from http://asm.sagepub.com at NIH Library on November 13, 2009

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Jorge Arthur Brinkely, 2001Documento18 pagineJorge Arthur Brinkely, 2001Deivson Filipe BarrosNessuna valutazione finora

- Disfunkcionalna Uverenja I Ant PLDocumento12 pagineDisfunkcionalna Uverenja I Ant PLNađa FilipovićNessuna valutazione finora

- Calamaras, M. R., Reviere, S. L., Gallagher, K. E., & Kaslow, N. J. (2016) - Changes in Differentiation-Relatedness During PsychoanalysisDocumento8 pagineCalamaras, M. R., Reviere, S. L., Gallagher, K. E., & Kaslow, N. J. (2016) - Changes in Differentiation-Relatedness During PsychoanalysisLorenaUlloaNessuna valutazione finora

- Maladaptive Schemas, Irrational Beliefs, and Their Relationship With The Five-Factor Personality ModelDocumento13 pagineMaladaptive Schemas, Irrational Beliefs, and Their Relationship With The Five-Factor Personality ModelAna GeorgescuNessuna valutazione finora

- Brazil and Forth 2016 PCL SpringerDocumento6 pagineBrazil and Forth 2016 PCL SpringerBif FlaviusNessuna valutazione finora

- Schema PDFDocumento11 pagineSchema PDFCaterina MorosanuNessuna valutazione finora

- Psychoanalysis AlexythimiaDocumento36 paginePsychoanalysis AlexythimiaJimy Moskuna100% (1)

- PDF 65750 81433Documento13 paginePDF 65750 81433Viktor NassifNessuna valutazione finora

- Can Personality Assessment Predict Future Depression 2006Documento10 pagineCan Personality Assessment Predict Future Depression 2006Olivera VukovicNessuna valutazione finora

- Skee M Backgr Paper 12Documento14 pagineSkee M Backgr Paper 12GERMÁN ANDRÉS GUEVARANessuna valutazione finora

- The Treatment of Schizoid Personality Disorder Using Psychodynamic MethodsDocumento25 pagineThe Treatment of Schizoid Personality Disorder Using Psychodynamic MethodsnikhilNessuna valutazione finora

- An Investigation of The Perfectionism/Self-criticism Domain of The Personal Style InventoryDocumento16 pagineAn Investigation of The Perfectionism/Self-criticism Domain of The Personal Style InventoryParsa ShomaliNessuna valutazione finora

- The Structural Approach in Psychological Testing: Pergamon General Psychology SeriesDa EverandThe Structural Approach in Psychological Testing: Pergamon General Psychology SeriesNessuna valutazione finora

- Psychoanalytic Theory As A Unifying Framework For 21ST Century Personality AssessmentDocumento20 paginePsychoanalytic Theory As A Unifying Framework For 21ST Century Personality AssessmentPaola Martinez Manriquez100% (1)

- A Five-Factor Measure of Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Traits PDFDocumento38 pagineA Five-Factor Measure of Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Traits PDFRANJINI.C 20PSY042Nessuna valutazione finora

- Detecting Psychopathy From Thin Slices of Behavior: Katherine A. Fowler and Scott O. Lilienfeld Christopher J. PatrickDocumento11 pagineDetecting Psychopathy From Thin Slices of Behavior: Katherine A. Fowler and Scott O. Lilienfeld Christopher J. PatrickVasco PereiraNessuna valutazione finora

- ContentServer ArticuloDocumento25 pagineContentServer ArticuloKAREN ANDREA VILLAMARIN GALVIZNessuna valutazione finora

- Measuring Differentiation SelfDocumento9 pagineMeasuring Differentiation SelfDeborah NgaNessuna valutazione finora

- Projective Psychology - Clinical Approaches To The Total PersonalityDa EverandProjective Psychology - Clinical Approaches To The Total PersonalityNessuna valutazione finora

- Validation of DSM-5 Clinician-Rated Measures of Personality PathologyDocumento6 pagineValidation of DSM-5 Clinician-Rated Measures of Personality PathologyG. S.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Aggressivity, Narcissism, and Self-Destructiveness in The Psychotherapeutic Relationship - Otto KernbergDocumento27 pagineAggressivity, Narcissism, and Self-Destructiveness in The Psychotherapeutic Relationship - Otto Kernbergvgimbe100% (1)

- The Anaclitic-Introjective Depression Assessment: Development and Preliminary Validity of An Observer-Rated MeasureDocumento42 pagineThe Anaclitic-Introjective Depression Assessment: Development and Preliminary Validity of An Observer-Rated Measureyeremias setyawanNessuna valutazione finora

- The Case of Jane - A Pinean ApproachDocumento20 pagineThe Case of Jane - A Pinean ApproachSoraya RamosNessuna valutazione finora

- Literature Review On Social AnxietyDocumento9 pagineLiterature Review On Social Anxietyafmzvadyiaedla100% (1)

- Sociotropy, Autonomy, and Self-CriticismDocumento10 pagineSociotropy, Autonomy, and Self-Criticismowilm892973100% (1)

- Robson Selfesteem 1989Documento6 pagineRobson Selfesteem 1989Adnan AdilNessuna valutazione finora

- PBQ Short FormDocumento15 paginePBQ Short Formomr dogar0% (1)

- Braziland Forth 2016 PCLSpringerDocumento6 pagineBraziland Forth 2016 PCLSpringeralexandra gheorgheNessuna valutazione finora

- Vocational Psychology: Its Problems and MethodsDa EverandVocational Psychology: Its Problems and MethodsNessuna valutazione finora

- SRP2015 GordtsetalDocumento7 pagineSRP2015 GordtsetalClaudio AntonioNessuna valutazione finora

- Hare & Neumann Oxford Textbook 2009Documento30 pagineHare & Neumann Oxford Textbook 2009Noa LewinNessuna valutazione finora

- Evaluation of The Hare P-SCAN in A Non-Clinical Population: Cristal E. Elwood, Norman G. Poythress, Kevin S. DouglasDocumento11 pagineEvaluation of The Hare P-SCAN in A Non-Clinical Population: Cristal E. Elwood, Norman G. Poythress, Kevin S. DouglasJer SolNessuna valutazione finora

- Review of The Self-Sacrifice Dimension of The Dimensional Clinical Personality InventoryDocumento8 pagineReview of The Self-Sacrifice Dimension of The Dimensional Clinical Personality Inventorywhatamjohnbny50% (2)

- Psychodiagnostics Lab RecordsDocumento132 paginePsychodiagnostics Lab Recordsdhanpati sahu100% (1)

- Personality Disorder Intro SampleDocumento17 paginePersonality Disorder Intro SampleCess NardoNessuna valutazione finora

- Advances in Experimental Clinical Psychology: Pergamon General Psychology SeriesDa EverandAdvances in Experimental Clinical Psychology: Pergamon General Psychology SeriesNessuna valutazione finora

- California Psychological Inventory (CPI) : Click Here Click HereDocumento2 pagineCalifornia Psychological Inventory (CPI) : Click Here Click HereSana SajidNessuna valutazione finora

- Anomalous Experiences and Paranormal AttDocumento24 pagineAnomalous Experiences and Paranormal AttGustavo Gabriel CiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Psycho Dynamic Psychotherapy For Personality DisordersDocumento40 paginePsycho Dynamic Psychotherapy For Personality Disorderslhasnia100% (1)

- Art 3A10.1007 2Fs10862 011 9224 yDocumento8 pagineArt 3A10.1007 2Fs10862 011 9224 yastrimentariNessuna valutazione finora

- Sexual Orientation and Psychodynamic Psychotherapy: Sexual Science and Clinical PracticeDa EverandSexual Orientation and Psychodynamic Psychotherapy: Sexual Science and Clinical PracticeValutazione: 2 su 5 stelle2/5 (2)

- Criminal Justice and Behavior 2008 Walters 1459 83Documento26 pagineCriminal Justice and Behavior 2008 Walters 1459 83Mafalda SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- Subcomponents of Psychopathy Have Opposing Correlations With Punishment JudgmentsDocumento22 pagineSubcomponents of Psychopathy Have Opposing Correlations With Punishment JudgmentsnimadupaNessuna valutazione finora

- Skodol Et Al 2011 Part IIDocumento18 pagineSkodol Et Al 2011 Part IIssanagavNessuna valutazione finora

- The Brief Core Schema Scales (BCSS) : Psychometric Properties and Associations With Paranoia and Grandiosity in Non-Clinical and Psychosis SamplesDocumento12 pagineThe Brief Core Schema Scales (BCSS) : Psychometric Properties and Associations With Paranoia and Grandiosity in Non-Clinical and Psychosis SamplesEduardo BrentanoNessuna valutazione finora

- Qualitative Research Methods for Psychologists: Introduction through Empirical StudiesDa EverandQualitative Research Methods for Psychologists: Introduction through Empirical StudiesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (4)

- The Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale: A Comparison of The Psychometric Properties of Self-Report and Clinician-Administered FormatsDocumento11 pagineThe Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale: A Comparison of The Psychometric Properties of Self-Report and Clinician-Administered FormatsAndreea OniceanuNessuna valutazione finora

- Running Head: Adaptive Traits Associated With PsychopathyDocumento44 pagineRunning Head: Adaptive Traits Associated With PsychopathyMira MNessuna valutazione finora

- Week 5 Journal Assignment AshfordDocumento7 pagineWeek 5 Journal Assignment AshfordLUC1F3RNessuna valutazione finora

- Literature Review of Effective Treatment For Dissociative Identity DisorderDocumento7 pagineLiterature Review of Effective Treatment For Dissociative Identity Disorderc5t6h1q5Nessuna valutazione finora

- A Five-Factor Model of Psychosis With The Mmpi-2-RfDocumento49 pagineA Five-Factor Model of Psychosis With The Mmpi-2-RfskafonNessuna valutazione finora

- Bell 2010Documento8 pagineBell 2010RosarioBengocheaSecoNessuna valutazione finora

- Personality and Individual DifferencesDocumento9 paginePersonality and Individual Differenceslailatul fadhilahNessuna valutazione finora

- 12 The Clinician's Illusion and Benign Psychosis: Mike JacksonDocumento20 pagine12 The Clinician's Illusion and Benign Psychosis: Mike JacksonJosé Eduardo PorcherNessuna valutazione finora

- Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment: Lori J. Ducharme, PH.D., Redonna K. Chandler, PH.D., Alex H.S. Harris, PH.DDocumento9 pagineJournal of Substance Abuse Treatment: Lori J. Ducharme, PH.D., Redonna K. Chandler, PH.D., Alex H.S. Harris, PH.DCorina IcaNessuna valutazione finora

- ETC Webinar Communication Styles AssessmentDocumento5 pagineETC Webinar Communication Styles AssessmentCorina IcaNessuna valutazione finora

- Healthy PersonalityDocumento15 pagineHealthy PersonalityCorina IcaNessuna valutazione finora

- Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 34: Brief Interventions and Brief Therapies For Substance AbuseDocumento292 pagineTreatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 34: Brief Interventions and Brief Therapies For Substance AbuseCorina IcaNessuna valutazione finora

- Sadam ProfilDocumento28 pagineSadam ProfilCorina IcaNessuna valutazione finora

- Homicide Studies 2011 Nivette 103 31Documento30 pagineHomicide Studies 2011 Nivette 103 31Corina IcaNessuna valutazione finora

- Criminal Justice and Behavior 2013 Mokros 1397 412Documento17 pagineCriminal Justice and Behavior 2013 Mokros 1397 412Corina IcaNessuna valutazione finora

- Training Course Factsheet OPQ Level BDocumento2 pagineTraining Course Factsheet OPQ Level BCorina IcaNessuna valutazione finora

- Training Course Factsheet Personality and Ability AssessmentDocumento2 pagineTraining Course Factsheet Personality and Ability AssessmentCorina IcaNessuna valutazione finora

- OD Diagnosis: J. Michael Sammanasu JIMDocumento34 pagineOD Diagnosis: J. Michael Sammanasu JIMCorina IcaNessuna valutazione finora

- Utrecht ScaleDocumento58 pagineUtrecht ScaleMaya CamarasuNessuna valutazione finora

- Best Practice in Integrated Talent ManagementDocumento30 pagineBest Practice in Integrated Talent ManagementCorina Ica100% (2)

- Construct ValidityDocumento20 pagineConstruct ValidityCorina IcaNessuna valutazione finora

- 3D Paper StructureDocumento6 pagine3D Paper StructureCorina IcaNessuna valutazione finora

- Research DraftDocumento9 pagineResearch DraftDave CangayaoNessuna valutazione finora

- Fhhm1012 Critical ThinkingDocumento4 pagineFhhm1012 Critical Thinkingckw3650zaiNessuna valutazione finora

- Health 8: I. Multiple Choice. Write The Letter of The Correct Answer in Your PaperDocumento1 paginaHealth 8: I. Multiple Choice. Write The Letter of The Correct Answer in Your PaperAbegail Pajarillo100% (2)

- Self-Learning Home Task (SLHT) Subject: Media & Information Grade: 12 Quarter: 3 Week: 1 Name: - Section: - DateDocumento4 pagineSelf-Learning Home Task (SLHT) Subject: Media & Information Grade: 12 Quarter: 3 Week: 1 Name: - Section: - DateLaurence Anthony MercadoNessuna valutazione finora

- Local and Global CommunicationDocumento20 pagineLocal and Global CommunicationLauro EspirituNessuna valutazione finora

- Pev 114Documento2 paginePev 114Srujan ReddyNessuna valutazione finora

- PMP Intro Sample Exam QuestionsDocumento3 paginePMP Intro Sample Exam QuestionsJohn WakefieldNessuna valutazione finora

- Dalda & Amitabh-Culture, Context and Category: Dr. Kanwal KapilDocumento5 pagineDalda & Amitabh-Culture, Context and Category: Dr. Kanwal Kapilyashi mittalNessuna valutazione finora

- Quebec User Evaluation of Satisfaction With Assistive TechnologyDocumento5 pagineQuebec User Evaluation of Satisfaction With Assistive TechnologyYeison UrregoNessuna valutazione finora

- Psychological Impact in Chinua Achebe's Things Fall Apart RevisiDocumento9 paginePsychological Impact in Chinua Achebe's Things Fall Apart RevisiEmier ZulhilmiNessuna valutazione finora

- The First Consumer Action Forum - Mental Health in Sri LankaDocumento11 pagineThe First Consumer Action Forum - Mental Health in Sri LankaChintha Janaki MunasingheNessuna valutazione finora

- Neil D. Brown - Ending The Parent-Teen Control Battle - Resolve The Power Struggle and Build Trust, Responsibility, and Respect-New Harbinger Publications (2016) PDFDocumento197 pagineNeil D. Brown - Ending The Parent-Teen Control Battle - Resolve The Power Struggle and Build Trust, Responsibility, and Respect-New Harbinger Publications (2016) PDFNathaly Lemus Moreno100% (5)

- Detailed Lesson Plan in ARTs 4Documento5 pagineDetailed Lesson Plan in ARTs 4Bite CoinNessuna valutazione finora

- Group3 FinalPaperDocumento33 pagineGroup3 FinalPaperJen Patrize Cruz De GuzmanNessuna valutazione finora

- Ugp Unit On College Admission EssaysDocumento3 pagineUgp Unit On College Admission Essaysapi-334004109Nessuna valutazione finora

- BA7108 Written CommunicationDocumento5 pagineBA7108 Written CommunicationamanNessuna valutazione finora

- Adapted, Simplified Way To Explain A Schema and A Mode Mode-Modell For Children Integration of The Family: Which Schemata Do Exist?Documento1 paginaAdapted, Simplified Way To Explain A Schema and A Mode Mode-Modell For Children Integration of The Family: Which Schemata Do Exist?mina mirNessuna valutazione finora

- Leadership: 1. Who Are Leaders and What Is LeadershipDocumento10 pagineLeadership: 1. Who Are Leaders and What Is Leadershiphien cungNessuna valutazione finora

- TTL 2 Module 4 APPLICATIONDocumento2 pagineTTL 2 Module 4 APPLICATIONHelna Cachila100% (1)

- Mudre, LilyDocumento45 pagineMudre, LilyARNessuna valutazione finora

- Grade 3 Idioms 2Documento2 pagineGrade 3 Idioms 2Krystal Grace D. PaduraNessuna valutazione finora

- Torg Eternity - Kadandra - USDocumento3 pagineTorg Eternity - Kadandra - USZarotachak100% (2)

- Chapter 8 - Infant Reflexes and Developmental Milestones - SCDocumento30 pagineChapter 8 - Infant Reflexes and Developmental Milestones - SCIbraheem MohdNessuna valutazione finora

- Research 3rd QuarterDocumento10 pagineResearch 3rd QuarterMaybell GonzalesNessuna valutazione finora

- CommLab-India-eLearning-Design-and-the-Right-Brain 2Documento46 pagineCommLab-India-eLearning-Design-and-the-Right-Brain 2Cancer CaneNessuna valutazione finora

- Symbolic Frame WorksheetDocumento3 pagineSymbolic Frame Worksheetapi-556537858Nessuna valutazione finora

- IPCC Visual Style Guide PDFDocumento28 pagineIPCC Visual Style Guide PDFSarthak P. ThakurNessuna valutazione finora

- An Introduction To KammaDocumento22 pagineAn Introduction To KammasumangalaNessuna valutazione finora

- Advances in REBT - Bernard & DrydenDocumento391 pagineAdvances in REBT - Bernard & DrydenAngela Ramos100% (1)

- Case Analysis On Suicide - A Study On SociologyDocumento2 pagineCase Analysis On Suicide - A Study On SociologyBriar Rose BausingNessuna valutazione finora