Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Why Cheap Green Coffee Does Not Make Cheap Cappuccino?: A Bag of Green Coffee Is Equivalent To 60 Kilograms Net

Caricato da

Lk KtTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Why Cheap Green Coffee Does Not Make Cheap Cappuccino?: A Bag of Green Coffee Is Equivalent To 60 Kilograms Net

Caricato da

Lk KtCopyright:

Formati disponibili

FULBRIGHT ECONOMICS TEACHING PROGRAM

CE02-02-4.0

Jan 21, 2002

NGUY EN XUA N THANH

WHY CHEAP GREEN COFFEE DOES NOT MAKE CHEAP

CAPPUCCINO?

After oil, coffee is arguably the second most important commodity as it constitutes an important source

of foreign income for several some developing countries. Coffee, like any other agricultural products, is

a cyclical crop. When the supply of coffee is large, the world price of coffee falls. Many farmers then go

out of business, or they switch from coffee to other similar crops. Consequently, the world supply of

coffee falls, and so prices rise again. Once again, it becomes financially worthwhile for farmers to

produce coffee instead of those other crops.

To counter this cyclical pattern, several major coffee-growing countries set up the Association of Coffee

Producing Countries (ACPC) in 1993. The members of the ACPC were Angola, Brazil, Colombia, Costa

Rica, Ivory Coast, DR Congo, El Salvador, India, Indonesia, Kenya, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda, and

Venezuela. The purpose of this organization was to control coffee prices by adjusting coffee supplies

from the member countries.

However, just as the coffee producing countries were debating the idea of a coffee cartel like OPEC,

other countries, which never produced coffee before, started developing huge new coffee plantations.

Among these new comers was Vietnam, which produced as little as 1.2 million bags of green coffee in

the 1990-91 season. The 1990s saw a sharp increase in Vietnams coffee production, resulting from the

massive expansion of growing areas in its Central Highlands; and from productivity improvements.

The total area of Vietnams coffee plantations increased from 200,000 hectares in the mid-1990s to

500,000 hectares in 2000 / 01. During the same period, the average productivity increased from 1 ton per

hectare to 1.8 tons per hectare. In 2000 / 01, Vietnams production of coffee reached 15 million bags.1

This made Vietnam the second-largest coffee producer in the world after Brazil, accounting for a tenth

of the total global coffee production.

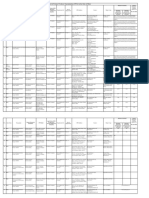

Figure 1: Vietnams Coffee Production

Millions of Bags (60 kg)

16

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

00-01

99-00

98-99

97-98

96-97

95-96

94-95

93-94

92-93

91-92

90-91

89-90

88-89

87-88

86-87

Source: ACPC, Review of the market situation, October 2001.

A bag of green coffee is equivalent to 60 kilograms net.

This case study was prepared by Nguyen Xuan Thanh, lecturer at Fulbright Economics Teaching Program. Fulbright Economics

Teaching Programs cases are intended to serve as the basis for class discussion, and not to make policy recommendations.

Copyright 2002 Fulbright Economics Teaching Program

Why cheap green coffee doesnt make cheap cappuccino?

CE02-02-4.0

It was also revealed that although various ACPCs production restriction programs were in place, they

were not complied with by the members. Even Brazil, the largest coffee producer and the most rigorous

enforcer of ACPCs retention plan (the withholding 20-percent of coffee production), eventually gave

up its commitment and started selling its reserves of coffee by August 2001.

As a result, many countries had been expanding their coffee production while the global demand for

coffee was flat. An estimate by ACPC, shows that the supply of coffee increased 3.6 percent a year on

average, while the demand for coffee only increased by 1.5% a year throughout the 1990s. Total

production of green coffee in 2000 / 01 was about 115 million bags. This exceeded total consumption

(105 million bags), by about 10 percent..

Figure 2: Worlds Total Coffee Production

Source: International Coffee Organization, 2002.

Consequently, the price of coffee beans in 2001 plunged to their lowest level for 30 years. Coffee

farmers claimed that the coffee price had fallen below actual costs of production. Figure 3 below shows

that the average price of green coffee by September 2001 was only 32% of that in January 1998.

Figure 3: Fluctuations of Coffee Prices

Coffee Indicator Prices

(Monthly Averages 1991-2001)

Coffee Indicator Prices

(Monthly Averages 1998-2001)

220

140

200

120

180

100

US cents per lb

US cents per lb

160

140

120

100

80

80

60

40

60

40

20

20

0

Source: The International Coffee Organization (ICO).

Page 2 of 3

Sep-01

Jan-01

May-01

Sep-00

Jan-00

May-00

Sep-99

Jan-99

May-99

Sep-98

Jan-98

May-98

Jan-01

Jan-00

Jan-99

Jan-98

Jan-97

Jan-96

Jan-95

Jan-94

Jan-93

Jan-92

Jan-91

Why cheap green coffee doesnt make cheap cappuccino?

CE02-02-4.0

According to Oxfam, a non-profit organization, an immediate impact from the drop in coffee prices was

felt by coffee farmers, who at the end of the 1990s numbered around 7 to 10 million people. The impact

was especially harsh on small-scale farmers, who were unable to benefit financially from savings,

during the good years of rising prices, to see them through the difficult times of falling prices. Oxfam

predicted that the coffee farmers economic difficulties would soon transform into education, health,

and social problems.

Intriguingly, the price of processed coffee in supermarkets did not fall. And that was the reason why

several non-profit organizations accused giant coffee sellers like Nestl and Procter & Gamble, and

fashionable coffee shops like Starbucks of reaping profits on the back of impoverished coffee farmers.

No tabloid campaign was launched into why the likes of Starbucks can get away with asking 3.35 for

a raspberry mocha chip cream frappuccino, when the price of coffee beans has never been cheaper,

wrote the Observer newspaper in London.

Oxfam says the cost of coffee beans accounts for less than 7% of the eventual cost of a cup of coffee paid

by Western consumers - the rest, over 90%, goes to coffee processors and retailers.

While sharing in the concern of falling prices of coffee beans, coffee roasters and retailers rejected

Oxfams claim of unfair trading practices. The British Coffee Association (BCA) says Oxfam "fails to

address the fundamental economics of the coffee market in the long term."

"Simply increasing the prices for green coffee beans without implementing the appropriate controls on

production would not help the livelihood of the growers in producing countries in the longer term,"

argues the BCA.

The coffee retailers argument starts right at heart of Oxfams claim. It is true that the cost of exported

coffee beans accounts for only 7% of the final price of roasted coffee. The remaining costs come from

processing, transport, storage, and taxes. Taxes, such as export duty and sales tax, are fixed expenses.

Wages, insurance and freight, and storage costs have all increased over time. Thus, although the price

of green coffee has been falling sharply, the price of roasted coffee has not.

The percentage share of the cost of actual coffee beans in the end price of a cup of cappuccino, is even

less than 7 percent if one takes into account rising shop rents and staff costs. Coffee shops in countries

like the UK typically make 42 cents for every $2.5 cup of coffee. Starbucks, therefore, said that the

falling price of coffee had no effect on pricing policy.

Various proposals had been suggested to overcome the problems of falling coffee prices. Oxfam called

for an internationally-agreed minimum coffee price of $2.2 per kilogram - about doubled the 2001 level.

Others favored output restriction solutions. One method was to destroy low quality beans before they

reached the market. As estimated by the Natural Resources Institute, each million bags of low-quality

coffee removed from the global market would raise global prices by two US cents per pound for coffee.

Page 3 of 3

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Individual Budget PlanDocumento1 paginaIndividual Budget PlanLk KtNessuna valutazione finora

- Graduate Request For Transfer Credit - TTUDocumento1 paginaGraduate Request For Transfer Credit - TTULk KtNessuna valutazione finora

- Detail Outcall - Dec 10 2014 - Jan 10 2015Documento4 pagineDetail Outcall - Dec 10 2014 - Jan 10 2015Lk KtNessuna valutazione finora

- The Asian Financial CrisisDocumento13 pagineThe Asian Financial CrisisLk KtNessuna valutazione finora

- 1.3.5 General Vector and Tensor Algebra Identities: A A A ADocumento1 pagina1.3.5 General Vector and Tensor Algebra Identities: A A A ALk KtNessuna valutazione finora

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5795)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (345)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1091)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- GR No 77830Documento4 pagineGR No 77830Geds DNessuna valutazione finora

- Break Even Agri MitraDocumento9 pagineBreak Even Agri Mitraprasadkh90Nessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 2 FoubergDocumento4 pagineChapter 2 Foubergi1958239Nessuna valutazione finora

- NZ H 18811230Documento8 pagineNZ H 18811230pearlynpuayNessuna valutazione finora

- Redefining Agricultural Yields: From Tonnes To People Nourished Per HectareDocumento10 pagineRedefining Agricultural Yields: From Tonnes To People Nourished Per HectareAtha FrrNessuna valutazione finora

- DLP Oancii G11 01 - 19 - 23Documento3 pagineDLP Oancii G11 01 - 19 - 23KrizzleNessuna valutazione finora

- Napier Tumbukiza MethodDocumento3 pagineNapier Tumbukiza MethodBright KadengeNessuna valutazione finora

- 13 Impact of Tillage Plant Populationa and Mulches On WeedDocumento4 pagine13 Impact of Tillage Plant Populationa and Mulches On WeedHaidar AliNessuna valutazione finora

- List of FPOs in The State of BiharDocumento2 pagineList of FPOs in The State of Biharanon_493704527100% (2)

- Integrated Watershed ApproachDocumento3 pagineIntegrated Watershed ApproachSuhas KandeNessuna valutazione finora

- Ujian Penilaian Bahasa Inggeris Tahun 3 KSSR Kertas 2Documento5 pagineUjian Penilaian Bahasa Inggeris Tahun 3 KSSR Kertas 2Sistem Guru Online67% (3)

- Geomorphology and GIS Analysis For Mapping Gully Erosion Susceptibility in The Turbolo Stream Catchment (Northern Calabria, Italy)Documento18 pagineGeomorphology and GIS Analysis For Mapping Gully Erosion Susceptibility in The Turbolo Stream Catchment (Northern Calabria, Italy)Anonymous Sa0YoeKpNessuna valutazione finora

- Agriculture and Fisher Arts QuestionnairesDocumento92 pagineAgriculture and Fisher Arts QuestionnairesLaila UbandoNessuna valutazione finora

- Varietati de GinkgoDocumento5 pagineVarietati de GinkgoLavinia BarbuNessuna valutazione finora

- Small Key (Paz Latorena)Documento3 pagineSmall Key (Paz Latorena)Jae ClefNessuna valutazione finora

- Buringh Soil and Soil Conditions in IraqDocumento338 pagineBuringh Soil and Soil Conditions in IraqAhqeterNessuna valutazione finora

- KootanchoruDocumento4 pagineKootanchoruAravindan MuthuNessuna valutazione finora

- Cost Breakup of Vertical Farms - ComponentsDocumento3 pagineCost Breakup of Vertical Farms - ComponentsDev MaletiaNessuna valutazione finora

- GoddaDocumento21 pagineGoddanunukanta100% (1)

- English Notes of MatricDocumento70 pagineEnglish Notes of MatricAli khan7Nessuna valutazione finora

- Vegetables BreedingDocumento83 pagineVegetables BreedingSantosh MishraNessuna valutazione finora

- Variety Vs CultivarDocumento2 pagineVariety Vs CultivarPriya SharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Dairy Project Model Financial Calculator From DairyFarmGuide PDFDocumento4 pagineDairy Project Model Financial Calculator From DairyFarmGuide PDFgauravbimtechNessuna valutazione finora

- Cereals and Cereals by ProductsDocumento28 pagineCereals and Cereals by ProductsDr-Shoaib MeoNessuna valutazione finora

- General Agriculture 1Documento76 pagineGeneral Agriculture 1Suraj vishwakarmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Power Problems, Problems of Disparity in Economic, Social and Political Power"Documento5 paginePower Problems, Problems of Disparity in Economic, Social and Political Power"YousufnaseemNessuna valutazione finora

- AI8201 r17 Principles and Practices of Crop ProductionDocumento1 paginaAI8201 r17 Principles and Practices of Crop Productionvimbee alipoon100% (1)

- Afa 10 Agri Crop q2w1Documento9 pagineAfa 10 Agri Crop q2w1AlbertoNessuna valutazione finora

- AGRICULTUREDocumento460 pagineAGRICULTUREmehNessuna valutazione finora

- Breeding MealwormsDocumento2 pagineBreeding MealwormsblackriptoniteNessuna valutazione finora