Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Acoustemology Indigeneity and Joik in

Caricato da

Adel WangCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Acoustemology Indigeneity and Joik in

Caricato da

Adel WangCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Acoustemology, Indigeneity, and Joik in Valkeap's Symphonic Activism: Views from

Europe's Arctic Fringes for Environmental Ethnomusicology

Author(s): Tina K. Ramnarine

Source: Ethnomusicology, Vol. 53, No. 2 (SPRING/SUMMER 2009), pp. 187-217

Published by: University of Illinois Press on behalf of Society for Ethnomusicology

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25653066 .

Accessed: 13/02/2015 02:06

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

University of Illinois Press and Society for Ethnomusicology are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve

and extend access to Ethnomusicology.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 132.235.61.22 on Fri, 13 Feb 2015 02:06:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Vol.

No.

53,

Ethnomusicology

2009

Spring/Summer

Indigeneity, and Joik

Acoustemology,

in Valkeapaa's

Symphonic Activism:

Arctic Fringes

from Europe's

Views

Environmental

Ethnomusicoiogy

Tina K. Ramnarine

Can

you hear

/ Royal Holloway

the sound

for

University of London

of life

in the roaring of the creek

in the blowing of thewind

That is all Iwant

that is all

to say

(1943-2001), published in his volume

poem, by NilsAslakValkeapaa

the

Wind

([1974,1976,1981]

1985), resonates with eth

This Trekways of

to

attention

acoustic

nomusicological

ecologies, to analyses of theways in

which

poem

environments

can

be

shape musical

interpreted

as

concepts

a statement,

drawing

and creative processes.

a

listener's

attention

The

to a

sound-producing environment. It can be read as a question about perception:

"can you hear the sound of life?"Or it can be understood as an assertion of

authorship thatmoves beyond mere production of a literary text, as the au

thor's intention to say "the roaring of the creek," "the blowing of thewind."

Authorship in this sense draws on Murray Schafer's ideas first presented in

the 1970s about not only trying to hear the acoustic environment as amusical

composition but also owning responsibility for its composition (1977:205).

In ethnomusicoiogy these ideas have been elaborated with nuances from the

turn.Feld,for example, writes about acoustic

discipline's phenomenological

epistemologies, using the term "acoustemology" as "a special kind of know

ing" inwhich "sonic sensibility is basic to experiential truth" (1994:11).

This article discusses acoustic epistemologies and sonic environments in

themusical and political worlds of the Sami,who are positioned as indigenous

2009 by the Society for Ethnomusicoiogy

This content downloaded from 132.235.61.22 on Fri, 13 Feb 2015 02:06:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

188

Ethnomusicology,

Spring/Summer

2009

people on the Arctic fringes of Europe, living across the Nordic countries

and the Russian Kola Peninsula, an area which the Sami call Sapmi, land of

the Sami. I focus on thejoik, a vocal genre characterized by distinctive vocal

some

timbres and techniques, inwhich the performer joiks (sings?though

commentators distinguish between "joiking" and "singing") something rather

than joiks about something. I explore joik as itappears in the symphonic tra

dition through a specific case study?Valkeapaa's

symphonic activism.While

Valkeapaa's symphonic projects and his statuswithin Sapmi and beyond lend

themselves to the pursuit of various critical strandswithin ethnomusicologi

cal discourses on the individual and thework, the discussion in this article is

framed by broad questions concerning creativity,environment, and activism.

What does itmean to joik something rather than to joik about something?

What is authorship when the author, themusical form,and itsobject are one

and the same (the joiker-joik-joiked complex)? As the North Pole melts, why

should we consider sonic sensibilities?What are the political implications of

In choosing to examine

posing such questions about Sami acoustemologies?

how joik has been featured in the symphonic tradition ofWestern artmusic,

referring to two symphonies composed in the 1990s?the Joik Symphony

and the Bird Symphony?my

project is to explore authorship, politics, and

environment in the acoustemologies of northern Europe's fringes,pointing

to an indigenous politics that is not based solely on affirming the joik as a

genre that is one of themost recognizably identified as Sami, but also on the

engagement with and reconfiguration of amusical aesthetic?the

symphonic

tradition?that tells us something about musical creativity,political expres

sions, and environmental concerns, such that the symphony, aswell as the joik,

can be understood within the frameworks of an environmental ethnomusi

cology. I draw initiallyon theoretical frameworks from acoustic ecology that

encourage us to attend to sound in ecological thought. But creative processes

explained only in terms of the sonic environment as mediating human/nature

relations or as shaping musical conceptualizations render incomplete insights

into an understanding of how joik singers sing something. I also turn,therefore,

to theoretical ideas that have been developed in green postcolonial studies

regarding colonial impacts on ecosystems and thinking past the human.

"All of a sudden

people

saw

Joik and the Complexities

a ptarmigan":

of Relationality

Sami have been the subject of considerable ethnographic attention since

in earlier accounts;

the seventeenth century and they are also mentioned

one of the earliest references ismade by Tacitus in the firstcentury ce. They

are traditionally known as nomadic pastoralists with a reindeer economy,

though different Sami populations have been engaged in a variety of subsis

This content downloaded from 132.235.61.22 on Fri, 13 Feb 2015 02:06:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Arctic Fringes and Ethnomusicoiogy

Ramnarine:

189

tence economies and identify themselves as forest,mountain, or coastal Sami,

depending on their primary subsistence modes. Despite the image of the

nomadic reindeer herder, only a minority are occupied now with reindeer

and today all Sami have fixed housing as well. Sami languages are related to

Finnish, belonging to the Finno-Ugric linguistic group. Due to state education

policies, however, many Sami have grown up speaking Norwegian, Swedish,

Finnish, or Russian as theirprincipal languages instead. A modern movement

to reclaim Sami languages has been fostered, especially through school educa

tion

systems.

The Sami across different regions use a variety of terms for singing and

vuolle.

The south

son& 'mc\udm%

joikjuoi'ga

Sami use the terms vuollie and vuolle. The northern Sami use the terms luohti

(for the song) and juoigan (to sing). In the eastern regions, the terms leu'dd

and ly'vvt are used. The term joik (or yoik) appears widely in the research

literature as a general term to indicate both the song and the singing.

Joikwas often associated with shamanism, the earliest description of

which was recorded in the twelfth century in theHistoria Norwegiae

(Tol

ley 2009:14), and even today "sacral understandings" of joik persist, with joik

seen as having the "power to encompass and express" the reindeer, the bear,

or the person referred to and recalled in the joik (DuBois 2006:71). Edstrom

notes that inpre-Christian Scandinavia, shamans were thought to receive their

joiks from supernatural beings (1985:160). Joiks are performed for animals

and land as well as for people. Joik performance thus points to a complex

set of relationships between music, environment, and the sacred, and con

temporary joik practices provide a rich forum for exploring the intersections

between acoustic epistemologies and indigenous politics. Inwriting about

relationships and intersections, however, I have pointed to several assump

tions about joik that demand furthercritical scrutiny.The notion of relation

ship ishabitually evoked in definitions of acoustic ecology. The World Forum

forAcoustic Ecology, for example, defines its area of enquiry as focusing on

"the

inter-relationship

between

sound,

nature,

and

society"

in their

statement

of rationale printed in the front pages of the society's journal, SoundScape:

The Journal of Acoustic Ecology. Furthermore, in the editorial to the first

volume of this journalWesterkamp states the concerns of acoustic ecology

as both the "relationship between soundscape and listener" and "how the

nature of this relationship makes out the character of any given soundscape"

thereby putting acoustic phenomena at "the centre of ecological thinking"

(Westerkamp 2000:4). The possibility thatperformance might generate new

understandings of nature-human relations has become a theoretical interest in

the social sciences, also, opening spaces for thinking about acoustic-musical

activities and prompting a performative turn that views nature performed

by human and nonhuman

agents in creative, improvisatory, and emergent

This content downloaded from 132.235.61.22 on Fri, 13 Feb 2015 02:06:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

190

Ethnomusicology,

Spring/Summer

2009

2003:4). In capturing Sami sonic

processes (Szerszynski,Heim,andWaterton

environments, modern joik recordings sometimes include birdsong and rein

deer sounds: soundscapes, therefore, that take us into debates on ecological

thought and nature performed.1 If the relationship between acoustics and

ecologies opens spaces for critical thinking on human agency, so too do the

intersections between acoustic epistemologies and indigenous politics. As

the theme of symphonic activism is developed Imove away from the idea

of intersections as denoting points of coincidence

towards highlighting an

understanding of acoustic phenomena that is already politicized. In this re

spect, discourses on and theorization of joiking something provide a point

of departure.

Joiking something is a concept thatvarious researchers have struggled to

explain. In his ethnographic study of the Sami of the Russian Kola Peninsula

published in 1946, Nikolai NikolaevichVolkov wrote that Sami songs "do not

have

any artistic

images.

The

songs

are

improvisations

with

a concrete

theme.

To 'create' a song, the Sami have to put their attention on some outstanding

event in their life.Then they 'create' a song and sing it"(in Lasko andTaksami

does

1996:90). A joik singer tellsVolkov that the joik syllabalization "ly-ly-ly"

not mean anything; it is used "to fly into a song" (ibid.). Edstrom refers to

melody as a fundamentally significant element of joik throughwhich, accord

ing to Sami concepts, the joiker can express an opinion on the qualities of

the object of the joik (for example, a person), one's feelings for the object of

the joik, and memories of the object that isbeing joiked (Edstrom 1985:161).

The Swedish joik collector Karl Tiren, who recorded around 700 joiks and

transcribed over 500 of them, describes joiking something by referring to

the concept of leitmotif in theWagnerian tradition. Joik becomes an example

of tonmalerei (tone painting) (Tiren 1942). But tonmalerei ismerely evoca

tive or imitative and indicates distance between the signifier and signified,

inwhich the latter is represented through a musical label. The problems of

thinking about music as having narrative, representational and programmatic

qualities are compounded ifapplied to joik since musical representation does

not correspond to the concept of joiking something. Ola Graff (2004) takes

tonmalerei as a point of departure but questions whether it is a characteristic

of all joikmelodies as well as whether all joiks have a concrete referential

object. Graff adopts a semiotic approach to the relation between joik and its

object, distinguishing between music as structure and music as communica

tion. For him, the joik-object relation is initially an arbitrary one, just as the

name of a person could have been chosen frommany other possibilities, but

itbecomes an iconic relation, inwhich the joik serves a referential (or repre

sentational) function. Such referentiality is elaborated through body gesture

inperformance and through language: including storytelling associated with

a joik, textual ambiguity (where one word may have several meanings), and

This content downloaded from 132.235.61.22 on Fri, 13 Feb 2015 02:06:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Ramnarine:

Arctic Fringes and Ethnomusicoiogy

191

the borrowing of other texts resulting in an intertextual joik.Graff (2004 and

p.c, 28 January 2OO8,Troms0, Norway) argues that inview of such performa

tive and narrative strategies, a joik can take on new meanings, seeming to

refer to other objects, but the basic referentialmeaning ispresent whether or

not it isperceived by a listener. Thus, the transmission ofmeaning is divided

and multilayered and it is possible to present differentmeanings across the

various

layers

of denotation,

connotation,

textual

ambiguity,

and

gesture.

I suggest that both tonmalerei and semiotics are theoretical frameswithin

discourses on musical representation throughwhich attempts to understand

the concept of joiking something are made. They are frames involving pro

cesses of translation throughwhich joik concepts might be grasped. But they

are also modes of thinking throughwhich joik significance and meaning may

be obscured. Joiking something may not be reducible to thinking about mu

sic's capacity to refer to something beyond itself.Per Haetta, the joikerwith

whom Ola Graffworked extensively, spoke about joik personifying, illustrat

ing,or taking themelodic likeness of its object, and the joiker Ante Mihkkal

Gaup fromKautokeino (Norway) told Graff that "a joik isyour deepest name"

(p.c, Graff, 28 January 2OO8,Troms0, Norway). The joiker and lawyer Ande

Somby explains that an important technical and aesthetic aspect of joik is:

into the room that is not there before you start,

ability to bring something

like I did with

I had heard].

the ptarmigan

[referring to a recent performance

saw a ptarmigan

as

All of a sudden

and right after I brought

in a wolf

people

well. Not a very hard wolf, but still a wolf; and that is close

to the old shamanistic

The

... In that

way your listeners can turn into a grouse bird

a

for

and then you can hope

that they have a taste of

[the ptarmigan]

moment,

this notion

of transforming

and what

it has a lot of ethical

that means,

because

idea of transformation

consequences.

(Interview,

Ande

Somby,

25 January

2OO8,Troms0,

Norway)

The discourses of these joikers seem removed from analytical perspec

tives on the symphony.Yet,my attempts to reconcile joik and symphonic con

cepts, to explain one mode through the other, are pertinent to this exploration

of Valkeapaa's

symphonic activism for they involve shifts in fundamental

concepts around issues ofmusical value, creativity,and relationality (whether

forgenre, environment, or politics). Modern joik performers (solo artists and

groups) like Ande Somby,Mari Boine, Wimme Saari, Frode Fjellheim, Johan

Sara,Tiina Sanila, Amoc, Ulla Pirttijarvi, Adjagas, and Angelin Tytot (Girls of

Angeli), as well as Nils-Aslak Valkeapaa himself, have turned our attention to

theways inwhich commercial recordings, media technologies, and global

music markets have been used inpromoting indigenous politics and forming

global indigenous sensibilities. In choosing symphonic projects, I intend to

highlight how the symphony has also featured in the indigenous project. In

symphonic projects aswell as in some contemporary joik recordings inspired

by rock, rap, or heavy metal we find Sami musicians offering a critique of

This content downloaded from 132.235.61.22 on Fri, 13 Feb 2015 02:06:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

192

Ethnomusicology,

Spring/Summer

2009

environmental thinking that insists on the notion of relationship between

humans and their environments, and of sound mediating between them.

This critique is a fundamental aspect of these Nordic Arctic acoustemolo

gies. It is a critique thatmight contribute significant insights to research

in environmental ethnomusicology. Indeed, if creativity, poli

perspectives

are themes that take us into seemingly familiar and

and

environment

tics,

divisive configurations of the cultural, the social, and the natural, adopted

by ethnographic disciplines as well as by acoustic ecology, Sami indigenous

political and musical expressions might offer interesting alternatives to ques

tions about music in the nexus of nature/human relations that cut across

in the symphonic tradition con

culture, society, and nature. Acoustemology

sidered here might challenge our ideas of relationality altogether, dissolving

the constructs throughwhich a relationship between humans and nature (or

seems tomake

between cultural behavior and environmental phenomena)

sense. Such acoustic epistemologies

at

lie

the heart of indigenous political

agendas. They underpin notions of place and home. In attending to the ana

lytical challenges posed by joik that have preoccupied

joik researchers, my

aim is to highlight how Nordic Arctic acoustemologies

provide important

perspectives on environmental issues in both global and local terms (for

instance on current concerns about the sustainable development of Arctic

resources).

Introducing

the Protagonist

Nils-Aslak Valkeapaa, the Sami composer, writer, visual artist, and activist

who became such an influential and important figure in the Sami indigenous

movement from the 1970s onwards, is an ideal protagonist in exploring acous

temology and indigenous politics in the symphonic tradition.He was born in

Enontekio, innorthern Finland, and lived inboth Finland and Norway, crossing

the nation-state borders that divide Sapmi. He was active in theWorld Council

of Indigenous Peoples, composed music for the filmOfelas (Pathfinder,directed

by Nils Gaup, 1987), and received several awards for his work. He is now an

iconic figure in the Sami artistic and political world. As Gaski observed in a

in 2001: "Nils-Aslak's accomplishments forhis people were so

come

to be regarded by all posterity as amodern-day mythical

that

he

will

great

Sami"

the

(Gaski 2001).Valkeapaa played an extraordinary role in

being among

movement from the late 1960s onwards. He engaged

the

revival

fostering

joik

inmusical experiments and collaborations that have resulted in shifting joik

transmission and performance patterns. Although his innovations also received

some criticism, his legacy is apparent in the presentation of joik in popular

music (in rock, heavy metal, and rap), in the symphony, in themusic video, in

Sami music festivals, in choral projects, and in school music education.2 It is

commemoration

This content downloaded from 132.235.61.22 on Fri, 13 Feb 2015 02:06:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Ramnarine:

Arctic Fringes and Ethnomusicoiogy

193

apparent too in the development of contemporary Sami literature,film, and in

the establishment of a contemporary Sami theater group and the publishing

house,DAT. He was awarded theNordic Prize forLiterature in 1991 forBeaivi,

Ahcdzan (The Sun, My Father), the jury's special prize in the European Radio

Competition Prix Italia in 1993 forGoase DuSse, (Bird symphony), and he was

invited to perform joik at the opening ceremony of theOlympic Winter Games

inNorway

Through Valkeapaa's works we gain a better understanding of the connect

edness of joiking, story-telling,painting, and photography As Stoor notes, story

telling,pauses, and song are all part of the joik composition (Stoor 2007:237).

Textual codes and visual representations are a fundamental aspect of this kind

of acoustemology. In fact,Valkeapaa's "many-leveled linguistic play" offersways

of approaching "double layers of communication" in joik and in storytelling

(Gaski 1997:211-15). Questions about musical meaning, tone painting and

referentiality in joik arise in relation to linguistic frames thatmight be impos

sible to translate. Gaski indicates some of the difficulties, noting that there is

an enormous Sami vocabulary for describing reindeer and around 150 terms

to identify different kinds of snow. The problems of translating a minority

language like Sami lay bare the limitations ofmajority languages, a revelation

throughwhich poems, stories, images, and joiks become politicized

ing to differentways of viewing theworld (cf.,Gaski 1997).

Joiks

in the Western

inpoint

Art Tradition

Valkeapaa was not the first to introduce use of the joik in theWestern

art tradition. The joik based artwork emerged in the early twentieth century,

(1917) by the Finnish

notably with a symphonic poem Aslak Smaukka

an

Hetta

Leevi

and

Aslak

(1930), by the Finnish

opera,

composer

Madetoja,

The Lapplands

joik collector and researcher Armas Launis (1884-1959).

the

Swedish

Wilhelm

composer

Peterson-Berger, firstperformed

symfoni by

in 1917, was based on joiks recorded by KarlTiren. (Peterson-Berger also

wrote the introduction toTiren's thesis [1942].) The first such joik based

artwork may be Lappisk Juoige-Marsch, the unpublished manuscript of the

Norwegian composer Ole Olsen (Graff 1997:36). Einar Englund used joiks in

the soundtrack to an award winning film at Cannes, Valkoinen Peura (The

White Reindeer, 1952). The joik has also featured in choral works, including

(1975) by Erik Bergman.

Lapponia

More recent joik based artworks include Frode Fjellheim's mass, Aejlies

Arctic Mass,

1995) and Skuvle Nelja (an

Gaaltije (The Sacred Source?an

in

in

that

Sweden

Ostersund,

opera

2006), and Jan Sandstrom's

premiered

choral work Biegga Luohte (Ybik to the mountain wind) formixed choir,

premiered in London in 1998.3 Drawing on different traditions of sacred music,

This content downloaded from 132.235.61.22 on Fri, 13 Feb 2015 02:06:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

194

Ethnomusicology,

Spring/Summer

2009

?)d\heirtisAejlies Gaaltije is based on the South Sami liturgybut juxtaposes

Christian and Shaman belief systems throughmovements such as the "kyjrie"

(kyrie),"aejlies, aejlies, aejlies" (sanctus),"Jubmelen vuelie" (Joik of God, based

on a joik transcribed by KarlTiren),andMTjaehkere"(a movement thatpresents

a joik referring to the sacred mountain Tjaehkere). Johan Sara composed a

Sami opera, Skuolft, in 2005 and the Sdmiska Romanza

(Sami romance) for

in

2000.

and

With

the

chamber choir

orchestra

exceptions of Fjellheim and

were

the

members

of the Sami Society of

who

both

Sara,

amongst

founding

in

the

March

mid-1990s (interview, Sara, 25

2008, Maze, Norway),

Composers

these are examples of joik based artworks by non-Sami composers. Several of

these composers have referred to the ethnographic recordings, transcriptions,

and research writings of scholars who worked across theNordic region in the

early twentieth century, including: Vaino Salminen (18 joiks recorded in the

Torne Lappmark area in 1906-1907); Armas Launis (1904 and 1905 record

ings, transcriptions and field diaries, see Launis [1904-05] 2004); Karl Tiren

(whose recordings dating from 1911 were lost in their transfer to Berlin in

the 1930s, though he retained some for his personal collection [seeTernhag

2000; Jones-Bamman 2003]); Elial Lagercrantz (recordings and transcriptions

of joiks fromVarangerbotn, Norway, see Figure 1); and Armas Otto Vaisanen.

InNils-Aslak Valkeapaa's symphonic work, the joik is introduced as an aspect

of symphonic thought but he also used the genre of symphony to throw no

tions of creativity, authorship, and form into question. The two symphonies

discussed below present rather different approaches to the incorporation and

treatment of joik. They also present different kinds of responses to political

concerns during this period.

"Reshaped

in my

soul":

The Joik

Symphony

In 1973, Nils-Aslak Valkeapaa had invited the folk revivalists and jazz

musicians, Seppo Paakkunainen,Ilpo Saastamoinen, and Esko Rosnell to go to

Adja Johki. In this northern Finnish location they experimented with adding

instrumental accompaniment

(of flute, acoustic guitar, and bongo) to joiks.

In 1980, having listened to Dvorak's Ninth Symphony, inwhich the com

poser had drawn upon the spirituals ofAfrican-Americans, Valkeapaa asked

Paakkunainen (b. 1943) ifhe would compose something similar based on

Sami joiks. His request tapped into the expressive politics ofminorities and

strengthened a musical collaboration that had begun in 1971 and that had

hitherto resulted invarious jazz-joik experiments (e.g.,Valkeapaa 1998). The

resulting symphony (the second version ofwhich was completed in 1989),

(Joik symphony) is scored for a symphony orchestra,

theJuoigansinfoniija

instrumental

group, two solo joik singers and solo saxophone,

improvising

a scoring that Paakkunainen repeated in a later suite for symphony orches

This content downloaded from 132.235.61.22 on Fri, 13 Feb 2015 02:06:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Ramnarine:

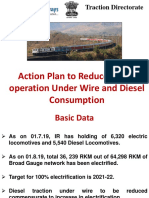

Figure

1. Elial

Lagercrantz

graph by Henrik Nilssen,

the Varangerbotn

Samiske

Arctic Fringes and Ethnomusicoiogy

recording

the Sami

musician,

Movs-Niillas.

195

Photo

1920 or 1925. Reproduced with permission from

Museum.

*^

v lt;>" *

iiffiillli

tra based on Nils-Aslak Valkeapaa's melodies and poems Sdpmi Lottdzan

(both works were recorded in 1992.) There are fourmovements (parts) in

theJoik Symphony :(1) "Gumadii galbmasit skabma" (Polar night resound

ingwith cold); (2) "Humadii, duoddarat juige" (Drone, joik of the hills); (3)

"Oappat, vieljat vaimmustan, biegga" (Sisters, brothers, thewind inmy heart);

and (4) "Eallima ahpi" (The ocean of life). Around twenty joiks are featured

in the symphony, the melodic outlines of which are presented in various

timbral combinations throughout thework (see Figure 2). Traditional joiks,

Valkeapaa's newly composed joiks, and three of his personal joiks appear in

the symphony (email, Seppo Paakkunainen, 8 March 2008).

Some commentators have described this symphony as an example of

musical fusion (e.g., Muikku 1989).Valkeapaa wrote about joiks in thiswork

as being "a sea of hills"; this symphony is:"Hills.Yoiking. The Sun. And Baron

[Paakkunainen], too" (the final lines in his poem in the liner notes [1992:19]).

Seppo Paakkunainen writes in the same liner notes to the recording of the

Joik Symphony that "this is theway the luodit [joiks] I have learned by ear

This content downloaded from 132.235.61.22 on Fri, 13 Feb 2015 02:06:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

196

Ethnomusicology,

Spring/Summer

2009

fromAim [Nils-AslakValkeapaa] have been reshaped inmy soul" (1992:8).

Itwas composed for the performers who recorded the symphony and the

joikers are Valkeapaa and Johan Anders Baer. Paakkunainen plays the saxo

phone and his Finnish folk revival group, Karelia, play the improvising in

strumental parts. Paakkunainen aims to "transfer on to paper what he has

discovered through improvisation" (cited inMuikku 1989:47), a stance that

reveals composition as a process that is generated through performance.

Paakkunainen's discourse alerts us that composer-performer distinctions are

not wholly appropriate in analyzing theJoik Symphony This is a point that

is also relevant to the Bird Symphony. These are works that are based on

overlapping complexes of environmental acoustic phenomena, improvisa

tion, and formal structural organization, realized through unpredictable sonic

utterances inwhich not only the roles of composer and performer merge

but inwhich human sonic production is situated within specific acoustic

soundscapes. The works are only realized in performance.

Moreover, in traditional joik performance the notion of composer is not

prominent. Graff notes that listeners do not usually ask "who is the com

poser?" They are more likely to ask "To whom belongs the joik?" In his

fieldwork on the surviving 18 joiks of a coastal Sami community, he received

different responses about the composer of each joik. Often, commentators

guessed that the person joiked (the object of the joik) might have been the

composer, but in his sample none of the joiks had actually been composed

by that referenced (joiked) person. Only in three or four of those joiks did

Graff have reason to believe that the composer was known, though it seemed

likely that in general people having a relation to the person referenced in a

and p.c, 28 January

joikwere the most likely authors (Graff 2004:182-83,

2OO8,Troms0, Norway).

Seppo Paakkunainen noted that theJoik Symphony was composed "hand

in hand" with Valkeapaa, with whom he stayed in Pattikka during part of the

compositional process, discussing how and where to use joiks in the sym

phony. In the formal processes of identifying a composer, a contract for the

performing right royalties stipulates both musicians as composers, though

in the CD recording information,Valkeapaa wanted only Paakkunainen to be

identified as the composer (email, Paakkunainen, 8 March 2008). That the

identification of a composer is not necessarily important in traditional joik

practice has a bearing on how we analyze the commissioning of theJoik

are

Symphony Since the joiks themselves and knowing towhom they belong

notions

of

seems

clear that, in accordance with traditional

joik

important it

to

ownership, Valkeapaa intended the resulting symphonic work "to belong"

we

can

concern.

a

"the Sami." Authorship is secondary

How, then,

interpret

theJoik Symphony?

Some responses might be formulated in considering the pan-Sami po

liticalmovement that has seen Sami as oppressed minorities under the ban

This content downloaded from 132.235.61.22 on Fri, 13 Feb 2015 02:06:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Ramnarine:

Arctic Fringes and Ethnomusicoiogy

197

ner of the "FourthWorld," and of which Valkeapaa was an

from the 1970s until his death in 2001. My firstencounter

Sami indigenous political movement was in June 1992 as

out fieldwork in Finland on globalization processes, creative

active member

with this pan

Iwas carrying

choices, revival

in

and

nationalist

sensibilities

Finnish

folkmusic.

discourses,

contemporary

Sami representatives arrived inHelsinki to discuss their position in a chang

ing Europe, including negotiations for Sami self-government. The political

discussions were followed by Sami joik and drum performances, highlight

ing those elements?song,

language, and shamanistic belief?that had once

Inmy current Arctic fieldwork

been suppressed (Ramnarine 2003:181-84).

encounters, the trends are towards a pan-Sami sensibility that is neverthe

less characterized by articulation of diverse political views. Pan-Saminess is

contextualized within various institutional frameworks (academic and politi

cal) that support debate, as well as within global networks of indigeneity, a

developing Arctic tourist industrywithin which

of

the

Sami

are

contested,

and

rounding industrial development

environmental

protection,

various

representations and artifacts

antagonisms

or

collaborations

sur

(particularly oil and gas) on one hand, and

assessment,

and monitoring

on

the other.

Joik has played a fundamental role in these processes. As an integral

part of shamanistic practice, joikwas prohibited in Christian Scandinavia,

although travellers and missionaries reported joiking from the seventeenth

to nineteenth centuries. Researchers in the early twentieth century believed

that joikingwas a disappearing tradition?a view strengthened by joik per

formance prohibitions and the negative perceptions towards joik held by

Sami themselves. The White Reindeer (the filmmentioned above towhich

Englund composed the soundtrack) reveals popular, negative perceptions of

Sami shamanism, joiking, and drumming during the 1950s. In this film,only

the female shaman (depicted as awild woman with dangerous powers) joiks

and brings forward the magic of the shaman drum. She is a danger to her

own community. Her husband kills her as she takes the form of a reindeer.

As recently as the 1970s, joiking in Finland was forbidden in some schools

and Ande Somby has noted that even in the 1990s joikingwas prohibited in

some parts of Norway (Somby 1995). Contemporary joiking is nevertheless

enjoying more widespread

popularity. In the 1940s Sami began campaign

ing for recognition as an ethnic minority. In the Sami activist movement of

the 1970s, joik performance was encouraged as a vital part of the political

indigenous project and featured in the much publicized Alta dam protests

of the late 1970s. By the beginning of the twenty-firstcentury, joik had been

transformed into amajor symbol in the Sami indigenous political movement. It

also features inmusical experimentation projects, including ones that are not

specified as Sami projects, particularly in choirs where singers are encouraged

to explore various vocal techniques. A choir performing Stories from the

North inTroms0, January 2008, included Sami drum and joiks (Johan Sara's

This content downloaded from 132.235.61.22 on Fri, 13 Feb 2015 02:06:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

198

Ethnomusicology,

Spring/Summer

2009

"The Moon?My

Sister"; Frode Fjellheim's "A Sister from the North "),as well

as extracts such as Grieg's /Himmelen

and Rachmaninov's Shestopsalmie

music

The

(from Vespers).

director, Ragnar Rasmussen, commented that it is

a challenge to adhere to the original function and intention of joik singing

within the classical frame of the chamber choir, but unconventional singing

techniques, such as belting and overtone singing are explored in the choir's

practice (p.c, 22 January 2OO8,Troms0, Norway). This was amultimedia pre

sentation with photographs of Norwegian landscapes and people displayed

on a back stage drop and commentaries on pollution from oil industries and

on

climate

change.

In requesting the incorporation of joiks into a symphony,Valkeapaa was

pointing to the value of the joik.He held the joik in the same esteem as the

symphony. In this respect, he followed Wilhelm Peterson-Berger who wrote

in the preface to the 1942 bound edition of his Lapplandssymfoni

that joik

as

to

Germanic

be

offensive

the

"naive

musical

mind," but

might

perceived

that in the joik "it is impossible to deny the impression of great artistic con

tent" (cited inGraff 1997:35). Through use of the joik as an integral part of a

symphonic texture,Valkeapaa issued a challenge to earlier representations of

Sami as musically strange or incapable. The Italian traveller,Guiseppe Acerbi

(among the firstto transcribe joikmelodies) had this to say about Sami mu

sic: "Their music, without meaning and without measure, time or rhythms

was terminated only by the totalwaste of breath; and the length of the song

depended entirely on the largeness of the stomach, and the strength of the

lungs" (Acerbi 1802:66). Even amore recent commentator, Szomjas-Schiffert,

the sympathetic Hungarian musicologist who carried out fieldwork in the

1960s, describes joik as consisting of two kinds of singing: the first is "loud,

shouting singing" with high notes resembling "shrieks," and the second is

"mumbling" (1996:64).

Yet,Valkeapaa's challenge through his practices in these kinds ofmusical

realms remains ambiguous inview of his discourse on musical difference. In

1984, he wrote:

than that. They include

Its functions are much wider

joik is not merely music.

The

To frighten the wolves.

to social contact. To calm down

the reindeers.

as art. Art requires public. The joik was

never intended

to be performed

was

joik

The

ways

Animals.

to call up friends, even enemies.

The

land and the environment.

it religious. What

about

makes

also a step to another world, which

soon obvious

it

is

that

Western

If one compares

with

its technique?

music,

joik

used

The

joik was

they are of different languages

et al., 2000:18)

Krumhansl

with

different

functions.

(Cited

and

translated

in

can be read in several ways. One interpretation is that in

this passage, Valkeapaa insists on according value to the joik just as to the

symphony (as an example of a much esteemed Western musical form)while

This discourse

This content downloaded from 132.235.61.22 on Fri, 13 Feb 2015 02:06:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Ramnarine:

Arctic Fringes and Ethnomusicoiogy

199

maintaining the unique status of Sami as indigenous people with distinc

to those of

tivemusical practices who might offer alternative worldviews

at

once

the recognition of

dominant Western discourses. The ambiguity is

marginalization and the assertion ofworth expressed in relation tomusical

difference and musical value. Indigeneity as a marker of political difference

is asserted

even

as external

representations

of Sami music

are

resisted.

At heart, this symphony was commissioned to register protest against

negative representations of Sami, and it is not accidental that Paakkunainen

should have been chosen as author of thework. Symphonic activism in the

Joik Symphony ismodelled on an earlier understanding of theways inwhich

joikmight be used as a protest song. Though located in somewhat different

in jazz and in Finnish folk-popular music

musical worlds?Paakkunainen

in

traditional

and

experiments

Valkeapaa

joik and joik-popular experiments?

interests.

also

had

shared

musical

firstrecordings, such as

they

Valkeapaa's

from

Finska

Finnish

Lapland (Joiks

Lapland, 1968) were

Joikuja/Jojk frdn

inspired by contemporary popular models, especially the urban folkmusic

of singers like Bob Dylan, though environmental sounds were later added to

counterbalance acoustic instrumentation (Jones-Bamman [2001] 2006:356),

in keeping with recordings he made of traditional joikwith accompaniment

of sounds from Sami nature in the early 1980s (Edstrom 1985:164). Urban

folkmusic models had also inspired Seppo Paakkunainen during the 1960s

In highlighting the model of

Finnish folk revival (Ramnarine 2003:58-60).

Dvorak's New World Symphony, with its reference toAfrican-American mu

sical traditions,Valkeapaa drew attention to the status of Sami as colonized

people forging global alignments with the (post)colonial world as well as

with the global indigenous movement of "FourthWorld" politics. This per

spective on the symphony also appears in his writings inwhich he drew

parallels between the colonization of Sami and African peoples drawing on

ideas presented by James Baldwin (Valkeapaa [1971] 1983:98-99,103).

Nature also appears in this discourse. The poem thatValkeapaa wrote

in connection with this symphony includes the lines:"You can see nature as

milieu,

or, then, man

as nature."

"You did not hear the bird, itwas

I": The Bird Symphony

During the 1990s, the political status of the northern fringes of Europe

changed from primarily a security and military area during the Cold War pe

riod to a potentially important geoeconomic area of international cooperation

in the globalized world economy (Heininen 2002). During thisperiod, various

Sami political organizations were established or reformulated, including the

Sami Council, the Sami Parliament and Sami representation in the councils

of the Barents Euro-Arctic Region, inwhich Sami voiced their opposition

This content downloaded from 132.235.61.22 on Fri, 13 Feb 2015 02:06:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Figure 2. Extract from the score of theJoik Symphony. Reproduced

permission from Seppo Paakkunainen.

This content downloaded from 132.235.61.22 on Fri, 13 Feb 2015 02:06:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

with

Arctic Fringes and Ethnomusicoiogy

Ramnarine:

to environmental damages

from industrialization processes

201

and their fears

neocolonialism.4

concerning

The shift in emphasis from the politics ofminority to the politics of en

vironment and economy is reflected inValkeapaa's symphonic projects. The

Bird Symphony, awarded the Prix Italia in 1993, raises different kinds of ques

tions about authorship, improvisation and musical politics. In contrast to the

Joik Symphony, the "composer" of the Bird Symphony isValkeapaa, but the

work also involves improvising agents. Four movements are indicated, using

performance directions such that the firstmovement is "Assai animato"; the

anima

second,"Con

the

cantabile";

third,"Con

fuoco";

and

the

fourth,"Largo

morendo,"but the recorded symphony plays continuously for 59 minutes and

20 seconds, and the listenermust determine when a movement begins and

ends. After 32 minutes and 2 seconds of recorded birdsong and waterscapes,

a joik singer is introduced into themusical texture and is eventually joined

by a second singer (singing a countermelody). The singers are preceded by

reindeer bells. The joik gives way to the bird soundscape until the final stages

of the symphony when it is repeated, first of all as iffrom a distance, gaining

prominence, and once again giving way to the birdsongs towards the end of

the symphony (Table 1).

Table

1. A

Time

(min.sec)

structural

and

textural

outline

of

the Bird

Symphony.

Texture

00.01

blowing of the wind in the creek

00.29 birdsong ( from 1 to 4 birds)

03 23 water sounds

04.05

5th birdsong added to the texture; pitched water

(chime effects)

16.52

roaring of the creek (no birdsong)

17.44

22.30

31 42

32.02

32.32-32.34

34.35

42.14

42.26-48.28

53 20

59 12-59.20

voice)

birdsong fragment (repeated from the beginning)

second joiker (adding another melodic part); reindeer

bells (chime effects); birdsong

joiks end

reappears

birdsong

53 12

57.00-58.15

reindeer bells; reindeer calls (by human

gradually

Joiker (human voice)

reindeer bells only (birdsong

at 48.28)

49 40-53.12

57.00

birdsong re-enters; roaring creek recedes

bird chorus

sounds

only

birdsong; water

sounds

joikers; birdsong

joiks end

birdsong

silence

This content downloaded from 132.235.61.22 on Fri, 13 Feb 2015 02:06:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

in the background

202

Ethnomusicoiogy,

Spring/Summer

2009

How can we interpret thiswork? The Bird Symphony seems to take us

into a traditional joik performance space; gone are the accompaniments of gui

tars or symphony orchestras. But thework ismore than a representation of joik

authenticity.While there are several examples of composers being inspired by

birdsong, even using recorded bird sounds as part of themusical texture (the

Finnish composer Einojuhani Rautavaara, for example, used a tape ofArctic

bird song inCantus Arcticus, 1912), such bird sounds are given prominence

inValkeapaa's Bird Symphony Valkeapaa spent two years recording birdsong

in his home area?a

landscape of tundra and the creek Adjagorsa (to which

he referred in the poem with which this paper begins). He manipulated his

birdsong recordings in attempting to create a three-dimensional sonic effect

(p.c, Ande Somby, 20 January 2OO8,Troms0, Norway).

The joik in the Bird Symphony is fragmentary, but noteworthy for it

introduces the human presence and is accompanied by reindeer (through

the reindeer bell). It features inValkeapaa's other works, including Beaivi,

Ahcdzan

(The Sun, My Father, a musical composition based on his award

winning poetry). This joikwas performed forme in September 2006 by the

Norwegian joik singerMarit Berit,who sang it as "Ailu's [Valkeapaa's] joik" (a

personal joik), though another joikwas performed at a joik concert as Ailu's

joik. I invested some time in tracing both joiks and might suggest thatMarit

Berit did actually sing the joik thatValkeapaa used as his personal joik and that

recurs inhis recorded repertoire. Indeed, she insisted thatValkeapaa had sung

this to her as his personal joik (interview, Berit, 8 September 2006, Jokkmokk,

Sweden). The other joik, also known as Ailu's joik, seems to be a tribute joik,a

personal joik sung by other singers but not by the subject of the joik himself.

The tribute joik has become so identifiedwith Valkeapaa that it isnow widely

recognized as being his joik. The distinction between the personal joik and

the tribute joik is important not only in tracing the joiks themselves but also

in the implications for considering questions about the authorship of this

work. Valkeapaa sings himself in the Bird Symphony, vocalising his presence

in his home environment. Somby confirmed my identification ofValkeapaa's

personal joik, adding that this joik is a self-portrait inwhich Valkeapaa de

scribes his ambiguous self-perceptions as connected to the land, but also as

an independent individual with a sense of disconnection from society (fos

tered through his boarding school experiences and removal from his family

at a very young age), enabling him to adopt a descriptive perspective on the

world. But the joik also points to theways inwhich nobody can be totally

disconnected since it is related to a very famous traditional joik from the area

where Nils-Aslak Valkeapaa composed his own personal joik. The traditional

joik towhich Valkeapaa's personal joik is related is that of a reindeer herder,

who used to herd reindeer on the other side of the river fromwhere Nils

Aslak's home was situated (interview, Ande Somby, 25 January 2OO8,Troms0,

This content downloaded from 132.235.61.22 on Fri, 13 Feb 2015 02:06:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Ramnarine:

Arctic Fringes and Ethnomusicology

203

Norway). From Somby's account we understand themultiple significances

of the reindeer bell accompanying the human voice in the Bird Symphony

(including biographic, geographic, and historic threads, intermelodic relations,

and

commentary

on

converging

social

and

natural

environments).

The joik techniques in both theJoik Symphony and theBird Symphony

accord with musical analyses ofArctic song genres that have focused on me

lodic and structural aspects, meaning and circularity. In 1942, Tiren described

the composition process as beginning with a shortmelody that is then fur

ther elaborated (cited in Jones-Bamman 1993:116), an analytical insight that

underlies more recent perspectives on the melodic motif as the basic unit

of composition (ibid. :117). Joik is often characterized by repetitive sections,

irregular phrasing determined by breath control rather than structural con

siderations, a distinctive vocal timbre, and rising and microtonal pitches. The

ontological status of joik and its structural and stylistic aspects have posed

considerable analytical challenges to researchers that are reproduced with

regard to the Bird Symphony. Yet, Iwould suggest that this symphony is not

an indigenous appropriation of aWestern art music form. Rather, a "sonic

sensibility" is revealed, leading listeners to an "experiential truth,"to return

to Feld's formulation of acoustemology (1994). But the experiental truths

in the Bird Symphony are not wrapped up only in relation to symphonic

thought. In interviews, Nils-Aslak Valkeapaa commented: "the yoik lasts as

long as you want and its original magic stems precisely from its continuity.

It is like a ring that circles in the air and its structure can be compared with

water moving in harmony with the landscape or thewind that touches the

ground on themountain plateau" (cited inKjellstr6m,Ternhag, and Rydving

1988:1 l).When asked by the Sami scholar Elina Helander:"Does

your artistic

work have a beginning?" he responded: "No, itdoesn't. I have been doing all

this kind ofwork for as long as I can remember. And the opposite also could

be said: I remember doing thiswork before I can remember doing anything

else. I have no beginning, no end, and there also is no beginning, no end in

thework I do. Book after book and work afterwork, the same work goes on

and changes all the time" (cited inHelander and Kailo 1996:87).

Ande Somby states that a joik does not have a beginning and an ending

and that a joik cannot be thought of in terms of linear development, ideas

that resonate with Valkeapaa's discourse. Given that a performer joiks some

one or something it is impossible to think about joik in relation to subject

and object; the joiker and the joiked can be considered an integral part of

the joik (Somby 1995). While analysts have struggled with locating a steady

pulse and have used shifting time signatures in their joik transcriptions,many

Sami musicians think in terms of a pulse that is pervasive, consistent in its

appearance in everyday activity and environment, avoiding linear develop

ment. Notions of pervasive pulse and cyclical musical time are also revealed

This content downloaded from 132.235.61.22 on Fri, 13 Feb 2015 02:06:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

204

Ethnomusicoiogy,

Spring/Summer

2009

in Frode Fjellheim's teaching book, Juoigama

vuodul (2005:15), inwhich

pulse ismapped out in a circle that can be superimposed onto an image of

themilky way and which, in turn, can be mapped onto the Sami drum, the

once sacred instrument of the shaman.

The characteristics of non-separability between subject and object help

us to perceive the integration of the bird, human and reindeer subjects in the

Bird Symphony, and non-separation is also apparent inNils-Aslak Valkeapaa's

poetry, which gives further clues to his compositional conceptualizations:

itwas

not

the wind

you did not hear the bird

itwas

my thoughts

?Trekways

of theWind

1985)

a child

Iwas

when

([1974,1976,1981]

Iwondered why did I not have wings

like other birds

though no longer a child

Iwonder

?The

still

Sun, My Father

(1997:214)

The philosopher Gemot Boehme observes that,"music occurs when the

subject of an acoustic event is the acoustic atmosphere as such, that is,when

listening as such, not listening to something is the issue."Music in this case

"need not be something made by humans." Nevertheless, acoustic ecology

emphasizes human agency despite insights into thewider sonic world. Thus

Boehme suggests thatwhether an environment is experienced as human or

not also depends on qualities in the environment, which are experienced

aesthetically. Music is an "acoustic decoration of public spaces," a formulation

increasingly commonplace with developments in acoustic

The Joik Symphony and the Bird Symphony

technologies (2000:16-17).

can be partly interpreted within the frameworks of acoustic ecology. But,

I think that the indigenous politics expressed through these joikworks in

that has become

the symphonic tradition goes even further. Although the Bird Symphony

is a work thatwe can listen to because of recording technology, this is not

music resulting from twentieth century expansions ofmusical materials (with

can be thought of in

everyday sounds being available for compositions) that

terms of the "conquest of acoustic spaces" as Boehme suggests (2000:15-16).

As Valkeapaa writes in the poem quoted above, the sounds ofwind, the bird,

and human thought are the same, indistinguishable from each other, not

needing to be constructed as distinct. In the Bird Symphony, the idea of the

human as creative agent and author is strained to the extent that it is difficult

This content downloaded from 132.235.61.22 on Fri, 13 Feb 2015 02:06:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Ramnarine:

Arctic Fringes and Ethnomusicoiogy

205

to hear thiswork only in terms of human relationships with the environment.

Of course,Valkeapaa has composed the environment, but the human subject

is located as a part of that environment, rather than in relation to it.Perhaps

this location within and not in relation to nature renders it impossible to

externally impose a pulse on it and allows us tomove nearer to an under

standing ofwhy the joiker, the joik, and the joiked are integrated. This is not

sound as mediation between people and environments, towhich acoustic

ecology alerts us, but a different understanding of the environment inwhich

atwork on the northern fringes of

humans are a part. The acoustemologies

Europe question notions of humans in relationship with their environments

where environments are seen as polities shaped only by human laws and

practices or experienced as human; or are understood in terms of human

dramas played out against scenic surfaces or as subject tomarket evaluations

(see Ohman and Simonsen 2003).While Feld alerts us to how an ecosystem

shapes human musical concepts and creativities in the case of birdsong and

performance amongst theKaluli of Papua New Guinea (Feld 1990),Valkeapaa

takes us some way towards understanding how the joiker, the joiked, and the

joik are one and the same, and how human musical expression is an aspect of

a sonic ecosystem. Valkeapaa takes us away from understanding authorship

and creativity solelywithin environmental determinist frameworks whereby

environments shape human cultures. In fact, in reading Feld's ethnography in

view of critical work on species boundaries, this iswhat the Kaluli are point

ing to as well. Feld writes that bird sounds "metaphorize" human feelings for

the Kaluli, but in song performance, Kaluli "become those very birds" (Feld

1990:85). Valkeapaa writes "you did not hear the bird, itwas I." The social

and political ramifications are profound.

Green

Postcolonialism

and

Sami"

"Ecological

The Bird Symphony challenges the notion that sound mediates between

humans and their environments, invitingus instead to consider human musi

cal

creativity

situated

within

sonic

ecosystems

and

across

species-boundaries.

How we might theorize human musical creativities within such sonic eco

systems, including environments performed by both human and non-human

agents, provides interesting challenges for environmental ethnomusicoiogy.

Iwould

like to draw on further theoretical possibilities from debates on

colonial impacts on environments and species boundaries thatmight move

us towards a deeper appreciation ofValkeapaa's symphonic activism.

The Arctic ecosystem is complex. Bird life is diverse. Current preoccupa

tionswith polar warming have highlighted the fragilityof theArctic environ

ment with flora and fauna habitats at risk. Europe's Arctic fringes have been

subject tomarine and land-based resource development, to pollution through

This content downloaded from 132.235.61.22 on Fri, 13 Feb 2015 02:06:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

206

Ethnomusicology,

Spring/Summer

2009

the dumping of nuclear waste by the former Soviet Union in the Barents

region, to transboundary pollution fromWestern Europe, to forest logging,

and to ozone-layer depletion. Human activity is understood as threatening

to the diversity ofArctic life.Habitats disappear with oil and gas industries,

hydroelectric dams, mining, trawling, forestry,and over-fishing. The issues of

polar warming and climate change have reached the global political agenda.

Accounts of damage to theworld's ecosystems and of themarginalization of

indigenous people under European imperial rule, highlighted inpostcolonial

studies, similarly pertain to ecosystems within Europe itself. Insights from

what is now being called "green postcolonialism," highlighted in a special is

sue of Interventions: InternationalJournal

of Postcolonial Studies (Huggan

and Tiffin 2007), are therefore relevant in thinking about indigenous politics

on Europe's northern fringes.Green postcolonialism draws attention to the

ways inwhich colonialism has fractured and changed the relations between

environment, humans, and animals. Huggan and Tiffinnote that a postcolonial

environmental ethic as away of reconfiguring "the nature of the human and

the place of the human in nature" means investigating "the category of the

'human' itself" (2007:7).

In traditional Arctic belief systems, a shaman can turn into a flying rein

deer, a belief that reveals the category of human as ambiguous. Even up to the

in folklore archives about Sami shamans

1930s, legends were documented

who were able to turn intowild animals like bears and wolves. Contemporary

joik singers continue to perform reindeer, bird, orwolf sounds. In 2007,1 heard

Katarina Rimpi joiking Arctic birds and Simon Marainen joiking reindeer in

Jokkmokk'sWinter Market, one of themajor winter trading and festival ven

ues in the Swedish Arctic thatwas founded by King Karl EX over 400 years

ago. Ande Somby joiked a ptarmigan and a wolf at the opening ceremony

of theArctic Frontiers conference (held inTromso, Norway, January 2008).

Wimme's performance of an animal joik in the Ijahis Idja (Nightless nights)

Festival on the shores of Lake Inari, Finland, inMay 2007 likewise invited

an investigation into the category of human. His joik started as a bird, then

changed to a wolf, and ended with a church hymn, offering complex, mul

tilayered musical commentaries on the borders of human and non-human

creativity, on ecology, and on spirituality.

These are of course interpretive moves on my part and they are offered

by way of suggesting that there is something more in these performances

than confirmation of amodel presenting humans in relationship with nature

towhich indigenous populations have been subject. Discussions of indigene

tropes regarding

ityand environment can be read inview ofwell-established

human relationships to nature, but these tropes are as restrictive as they

are liberating in indigenous politics. As Mathisen points out, descriptions of

indigenous people as "nature-bound, living in a special harmony with nature,

This content downloaded from 132.235.61.22 on Fri, 13 Feb 2015 02:06:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Ramnarine:

Arctic Fringes and Ethnomusicoiogy

207

understanding the deep ecology of nature, having a special knowledge of

powers in nature, and so on, proliferate even today" (Mathisen 2004:18-19),

and are found in ethno-politics, struggles for land rights, eco-politics and

environmental philosophy. Rather than confirming such descriptions, we can

interpretworks like the Bird Symphony as posing fundamental questions

about the human/nature relationship. The presentation of joik in the Bird

Symphony stands apart from representations of Sami as people in commu

nion with nature as it leads us to question the very notion of the human in

relation

to nature.

For me,

this question

arises

from

contemporary

environ

mental ethical discourses, but the Sami and nature have been represented

in various ways as Mathisen (2004) outlines. In seventeenth-century reports,

Sami were

the

seen

as wild

late nineteenth-century,

and

as having

an un-natural

control

a perceived

closeness

to nature

over

nature.

was

an

In

indica

tion of being on a lower step in cultural evolution, but itwas also regarded

as a threat to civilization, health, and modernization,

excepting reindeer

herders who were depicted more favorably in themode of "noble savages"

(ibid.:23). Reindeer herding was also significant in the early stages of the

Sami indigenous movement, and it continues to have symbolic importance.

It is considered to be the "most typical Sami way of life,"and it generates

"the idea of 'ecological Sami'who are close to nature and live in ecological

harmony" (ibid.: 19).5 Mathisen suggests thatwhile the image of ecological

Sami may seem a good opportunity to give voice to the indigenous people

of theArctic North it turns out in reality "to be based on themajority's myths

about nature people and noble savages" and as such it is "too fragile tomeet

the demands of future ethno-political work" (ibid.:29).

What are the insights to be gained from focusing on musical perfor

mance? The political work of indigeneity inworks like the Bird Symphony

is not based on notions of Sami being close to nature per se. In contempo

rary recordings and live performances by joikers such asWimme Saari,we

can hear the differentways inwhich modern environments impact on joik

performance with the incorporation of the sounds ofmotorcycles and snow

mobiles aswell as birds and wolves. The descriptions of being close to nature

are fraughtwith assumptions about the relationship between humans and

nature as well as about timeless lifestyles that are inconsistent with modern

Sami uses of snowmobiles and automobiles, for example, as essential contem

porary tools formobility even as reindeer caravans and goahta (traditional

mobile homes) are maintained. Through the performance of modern sonic

environments, together with use of contemporary recording technologies

and engagement with popular aesthetics, we can understand the joiker, Ingor

Antte Ailu Gaup's comment that "a basic joikmelody ismerely amodel that is

subject to constant reinterpretation inperformance" (cited inJones-Bamman

2003:47). Perhaps we can also understand performing environment as more

This content downloaded from 132.235.61.22 on Fri, 13 Feb 2015 02:06:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

208

Ethnomusicology,

Spring/Summer

2009

than an expression of closeness to nature conceived in narrow terms that

lock Sami in a mythical past of harmonious relationship with an external en

vironment. The political work of indigeneity carried out through performing

environment is to critique market economies and world views that promote

narrow approaches to nature as either resource/commodity subject to human

under the steward

ownership and exploitation or as preserved/conserved

ship of humans. In this regard, postcolonial

theory is particularly relevant

for indigenous politics as both discourses offerways of examining relation

ships of power, of recovering values and self-esteem, and of dismantling and

rejecting beliefs that have been imposed through processes of colonization.

If external representations of Sami as "ecological" people are too fragile for

any real political work, the self-representations of Sami have been crucial

to the processes of asserting land rights, histories, and the validity of indig

enous philosophies, aswell as to rejecting external (colonial) representations.

The (post)colonial political sentiments inValkeapaa's Trekways of theWind

in lines such as:

1985) cannot be misunderstood

([1974,1976,1981]

Did

tell you

anyone

live in Samiland

that we

Did they say

this is Sapmi

Did theyalso admit

that this is ours

Or did they talkabout

the primitive

culture

with simple people

And later in the same volume:

until now have they realized

who

lived here

that the people

ten thousand

years ago

to become

melted

the Sami

Not

That is a long time

The wanderings of the Egyptian pharoahs

riches of the Roman

empire

culture

glory of the Greek

ifyou compare

short moments

The

The

How

I respect

the lifeof the ancient Sami

and how meaningless

for decades

for centuries

to have

learned

the national

days

of other

nations.

Valkeapaa's symphonic compositional processes alert us to an aspect of

such (post)colonial indigenous politics in their expression of an environmen

This content downloaded from 132.235.61.22 on Fri, 13 Feb 2015 02:06:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Ramnarine:

Arctic Fringes and Ethnomusicology

209

tai ethic that stands in contrast to notions of the human actor as removed

and as mastering nature. The indigenous politics in

symphonic activism moves us beyond the emphasis on sound

Valkeapaa's

from the natural world

mediating between humans and environments habitual in the discourse of

acoustic ecology, aswell as beyond the circumscriptions of "ecological Sami."

In traditional Sami concepts of the sacred landscape, nature is recognized and

through human activities that are narrated linking people

comprehended

to generations past and future. Traveling a pathway is to act in history and

in the future,and contemporary practices take place in a continuum where

there is no beginning and no end (Nergard 2004:91).

Such concepts can be understood within the frames of deep ecology,

but they are also reminiscent of Sami analytical commentaries on joik. For

JohanTuri, an indigenous commentator, joiking "is the art of recalling other

people. Some are remembered in love, some in grief. There are poems about

parts of the country and about animals?the wolf, the reindeer, the wild

reindeer" (Turi 1931:20). Another Sami commentator, Israel Ruong outlines

three distinct motifs that recur in joiks depicting: (1) the landscape, (2) the

reindeer, and (3) human beings. He notes "complex joiks" too, inwhich "ele

ments from all three motif groups are interwoven to form a whole" (Ruong

1969:15). A joik to a mountain, for example, "alludes not only to themoun

tain itselfbut also to the reindeer that graze or have grazed upon it and the

people who have or have had it for their pasture" (ibid.:25). Somby ques

tions the ethical basis of nature/human relations, critiquing perceptions of

as removed

nature

an economic

arguing

that

from

humans?as

a resource

or commodity

that

fits into

paradigm of human ownership. He turns to joik not by way of

sound

mediates

between

humans

and

their

environments,

but

to suggest an alternative environmental philosophy:

are Yoiks

for persons,

In our tradition itwas very

animals, and landscapes.

for the personal

if

like getting a name

identity to get a yoik. Itwas

own

a

had

similar

ritual connota

you got your

yoik.Yoiking

landscape

possibly

tion, and the same goes for an animal's

yoik. It is not easy even for the trained

There

important

ear

to hear

an animal's

yoik, a landscape's

yoik or a

so

that

don't

differ

much

between

you

person's

perhaps

emphasises

as you regu

the animal-creature

the human-creature,

and the landscape-creature

context. Your behaviour

will

therefore maybe

larly do in a western

European

the differences

between

yoik. That

be more

inclusive

towards

animals

and landscapes.

can have ethical

that we

not

emphasises

spheres

but also to our fellow earth and our fellow animals.

fellows? (Somby 2000:4)

In some respects

this also

fellow humans

just towards

Can you own some of your

Somby critiqued the species boundary furtherwhen

he told me:

Ifyou thinkof yourself also as awolf would you then like to killwolves? Or if

this wolf

is a transformed

you think that perhaps

would

you then like to grab your gun and shoot

that is out on a mission,

person

it?... Perhaps

these other ways

This content downloaded from 132.235.61.22 on Fri, 13 Feb 2015 02:06:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

210

Ethnomusicoiogy,

Spring/Summer

2009

of thinking that I carry different animals

inme show that if I harm animals

I am

are predators, we

also harming myself...

Even ifwe

are carrying parts of other

in us. (Interview,

25 January 2OO8,Troms0,

species

Norway)

Somby's perspective corresponds to a postcolonial environmental ethic re

configuring human/nature relations. Valkeapaa, too,made such perspectives

(The Sun, My Father) (1997:119),

explicit inworks like Beaivi Ahcazan

to

further

clues

his

providing

compositional aims in the Bird Symphony:

what

gave me

this mind

birdmind

to flywith

and still

I depart

so terrible to leave

when

not

even

everything

in the air

a path

to reveal

where I have flown

if I have

ever been

Concluding Thoughts

The second part of the poem quoted above leads me to some concluding

thoughts regarding environmental history, geological time, and Valkeapaa's

legacy. Pointing to the brevity of human existence, the joik is but a few mo

ments in themusical texture of the Bird Symphony In relation to geological

time, then, the human presence isfleeting. The reappearance of the joik singers

towards the end of thework once again gives way to birdsong, promoting a

specific perspective on the place of humans in the grand narrative of the earth.

Such a reading of theBird Symphony resonates with tliinking about geologi

cal time in postcolonial

theory and highlights another point of coincidence

the politics of indigeneity and of the postcolonial. Seen from the

perspective of geological time, the differencing processes (both imposed and

two of the political mecha

asserted) of indigeneity and postcoloniality?as

nisms through which people are understood and understand themselves as

being different?are only a detail of the human experience in the longer time

frames of environmental history. Thus the struggles over minority status?the

between

in theJoik Symphony recede in

political assertions of indigeneity?expressed

the longer history of Sami (Valkeapaa's respect for the ancient Sami persisting

over the lifetimes of various imperial configurations), which in turn are part

of the longer ebb of geological time expressed in the Bird Symphony From

this perspective, the politics of indigeneity are not about asserting a unique

This content downloaded from 132.235.61.22 on Fri, 13 Feb 2015 02:06:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Ramnarine:

Arctic Fringes and Ethnomusicoiogy

211

spirituality or relationship to the environment. Rather, we can ask further

questions about humans, environments, and creativity.We can confront the

limitations of thinking through the social, the natural, and the cultural. In

this respect, it is significant thatValkeapaa chose the symphony as a medium