Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Appeal Case Disputes Ownership of 58 Acres of Land in Selangor

Caricato da

Rita LakhsmiTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Appeal Case Disputes Ownership of 58 Acres of Land in Selangor

Caricato da

Rita LakhsmiCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Page 1

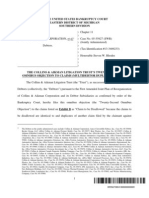

ICLR: Appeal Cases/1913/LOKE YEW DEFENDANT; AND PORT SWETTENHAM RUBBER COMPANY,

LIMITED PLAINTIFFS. ON APPEAL FROM THE COURT OF APPEAL OF SELANGOR (FEDERATED

MALAY STATES). - [1913] A.C. 491

[1913] A.C. 491

[PRIVY COUNCIL.]

LOKE YEW DEFENDANT; AND PORT SWETTENHAM RUBBER COMPANY, LIMITED

PLAINTIFFS. ON APPEAL FROM THE COURT OF APPEAL OF SELANGOR

(FEDERATED MALAY STATES).

1913 Jan. 30, 31; Feb. 25; March 19.

LORD ATKINSON, LORD SHAW OF DUNFERMLINE, and LORD MOULTON. LORD MACNAGHTEN*.

Registration of Titles Regulation, 1891 (Reg. IV. of 1891, State of Selangor), s. 7 - Fraud - Knowledge of

Unregistered Rights - Rectification - Trustee - Specific Relief Enactment, 1893 (Enact. IX. of 1903), s. 3,

Illustration (g).

The Registration of Titles Regulation, 1891, provides for the registration of all titles to land in the State of

Selangor, and by s. 7 provides that the title of the person named in the certificate of title issued thereunder

shall be indefeasible except on the ground of fraud or misrepresentation or of adverse possession for the

prescriptive period. In June, 1910, one Eusope was the registered owner of 322 acres of land in Selangor, as

to 58 acres of which the appellant was in possession under unregistered Malay documents constituting him

the owner subject to the payment of an annual rent to Eusope. The respondents, who had knowledge of the

appellant's interest, bought from Eusope the 322 acres excepting the said 58 acres. A transfer of the whole

322 acres was prepared, and in order to induce Eusope to sign it the respondents' agent told him that if he

did so the respondents would purchase the appellant's interest, and signed a document which stated "As

regards Loke Yew's interest I shall have to make my own arrangements." Eusope thereupon signed the

transfer. The respondents, having obtained thereunder registration of the entire 322 acres, called upon the

appellant to give up possession of the 58 acres, and upon his failing to do so commenced an action, claiming

possession thereof and damages. The appellant asked for rectification:Held, that the action should be dismissed and the respondents ordered to execute and register in the

appellant's name a grant of the 58 acres subject to the rent reserved, on the grounds -

(1.)

that, on the facts, the respondents obtained the transfer by fraud and misrepresentation.

(2.) That, apart from the exception in s. 7, as the rights of third parties did not intervene, the

respondents could not better their position

Page 2

LORD MACNAGHTEN, who was present on January 30 and 31, died on February 17.

[1913] A.C. 491 Page 492

by obtaining registration under circumstances which made it not honest to do so, and that it

was the duty of the Court to order rectification.

(3.) That under the Specific Relief Enactment, 1903, s. 3, the respondents having bought

with notice of the appellant's rights were trustees for him in respect thereof.

APPEAL from an order (July 24, 1911) of the Court of Appeal of the State of Selangor (Federated

Malay States) reversing an order (November 21, 1910) of the Court of the Judicial Commissioner at

Kuala Lumpur.

The action was for ejectment and to recover possession of certain land in Selangor. The land in

dispute consisted of about fifty-eight acres forming part of a block of 322 acres known as grant 675,

which was on January 4, 1894, granted under the Selangor Land Code, 1891, to Haji Mohamed

Eusope, "to hold for ever" subject to an annual rent of about 10 cents an acre to the Sultan of

Selangor, his heirs and successors. This grant was registered under the provisions of the

Registration of Titles Regulation, 1891 (Reg. IV. of 1891) (1), and Haji

(1)

The following are the more material portions of the Registration of Titles Regulation, 1891:-

Sect. 4: "After the coming into operation of this regulation, all land which is comprised in any grant, whether issued

prior or subsequent to the coming into operation of this regulation, shall be subject to this regulation, and shall not

be capable of being transferred, transmitted, mortgaged, charged, or otherwise dealt with except in accordance with

the provisions of this regulation, and every attempt to transfer, transmit, mortgage, charge, or otherwise deal with

the same, except as aforesaid, shall be null and void and of none effect."

Sect. 7: "The duplicate certificate of title issued by the registrar to any purchaser of land upon a genuine transfer or

transmission by the proprietor thereof shall be taken by all Courts as conclusive evidence that the person named

therein as proprietor of the land is the absolute and indefeasible owner thereof, subject to the conditions and

agreements expressed or implied in the original grant, and the title of such proprietor shall not be subject to

challenge, except on the ground of fraud or misrepresentation to which he is proved to be a party, or on the ground

of adverse possession in another for the prescriptive period."

Sect. 21: "Except as is hereinafter otherwise provided .... instruments registered in respect of or affecting the same

land shall notwithstanding any express implied or constructive notice be entitled to priority according to the date of

registration and not according to the date of each instrument itself. ..."

Sect. 68: "Any person claiming to be interested under any will, settlement, or trust deed, or any instrument of

transfer or transmission, or under any unregistered instrument, or otherwise howsoever in any land,

Page 3

[1913] A.C. 491 Page 493

Mohamed Eusope was the registered owner of the whole 322 acres under that regulation. During

1895 and 1896 Eusope subdivided the 322 acres into allotments of from one to four acres and

disposed of them to Malay cultivators at an increased annual rent. Each of these cultivators

received from Eusope a document in the Malay language. The documents were all in the same

form and gave to each cultivator an absolute right to enjoy the land for the period in the original

grant, that is, for ever, subject to the payment of a rent of $1.25 to the holder of the original grant.

Between 1899 and 1909 the appellant, a Chinese, with the assent of Eusope purchased from the

Malay cultivators fifteen of these allotments for a total sum of $7716. From each cultivator the

appellant received a document in the Malay language signed by the cultivator and by Eusope.

These documents were all in the same form and referred to the allotment as being sold by the

cultivator to the appellant and as forming part of the original grant. The appellant took possession of

these fifteen allotments, which together made about fifty-eight acres and were the subject-matter of

the litigation, and he duly paid the annual rents reserved to Eusope. No steps were taken to register

any of the Malay documents under s. 7 or to protect them by caveat under s. 68 of the Registration

of Titles Regulation, 1891.

In 1910 the respondents, who had knowledge of the transactions above referred to, opened

negotiations with Eusope for the purchase of the whole 322 acres comprised in the original grant,

and Eusope bought back from the Malay cultivators for about $115,000 all the allotments except

the fifteen held by the appellant and seven further acres which had been acquired by a Chinese

partnership called Sz Woh Kongsi.

____________

may lodge a caveat with the registrar to the effect that no disposition of such land be made either absolutely or in

such manner and to such extent only as in such caveat may be expressed, or until notice shall have been served on

the caveator or unless the instrument of disposition be expressed to be subject to the claim of the caveator as may

be required in such caveat, or to any conditions conformable to law expressed therein. ...."

Sect. 86: "Nothing contained in this regulation shall take away or affect the jurisdiction of the Court on the ground of

actual fraud."

[1913] A.C. 491 Page 494

Early in June, 1910, the respondents agreed to purchase from Eusope the whole of the 322 acres,

except the appellant's fifty-eight acres, for $350,000, and on June 4 the representatives of the

appellant and of the respondents met to complete the sale. It was agreed that out of the price

$14,000 should be retained, being an amount agreed to be accepted by the Chinese partnership in

respect of their seven acres, payment thereof being deferred till the conclusion of litigation between

the members of the partnership.

The respondents' local solicitors had prepared a transfer purporting to transfer the whole 322 acres

without exception to the respondents' trustees; this Eusope refused to sign unless he received an

agreement on the part of the respondents not to disturb the appellant in his possession. Mr. Glass,

Page 4

the respondents' agent, assured Eusope that he need not be afraid, as he would purchase the

appellant's interest. Eusope, however, pressed for something in writing, and Mr. Glass signed a

document to the effect that he had purchased the land comprised in grant 675, adding, "as regards

Loke Yew (the appellant) and Kongsi's land which is included in the said grant I shall have to make

my own arrangements." Their Lordships found that this was a statement of a present intention and

was false and fraudulently made for the purpose of inducing Eusope to execute a transfer of the

whole 322 acres comprised in the grant.

Upon receipt of this document Eusope signed a formal transfer in the statutory form required by the

Registration of Titles Regulation, 1891, for the whole 322 acres comprised in the grant. This

transfer was to Glass, and was shortly afterwards registered. Subsequently Glass transferred the

land to the respondents, who registered the transfer. No duplicate certificate under the Registration

of Titles Regulation, 1891, s. 7, was issued to the respondents, but a memorial under s. 28 was

indorsed upon the original grant to Eusope. On June 22, 1910, the respondents' solicitors wrote to

the appellant a letter in which, while not admitting that the appellant had any rights in the fifty-eight

acres, they offered him $20,000 for the surrender of any rights which he claimed. This offer was

declined. On August 18,1910, the respondents gave the appellant notice to quit the land, and on

[1913] A.C. 491 Page 495

August 29, 1910, the appellant commenced proceedings under s. 72 of the Registration of Titles

Regulation, 1891, for the purpose of having the respondents' documents of title to the 322 acres

rectified by excluding therefrom the fifty-eight acres now in dispute. The progress of this suit was

stayed pending the decision of the present appeal.

On August 24, 1910, the respondents commenced the present suit, alleging that they were

registered owners of the whole 322 acres and claiming possession and damages. The appellant by

his defence claimed title to occupy the land in dispute by virtue of the Malay documents and

pleaded that the respondents had taken their transfer with full knowledge of the appellant's title and

rights and that their conduct amounted to fraud within the Registration of Titles Regulation, 1891, s.

7. He also claimed that the respondents' registered title should be rectified and that the land in

dispute should be assured to him by a proper registered transfer. The appellant also pleaded that

the suit was barred by the Limitation Enactment, 1896, but the decision of this point became

unnecessary and the arguments thereon are omitted from this report.

The action was heard by the Judicial Commissioner on September 21, 22, and 23, 1910, and on

November 21, 1910, he gave judgment dismissing the respondents' suit and ordering that they, on

the footing of being trustees for the appellant, should execute and register in his favour a grant of

the fifty-eight acres in dispute subject to the annual rent reserved. The Judicial Commissioner found

(and it was admitted) that the respondents took their transfers with actual notice of the appellant's

rights; he also found that they paid nothing in respect of the fifty-eight acres in dispute. He was of

opinion that the respondents did not gain an indefeasible title under the Registration of Titles

Regulation, 1891, s. 7, as the probative force of a memorial of transfer entered upon the registered

grant under s. 28 was not the same as an actual certificate of title under s. 7, and that accordingly it

was not necessary to find fraud within the latter section in order to avoid the respondents' title. He

further held that s. 4 did not render the Malay documents nullities, but only prevented their

operation as legal transfers, and that they

[1913] A.C. 491 Page 496

were contracts which could be enforced against the respondents, who had purchased with notice.

Notices of appeal and of cross-appeal were given. The appeal and cross-appeal were heard by the

Court of Appeal of Selangor, and on July 24, 1911, judgment was given allowing the respondents'

appeal, and an order was made for possession of the land in dispute and for an inquiry as to

Page 5

damages. The learned judges of that Court adopted the findings of fact of the Judicial

Commissioner, but differed from him as to the effect of the indorsement of a memorial under s. 28,

which they held was as effectual to give an indefeasible title as a certificate under s. 7, and they

further held that the Malay documents were absolute nullities and conferred no right or interest

upon the appellant of which he could be deprived by fraud or otherwise.

Buckmaster, K.C., and Alfred Adams, for the appellant. It is only a certificate of title which, under the

Registration of Titles Regulation, s. 7, carries a title indefeasible except in the case of fraud or adverse

possession for the prescriptive period. There is no provision that a memorial under s. 28 has the same effect,

and it was not necessary for the appellant to prove fraud. If, however, s. 7 is to be taken as applying to a

memorial as well as to a certificate, the evidence shews that there was fraud within the meaning of that

section, as well as "actual fraud" within s. 86. The respondents' agent obtained the transfer of the entire 322

acres by a representation, both verbal and in writing, the effect of which was that there was an intention to

settle with the appellant in respect of his interest. The inference to be drawn from the evidence is that there

was not any such intention and that the statement was fraudulently made for the purpose of obtaining a

transfer of the whole 322 acres. But apart from this the conduct of the respondents in registering the transfer

with knowledge of the appellant's rights was fraud within s. 7 of the Regulation. Similar conduct is described

by Lord Hardwicke in Le Neve v. Le Neve (1) as "a species of fraud and dolus malus itself," and it was so

held with regard to the registration of a

(1)

(1747) Amb. 436 (a); 2 W. & T. L. C. (8th ed.) at p. 196.

[1913] A.C. 491 Page 497

deed in Natal in Crowly v. Bergtheil. (1) The decision in Assets Co. v. Mere Roihi (2) is not applicable, the

registration being obtained in that case bona fide, and no question arose as to registration with knowledge of

an outstanding title. In various colonies in which there are provisions for registration of title there has been a

conflict of judicial authority upon this point: see Hogg's Australian Torrens System, 1905, p. 836. The Malay

instruments cannot be treated as nullities. Though ineffectual as transfers for want of registration, the law will

give effect to them as contracts: Shep. Touch., c. 24, p. 514; Mouys v. Leake (3); Parker v. Taswell (4);

Tailby v. Official Receiver (5); as to the effect of part performance upon an unregistered transfer see White v.

Neaylon. (6) They are enforceable against the respondents, who purchased with knowledge and subject to

the appellant's rights thereunder. Under the Specific Relief Enactment, 1903, s. 3, Illustration (g), the

respondents, having notice, became trustees for the appellant, and they can be ordered to give effect to the

rights of their cestui que trust. The intention of the Malay grants can be carried out by registered instruments

in accordance with the Regulation. Sects. 7 and 25 shew that a transfer may be made subject to agreements

or conditions on the part of the transferee, and this includes an agreement to pay a rent-charge.

Upjohn, K.C., and Sargant, for the respondents. The effect of a memorial under s. 28 is the same as that of

a certificate under s. 7, and that section must be so read. It is at the option of the registrar whether he shall

issue a certificate or merely indorse a memorial, and it cannot be that the character of the title differs

according to which course he adopts. The respondents have therefore under s. 7 a title indefeasible except

on the ground of fraud or continued adverse possession. There was no fraud. The respondents purchased

subject to the appellant's rights so far only as they were enforceable rights. Fraud cannot be attributed to a

purchaser because he disregards a

Page 6

(1)

[1899] A. C. 374.

(2)

[1905] A. C. 177.

(3)

(1799) 8 T. R. 411, at p. 415.

(4)

(1858) 2 De G. & J. 559.

(5)

(1888) 13 App. Cas. 523, at p. 543.

(6)

(1886) 11 App. Cas. 171.

[1913] A.C. 491 Page 498

claim which is unenforceable and based on a nullity, as the appellant's claim was, having regard to ss. 7 and

25 of the Regulation. So far as the Malay instruments gave the appellant any rights in law it was in contract

against Eusope; his only possible right against the respondents is a right in equity. As appears, however,

from a review of the Registration of Titles Regulation, 1891, and especially from s. 68, under which a caveat

could have been entered, the intention of the Legislature was to exclude those equitable rights to which

effect would be given in English law as against a purchaser with notice: Assets Co. v. Mere Roihi. (1) Sect.

21 of the Regulation provides that priority between registered titles is to be according to the date of

registration notwithstanding any notice, and it is a fortiori as between a registered and an unregistered title.

Registration of title with actual notice does not necessarily involve fraud: Battison v. Hobson. (2) No relief can

be given in equity against a legal invalidity which is caused by direct and positive statutory enactment:

Edwards v. Edwards (3); London and South Western Ry. Co. v. Gomm. (4) The appellant is not entitled to

any relief against the respondents under the Specific Relief Enactment, 1903, because his interest being

unregistered is not enforceable. Where, as here, the alleged cestui que trust is a rival claimant who can

prove no trust apart from his own alleged ownership, to treat him as a cestui que trust would be to destroy all

benefit from registration: Assets Co. v. Mere Roihi. (5) Sect. 3, Illustration (g), of the Enactment is subject to

s. 4, which expressly preserves the application of the law as to registration of title.

Buckmaster, K.C., in reply.

The judgment of their Lordships was delivered by

LORD MOULTON . This is an action of ejectment brought by the Port Swettenham Rubber Company,

Limited, against Loke Yew to recover possession of a piece of land situated in the State of Selangor. The

statement of plaint alleges that the plaintiff company is the registered owner of the land, that there is no

Page 7

(1)

[1905] A. C. 177.

(2)

[1896] 2 Ch. 403.

(3)

(1876) 2 Ch. D. 291.

(4)

(1882) 20 Ch. D. 562.

(5)

[1905] A. C. at p. 204.

[1913] A.C. 491 Page 499

incumbrance upon it, and that the defendant has no title to occupy it. It admits that the defendant is in fact in

occupation, but alleges notice to quit and refusal by the defendant to go out. The statement of defence

alleges title in the defendant, and that the registered title of the plaintiffs was obtained by fraud, and also

pleads possession for twelve years before the commencement of the suit, so that the plaintiff's right of action

is barred by the Limitation Enactment V. of 1896. The meaning and significance of the allegations in the

defence can only be understood by a reference to the history of the land in question and the transactions

relating to it.

On January 4, 1894, the Resident of Selangor under and by virtue of the power conferred upon him by the

Selangor Land Code, 1891, in the name and on behalf of the Sultan of Selangor, made a grant of a piece of

land in Kland, containing about 323 acres, to Haji Mohamed Eusope. The consideration for the grant was the

sum of $323, and an annual rent. The terms of the grant were: "To hold for ever, subject to the payment to

his said Highness, his heirs and successors, therefor of the annual rent of thirty-two dollars and thirty cents,

and to the provisions and agreements contained in the said Code."

Haji Mohamed Eusope having obtained the grant proceeded to dispose of portions of the land comprised in it

to cultivators, who seem to have laboured the land and brought it under cultivation. The documents effecting

the transactions in each case are in the Malay language, and are all in the same form. Taking, for example,

the one exhibited in the action, namely, the transfer of about 4 acres to Yeop Sow San, the operative

words (as translated) are as follows: "Now I have truly given to Yeop Sow San the right to hold a portion of

the said land on the same conditions that I hold it from the Government of Selangor - Yeop Sow San obtains

from me the right to hold the land on the same condition, that is, he can sell it, he can mortgage it, and he

can bequeath it to his heirs for the period mentioned in the big grant, that is - years. But during the said

period, Yeop Sow San, or whoever, after him, having the right to hold the land by purchase or otherwise,

must pay rent to me or, after me, to whomsoever that obtains the

[1913] A.C. 491 Page 500

right to hold the big grant, that is, $1.25 for an acre every year."

Although this grant may not be in a form such as would be used by skilled conveyancers, its language is

clear, and their Lordships have no doubt as to its meaning or effect. It is perhaps best described as a

sub-infeudation. The owner of the head grant parts with the whole of his interest in the specified portion of

the land for a payment of money, and an annual rent or feu. There is no reversion, because the grant is for

Page 8

the same period as the head grant, i.e., is a grant in perpetuity. Had this instrument been registered, it would

thereupon have given to the grantee the whole of the interest in the specified land possessed by the holder

of the head grant, and thus would have effectively carved out of the land included in the original grant the

portion covered by the derivative grant. But owing to the provisions of Regulation 4 of 1891, which is entitled

"A Regulation to provide for the Transfer of Land by Registration of Title," no instrument is effective to convey

any estate in land unless it is registered, and therefore the effect of the instrument rested in contract until

registration.

At various dates in and between December, 1906, and January, 1909, the defendant Loke Yew purchased

fifteen of these sub-grants from their owners, and thus became possessed of an area of about fifty-eight

acres of land, comprised in the original grant. Certain other portions were acquired by a Chinese partnership

called Sz Woh Kongsi. Other sub-grants of portions of the land were also created by Haji Mohamed Eusope,

but as these were subsequently bought back by him for a sum of about $114,000, prior to the transaction

between him and the plaintiff company about to be referred to, there is no need to make any further

reference to them.

In the year 1910 the plaintiff company formed the project of acquiring the land included in the grant to Haji

Mohamed Eusope, and commenced negotiations with him for that purpose. They had full knowledge of all

the transactions above referred to. For the purpose of the sale he purchased back all his sub grants with the

exception of those in the hands of the defendant Loke Yew and the Sz Woh Kongsi. He sought to acquire in

the

[1913] A.C. 491 Page 501

same way those that were in the hands of the defendant, but the defendant refused to part with his grants.

The Sz Woh Kongsi, on the other hand, were willing to sell their grants for $14,000 - the only difficulty being

that, by reason of a lawsuit among the members of the partnership, it was uncertain in what proportions and

to what members of the partnership that $14,000 would eventually be distributed. The difficulty was met, as

will presently be seen, by an allowance of the $14,000 out of the price paid by the plaintiff company - they

holding the sum so retained by them for the purpose of distribution among the members of the Sz Woh

Kongsi so soon as the shares should have been ascertained in the litigation.

The negotiations between the plaintiff company and Haji Mohamed Eusope were carried on by a certain Mr.

Glass as agent on behalf of the company. The evidence shews that Haji Mohamed Eusope recognized

throughout that he had parted with his interest in the Loke Yew lands (excepting the right to receive the

annual payments or feus), and that it was arranged originally that the conveyance to the plaintiff company

should not include Loke Yew's land. The price excluding that land was fixed at $350,000. The deed of

conveyance, however, purported to convey the original grant in its entirety. Haji Mohamed Eusope, who

appears to have acted honestly throughout, refused to sign that conveyance without a document shewing

that he was not selling Loke Yew's land, and originally a lengthy document to that effect was drawn up for

him by a conveyancer, which he asked Mr. Glass to sign. This document, however, Mr. Glass refused to

sign, apparently because of objections taken to it by the representative of the bank who was in charge of the

money to be paid as the purchase price. But Haji Mohamed Eusope would not proceed without an assurance

that the lands of Loke Yew and Sz Woh Kongsi were not included in the sale. Mr. Glass then replied that he

need not be afraid, as he knew Loke Yew, and would purchase his interest.

Haji Mohamed Eusope required, however, something in writing, and accordingly the following document was

written out and signed by Mr. Glass:[1913] A.C. 491 Page 502

"To Haji Mohamed Eusop bin Abubakar.

Page 9

I have purchased the land comprised in Grant No. 675 of Mukin Klang in the District of Klang for the sum of

$336,000.

"As regards Loke Yew and See Oh Kongsee's land which is included in the said grant I shall have to make my own

arrangements.

Kuala Lumpur.

(Signed) Philip J. Glass.

4th June 1910.

Signed in the presence of

(Signed) G. H. Day.

Lease:

Nos. 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 33,

36, 40, 42, 43, 50,

59, 82, 83, 84 & 2."

Their Lordships have no doubt that the true conclusion to be drawn from the evidence is that the above

statement of Mr. Glass to Haji Mohamed Eusope was intended to be and was a statement as to present

intention as well as an undertaking with regard to the future, and that that statement was false and

fraudulently made for the purpose of inducing Haji Mohamed Eusope to execute a conveyance which in form

comprised the whole of the original grant, and that but for such fraudulent statement that conveyance would

not have been executed. At that time it is evident that Mr. Glass intended to eject Loke Yew if he did not

accept whatever sum he chose to offer, and that therefore he did not intend to purchase Loke Yew's rights. It

is also clear that it was understood, and intended by Mr. Glass that it should be understood, that the

document above set out was written (to use the words of one of the witnesses) "for the security of the vendor

to shew that he was not selling Loke Yew's land," and their Lordships are of opinion that the document

carries out that intention. The purchase price there mentioned of $336,000 makes allowance for the $14,000

to be paid for the land of Sz Woh Kongsi which is the last of the parcels noted in the margin and called

therein "lease," the other fifteen being the numbers of the sub-grants held by Loke Yew. It is important in this

connection to note that the purchase price inserted in the conveyance is $417,000, shewing a difference of

[1913] A.C. 491 Page 503

$67,000 when compared with the sum actually paid after allowing for the $14,000 for the land of Sz Woh

Kongsi. This corresponds closely with the plaintiff company's own estimate of $70,000 as the value of Loke

Yew's land which appears elsewhere in the suit. It is clear, therefore, from the amount actually paid that Loke

Yew's lands were not included in the sale.

Having thus possessed himself of a formal transfer of the original grant to himself as trustee for the Port

Swettenham Rubber Company, Limited, Mr. Glass procured its registration, and thereupon the solicitors for

Page 10

the plaintiffs wrote to Loke Yew the following letter:Kuala Lumpur, Selangor,

Federated Malay States,

22nd June 1910.

Dear Sir,

On behalf of the Port Swettenham Rubber Company, Limited, we are instructed to inform you that our clients

have bought the land comprised in Grant 675, and we are further instructed to ask you to give directions to

your coolies to cease from entering on this land and tapping the trees thereon. We are informed that you

have an agreement of some nature with the former owner of this land, and that though our clients do not

admit, and in fact deny, that you have any right against any person whatsoever under this agreement, yet to

prevent any unpleasantness our clients are willing to pay you the sum of $20,000 if you will surrender to

them any rights you claim under the said agreement.

Yours faithfully,

Hewgill and Day.

Towkay Loke Yew."

and on the defendant's refusing to vacate the land the plaintiffs brought the present action for ejectment.

Their Lordships therefore find that the formal transfer of all the rights under the original grant was obtained

by the deliberate fraud of Mr. Glass. He was aware that he could not obtain the execution of a transfer in that

form otherwise than by fraudulently representing that there was no intention to use it

[1913] A.C. 491 Page 504

until the plaintiff company were able so to do honestly by having acquired Loke Yew's sub-grants by

purchase, and he therefore fraudulently made such representation, and thereby obtained the execution of

the transfer. It is an important fact to be borne in mind that although this fraud was clearly charged in the

defence, Mr. Glass was not called at the trial, nor was his absence accounted for. The inference to be drawn

from this is obvious and is entitled to great weight.

The case of the plaintiffs as argued before their Lordships rested mainly on the effect of registration. At the

date of the writ the transfer to the plaintiffs was registered while the sub-grants of Haji Mohamed Eusope

held by Loke Yew were not. Counsel for the plaintiffs therefore argued that under the provisions of the

Registration of Titles Regulation the plaintiffs possessed an indefeasible title to the land, and that under the

provisions of s. 4 all the sub-grants were "null and void and of none effect." A memorial of the transfer had

been made upon the duplicate grant under the provisions of s. 28, and they contended that that was

equivalent to a certificate of title under s. 6 and that by virtue of s. 7 this was "conclusive evidence that the

person named therein as proprietor of the land is the absolute and indefeasible owner thereof."

Page 11

The conclusion to which their Lordships have come as to the transfer having been obtained by fraud brings

the case within the exception of s. 7 and is therefore a sufficient answer to these arguments. But their

Lordships are of opinion that for other reasons they are irrelevant and beside the mark. They take no account

of the power and duty of a Court to direct rectification of the register. So long as the rights of third parties are

not implicated a wrong-doer cannot shelter himself under the registration as against the man who has

suffered the wrong. Indeed the duty of the Court to rectify the register in proper cases is all the more

imperative because of the absoluteness of the effect of the registration if the register be not rectified. Take

for example the simple case of an agent who has purchased land on behalf of his principal but has taken the

conveyance in his own name, and in virtue thereof claims to be the owner of the land whereas in truth he is a

bare trustee for his principal. The Court can order him

[1913] A.C. 491 Page 505

to do his duty just as much in a country where registration is compulsory as in any other country, and if that

duty includes fresh entries in the register or the correction of existing entries it can order the necessary acts

to be done accordingly. It may be laid down as a principle of general application that where the rights of third

parties do not intervene no person can better his position by doing that which it is not honest to do, and

inasmuch as the registration of this absolute transfer of the whole of the original grants was not an honest act

under the circumstances it cannot better the position of the plaintiffs as against the defendant and they

cannot rely on it as against him when seeking to enforce rights which formally belong to them only by reason

of their own fraud. It must be remembered that in the present case the defendant immediately on the bringing

of the action applied to rectify the register and that such rectification only awaits the event of this suit. His

right to it is set up in the defence, so that he has taken all the necessary steps to obtain the full relief to which

he is entitled.

There is, however, another ground upon which, in their Lordships' opinion, the defendant is entitled to

succeed in this case. It is admitted that the plaintiff company bought with full knowledge of the transactions

with regard to the land occupied by Loke Yew, so that they knew that Haji Mohamed Eusope had parted with

his rights in that land. Under the provisions of s. 3 of Enactment No. 9 of 1903, entitled "An Enactment to

define and amend the Law relating to certain kinds of Specific Relief," the plaintiff company became by the

transfer trustees for Loke Yew in respect of that land. This is clear from Illustration (g) to that section, which

reads as follows:"A. buys certain land with notice that B. has already contracted to buy it. A. is a trustee within the meaning of this

enactment for B. of the land so bought."

The present is an even stronger case, inasmuch as the plaintiff company through Glass, their trustee and

agent in the transaction, were aware that Haji Mohamed Eusope had actually granted away these lands and

been paid for them. The plaintiff company, therefore, are trustees for the defendant for all the rights of which

they thus had notice. These rights amounted to

[1913] A.C. 491 Page 506

the rights of a freeholder subject to an annual payment to the owner of the head grant. Now, it is clear that a

cestui que trust has the right to require a trustee who is a bare trustee for him of land to register that land in

his name, seeing that he is the sole beneficial owner and that the trustee has no interest therein. The present

action from this point of view is an action by a bare trustee of land to eject the beneficial owner who is and

has for years been in possession of the land and is cultivating it.

It is not necessary for their Lordships to decide whether the defence of the Statute of Limitations is well

founded or not, and therefore that question must be taken to be left open.

In the Court of the Judicial Commissioner at Kuala Lumpur, in which the action came on in the first instance,

Braddell J. found in favour of the defendant with costs. On appeal to the Court of Appeal this was set aside.

Page 12

In their Lordships' opinion the appeal ought to have been dismissed. Their Lordships will therefore humbly

advise His Majesty that the judgment of the Court of Appeal should be discharged with costs, and the

judgment of the Court of first instance restored. The respondents must pay the costs of this appeal.

Solicitors for appellant: Gush, Phillips, Walters & Williams.

Solicitors for respondents: Hallowes & Carter.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Rectification RescissionDocumento4 pagineRectification RescissionSyahmi SyahiranNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Borneo V Time EngineeringDocumento24 pagineCase Borneo V Time EngineeringIqram Meon100% (2)

- Dream Property SDN BHD V Atlas Housing SDN BHDDocumento49 pagineDream Property SDN BHD V Atlas Housing SDN BHDHermione Leong Yen KheeNessuna valutazione finora

- Tutorial 12Documento2 pagineTutorial 12Jia Hong0% (1)

- Current Law Journal Reprint Details Singapore Bankruptcy RulingDocumento6 pagineCurrent Law Journal Reprint Details Singapore Bankruptcy RulingIntanSyakieraNessuna valutazione finora

- Presumption of Advancement (Ponniah Case)Documento2 paginePresumption of Advancement (Ponniah Case)IZZAH ZAHIN100% (4)

- Affidavit: By: Norman Zakiyy February 2018Documento42 pagineAffidavit: By: Norman Zakiyy February 2018Fateh NajwanNessuna valutazione finora

- Arif - Letter of Undertaking Maybank To VendorDocumento3 pagineArif - Letter of Undertaking Maybank To VendorDania IsabellaNessuna valutazione finora

- LECTURE Strict Liability RVF 2018Documento21 pagineLECTURE Strict Liability RVF 2018Wendy LimNessuna valutazione finora

- Law of Sucession AssignmentDocumento7 pagineLaw of Sucession Assignmentchan marxNessuna valutazione finora

- Shalini P Shanmugam & Anor V Marni Bte AnyimDocumento7 pagineShalini P Shanmugam & Anor V Marni Bte AnyimAfdhallan syafiqNessuna valutazione finora

- Cases Seri ConnollyDocumento9 pagineCases Seri ConnollyIqram MeonNessuna valutazione finora

- Professional EthicsDocumento36 pagineProfessional EthicsZafry TahirNessuna valutazione finora

- Kabra HoldingsDocumento9 pagineKabra Holdingsnur syazwinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Tutorial 11Documento2 pagineTutorial 11ShereenNessuna valutazione finora

- Prosecution's Appeal Against AcquittalDocumento9 pagineProsecution's Appeal Against AcquittalPrayveen Raj SchwarzeneggerNessuna valutazione finora

- RHB Bank BHD V Travelsight (M) SDN BHD & Ors and Another AppealDocumento25 pagineRHB Bank BHD V Travelsight (M) SDN BHD & Ors and Another AppealhaqimNessuna valutazione finora

- Topic 4 - Constitution of TrustsDocumento10 pagineTopic 4 - Constitution of TrustsAgitha GunasagranNessuna valutazione finora

- Eviction of Unlawful Occupiers of Land in Malaysia - Judicial Responses and PolicyDocumento15 pagineEviction of Unlawful Occupiers of Land in Malaysia - Judicial Responses and PolicyT.r. Ooi100% (1)

- Re Ex Parte Application of Ridzwan Ibrahim (Presumption of Death)Documento16 pagineRe Ex Parte Application of Ridzwan Ibrahim (Presumption of Death)yuuchanNessuna valutazione finora

- Comparison Between MY V NZLDocumento6 pagineComparison Between MY V NZLSerena JamesNessuna valutazione finora

- #6 Alloy Automative SDN BHD V Perusahaan Ironfield SDN BHD (1986) 1 MLJ 382Documento3 pagine#6 Alloy Automative SDN BHD V Perusahaan Ironfield SDN BHD (1986) 1 MLJ 382Fieza ZainulNessuna valutazione finora

- DR Shanmuganathan V Periasamy Sithambaram PillaiDocumento35 pagineDR Shanmuganathan V Periasamy Sithambaram PillaidarwiszaidiNessuna valutazione finora

- Tutorial 1Documento16 pagineTutorial 1Leshana NairNessuna valutazione finora

- Cekal Berjasa SDN BHD V Tenaga Nasional BHD PDFDocumento12 pagineCekal Berjasa SDN BHD V Tenaga Nasional BHD PDFIrdina Zafirah Azahar100% (1)

- T4 - Udl3622 - 1171100151 - Topic 2 - Q3Documento7 pagineT4 - Udl3622 - 1171100151 - Topic 2 - Q3Asho SubramaniNessuna valutazione finora

- FL MaterialsDocumento4 pagineFL MaterialsHermosa ArofNessuna valutazione finora

- EVIDENCE LAW CASE REVIEWDocumento11 pagineEVIDENCE LAW CASE REVIEWbachmozart123Nessuna valutazione finora

- Hyde V WrenchDocumento4 pagineHyde V WrenchMohammad AliNessuna valutazione finora

- Section 90 Indian Evidence ActDocumento11 pagineSection 90 Indian Evidence ActHarita SahadevaNessuna valutazione finora

- Tutorial Case Equitable Assignment & Bare TrustDocumento28 pagineTutorial Case Equitable Assignment & Bare TrustFarhan KamarudinNessuna valutazione finora

- Margaret Chua V Ho Swee Kiew & OrsDocumento6 pagineMargaret Chua V Ho Swee Kiew & OrsArif Zulhilmi Abd Rahman100% (3)

- Malayan Law Journal Reports 1995 Volume 3 CaseDocumento22 pagineMalayan Law Journal Reports 1995 Volume 3 CaseChin Kuen YeiNessuna valutazione finora

- Chan Kok Suan-InjunctionDocumento6 pagineChan Kok Suan-InjunctionUmmi IsmailNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Infra Elite V Pacific TreasureDocumento19 pagineCase Infra Elite V Pacific TreasureIqram MeonNessuna valutazione finora

- ADR - Case ReviewDocumento3 pagineADR - Case ReviewImran ShahNessuna valutazione finora

- 6 Registration & IndefeasibilityDocumento108 pagine6 Registration & IndefeasibilityJayananthini Pushbahnathan100% (1)

- Jual Janji (Malay Customary Land - Malaysian Land Law)Documento2 pagineJual Janji (Malay Customary Land - Malaysian Land Law)月映Nessuna valutazione finora

- 2 MLJ 62, (1997) 2 MLJ 62Documento24 pagine2 MLJ 62, (1997) 2 MLJ 62nuruharaNessuna valutazione finora

- TOPIC 15. Disciplinary ProceedingsDocumento23 pagineTOPIC 15. Disciplinary ProceedingsFatin NabilaNessuna valutazione finora

- 5 and 6 - WritDocumento67 pagine5 and 6 - Writapi-380311750% (2)

- Winding Up and Bankruptcy PDFDocumento21 pagineWinding Up and Bankruptcy PDFSShikoNessuna valutazione finora

- CASE - Araprop V LeongDocumento29 pagineCASE - Araprop V LeongIqram MeonNessuna valutazione finora

- Perfecting Imperfect Gifts and Trusts Have We Reached The End of The Chancellors FootDocumento7 paginePerfecting Imperfect Gifts and Trusts Have We Reached The End of The Chancellors FootCharanqamal SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- Order for Sale Procedures Under National Land CodeDocumento4 pagineOrder for Sale Procedures Under National Land CodeSyafiq Ahmad100% (1)

- Criminal Breach of Trust Case DetailsDocumento5 pagineCriminal Breach of Trust Case DetailsTeam JobbersNessuna valutazione finora

- Compulsory in Malaysia (PT I) : Acquisition of LandDocumento14 pagineCompulsory in Malaysia (PT I) : Acquisition of LandKaren Tan100% (2)

- Cases Student FMDocumento5 pagineCases Student FMkamilNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Talalla V NG Yee FongDocumento8 pagineCase Talalla V NG Yee FongIqram MeonNessuna valutazione finora

- Land Law Case StudyDocumento4 pagineLand Law Case StudyMorgan Phrasaddha Naidu PuspakaranNessuna valutazione finora

- APPALASAMY BODOYAH v. LEE MON SENG (199) 3 CLJ 71Documento15 pagineAPPALASAMY BODOYAH v. LEE MON SENG (199) 3 CLJ 71merNessuna valutazione finora

- Aircraft Documentation OrderDocumento4 pagineAircraft Documentation OrderFaith webbNessuna valutazione finora

- Section 6 - Powers of Attorney Act 1949Documento5 pagineSection 6 - Powers of Attorney Act 1949Zairus Effendi Suhaimi100% (1)

- 2020 TOPIC 3 - Authority of Advocates Solicitors 11 MarchDocumento24 pagine2020 TOPIC 3 - Authority of Advocates Solicitors 11 Marchمحمد خيرالدينNessuna valutazione finora

- Fabulous Range SDN BHD V. Helena K GnanamuthuDocumento19 pagineFabulous Range SDN BHD V. Helena K GnanamuthuAgrey EvanceNessuna valutazione finora

- Section 90A Evidence Act 1950 of Malaysia: A Time For ReviewDocumento11 pagineSection 90A Evidence Act 1950 of Malaysia: A Time For ReviewJoanne LauNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 2 ACCEPTANCEDocumento67 pagineChapter 2 ACCEPTANCER JonNessuna valutazione finora

- Improving Malaysia's Land Registration SystemDocumento48 pagineImproving Malaysia's Land Registration SystemWeihan KhorNessuna valutazione finora

- Nkojo Amooti V Kyazze 2 Ors (Civil Suit No 536 of 2012) 2013 UGHCLD 85 (26 November 2013)Documento6 pagineNkojo Amooti V Kyazze 2 Ors (Civil Suit No 536 of 2012) 2013 UGHCLD 85 (26 November 2013)Fortune RaymondNessuna valutazione finora

- Supreme Court: Toto The Decision of The Regional Trial Court, Branch 04, TuguegaraoDocumento7 pagineSupreme Court: Toto The Decision of The Regional Trial Court, Branch 04, Tuguegaraoroy rubaNessuna valutazione finora

- PP Presentation Q 15 ADocumento8 paginePP Presentation Q 15 ARita LakhsmiNessuna valutazione finora

- Tort NotesDocumento94 pagineTort NotesRita LakhsmiNessuna valutazione finora

- Draft of PleadingsDocumento36 pagineDraft of PleadingsRita LakhsmiNessuna valutazione finora

- Summon Proceeding & Transfer Vs Transmission of CaseDocumento4 pagineSummon Proceeding & Transfer Vs Transmission of CaseRita LakhsmiNessuna valutazione finora

- OCBC Bank Appeals Land CaseDocumento15 pagineOCBC Bank Appeals Land CaseRita LakhsmiNessuna valutazione finora

- Boonsom Boonyanit V Adorna Properties SDN BHDocumento10 pagineBoonsom Boonyanit V Adorna Properties SDN BHRita LakhsmiNessuna valutazione finora

- Role of MSWG in Safeguarding The Interest of Minority Shareholders Interests of in Public Companies in MalaysiaDocumento3 pagineRole of MSWG in Safeguarding The Interest of Minority Shareholders Interests of in Public Companies in MalaysiaRita Lakhsmi100% (2)

- (D) FC - Kheng Soon Finance BHD V MK Retnam HoldingsDocumento9 pagine(D) FC - Kheng Soon Finance BHD V MK Retnam HoldingsRita LakhsmiNessuna valutazione finora

- Act 646 - Arbitration Act 2005Documento44 pagineAct 646 - Arbitration Act 2005Rita LakhsmiNessuna valutazione finora

- Deontological TheoryDocumento2 pagineDeontological TheoryRita LakhsmiNessuna valutazione finora

- Incompatibility of Reservations in Context of Human RightsDocumento2 pagineIncompatibility of Reservations in Context of Human RightsRita LakhsmiNessuna valutazione finora

- Three CertaintiesDocumento7 pagineThree CertaintieslakhsmiNessuna valutazione finora

- Alternative Dispute Resolution in SingaporeDocumento3 pagineAlternative Dispute Resolution in SingaporeRita LakhsmiNessuna valutazione finora

- DLR (4th)Documento2 pagineDLR (4th)Rita LakhsmiNessuna valutazione finora

- Deontological TheoryDocumento2 pagineDeontological TheoryRita LakhsmiNessuna valutazione finora

- DLR (4th)Documento2 pagineDLR (4th)Rita LakhsmiNessuna valutazione finora

- The Rule of LawDocumento1 paginaThe Rule of LawRita LakhsmiNessuna valutazione finora

- The Banking and Financial Institutions Act 1989Documento4 pagineThe Banking and Financial Institutions Act 1989Rita LakhsmiNessuna valutazione finora

- The Banking and Financial Institutions Act 1989Documento4 pagineThe Banking and Financial Institutions Act 1989Rita LakhsmiNessuna valutazione finora

- Republic of The Philippines Supreme Court Manila Second DivisionDocumento7 pagineRepublic of The Philippines Supreme Court Manila Second DivisionIssa Dizon AndayaNessuna valutazione finora

- Iglesia Evangelica Metodista en Las Islas Filipinas, Inc. v. JuaneDocumento8 pagineIglesia Evangelica Metodista en Las Islas Filipinas, Inc. v. JuaneLiz KawiNessuna valutazione finora

- In The United States Bankruptcy Court Eastern District of Michigan Southern DivisionDocumento19 pagineIn The United States Bankruptcy Court Eastern District of Michigan Southern DivisionChapter 11 DocketsNessuna valutazione finora

- Civ-Pro Notes (Gubat)Documento2 pagineCiv-Pro Notes (Gubat)amsanroNessuna valutazione finora

- Rudolph Stanko v. Barack Obama, 3rd Cir. (2010)Documento6 pagineRudolph Stanko v. Barack Obama, 3rd Cir. (2010)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Wachs Amended Complaint - FinalDocumento132 pagineWachs Amended Complaint - FinalEllenBeth WachsNessuna valutazione finora

- Resident Mammal Review NotesDocumento15 pagineResident Mammal Review NotesSu Kings AbetoNessuna valutazione finora

- Gibbs EtcDocumento19 pagineGibbs EtcM Azeneth JJNessuna valutazione finora

- Ophelia Ray Turner v. Childrens Hosp Phila, 3rd Cir. (2010)Documento4 pagineOphelia Ray Turner v. Childrens Hosp Phila, 3rd Cir. (2010)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Taco Bell LawsuitDocumento18 pagineTaco Bell LawsuitKBTXNessuna valutazione finora

- De Leon vs. SalvadorDocumento15 pagineDe Leon vs. SalvadorMiakaNessuna valutazione finora

- Lawsuit Filed Against Norfolk Southern by Morgan & MorganDocumento31 pagineLawsuit Filed Against Norfolk Southern by Morgan & MorganWews WebStaffNessuna valutazione finora

- First Refusal CasesDocumento6 pagineFirst Refusal CasesAriel Mark PilotinNessuna valutazione finora

- CD Asia - Ruiz V Secretary of National Defense GR No. L-15526Documento5 pagineCD Asia - Ruiz V Secretary of National Defense GR No. L-15526Therese ElleNessuna valutazione finora

- Economic Crimes in The PhilippinesDocumento20 pagineEconomic Crimes in The PhilippinesSherwin Anoba Cabutija0% (2)

- Anunciacion V BocanergaDocumento3 pagineAnunciacion V BocanergaEmi SicatNessuna valutazione finora

- Brian Jones - Sandusky RegisterDocumento2 pagineBrian Jones - Sandusky RegisterMike DeWineNessuna valutazione finora

- Home Insurance V Eastern Shipping LinesDocumento2 pagineHome Insurance V Eastern Shipping LinesClar Napa100% (1)

- July Cecil V Hall Kirk (Holiday With Pay Case)Documento10 pagineJuly Cecil V Hall Kirk (Holiday With Pay Case)Carla-anne Harris RoperNessuna valutazione finora

- Lauren Gotthelf v. Boulder, Et Al.Documento23 pagineLauren Gotthelf v. Boulder, Et Al.Michael_Roberts2019Nessuna valutazione finora

- Plaint and WSDocumento4 paginePlaint and WSYusuf KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Vay V Allegheny CountyDocumento7 pagineVay V Allegheny CountyAllegheny JOB Watch100% (1)

- CS Executive Old Syllabus ABC AnalysisDocumento15 pagineCS Executive Old Syllabus ABC Analysisjanardhan CA,CSNessuna valutazione finora

- Lawyer Representation in Court ResearchDocumento6 pagineLawyer Representation in Court Researchanistasnim25Nessuna valutazione finora

- Court Rules on Deficiency Judgment CaseDocumento7 pagineCourt Rules on Deficiency Judgment CaseJoel G. AyonNessuna valutazione finora

- REM - Consolidated Case Digests 2014-June 2016 PDFDocumento1.553 pagineREM - Consolidated Case Digests 2014-June 2016 PDFBaymaxNessuna valutazione finora

- Keller Vs COB MarketingDocumento9 pagineKeller Vs COB MarketingQuennie Jane SaplagioNessuna valutazione finora

- Suit for Declaration of Legal HeirsDocumento3 pagineSuit for Declaration of Legal Heirssikander zamanNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 - Mendoza v. TehDocumento1 pagina1 - Mendoza v. TehTrek Alojado100% (1)

- SAMMANA v. TanDocumento2 pagineSAMMANA v. TanSGOD HRDNessuna valutazione finora