Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Research For IB Music EE

Caricato da

May Wai WongTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Research For IB Music EE

Caricato da

May Wai WongCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Bells of Moscow

Background to Prelude in C# Minor

From the Internet (cant remember where)

Composed in 1892

Rachmaninovs most famous prelude

Composed when he was 19

Reminded him of church bells ringing when he was young

From Sergei Rachmaninov: A Lifetime in Music

(p. 49)

And thus one of the worlds most popular piano pieces began is long career, that was

to bring its composer everything-fame and contempt, ease and embarrassment, money

(indirectly) and annoyance aplenty)

One day the Prlude simply came and I put it down. It came with such force that I

could not shake it off even though I tried to do so. It had to be so-so there is was Rachmaninov

This is very much like Schumanns Novelletten

(p. 51)

Op. 3 (Elegy, the Prlude, Melody, Polichnelle and Serenade) were to be dedicated to

his teacher, Arensky

First performed as a group in the Kharkov concert of December 20, 1892.

(p. 53)

Tchaikovsky later wrote to Siloti that is he liked the piano pieces very much,

especially the Prlude and the Melody

(p. 162-163)

I found myself out of pocket. I needed money, and I wrote this Prlude and sold it to

a publisher for what he would give

(p. 175)

Rachmaninovs preludes differ from Chopins in that they generally incline towards

a solid and often polyphonic treatment, a broad structure, or towards clear contrasts of

musically independent sections; in a word, they approach Chopins exceptions to his

own rule, as in the famous D-flat major prelude. Yuli Engel

Instead of Chopins two page or even half page works. Rachmaninovs Prludes

grow into 4 6 or even 8 pages. This is a growth to be welcome when it derives from

th4 natural tendency of a musical idea to revel itself as fully as possible, as for

example, the beautiful Prlude-March in G minor, op. 23.

(p. 253)

He has amusingly confessed that it still pursues him everywhere, Rachmaninov is

that Prelude, just as Charlie Chaplin is a pair of baggy trousers and hypertrophied

boots, and George Robey is a pair of arched eyebrows Ernest Newman

(p. 295-296)

I really don't care anymore. Something about him playing two notes more and being

expected to play it everywhere he goes

(p. 327)

I play it without feeling like a machine Rachmaninov

From Rachmaninov: Life, Works, Recordings

(p.48)

And from its sinister ff opening through the surprising ppp continuation, the agitated

central section, the mournful tolling of its final bars, when the music evaporates, its

remains a genuinely imaginative statement, although the climax can seem too

passionate for so short a piece. Even during this there remains an indefinable sense of

fate hovering and the Prelude in C Sharp minor signaled and important aspect of

Rachmaninovs artistic personality.

(p. 87)

Which proved extremely popular in Britain and elsewhere: so much that London

publishers brought out several editions with titles such as The Burning of Moscow,

The Day of Judgment and, still less plausibly, The Moscow Waltz.

(p. 95)

(On Piano Concerto No.2) Each of the movements begins by changing key, this one

from F minor to the home key of C minor, moving a semitone at a time and ending by

empathetically expressing the works germ motif: (G) A flat F G C. This type of

chord sequence was a recurring preoccupation of Rachmaninovs, surely born out of

improvisation at the keyboard, an earlier instance being the final eight bars of the

Prelude Op. 3 No. 2.

(p. 277)

(Rachmaninov recorded his compositions on the gramophone) The Prelude is most

beautifully phrased, especially its first page.

Influences

So far, none have been listed, but as this is an early composition, influences are most

likely to be drawn from Nationalism composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (The Five)

and Pyotr Tchaikovsky

Characteristics of Romantic music in general

http://www.essential-humanities.net/western-art/music/romantic/

Unrestrained emotional expression

Romantic composers burst free of the limitations imposed by classicism (balance,

harmony, clarity, simplicity), embracing whatever aesthetic techniques proved

effective in capturing a particular feeling. Throughout the Romantic age, composers

increasingly embraced abrupt shifts in dynamics and temp, an experimented with

novel melodies and chord progressions

Mainstream Romantic music came from Germany, Austria, Italy and France, whereas

regional Romantic music, which featured a distinct local flavor flourished during

the late Romantic period

Featured artistic freedom and experimentation

Featured extremities on the chromatic scale new melodic and harmonic

possibilities. Key shifting became much more frequent within manuscripts

A wide range of instrument combination and techniques were pioneered during the

Romantic age, thereby unleashing the full potential of orchestral expression.

The pianos full expressive potential was achieved

(Of the mainstream Romanticists) Full romantics pursued Romanticism

unconditionally, while the conservative Romantics retained a significant of classicism

(structure, clarity, simplicity).

Regional Romanticists infused Western art music with the folk music of their native

lands (Rachmaninov fits in the category)

Features of Russian Nationalist music

http://www.dorak.info/music/national.html

In the 1830s, a national musical style- marked with emphasis on folk songs, folk

dances, and especially folk rhythms began to emerge in Russia. This coincided with

similar nationalistic movements in other countries such as Poland, Bohemia, and

Scandinavian countries.

There was not a distinguished Russian Art Music style before the 1830s. Two

important sources of genuine Russian music as inspiration for the nineteenth century

Russian composers were church music (Russian chants) and folk music.

The Russian Five (Balakirev, Borodin, Cui, Mussorgsky and Rimsky-Korsakov) use

folk material extensively in their music.

Balakirevs symphonic poem Tamara, Borodins Polovtzian Dances from Prince Igor,

and Rimsky-Korsakoffs Scheherazade are examples of Russian orientalism.

Kamarinskaya is free variations on two Russian folk songs written by Glinka in 1848.

In this piece, he surmounted restrictions on folk songs by the additions of counter

melodies to them. The folk tunes (wedding song and dance song) are used as a cantus

firmus against which new melodies and figurations are worked. The songs used by

the composer are extremely repetitive which makes arabesque-like ornaments

inevitable.

In his second string quartet in F, he uses the combination of Russian harmony with a

Norwegian melodic contour (falling leading note) in the Scherzo (Tchaikovsky)

The Russian composers developed a unique idiom which contained the following: the

cell development technique (a short motif or phrase repeated exactly or slightly

varied), pronounced interest in orchestral colour, variety of dynamics, use of

(inverted) pedal points, drone basses, dominant hovering, use of exotic harmony

(chromatic or modal), pentatonic or modal tunes and their associated harmonies, and

additive structures resulting from the cell development on a big scale, small melodic

compass, recurring intervallic shapes) like the falling fourth in Tchaikovskys

Serenade for Strings.

In the nineteenth century, folk elements (repetition of single notes, phrases, dance like

rhythms, real or imitation folk-tunes) were integrated into Russian music. Folk tales

were used as subjects for opera and symphonic poems.

Russian music made an important contribution to the development of harmony by the

use of whole-tone elements, chromanticism and higher discords

The use of whole tones inevitably resulted in a frequent use of augmented triads as all

triads using whole tones are augmented. (Harmonic clich: chord 1 augmented

chord 1 and V1b, has for example, tonal/modal ambiguity)

New rhythmic patterns: quintuple time, five bar phrases and the general disruption of

conventional rhythmic patterns.

Polysyllabic Russian words had an obvious influence on the newly emerged rhythmic

patterns which influenced instrumental music too.

Repetition rather than motivic development produced new attitudes to form. Such

repetition or breakdown of extended phrases into small bricks (or mosaics) replaced

thematic development and created new additive structures (mosaic form)

Constantly changing rhythm, dynamics, volume and orchestral tone colour disguises

repetitiveness and prevent monotony.

The whole tone scale due to inevitable augmented triads and lack of semi tonal pull f

the leading note was a significant factor in the disintegration of tonality.

Russian Nationalist Composers

From The Rough Guide to Classical Music

Mily Balakirev (the leader)

Csar Cui

Modest Mussorgsky: (p. 366) Rimsky-Korsakov, while recognizing that Mussorgsky

was talented, original, full of so much that was new and vital asserted that his

manuscript also revealed absurd, disconnected harmony, ugly par writing,

sometimes strikingly illogical modulationunsuccessful orchestration and began a

dedicated project to make his music more performable, either by completing works

Mussorgsky had failed to finish or by the wholesale rewriting of complete

compositions. Yet these are the very elements-power, earthiness and sheer invention

that gave Mussorgsky his unique musical personality.

(p. 368) [On Boris Godunov] Mussorgsky exploits the dramatic potential of this

scenario to the full, creating a powerful contrast between the spectacle of the

Coronation Scene and Boriss inner torment as he tries and fails to come to terms with

his guilt. Composers as diverse as Debussy and Janacek were undoubtedly influenced

by Mussorgskys sill in word setting, in particular his way of setting dramatic prose

so that the music effects the inflections of the spoken text.

[on Rimsky improving the composition] While Rimskys version is undoubtedly

colourful, it misses the profundity and dark hues of the original orchestration.

(p. 369) [On his songwriting] Mussorgsky is arguably the greatest nineteenth century

songwriter after Schubert and Schumann, though this aspect of this music is not well

enough known outside of Russia.

He also, more than any other composer of the period, had o qualms about introducing

the modality of folk song into his vocal music.

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov: (p. 445) Most of his operas are an exotic blend of

supernatural elements within a Russian folk setting.

Alexander Borodin: (p. 88) Like Tchaikovskys earlier symphonies, Borodins

employ typically Russian harmonies, melodies and rhythms against a fairly

conventional Germanic formal background. Symphony No. 1, in particular, looks

back to Schumann, one of Borodins prime influences at the time, yet is a distinctly

Russian work, particularly in the use of a folk song in the Scherzo and the oriental

lyricism of the slow movement.

The Russian Submediant in the Nineteenth Century

Russian art music grew up under peculiar conditions, partially isolated from

contemporary Western music

Closely linked with a folk-music marked by various tonal peculiarities

Russian musicians have always shown a peculiar intellectual interest in what we may

call the curiosities of harmony and that two or three of them have been revolutionary

innovators.

Russian harmony significantly increases the importance of the submediant function in

a major-mode context, by emphasizing the sixth degree as an adjunct harmonic factor

to the tonic triad, and by promoting the submediant as an alternative tonal focus to the

tonic function, even by merging the relative major and minor into a single superkey

with two tonics

We can see this mannerism, which I call the Russian sixth, first emerging as an

individual phenomenon in Glinka and Dargomizhsky, latfer achieving full flower in

Tchaikovsky and the Five

In the Western diatonic system the relationship of relative major and minor is as basic

and intrinsic as the same key signature that is used for both; at the same time, it goes

much further than mere notation or theoretical construct

Even the notation of key signatures requires that the leading tone of the relative minor

has to be indicated by an additional inflectional sign, and often this is necessary for

the sixth degree as well

The association of relative major and minor as a resource of tonality and form has

been validated by more than three centuries of tonal music even since the late

sixteenth century

[Development since the Baroque era] crowning examples of the German Baroque

chorale, which reveal numerous instances where tonal functions are guided by

various modal characteristics of the older cantus firmi, and may be unexpected; in

many instances, wen the primary tonality is minor, the stronger secondary tonal

function is the relative major

The relative minor and major tonic functions (or, alternatively, the tonic and median)

are strengthened by their preceding dominants. Notwithstanding that relative minor

and major appears within the same phrase, this is unmistakably tonal harmony.

[Classical Era] By the time of the flowering of the classical sonata form in the minor

mode, the same relationship expands to include the assurance of the relative major for

the second key area of the exposition, in nearly all cases.

Two things are primarily significant about this result. First the reverse association

does not occur; in chorales in the major mode, the relative minor is not tonicised

disproportionately to other secondary functions

Modal harmony is a term that is often used but seldom precisely defined. The early

Baroque chorales are often said to exhibit both modal and tonal harmony, and a

modal origin is often offered as an explanation of diatonic deviation from tonal

harmony within common practice.

Musical Features of Romantic Music

http://www.mostlywind.co.uk/romantic.html

The Romantic composers were able to express themselves freely and personally, thus

melodies tend to be much more emotional than that of music from the Classical Era.

Romantic music developed over the course of around a hundred years. Many new

styles of composition were created, such as the lied, which combined Romantic

poetry with voice and piano, waltz, mazurka, polonaise and etude (study piece). Other

forms of music were created, such as piano in free form eg. Fantasy, arabesque,

rhapsody, romanza, ballade, nocturnes and symphonic works eg. The tone poem.

Romanic music contained warm and personal melodies, expressive indications eg.

Dolce, con, amore, con fuoco, implied interpretive freedom (rubato) and charmonic

colour (new chords such as the ninth). Colour was intensified by the improvement of

the instruments eg. Piano, which was more commonly used in Romantic

compositions.

Prominent composers: Beethoven, Liszt etc

Melody: Long, lyrical melodies with irregular phrases; Wide, somewhat angular

skips, extensive use for chromatics; vivid contrasts a variety of melodic ideas within

one movement

Rhythm: Frequent changes in the tempo and time signature

Texture: homophonic

Timbre: a great variety of tone colour; woodwind and brass section of the orchestra

increased; many special orchestral effects introduced; rich and colourful orchestration

http://www.mostlywind.co.uk/romantic.html

Emphasis on lyrical melodies rich, often chromatic harmonies, use of discords

Sense of vagueness in tonality/ harmony, but also in rhythm and meter

Denser textures with bold dramatic contrasts, exploring a wider range of pitches and

dynamics

Shape was brought to compositions through the use of recurring themese, such as

nature, region and nationalism (what the hell)

Musical Features in Prelude in C Sharp Minor

Self Analysis

Relative major of C# minor is E major. In reference to the Russian Submediant

Very large range of dynamics, ranging from ppp to sffff

http://www.pianoworld.com/forum/ubbthreads.php/topics/425072/Rachmaninoff's

%20Prelude%20in%20No%202.html

Use of German augmented sixth chord (ADF#B#) (predominant-functioned chords)

Usage of unusual tonal chords

Contradictions in Rachmaninov

Next comes one of Rachmaninovs most characteristic gestures great leaps,

alternating octaves with chords and soucnding like a massive bell (bar 9 [First Piano

Concerto]). This figure is prominent in Rachmaninovs two most popular works the

Prelude op. 3 no. 2 and Second Piano Concerto op. 18. EMPHASIS OF

CHARACTERISTICS OF RACHMANINOVS COMPOSITION

Repetition, whether varied or not, plays a major role in Rachmaninovs music. His

supporters welcome not only frequent repetition within works a sticking point with

his detractors but also the reappearance of ideas from one work to the nest (eg. The

Dies Irae and sounds of bells). Rachmaninovs critics have identified this sharing of

motives, themes ad gestures between works as incontrovertible proof of a paucity of

ideas. In other words, recurrence of material, within or between works is, like big

tunes, a strength or weakness, depending on ones vantage point.

Guitar tab of the song (?!)

http://www.911tabs.com/tabs/s/sergei_rachmaninoff/prelude_in_c_sharp_minor_tab.htm#670

1268

Analysis of Comparison Compositions

Rimsky-Korsakov: Flight of the Bumblebee

Vigorous use of chromaticism

The first musical element that we consider is tempo. Fast tempos typically generate

excitement, energy, and action. Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakovs Flight of the Bumblebee

speeds along at a breakneck pace in order to capture the frenetic motions of a berserk

insect. In contrast, slow tempos are often, but not always, used in solemn, deeply

reflective, and brooding situations. Richard Strauss Death and Transfiguration crawls

along at a lethargic pace, transporting the listener to a room housing a man on his

deathbed

Tchaikovsky: Swan Lake, Act II No. 10

Dramatic variation in dynamics

Very lyrical and emotive melodies

Rimsky-Korsakov: Scheherazade (Second Movement) (from two websites)

This is a Russian Orientalist symphonic suite

Originally, the four movements were going to be called Prelude, Ballade, Adagio and

Finale, but as the composition tended more to the programmatic side (more detailed

than Tchaikovskys Hamlet), he changed the titles of each movement

The orchestration is very strategic: he introduces the percussion instruments

gradually, which is exceptional for some reason.

Written in 1888

This piece of work was inspired by The Arabian Nights, in which the Sultan marries

and executes a new wife, due to his loss of trust when his wife is disloyal to him. Yet,

when he meets Scheherazade, he eventually relents and falls in love with her, as she

had a plan to stop him using her brilliant storytelling dexterity. She would tell him a

story, which continued on for 1001 days. By then, he has grown to trust her.

Description of the movements (general)

The piece opens with the Sultan a big and burly theme filled with gravitas and ego,

to declare his dominance over his minors

The solo violin personifies Scheherazades voice, somewhat sounding like the sounds

made by a snake charmers. The harp plays three chords, which symbolizes the

hypnotic power Scheherazade carried in her tales.

The modulations in key symbolizes the turning points of her tales

The second movement (The Tale of the Kalendar Prince) opens with the solo violin,

which depicts the soft, flowing melody that is Scheherazades voice. The solo violin

part is more elaborate and ornamented. In this movement, Rimsky Korsakov makes

use of Middle-Eastern sounding solos in the woodwind instruments

http://www.allmusic.com/composition/scheherazade-symphonic-suite-for-orchestra-op-35mc0002364307

Rimsky-Korsakov suggested that "one might see a fight" when a martial variant of the

Sultan's theme enters, surrounded by nervous string oscillations, while a later section with

fluttering woodwinds and pizzicato string chords suggests "Sinbad's mighty bird, the Roc."

Find more about Russian Orientalism did that influence Rachmaninov at all?

EE Title(s):

Initial: How did Russian Nationalist Music melodically and harmonically influence Sergei

Rachmaninovs Prelude in C Sharp Minor?

+ Argument

Modified title: To what extent did Rachmaninov incorporate melodic and harmonic elements

from Russian Nationalist Music into his Prelude in C Sharp Minor?

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Rachmaninoff's Complete Songs: A Companion with Texts and TranslationsDa EverandRachmaninoff's Complete Songs: A Companion with Texts and TranslationsNessuna valutazione finora

- Shostakovich's Music for Piano Solo: Interpretation and PerformanceDa EverandShostakovich's Music for Piano Solo: Interpretation and PerformanceValutazione: 3 su 5 stelle3/5 (2)

- XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXDocumento3 pagineXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXapi-3707795100% (1)

- Dmitri Hvorovsky - in This Moonlit Night Lieder by Tchaikovsky, TaneyevDocumento26 pagineDmitri Hvorovsky - in This Moonlit Night Lieder by Tchaikovsky, TaneyevblobfinkelsteinNessuna valutazione finora

- Smetana's Discursive Archetypes in MusicDocumento6 pagineSmetana's Discursive Archetypes in MusicAlexandra BelibouNessuna valutazione finora

- Piano Lit 4 Ass 2Documento3 paginePiano Lit 4 Ass 2kennethNessuna valutazione finora

- Oriental Elements in Russian Music and Reception in Western EuropeDocumento9 pagineOriental Elements in Russian Music and Reception in Western EuropeMiguel Angel Aguirre IgoaNessuna valutazione finora

- Gallagher Alyssa Janacek PaperDocumento6 pagineGallagher Alyssa Janacek PaperAlyssaGallagherNessuna valutazione finora

- Mapeh Q1Documento10 pagineMapeh Q1Czarina D. AceNessuna valutazione finora

- Booklet NotesDocumento184 pagineBooklet NotesJosé TelecheaNessuna valutazione finora

- Rachmaninoff The BellsDocumento7 pagineRachmaninoff The Bellsana naomiNessuna valutazione finora

- Program Notes: 1. 2 Preludes by A. Scriabin (Arr: A. Fougeray)Documento3 pagineProgram Notes: 1. 2 Preludes by A. Scriabin (Arr: A. Fougeray)AlmeidaNessuna valutazione finora

- LAS MAPEH 10 Q1 W1 MusicDocumento6 pagineLAS MAPEH 10 Q1 W1 MusicJemalyn Hibaya LasacaNessuna valutazione finora

- English Texts For The Songs of Nicholas MedtnerDocumento21 pagineEnglish Texts For The Songs of Nicholas MedtnerDezheng KongNessuna valutazione finora

- FanfareDocumento6 pagineFanfareCarlBryanLibresIbaosNessuna valutazione finora

- Cello Concerto No. 1 in E-Flat Major, Op. 107Documento2 pagineCello Concerto No. 1 in E-Flat Major, Op. 107Christian MunawekNessuna valutazione finora

- Secondary Music 9 Q3 Week2finalDocumento11 pagineSecondary Music 9 Q3 Week2finalMichelle SoleraNessuna valutazione finora

- Gesamtkunstwerk - Total Art Work Epic, Spectacle, Modeled On Greek Drama MusicDocumento11 pagineGesamtkunstwerk - Total Art Work Epic, Spectacle, Modeled On Greek Drama MusicLin ShengboNessuna valutazione finora

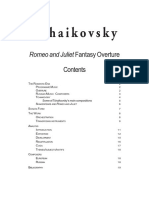

- Romeo and Juliet Fantasy OvertureDocumento19 pagineRomeo and Juliet Fantasy OvertureVirginie Perier Magnele75% (4)

- WIGGLERDocumento2 pagineWIGGLERCharles HancinNessuna valutazione finora

- The Five (Music)Documento4 pagineThe Five (Music)Tomek Maćków100% (1)

- MUC 323A - New Century Trends in Classical MusicDocumento2 pagineMUC 323A - New Century Trends in Classical MusicMitchell McVeighNessuna valutazione finora

- Music Music of The 20 Century: MapehDocumento26 pagineMusic Music of The 20 Century: MapehApril Sophie DavidNessuna valutazione finora

- MAPEH: A Guide to 20th Century Musical MovementsDocumento16 pagineMAPEH: A Guide to 20th Century Musical MovementsApril Sophie DavidNessuna valutazione finora

- Music Las 1 - Q1Documento7 pagineMusic Las 1 - Q1Justine Dave rubaNessuna valutazione finora

- Romantic Music (1850-1900) : Composers of The PeriodDocumento6 pagineRomantic Music (1850-1900) : Composers of The Periodann monteNessuna valutazione finora

- Great Russian Piano ComposersDocumento3 pagineGreat Russian Piano ComposersPetoleNessuna valutazione finora

- (брак) Norris Russian Piano concerto PDFDocumento280 pagine(брак) Norris Russian Piano concerto PDF2712760Nessuna valutazione finora

- Western Music Appreciation (II) - Week 1Documento18 pagineWestern Music Appreciation (II) - Week 1terriejohnny25Nessuna valutazione finora

- 20th Century Music StylesDocumento25 pagine20th Century Music StylesJeric MatunhayNessuna valutazione finora

- An Annotated Catalogue of The Major Piano Works of Sergei RachmanDocumento91 pagineAn Annotated Catalogue of The Major Piano Works of Sergei RachmanjohnbrownbagNessuna valutazione finora

- Mozart SongsDocumento6 pagineMozart Songscostin_soare_2Nessuna valutazione finora

- Rimsky-Korsakov Scheherazade NotesDocumento1 paginaRimsky-Korsakov Scheherazade NotesJoshua AlleyNessuna valutazione finora

- Landscapeçrhythmçmemory: Contexts For Mapping The Music of George EnescuDocumento45 pagineLandscapeçrhythmçmemory: Contexts For Mapping The Music of George EnescuchrisNessuna valutazione finora

- Roman Returns: Dvor Ák Cello Concerto: 30 Second NotesDocumento4 pagineRoman Returns: Dvor Ák Cello Concerto: 30 Second NotesKwangHoon HanNessuna valutazione finora

- Art and Music Have Developed in Parallel With Each Other: Impressionism Century 20th Century ImpressionismDocumento15 pagineArt and Music Have Developed in Parallel With Each Other: Impressionism Century 20th Century ImpressionismJiji Carinan - TaclobNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson 1 MusicDocumento71 pagineLesson 1 MusickitcathNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson 1-Music With QuizDocumento79 pagineLesson 1-Music With Quizkitcath100% (1)

- MAPEH ReviewerDocumento12 pagineMAPEH ReviewerCassandra Jeurice UyNessuna valutazione finora

- 20th Century MusicDocumento95 pagine20th Century MusicMer LynNessuna valutazione finora

- Richard Strauss (1864-1949) : Don Juan, Op. 20Documento7 pagineRichard Strauss (1864-1949) : Don Juan, Op. 20Rut Moreno CalderónNessuna valutazione finora

- Capriccio For Piano and Orchestra Igor Stravinsky: in ShortDocumento2 pagineCapriccio For Piano and Orchestra Igor Stravinsky: in ShortDavi Raubach TuchtenhagenNessuna valutazione finora

- First Quarter Music10Documento63 pagineFirst Quarter Music10Ysabelle TagarumaNessuna valutazione finora

- Stravinsky Capriccio For Piano and Orchestra PDFDocumento2 pagineStravinsky Capriccio For Piano and Orchestra PDFDianaNessuna valutazione finora

- DipABRSM Programme NotesDocumento5 pagineDipABRSM Programme Notesmpbhyxforever33% (3)

- Notes Beethoven WebDocumento3 pagineNotes Beethoven WebJose Javier ZafraNessuna valutazione finora

- Romeo and Juliet Fantasy OvertureDocumento19 pagineRomeo and Juliet Fantasy OvertureWilliam Wolfang100% (1)

- The Romantic Period 2018Documento5 pagineThe Romantic Period 2018Rebecca AntoniosNessuna valutazione finora

- CHANDocumento12 pagineCHANEdelweiss_AngelNessuna valutazione finora

- Tchaikovsky Symphony5Documento3 pagineTchaikovsky Symphony5MarijanaDujovicNessuna valutazione finora

- Knaifel Alexander BiographyDocumento1 paginaKnaifel Alexander BiographyIma BageNessuna valutazione finora

- Nocturne (Fr. of The Night Ger. Nachtstück It. Notturno)Documento2 pagineNocturne (Fr. of The Night Ger. Nachtstück It. Notturno)EENessuna valutazione finora

- Romantic Music Is A Stylistic Movement In: BackgroundDocumento6 pagineRomantic Music Is A Stylistic Movement In: BackgroundMixyNessuna valutazione finora

- Chamber Music - WikipediaDocumento27 pagineChamber Music - WikipediaElenaNessuna valutazione finora

- Life and General Presentation of Style and CreationDocumento4 pagineLife and General Presentation of Style and CreationalinsdsdsdNessuna valutazione finora

- Stravinskys Compositions For Wind Instru PDFDocumento13 pagineStravinskys Compositions For Wind Instru PDFMarildaPsilveiraNessuna valutazione finora

- Pjotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) : SymphoniesDocumento25 paginePjotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) : SymphoniesOrlandoSlavNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 Kushner Aram Khachaturian (1903 1978) A RetrospectiveDocumento28 pagine1 Kushner Aram Khachaturian (1903 1978) A RetrospectiveMinjie Liu100% (3)

- Mapeh Grade 10 Module 1Documento12 pagineMapeh Grade 10 Module 1Jorely Barbero Munda100% (7)

- Neoclassical Music Composers and Their WorksDocumento2 pagineNeoclassical Music Composers and Their WorksIrishman70880% (5)

- Developing Agility Vocal Flexibility and Velocity FacilityDocumento2 pagineDeveloping Agility Vocal Flexibility and Velocity Facilitymarilena ChristofiNessuna valutazione finora

- Improvisator ManualDocumento27 pagineImprovisator ManualAndrés ClaimanNessuna valutazione finora

- Saxophone Technique PDFDocumento22 pagineSaxophone Technique PDF谢重霄Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ceremonium 3 2 2: Chimes 3Documento2 pagineCeremonium 3 2 2: Chimes 3DariaNessuna valutazione finora

- Lord, Here I Am: Cielo Almazan, OFM / Renato HebronDocumento2 pagineLord, Here I Am: Cielo Almazan, OFM / Renato HebronAmiel TapanNessuna valutazione finora

- Look Inside The Score PDFDocumento12 pagineLook Inside The Score PDFclassicalmprNessuna valutazione finora

- Ethiopian Music Scales and Song TypesDocumento3 pagineEthiopian Music Scales and Song TypesCWJEF ScoresNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 - ChamberMusicRepList1Documento12 pagine1 - ChamberMusicRepList1QuangclaNessuna valutazione finora

- Railroad Travel SongDocumento3 pagineRailroad Travel Songstoneramirez12300Nessuna valutazione finora

- NVCEDocumento2 pagineNVCEKCNessuna valutazione finora

- (Lost Frequencies) Reality - Tuấn Sáng TốiDocumento3 pagine(Lost Frequencies) Reality - Tuấn Sáng TốiNgoc Hieu NguyenNessuna valutazione finora

- Muse355 CmupDocumento10 pagineMuse355 Cmupapi-284200347Nessuna valutazione finora

- Analysis Examples - Webern Op. 21 and 24 - OPEN MUSIC THEORYDocumento1 paginaAnalysis Examples - Webern Op. 21 and 24 - OPEN MUSIC THEORYLuna100% (1)

- Vinai 20melodicballadlicks Lick16 TabDocumento3 pagineVinai 20melodicballadlicks Lick16 TabVinnie HeNessuna valutazione finora

- Watermelonman BB PDFDocumento1 paginaWatermelonman BB PDFAaromNessuna valutazione finora

- John Thompson Modern Course For Piano - 1st GradeDocumento82 pagineJohn Thompson Modern Course For Piano - 1st GradeJuan Carlos Martinez MNessuna valutazione finora

- Rubrics Kompang EnsembleDocumento2 pagineRubrics Kompang EnsembleNURUL IZZAH KAMAR BASHAHNessuna valutazione finora

- Double Bass Double Stop ExercisesDocumento2 pagineDouble Bass Double Stop ExercisesClaudioNessuna valutazione finora

- What Is Melodic ContourDocumento3 pagineWhat Is Melodic ContourCynthia UnayNessuna valutazione finora

- TBBY1Documento66 pagineTBBY1bopdubNessuna valutazione finora

- Danny Boy Arranged for Mixed ChoirDocumento4 pagineDanny Boy Arranged for Mixed ChoirYoga PranataNessuna valutazione finora

- Hark! The Herald Angels Sing (Jazz Piano Arrangement)Documento2 pagineHark! The Herald Angels Sing (Jazz Piano Arrangement)maherjubli100% (1)

- The Ultimate Guide To The Modes of The Major Scale For Bass PDFDocumento16 pagineThe Ultimate Guide To The Modes of The Major Scale For Bass PDFsqueekymccleanNessuna valutazione finora

- San Miguel Elementary Music TestDocumento2 pagineSan Miguel Elementary Music TestSherra MonteroNessuna valutazione finora

- Dreamy Night Deluxe EditionDocumento4 pagineDreamy Night Deluxe EditionWren GalinganaNessuna valutazione finora

- Kaleidoscope: - Q 'R JQ - Q A Q + eDocumento6 pagineKaleidoscope: - Q 'R JQ - Q A Q + ePeter Gore-SymesNessuna valutazione finora

- ThawerDocumento3 pagineThawerradicalsurge100% (2)

- Violin 2020 Grade 8 PDFDocumento18 pagineViolin 2020 Grade 8 PDFSam Cheng100% (1)

- Travis PickingDocumento5 pagineTravis Pickinganzrocknroll100% (2)

- Ap Music Theory Exam 2020 Sample QuestionsDocumento5 pagineAp Music Theory Exam 2020 Sample QuestionsOrlando RomanNessuna valutazione finora