Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Controlled Studies of Disorders Treatment And: An Overview of Anxiety in Children Adolescents

Caricato da

Alexandra YoelitaDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Controlled Studies of Disorders Treatment And: An Overview of Anxiety in Children Adolescents

Caricato da

Alexandra YoelitaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

An Overview of Controlled Studies of Anxiety

Disorders Treatment in Children and

Adolescents

Roxanne W. Scott, MD; Kess Mughelli, BA; and Deborah Deas, MD, MPH

Charleston, South Carolina

Objective: Although several treatments for children and

adolescents with anxiety disorders are available, there are

few well-controlled studies in the literature that compare

these treatments for efficacy. The objective of this paper is

to provide an overview of controlled treatment studies for

children and adolescents with anxiety disorders.

Method: The research literature on controlled treatment

studies of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents was

systematically reviewed through a search of PsycINFO and

Medline. Studies that did not compare the efficacy of treatment modalities were excluded.

Results: This review focuses specifically on three main treatment modalities: cognitive-behavioral therapy, both individual and group; family-based interventions; and pharmacotherapy. Each of these modalities is reviewed in the

context of the separate disorders as defined by DSM-111-R

and/or DSM-IV. The results are especially promising for cognitive-behavioral therapy and pharmacotherapy for many

of the anxiety disorders; however, there are concerns about

small sample sizes, lack of descrbed comorbidity within the

groups and generalizability.

Conclusion: While great strides have been made in the

treatment of child and adolescent anxiety disorders, empircally based studies are quantitatively limited. More research

is needed involving head-to-head trials of the different

modalities.

Key words: children/adolescents * anxiety U treatment

2005. From the Medical University of South Carolina (Scott, clinical assistant professor of psychiatry; Mughelli, medical student; Deas, associate

professor of psychiatry) and the Charleston Area Mental Health Center

(Scott, child psychiatrist), Charleston, SC. Send correspondence and

reprint requests for J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97:13-24 to: Deborah Deas,

Department of Psychiatry, Medical University of South Carolina, 67 President St., 460 IOP, Charleston, SC 29425; phone: (843) 792-5214; fax: (843)

792-7353; e-mail: deasd@musc.edu

JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL MEDICAL ASSOCIATION

Anxiety disorders are the most common group of

psychiatric illnesses in children.'-' Kashani and

Orvaschel4 reported prevalence rates of 17.3% for

anxiety disorders in a sample of adolescents. There

are psychosocial and psychopharmacological treatment modalities based on research with sound experimental design; however, there is a paucity of proven

efficacious treatments for children and adolescents.

There are limited data on the psychopharmacological

treatment of anxiety disorders in children, with the

exception of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).s

Over the last several years, more controlled studies

have been conducted to examine the effectiveness of

different treatments for childhood anxiety disorders,

however, few of these include head-to-head trials

comparing interventions between and within different

categories. This review focuses specifically on studies

that compare outcomes ofthese interventions for children and adolescents.

The purpose of this paper is to present an

overview of controlled studies conducted in the past

10 years that compares the standard treatments most

often used in clinical practice to treat children and

adolescents with anxiety disorders. An extensive literature search was conducted using Medline and

Psyclnfo. Articles included were limited to randomized, controlled studies performed in the last decade

focusing on treatment of various anxiety disorders.

The articles included focus on a broad spectrum of

treatment modalities for specific anxiety disorders,

such as OCD, as well as for anxiety disorders in general (mainly generalized anxiety disorder, separation

anxiety disorder and social anxiety disorder). The

three main categories of treatment modalities

include: 1) cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) with

subdivision into individual and group, 2) family

interventions paired with CBT, and 3) pharmacological interventions. This review will provide a general

overview of specific anxiety disorders in children/

adolescents and the controlled studies conducted to

define efficacious treatment. In the literature, generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder

VOL. 97, NO. 1, JANUARY 2005 13

ANXIETY DISORDERS TREATMENT

(social phobia) and separation anxiety disorder were

often combined in the studies, and thus, this review

will maintain that designation. The other anxiety

disorders that have been studied in controlled trials

are OCD, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD),

school phobia and specific phobias.

Separation Anxiety Disorder,

Generalized Anxiety Disorder and

Social Anxiety Disorder

The essential feature of separation anxiety disorder is excessive worry concerning separation from

the home or from those to whom the person is

attached.6 This worry is beyond what is expected for

the individual's developmental level. In clinical samples, the disorder is equally common in males and

females; however, in epidemiological samples the

disorder is more frequent in females.

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is character-

ized by excessive worry about a variety of situations.

In children and adolescents, the worries often concern the quality of performance at school or in sporting events, punctuality or catastrophic events.7 The

diagnosis of overanxious disorder from DSM-IJI-R

was eliminated in DSM-IV and the criteria for GAD

modified for children. Therefore, there is some controversy about the link between overanxious disorder and generalized anxiety disorder in children. In a

study by Kendall and Warman,8 a large group of

children with overanxious disorder met criteria for

generalized anxiety disorder. Therefore, the prevalence rates for the two closely approximate each other. As a result, many of the studies reviewed here

tended to collapse the two groups into one category.

In community epidemiological studies, the prevalence rates for overanxious disorder have ranged

from 2.9% to 4.6%.9

Social anxiety disorder (social phobia) has as its

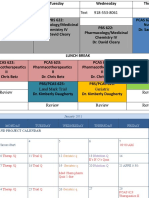

Table 1. Summary of Controlled

Study

Kendall,

1994

Barrett PM

et al., 1996

Treatment Modality

Outcome Measure(s)

Cognitive-behavioral therapy

(n=27) vs. wait-list control (n=20)

(total=47)

The Revised Children's Manifest Anxiety Scales (RCMAS),

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAIC-C), Fear

Survey Schedule for Children-Revised (FSSC-R), Children's

Depression Inventory (CDI), Coping Questionnaire-Child

(CQ-C), Children's Negative Affectivity Self-Statement

Questionnaire (NASSQ), Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL),

Child-Behavior Checklist-Teacher Report Form (TRF)

Cognitive-behavioral therapy

(CBT) (n=28) vs. CBT plus family

anxiety management (CBT+

FAM) (n=25) vs. waiting list (n=26)

RCMAS, FSSC-R, CDI, CBCL, Depression Anxiety Stress

Scales (DASS), Family Enhancement of Avoidant

Responses (FEAR)

(total =79)

Kendall et

al., 1997

CBT (n=60) vs. waiting list (n=34)

(total=94)

RCMAS, STAIC, FSSC-R, CDI, CQ-C, NASSQ, CBCL, STAICModification of trait version for parents (STAIC-A-Trait-P),

Coping Questionnaire-Parent (CQ-P), State Trait Anxiety

Inventory, Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), CBCL-TRF

Silverman

et al., 1999

Group cognitive-behavioral

therapy (GCBT) (n=37) wait-list

control (WLC) (n=19)

(total=56)

Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Children (ADISC) and (ADIS-P), RCMAS, FSSC-R, Child Behavior Checklist

(CBCL), Parent Global Rating of Severity (PGRS)

Mendlowitz

et al., 1999

CBT parent-child condition

(n=18), vs. CBT child-only

condition (n=23) vs. CBT parentonly condition (n=21)

RCMAS, CDI, Children's Coping Strategies Checklist

(CCSC), Global Improvement Scale (CGI)

(total=62)

Shortt et

al., 2001

Family-based cognitive-

RCMAS, CBCL

behavioral treatment (FGCBT)

(n=54) vs. wait-list condition

(n= 17)

(total=71)

14 JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL MEDICAL ASSOCIATION

VOL. 97, NO. 1, JANUARY 2005

ANXIETY DISORDERS TREATMENT

core feature excessive anxiety about social or performance situations in which the individual fears

scrutiny or exposure to unfamiliar persons.8 Onset of

social anxiety most commonly occurs in mid-adolescence. Adolescents with social anxiety disorder

may have few friends, have difficulties with intimate

relationships and/or develop substance abuse. Figures based on DSM-IJI-R criteria placed the prevalence rate at 1%. Kendall and Warman's study found

that 18% of their sample met DSM-III-R criteria for

social phobia, yet 40% of the same sample met

DSM-IV criteria.8 This may indicate an underestimation of the prevalence of social anxiety disorder.

The literature has relatively recently begun to

evolve to include clinical trials of childhood anxiety

disorders. Kendall performed the first randomized

clinical trial investigating the efficacy of a cognitive-behavioral therapy intervention for children

diagnosed with an anxiety disorder (these disorders

did not include specific phobias or OCD).'0 Fortyseven children aged 9-13 years old were randomly

assigned to either cognitive-behavioral therapy

(N=27) or a wait-list condition (N=20). Children in

the CBT condition received 16 weekly sessions that

included helping the child to: 1) recognize anxious

feelings and somatic reactions to anxiety, 2) clarify

cognition in anxiety-provoking situations, 3) develop a plan to help cope with the situation, and 4) evaluate performance and administer self-reinforcement

as appropriate. The wait-list condition was for eight

weeks, at the end of which time those children could

receive the CBT intervention. The results revealed

that the subjects treated with the CBT intervention

made clinically significant gains as measured at the

end of treatment and that these gains were maintained at a one-year follow-up. Kendall's study has

since been followed by a controlled trial by Barrett,

Dadds, and Rapee in Queensland, Australia," and

Studies of Anxiety Disorder Treatment

Findings

The CBT group showed significantly greater improvement compared to the wait-list group. In the CBT

group, 64% of patients no longer met anxiety disorder diagnostic criteria after treatment compared to

5% participants in the wait-list group.

Treatment children (CBT and CBT + FAM) showed significantly greater improvement compared to the wait-list

group. During posttreatment, 69.8% of all the CBT treatment children no longer met anxiety diagnostic criteria

compared to 26% of the wait-list children. The CBT + FAM condition exhibited significant improvements

compared to CBT-only condition. At 12-month follow-up, 95.6% of children in CBT + FAM group no longer met

diagnostic criteria compared to 70.3% CBT-only children.

The CBT treatment group showed significant improvement over time compared to the wait-list group.

Seventy-one percent of the CBT group no longer met their primary diagnosis at the end of treatment. At

posttreatment, 53% of CBT children no longer met their anxiety disorder diagnosis compared to 6% of

wait-list children.

Participants in the GCBT group showed more significant improvement when compared to the wait-list

group. Based on the CBCL scores, 82% of GCBT subjects exhibited significant improvement at

posttreatment, while 9% of the wait-list subjects showed improvement.

Parents of children in the CBT parent-child group evaluated their children as significantly more improved

compared to parent-evaluations of children from the other two groups. Decreases in anxiety and depression

symptoms were reported for all the treatment groups at posttreatment. Children in the parent-child group used

their coping skills more actively than the children in the other two treatment conditions. Overall, in posttreatment,

females reported less anxiety than males.

In posttreatment, significantly more FGCBT children were diagnosis-free compared to wait-list children.

Results from this study show that 69% of participants who finished FGCBT were diagnosis-free, while 6% of

the wait-list children were diagnosis-free.

JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL MEDICAL ASSOCIATION

VOL. 97, NO. 1, JANUARY 2005 15

ANXIETY DISORDERS TREATMENT

another study by Kendall et al. in 1997, again looking at treatment of anxiety disorders in children

using a cognitive-behavioral approach.'2

There is emerging evidence that group CBT is

efficacious in the treatment of childhood anxiety

disorders. Barrett conducted the first study exploring the efficacy of group CBT (GCBT).13 The three

treatment conditions included GCBT, GCBT plus

family management (GCBT + FAM) and wait-list.

At the 12-month follow-up, there was no statistically

significant difference between the GCBT and

GCBT + FAM groups; however, both groups maintained significantly better outcomes than the waitlist condition. Thus, it appeared that GCBT was

effective but that the parental involvement was

equivocal.

In a study by Silverman and colleagues,'4 the primary goal was to evaluate the efficacy of GCBT for

treating anxiety in children. A secondary goal was to

extend and complement the ratings instruments that

had been used in previous studies to measure outcome. Two global ratings of clinical severity were

Table 1. Summary of Controlled

Study

Beidel et

al., 2000

l

__________

Treatment Modality

Social effectiveness therapy for

children (SET-C) group (n=36) vs.

nonspecific treatment control

group (Testbusters) (n=31)

| (total=67)

Outcome Measure(s)

CDI, Eysenck Personality Inventory, Social Phobia and

Anxiety Inventory for Children (SPAI-C), and STAIC-C,

CBCL, Children's Global Assessment Scale (K-GAS)

l

Pediatric

Psychophar

macology

Anxiety

Study

Group, 2001

Fluvoxamine 50-300 mg/day for

eight weeks (n=63) vs. placebo

(n=65)

(total= 128)

Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale, Clinical Global ImpressionsImprovement Scale, Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for

Children, Screen for Child Anxiety-Related Emotional

Disorders

Rynn et al.,

2001

Sertraline 25-50mg for nine

weeks (n=1 1) vs. placebo (n=1 1)

(total=22)

Hamilton Anxiety Scale, Clinical Global Impression (CGI),

Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for children, RCMAS, 17-item

Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

DeVaughGeiss et al.,

1992

Clomipramine hydrochloride

(CMI) 25-200mg for 10 weeks

(n=31) vs. placebo (n=29)

(total=60)

Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS), NIMH

Global Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (NIMH GOCS),

Physician Global Evaluation of Change, Patient SelfRating Scale

March et

al., 1998

Sertraline (25-200mg/day for 12

weeks) (n=92) vs. placebo (n=95)

(total=187)

Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (CYBOCS), NIMH GOCS, NIMH Clinical Global Impressions of

Severity of Illness (CGI-S) and Improvement (CGI-1) rating

scales

Riddle et

al., 1992

Fluoxetine 20 mg for eight weeks

(n=7) vs. placebo (n=6)

(total=1 1)

CY-BOCS, Clinical Global Impression-Obsessive Compulsive

Disorder scale (CGI-OCD), Leyton Obsessional InventoryChild Version (LOI-CV), RCMAS, CDI, K-GAS

Geller et

al., 2001

Fluoxetine 20-60mg for 13 weeks

(n=71) vs. placebo (n=32)

(total= 103)

CY-BOCS, CGI-Severity Scale, CGI-lmprovement Scale,

Patients Global Impressions Scale (PGI), NIMH-GOCS,

Children's Depression Rating Scale-Revised (CDRS-R)

16 JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL MEDICAL ASSOCIATION

VOL. 97, NO. 1, JANUARY 2005

ANXIETY DISORDERS TREATMENT

used as well as three child self-report measures and

three parent-report measures. In addition, frequency

of follow-up intervals was increased to three-, sixand 12 months. Fifty-six children ages 6-16 years

old were randomly assigned to GCBT or wait-list

condition. The results showed that 64% of the children in the GCBT were recovered at posttreatment,

compared to 13% ofthe children in the wait-list condition. Significant treatment gains were also maintained in the GCBT subjects at 12 months.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy, both individual and

group, has been shown to be efficacious when treating childhood anxiety disorders when compared to a

wait-list condition. Several investigators have identified that and are seeking to understand how the

parental component contributes to the improvement

of these children. There is growing evidence that

anxiety in children is significantly related to frequent negative feedback and parental restriction.15

Prior to a 1996 study by Barrett and associates, no

study had yet examined the value of incorporating

parent training in treatment outcome studies in

Studies of Anxiety Disorder Treatment continued

Findings

The SET-C group showed significantly more improvement than the Testbusters group. In posttreatment,

67% of participants in the SET-C group no longer met criteria for social phobia, while only 5% of

participants in Testbusters no longer met criteria. These improvement remained the same for the sixmonth follow-up.

The fluvoxamine group showed significantly greater improvement than the placebo group. On the

Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale, subjects in the fluvoxamine group had a decrease of 9.7 points, while

subjects in the placebo group had a decrease of 3.1 points. Based on the CGI scale, 76% fluvoxamine

subjects responded to treatment vs. 29% placebo subjects.

The results favor a 50-mg dosage of sertraline as being more effective than placebo in treating

generalized anxiety disorder in children. The Hamilton Anxiety Scale showed that sertraline patients had

a decrease of 13.8 points in their anxiety scores from baseline to week nine compared to a 2.3 point

decrease in placebo patients. The CGI severity and improvement scale scores also showed significant

treatment differences in favor of sertraline.

Based on Y-BOCS scores, the CMI group exhibited greater improvement than the placebo group. The CMI

group had a mean reduction of 37% in their Y-BOCS score vs. 8% reduction in the placebo group. The

Physicians Global Scores indicate that 60% of CMI patients received a very-much or much-improved rating

compared to 10-17% placebo subjects. NIMH GOCS scores and Patient Self-Rating Scales were all

consistent with the Y-BOCS results in favor of CMI treatment.

Subjects receiving sertraline exhibited significantly greater improvement overall than did placebo

subjects. In the sertraline group, 53% received a 25% decrease in CY-BOCS score from baseline to end

point, compared to 37% in the placebo group. Additionally, 42% of sertraline subjects received a NIMH

CGI-I rating of very-much-improved or much-improved, compared to 26% in the placebo group.

The subjects in the fluoxetine group showed significant decreases in the severity of obsessive-compulsive

symptoms (CY-BOCS mean decrease=44% and CGI-OCD mean decrease= 33%). The placebo subjects

showed smaller nonsignificant decreases in obsessive compulsive symptom severity (CY-BOCS mean

decrease=27% and CGI-OCD mean decrease=1 2%). On the CGI-OCD, the fluoxetine group showed

significantly greater improvement in scores from baseline to end of treatment when compared to placebo.

This study's results demonstrated that fluoxetine is safe and effective for the short-term treatment of children

and adolescents with OCD.

The fluoxetine group showed significantly greater improvement compared to placebo. Based on CYBOCS, 49% fluoxetine subjects were responders to treatment, whereas only 25% placebo subjects

responded to treatment. Fifty-five percent of patients in the fluoxetine group were rated much-improved

or very-much-improved on the CGI scales compared to 18.8% of placebo subjects.

JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL MEDICAL ASSOCIATION

VOL. 97, NO. 1, JANUARY 2005 17

ANXIETY DISORDERS TREATMENT

childhood anxiety. One significance of this study is

its design, which compared two methods of treatment with a control condition. Barrett and colleagues investigated the effectiveness of cognitivebehavioral and family management training

procedures with childhood anxiety disorders. Seventy-nine children aged 7-14 years were randomly

assigned to receive child-only CBT, child CBT plus

family anxiety management training (CBT + FAM)

or a wait-list condition. The family intervention

involved three phases: 1) parenting skills for managing child distress and avoidance, 2) parenting skills

to manage their own anxiety and 3) parental communication and problem-solving skills. The results

of the study were very promising indeed. Both the

CBT and CBT + FAM groups had significantly better outcomes than the wait-list group, and the CBT +

FAM was found to be significantly more efficacious

than the CBT group. Sixty-one percent of the children in the CBT group no longer met DSM-ILI-R

criteria for any anxiety disorder as compared to 88%

of the CBT + FAM group, which no longer met

diagnostic criteria. At the 12-month follow-up, the

difference between the CBT and the CBT + FAM

Table 1. Summary of Controlled

Treatment Modality

Outcome Measure(s)

Riddle et

al., 2001

Fluvoxamine 25-200 mg for 10

weeks (n=57) vs. placebo (n=63)

(total=1 20)

Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale

(CY-BOCS), NIMH GOCS and CGI scales for the clinician,

parent and subject

De Haan E

et al., 1998

Behavioral therapy (BT) (n=12),

vs. clomipramine (n=10) (total

CY-BOCS, LOI-CV, Children's Depression Scale (CDS),

CBCL

Study

=22)

(total=34)

School Attendance, Fear Thermometer (FT), FSSC-R II,

RCMAS, CDI, Self-Efficacy Questionnaire for School

Situations (SEQSS), CBCL, CBCL-TRF, Global Assessment of

Functioning (GAF)

Last et al.,

1998

CBT (n=23) vs. ES (n=21)

(total=44)

School Attendance Record, Global Improvement Scale,

FSSC-R, modified STAIC-C (STAIC-M), CDI, Posttreatment

Diagnosis

Bernstein

et al., 2000

Impramine (25 mg for eight

weeks) plus CBT (n=31) vs.

placebo plus CBT (n=32)

Anxiety Rating for Children-Revised (ARC-C), Children's

Depression Rating Scale-Revised (CDRS-R), RCMAS, BDI,

school attendance

King et

al., 1998

CBT (n= 1 7) vs. wait-list condition

(WLC) (n=1 7)

(total=63)

Cohen et

al., 1996

CBT for sexually abused

preschool children (CBT-SAP)

(n=39) vs. nondirect supportive

therapy (NST) (n=28)

Preschool Symptom Self Report (PRESS), CBCL-Parent

Version, Child Sexual Behavior Inventory (CSBI), Weekly

Behavior Record (WBR)

(total=67)

King et al.,

2000

Child-alone CBT (n=12) vs. Family

cognitive therapy CBT (n=12)

vs. wait-List condition (n= 1 2)

(total=36)

Silverman

et al., 1999

Contingency management

treatment condition (CM) (n=40)

vs. cognitive self-control

condition (SC) (n=41) vs. ES

FT for sexually abused children, Coping Questionnaire for

Sexually Abused Children, RCMAS, CDI, CBCL, GAF

RCMAS, FSSC-R, FT, CDI, Children's Negative Cognitive

Error Questionnaire (CNCEQ), CBCL, Parent Global

Rating of Severity (PGRS)

(n=23)

(total= 104)

18 JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL MEDICAL ASSOCIATION

VOL. 97, NO. 1, JANUARY 2005

ANXIETY DISORDERS TREATMENT

groups remained significant. Fifty-two of the participants from the original study participated in a sixyear follow-up to examine not only if the treatment

gains were still present within the two groups but

also whether the CBT + FAM group still had relative

superiority to the CBT-only group. The results

showed that 87% of the children no longer met diagnostic criteria for an anxiety disorder and that both

treatments were equally effective.

Mendlowitz and colleagues also examined the

role of parental involvement coupled with group

cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of

childhood anxiety disorders.'6 Sixty-two children

were randomly assigned to one of three 12-week

treatment conditions: 1) parent and child intervention, 2) child-only intervention and 3) parent-only

intervention. All treatment groups experienced a

reduction in both anxiety and depressive symptoms,

suggesting that group CBT is efficacious in treating

children with anxiety disorders. It was also noted

that parental involvement uniquely contributed to

improved coping strategies in the parent-child condition. In this study, there was no 12-month followup posttreatment.

Studies of Anxiety Disorder Treatment continued

Findings

Fluvoxamine subjects showed significantly greater improvement compared to placebo subjects. Based

on CY-BOCS scores, 42% of the fluvoxamine group showed improvement compared to 26% of those

taking placebo.

Both treatment studies showed significant improvement. CY-BOCS obsessive compulsive scores

decreased from 21.5 to 9.1 for the BT group, compared to a 23.8-to-I 7.6 decrease in the clomipramine

group. Based on the CY-BOCS data, behavioral therapy resulted in stronger therapeutic changes

compared to clomipramine. However, the LOI-CV data showed that there were no significant

differences between the two treatments.

CBT children showed significant school attendance improvement when compared to the wait-list

children. CBT children went from being present 61.47% of school days at pretreatment to 93.53% of the

days at posttreatment. The WLC children increased attendance from 40% days present at pretreatment

to 56% days present at posttreatment. CBT children also showed more improvement than WLC children

in the self-report measures and in the clinician's GAF.

Overall, the measures showed no significant differences between the two treatment groups. The two

treatments were found to be equally effective at decreasing children's anxiety and depressive symptoms.

In posttreatment, 65% from the CBT group and 50% of the ES group no longer met diagnostic criteria.

The impramine plus CBT group significantly improved their school attendance over the course of

treatment, whereas the placebo plus CBT group showed no significant improvement in school

attendance. The impramine group went from a mean attendance rate of 28% at baseline to 70% at

week eight. The placebo group increased attendance rate from 17% at baseline to 36% on week eight.

The CBT-SAP group displayed more symptomatic improvement on most of the outcome measures when

compared to the NST group. On the CBCL-Total Behavior Problems Scale, 56% of the CBT-SAP subjects

showed clinical improvement compared to 22% of the NST subjects. For the CBCL-Internalizing scale, 60%

of CBT-SAP improved vs. 1 % of the NST subjects. On the CBCL-Externalizing Scale, 64% of CBT-SAP

improved vs. 12% from the NST group.

Children from the treatment groups (child CBT and family CBT) exhibited more improvement than wait-list

children. However, the analysis of covariance data did not reveal any significant difference between

child-CBT and family-CBT treatment results.

Children from all three treatment groups showed equally significant improvement on all outcome

measures. There was no consistent pattern of differences. Clinically significant improvement was defined

as having a less-than-70 total score on the CBCL Anxious/Depressed Subscale. Based on CBCL scores,

67% from the SC group, 56% from the CM group and 75% from the ES group showed clinically significant

improvement at posttreatment.

JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL MEDICAL ASSOCIATION

VOL. 97, NO. 1, JANUARY 2005 19

ANXIETY DISORDERS TREATMENT

Shortt and colleagues conducted the first randomized clinical trial evaluating the efficacy of the

FRIENDS program, a family-based group cognitivebehavioral treatment (FGCBT) for anxious children.'7

FRIENDS is an acronym for the strategies taught in

the sessions (F-Feeling worried?; R-Relax and

feel good; I-Inner thoughts; E-Explore plans; NNice work so reward yourself; D-Don't forget to

practice; and S-Stay calm, you know how to cope

now). FRIENDS has a number of unique features,

including two forms for children ages 6-1 1 years and

ages 12-16 years. Also, it incorporates a family skills

component involving cognitive restructuring for parents and assisting families in building social support.

Seventy-one children ranging in age from 6-10 years

who met diagnostic criteria for separation anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder or social anxiety

disorder were randomly assigned to the FRIENDS

group or a wait-list control. Children in the treatment

group participated in 10 weekly sessions in addition

to two booster sessions that occurred one- and three

months following completion of treatment. The

results indicated that children who completed the

FRIENDS program showed greater improvement

than the wait-list condition. Sixty-nine percent of

children who completed the FGCBT were diagnosisfree, as compared to 6% ofthe children in the wait-list

condition. At 12-month follow-up, 68% of the children in the treatment group were diagnosis-free.

Beidel and colleagues conducted a study evaluating the efficacy of Social Effectiveness Therapy for

Children (SET-C) a structured behavioral therapy.'8

The therapy consisted of 24 sessions with 12 group

sessions and 12 individual exposure sessions. Sixtyseven children aged 8-12 years were randomly

assigned to either the SET-C group or an active, nonspecific intervention (Testbusters). Testbusters is a

program that includes study skills and test-taking

strategies but does not specifically address social

anxiety. Fifty children completed the study. Those in

the SET-C group showed significant improvement in

functioning and decrease in symptoms. Sixty-seven

percent ofthe SET-C group no longer met diagnostic

criteria for social phobia compared to 5% ofthe control group. Treatment gains were maintained at sixmonth follow-up.

Few controlled studies exist that examine the

pharmacological treatment of childhood anxiety disorders. The Research Unit on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Anxiety Study Group'9 conducted a randomized, double-blind trial of fluvoxamine and

placebo in children with social phobia, separation

anxiety disorder or generalized anxiety disorder. The

study included 128 children aged 6-17 years. All

children received supportive psychotherapy during

the eight-week study period. Significant differences

20 JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL MEDICAL ASSOCIATION

between the treatment groups were detected as early

as week three and increased through week six, at

which time they plateaued. In a second study, Rynn

and colleagues conducted the first randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of a selective

serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI)-sertraline-in

children and adolescents with a primary diagnosis of

generalized anxiety disorder.20 Twenty-two children

and adolescents aged 5-17 years were assigned to

either the sertraline or placebo group for a nineweek study. Psychotherapy except for cognitivebehavioral therapy was allowed, provided the

patients had been receiving the same therapy for the

three months prior to the study and that the level of

intensity remained unchanged throughout the study.

The results of this study suggest that sertraline at a

low dose of 50 mg daily is safe and efficacious in

treating generalized anxiety disorder in children.

There were no significant differences between the

groups with respect to adverse events.

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder

OCD is a disorder of early onset characterized by

recurrent obsessions or compulsions severe enough to

be time-consuming or result in marked distress or significant impairment.6 Obsessions are defined as

recurrent and persistent thoughts, images or impulses

that are egodystonic and intrusive. Compulsions serve

to alleviate dysphoric affects associated with obsessions. Costello et al.2' reported a prevalence of less

than 1% in prepubertal children. Lifetime prevalence

rates for adolescents range from 1.9% to 3.6%.2224

OCD has received much attention from investigators seeking efficacious pharmacological therapy for

children and adolescents. There is much more in the

literature examining the use of SSRI's in the treatment

of OCD than of any other anxiety disorder in children; however, there are few double-blind, controlled

studies. In one study, DeVeaugh-Geiss and

colleagues25 found that 60% of patients that received

clomipramine treatment showed significant improvement. In a study completed by March et al,5 sertraline

was found to be effective for treatment of pediatric

OCD. Riddle et al. found that fluoxetine was significantly better than placebo on major outcome variables

and was generally well-tolerated.26 Geller and colleagues also conducted a study to determine the efficacy of fluoxetine in the treatment of pediatric OCD.27

Fluoxetine was found to be significantly more effective than placebo as evidenced by greater reductions

in Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive

Scale (CY-BOCS) scores. Riddle and colleagues also

conducted a 10-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial examining the efficacy of fluvoxamine.28 The results indicate that the

decrease in symptom severity was significant when

VOL. 97, NO. 1, JANUARY 2005

ANXIETY DISORDERS TREATMENT

compared with placebo and was comparable to the

rates of response in other studies. Children were

found to have a higher rate of response than adolescents in this particular study. Both sertraline and fluvoxamine have been approved for the treatment of

OCD in children and adolescents. The tricyclic drug

clomipramine has also been approved for treatment of

OCD but is considered a second-line agent due to its

side-effect profile.29

De Haan and colleagues conducted the first study

comparing a psychosocial treatment to drug treatment

for OCD in children.30 Twenty-two children aged

8-18 years were assigned to one of two groups:

behavior therapy or clomipramine therapy. The

behavior therapy consisted of 12 weekly sessions

incorporating exposure and response prevention. The

drug therapy group also met weekly. Initial dose of

clomipramine was 25 mg for the first week and was

titrated to a maximum of 200 mg/day. In the behavior

therapy condition, the mean improvement was 59.9%

as compared to 33.4% in the clomipramine condition.

The results for the behavior therapy condition are

comparable to those from March's study.31 In his

study, the mean improvement was 50%; however,

most of those children received concomitant medication. Improvement in the clomipramine condition was

rather low compared to other studies.

Behavioral treatment for OCD has emerged as

the treatment of choice; however, there is a lack of

rigorous randomized controlled trials examining the

efficacy of CBT versus control or other comparison

treatments. March and colleagues have conducted a

number of open trials and case studies investigating

the use of CBT for children with OCD. Those studies will not be discussed here since the focus of this

paper is to review controlled studies.

School Refusal

School refusal is another disorder with emerging

treatment data in the literature. King and Bernstein32

define school refusal as difficulty attending school

that is associated with emotional distress, especially

anxiety and depression. Separation anxiety and

school phobia have been used interchangeably; however, several studies focus on treatment of school

refusal as its own entity apart from separation anxiety. School refusal affects approximately 5% of all

school-age children.33-35 There is a bimodal peak for

age of onset-5-6 years and 10-1 1 years of age.

There have been two studies that support the efficacy of CBT for school refusal since 1992. In a trial by

King et al,36 34 children ages 5-15 years were randomly assigned to a four-week cognitive-behavioral

intervention which included six individual therapy

sessions evenly distributed across the four-week

treatment period with the child, five with the parents

JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL MEDICAL ASSOCIATION

involving training in behavior management skills

with the goal being school attendance, and one session with the teacher or a wait-list control condition.

The results indicated that CBT is efficacious in the

treatment of school-refusing children. Eighty-eight

percent of the CBT children in contrast to 29% of

the wait-list children showed clinical improvement

in school attendance. Last and colleagues conducted

a study randomizing 56 children to either a 12-week

CBT group or an attention-placebo control group.37

The CBT condition consisted of graduated in vivo

exposure, cognitive restructuring and coping selfstatement training. The attention-placebo control

group received educational-support therapy. The

findings revealed no statistically significant differences between the CBT children and the educational-support-therapy children. Both groups showed

improvements on a variety of measures, including

school attendance.

Generally, medications are considered as part of a

multimodal treatment plan for children and adolescents diagnosed with anxiety disorders. To our

knowledge, there is only one study that has investigated a multimodal treatment for school refusal.

Bernstein and colleagues7 investigated the efficacy

of eight weeks of imipramine versus placebo, with

each group receiving cognitive-behavioral therapy

for the treatment of school-refusing adolescents. A

noteworthy fact regarding this study is that major

depressive disorder was not an exclusion criterion as

it is in many of the other studies reviewed. Anxiety

and depressive symptoms improved for both groups;

however, school attendance lagged in the placebo

group. The low response rate with the placebo-plusCBT group can be explained by the fact that school

refusers with comorbid depression and anxiety have

more severe symptoms. These findings support a

multimodal treatment approach using pharmacotherapy plus CBT.

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Recently, there has been a dramatic increase in

the knowledge of the phenomenology of PTSD in

children. This may be due in part to the increasing

number of children who are exposed to violence.

Giaconia and colleagues found that by age 18 years,

greater than two-fifths of youths in a community

sample met criteria for at least one trauma, and more

than 6% met criteria for a lifetime diagnosis of

PTSD.38 The hallmark features of PTSD involve

symptoms from three clusters: 1) persistent re-experiencing of the event, 2) avoidance of reminders of

the event and numbing of responsiveness, and 3)

persistent symptoms of arousal. It is important to

note that often children may not meet full diagnostic

criteria but still have symptoms that are significant

VOL. 97, NO. 1, JANUARY 2005 21

ANXIETY DISORDERS TREATMENT

enough to warrant treatment. Another factor to bear

in mind when considering treatment is the comorbidity associated with PTSD. Youths with a diagnosis of PTSD have an increased risk of depression,

other anxiety disorders and substance use disorders.38 There is a paucity of controlled studies in the

literature evaluating effective treatment for PTSD in

children. Much ofthe literature has focused on treatment of sexually abused children. In a study by

Cohen and Mannarino,39 cognitive-behavioral therapy was found to have superior clinical efficacy compared with nondirective supportive therapy in the

treatment of sexually abused preschool-age children

with emotional and behavioral symptomatology.

Deblinger et al. evaluated the effects of participation

by mothers in cognitive-behavioral interventions for

sexually abused children with PTSD symptoms.40

Families were randomly assigned to one of three

conditions: child only, mother only, or child and

mother. A community condition served as the control group. The cognitive-behavioral interventions

were significantly more effective than the community control group. The groups that included the child

in treatment were also more efficacious than the

mother only group. As in the study by Barrett,"1

parental involvement in CBT resulted in a reduction

of reported externalizing behavior by the participating parent. Deblinger and colleagues completed a

two-year follow-up of the 100 children in the initial

study.41 The results of this study indicate that the

improvements in externalizing behavior, depression

and PTSD were maintained over the two-year period. There was a slight but significant deterioration

in the effectiveness of parenting practices for the

mothers that had participated in treatment at the

one-year follow-up. King et al.42 had the first published randomized clinical trial to use a wait-list

condition to examine the efficacy of CBT for sexually abused children with PTSD symptoms. The

children were randomly assigned to one of three

groups: child CBT, family CBT or wait-list condition. Children in the treatment condition received 20

weekly individual sessions aimed at helping the

child overcome his or her postabuse distress and

PTSD symptoms. Treatment resulted in a significant

reduction of PTSD symptoms in all three clusters.

However, there was no significant improvement

related to caregiver involvement.

Specific Phobia

DSM-IV defines a specific phobia as an excessive and unreasonable fear of circumscribed objects

or situations where the avoidance, anxiety or distress

related to the fear is associated with functional

impairment or significant distress.6 Children may

not realize that their fears are marked or unreason22 JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL MEDICAL ASSOCIATION

able. Ollendick and Francis reported the prevalence

rate of specific phobias to be 3-4% of the population.43 There is a paucity of randomized controlled

trials on treating childhood phobias. Silverman et al.

conducted a study evaluating the relative efficacy of

an exposure-based contingency management (CM)

treatment condition and an exposure-based cognitive

self-control (SC) treatment condition to an education support (ES) control condition for the treatment

of childhood phobic disorders."4 The majority of the

subjects (N=87) met criteria for specific phobia, and

the remainder met criteria for social phobia (N=10)

and agoraphobia (N=7). The findings indicate that

both the CM and SC conditions were efficacious in

treating phobic children. What was unexpected was

the level of improvement in the ES condition. More

research is needed to determine what components of

the attention placebo mediate improvement.

Limitations

The controlled studies that have been conducted

tend to have several limitations in common. One is

the small size of the groups. Many of the studies

reviewed here had low participation and/or relatively

high attrition rates. A second concern regarding

these studies is generalizability. Many of the major

comorbid diagnoses met exclusion criteria. Given

that anxiety disorders commonly occur with depression, substance abuse and other anxiety disorders,

researchers need to take this into account when

designing studies and applying the results to clinical

populations. Along those same lines, the demographic make-up of studies needs to reflect the

demographics of the treatment population; otherwise, we can only extrapolate the results to certain

groups of children. A third concern is the small

number of studies comparing two treatment modalities. It is difficult to know which modalities are efficacious in combination or alone and how the results

compare to each other versus placebo.

DISCUSSION

Anxiety disorders are very common during the

childhood/adolescence period and because of the

chronicity, severity and comorbidity, children need

to be identified early, and treatment needs to be initiated to limit the deleterious effects on function.

Although there are many modalities of treatment

being used for the various disorders, few have been

validated by rigorous controlled studies. This underscores the importance of conducting controlled trials. Further, these trials will add to the options of

available evidenced-based treatments for anxiety

disorders in this population. Table 1 provides an

overview of the controlled trials of anxiety disorder

treatment for children and adolescents and offers the

VOL. 97, NO. 1, JANUARY 2005

ANXIETY DISORDERS TREATMENT

reader a quick review of the trials. Even though

there seem to be a number of hurdles to leap in

empirically validating interventions for the treatment of childhood anxiety disorders, researchers

have accomplished a tremendous amount within the

last decade and are continuing to make strides to

ensure that our children receive optimal treatment

that will improve their quality of life. Clinicians and

researchers should make the most use of what has

been done in the past decade and use the knowledge

and data as a springboard for future studies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors wish to gratefully acknowledge Alva

Blair, Robyn Mixon and Rachel Friendly for their

assistance with the preparation ofthis manuscript.

REFERENCES

1. Klein RG, Pine DS. Anxiety disorders. In: Rutter M, Taylor E, Hersor L, eds.

Child and adolescent psychiatry: Modern Approaches, 4th ed. London:

Blackwell Scientific; in press.

2. Pine DS. Childhood anxiety disorders. Curr Opinion Pediatrics. 1997;9:329338.

3. Shaffer D, Fisher P, Dulcan MK, et al. The NIMH diagnostic interview

schedule for children version 2.3: description, acceptability, prevalence

rates, and performance in the MECA study: methods for the epidemiology

of child and adolescent mental disorders study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc

Psychiatry. 1996;35:865-877.

4. Kashani JH, Orvaschel H. Anxiety disorders in mid-adolescence: a community sample. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145:960-964.

5. March JS, Biederman J, Wolkow R, et al. Sertraline in children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: a multicenter randomized

controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;280:1752-1756.

6. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. text revision (DSM-IV-TR). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

7. Bernstein GA, Borchardt CM, Perwein AR, et al. Imipramine plus cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of school refusal. J Am Acad

Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:276-283.

8. Kendall PC, Warman MJ. Anxiety disorders in youth: diagnostic consistency across DSM-111-R and DSM-IV. J Anxiety Disord. 1996;10:452-463.

9. Bowen RC, Offord DR, Boyle MH. The prevalence of overanxious disorder

and separation anxiety disorder: results from the Ontario child health study.

J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1990;29:753-758.

10. Kendall PC. Treating anxiety disorders in children: results of a randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1994;62:100-1 10.

11. Barrett PM, Dadds MR, Rapee RM. Family treatment of childhood anxiety: a controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64:333-342.

12. Kendall PC, Flannery-Schroeder E, Panichelli-Mindel SM, et al. Therapy

for youths with anxiety disorders: a second randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65:366-380.

13. Barrett PM. Evaluation of cognitive-behavioral group treatments for

childhood anxiety disorders. J Clin Child Psychol. 1998;27:459-468.

14. Silverman WK, Kurtines WM, Ginsburg GS, et al. Treating anxiety disorders in children with group cognitive-behavioral therapy: a randomized

clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:995-1003.

15. Krohne HW, Hock M. Relationships between restrictive mother-child

interactions and anxiety of the child. AnxietyResearch. 1991:4:109-124.

16. Mendlowitz SL, Manassis K, Bradley S, et al. Cognitive-behavioral group

treatments in childhood anxiety disorders: the role of parental involvement. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38:1223-1229.

17. Shortt AL, Barrett PM, Fox TL. Evaluating the FRIENDS program: a cognitive-behavioral group treatment for anxious children and their parents. J

Clin Child Psychol. 2001:30:525-535.

18. Beidel DC, Turner SM, Morris TL. Behavioral treatment of childhood

JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL MEDICAL ASSOCIATION

social phobia. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:1072-1080.

19. Pediatric Psychopharmacology Anxiety Study Group. Fluvoxamine for

the treatment of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. N Eng J

Med. 2001 ;344:1279-1285.

20. Rynn MA, Siqueland L, Rickels K. Placebo-controlled trial of sertraline in

the treatment of children with generalized anxiety disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:2008-2014.

21. Costello EJ, Burns BJ, Angold A, et al. How can epidemiology improve

mental health services for children and adolescents? J Am Acad Child

Adolesc Psychiatry. 1993;32:1 106-1113.

22. Flament MF, Whitaker A, Rapoport JL. Obsessive-compulsive disorder in

adolescence: an epidemiological study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1988;27:766-771.

23. Valleri-Basile LA, Garrison CZ, Jackson KL. Frequency of obsessive-compulsive disorder in a community sample of young adolescents. J Am Acad

Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994;33:782-791.

24. Zohar AH. The epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder in children and adolescents. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 1999;8:445-460.

25. DeVeaugh-Geiss J, Moroz G, Biederman J, et al. Clomipramine

hydrochloride in childhood and adolescent obsessive-compulsive disorder: a multicenter trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1992;31:45-49.

26. Riddle MA, Scahill L, King RA, et al. Double-blind, crossover trial of fluoxetine and placebo in children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive

disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1992;31 :1062-1069.

27. Geller DA, Hoog SL, Heiligenstein JH, et al. Fluoxetine treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder in children and adolescents: a placebo-controlled

clinical trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:773-779.

28. Riddle MA, Reeve EA, Yaryura-Tobias JA, et al. Fluvoxamine for children

and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized controlled multicenter trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:222-229.

29. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice

parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents

with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.

1 998;37(suppl):27S-45S.

30. De Haan E, Hoogduin KAL, Builelaar JK, et al. Behavior therapy versus

clomipramine for the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder in children

and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:1022-1029.

31. March JS, Mulle K, Herbel B. Behavioral psychotherapy for children and

adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: an open trial of a new

protocol-driven treatment package. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.

1994;33:333-341.

32. King NJ, Bernstein GA. School refusal in children and adolescents: a

review of the past 10 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:

197-205.

33. Burke AE, Silverman WK. The prescriptive treatment of school refusal.

Clin Psychol Rev. 1987;7:353-362.

34. Kearney CA, Roblek TL. Parent training in the treatment of school refusal

behavior. In: Briesmeister JM, Schaefer CD, eds. Handbook of Parent Training: Parents as Co-Therapists for Children's Behavior Problems, 2nd ed.

New York: Wiley; 1997.

35. King NJ, Ollendick TH, Tonge BJ. School refusal: assessment and treatment. Boston: Allyn and Bacon; 1995.

36. King NJ, Tonge BJ, Heyne D, et al. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of

school refusing children: a controlled evaluation. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:395-403.

37. Last CG, Hansen C, Franco N. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of

school phobia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:404-41 1.

38. Giaconia RM, Reinherz HZ, Silverman AB, et al. Traumas and posttraumatic stress disorder in a community population of older adolescents. J Am

Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34:1369-1380.

39. Cohen JA, Mannarino AP. A treatment study for sexually abused preschool children: initial findings. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;

35:42-50.

40. Deblinger E, Lippman J, Steer R. Sexually abused children suffering posttraumatic stress symptoms: initial treatment outcome findings. Child Maltreat. 1996;1:310-321

41. Deblinger E, Steer RA, Lippman J. Two-year follow-up study of cognitive-behavioral therapy for sexually abused children suffering posttraumatVOL. 97, NO. 1, JANUARY 2005 23

ANXIETY DISORDERS TREATMENT

ic stress symptoms. Child Abuse Neglect. 1999;23:1371-1378.

42. King NJ, Tonge BJ, Mullen P, et al. Treating sexually abused children with

posttraumatic stress symptoms: a randomized clinical tral. J Am Acad Child

Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:1347-1355.

43. Ollendick T, Francis G. Behavioral assessment and treatment of child-

v EDUCATION

hood phobias. Behavior Modification. 1988;12:165-204.

44. Silverman WK, Kurtines WM, et al. Contingency management, self-control and education support in the treatment of childhood phobic disorders:

a randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:675-687. a

V WOMEN

v OBESITY

JNMA would like to publish three "theme issues" in calendar year 2005 covering

the following topics: (1 ) Education {to include the undergraduate medical school

curriculum, updates on medical schools with special emphasis on the historically

black institutions and residency/fellowship issues}, (2) women/children issues and

(3) obesity/metabolic syndrome. This is a "call for manuscripts" in all three areas.

The timeliness and scholarship of submissions will determine whether any or all of

these initiatives come to fruition. This is JNMA's first foray in this area and

submissions can be "open-ended". In subsequent years we would hope to have

more focused submissions.

Please indicate the particular "theme issue" in your cover letter. Submission

guidelines are located in at least every other issue of JNMA, on NMA's website at

www.nmanet.org under publications, JNMA. Please e-mail your submissions to

isheyn@nma net.org.

FNMMA.

Eddie Hoover, MD i

JNMA Editor-in-Chiefm

24 JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL MEDICAL ASSOCIATION

VOL. 97, NO. 1, JANUARY 2005

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Complete Ca1 Prelim ReviewersDocumento37 pagineComplete Ca1 Prelim ReviewersANDREW DEL ROSARIONessuna valutazione finora

- Grieco Et Al-2023-Intensive Care MedicineDocumento4 pagineGrieco Et Al-2023-Intensive Care MedicineDr Vikas GuptaNessuna valutazione finora

- Daftar Pustaka: LUTFIANA DESY S, Drs. Gede Bayu Suparta, MS., PH.DDocumento3 pagineDaftar Pustaka: LUTFIANA DESY S, Drs. Gede Bayu Suparta, MS., PH.DanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Mental Health DirectoryDocumento24 pagineMental Health DirectoryCMO Bestla GroupNessuna valutazione finora

- The Bradley Method® Course ContentDocumento1 paginaThe Bradley Method® Course ContentbirthmommaNessuna valutazione finora

- DMSCO Log Book Vol.3 7/1925-6/1926Documento109 pagineDMSCO Log Book Vol.3 7/1925-6/1926Des Moines University Archives and Rare Book RoomNessuna valutazione finora

- Checklist For Initiating Gender Affirming Hormone Treatment 1Documento1 paginaChecklist For Initiating Gender Affirming Hormone Treatment 1Cara ThanomkulNessuna valutazione finora

- Rguhs Thesis Topics in AnesthesiaDocumento5 pagineRguhs Thesis Topics in AnesthesiaDltkCustomWritingPaperMurfreesboro100% (2)

- Text 918-553-8061Documento4 pagineText 918-553-8061MD6Nessuna valutazione finora

- FDA Bans Times Natural Capsules, X Plus Men, OthersDocumento2 pagineFDA Bans Times Natural Capsules, X Plus Men, OthersGhanaWeb EditorialNessuna valutazione finora

- 2021 SAISD Mask Mandate-LetterheadDocumento2 pagine2021 SAISD Mask Mandate-LetterheadDavid IbanezNessuna valutazione finora

- Deepu Pps Front PgesDocumento6 pagineDeepu Pps Front PgesM. Shoeb SultanNessuna valutazione finora

- Alma Ata DeclarationDocumento3 pagineAlma Ata DeclarationGeorgios MantzavinisNessuna valutazione finora

- W.G. NHMDocumento48 pagineW.G. NHMRajesh pvkNessuna valutazione finora

- Procedur Injection (Group 9)Documento16 pagineProcedur Injection (Group 9)Shinta HerawatiNessuna valutazione finora

- Minnie Germano New Resume 2023Documento1 paginaMinnie Germano New Resume 2023api-655682809Nessuna valutazione finora

- Injection TechniqueDocumento47 pagineInjection TechniqueGeminiQueenNessuna valutazione finora

- OET Discharge Letter - Sample Letter For Doctors and NursesDocumento5 pagineOET Discharge Letter - Sample Letter For Doctors and NursesClassNessuna valutazione finora

- Personal StatementDocumento2 paginePersonal StatementShahryar Ahmad KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Jkt-g11-Ielts-Assignment 1 (10 Aug 21)Documento4 pagineJkt-g11-Ielts-Assignment 1 (10 Aug 21)Novantho NugrohoNessuna valutazione finora

- Research Paper On Knowledge Management Practices in Pharma CompanyDocumento7 pagineResearch Paper On Knowledge Management Practices in Pharma Companyafnhekkghifrbm100% (1)

- Children's Miracle Network Presents Capital GrantsDocumento3 pagineChildren's Miracle Network Presents Capital GrantsNewzjunkyNessuna valutazione finora

- Cancer Registry Standard Operating ProceduresDocumento3 pagineCancer Registry Standard Operating ProceduresAnan AghbarNessuna valutazione finora

- 9 Key Radiology Medical Coding Tips For CodersDocumento4 pagine9 Key Radiology Medical Coding Tips For Codersayesha100% (1)

- 23andme and The FDADocumento4 pagine23andme and The FDAChristodoulos DolapsakisNessuna valutazione finora

- OET Test 14Documento10 pagineOET Test 14shiela8329gmailcomNessuna valutazione finora

- TM1 PresentationDocumento33 pagineTM1 PresentationJas Sofia90% (10)

- Article1381852119 NwokoDocumento8 pagineArticle1381852119 NwokoChukwukadibia E. NwaforNessuna valutazione finora

- 6 Pharmacists in Public HealthDocumento22 pagine6 Pharmacists in Public HealthJoanna Carla Marmonejo Estorninos-Walker100% (1)

- P4 - Primary and Secondary Survey in EmergencyDocumento22 pagineP4 - Primary and Secondary Survey in Emergencylia agustinaNessuna valutazione finora