Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Oblicon Case Digests Midterms

Caricato da

denelizaCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Oblicon Case Digests Midterms

Caricato da

denelizaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

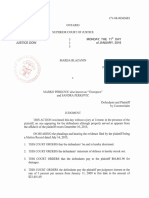

l\.

cpuhlic of tbc

~uprcmc

~bilippinc!1

([ourt

;!Manila

THIRD DIVISION

SPOUSES DEO AGNER and

MARICON AGNER,

Petitioners,

-versus-

G.R. No. 182963

Present:

VELASCO, JR., J, Chairperson,

PERALTA,

ABAD,

MENDOZA, and

LEONEN,JJ.

BPI FAMILY SAVINGS BANK,

Promulgated:

INC.,

.

Respondent.

JUN 0 3 20~ ~

x---------------------------------------------------------------------------(L~----IC---x

DECISION

PERALTA, J.:

This is a petition for review on certiorari assailing the April 30, 2007

Decision 1 and May 19, 2008 Resolution2 of the Court of Appeals in CAG.R. CV No. 86021, which affirmed the August 11, 2005 Decision3 of the

Regional Trial Court, Branch 33, Manila City.

On February 15, 2001, petitioners spouses Deo Agner and Maricon

. Agner executed a Promissory Note with Chattel Mortgage in favor of

Citimotors, Inc. The contract provides, among others, that: for receiving the

111

amount of Php834, 768.00, petitioners shall pay Php 17,391.00 every 15 day

of each succeeding month until fully paid; the loan is secured by a 2001

Mitsubishi Adventure Super Sport; and an interest of 6% per month shall be

4

imposed for failure to pay each installment on or before the stated due date.

Penned by Associate Justice Vicente Q. Roxas, with Associate Justices Josefina Guevara-Salonga

and Ramon R. Garcia concurring; rollo, pp. 49-54.

2

!d. at 56.

Records, pp. 149-151.

!d. at 28.

Decision

-2-

G.R. No. 182963

On the same day, Citimotors, Inc. assigned all its rights, title and interests in

the Promissory Note with Chattel Mortgage to ABN AMRO Savings Bank,

Inc. (ABN AMRO), which, on May 31, 2002, likewise assigned the same to

respondent BPI Family Savings Bank, Inc.5

For failure to pay four successive installments from May 15, 2002 to

August 15, 2002, respondent, through counsel, sent to petitioners a demand

letter dated August 29, 2002, declaring the entire obligation as due and

demandable and requiring to pay Php576,664.04, or surrender the mortgaged

vehicle immediately upon receiving the letter.6 As the demand was left

unheeded, respondent filed on October 4, 2002 an action for Replevin and

Damages before the Manila Regional Trial Court (RTC).

A writ of replevin was issued.7 Despite this, the subject vehicle was

not seized.8 Trial on the merits ensued. On August 11, 2005, the Manila

RTC Br. 33 ruled for the respondent and ordered petitioners to jointly and

severally pay the amount of Php576,664.04 plus interest at the rate of 72%

per annum from August 20, 2002 until fully paid, and the costs of suit.

Petitioners appealed the decision to the Court of Appeals (CA), but

the CA affirmed the lower courts decision and, subsequently, denied the

motion for reconsideration; hence, this petition.

Before this Court, petitioners argue that: (1) respondent has no cause

of action, because the Deed of Assignment executed in its favor did not

specifically mention ABN AMROs account receivable from petitioners; (2)

petitioners cannot be considered to have defaulted in payment for lack of

competent proof that they received the demand letter; and (3) respondents

remedy of resorting to both actions of replevin and collection of sum of

money is contrary to the provision of Article 14849 of the Civil Code and the

Elisco Tool Manufacturing Corporation v. Court of Appeals10 ruling.

The contentions are untenable.

Id. at 29, 33-35.

Id. at 36.

7

Id. at 40.

8

TSN, November 23, 2004, p. 15.

9

ART. 1484. In a contract of sale of personal property, the price of which is payable in

installments, the vendor may exercise any of the following remedies:

(1) Exact fulfillment of the obligation, should the vendee fail to pay;

(2) Cancel the sale, should the vendee's failure to pay cover two or more installments;

(3) Foreclose the chattel mortgage on the thing sold, if one has been constituted, should the

vendee's failure to pay cover two or more installments. In this case, he shall have no further action against

the purchaser to recover any unpaid balance of the price. Any agreement to the contrary shall be void.

10

G.R. No. 109966, May 31, 1999, 307 SCRA 731.

6

Decision

-3-

G.R. No. 182963

With respect to the first issue, it would be sufficient to state that the

matter surrounding the Deed of Assignment had already been considered by

the trial court and the CA. Likewise, it is an issue of fact that is not a proper

subject of a petition for review under Rule 45. An issue is factual when the

doubt or difference arises as to the truth or falsehood of alleged facts, or

when the query invites calibration of the whole evidence, considering mainly

the credibility of witnesses, existence and relevancy of specific surrounding

circumstances, their relation to each other and to the whole, and the

probabilities of the situation.11 Time and again, We stress that this Court is

not a trier of facts and generally does not weigh anew evidence which lower

courts have passed upon.

As to the second issue, records bear that both verbal and written

demands were in fact made by respondent prior to the institution of the case

against petitioners.12 Even assuming, for arguments sake, that no demand

letter was sent by respondent, there is really no need for it because

petitioners legally waived the necessity of notice or demand in the

Promissory Note with Chattel Mortgage, which they voluntarily and

knowingly signed in favor of respondents predecessor-in-interest. Said

contract expressly stipulates:

In case of my/our failure to pay when due and payable, any sum

which I/We are obliged to pay under this note and/or any other obligation

which I/We or any of us may now or in the future owe to the holder of this

note or to any other party whether as principal or guarantor x x x then the

entire sum outstanding under this note shall, without prior notice or

demand, immediately become due and payable. (Emphasis and

underscoring supplied)

A provision on waiver of notice or demand has been recognized as

legal and valid in Bank of the Philippine Islands v. Court of Appeals,13

wherein We held:

The Civil Code in Article 1169 provides that one incurs in delay or

is in default from the time the obligor demands the fulfillment of the

obligation from the obligee. However, the law expressly provides that

demand is not necessary under certain circumstances, and one of these

circumstances is when the parties expressly waive demand. Hence, since

the co-signors expressly waived demand in the promissory notes, demand

was unnecessary for them to be in default.14

11

Royal Cargo Corporation v. DFS Sports Unlimited, Inc., G.R. No. 158621, December 10, 2008,

573 SCRA 414, 421.

12

TSN, November 23, 2004, p. 11.

13

523 Phil. 548 (2006).

14

Id. at 560.

Decision

-4-

G.R. No. 182963

Further, the Court even ruled in Navarro v. Escobido15 that prior

demand is not a condition precedent to an action for a writ of replevin, since

there is nothing in Section 2, Rule 60 of the Rules of Court that requires the

applicant to make a demand on the possessor of the property before an

action for a writ of replevin could be filed.

Also, petitioners representation that they have not received a demand

letter is completely inconsequential as the mere act of sending it would

suffice. Again, We look into the Promissory Note with Chattel Mortgage,

which provides:

All correspondence relative to this mortgage, including demand

letters, summonses, subpoenas, or notifications of any judicial or

extrajudicial action shall be sent to the MORTGAGOR at the address

indicated on this promissory note with chattel mortgage or at the address

that may hereafter be given in writing by the MORTGAGOR to the

MORTGAGEE or his/its assignee. The mere act of sending any

correspondence by mail or by personal delivery to the said address

shall be valid and effective notice to the mortgagor for all legal

purposes and the fact that any communication is not actually received

by the MORTGAGOR or that it has been returned unclaimed to the

MORTGAGEE or that no person was found at the address given, or that

the address is fictitious or cannot be located shall not excuse or relieve

the MORTGAGOR from the effects of such notice.16 (Emphasis and

underscoring supplied)

The Court cannot yield to petitioners denial in receiving respondents

demand letter. To note, their postal address evidently remained unchanged

from the time they executed the Promissory Note with Chattel Mortgage up

to time the case was filed against them. Thus, the presumption that a letter

duly directed and mailed was received in the regular course of the mail17

stands in the absence of satisfactory proof to the contrary.

Petitioners cannot find succour from Ting v. Court of Appeals18

simply because it pertained to violation of Batas Pambansa Blg. 22 or the

Bouncing Checks Law. As a higher quantum of proof that is, proof beyond

reasonable doubt is required in view of the criminal nature of the case, We

found insufficient the mere presentation of a copy of the demand letter

allegedly sent through registered mail and its corresponding registry receipt

as proof of receiving the notice of dishonor.

15

16

17

18

G.R. No. 153788, November 27, 2009, 606 SCRA 1, 20-21.

Records, p. 31.

RULES OF COURT, Rule 131, Sec. 3 (v).

398 Phil. 481 (2000).

Decision

-5-

G.R. No. 182963

Perusing over the records, what is clear is that petitioners did not take

advantage of all the opportunities to present their evidence in the

proceedings before the courts below. They miserably failed to produce the

original cash deposit slips proving payment of the monthly amortizations in

question. Not even a photocopy of the alleged proof of payment was

appended to their Answer or shown during the trial. Neither have they

demonstrated any written requests to respondent to furnish them with

official receipts or a statement of account. Worse, petitioners were not able

to make a formal offer of evidence considering that they have not marked

any documentary evidence during the presentation of Deo Agners

testimony.19

Jurisprudence abounds that, in civil cases, one who pleads payment

has the burden of proving it; the burden rests on the defendant to prove

payment, rather than on the plaintiff to prove non-payment.20 When the

creditor is in possession of the document of credit, proof of non-payment is

not needed for it is presumed.21 Respondent's possession of the Promissory

Note with Chattel Mortgage strongly buttresses its claim that the obligation

has not been extinguished. As held in Bank of the Philippine Islands v.

Spouses Royeca:22

x x x The creditor's possession of the evidence of debt is proof that the

debt has not been discharged by payment. A promissory note in the hands

of the creditor is a proof of indebtedness rather than proof of payment. In

an action for replevin by a mortgagee, it is prima facie evidence that the

promissory note has not been paid. Likewise, an uncanceled mortgage in

the possession of the mortgagee gives rise to the presumption that the

mortgage debt is unpaid.23

Indeed, when the existence of a debt is fully established by the

evidence contained in the record, the burden of proving that it has been

extinguished by payment devolves upon the debtor who offers such defense

to the claim of the creditor.24 The debtor has the burden of showing with

legal certainty that the obligation has been discharged by payment.25

19

Records, p. 145.

Royal Cargo Corporation v. DFS Sports Unlimited, Inc., supra note 11, at 422; Bank of the

Philippine Islands v. Spouses Royeca, G.R. No. 176664, July 21, 2008, 559 SCRA 207, 216; Benguet

Corporation v. Department of Environment and Natural Resources-Mines Adjudication Board, G.R. No.

163101, February 13, 2008, 545 SCRA 196, 213; Citibank, N.A. v. Sabeniano, 535 Phil. 384, 419 (2006);

Keppel Bank Philippines, Inc. v. Adao, 510 Phil. 158, 166-167 (2005); and Far East Bank and Trust

Company v. Querimit, 424 Phil. 721, 730-731 (2002).

21

Tai Tong Chuache & Co. v. Insurance Commission, 242 Phil. 104, 112 (1988).

22

Supra note 20.

23

Bank of the Philippine Islands v. Spouses Royeca, id. at 219.

24

Id. at 216; Citibank, N.A. v. Sabeniano, supra note 20; and Coronel v. Capati, 498 Phil. 248, 255

(2005).

25

Royal Cargo Corporation v. DFS Sports Unlimited, Inc., supra note 11, at 422; Bank of the

Philippine Islands v. Spouses Royeca, supra note 20; Benguet Corporation v. Department of Environment

and Natural Resources-Mines Adjudication Board, supra note 20; Citibank, N.A. v. Sabeniano, supra note

20

Decision

-6-

G.R. No. 182963

Lastly, there is no violation of Article 1484 of the Civil Code and the

Courts decision in Elisco Tool Manufacturing Corporation v. Court of

Appeals.26

In Elisco, petitioner's complaint contained the following prayer:

WHEREFORE, plaintiffs [pray] that judgment be rendered as

follows:

ON THE FIRST CAUSE OF ACTION

Ordering defendant Rolando Lantan to pay the plaintiff the sum of

P39,054.86 plus legal interest from the date of demand until the whole

obligation is fully paid;

ON THE SECOND CAUSE OF ACTION

To forthwith issue a Writ of Replevin ordering the seizure of the

motor vehicle more particularly described in paragraph 3 of the

Complaint, from defendant Rolando Lantan and/or defendants Rina

Lantan, John Doe, Susan Doe and other person or persons in whose

possession the said motor vehicle may be found, complete with

accessories and equipment, and direct deliver thereof to plaintiff in

accordance with law, and after due hearing to confirm said seizure and

plaintiff's possession over the same;

ON THE ALTERNATIVE CAUSE OF ACTION

In the event that manual delivery of the subject motor vehicle cannot be

effected for any reason, to render judgment in favor of plaintiff and

against defendant Rolando Lantan ordering the latter to pay the sum of

SIXTY THOUSAND PESOS (P60,000.00) which is the estimated actual

value of the above-described motor vehicle, plus the accrued monthly

rentals thereof with interests at the rate of fourteen percent (14%) per

annum until fully paid;

PRAYER COMMON TO ALL CAUSES OF ACTION

1.

Ordering the defendant Rolando Lantan to pay the plaintiff

an amount equivalent to twenty-five percent (25%) of his outstanding

obligation, for and as attorney's fees;

2.

Ordering defendants to pay the cost or expenses of

collection, repossession, bonding fees and other incidental expenses to be

proved during the trial; and

3.

Ordering defendants to pay the costs of suit.

Plaintiff also prays for such further reliefs as this Honorable Court

may deem just and equitable under the premises.27

20; Coronel v. Capati, supra note 24, at 256; and Far East Bank and Trust Company v. Querimit, supra

note 20.

26

Supra note 10.

27

Elisco Tool Manufacturing Corporation v. Court of Appeals, id. at 735-736.

Decision

-7-

G.R. No. 182963

The Court therein ruled:

The remedies provided for in Art. 1484 are alternative, not

cumulative. The exercise of one bars the exercise of the others. This

limitation applies to contracts purporting to be leases of personal property

with option to buy by virtue of Art. 1485. The condition that the lessor has

deprived the lessee of possession or enjoyment of the thing for the purpose

of applying Art. 1485 was fulfilled in this case by the filing by petitioner

of the complaint for replevin to recover possession of movable property.

By virtue of the writ of seizure issued by the trial court, the deputy sheriff

seized the vehicle on August 6, 1986 and thereby deprived private

respondents of its use. The car was not returned to private respondent until

April 16, 1989, after two (2) years and eight (8) months, upon issuance by

the Court of Appeals of a writ of execution.

Petitioner prayed that private respondents be made to pay the sum

of P39,054.86, the amount that they were supposed to pay as of May 1986,

plus interest at the legal rate. At the same time, it prayed for the issuance

of a writ of replevin or the delivery to it of the motor vehicle "complete

with accessories and equipment." In the event the car could not be

delivered to petitioner, it was prayed that private respondent Rolando

Lantan be made to pay petitioner the amount of P60,000.00, the

"estimated actual value" of the car, "plus accrued monthly rentals thereof

with interests at the rate of fourteen percent (14%) per annum until fully

paid." This prayer of course cannot be granted, even assuming that private

respondents have defaulted in the payment of their obligation. This led the

trial court to say that petitioner wanted to eat its cake and have it too.28

In contrast, respondent in this case prayed:

(a) Before trial, and upon filing and approval of the bond, to

[forthwith] issue a Writ of Replevin ordering the seizure of the motor

vehicle above-described, complete with all its accessories and equipments,

together with the Registration Certificate thereof, and direct the delivery

thereof to plaintiff in accordance with law and after due hearing, to

confirm the said seizure;

(b) Or, in the event that manual delivery of the said motor vehicle

cannot be effected to render judgment in favor of plaintiff and against

defendant(s) ordering them to pay to plaintiff, jointly and severally, the

sum of P576,664.04 plus interest and/or late payment charges thereon at

the rate of 72% per annum from August 20, 2002 until fully paid;

(c) In either case, to order defendant(s) to pay jointly and severally:

(1) the sum of P297,857.54 as attorneys fees,

liquidated damages, bonding fees and other expenses

incurred in the seizure of the said motor vehicle; and

(2) the costs of suit.

28

Id. at 743-744.

Decision

-8-

G.R. No. 182963

Plaintiff further prays for such other relief as this Honorable Court

may deem just and equitable in the premises.29

Compared with Elisco, the vehicle subject matter of this case was

never recovered and delivered to respondent despite the issuance of a writ of

replevin. As there was no seizure that transpired, it cannot be said that

petitioners were deprived of the use and enjoyment of the mortgaged vehicle

or that respondent pursued, commenced or concluded its actual foreclosure.

The trial court, therefore, rightfully granted the alternative prayer for sum of

money, which is equivalent to the remedy of [e]xact[ing] fulfillment of the

obligation. Certainly, there is no double recovery or unjust enrichment30 to

speak of.

All the foregoing notwithstanding, We are of the opinion that the

interest of 6% per month should be equitably reduced to one percent (1%)

per month or twelve percent (12%) per annum, to be reckoned from May 16,

2002 until full payment and with the remaining outstanding balance of their

car loan as of May 15, 2002 as the base amount.

Settled is the principle which this Court has affirmed in a number of

cases that stipulated interest rates of three percent (3%) per month and

higher are excessive, iniquitous, unconscionable, and exorbitant.31 While

Central Bank Circular No. 905-82, which took effect on January 1, 1983,

effectively removed the ceiling on interest rates for both secured and

unsecured loans, regardless of maturity, nothing in the said circular could

possibly be read as granting carte blanche authority to lenders to raise

interest rates to levels which would either enslave their borrowers or lead to

a hemorrhaging of their assets.32 Since the stipulation on the interest rate is

void for being contrary to morals, if not against the law, it is as if there was

no express contract on said interest rate; thus, the interest rate may be

reduced as reason and equity demand.33

29

Records, pp. 24-25.

In Cabrera v. Ameco Contractors Rental, Inc. (G.R. No. 201560, June 20, 2012 Second Division

Minute Resolution), We held:

The principle of unjust enrichment is provided under Article 22 of the Civil Code which provides:

Article 22. Every person who through an act of performance by another, or any

other means, acquires or comes into possession of something at the expense of the latter

without just or legal ground, shall return the same to him.

There is unjust enrichment "when a person unjustly retains a benefit to the loss of another, or

when a person retains money or property of another against the fundamental principles of justice, equity

and good conscience. The principle of unjust enrichment requires two conditions: (1) that a person is

benefited without a valid basis or justification, and (2) that such benefit is derived at the expense of

another.

31

Arthur F. Menchavez v. Marlyn M. Bermudez, G.R. No. 185368, October 11, 2012.

32

Macalinao v. Bank of the Philippine Islands, G.R. No. 175490, September 17, 2009, 600 SCRA

67, 77, citing Chua v. Timan, G.R. No. 170452, August 13, 2008, 562 SCRA 146, 149-150.

33

Arthur F. Menchavez v. Marlyn M. Bermudez, G.R. No. 185368, October 11, 2012, citing

Macalinao v. Bank of the Philippine Islands, supra, at 77, and Chua v. Timan, supra, at 150.

30

Decision

G.R. No. 182963

- 9-

WHEREFORE, the petition is DENIED and the Court AFFIRMS

WITH MODIFICATION the April 30, 2007 Decision and May 19, 2008

Resolution of the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R. CV No. 86021. Petitioners

spouses Deo Agner and Maricon Agner are ORDERED to pay, jointly and

severally, respondent BPI Family Savings Bank, Inc. ( 1) the remaining

outstanding balance of their auto loan obligation as of May 15, 2002 with

interest at one percent ( 1o/o) per month from May 16, 2002 until fully paid;

and (2) costs of suit.

SO ORDERED.

WE CONCUR:

PRESBITERO J. VELASCO, JR.

ROB~BAD

JOSE

Associate Justice

//

_.c'"""'"'"''~~..;_r'f'"~..-c....,....c;....~

Associate Justice

CA~NDOZA

As~~:J::~ce

Decision

- 10-

G.R. No. I 82963

ATTESTATION

I attest that the conclusions in the above Decision had been reached in

consultation before the case was assigned to the writer of the opinion of the

Court's Division.

PRESBITERO . VELASCO, JR.

Asso mte Justice

Chairper n, Third Division

CERTIFICATION

Pursuant to Section 13, Article VIII of the Constitution and the

Division Chairperson's Attestation, I certify that the conclusions in the

above Decision had been reached in consultation before the case was

assigned to the writer of the opinion of the Court's Division.

MARIA LOURDES P. A. SERENO

Chief Justice

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- 113 - Tano+v.+Socrates 2Documento5 pagine113 - Tano+v.+Socrates 2denelizaNessuna valutazione finora

- AdminDocumento1 paginaAdmindenelizaNessuna valutazione finora

- Regina PDocumento15 pagineRegina PdenelizaNessuna valutazione finora

- 205033Documento13 pagine205033kojie017029Nessuna valutazione finora

- Void AbleDocumento18 pagineVoid AbledenelizaNessuna valutazione finora

- Natres Class Discussions SY 2015-2016: The Regalian Doctrine and Related Concepts in The 1987 ConstiDocumento15 pagineNatres Class Discussions SY 2015-2016: The Regalian Doctrine and Related Concepts in The 1987 ConstidenelizaNessuna valutazione finora

- SSS Law FinalDocumento20 pagineSSS Law FinaldenelizaNessuna valutazione finora

- Blue Book Read and ShareDocumento65 pagineBlue Book Read and SharedenelizaNessuna valutazione finora

- Natres Class Discussions SY 2015-2016: The Regalian Doctrine and Related Concepts in The 1987 ConstiDocumento8 pagineNatres Class Discussions SY 2015-2016: The Regalian Doctrine and Related Concepts in The 1987 ConstidenelizaNessuna valutazione finora

- Joselito C. Borromeo v. Juan T. Mina G.R. No. 193747Documento2 pagineJoselito C. Borromeo v. Juan T. Mina G.R. No. 193747Jaypee Ortiz100% (2)

- 7 DaymentaldietgiftebookDocumento68 pagine7 DaymentaldietgiftebookAdRian CiobanuNessuna valutazione finora

- Elden Claire ADocumento1 paginaElden Claire AdenelizaNessuna valutazione finora

- Prayer For Every NeedDocumento11 paginePrayer For Every NeedJeanette Perez100% (6)

- Rosencor VDocumento117 pagineRosencor VdenelizaNessuna valutazione finora

- Tomimbang V 2Documento10 pagineTomimbang V 2denelizaNessuna valutazione finora

- 3rd MeetingDocumento4 pagine3rd MeetingdenelizaNessuna valutazione finora

- Persons Take 2Documento25 paginePersons Take 2denelizaNessuna valutazione finora

- Elden Claire ADocumento1 paginaElden Claire AdenelizaNessuna valutazione finora

- Sss Benefits I. Sickness Benefits: For Unemployed, Self-Employed and Voluntary MembersDocumento23 pagineSss Benefits I. Sickness Benefits: For Unemployed, Self-Employed and Voluntary MembersdenelizaNessuna valutazione finora

- BALUYOT VDocumento22 pagineBALUYOT VdenelizaNessuna valutazione finora

- Ilaw ReportDocumento1 paginaIlaw ReportdenelizaNessuna valutazione finora

- Pros:: Herbert Bautista Is A Filipino Actor and Politician Currently The Mayor of Quezon CityDocumento1 paginaPros:: Herbert Bautista Is A Filipino Actor and Politician Currently The Mayor of Quezon CitydenelizaNessuna valutazione finora

- Golangco V. Pcib Facts: in 1989, William Golangco Construction Corporation (WGCC) and TheDocumento3 pagineGolangco V. Pcib Facts: in 1989, William Golangco Construction Corporation (WGCC) and ThedenelizaNessuna valutazione finora

- Comparison Chart For Guaranty Pledge and Mortgage 2Documento12 pagineComparison Chart For Guaranty Pledge and Mortgage 2denelizaNessuna valutazione finora

- 3rd MeetingDocumento4 pagine3rd MeetingdenelizaNessuna valutazione finora

- Cacayorin V. Afp Mutual Benefit Facts:Petitioner Oscar Cacayorin (Oscar) Is A Member of Respondent Armed Forces and Police MutualDocumento7 pagineCacayorin V. Afp Mutual Benefit Facts:Petitioner Oscar Cacayorin (Oscar) Is A Member of Respondent Armed Forces and Police MutualdenelizaNessuna valutazione finora

- First United Constructors VDocumento17 pagineFirst United Constructors VdenelizaNessuna valutazione finora

- Southeastern College Vs CADocumento6 pagineSoutheastern College Vs CAdenelizaNessuna valutazione finora

- Philippine National Construction VDocumento22 paginePhilippine National Construction VdenelizaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- 86 People v. BaharanDocumento2 pagine86 People v. BaharanNinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Judgment of Justice DowDocumento3 pagineJudgment of Justice DowIndex.hrNessuna valutazione finora

- Cadayona V CA GR128772Documento4 pagineCadayona V CA GR128772comixsterNessuna valutazione finora

- Almonte V Vasquez 244SCRADocumento2 pagineAlmonte V Vasquez 244SCRAkamil malonzoNessuna valutazione finora

- 2013 SUN-U Completion Withdrawal Form (05022013)Documento2 pagine2013 SUN-U Completion Withdrawal Form (05022013)Chozo TheQhaiNessuna valutazione finora

- Meetup Jane Doe Declaratory JudgmentDocumento7 pagineMeetup Jane Doe Declaratory JudgmentdointhisrightNessuna valutazione finora

- 6 CIR Vs YusecoDocumento6 pagine6 CIR Vs YusecoMary Louise R. ConcepcionNessuna valutazione finora

- Non-Argument Calendar. United States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitDocumento7 pagineNon-Argument Calendar. United States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitScribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Mayors PermitDocumento4 pagineMayors Permitbelly08Nessuna valutazione finora

- Arigo V SwiftDocumento7 pagineArigo V SwiftIAN ANGELO BUTASLACNessuna valutazione finora

- Accretive Health's Motion To Dismiss Complaint Filed by Minnesota Attorney GeneralDocumento6 pagineAccretive Health's Motion To Dismiss Complaint Filed by Minnesota Attorney GeneralMatthew KeysNessuna valutazione finora

- Valdez v. TuasonDocumento2 pagineValdez v. TuasonMichael LazaroNessuna valutazione finora

- BOARD OF MEDICINCE ET AL. v. YASUYUKI OTA GR NO. 166097, July 14, 2008Documento10 pagineBOARD OF MEDICINCE ET AL. v. YASUYUKI OTA GR NO. 166097, July 14, 2008Gela Bea BarriosNessuna valutazione finora

- Ra 349Documento1 paginaRa 349camz_hernandezNessuna valutazione finora

- 10 Eastern Assurance v. Sec of LaborDocumento8 pagine10 Eastern Assurance v. Sec of LaborJoem MendozaNessuna valutazione finora

- Dacumos Vs SandiganbayanDocumento1 paginaDacumos Vs SandiganbayanDanny Dayan100% (1)

- Yu Chuck v. Kong Li PoDocumento2 pagineYu Chuck v. Kong Li PoAbegail Galedo100% (1)

- Guingona vs. GonzalesDocumento3 pagineGuingona vs. GonzalesBeatrice AbanNessuna valutazione finora

- Marie Cris VillarinDocumento1 paginaMarie Cris VillarinFred Nazareno CerezoNessuna valutazione finora

- Cross Examination Questions EditedDocumento7 pagineCross Examination Questions EditedKarl Estacion IV100% (9)

- Two Days International Seminar On Challenges and Prospects of ADR On 14 & 15 June, 2019 at The Indian Law Institute, New DelhiDocumento5 pagineTwo Days International Seminar On Challenges and Prospects of ADR On 14 & 15 June, 2019 at The Indian Law Institute, New Delhibhargavi mishraNessuna valutazione finora

- Notes On ChargeDocumento11 pagineNotes On ChargeKhalid KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Oosbm2015 019Documento3 pagineOosbm2015 019KC SoNessuna valutazione finora

- Senior Certified Litigation Paralegal in San Diego CA Resume Grant GardnerDocumento2 pagineSenior Certified Litigation Paralegal in San Diego CA Resume Grant GardnerGrantGardnerNessuna valutazione finora

- 2 Foodsphere Inc V MauricioDocumento15 pagine2 Foodsphere Inc V MauricioJoanne CamacamNessuna valutazione finora

- Bar Tips: By: Ivanne D'Laureil I. HisolerDocumento17 pagineBar Tips: By: Ivanne D'Laureil I. HisolerApple Ke-eNessuna valutazione finora

- Damaso Serrano Mini Lic Press Release DOJDocumento3 pagineDamaso Serrano Mini Lic Press Release DOJChivis MartinezNessuna valutazione finora

- Garces v. EstenzoDocumento3 pagineGarces v. EstenzoJohney Doe100% (1)

- Thornton Plea AgreementDocumento19 pagineThornton Plea AgreementThe Press-Enterprise / pressenterprise.comNessuna valutazione finora

- Presidential Decree No. 1612: Anti-Fencing Law of 1979Documento37 paginePresidential Decree No. 1612: Anti-Fencing Law of 1979glaiNessuna valutazione finora