Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

A Functional and Symbolic Perspective To Branding Australian SME Wineries

Caricato da

Thinagaran SubbramaniamTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

A Functional and Symbolic Perspective To Branding Australian SME Wineries

Caricato da

Thinagaran SubbramaniamCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Journal of Product & Brand Management

A functional and symbolic perspective to branding Australian SME wineries

James Mowle Bill Merrilees

Article information:

Downloaded by UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN QUEENSLAND At 06:44 03 January 2015 (PT)

To cite this document:

James Mowle Bill Merrilees, (2005),"A functional and symbolic perspective to branding Australian SME wineries", Journal of

Product & Brand Management, Vol. 14 Iss 4 pp. 220 - 227

Permanent link to this document:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/10610420510609221

Downloaded on: 03 January 2015, At: 06:44 (PT)

References: this document contains references to 29 other documents.

To copy this document: permissions@emeraldinsight.com

The fulltext of this document has been downloaded 3373 times since 2006*

Users who downloaded this article also downloaded:

Subodh Bhat, Srinivas K. Reddy, (1998),"Symbolic and functional positioning of brands", Journal of Consumer Marketing, Vol.

15 Iss 1 pp. 32-43 http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/07363769810202664

Gillian Horan, Michele O'Dwyer, Siobhan Tiernan, (2011),"Exploring management perspectives of branding in service SMEs",

Journal of Services Marketing, Vol. 25 Iss 2 pp. 114-121 http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/08876041111119831

Frank B.G.J.M. Krake, (2005),"Successful brand management in SMEs: a new theory and practical hints", Journal of Product

& Brand Management, Vol. 14 Iss 4 pp. 228-238 http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/10610420510609230

Access to this document was granted through an Emerald subscription provided by 405406 []

For Authors

If you would like to write for this, or any other Emerald publication, then please use our Emerald for Authors service

information about how to choose which publication to write for and submission guidelines are available for all. Please visit

www.emeraldinsight.com/authors for more information.

About Emerald www.emeraldinsight.com

Emerald is a global publisher linking research and practice to the benefit of society. The company manages a portfolio of

more than 290 journals and over 2,350 books and book series volumes, as well as providing an extensive range of online

products and additional customer resources and services.

Emerald is both COUNTER 4 and TRANSFER compliant. The organization is a partner of the Committee on Publication Ethics

(COPE) and also works with Portico and the LOCKSS initiative for digital archive preservation.

*Related content and download information correct at time of download.

A functional and symbolic perspective to

branding Australian SME wineries

James Mowle and Bill Merrilees

Downloaded by UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN QUEENSLAND At 06:44 03 January 2015 (PT)

Department of Marketing, Griffith Business School, Griffith University, Gold Coast, Australia

Abstract

Purpose This study proposes investigating the branding of small to medium-sized enterprise (SME) wineries in an Australian context. By taking a

qualitative approach, the theory building research seeks further to understand branding from the perspective of the SME winery, and in doing so, go

some way in addressing the current deficit in the literature.

Design/methodology/approach Bhat and Reddys conceptualisation of brand functionality and symbolism is used as a branding framework to

underlie the research. A multiple case study design was adopted as a research method to provide case data on eight SME wineries. Data were collected

through in-depth interviews with the owner/manager of each winery, direct observation and document analysis.

Findings The findings are presented in the form a model of SME winery branding, which, in addition to distinguishing two approaches to branding,

highlights the functional and symbolic values inherent in the brand. The findings endorse the notion that brands can simultaneously have both

functional and symbolic appeal. More radically, the emergent model suggests interdependence between the functional and symbolic properties of

branding.

Practical implications Practically, the findings highlight the importance of developing the symbolic values associated with the brand, which

represent a more sustainable competitive advantage.

Originality/value By establishing a tentative theory on SME winery branding, this study has begun to address the current deficit in wine marketing

literature and has set a foundation for further research.

Keywords Branding, Small-to-medium-sized enterprises, Winemaking, Australia

Paper type Research paper

future (Beverland, 2000; Getz, 2000; Lockshin, 1997).

Indeed, Reid (2002, p. 37) notes that the development of

strong and desirable brands will be paramount to the future

success of all wine companies. Despite this general

consensus, it appears that little empirical research has been

undertaken on this aspect of the wine industry, particularly

regarding small and medium-sized (SME) wineries.

Acknowledging this and many other gaps in current

literature, academics have commented on the need for more

research to be undertaken on all aspects of the industry,

particularly through case studies and comparisons of

successful wineries, to further the knowledge in the area

(Dowling and Getz, 2001; Hall et al., 2000; Getz, 2000).

Despite the vital role that brands play in the successful

marketing of wine, there appears to be a paucity of empirical

research into branding in the wine industry. Beyond the

recommendation that wineries place an increased emphasis

on branding in their strategy, very few studies detail the

concept of branding from the perspective of the winery.

Additionally, marketing related inquiry focusing specifically

on SME wineries has been minimal. Considering that 85 per

cent of wineries in Australia can be classified as small, and a

further 4 per cent classified as medium (ACIL, 2002), the

lack of research regarding SME wineries appears concerning.

This study aims to contribute to the research that is needed to

fill a significant gap in the literature concerning marketing and

branding of SME wineries. Guided by the research question

How do small and medium-sized wineries in Southeast

Queensland and the Canberra District approach branding in

their marketing?, this research inductively seeks further to

understand branding from the perspective of the SME winery.

An executive summary for managers and executive

readers can be found at the end of this article.

Introduction

The Australian wine industry has witnessed phenomenal

growth in the number of wineries in recent years, growing

from 530 in 1990 to more than 1,600 presently.

Accompanying this growth has been a trend of market

domination, with 94 per cent of Australias production now

accounted for by just 20 companies. Furthermore, retail

consolidation led by the Australian supermarket chains is

leaving the remaining wineries, of which 85 per cent are small

producers, struggling to obtain shelf space in liquor stores

(Evans, 2002). These characteristics have made the

Australian market highly fragmented and increasingly

competitive, forcing many wineries to place increasing

emphasis on cellar door sales for survival (ONeill et al.,

2002; Getz, 2000).

This competitive environment has prompted many

academics to comment on the need for increased emphasis

on marketing, particularly branding, to ensure success in the

The Emerald Research Register for this journal is available at

www.emeraldinsight.com/researchregister

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at

www.emeraldinsight.com/1061-0421.htm

Journal of Product & Brand Management

14/4 (2005) 220 227

q Emerald Group Publishing Limited [ISSN 1061-0421]

[DOI 10.1108/10610420510609221]

220

Downloaded by UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN QUEENSLAND At 06:44 03 January 2015 (PT)

A functional and symbolic perspective to branding

Journal of Product & Brand Management

James Mowle and Bill Merrilees

Volume 14 Number 4 2005 220 227

Literature review

Conceptual framework

The process of branding has been around for centuries as a

means to distinguish the goods of one producer from those of

another (Keller, 2003). Although various definitions appear in

the literature, a brand can essentially be described as an

identifiable product, service, person or place, augmented in

such a way that the buyer or user perceives relevant, unique,

sustainable added values which match their needs most

closely (de Chernatony, 2001, p. 9). This definition of a

brand highlights the added values that the consumer perceives

inherent in a brand. Numerous discussions in the literature

separate these added values into two, with a brand delivering

functional value and symbolic value (Bhat and Reddy, 1998;

de Chernatony et al., 2000; Belen del Rio et al., 2001;

Meenaghan, 1995; Park et al., 1986; Travis, 2000).

Functional values associated with a brand relate to the

tangible, rationally assessed product performance benefits

that satisfy consumers practical needs (de Chernatony et al.,

2000; Bhat and Reddy, 1998). Although it is important to

promote functional differences in the brand, de Chernatony

et al. (2000) note that symbolic values are more sustainable as

a form of differentiation than functional values. Symbolic

values associated with the brand, also termed emotional

values, relate to the intangible feelings and symbolic benefits

that satisfy the consumers self-expression needs (Bhat and

Reddy, 1998). Meenaghan (1995) additionally comments that

it is the symbolic values inherent in a brand that send social

signals on behalf of their consumers. Bhat and Reddy (1998)

further highlight the multidimensional nature of brand

symbolism, asserting that brands do not have to be

positioned as prestige to tap into the symbolic needs of the

consumer. Hence, the symbolic values may relate to a

consumers personality or self concept that includes

fashionability, freedom of expression, prestige and

exclusivity (Bhat and Reddy, 1998).

Park et al. (1986) first proposed that a brand concept can

either be functional or symbolic, with brands positioned as

either, but not both. Bhat and Reddy (1998) further advanced

the theory by proposing that functionality and symbolism are

separate components, with it being possible for a brand to

have both symbolic and functional appeal. Therefore, it

appears that consumers do not have any trouble accepting

brands that have both symbolic and functional appeal (Bhat

and Reddy, 1998). De Chernatony et al. (2000), who propose

that the value of a brand is a multidimensional construct

which includes both functional and symbolic benefits as

perceived by consumers, further support Bhat and Reddys

(1998) findings.

As wine has increasingly been regarded as a lifestyle product

(WFA, 2002), it seems beneficial to embrace the concept of

symbolic value that relates to consumers self expression needs

in research on branding in the wine industry. Apart from Getz

(2000), who notes that a brand requires a blending of

functional and symbolic values, Lockshin et al. (2000) appear

to be the only authors who discuss a brands functional and

symbolic values in the context of the wine industry. Lockshin

et al. (2000), without an apparent empirical basis, adopt Bhat

and Reddys (1998) proposition that brands can

simultaneously have both functional and symbolic appeal

and recommend to practitioners that equal importance be

placed on developing both the functional differences and the

symbolic values of wine brands.

In theory building research, no matter how inductive the

approach, a prior view is needed of the general constructs or

categories that are to be studied (Voss et al., 2002). Miles and

Huberman (1994) suggest doing this through construction of

a conceptual framework. Such a framework underlies the

research by explaining, either graphically or in narrative form,

the main things that are to be studied and compels the

researcher to think carefully and selectively about the

constructs and variables to be included in the study (Voss

et al., 2002). Hence, the conceptual framework guides the

theory development process by providing a tentative

framework within which it is anticipated that the questions,

theory and data fit together (Fawcett and Downs, 1992).

Much of the extant literature relating to winery operations

and marketing generally distinguishes two types of wineries:

those who focus predominantly on production and those who

have an additional focus on marketing (Beverland, 2000;

Getz, 2000; Reid, 2002; Shelton, 2001). Shelton (2001)

terms the two general types product driven wineries and

market driven wineries. Getz (2000) presents the most

concise description of these two general types. He notes that a

portion of the wine industry is focused on production, while

other wineries have a dedicated marketing strategy in addition

to ensuring a focus on production.

The two-type separation of winery operations described

above forms the basis of the conceptual framework. Shown in

Figure 1, the model presents a tentative prediction of the

emergence of two approaches to branding based on branding

sophistication.

The first predicted type that guided the investigation is one

with a low level of branding sophistication. Based partially on

previous descriptions in the literature of product driven

wineries, this typology is characterised with a dominant focus

on the production of wine and a relatively limited approach to

marketing and promotion aspects such as branding.

The second predicted type that guided the investigation is

one with a higher level of branding sophistication. Based

partially on previous descriptions in the literature of wineries

with both a focus on production and a dedicated marketing

strategy, this typology is characterised with an increased focus

on marketing and promotion aspects such as branding.

The case research method, anchored in the qualitative

research domain, was used to reveal the details and profile the

characteristics of each of the two typologies. Bhat and Reddys

(1998) brand theory, discussed previously in chapter two, was

used to interpret this information in terms of the functional

Figure 1 Conceptual framework: typology of two approaches to SME

winery branding

221

A functional and symbolic perspective to branding

Journal of Product & Brand Management

James Mowle and Bill Merrilees

Volume 14 Number 4 2005 220 227

and symbolic values of each case brand. Additionally, it is

important to highlight the tentative nature of the conceptual

model. Establishing the possibility of two general approaches

to branding provided a frame of reference to focus on certain

themes throughout the investigation. Therefore the two-type

typology was open to modification during the case research

process, depending on the emergent findings.

Case selection

The population of interest for this research situation consisted

of small and medium- sized wineries that operate a cellar door

sales outlet in Southeast Queensland and the Canberra

District. A winery is described by ACIL (2002) as being small

or medium if it produces between 1,500 and 75,000 cases of

wine a year. As advocated by Eisenhardt (1989), cases were

carefully selected for theoretical, not statistical reasons. A

maximum variation sampling method selected cases to fill

theoretical categories and seek diversity in three critical

categories: winery size; winery age; and the facilities provided

at the cellar door. Cases were selected from two separate areas

of Australia in order to achieve further variation in the

characteristics of the wineries. Furthermore, due to the

relative infancy of the Queensland wine industry, more

established wineries were incorporated into the research by

investigating Canberra District wineries.

A total of eight wineries were investigated as part of the

study, five from Southeast Queensland and three from the

Canberra District. Throughout data collection, Eisenhardts

(1989) concept of theoretical saturation guided the decision

to discontinue adding cases to the study. Theoretical

saturation prescribes that the adding of cases can

discontinue when incremental learning is minimal because

the phenomena observed has already seen before (Eisenhardt,

1989). Therefore, while also considering the issue of time

constraints, the decision to discontinue adding cases after the

eighth case study was made as the incremental learning was

expected to be minimal.

Downloaded by UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN QUEENSLAND At 06:44 03 January 2015 (PT)

Research method

Qualitative case study

Being an exploratory study into an under-researched topic

area, the research employed qualitative, theory building

techniques to understand branding further from the

perspective of the SME winery owner or manager. The

research closely adhered to the Eisenhardt (1989)

methodological framework of building theory from case

study research. Such a framework requires clear research

questions, selecting cases in a purposeful way, using semistructured protocols, overlapping data collection and data

analysis and analysing cases on a within-case and across-case

basis.

Yin (2003, p.13) describes a case study as:

[. . .] an empirical inquiry that investigates contemporary phenomena within

its real-life context, especially when the boundaries between the phenomena

and context are not clearly evident.

Such an approach enabled a holistic perspective to be taken

on the branding practices of the wineries with all of the

potentially rich and meaningful characteristics of a marketing

program being examined (Yin, 2003). The case study method

typically incorporates numerous data sources to provide a

fuller picture of the business unit under study, but often relies

primarily on personal interviews and unobtrusive observation

during data collection (Bonoma, 1985).

Data collection

Data were collected through in-depth interviews with the

owner/manager of each winery, direct observation and

document analysis. The use of these three sources of

evidence provided a more complete picture of each case

under investigation and enabled the corroboration of any fact

or finding for which there were reservations about (Yin,

2003).

A case study protocol and a semi-structured interview

protocol were used to help address reliability issues and

ensure a degree of systemisation in the procedures and

questions over the multiple cases. Each interview generally

lasted for approximately an hour, but ranged from 40 minutes

to two hours. The interviews remained open ended and

assumed a conversational manner, while ensuring the

discussion addressed the set of questions outlined in the

protocol. Questions were kept deliberately broad to allow

respondents as much freedom in their answers as possible. To

ensure that all ideas and insights of the interviewees were

noted accurately, a tape recorder was used in addition to note

taking during the interview process. Data were transcribed

from the cassette tapes with the transcripts sent back to

participants to check for accuracy and clarify any confusion or

inconsistencies.

Case study design

Case study designs can be categorised as single or multiple

case designs as well as either holistic or embedded designs

(Yin, 2003). A multiple, holistic case study design was used to

investigate the branding of eight SME wineries in two regions

of Australia: Southeast Queensland and the Canberra

District. The decision to use a holistic approach to the case

design was based largely on the small nature of the wineries

under investigation, limiting the division of the organisation

into smaller sub-units. The decision to adopt a multiple case

study design was based on the contrast and diversity that is

achieved from investigating multiple cases. Eisenhardt (1989)

notes that multiple-case studies are a powerful means to

create theory, with the contrast and diversity contributing to

the richness of the resulting theory.

Methodological soundness

An important factor in any research design is establishing

methodological soundness. Strong measures can be taken to

build rigour into case study research at the research design,

data collection and data analysis stages (Parkhe, 1993). In

addressing validity and reliability, Yin (2003) presents several

case study tactics for dealing with these issues. The tactics

used in this research to address the issues of construct validity,

internal validity, external validity and reliability are presented

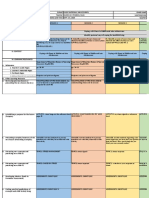

in Table I.

Data analysis

Data analysis and data collection overlapped, with cases being

analysed individually before incrementally analysing across

the cases throughout the data collection process. Miles and

Hubermans (1994) matrix analysis technique and Yins

(2003) concept of pattern matching were used to analyse the

case study evidence and systematically compare the emergent

themes, concepts and theory with the case data.

222

A functional and symbolic perspective to branding

Journal of Product & Brand Management

James Mowle and Bill Merrilees

Volume 14 Number 4 2005 220 227

Table I Case study tactics for methodological soundness

Tests

Case study tactic

Phase of research in which tactic occurs

Construct validity

Use of multiple sources of evidence

Establish chain of evidence

Have key informants review interview transcripts

Pattern matching

Address rival explanations

Use of multiple case design

Replication logic using analytical generalisation

Case study protocol

Semi-structured interview protocol

Develop case study database

Data collection

Data collection

Data collection

Data analysis

Data analysis

Research design

Research design

Data collection

Data collection

Data collection

Internal validity

External validity

Reliability

Downloaded by UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN QUEENSLAND At 06:44 03 January 2015 (PT)

Source: Yin (2003)

Findings

1

2

3

4

5

6

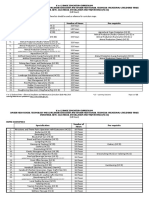

The characteristics of each of the eight cases are summarised

in Table II. A range of ages, sizes, and ways of doing business

were witnessed across all cases.

Analysis of the case study data resulted in the emergence of

a model of SME winery branding, shown in Figure 2.

Detailed within the model are two approaches that the

wineries under investigation were seen to employ to brand

their winery. The first approach has been termed product

driven branding, with the second approach termed marketing

driven branding. Three of the wineries investigated were

found to implement product driven branding, with the

remaining five wineries investigated found to implement

marketing driven branding. In addition to distinguishing two

approaches to branding, the model also details the functional

and symbolic values inherent in the SME winery brand.

Although differences emerged as to how the wineries

approached their branding, all of the wineries were found to

have several common features that acted as a foundation to

their branding. The combination of these features can be

regarded as essentially inherent in the nature of SME wineries

and acting as a generic base common to both approaches to

branding, illustrated in Figure 2. Six common factors were

found to make up this foundation:

Product-driven branding

Wineries identified with product-driven branding had their

main form of differentiation, and therefore their brand, based

around the wine itself. Therefore, beyond the generic base,

the product created the brand and the brand signified the

wine. The wineries identified with product-driven branding

displayed several common characteristics that differentiated

them from their marketing driven counterparts. Considered

to be common traits of the wineries with product driven

branding, these characteristics are:

.

the focus at the cellar door being on the wine;

.

personal approach where visitors can meet the winemaker;

and

.

a limited amount of marketing and promotion.

As illustrated in Figure 2, the wineries with the productdriven approach to branding exhibited a brand with dominant

functional values that arose from characteristics of the wine,

such as the quality, taste, variety or value for money. The

symbolic values associated with the brand were also tied to the

product component, and therefore had a strong

interconnection with the functional values. Providing an

illustration of the product driven approach to branding is the

following quote from the winemaker of Winery 6:

Table II Descriptions of case study wineries

Case no.

Region

Annual production

(cases)

Facilities

Winery 1 Southeast Queensland

2,500

Winery 2 Southeast Queensland

4,500

Winery 3 Southeast Queensland

900

Winery 4 Canberra District

Winery 5 Canberra District

Winery 6 Canberra District

3,500

1,500

4,000

Winery 7 Southeast Queensland

3,000

Winery 8 Southeast Queensland

60,000

producing a premium product;

conveying an image of quality wines;

using a name and symbol to represent the winery;

forming business relationships and networks;

participating in regional events, festivals and shows; and

providing friendly service at the cellar door.

Were very quality focused and quality driven . . . the wines are not cheap . . .

its part of how we promote ourselves to be of high quality and maybe hard to

find, but theyre worth the search. Thats the kind of image that we like to

maintain (winemaker, Winery 6).

Cellar door

Celler door

Dining facilities

Celler door

Dining facilities

Celler door

Dining facilities

Cellar door

Cellar door

Celler door

Dining facilities

Celler door

Dining facilities

As described by the winemaker of Winery 6, the brand

exhibited quality-focused product characteristics (product

component), resulting in the wine being high quality

(functional value), high priced and perhaps hard to find.

Such product characteristics resulted in an image of prestige

and exclusivity (symbolic values).

Marketing-driven branding

Wineries identified with marketing driven branding developed

their brand with a more holistic approach that encompassed

223

A functional and symbolic perspective to branding

Journal of Product & Brand Management

James Mowle and Bill Merrilees

Volume 14 Number 4 2005 220 227

Downloaded by UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN QUEENSLAND At 06:44 03 January 2015 (PT)

Figure 2 Two emergent approaches to branding: product driven branding and marketing driven branding

Discussion and conclusion

the experience at the winery as well as the wine. Therefore,

the marketing driven approach comprises an experiential

component in addition to the generic base for branding and

the product component.

Largely resulting from a marketing driven desire to create a

total wine experience, the experience component further

differentiated the SME winerys brand. Consequently, the

experience contributed to a more holistic brand for the winery

that encompassed an experience for visitors in addition to the

wine.

The wineries identified with marketing driven branding

displayed several common characteristics that differentiated

them from their product-driven counterparts. Considered to

be common traits of the wineries with marketing driven

branding, these characteristics are:

.

a focus at the cellar door on an experience;

.

a greater emphasis on marketing and promotion; and

.

extending the product range to merchandise.

Two main findings of the research contribute to the better

understanding of how SME wineries approach branding in

their marketing:

1 the emergence of two approaches that the SME wineries

took for branding; and

2 the identification of functional and symbolic values

inherent in the SME winery brand.

The identification of two approaches to branding, although

not discussed previously in relation to brand development,

appears to be supported by literature discussing the

operational focus of wineries. As established previously, the

literature relating to winery operations generally distinguishes

two types of wineries: those who focus predominantly on

production and those who have an additional focus on

marketing. The identification of wineries with a product

driven approach to branding appears to identify with AliKnight and Charters (1999)regard for some wineries being

predominantly focused on wine production. However, the

findings of this study conflict with Ali-Knight and Charters

(1999) view that these wineries have little understanding of

marketing. Several SME wineries identified to have a product

driven approach to branding were found to have a sound

understanding of marketing and how to brand their wines

effectively. The identification of wineries with a marketing

driven approach to branding appears to identify with Getzs

(2000) regard for some wineries to have a dedicated

marketing strategy that incorporates tourism to build brand

equity. Building on this description, the current research has

highlighted the role the experience at the winery, and its

associated symbolic values, plays in the in the development of

the brand.

The identification of functional and symbolic values

associated with the SME winery brand is well supported by

the current theoretical framework on brand functionality and

symbolism. Bhat and Reddys (1998) theoretical framework

asserts that a brand represents both functional performance

attributes and intangible symbolic values for the consumer.

Although the wineries identified with marketing driven

branding still had prevalent functional values to their brand,

they also had a greater symbolic value to the brand. Rather

than being tied to the product, the symbolic value was largely

developed through the experiential component of the

branding.

Illustrating the incorporation of the experience into the

brand is the following comment from the marketing manager

of Winery 8.Its all about enjoying the wine. So the views, the

grounds . . . its enjoying life. So every time you pick up a

bottle of [Winery 8] wine, you think Im going to have a

good time, its about fun and enjoyment. He [the

winemaker] wants to give them an easy drinking Queensland

wine (marketing manager, Winery 8).As described by the

marketing manager of Winery 8, the winery provided a laidback, enjoyable experience at the winery (experience

component), resulting in the feelings of fun, enjoyment and

having a good time (symbolic value) being associated with the

brand. Such added values are reinforced by the easy-to-drink

characteristics of the wine (functional value) and its associated

emotional values of enjoyment.

224

Downloaded by UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN QUEENSLAND At 06:44 03 January 2015 (PT)

A functional and symbolic perspective to branding

Journal of Product & Brand Management

James Mowle and Bill Merrilees

Volume 14 Number 4 2005 220 227

Both of the emergent approaches to branding resulted in

functional and symbolic values associated with the SME

winery brand, a finding that is supported by Bhat and Reddys

(1998) notion that brands can simultaneously have both

functional and symbolic appeal.

Regardless of whether a SME winery implements a strategy

of product driven branding or marketing driven branding,

skills are needed to identify and manage the desired functional

and symbolic values of the SME winery brand. With

de Chernatony et al. (2000) indicating that the symbolic

values are a more sustainable form of differentiation than

functional values, an emphasis on developing the symbolism

inherent in the brand should be rewarded with more

sustainable differentiation.

findings support Getzs (2000) notion that there is more than

one possible strategy for wineries to adopt for success.

The case findings and the emergent model also present a

tentative theory on how to enhance the branding element of

the SME winery. Illustrated by the differences in the two

approaches, the framework presents a multi-stage process of

branding which builds on the functional aspect of the wine

with an experiential aspect that can be regarded as designed,

controlled and marketed to further enhance or reinforce the

symbolic values that consumers associate with the SME

winery brand.

Implications for practice

From a managerial viewpoint, the findings highlight the

importance of developing the symbolic values associated with

the brand. Previous literature suggests that the symbolic/

emotional values of the brand are more sustainable as a form

of differentiation and harder for competitors to replicate (de

Chernatony et al., 2000). Therefore it is essential that

managers and operators of SME wineries understand what

values they want the brand to deliver to consumers and ensure

the brand consistently represents these values. The symbolic

values may identify with feelings of prestige, exclusivity,

fashionability, laid-back enjoyment, sophistication, tradition

or countless others. However, care must be taken to ensure

that both the functional values and the symbolic values convey

a similar concept for the consumer. For example, a brand

associated with an symbolic value of laid-back enjoyment

must have a functional value that conveys a similar concept,

such as being easy drinking.

The research also provides the owners, operators and

managers of SME wineries with a better understanding of the

operational and marketing processes that can contribute to

the development of their brand. Rather than interpreting the

brand as the name of the winery or the label on the bottle, it is

essential that managers adopt a holistic approach to the

management of their brand and ensure all business processes

consistently convey the values desired for the winerys brand.

Implications for branding theory

From a theoretical viewpoint, the presented SME winery

branding framework reinforces the conceptualisation of the

brand in terms of functional and symbolic values, as used by

Bhat and Reddy (1998), de Chernatony et al. (2000) and

Meenaghan (1995). Identifying these concepts in brands in

the wine industry, particularly in the brands of SME wineries

with little or no resources devoted to brand development,

highlights the applicability of investigating brands in terms of

their functional and symbolic values.

The findings of this study also provide a general

endorsement of Bhat and Reddys (1998) notion that brands

can simultaneously have both functional and symbolic appeal.

Both of the emergent approaches to branding resulted in

functional and symbolic values simultaneously being inherent

in the SME winery brand. In addition, the findings support

Bhat and Reddys (1998) assertion that brands do not have to

be positioned as prestige to tap into the symbolic needs of the

consumer. Supporting this assertion is the case study evidence

that revealed symbolic values associated with laid-back

enjoyment as well as those of prestige and exclusivity.

More radically, the study suggests an interdependency

between the functional and symbolic properties of branding, a

relationship that does not seem to have been previously

addressed in branding research. For the product-driven

branding wineries, the functional qualities of product quality

were leveraged to develop the symbolic and emotional values

of prestige and exclusivity. In contrast, the marketing-driven

branding wineries placed more emphasis on the end-point of

emotional value and used the cellar door experience,

promotions and extended product range to build the

symbolic properties of the brand image.

Further research

The exploratory nature of the study prompted the adoption of

a qualitative approach, which in turn provided a richness and

depth of understanding of branding from the perspective of

the SME winery. However, the findings and the emergent

model should be seen as a tentative theory that requires

further investigation. Further qualitative research that

investigates a greater number of cases may provide further

refinement and clarification of the model. Additionally, to be

able to test and generalise the findings further to a wider

population, future quantitative research that incorporates a

large-scale survey of randomly selected wineries is required.

The scope of the research was confined to SME wineries in

just two of Australias wine districts, both of which are not

traditionally considered to be grape growing or wine

producing areas. Therefore, further research is

recommended that incorporates different regions to

establish the branding similarities and differences between

SME wineries in different regions of Australia.

Implications for wine marketing theory

The case findings go some way in addressing the current

deficit in the literature regarding the branding of SME

wineries. In doing so, this study presents a two-type typology

for differentiating the strategies that SME wineries adopt for

their operations, marketing and branding. As discussed

previously, one strategy, termed product-driven branding,

is characterised with a dominant focus on the wine produced

with a dominant functional aspect to the brand, the other

approach, termed marketing-driven branding, is

characterised with a greater focus on integrating an

experience with the wine and a greater symbolic aspect to

the brand. As both strategies were identified as being capable

of guiding a SME winery to an effective branding strategy, the

225

A functional and symbolic perspective to branding

Journal of Product & Brand Management

James Mowle and Bill Merrilees

Volume 14 Number 4 2005 220 227

Downloaded by UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN QUEENSLAND At 06:44 03 January 2015 (PT)

Conclusion

Getz, D. (2000), Explore Wine Tourism: Management,

Development and Destinations, Cognizant Communication

Corporation, New York, NY.

Hall, M., Sharples, L., Cambourne, B. and Macionis, N.

(Eds) (2000), Wine Tourism around the World: Development,

Management and Markets, Butterworth-Heinemann,

Oxford.

Keller, K. (2003), Strategic Brand Management: Building,

Measuring and Managing Brand Equity, 2nd ed., PrenticeHall, Upper Saddle River, NJ, p. Hall.

Lockshin, L. (1997), Branding and brand management in

the wine industry, Australian and New Zealand Wine

Industry Journal, Vol. 12 No. 4, pp. 386-7.

Lockshin, L., Rasmussen, M. and Cleary, F. (2000), The

nature and roles of the wine brand, Australian and New

Zealand Wine Industry Journal, Vol. 15 No. 4, pp. 17-24.

Meenaghan, T. (1995), The role of advertising in brand

image development, Journal of Product & Brand

Management, Vol. 4 No. 4, pp. 23-34.

Miles, M.B. and Huberman, A.M. (1994), Qualitative Data

Analysis An Expanded Sourcebook, 2nd ed., Sage, Newbury

Park, CA.

ONeill, M., Palmer, A. and Charters, S. (2002), Wine

production as a service experience the effects of service

quality on wine sales, Journal of Services Marketing, Vol. 16

No. 4, pp. 342-62.

Park, C.W., Jaworski, B.J. and MacInnis, D.J. (1986),

Strategic brand concept image management, Journal of

Marketing, Vol. 50, pp. 135-45.

Parkhe, A. (1993), Messy research, methodological

predispositions and theory development in international

joint ventures, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 18

No. 2, pp. 227-68.

Reid, M. (2002), Building strong brands through the

management of integrated marketing communications,

International Journal of Wine Marketing, Vol. 14 No. 3,

pp. 37-52.

Shelton, T.H. (2001), Product differentiation, in Moulton,

K. and Lapsley, J. (Eds), Successful Wine Marketing, Aspen

Publishers, Gaithersburg, MD, pp. 99-105.

Travis, D. (2000), Emotional Branding: How Successful Brands

Gain the Irrational Edge, Prima Publishing, Roseville, CA.

van Zanten, R. and Bruwer, J. (2002), Integrated marketing

communications: what it really means for the winery,

Australian and New Zealand Wine Industry Journal, Vol. 17

No. 1, pp. 90-4.

Voss, C., Tsikriktsis, N. and Frohlich, M. (2002), Case

research in operations management, International Journal

of Operations & Production Management, Vol. 22 No. 2,

pp. 195-219.

Winemakers Federation of Australia (WFA) (2002), Wine

Tourism Strategic Business Plan 2002-2005: Embrace the

Challenge, Winemakers Federation of Australia, Adelaide.

Yin, R.K. (2003), Case Study Research Design and Methods,

3rd ed., Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA.

The increasingly competitive nature of the Australian wine

industry has resulted in the need for wineries to place a

greater emphasis on the development of a strong brand

identity that will differentiate them from the plethora of other

wineries in the market (van Zanten and Bruwer, 2002).

Despite this, empirical investigation into branding in the wine

industry has been minimal, particularly regarding SME

wineries. The current study adopted a theory building

approach to the research situation in order to further

understand branding from the perspective of the SME

winery. Anchored in the qualitative domain, a multiple case

study methodology was used to investigate the branding of

eight SME wineries in two regions of Australia. Data analysis

resulted in the development of a model depicting a two-type

typology of SME winery branding. Also emerging from

analysis of the case data was the identification of functional

and symbolic values inherent in the SME winery brand. In

addition to providing a better understanding of branding from

the perspective of the SME winery, these findings have also

set a foundation for further research concerning SME winery

branding.

References

ACIL (2002), Pathways to Profitability for Small and Medium

Wineries, ACIL Consulting, Canberra.

Ali-Knight, J. and Charters, S. (1999), Education in a west

Australian wine tourism context, International Journal of

Wine Marketing, Vol. 11 No. 1, pp. 7-18.

Belen del Rio, A., Vazquez, R. and Iglesias, V. (2001), The

role of the brand name in obtaining differential

advantages, Journal of Product & Brand Management,

Vol. 10 No. 7, pp. 452-65.

Beverland, M. (2000), Crunch time for small wineries

without market focus?, International Journal of Wine

Marketing, Vol. 12 No. 3, pp. 16-30.

Bhat, S. and Reddy, S.K. (1998), Symbolic and functional

positioning of brands, Journal of Consumer Marketing,

Vol. 15 No. 1, pp. 32-43.

Bonoma, T.V. (1985), Case research in marketing:

opportunities, problems and a process, Journal of

Marketing Research, Vol. 22, pp. 199-208.

de Chernatony, L. (2001), From Brand Vision to Brand

Evaluation: Strategically Building and Sustaining Brands,

Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford.

de Chernatony, L., Harris, F. and DallOlmo Riley, F. (2000),

Added value: its nature, roles and sustainability, European

Journal of Marketing, Vol. 34 Nos 1/2, pp. 39-56.

Dowling, R. and Getz, D. (2001), Wine tourism futures, in

Faulkner, B., Moscardo, G. and Laws, E. (Eds), Tourism in

the 21st Century: Lessons from Experience, Continuum,

London, pp. 49-66.

Eisenhardt, K. (1989), Building theories from case study

research, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 14 No. 4,

pp. 532-50.

Evans, S. (2002), A cellars market for family wineries,

Australian Financial Review, 24 July.

Fawcett, J. and Downs, F.S. (1992), Conceptual models,

theories, and research, in Fawcett, J. (Ed.), The

Relationship of Theory and Research, 2nd ed., F.A. Davis,

Philadelphia, PA, pp. 101-15.

Executive summary

This executive summary has been provided to allow managers and

executives a rapid appreciation of the content of this article. Those

with a particular interest in the topic covered may then read the

article in toto to take advantage of the more comprehensive

226

Downloaded by UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN QUEENSLAND At 06:44 03 January 2015 (PT)

A functional and symbolic perspective to branding

Journal of Product & Brand Management

James Mowle and Bill Merrilees

Volume 14 Number 4 2005 220 227

description of the research undertaken and its results to get the full

benefit of the material present.

choice focuses on exclusivity and the benefits of search and

discovery. Far from the consumer being able to pick up the

brand at his/her convenience on the supermarket shelf, these

businessmen conclude that their product is so special, so

exclusive that the consumer has to seek it out.

To deliver on this branding strategy we have to feel very

confident in our product. But there is a little secret here the

fact of searching out, of discovering for ourselves, will make

the product taste better. This psychology (we might call it the

product snob approach) says that having slogged all the way

to some dusty town following rather tatty, home-made signs,

we will find that special product. And, having bought some we

will (within reason) believe it to be superior to the product we

buy every week down at Safeways. The search creates the

exclusive brand. When we serve the wine at our dinner party,

we know that our guests cannot go out and buy the wine.

They too have to set out on that search.

Exclusivity vs attraction the case of wine!

It seems right to begin some thoughts about the marketing of

wine by talking about beer especially when we are talking

about the small and medium-sized producers. The Black

Sheep Brewery at Masham in North Yorkshire is a small

brewery making a high quality product drawing on the best

traditions of Yorkshire ale. But Black Sheep is also a

successful visitor attraction set in a fine market town within

the glorious Yorkshire dales. The beer and its manufacture sit

at the heart of this attraction but the marketing extends

beyond the wonders of real ale to encompass the wider

branding of Yorkshire and the Yorkshire Dales.

Mowle and Merrilees notice that there is a difference

between those wineries that focus on the product itself (and

that products quality and presentation) and those wineries

that want to consider the wider opportunities that Black

Sheep Brewery has embraced. This is not to make judgment

on the rejection of a winery as a mere tourist attraction (we

can note that other great Yorkshire beers such as Timothy

Taylors and Worth Brewery have not adopted the Black

Sheep approach) but to recognize that there exists a choice in

branding. But, whatever choice we make, it needs

consideration and examination before we start.

Hiding away a limited business model

The problem with this branding approach lies in the

limitations it places on the business model. We have to be

satisfied with the exclusivity we have but this represents a

limited market. And, sadly, we have to make a living. As a

business we have to grow and develop if we are to survive.

Stasis is not an especially valuable approach to marketing or

management todays cosy exclusivity may become

tomorrows lost opportunity.

Exclusivity and limitations on distribution have long been a

recognized approach to marketing. But the luxury brand

strategy for all the focus on quality and authenticity requires

continuing innovation and change. We cannot allow our

brand to stay still the come and find us strategy needs

renewal and a reason for yesterdays customer to become

tomorrows buyer. If the focus is on the product as the brand

then we have to pay far more attention to product

development. Are these Australian wineries developing

Australian brandy and Australian grappa?

I have concentrated on the rejection of the Black Sheep

brewery approach because it represents a more difficult and

challenging marketing choice. This does not make the choice

of bringing wider associations into the brand a simple choice.

It was easy for Black Sheep the brewery has the image of

Yorkshire and The Dales to draw on. Other places for the

quality of the products they make do not have this

advantage.

Mowle and Merrilees in looking at the marketing of wine

and at smaller wine producers helps us to appreciate better

the difficult challenge facing quality food and drink

producers. The handbook prescribes an approach that will

always tend to dumb down the product message, to aim at

the lowest common denominator. Yet, luxury goods

manufacturers with their exclusive branding represent a

seemingly unattainable target. What we see here is a glimpse

of how we get to this point through focusing on the quality

and exclusivity of the product.

Product or product plus a branding choice

For producers of products such as wine (or beer, cheese,

whisky and brandy) the branding choice described by Mowle

and Merrilees is very important do you focus on the

product itself or try to adopt a wider concept of the brand that

draws on the terrain, ambience and history surrounding the

product? Traditional brand theory suggests that the latter,

product plus approach is likely to prove more fruitful we

have gathered a broader range of associations rather than

concentrating on the specific features of the product itself.

Mowle and Merrilees suggest that, in looking at Australian

wineries, some have thought seriously about the choice. And,

the result of this thought is to reject the jolly tourist

positioning in favour of difficulty, exclusivity and the value of

the product itself.

As marketers we should try to appreciate the importance of

this decision-making process. If (and I am sure this has been

done) some clever marketing consultant is dragged in to

advise, the result will be to opting for the exciting, outward

looking and dynamic product plus. Brand marketing theory

says that a product needs intangible associations things that

add colour to the product. On its own the product is not

enough. But perhaps, when we are looking at really high

quality products, targeted at mid- and upper-scale customers

and playing to the idea of exclusivity and luxury . . . perhaps

we do not need that extra justification for the brand?

Go on then, I challenge you . . . find me?!

Mowle and Merrilees report on the branding choice of several

Australian wineries. The authors note that some of these have

made a clear branding choice one not made out of

arrogance or ignorance but specifically and consciously. This

(A precis of the article A functional and symbolic perspective to

branding Australian SME wineries. Supplied by Marketing

Consultants for Emerald.)

227

Downloaded by UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN QUEENSLAND At 06:44 03 January 2015 (PT)

This article has been cited by:

1. Prof. T.C. Melewar and Prof. Bill Merrilees, Mari Juntunen. 2014. Interpretative narrative process research approach to corporate

renaming. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal 17:2, 112-127. [Abstract] [Full Text] [PDF]

2. Michel Rod, Tim Beal. 2014. The experience of New Zealand in the evolving wine markets of Japan and Singapore. Asia-Pacific

Journal of Business Administration 6:1, 49-63. [Abstract] [Full Text] [PDF]

3. Emmanuel Selase Asamoah. 2014. Customer based brand equity (CBBE) and the competitive performance of SMEs in Ghana.

Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 21:1, 117-131. [Abstract] [Full Text] [PDF]

4. Richard Mitchell, Karise Hutchinson, Barry Quinn. 2013. Brand management in small and medium-sized (SME) retailers: A

future research agenda. Journal of Marketing Management 29:11-12, 1367-1393. [CrossRef]

5. Jenny Sandbacka, Satu Ntti, Jaana Thtinen. 2013. Branding activities of a micro industrial services company. Journal of Services

Marketing 27:2, 166-177. [Abstract] [Full Text] [PDF]

6. Sang-Woo Seo. 2012. Qualitative Research for Investigating the Attributes and Internal Structure of Fashion Brand Authenticity.

The Korean Society of Costume 62:4, 181-194. [CrossRef]

7. Professor Jesus CamraFierro, Dr Edgar Centeno, Mari Juntunen. 2012. Cocreating corporate brands in startups. Marketing

Intelligence & Planning 30:2, 230-249. [Abstract] [Full Text] [PDF]

8. Jing Hu, Xin Liu, Sijun Wang, Zhilin Yang. 2012. The role of brand image congruity in Chinese consumers' brand preference.

Journal of Product & Brand Management 21:1, 26-34. [Abstract] [Full Text] [PDF]

9. Richard Mitchell, Karise Hutchinson, Susan Bishop. 2012. Interpretation of the retail brand: an SME perspective. International

Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 40:2, 157-175. [Abstract] [Full Text] [PDF]

10. Melodena Stephens Balakrishnan. 2011. Protecting from brand burn during times of crisis. Management Research Review 34:12,

1309-1334. [Abstract] [Full Text] [PDF]

11. Gillian Horan, Michele O'Dwyer, Siobhan Tiernan. 2011. Exploring management perspectives of branding in service SMEs.

Journal of Services Marketing 25:2, 114-121. [Abstract] [Full Text] [PDF]

12. Melodena Stephens Balakrishnan, Ramzi Nekhili, Clifford Lewis. 2011. Destination brand components. International Journal of

Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research 5:1, 4-25. [Abstract] [Full Text] [PDF]

13. Clin Guru, Franck Duquesnois. 2011. The Website as an Integrated Marketing Tool: An Exploratory Study of French Wine

Producers. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship 24:1, 17-28. [CrossRef]

14. Demetris Vrontis, Alkis Thrassou, Michael R Czinkota. 2011. Wine marketing: A framework for consumer-centred planning.

Journal of Brand Management 18:4-5, 245-263. [CrossRef]

15. Alessandra Zamparini, Francesco Lurati, Laura G. Illia. 2010. Auditing the identity of regional wine brands: the case of Swiss

Merlot Ticino. International Journal of Wine Business Research 22:4, 386-405. [Abstract] [Full Text] [PDF]

16. Mari Juntunen, Saila Saraniemi, Milla Halttu, Jaana Thtinen. 2010. Corporate brand building in different stages of small

business growth. Journal of Brand Management 18:2, 115-133. [CrossRef]

17. Sabrina Bresciani, Martin J. Eppler. 2010. Brand new ventures? Insights on startups' branding practices. Journal of Product &

Brand Management 19:5, 356-366. [Abstract] [Full Text] [PDF]

18. Martine Spence, Leila Hamzaoui Essoussi. 2010. SME brand building and management: an exploratory study. European Journal

of Marketing 44:7/8, 1037-1054. [Abstract] [Full Text] [PDF]

19. Melodena Stephens Balakrishnan. 2009. Strategic branding of destinations: a framework. European Journal of Marketing 43:5/6,

611-629. [Abstract] [Full Text] [PDF]

20. Karen Miller, Doren Chadee. 2008. The relevance and irrelevance of the brand for small and medium wine enterprises. Small

Enterprise Research 16:2, 32-44. [CrossRef]

21. Demetris Vrontis, Stanley J Paliwoda. 2008. Branding and the Cyprus wine industry. Journal of Brand Management 16:3, 145-159.

[CrossRef]

22. Jukka Ojasalo, Satu Ntti, Rami Olkkonen. 2008. Brand building in software SMEs: an empirical study. Journal of Product &

Brand Management 17:2, 92-107. [Abstract] [Full Text] [PDF]

23. Johan Bruwer, Calin Gurau, Franck Duquesnois. 2008. Direct marketing channels in the French wine industry. International

Journal of Wine Business Research 20:1, 38-52. [Abstract] [Full Text] [PDF]

24. Temi Abimbola, Christine Vallaster, Bill Merrilees. 2007. A theory of brandled SME new venture development. Qualitative

Market Research: An International Journal 10:4, 403-415. [Abstract] [Full Text] [PDF]

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Interior Spaces and The Layers of Meaning: Volume 5, Issue 6Documento17 pagineInterior Spaces and The Layers of Meaning: Volume 5, Issue 6Arlan BalbutinNessuna valutazione finora

- Sbi Clerk 2019: Memory Based PaperDocumento12 pagineSbi Clerk 2019: Memory Based Paperpeter jukerbergNessuna valutazione finora

- In Teaching Araling Panlipunan: Constructivism Cognitivism ExperiantialismDocumento2 pagineIn Teaching Araling Panlipunan: Constructivism Cognitivism ExperiantialismBONILITA CORDITANessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 4 - Creativity in AdvertisingDocumento30 pagineUnit 4 - Creativity in AdvertisingEmmanuel EdiauNessuna valutazione finora

- Salesforce Data Architect Certification GuideDocumento254 pagineSalesforce Data Architect Certification Guideglm.mendesrNessuna valutazione finora

- William R. Uttal - The New Phrenology - The Limits of Localizing Cognitive Processes in The Brain (2001, The MIT Press)Documento139 pagineWilliam R. Uttal - The New Phrenology - The Limits of Localizing Cognitive Processes in The Brain (2001, The MIT Press)gfrtbvhNessuna valutazione finora

- Action Research and LewinDocumento23 pagineAction Research and LewinAna InésNessuna valutazione finora

- Making Mathematical ConnectionsDocumento2 pagineMaking Mathematical Connectionschoo3shijunNessuna valutazione finora

- Bhargav Kannan's Element Synthesis Model RubricDocumento2 pagineBhargav Kannan's Element Synthesis Model RubricShruthiNessuna valutazione finora

- Santiago Sierra - Interviews - WEBDocumento264 pagineSantiago Sierra - Interviews - WEBSantiago Sierra100% (1)

- Property Rights Philosophic FoundationsDocumento156 pagineProperty Rights Philosophic FoundationsAndré Luis Lindquist Figueredo100% (1)

- Vermaas Et Al (2011)Documento134 pagineVermaas Et Al (2011)Julio CésarNessuna valutazione finora

- Sains - Tahun 5Documento60 pagineSains - Tahun 5Sekolah Portal100% (9)

- Canguilhem, Georges - The Death of Man or The Exhaustion of The CogitoDocumento11 pagineCanguilhem, Georges - The Death of Man or The Exhaustion of The CogitoLuê S. PradoNessuna valutazione finora

- курсова 1Documento33 pagineкурсова 1Sophiya HorobiovskaNessuna valutazione finora

- Daily Lesson Log: Grade 12Documento34 pagineDaily Lesson Log: Grade 12Maren PendonNessuna valutazione finora

- Customer Experience ManagementDocumento11 pagineCustomer Experience ManagementRichard TineoNessuna valutazione finora

- Enacting The World Seeking Clarity On en PDFDocumento20 pagineEnacting The World Seeking Clarity On en PDFremistofelesNessuna valutazione finora

- Electrical Installation and Maintenance NC II CGDocumento23 pagineElectrical Installation and Maintenance NC II CGRusshel Jon Llamas Macalisang83% (12)

- Intro To MathDocumento22 pagineIntro To MathMonwei YungNessuna valutazione finora

- Barry Buzan (2004) - From International To World SocietyDocumento12 pagineBarry Buzan (2004) - From International To World SocietyCarl Baruch PNessuna valutazione finora

- Modular Introduction To The Philosophy of The Human Person - Module 1 - Q1Documento25 pagineModular Introduction To The Philosophy of The Human Person - Module 1 - Q1Harlyn Cantor CarreraNessuna valutazione finora

- 2.managing Change, Creativity and Innovation-P.81-94Documento14 pagine2.managing Change, Creativity and Innovation-P.81-94Hạnh BùiNessuna valutazione finora

- Article Elc 612 Learning CognitionDocumento5 pagineArticle Elc 612 Learning CognitionDonald HallNessuna valutazione finora

- Wolff-Michael Roth, Luis Radford A Cultural-Historical Perspective On Mathematics Teaching and LearningDocumento195 pagineWolff-Michael Roth, Luis Radford A Cultural-Historical Perspective On Mathematics Teaching and Learningtomil.hoNessuna valutazione finora

- Soc401. Race Class and Identity Group Assignment.-1Documento8 pagineSoc401. Race Class and Identity Group Assignment.-1Innocent T SumburetaNessuna valutazione finora

- Language Use in Ola Rotimi'S The Gods Are Not: To Blame: A Psychological PerspectiveDocumento14 pagineLanguage Use in Ola Rotimi'S The Gods Are Not: To Blame: A Psychological Perspectivebibatadembele569Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ministry of Health and Social WelfareDocumento21 pagineMinistry of Health and Social WelfareNicole TaylorNessuna valutazione finora

- Mona Baker - Contextualization in TransDocumento17 pagineMona Baker - Contextualization in Transcristiana90Nessuna valutazione finora

- (H.J. Paton) The Categorical Imperative - A Study in Kant's Moral PhilosophyDocumento284 pagine(H.J. Paton) The Categorical Imperative - A Study in Kant's Moral PhilosophySebastian Santos Sampieri Le-RouxNessuna valutazione finora