Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Helping The Poor

Caricato da

Cid Benedict PabalanTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Helping The Poor

Caricato da

Cid Benedict PabalanCopyright:

Formati disponibili

1

Introduction

On November 8, 2013, typhoon Yolanda hit the eastern seaboard of the Philippines

and quickly barreled across its central islands. Even though the authorities evacuated about

800,000 people ahead of the typhoon, the death toll was high. The casualties from the super

typhoon draws close to 6,000, the countrys disaster bureau reported on December 12, 2013.

National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC) spokesperson

Major Reynaldo Balido said that 1,779 individuals remained missing but he explained that

only few cadavers were been retrieved more than a month after Yolanda ravaged most of the

cities and towns in Samar and Leyte Provinces.

Upon news of the catastrophe from typhoon Yolanda in the Philippines, more than a

few countries have immediately pledged assistance. According to the Department of Foreign

Affairs (DFA), they have already monitored a total of 23 countries (as of November 11,

2013) along with the United Nations (UN) and the European Union (EU) that have offered

humanitarian assistance and disaster relief to the victims of Yolanda. The offers of assistance

vary from deployment of search-and-rescue teams and medical personnel; provision of relief

goods, such as food, water, tents, and blankets, among others; provision of medical supplies

and vaccine; deployment of ships and aircrafts; and cash donations.

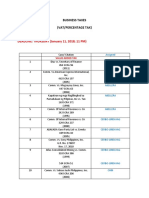

Below is the list of countries that have made offers of assistance:

1. Australia

2. Belgium

3. Canada

4. China

5. Denmark

6. Finland

7. Germany

8. Hungary

9. Indonesia

10. Israel

11. Japan

12. Malaysia

13. The Netherlands

14. New Zealand

15. Norway

16. Russia

17. Singapore

18. Spain

19. Sweden

20. Turkey

21. UAE

22. UK

23. USA

Financial aid

Medics, rapid response team, search and rescue personnel

Financial aid; in-kind donations

Financial aid

Financial aid

In-kind donations

Medics, rapid response team and search and rescue

Medics, rapid response team and search and rescue

In-kind donations

Medics, rapid response team and search and rescue

Medics, rapid response team and search and rescue

Medics, rapid response team and search and rescue, supplies

Financial aid

Financial aid

Financial aid

Medics, rapid response team, search and rescue personnel

Financial aid

In-kind donations

Financial aid

In-kind donations, medics, rapid response and search and rescue

Financial aid

Financial aid

Financial aid, deployment of ships and aircrafts, and medics

The outreach made in the Philippines is just one of the many instances where various

affluent countries have extended their arms to give aid and support for those who are needy.

Generally, people might think that it is a natural consequence for richer nations to give aid to

poorer nations since they have concentrated wealth within their hands. For many, they

consider this altruistic act as the right thing to do. But, there are several questions worth

exploring. For instance, do wealthy people acquire their wealth at the expense of the needy?

How great is the discrepancy between the rich and the poor? How poor are the poor? How

great a burden will fall on the haves if they come to the assistance of the have nots? In

the main, the answers to these question even lead us further to the ultimate issue: Do rich

nations have an obligation to help poor nations?

In an attempt to give answers to the issue, this paper will look into some facts about

poverty and about wealth. It seeks to find the reasons behind why there are some who

support the idea of helping the poor and why there are others who oppose it. Moreover, this

paper aims to correlate the views of two of the most famous theorists regarding the issue

Peter Singer from Practical Ethics and Garret Hardin from Lifeboat Ethics.

Some Facts About Poverty

More than one billion people live in extreme poverty, surviving on less than one

dollar a day. The worlds poor suffer from a lack of adequate shelter, health care, education,

protection from violence, and a voice in what happens in their communities. Every year,

almost 11 million children die from preventable diseases and more than half a million

women die during pregnancy or childbirth. It has been recently estimated that more than 4

billion of the worlds poor are excluded from the rule of law1, resulting in the lack of legal

protection of their rights and entitlements.2

McNamara has summed up absolute poverty as a condition of life so characterized

by malnutrition, illiteracy, disease, squalid surroundings, high infant mortality and low life

expectancy as to be beneath any reasonable definition of human decency. Absolute poverty,

is as McNamara has said, responsible for the loss of countless lives, especially among

infants and young children. When absolute poverty does not cause death, it still causes

misery of a kind not often seen in the affluent nations.

Death and disease apart, absolute poverty remains a miserable condition of life, with

inadequate food, shelter, clothing, sanitation, health services and education. The Worldwatch

Institute estimates that as many as 1.2 billion people or 23 percent of the worlds

population live in absolute poverty. For the purposes of this estimate, absolute poverty is

defined as the lack of sufficient income in cash or kind to meet the most basic biological

needs for food clothing, and shelter. Absolute poverty is probably the principal cause of

human misery today.3

1 The UN rule of law approach is based on international norms and standards,

including the countless UN treaties, declarations, guidelines and bodies of

principles that represent universally applicable standards.

2 Poverty Reduction, United Nations Rule of Law, available at

http://www.unrol.org, last viewed December 13, 2013

3 Practical Ethics, 2nd ed. (Cambridge University Press, 1993)

Some Facts About Wealth

We are all aware of the inequality affecting the distribution of wealth in the world. The fact

that 50% of the adult population accounts for 90% of the wealth in the world comes as no

surprise. The fact that 10% of the population possesses 83% of the wealth is a little more

surprising. But the fact that 43% of the worlds wealth is in the hands of only 1% of the

population is not easy to accept and probably very unfair. These are some of the conclusions

drawn from the report published by the Credit Suisse Research Institute under the title of

Global Wealth Report in October 2010.

Even so, the geographical distribution of wealth is logically concentrated in the areas

with the highest levels of economic development. Europe accounts for 32% of the worlds

wealth. North America accounts for 31% and the Pacific basin (excluding India and China)

accounts for 22%. The remaining 15% is divided between China (8%), Latin America (4%),

India (2%) and Africa (1%), which together account for 50% of the population. In terms of

countries, the top places on the ranking correspond to Switzerland, Norway, Australia,

Singapore and France as the five countries with the highest level of individual wealth, in

excess of $250,000 per adult. On the second level, above $200,000, we have the United

States, Japan, United Kingdom and Canada. The countries with the highest increase in

wealth in the last decade include Russia and Indonesia, where levels have grown fivefold.4

Against the picture of absolute poverty that McNamara has painted, one might pose a picture

of absolute affluence. Those who are absolutely affluent are not necessarily affluent by

comparison with their neighbors, but they are affluent by any reasonable definition of human

needs. This means that they have more income than they need to provide themselves

adequately with all the basic necessities of life. After buying food, shelter, clothing, basic

health services, and education, the absolutely affluent choose their food for the pleasures of

the palate, not to stop hunger; they buy new clothes to look good, not to keep warm; they

move house to be in a better neighborhood or have a playroom for their children, not to keep

out of the rain; and after all this there is still money to spend on stereo systems, video

cameras, and overseas holidays. These, therefore, are the countries and individuals who

have wealth that they could, without threatening their own basic welfare, transfer to the

absolutely poor.

4 Wealth Distribution, Staggering Facts About Global Rich, available at

http://www.businessinsider.com, last viewed December 13, 2013

The Obligation to Assist

In "Famine, Affluence, and Morality", one of Singer's best-known philosophical

essays, he argues that some people living in abundance while others starve is morally

indefensible.5 Singer proposes that anyone able to help the poor should donate part of their

income to aid poverty relief and similar efforts. Singer reasons that, when one is already

living comfortably, a further purchase to increase comfort will lack the same moral

importance as saving another person's life. Singer himself reports that he donates 25 percent

of his salary to Oxfam and UNICEF and he is a member of Giving What We Can, an

international society for the promotion of poverty relief inspired by Singer's arguments. In

"Rich and Poor", the version of the aforementioned article that appears in the second edition

of Practical Ethics, his main argument is presented as follows:

If we can prevent something bad without sacrificing anything of comparable

significance, we ought to do it; absolute poverty is bad; there is some poverty we can

prevent without sacrificing anything of comparable moral significance; therefore we

ought to prevent some absolute poverty.

Singer's most recent book, The Life You Can Save, makes the argument that it is a

clear-cut moral imperative for citizens of developed countries to give more to charitable

causes that help the poor. While Singer acknowledges that there are problems with ensuring

that money goes where it is most needed and that it is used effectively, he does not think that

these practical difficulties undermine his original conclusion (that people should make a

much greater effort to reduce poverty).6

In view of this, helping is not as conventionally thought, a charitable act that it is

praiseworthy to do, but not wrong to omit; it is something that everyone ought to do. To

formally set the argument abovementioned, it would look like this:

First premise:

If we can prevent something bad without sacrificing anything

of comparable significance, we ought to do it.

5 "Famine, Affluence, and Morality, Philosophy and Public Affairs, vol. 1, no. 3

(Spring 1972), pp. 229243.

6 Life You Can Save: How to Live, or How to Give?, Philanthropy Action, 1 April

2009

Second premise: Absolute poverty is bad

Third premise:

There is some absolute poverty we can prevent without

sacrificing anything of comparable moral significance.

Conclusion:

We ought to prevent some absolute poverty.

The first premise is the substantive moral premise on which the argument rests. The

second premise is unlikely to be challenged. Absolute poverty is, as McNamara put it,

beneath any reasonable definition of human decency and it would be hard to find a

plausible ethical view that did not regard as a bad thing. The third premise is more

controversial. It claims only that some absolute poverty can be prevented without the

sacrifice of anything of comparable significance. But the point is not whether a personal

contribution will make any noticeable impression on world poverty as a whole, but whether

it will prevent some poverty. Thus, if without sacrificing anything of comparable moral

significance we can provide with just one family with the means to raise itself out of

absolute poverty, the third premise is vindicated.

Our affluence means that we have income we can dispose of without giving up the

basic necessities of life, and we can use this income to reduce absolute poverty.

The Case Against Helping the Poor

Taking care of our own.

The moral theory known as the ethics of care implies that there is moral

significance in the fundamental elements of relationships and dependencies in human life. 7

Considering this, there is no doubt that we do instinctively prefer to help those who are close

to us. Few could stand by and watch a child drown; many can ignore a famine in Africa. But

the question is not what we usually do, but what we ought to do, and it is difficult to see any

sound moral justification for the view that distance, or community membership makes a

crucial difference to our obligations.

Generally, we feel obligations of kinship more strongly than those of citizenship. After all,

which parents could give away their last bowl of rice if their own children were starving? To

do so would seem unnatural and contrary to our nature as biologically evolved beings. Thus,

7 Care Ethics, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, available at

http://www.iep.utm.edu, last viewed December 13, 2013

we should look after those near us, our families, and then the poor in our own country,

before we think about poverty in distant places.

Population and the Ethics of Triage

Perhaps the most serious objection to the argument that we have an obligation to

assist is that since the major cause of absolute poverty is overpopulation, helping those now

in poverty will only ensure that yet more people are born to live in poverty in the future.

Thus, this objection is taken to show that we should adopt a policy of triage. The

term comes from medical policies adopted in wartime. With too few doctors to cope with all

the casualties, the wounded were divided into three categories: those who would probably

survive without medical assistance, but otherwise would not, and those who even with

medical assistance probably would not survive. Only those in the middle category were

given medical assistance. The concept was to use limited medical resources as effectively as

possible. For those in the first category, medical treatment was not strictly necessary; for

those in the third category, it was likely to be useless.

It has been suggested that we should apply the same policies to countries, according

to their prospects of becoming self-sustaining. We should not aid countries that even without

our help will soon help to feed their populations. We would not aid countries that, even with

our help, will not be able to limit their population to a level they can feed. We should aid

only those countries where our help might make a difference.

Lifeboat Ethics

Lifeboat ethics is a metaphor for resource distribution proposed by the ecologist

Garrett Hardin in 1974. Hardin's metaphor describes a lifeboat bearing 50 people, with room

for ten more. The lifeboat is in an ocean surrounded by a hundred swimmers. The "ethics" of

the situation stem from the dilemma of whether swimmers should be taken aboard the

lifeboat. Hardin compares the lifeboat metaphor to the Spaceship Earth model of resource

distribution, which he criticizes by asserting that a spaceship would be directed by a single

leader a captain which the Earth lacks. Hardin asserts that the spaceship model leads

to the tragedy of the commons. In contrast, the lifeboat metaphor presents individual

lifeboats as rich nations and the swimmers as poor nations.8

To further elaborate, Hardin argues that rich nations are like the occupants of a crowded

lifeboat adrift in a sea full of drowning people. If they try to save the drowning by bringing

them aboard, their boat will be overloaded and they shall all drown. Since it is better that

some survive than none, they should leave others to drown. In the world today, according to

Hardin, lifeboat ethics apply. Thus, the rich should leave the poor to starve, for otherwise

the poor will drag the rich down with them.

Correlation

In the main, the wealth of our planet is unevenly distributed. There are several

factors that have an impact on the life prospects of an individual such that some countries

benefit from the foresight of their politician, while others suffer from revolution or political

corruption. This is where the question comes in whether these matters affect a rich nations

responsibility to a poor one.

Singer argues that the need in poor countries is indeed great and that wealthy nations

have the ability to help. By cutting back on luxuries, he says, the well-to-do can prevent

people from starving to death. Moreover, because great good can be accomplished at a

relatively low cost, wealthy nations have an obligation to do so. Hardin, on the other hand,

does not believe that the cost is really so low. He argues that good can be done, suffering can

be relieved, and lives can be saved, but he warns that the populations of poor countries will

rise at faster rates than will the populations of rich countries. As a result, in the end, the

suffering is just postponed, and more lives will be devastated.

Singers view is indeed remarkable but Hardin equally has a strong point.

Nevertheless, if Hardin is right that poor countries have population problems, then these are

the problems that rich nations should address. Singers concept of aid would include

contraceptive devices, information, and programs, in addition to food and medicine.

However, there is always the possibility that a given nation will be opposed to contraception

or population control and that its population grow unchecked. In such a case, Hardin would

be on a stronger ground. The sovereignty of nations comes into play here.

8 "Lifeboat Ethics: the Case Against Helping the Poor," Psychology Today pp. 38

43.

Millennium Development Goals and Poverty Reduction

World leaders have recognized that the rule of law is crucial for sustained economic

growth, sustainable development and the eradication of poverty and hunger. The United

Nations development agenda, articulated in the eight Millennium Development Goals

(MDGs), based on the Millennium Declaration, calls for the eradication of extreme poverty

in all its dimensions- income poverty, hunger, disease, lack of adequate shelter, gender

inequality, poor education, and environmental degradation. The MDGs include

commitments made by developed nations, such as increased official development assistance

and improved market access for exports from developing countries. The Goals target cutting

global poverty in half by 2015.

Recent international initiatives to highlight the legal empowerment of the poor have

drawn renewed worldwide attention to the linkages among poverty, legal exclusion and

injustice. In many developing countries, laws, institutions, and policies governing economic

and social interactions do not afford equal opportunity and protection to a large segment of

the population, who are mostly poor, minorities, women, children and other disadvantaged

groups. In some cases, laws and institutions impose barriers and biases against the poor and

marginalized groups. Where laws exist protecting and upholding the rights of the poor and

marginalized, institutions and processes can be too difficult and costly for them to access.

The prevalence of corruption and abuse of power in many justice systems most greatly

affects those who are poor and most vulnerable. In many developing countries, informal

justice mechanisms, norms, and practices govern the everyday life of the poor.

UN rule of law activities seek to address the legal exclusion of the poor and

marginalized, ensuring legal protection of and justice for all. This involves a bottom-up

approach of legal empowerment to enable the poor and disadvantaged groups to understand

and claim their entitlements and rights, and access justice, security and services for this

purpose. Support for gender equality, and the inclusion of marginalized groups and groups

subject to discrimination is a key aspect of this work.

The UN rule of law approach is based on international norms and standards,

including the countless UN treaties, declarations, guidelines and bodies of principles that

represent universally applicable standards. It involves support for the realization of

economic, social and cultural rights, as well as civil and political rights. Legislative reform,

institution-building and support for legal assistance and access to justice focus on birth

registration and legal identity, labor, employment and business, housing rights, property and

10

land governance, reproductive health, and environmental protection. Many of these activities

are targeted towards reaching specific MDGs, and creating an overall enabling environment

in countries for social and economic progress.9

In fact, the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) are the most successful Global

Anti-Poverty push in history. The first goal therein is to eradicate extreme poverty and

hunger. Apparently, the target was met five years ahead of the 2015 deadline. The global

poverty rate at $1.25 a day fell in 2010 to less than half the 1990 rate. 700 million fewer

people lived in conditions of extreme poverty in 2010 than in 1990. Moreover, the hunger

reduction target, which is to halve, between 1990 and 2015, the proportion of people who

suffer from hunger, is within reach by 2015.

However, at the global level 1.2 billion people are still living in extreme poverty.

About 870 million people are estimated to be undernourished and more than 100 million

children under age five are still undernourished and underweight. Seeing that the target is

within reach by 2015, nevertheless, the United Nations are encouraging us to step up

because ultimately we can end poverty.

To conclude, we would like to quote the famous words of Nelson Mandela:

In this new century, many of the worlds poorest countries remain

imprisoned, enslaved and in chains. They are trapped in the prison of poverty. It is

time to set them free. Like slavery and apartheid, poverty is not natural. It is manmade and it can be overcome and eradicated by the actions of human beings.

9 Poverty Reduction, United Nations Rule of Law, available at

http://www.unrol.org, last viewed December 13, 2013

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- Social Work Practice With FamiliesDocumento456 pagineSocial Work Practice With FamiliesAlicia Fishlock100% (1)

- Davao City Chapter: Integrated Bar of The Philippines Revised Schedule of Minimum Attorney'S FeesDocumento3 pagineDavao City Chapter: Integrated Bar of The Philippines Revised Schedule of Minimum Attorney'S FeesCid Benedict Pabalan100% (2)

- Davao City Chapter: Integrated Bar of The Philippines Revised Schedule of Minimum Attorney'S FeesDocumento3 pagineDavao City Chapter: Integrated Bar of The Philippines Revised Schedule of Minimum Attorney'S FeesCid Benedict Pabalan100% (2)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Unit 3 SHC 33Documento6 pagineUnit 3 SHC 33grace100% (1)

- Special Education For Children With Disabilities in Malaysia - Progress & ObstaclesDocumento10 pagineSpecial Education For Children With Disabilities in Malaysia - Progress & ObstaclesVivian GraceNessuna valutazione finora

- Batelaan & Gundare 2000 Intercultural EducationDocumento4 pagineBatelaan & Gundare 2000 Intercultural EducationHasanah Faisal HassanNessuna valutazione finora

- Tarrifs and Customs CodeDocumento75 pagineTarrifs and Customs CodeCid Benedict PabalanNessuna valutazione finora

- What Do You Want To Do With Your Booking?: Hi Guest!Documento5 pagineWhat Do You Want To Do With Your Booking?: Hi Guest!Cid Benedict PabalanNessuna valutazione finora

- CE 4 2ndDocumento2 pagineCE 4 2ndCid Benedict PabalanNessuna valutazione finora

- Other FormsDocumento13 pagineOther FormsCid Benedict PabalanNessuna valutazione finora

- Nego CasesDocumento44 pagineNego CasesCid Benedict PabalanNessuna valutazione finora

- By Cid Benedict D. Pabalan: Torts First Exam Hot Tips From Atty. PanchoDocumento1 paginaBy Cid Benedict D. Pabalan: Torts First Exam Hot Tips From Atty. PanchoCid Benedict PabalanNessuna valutazione finora

- Past Exam LaborDocumento2 paginePast Exam LaborCid Benedict PabalanNessuna valutazione finora

- Laperal CaseDocumento7 pagineLaperal CaseYan PascualNessuna valutazione finora

- English Plus PrepositionDocumento8 pagineEnglish Plus PrepositionCid Benedict PabalanNessuna valutazione finora

- LayoutDocumento1 paginaLayoutCid Benedict PabalanNessuna valutazione finora

- Mercantile 2016 PDFDocumento67 pagineMercantile 2016 PDFCyd MatawaranNessuna valutazione finora

- Pre-Week Notes On Labor Law For 2014 Bar ExamsDocumento134 paginePre-Week Notes On Labor Law For 2014 Bar ExamsGinMa Teves100% (7)

- Pabalan Tax 2 Digests Second SetDocumento13 paginePabalan Tax 2 Digests Second SetCid Benedict PabalanNessuna valutazione finora

- Donor's Tax Codal With Ra 10963 AmendmentDocumento3 pagineDonor's Tax Codal With Ra 10963 AmendmentCid Benedict PabalanNessuna valutazione finora

- 5 CorpoDocumento46 pagine5 CorpointerscNessuna valutazione finora

- Exercise: Subject and Verb Agreement ExerciseDocumento4 pagineExercise: Subject and Verb Agreement ExerciseCid Benedict PabalanNessuna valutazione finora

- Exercise: Subject and Verb Agreement ExerciseDocumento4 pagineExercise: Subject and Verb Agreement ExerciseCid Benedict PabalanNessuna valutazione finora

- SEC Express System - Order ConfirmationDocumento2 pagineSEC Express System - Order ConfirmationCid Benedict PabalanNessuna valutazione finora

- Cid Benedict D. Pabalan: Professor: Atty. Louise Marie Brandares - EscobidoDocumento1 paginaCid Benedict D. Pabalan: Professor: Atty. Louise Marie Brandares - EscobidoCid Benedict PabalanNessuna valutazione finora

- Tax AssignmentDocumento6 pagineTax AssignmentCid Benedict PabalanNessuna valutazione finora

- Corpo Sunday Class Outline First ExamDocumento4 pagineCorpo Sunday Class Outline First ExamCid Benedict PabalanNessuna valutazione finora

- Laperal CaseDocumento7 pagineLaperal CaseYan PascualNessuna valutazione finora

- TortsDocumento193 pagineTortsCid Benedict PabalanNessuna valutazione finora

- Municipal Trial Court: Ella Campavilla, of AffectionDocumento4 pagineMunicipal Trial Court: Ella Campavilla, of AffectionCid Benedict PabalanNessuna valutazione finora

- Tax 2 CompiledDocumento106 pagineTax 2 CompiledCid Benedict PabalanNessuna valutazione finora

- Judicial Affidavit Of: Paulo Avelino Paulo AvelinoDocumento4 pagineJudicial Affidavit Of: Paulo Avelino Paulo AvelinoCid Benedict PabalanNessuna valutazione finora

- Judicial Affidavit Of: Ruffa Campavilla-Gutierrez Ruffa Campavilla-GutierrezDocumento5 pagineJudicial Affidavit Of: Ruffa Campavilla-Gutierrez Ruffa Campavilla-GutierrezCid Benedict PabalanNessuna valutazione finora

- Philippine National Police Baganga Municipal Police Station: Physical InjuryDocumento1 paginaPhilippine National Police Baganga Municipal Police Station: Physical InjuryCid Benedict PabalanNessuna valutazione finora

- Inclusiveness: Prepared By: Dinke A. 2021Documento131 pagineInclusiveness: Prepared By: Dinke A. 2021maria tafaNessuna valutazione finora

- Globalization and Social WorkDocumento49 pagineGlobalization and Social Workbebutterfly97100% (1)

- Step by Step Guide For Young EntrepreneursDocumento675 pagineStep by Step Guide For Young EntrepreneursDragomir Eleonora100% (1)

- Voices From The Margin: A Reading of Hira Bansode's Poetry: International Journal of Research (IJR)Documento4 pagineVoices From The Margin: A Reading of Hira Bansode's Poetry: International Journal of Research (IJR)shefali gargNessuna valutazione finora

- Financial Literacy For Developing Countries in AfricaDocumento12 pagineFinancial Literacy For Developing Countries in AfricaJuped JunNessuna valutazione finora

- Inclusive Education: Preparation of Teachers, Challenges in Classroom and Future ProspectsDocumento12 pagineInclusive Education: Preparation of Teachers, Challenges in Classroom and Future ProspectsFaheemNessuna valutazione finora

- Addressing Intolerance and Discrimination Against Muslims: Youth and EducationDocumento60 pagineAddressing Intolerance and Discrimination Against Muslims: Youth and EducationÄbů BäķäŗNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 4 - FINAL Promoting Inclusive CultureDocumento16 pagineChapter 4 - FINAL Promoting Inclusive Cultureelias ferhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Rapp Ginsburg - Enabling DisabilityDocumento24 pagineRapp Ginsburg - Enabling DisabilityTom JousselinNessuna valutazione finora

- NC Drive Teacher Diversity ReportDocumento35 pagineNC Drive Teacher Diversity ReportKeung HuiNessuna valutazione finora

- HISTOPAPER1 - Analysis of "I Hate My Country" by DiamanteDocumento5 pagineHISTOPAPER1 - Analysis of "I Hate My Country" by DiamantereslazaroNessuna valutazione finora

- What Happens To Antiracism When We Are Post-Race?Documento9 pagineWhat Happens To Antiracism When We Are Post-Race?Alana LentinNessuna valutazione finora

- Ashley & Empson (2017) Understanding Social Exclusion in Elite Professional Service Firms - Field Level Dynamics and The Professional Project'Documento19 pagineAshley & Empson (2017) Understanding Social Exclusion in Elite Professional Service Firms - Field Level Dynamics and The Professional Project'Miguel MorillasNessuna valutazione finora

- Fun Fitness FantasyDocumento11 pagineFun Fitness FantasyTania FernándezNessuna valutazione finora

- WB Targeting Assessment of Cash Transfer Program in Gaza and West BankDocumento23 pagineWB Targeting Assessment of Cash Transfer Program in Gaza and West BankJeffrey MarzilliNessuna valutazione finora

- Islamic Voice MagazineDocumento32 pagineIslamic Voice MagazineShakeel AhmadNessuna valutazione finora

- European Roma Rights Center, 2015, Roma Rights PDFDocumento9 pagineEuropean Roma Rights Center, 2015, Roma Rights PDFGabriel Alexandru GociuNessuna valutazione finora

- Social Inclusion ProjectDocumento1 paginaSocial Inclusion ProjectDaniela RotaruNessuna valutazione finora

- Mind The Gap:: Digital England - A Rural PerspectiveDocumento60 pagineMind The Gap:: Digital England - A Rural PerspectiveRanjith KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Employee Engagement Development Inclusion FY17 PDFDocumento19 pagineEmployee Engagement Development Inclusion FY17 PDFAli Alsari AlhashemiNessuna valutazione finora

- Derrick ArmstrongDocumento12 pagineDerrick ArmstrongΒάσω ΤαμπακοπούλουNessuna valutazione finora

- Reporting On Disability: ILO Guidelines For The Media 2016 - Wcms - 127002Documento17 pagineReporting On Disability: ILO Guidelines For The Media 2016 - Wcms - 127002Vaishnavi JayakumarNessuna valutazione finora

- BedDocumento30 pagineBedAnbu AndalNessuna valutazione finora

- The Right To Education For Children With Disabilities From The Earliest AgeDocumento31 pagineThe Right To Education For Children With Disabilities From The Earliest AgeMinadzenoNessuna valutazione finora

- Strategy Ehsaas For Online ConsultationDocumento57 pagineStrategy Ehsaas For Online ConsultationMuhammad AkhtarNessuna valutazione finora

- AlpaharDocumento21 pagineAlpaharGaurav SinghNessuna valutazione finora