Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Mingles in Foreign Language Classroom - 2014

Caricato da

aamir.saeedCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Mingles in Foreign Language Classroom - 2014

Caricato da

aamir.saeedCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Elena Borzova

Russia

Mingles in the

Foreign Language Classroom

polls or interviews and address multiple respondents in order to reach a

specified goal.

The distinctive features of a mingle activity are that all the students

work simultaneously, in pairs or small

groups, and switch from one classmate to another while speaking, listening, and taking notes. Face-to-face

interaction with at least a few other

students is the principal goal. As soon

as two individuals have finished an

interaction, they change pairs either

at random or in an organized fashion; for example, if they are standing

or sitting facing each other in two

circles, pairs change when one circle

moves clockwise. As for the teacher,

he or she cannot control every student involved in a mingle activity and

usually focuses on those who may

need special support.

The organization of mingles relies

on the gapdifference principle and

may take the form of the information

gap, the experience gap, the opinion

gap, or the knowledge gap (Rees

2003), motivating students to change

partners in order to discover the

witching conversational partners in the English as a foreign

language (EFL) classroom has

long been an effective way to involve

students actively in communicative

interactions and increase their talking

time. But based on my observations

and experience, few foreign language

teachers actually use this classroom

management strategy on a regular

basis. There are reasons why teachers

are reluctant to incorporate mingles

activities that involve switching from

one interlocutor to anotherinto

their lessons, including fear of distractions, lack of time, and uncertainty

about when and how to apply them.

The aim of this article is to describe

a few examples of mingles and share

advice on how to use them effectively

in the EFL classroom.

What is a mingle?

A mingle is an activity where a

student approaches a classmate, talks

for a while, and then moves on to

speak to another classmate. This type

of interaction is typically informal,

though it can be formal as well, such

as when students conduct opinion

20

2014

u m b e r

n g l i s h

e a c h i n g

o r u m

tion for further, more challenging tasks, such

as project or research work and essay writing.

Therefore, the students responsibility for the

process and its outcome grows considerably.

Indeed, these characteristics of mingles produce notable benefits for students in terms

of requiring interaction, collaboration, and

critical thinking.

information or facts necessary to close the

gap. In arranging mingles, the teacher takes

advantage of actual differences among students or intentionally creates differences by

providing sufficient materials to highlight the

diversity among students. For example, every

student goes around the room writing down

the birthdays of ten other students, or the

teacher hands out partial information about

an English-speaking country to each student,

who then fills out a table by collecting missing

data from every classmate in the room.

Mingles are similar to real-life situations in

which we seek the same information from different people in order to find something out

or to share the same story. According to Robertson and Acklam (2000, 18), mingles allow

constant repetition of a particular question or

collection of the opinions of many students.

This gives students the opportunity to repeat

the same utterance several times, which gradually raises confidence in their use of English.

Therefore, mingles promote both accuracy

and fluency, provided that they are properly

organized into the lesson plan.

Mingles also enliven lessons because students move around and talk to their classmates without the teachers direct supervision.

Every new partner brings some novelty to

the communicative situation and, willingly

or unwillingly, students learn to take into

consideration the characteristics of their interlocutors. To reach understanding, they need

to speak clearly and sometimes explain certain points or words as they adjust to a new

partner. As a result, students feel both more

relaxed and more involved.

A mingle activity should not appear out

of the blue in an isolated fashion, however.

Students should be prepared for the activity in terms of both language and content.

Therefore, a few exercises that allow them to

brush up on needed language forms and to

organize their ideas should precede mingles.

Mingles are part of a chain of tasks intended

to achieve a certain, well-specified goal. While

doing mingle work, students collect and process varied information and opinions. The

outcome achieved in the mingle is a prerequisite for the subsequent work performed

by every student either in class or at home.

Students get a broad perspective of the issue

under discussion, which forms the founda-

n g l i s h

e a c h i n g

o r u m

Mingle procedures

The mingle activity can be implemented

by (1)walking around and talking freely with

other students or (2) rotating pairs, where

students form inside and outside circles and

face each other; each student from the outside

circle, after speaking with the person facing

him or her, moves one step (or one seat)

clockwise to speak with a new classmate from

the inside circle. The rotating-pair mingle

typically requires more organization.

A wide variety of materials are appropriate

to use with mingles, including texts, pictures,

videos, objects, or problems for discussion. In

addition to incorporating speaking and listening, mingles can feature writing, drawing, and

dramatic action. Moreover, keeping in mind

the students proficiency levels and readiness to work independently, the teacher can

involve all the students in the mingle activities

or only half of them (in which case the other

half will be engaged in a different activity).

With mingles, the teacher is guided by

the need to (1) avoid monotony of the lesson flow; (2)provide ample practice for every

student; and (3)prepare students properly for

a more challenging activity. All mingle activities are governed by considerations of allotted

time, the number of students each person is

to address, and the assignment, which can

be either standardized or different for every

student in the classroom.

In general, the key idea of this classroom management strategy is diversity of

studentsdiversity of materials and tasks

(Borzova 2008), which promotes meaningful

student interaction and creates an amplified

learning environment offering varied opportunities for effective learning and communicating. Practical suggestions for teachers that

describe mingle activities include a tea party

strategy (Jonson 2006, 194196); questionnaires (Edge 1993, 71); opinion polls (Klippel 1984, 5); surveys (Seymour and Popova

Number

2014

21

2003, 1314); find your match (Vogt and

Echevarra 2008, 112); and find out who

(Klippel 1984, 54).

explain the rule or dictate the sentence to the

whole class.

Form-focused mingle 2

Each student is given a different sentence.

The teacher makes sure that there is the same

number of sentences as there are students.

Students mingle and dictate their sentence

to everyone. When each student has written

down every sentence, students form pairs

and arrange the sentences into a coherent

story that they read aloud later as a class. This

activity can be conducted as a whole class or

in large groups.

Possible follow-up activities: The students

compare the facts in the text with actual conditions, or they change the story so that it is

true to their lives.

Form-focused tasks are often ignored by

communicative methodology. But my experience shows that students need this type of

task to retain language forms in their longterm memory and master sentence-building

mechanics. Another advantage is that students simultaneously learn the material while

teaching others. Moreover, mingle classroom

management allows students to complete

many more assignments within the same time

period and thus improves the automaticity of their subskills. It makes learners more

confident while talking and writing and thus

facilitates both the accuracy and fluency of

their speech. Such tasks therefore play a supportive role in the development of English

communicative competence.

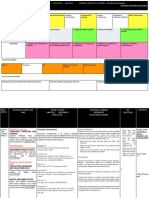

Three types of mingle tasks

Depending on the lesson, mingle tasks in

the EFL classroom can focus on (1)language

(form-focused mingles); (2) communicative

functions (form-focused mingles in communicative disguise); and (3)meaning (meaningfocused mingles). Examples of these tasks are

illustrated in the following sections.

Form-focused mingles

Form-focused mingles are aimed at subskill reinforcement through active recycling of

vocabulary and grammar. Following are two

examples of such tasks.

Form-focused mingle 1

The materials used in this mingle activity depend on the grammar or vocabulary

the teacher wants the students to recycle. To

begin, each student receives and completes a

writing task, such as the following types:

Use the correct form of the verb in

brackets: Jack London [be] born in

San Francisco.

Insert the correct form of the missing

words: It ______ a lot ______ time

and effort to ______ grammar.

Change the sentence by inserting the

word in brackets: Have you been here

before? [when]

Change the underlined subject of each

sentence into the plural form: Every

child needs love and care.

Arrange the given words into a meaningful sentence: like, place, there, home,

no, is.

Add at least two words that you know

for each blank to create a meaningful

combination: ______ a conclusion;

a/an [adjective] decision; to come up

with a/an [noun].

Form-focused mingles in communicative

disguise

Form-focused mingles in communicative

disguise help learners practice grammar and

vocabulary in simple situations with a focus

on communicative functions, such as asking

for advice, making suppositions, or expressing

regret. Sometimes students are expected to

act out short dialogues in standard situations,

such as asking directions, inviting everybody

to do something together, or planning a

weekend.

In order to achieve a communicative goal

with this task, students repeatedly address

different classmates while using prescribed

language items. As a result, the monotony

of repetition is enlivened by the diversity of

partners, who each time contribute something

The teacher quickly checks the students

work. The student then becomes the expert

regarding the item and mingles, switching

from student to student, asking for answers,

and checking the accuracy of the responses.

Possible follow-up activities: The teacher

asks every expert to choose the most difficult examples on his or her card and either

22

2014

Number

n g l i s h

e a c h i n g

o r u m

Possible follow-up activity: Ask the students

to decide which classmate or classmates they

have much in common with.

new to the content depending on their personal experience, opinion, or attitude towards

the subject matter. This reflects the wide

diversity of content that is possible to express

within the unity of the language that is to be

practiced (Larsen-Freeman 2012). Two classic

examples are the mingle tasks Find Someone

Who ______ and Poll Your Classmates.

Poll your classmates Task 2

In this task students set out to find out

how well they know each other. Each student

receives a different classmates name and polls

all the other students about this individual,

taking brief notes to remember who says what

about that person. Then each student checks

the answers with the person he or she has been

asking about to see if the findings are true.

The questions can be written on the board.

For example:

Find someone who ______ task

This task allows students to practice different tenses. To practice the present simple tense,

half the students complete a survey on how

their classmates spend their weekends, evenings, summer holidays, winter holidays, etc.

For practice with the present perfect tense,

the situations will change, and half the students will complete a classroom survey by

finding out answers to questions such as these:

Does ______ enjoy going to school?

Why do you think so?

What is ______s favorite subject?

Why do you think so?

What school subject does ______ dislike? Why do you think so?

What interesting places have you visited?

What useful books have you read?

What exciting movies have you seen

recently?

What well-known people have you

met?

What exotic dishes have you tried?

Possible follow-up activity: As a class, the

students discuss who knows each other very

well, supporting their conclusions with the

facts from the answers they received. Then

they write their own answers to the same

questions.

Variation: Every student gets a jumbled

question. The first task is to restore the correct

version and check the result with the teacher.

Then each student asks every classmate to do

the same task and answer the question.

Possible follow-up activities: Working as a

class, students report their findings by summarizing the answers. Then they can do a

quick write-up, either answering the questions

they asked or mingling to describe their classmates experiences.

Poll your classmates Task 3

Each student is provided with a text containing a description of an imaginary family,

town, school, street, or house. The text has

several versions that do not exactly match.

Students mingle with others and ask questions

to identify these differences. The questions

can be written on the board or displayed on

an overhead projector, or students can make

up their own. Here is an example of a text

describing a town. In parentheses you can see

differences that could appear in another version of the text (each version of the text would

have something different in these sentences):

Poll your classmates Task 1

Students write down three singers, school

subjects, sports, or other things or activities

they dislike. Students mingle and address others by turn to find somebody who has similar

dislikes. For example: I cant stand ______.

Do you agree with me? (I suggest dislike

here rather than like because students are

usually asked to express their preferences. As a

result, many have trouble explaining why they

do not like something. Asking students to talk

about their dislikes from time to time provides practice with this function and related

vocabulary.)

n g l i s h

e a c h i n g

o r u m

This nice town is located in the north

(west) of the United States on the

bank of a beautiful river (on the shore

of a beautiful lake). It is possible to

get here either by ferry or by car (only

by car). It takes about fifty minutes

(half an hour) to drive to this place

from the nearest city. More than eight

thousand (nine thousand) people live

here. The majority of the residents

are retired (students of the college

Number

2014

23

located here). This place is visited

by crowds of holidaymakers because

it is a well-known ski resort (nature

reserve). Another tourist attraction

is the local spa center (Museum of

Indian Crafts). Its a great place to

visit to become familiar with a typically American lifestyle (to relax).

Students note how many people are

interested in attending as well as the

reasons their classmates give for wanting to attend or not.

2. The whole class ranks the events according to their popularity and explains the

reasons they are popular or unpopular.

Examples for Option 2:

1. Students think of their favorite place

in the city and how to best explain the

directions to that place from the school.

2. Students mingle with others and ask,

How can I get to your favorite place in

our city from here? Students listen to the

directions and guess what the place is.

3. As a class, students discuss their favorite

places in the city.

Possible follow-up activity: First the students

point out the differences they spot, and then

use the text as a model to speak and write

about a real town.

Poll your classmates Task 4

Each student receives a different text,

which should be shortless than ten sentencesand meaningful. Brief descriptions

of famous cities, places, popular hobbies, or

controversial opinions about school or fashion

work well in this activity. The students read

their texts and prepare a few questions based

on them. While mingling, they ask everybody

to read the text. Then they retrieve the text

and ask their partner to answer the questions

they prepared or to reproduce the text. This

usually takes about two to three minutes.

It is important to provide texts that arouse

varied emotions or thoughts. This activity can

also be done with photographs or pictures;

for example, students show photos of young

people wearing extravagant clothes and then

ask questions about teen fashion.

Possible follow-up activities: The students

discuss which ideas from the texts they agree

or disagree with, which place they would like

to visit and why, or what impressed them in

the pictures they saw.

Possible follow-up activity: The teacher asks

pairs of students to act out a similar conversation in front of the class, changing some

details of the previous situation.

Form-focused mingles in communicative

disguise should be used often because this

type of activity is an essential step forward to

authentic communication. Though students

are bound to use certain language structures

or text models, in their reactions they are

expected to connect those structures or models to real-life experiences and express their

own attitudes. These tasks are especially helpful to students with low proficiency levels and

in mixed-ability classes.

Meaning-focused mingles

In a meaning-focused mingle, students share

and collect both information and opinions,

which they will later use for doing projects

or research. This information is derived from

varied texts distributed by the teacher or based

on the students personal experiences. Therefore, meaning-focused mingles can be based on

(1) sharing the content of texts (short stories

and cases, ads, statistics, research findings, opinions) or (2)collecting information and opinions

with polls and questionnaires. The texts and

questions can be offered by the teacher or created by students themselves. The interaction

is focused on the exchange of facts, opinions,

problems, or attitudes related to the topic,

which is discussed from different angles. Every

student acts both as a source and as a collector

of certain information, becoming the agent of

interaction. Students notably improve their lan-

Poll your classmates Task 5

Each student acts out a short conversation with every student in the classroom

by (1) inviting everybody to do something

together and planning a weekend (the teacher

creates a calendar of events in the place where

the students live) or (2)asking directions to a

certain place.

Examples for Option 1:

1. Students look through the calendar of

events for the coming month. Each

student chooses one event and by mingling, invites everybody in the class

to attend it. How about going to

______? Or, Lets go to ______.

24

2014

Number

n g l i s h

e a c h i n g

o r u m

guage subskills (both grammar and vocabulary),

which are practiced and brushed up through

the simultaneous practice of all skills (reading,

speaking, listening, writing, and thinking). Taking notes in the course of mingling reinforces

those subskills and also helps students develop

the useful habit of listening and jotting down

the key ideas of what they hear.

In these tasks, the student motivation

for interaction is evoked by an information/

opinion gap as well as the need to prepare for

a subsequent, more challenging activity. The

diversity of information and opinions related

to the same subject matter enriches the learning environment and provides a basis for critical thinking. The following meaning-focused

mingles provide an argumentative approach

to problem solving as compared with a learning situation in which students work with a

single source of information.

pare four or five questions that help

them draw a well-grounded conclusion.

(The teacher can offer each student a

subtopic to avoid identical questions:

the Internet and learning foreign languages, school subjects, music, cooking, sports, traveling, jobs, shopping,

and making friends.)

2. Students first answer the questions

themselves and then decide if the questions are appropriate for achieving the

goal. They introduce changes, if necessary.

3. While mingling, students ask everybody in the classroom to answer their

questions.

4. Finally, students compare and analyze

the answers they have collected and

prepare a presentation of the findings.

Meaning-focused mingle 3

1. Each student gets a card with the names

of three pastimes; after analyzing the

three activities, they list the advantages

and disadvantages of each pastime.

Example activities are:

Meaning-focused mingle 1

1. Students first work individually with

different authentic materials (texts,

problems, situations, Internet sites, or

photos) by scrutinizing their personal

experiences for related information or

by creating questionnaires. They prepare for further interaction.

2. Students next interact with others by

sharing the information or by asking for opinions and facts. The work

is organized either as a walking-andtalking mingle or in rotating pairs and

requires taking notes. Working in rotating pairs, students sometimes are asked

to exchange their materials and then,

doing the task with a new partner, use

this new material for interaction. The

latter variation is suitable for students

with higher proficiency levels.

3. Students analyze the collected data

(classify, compare, identify pros and

cons, evaluate, look for evidence, and

finally come up with their own ideas).

4. Students present their findings and

discuss their opinions with the whole

class.

5. Students write summaries or draw conclusions.

bodybuilding, knitting, listening

to jazz

cross-country skiing, traveling,

collecting stamps

keeping a dog, writing poems,

hanging out with friends

dancing, reading detective stories, cooking

watching soap operas, gardening,

drawing

hitchhiking, listening to folk

music, designing clothes

Tip to the teacher: It makes sense to

offer some activities that are not very

popular among teens to promote a

variety of responses and give students

practice in talking about things they

like as well as things they may not like.

2. Students poll their classmates about

their attitude toward the three activities

to find out what they think about each

of the pastimes and why; then, while

mingling, students choose one of the

pastimes that a classmate dislikes and

persuades him or her to take it up.

3. Students report to the class on which

activities appeared to be the most and

Meaning-focused mingle 2

1. Students conduct a survey on the role

of the Internet in teens lives and pre-

n g l i s h

e a c h i n g

o r u m

Number

2014

25

the least popular and why. They point

out which activities their classmates

agreed to and did not agree to take up.

4. The whole class creates a list of the

most and least popular activities.

5. In groups, students decide on the

advantages of the least popular pastimes and the disadvantages of the

most popular activities.

6. Finally, students write an essay about

an activity that they have never done

but would like to try in the future.

These activities expand the situations and

contexts of learning while providing opportunities for students to integrate and recycle

their knowledge, skills, and subskills within

one topic and cross-topically. Learners deal

with a great variety of language contained in

the materials they work with and from their

fellow students. In addition, students are

encouraged to think as well as articulate and

negotiate their own ideas in English related

to a variety of subject matter. When students

mingle and interact, they are expected to

spontaneously respond to what they hear. All

this inevitably promotes the flexibility and

fluency of their English skills. Simultaneously,

the students improve their information-processing and social competences. The cumulative outcome of the student interaction is

their own well-grounded standpoint about

the issue under consideration and the ability

to argue for it in English.

At first, it is easier for students to reflect on

two or three opinions or facts where the controversy is on the surface. It is harder when

there is only one fact, opinion, or a generally

shared stereotype. Students get involved in

really heated discussions when the problem is

of great interest to them outside the classroom

or if they encounter a number of opposing

approaches to the problem.

While doing mingles, some students may

get off task and switch to their mother

tongue. Others may not take notes. To prevent such behaviors from the very start, the

teacher should explain that the success of the

follow-up activities will completely depend

on the outcome of the mingle. The preceding

instructions must draw the students attention

to what they will have to do later and how

they will use the information in the following

course of work (either in the lesson or while

doing their home assignment). They need to

see for themselves that keeping on task and

taking notes will save time and be beneficial

afterwards.

My observations show that mingles promote an improvement of grammar and

vocabulary competencies because every lan-

What do teaching experiences show?

As a school and university teacher, I have

been applying mingles for over 20 years. In

my teaching I have learned that collecting

materials for mingles takes time. Therefore,

teachers must use their time productively.

While surfing Internet sites, becoming familiar with various course books, observing

lessons or just living our everyday lives, we

should always be alert for those tasks, materials, and situations that could be transferred

into our classroom.

To support students with the language

they will use in the course of independent

mingle activities, we should stick to the following scaffolding strategies:

Offer mingles after whole-class preparatory work that may consist of

26

2014

Number

recycling the grammar, vocabulary, and

related experiences that the students

will rely on during mingles.

Provide prompts on the board, on an

overhead projector, or on the cards

handed out to those students who may

really need them.

Vary tasks and materials according to

student proficiency levels. Try to have

easier materials as well as more difficult

ones.

Occasionally repeat the same task or

text, changing the focus of the activity

in the mingle.

Allow time for students to reflect individually before and after meaningfocused mingles so they can sort out

their ideas and find more precise ways

to express them in English.

Provide an outline that guides the students steps in analyzing a problem as

well as graphic organizers to help them

see the links among facts.

Encourage students to store and repeatedly use the graphic organizers that

they have developed.

n g l i s h

e a c h i n g

o r u m

guage unit is frequently used by every student

in varied contexts and activities. The words

that students need for self-expression are easily remembered. On the whole, the learners

answers become linguistically more correct

and better grounded. Moreover, as my students have remarked, having practiced the

critical-thinking approach to problem solving

and discussions through mingles, they are able

to transfer it outside the classroom when communicating in their mother tongue.

well as outside the classroom. That is why we

should be ready to incorporate mingles into

our teaching without regret.

References

Borzova, E. V. 2008. Teachers as change agents:

Critical thinking tasks in a foreign language

classroom and reflections on printed materials.

In From brawn to brain: Strong signals in foreign

language education, ed. Seppo Tella, 2954.

Paper presented at the ViKiPeda-2007 Conference. Helsinki: University of Helsinki.

Edge, J. 1993. Essentials of English language teaching.

London: Longman.

Jonson, K. F. 2006. 60 strategies for improving reading comprehension in grades K8. Thousand

Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Klippel, F. 1984. Keep talking: Communicative fluency activities for language teaching. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Larsen-Freeman, D. 2012. From unity to diversity

... to diversity within unity. English Teaching

Forum 50 (2): 2227.

Rees, G. Teaching mixed-ability classes 1. 2003.

TeachingEnglish. London: British Council.

www.teachingenglish.org.uk/articles/teachingmixed-ability-classes-1

Robertson, C., and R. Acklam. 2000. Action plan

for teachers: A guide to teaching English. London:

BBC World Service. www.ingilizceci.net/miscellenaous/FurtherTeachTech.pdf

Seymour, D., and M. Popova. 2003. 700 classroom

activities: Instant lessons for busy teachers. Oxford:

Macmillan Education.

Vogt, M. E., and J. Echevarra. 2008. 99 ideas and

activities for teaching English learners with the

SIOP Model. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Conclusion

Provided that mingles are thoroughly

thought out and properly placed in the lesson plan, they contribute to the degree of the

student ownership of English as a personal

tool. Including mingles in a chain of tasks

on a regular basis in relation to every new

topic enhances students thinking, social and

English skills, and language competences.

They are learning to act in a more flexible

and natural way and to explore the environment through reading, listening, speaking,

and negotiating. Mingles allow teachers to

create numerous opportunities for students to

try out varied activities for themselves, and by

doing so they recycle, refine, and expand their

personal experiences. Encouraging students

to act effectively in the amplified learning

environment, teachers lead students beyond

what they know, can do well, or are already

interested in.

Students gradually become real agents of

what they are doing, people who are in charge

of the outcome, people who make their own

decisions and create their own meanings. It is

a personalized asset that is acquired thanks to

the whole person involvement based on the

interaction of thoughts, feelings, language,

and behavior. Tasks are not done solely for a

grade because learning needs are outweighed

by other needs. For example, the need to

learn English is replaced by the need to use it

while sharing information with an interested

listener, building relationships, and shaping

and discussing ones own opinions.

The use of mingles is the only class management strategy that allows every student to

do a lot of talking in the classroom, increasing

the quality of communicative competence in

English. In addition, mingle activities in the

classroom have the potential to considerably

improve the students relationships in class as

n g l i s h

e a c h i n g

o r u m

Elena Borzova is a professor in the English

Language Department at the Institute of

Foreign Languages of Petrozavodsk State

University, Russia. She has worked with

the Herzen State Pedagogical University

in St. Petersburg, the University of Eastern

Finland (Joensuu), and the College of

St. Scholastica, Minnesota. Her research

areas are teaching foreign languages at the

high school level and teacher training in the

field of foreign languages.

Number

2014

27

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Making Student Centered Teaching WorkDocumento10 pagineMaking Student Centered Teaching WorkCarmen FloresNessuna valutazione finora

- Summaries of Some Relevant ResearchesDocumento4 pagineSummaries of Some Relevant ResearchesAhmed AbdullahNessuna valutazione finora

- G.Mirkhodjaeva, The Teacher of Humanitarian-Economical Sciences of Turin Polytechnic University in TashkentDocumento7 pagineG.Mirkhodjaeva, The Teacher of Humanitarian-Economical Sciences of Turin Polytechnic University in TashkentFadhillah ZahraNessuna valutazione finora

- What Is Task-Based Learning?Documento4 pagineWhat Is Task-Based Learning?ALESSANDRA MARIA ASMAT CENTENONessuna valutazione finora

- Nurmasita Toindeng (A12222023)Documento5 pagineNurmasita Toindeng (A12222023)Yudith BadungNessuna valutazione finora

- The Internet TESL Journal KrishDocumento6 pagineThe Internet TESL Journal KrishShuzumiNessuna valutazione finora

- Teaching SpeakingDocumento9 pagineTeaching SpeakingBoe Amelia Nz100% (1)

- Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) - The Communicative ApproachDocumento5 pagineCommunicative Language Teaching (CLT) - The Communicative ApproachPAULA MONZONNessuna valutazione finora

- The Teacing of SpeakingDocumento13 pagineThe Teacing of Speakingveronika devinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Teaching Grammar IdeasDocumento5 pagineTeaching Grammar IdeasTammyNessuna valutazione finora

- A Role Play Activity With Distance Learners in An English Language ClassroomDocumento6 pagineA Role Play Activity With Distance Learners in An English Language ClassroomAudrey DiagbelNessuna valutazione finora

- Teacher and student talk in English classesDocumento15 pagineTeacher and student talk in English classesmoonamkaiNessuna valutazione finora

- LEARNING LOG 4 - July 4th 2023Documento6 pagineLEARNING LOG 4 - July 4th 2023angielescano1Nessuna valutazione finora

- The 3 Phases in A Communicative Oral TaskDocumento6 pagineThe 3 Phases in A Communicative Oral TaskJaqueline FoscariniNessuna valutazione finora

- Promoting Second Language Acquisition Through Classroom ConversationDocumento5 paginePromoting Second Language Acquisition Through Classroom Conversationnur istianaNessuna valutazione finora

- Ortiqov 3054 - 7428 1 2 20200925Documento5 pagineOrtiqov 3054 - 7428 1 2 20200925ajengjatryNessuna valutazione finora

- Proposal Literature Review MethodologyDocumento14 pagineProposal Literature Review Methodologyapi-610796909Nessuna valutazione finora

- Reading Week 1Documento19 pagineReading Week 1Romina SotoNessuna valutazione finora

- Task-Based Language Teaching (TBLT) - English Language Learners - Dual Language Learners - Multicultural Education Support - Language Lizard BlogDocumento4 pagineTask-Based Language Teaching (TBLT) - English Language Learners - Dual Language Learners - Multicultural Education Support - Language Lizard BlogBilel AbdellaouiNessuna valutazione finora

- Interactive ToolsDocumento25 pagineInteractive ToolsKristina PetkovaNessuna valutazione finora

- Sesión 01Documento47 pagineSesión 01Fer AlNessuna valutazione finora

- Differentiated InstructionDocumento26 pagineDifferentiated Instructionjpicard100% (1)

- THE ECLECTIC THEORY OF LANGUAGEDocumento2 pagineTHE ECLECTIC THEORY OF LANGUAGEiramshakoorNessuna valutazione finora

- Improve Speaking SkillsDocumento26 pagineImprove Speaking Skillsmekiiy78% (9)

- Methodological Principles of Language TeachingDocumento4 pagineMethodological Principles of Language Teachingcarolinaroman20020% (1)

- PTEG FunctionsNotions LevelA1Documento9 paginePTEG FunctionsNotions LevelA1Brem GutierrezNessuna valutazione finora

- Chap 1 MR TeslDocumento6 pagineChap 1 MR TeslJuni Artha SimanjuntakNessuna valutazione finora

- Task Based Language TeachingDocumento13 pagineTask Based Language TeachingSupansa SirikulNessuna valutazione finora

- Feliciano. Critical Paper#2.Documento8 pagineFeliciano. Critical Paper#2.pefelicianoNessuna valutazione finora

- (Nadeem Et Al 2012) Seating ArrangementDocumento10 pagine(Nadeem Et Al 2012) Seating ArrangementAlejandraMartínezNessuna valutazione finora

- Module 3. A Brief History of Language Teaching 2Documento10 pagineModule 3. A Brief History of Language Teaching 2Memy Muresan100% (1)

- Task and Project Work Apr 12Documento50 pagineTask and Project Work Apr 12api-251470476Nessuna valutazione finora

- Cooperative Learning Benefits ESL StudentsDocumento15 pagineCooperative Learning Benefits ESL StudentsReham IsmailNessuna valutazione finora

- أهداف وطرق تعليم مهارة الكلام لأغراض خاصDocumento8 pagineأهداف وطرق تعليم مهارة الكلام لأغراض خاصKhairul HudaNessuna valutazione finora

- Topic 2. EFLDocumento8 pagineTopic 2. EFLAntonioNessuna valutazione finora

- Language FunctionsDocumento5 pagineLanguage FunctionsEvelyn PerezNessuna valutazione finora

- Inclusion Whitepaper PRINT-croppedDocumento8 pagineInclusion Whitepaper PRINT-croppedChristian LoayzaNessuna valutazione finora

- Speaking Skills (Autosaved)Documento17 pagineSpeaking Skills (Autosaved)Nicole S. Jordan100% (2)

- Dagarin YawDocumento14 pagineDagarin YawUmairohNessuna valutazione finora

- Teaching Methods for Communicative LanguageDocumento6 pagineTeaching Methods for Communicative Languagedunia duniaNessuna valutazione finora

- Communicative Language Teaching - 2022 - PART IIDocumento33 pagineCommunicative Language Teaching - 2022 - PART IIChristina AgnadaNessuna valutazione finora

- 846-Article Text-1923-1-10-20201228Documento15 pagine846-Article Text-1923-1-10-20201228Khánh Linh PhanNessuna valutazione finora

- "Improving Vocabulary Ability by Using Comic": AbstractDocumento10 pagine"Improving Vocabulary Ability by Using Comic": AbstractekanailaNessuna valutazione finora

- UntitledDocumento7 pagineUntitledتينNessuna valutazione finora

- Makalah Kuliah: Home Hukum Ekonomi Komputer Keguruan Artikel Umum Kebidanan SkripsiDocumento4 pagineMakalah Kuliah: Home Hukum Ekonomi Komputer Keguruan Artikel Umum Kebidanan SkripsiErlangga WibawaNessuna valutazione finora

- Interactive Classroom vs. Traditional ClassroomDocumento4 pagineInteractive Classroom vs. Traditional ClassroomPulkit VasudhaNessuna valutazione finora

- TranslanguagingDocumento5 pagineTranslanguagingCheez whizNessuna valutazione finora

- Reaction PaperDocumento9 pagineReaction PaperMelchor Sumaylo PragaNessuna valutazione finora

- HBEL 3203 Teaching of Grammar: Fakulti Pendidikan Dan BahasaDocumento22 pagineHBEL 3203 Teaching of Grammar: Fakulti Pendidikan Dan BahasaMilly Hafizah Mohd KanafiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Teacher Talk in Classroom Interaction Performance: Journal of English Education and Literature Badan Penerbit UNM. 2007Documento10 pagineTeacher Talk in Classroom Interaction Performance: Journal of English Education and Literature Badan Penerbit UNM. 2007Suhar DimanNessuna valutazione finora

- TUGAS Bahasa InggrisDocumento4 pagineTUGAS Bahasa InggrisNhofita PadjidogiNessuna valutazione finora

- Ways of Motivating EFLDocumento8 pagineWays of Motivating EFLGabriela AlboresNessuna valutazione finora

- The Principles of Teaching SpeakingDocumento35 pagineThe Principles of Teaching SpeakingLJ Jamin CentinoNessuna valutazione finora

- 24 CL Moderna CP II OmenDocumento6 pagine24 CL Moderna CP II OmenAlexa BlankaNessuna valutazione finora

- GlossaryDocumento3 pagineGlossaryAnonymous ZGYGuaNessuna valutazione finora

- JURNAL BAHASA INGGRIS SemiinarDocumento8 pagineJURNAL BAHASA INGGRIS SemiinarLimaTigaNessuna valutazione finora

- Using Pair Activity To Keep Students Active in Learning EnglishDocumento14 pagineUsing Pair Activity To Keep Students Active in Learning EnglishMuh ZulzidanNessuna valutazione finora

- A Triangular Approach To Motivation in CAALL - 2007Documento21 pagineA Triangular Approach To Motivation in CAALL - 2007aamir.saeedNessuna valutazione finora

- Contribution To Mobile-Enhanced English Language Learning - December 2013Documento30 pagineContribution To Mobile-Enhanced English Language Learning - December 2013aamir.saeedNessuna valutazione finora

- Complexity Theory and CALL Curriculum - May 2014Documento7 pagineComplexity Theory and CALL Curriculum - May 2014aamir.saeedNessuna valutazione finora

- Vowelizing English Consonant Clusters With Arabic Vowel Points Harakaat-Does It Help-July 2014Documento20 pagineVowelizing English Consonant Clusters With Arabic Vowel Points Harakaat-Does It Help-July 2014aamir.saeed100% (1)

- PREPRINT Gbladoption HicssDocumento10 paginePREPRINT Gbladoption Hicssaamir.saeedNessuna valutazione finora

- Bussey, Bandura. Social Cognitive Theory of Gender Dev and DiffDocumento38 pagineBussey, Bandura. Social Cognitive Theory of Gender Dev and DiffKateřina Capoušková100% (2)

- Acoustical Analysis of Vowel Duration in Palestinian Arab Speakers - 2014Documento5 pagineAcoustical Analysis of Vowel Duration in Palestinian Arab Speakers - 2014aamir.saeedNessuna valutazione finora

- Computer Assisted Language Learning - July 2013Documento12 pagineComputer Assisted Language Learning - July 2013aamir.saeedNessuna valutazione finora

- Vowelsystems of Quantity Languages Compared - Arabic Dialects and Other Languages - 2014Documento10 pagineVowelsystems of Quantity Languages Compared - Arabic Dialects and Other Languages - 2014aamir.saeedNessuna valutazione finora

- Lexical and Language Modeling of Diacritics - Feb 2014Documento72 pagineLexical and Language Modeling of Diacritics - Feb 2014aamir.saeedNessuna valutazione finora

- 2829 11123 1 PBDocumento5 pagine2829 11123 1 PBaamir.saeedNessuna valutazione finora

- 680 1262 1 SMDocumento12 pagine680 1262 1 SMaamir.saeedNessuna valutazione finora

- Continuum Companion PhonologyDocumento540 pagineContinuum Companion Phonologyaamir.saeed100% (1)

- 2810 11050 1 PBDocumento7 pagine2810 11050 1 PBaamir.saeedNessuna valutazione finora

- 23-02-14 DU Enlish Language ConfDocumento1 pagina23-02-14 DU Enlish Language Confaamir.saeedNessuna valutazione finora

- Brendan Bartram Attitudes To Modern Foreign Language Learning Insights From Comparative Education Continuum 2010Documento209 pagineBrendan Bartram Attitudes To Modern Foreign Language Learning Insights From Comparative Education Continuum 2010aamir.saeedNessuna valutazione finora

- A Targeted Review of CAL - November 2013Documento14 pagineA Targeted Review of CAL - November 2013aamir.saeedNessuna valutazione finora

- B094 FINAL Aston University A4 Report - 2column - V3Documento29 pagineB094 FINAL Aston University A4 Report - 2column - V3Edwiin RamirezNessuna valutazione finora

- IE TC 2010: Students' Motivation Towards Computer Use in Efl LearningDocumento3 pagineIE TC 2010: Students' Motivation Towards Computer Use in Efl Learningaamir.saeedNessuna valutazione finora

- Gen Teach StrategiesDocumento5 pagineGen Teach StrategiesCutty Batson100% (1)

- IE TC 2010: Students' Motivation Towards Computer Use in Efl LearningDocumento3 pagineIE TC 2010: Students' Motivation Towards Computer Use in Efl Learningaamir.saeedNessuna valutazione finora

- Pedagogical Corpora As A Means To Reuse Research Datat in Teacher Training - July 2014Documento6 paginePedagogical Corpora As A Means To Reuse Research Datat in Teacher Training - July 2014aamir.saeedNessuna valutazione finora

- Tirf Olte One-Pagespread 2013Documento112 pagineTirf Olte One-Pagespread 2013aamir.saeedNessuna valutazione finora

- Choose Use Booklet FADocumento22 pagineChoose Use Booklet FAOkaNessuna valutazione finora

- WWW - Squ.edu - Om - Portals - 28 - Research Committee - Call For Springer Book ChapterDocumento3 pagineWWW - Squ.edu - Om - Portals - 28 - Research Committee - Call For Springer Book Chapteraamir.saeedNessuna valutazione finora

- Adverbs of Frequency Worksheet 1Documento1 paginaAdverbs of Frequency Worksheet 1hama0% (1)

- Language Teaching and Learning in ESL ClassroomDocumento268 pagineLanguage Teaching and Learning in ESL Classroomaamir.saeed100% (16)

- Parts PF SpeechDocumento16 pagineParts PF SpeechN Johana EspinozaNessuna valutazione finora

- Eltconf15 Conference Brochure 2015aDocumento9 pagineEltconf15 Conference Brochure 2015aaamir.saeedNessuna valutazione finora

- Conceptual Work and The 'Translation' ConceptDocumento31 pagineConceptual Work and The 'Translation' Conceptehsaan_alipourNessuna valutazione finora

- Science EducationDocumento6 pagineScience EducationAnonymous e62fGNNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson 2 - Planning ImotionDocumento3 pagineLesson 2 - Planning Imotionapi-335773558Nessuna valutazione finora

- Group DiscussionDocumento5 pagineGroup DiscussionPrince RathoreNessuna valutazione finora

- Managing High PotentialsDocumento5 pagineManaging High PotentialsDũng LưuNessuna valutazione finora

- Guia Del Estudiante Plataforma MYELT 2Documento15 pagineGuia Del Estudiante Plataforma MYELT 2Renato Farje ParrillaNessuna valutazione finora

- Cu 31924081220968Documento176 pagineCu 31924081220968Jerrin GeorgeNessuna valutazione finora

- Esol Small Group LP 2Documento4 pagineEsol Small Group LP 2api-704735280Nessuna valutazione finora

- Characteristics of A Highly Effective Learning EnvironmentDocumento4 pagineCharacteristics of A Highly Effective Learning Environmentapi-257746864Nessuna valutazione finora

- Thematic Unit QuestionsDocumento2 pagineThematic Unit Questionsapi-508881242Nessuna valutazione finora

- Tinywow - PhysicalEducation12 - 2022 (1) - 41424952 - 9Documento46 pagineTinywow - PhysicalEducation12 - 2022 (1) - 41424952 - 9HwhaibNessuna valutazione finora

- Nursing Process in CHNDocumento38 pagineNursing Process in CHNHannah Lat VillavicencioNessuna valutazione finora

- Unravelling The Myth/Metaphor Layer in Causal Layered AnalysisDocumento14 pagineUnravelling The Myth/Metaphor Layer in Causal Layered AnalysismarkusnNessuna valutazione finora

- The-Effectiveness of Audio-Visual Aids in Grade 7 Students Attention Span in Their Academic-Learning.Documento62 pagineThe-Effectiveness of Audio-Visual Aids in Grade 7 Students Attention Span in Their Academic-Learning.Eljan SantiagoNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction To Information Systems 6th Edition Rainer Solutions Manual DownloadDocumento18 pagineIntroduction To Information Systems 6th Edition Rainer Solutions Manual DownloadDavid Johansen100% (22)

- I. Multiple Choice: Read and Analyze Each Item Carefully. Choose The Letter of The Correct Answer and Write It On Your Answer SheetDocumento3 pagineI. Multiple Choice: Read and Analyze Each Item Carefully. Choose The Letter of The Correct Answer and Write It On Your Answer Sheetjennalyn caracasNessuna valutazione finora

- G9Documento14 pagineG9ethanjeon090622Nessuna valutazione finora

- T-Tess GoalsDocumento2 pagineT-Tess Goalsapi-414999095Nessuna valutazione finora

- Handout 1 EdflctDocumento4 pagineHandout 1 Edflctsageichiro8Nessuna valutazione finora

- ECA2+ - Tests - Grammar Check 2.4BDocumento1 paginaECA2+ - Tests - Grammar Check 2.4BAlina SkybukNessuna valutazione finora

- Dries Daems - Social Complexity and Complex Systems in Archaeology (2021, Routledge) - Libgen - LiDocumento264 pagineDries Daems - Social Complexity and Complex Systems in Archaeology (2021, Routledge) - Libgen - LiPhool Rojas CusiNessuna valutazione finora

- Learning BehaviorDocumento47 pagineLearning Behavioraliyan hayderNessuna valutazione finora

- Media and Information Literacy Virtual ExaminationDocumento17 pagineMedia and Information Literacy Virtual ExaminationMam Elaine AgbuyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Metaphors of Memory A History of Ideas About The M PDFDocumento3 pagineMetaphors of Memory A History of Ideas About The M PDFStefany GuerraNessuna valutazione finora

- Top Student's Transcript from University of TripoliDocumento7 pagineTop Student's Transcript from University of TripoliAlaNessuna valutazione finora

- Additive and Multiplicative Patterns LessonDocumento4 pagineAdditive and Multiplicative Patterns Lessonapi-444336285Nessuna valutazione finora

- Assessment Commentary EdtpaDocumento4 pagineAssessment Commentary Edtpaapi-252181836Nessuna valutazione finora

- Machine Learning: The New 'Big Thing' For Competitive AdvantageDocumento30 pagineMachine Learning: The New 'Big Thing' For Competitive Advantagemadhuri gopalNessuna valutazione finora

- Tle Reflection ChloeDocumento1 paginaTle Reflection ChloefloridohannahNessuna valutazione finora

- Machine Learning Vs StatisticsDocumento5 pagineMachine Learning Vs StatisticsJuan Guillermo Ferrer VelandoNessuna valutazione finora