Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Aliment Vegetar

Caricato da

Om CinstitCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Aliment Vegetar

Caricato da

Om CinstitCopyright:

Formati disponibili

10136_digenova.

qxd

02/03/2007

2:07 PM

Page 185

NUTRITION SUBSPECIALTY ARTICLE

Infants and children consuming atypical diets:

Vegetarianism and macrobiotics

Tanya Di Genova1, Harvey Guyda MD2

lternative diets have been recognized for centuries. In

his 1813 pamphlet, A Vindication of Natural Diet, the

poet Shelley wrote, There is no disease, bodily or mental,

which adoption of vegetable diet and pure water has not

infallibly mitigated, wherever the experiment has been

fairly tried (1).

In the rapidly expanding multicultural population of

North America, vegetarianism is a popular dietary practice.

It may be based on religious or cultural beliefs, or on economic, health or ethical concerns. A 2002 survey (2) found

that approximately 4% of Canadian adults consumed a vegetarian diet that excluded meat, poultry and fish.

Furthermore, 20% to 25% of adults in the United States

reported eating four or more meatless meals weekly, or that

they usually or sometimes maintain a vegetarian diet, suggesting an increasing interest in vegetarianism (2). Because

parents are the principal providers of what their infants eat,

vegetarian parents often wean their children onto the familys vegetarian diet. It is important to note that atypical

diets are more likely to cause problems of malnutrition in

children than in adults due to their greater nutrient

requirements relative to body weight. Thus, without the

appropriate care for these children, health issues may arise

that could concern health care professionals.

Vegetarianism is a very broad category consisting of diets

with varying degree of animal product consumption. This

distinction is important because the more strictly vegetarianism is followed, the more difficult it becomes to guarantee an adequate diet for growing infants and children. For

example, lacto-ovo-vegetarians include eggs, milk and dairy

products along with a plant food selection; however, they

refrain from animal flesh. On the other hand, a lactovegetarian diet consists of plant foods such as grains,

legumes, nuts, fruits and vegetables, complemented with

milk and milk products, with avoidance of eggs and animal

flesh. Pure or total vegetarians (or vegans) reject all foods

of animal origin, including milk and eggs. Finally, another

atypical diet that is far more restrictive than pure vegetarianism is the macrobiotic diet. The original macrobiotic

dietary regimen comprised of 10 diets, ranging from the

lowest level, which includes 10% cereal, 30% vegetables,

10% soups, 30% animal products, 15% salads and fruits, and

5% desserts, to the highest level, which is composed of

100% cereals (3). The revised macrobiotic diet may contain

whole-grain cereals (mainly unpolished rice), vegetables

and pulses, with small additions of seaweeds, fermented

foods, nuts, seeds and seasonal fruit (4).

POTENTIAL BENEFITS

There have been few studies looking at the long-term

health outcomes of vegetarian or macrobiotic diets in

children. Adult vegetarians have lower intakes of fat, a

lower body mass index and lower mean serum cholesterol

levels than nonvegetarian individuals (2). Thus, these findings suggest an indirect effect on reducing the prevalence of

coronary artery disease, with a potential decreased risk of

mortality in the future (2). In addition, a large study of

adults conducted in 1984 showed that Seventh-day

Adventists, proponents of a vegetarian culture, have lower

age-specific mortality rates than the nonvegetarian

population (5).

POTENTIAL CONCERNS

The American Dietetic Association (2) and the American

Academy of Pediatrics (6) state that a well-planned vegan

diet can, in fact, support adequate nutrition in the growing

child. However, as health care professionals, we should

become concerned when foods within strict vegetarian

diets or macrobiotic diets are not appropriately chosen

and/or lack adequate supplementation.

Protein intake

Total protein in vegetable-based foods is lower than in animal sources; plant protein is less digestible than animal protein; and many vegetable proteins are deficient in one or

more essential amino acids (5). Nevertheless, human physiological requirements for a well-balanced source of amino

acids can be met if a variety of plant proteins are consumed,

and additionally, if caloric needs are met (7).

However, diets such as the macrobiotic diet are more

restrictive during infancy and are of greater concern. One

study (8) of Dutch infants on a macrobiotic diet, ranging in

of Medicine, McGill University; 2Department of Pediatrics, Montreal Childrens Hospital, McGill University Health Centre, Montreal,

Quebec

Correspondence: Dr Harvey Guyda, Department of Pediatrics, Montreal Childrens Hospital, 2300 Tupper Street, Montreal, Quebec H3H 1P3.

Telephone 514-412-4467, fax 514-412-4251, e-mail harvey.guyda@mcgill.ca

Accepted for publication January 25, 2007

1Faculty

Paediatr Child Health Vol 12 No 3 March 2007

2007 Pulsus Group Inc. All rights reserved

185

10136_digenova.qxd

02/03/2007

2:07 PM

Page 186

Di Genova and Guyda

age from six to eight months, found that 59% of infants had

a protein intake of less than 80% of the Dutch recommended

daily intake.

Energy intake

As a vegetarian diet becomes more restrictive, the energy

intake requirements become more difficult to attain. The

vegetarian diet is a bulky one that can restrict energy intake

in children. Furthermore, energy intake in infants receiving

macrobiotic diets compared with vegetarian diets is considerably lower than the recommended requirements (9). A

major potential concern relates to the expanding knowledge of the critical window of early environmental influences on subsequent child development and health (10).

Because the energy density of macrobiotic diets is lowest in

infants during the weaning period of 10 to 12 months of

age, this diet could adversely affect their future growth and

development (11).

The growth of a child is a sensitive indicator of the

potential negative effects of vegetarian, vegan and macrobiotic diets. Children younger than two years of age who were

fed vegetarian or vegan diets exhibited significant lower

mean weight and length velocities (12) and were overall

lighter in weight and smaller in stature than reference populations (13). The Farm Study (14) analyzed 404 children

from a vegetarian community in which parents were well

educated about the diet and children were supplemented

with the appropriate minerals and vitamins. While these

vegetarian children were within the 25th and 75th percentiles for United States growth standards, height for age

and weight for age were below the median when compared

with reference populations for most ages. Values were statistically significant for children younger than five years of

age. Thus, with the appropriate supplementation and parent education, children on vegetarian or vegan diets can

attain adequate growth, but it may be somewhat less than

reference populations.

In children following macrobiotic diets, weight and

length were more depressed when compared with vegetarian

children (15). A marked decline from the median for reference weight, and height and arm circumference, was

observed between six months and two years of age, following which a partial catch-up for weight and arm circumference was reached, given no change in diet. However, no

catch-up growth in height occurred in macrobiotic children,

which may indicate the existence of chronic nutritional deficiencies that do not allow for adequate catch-up growth (4).

Vitamin D

Because vitamin D is most commonly found in fortified

milk products, egg yolk or oily fish, it is the most likely vitamin to be deficient in vegetarian and macrobiotic diets, but

not in lacto-ovo-vegetarian diets. Exposure to sunlight may

be an unreliable source of vitamin D, especially in northern

areas and dark-skinned infants; thus, supplementation is

important to avoid an increased risk of osteoporosis or

rickets (16).

186

Vitamin B12

Plant foods are not a high-quality source of vitamin B12.

Thus, it is not surprising that studies have shown low serum

concentrations of vitamin B12 in children on vegan and

macrobiotic diets without supplementation (4). Vitamin

B12 deficiency is not a benign condition; it may lead to

megaloblastic anemia and neurological disorders. Mild vitamin B12 deficiency in infancy, with or without hematological signs of deficiency, may be associated with impaired

cognitive performance in adolescence, specifically, fluid

intelligence (which involves reasoning, the capacity to

solve complex problems, abstract thinking ability and the

ability to learn), spatial ability and short-term memory

(17). Moreover, lack of cobalamin may lead to long-term

neurological disorders in infants and toddlers fed vegetarian

diets (18). In addition, recent data indicate that the adverse

effects of cobalamin deficiency in the macrobiotic community may not be restricted to just early childhood, but may

also cause symptoms related to impaired cobalamin status

later in life. Even a change to a lacto-ovo-vegetarian or

omnivorous diet at six years of age is not sufficient to restore

normal cobalamin status in previously strict macrobiotic

adolescents (19). Thus, it is obvious that vitamin B12

supplementation for children consuming vegan and macrobiotic diets is essential to ensure normal growth and

development.

Iron

Iron intakes in vegan preschoolers have been shown to be

above the current recommended daily allowance (20);

however, nonheme iron from plants is less bioavailable than

heme iron from animal sources. Consequently, iron deficiency anemia has been shown in many studies to occur in

vegetarian children and in a greater proportion of macrobiotic children (4). Iron deficiency is also not a benign condition, because anemic infants may have significantly lower

Mental and Psychomotor Developmental Index scores

compared with control infants (4). Thus, iron is another

nutrient that should be monitored in children who follow

atypical diets.

Calcium

Calcium intake for vegan and macrobiotic children may be

below current recommendations (2), and their diets may

contain substances found in plant foods that may impair

calcium absorption (2). Low calcium may result in rickets

(4) and reduced bone mineral content or osteoporosis (21),

with important implications for future fracture risk.

Therefore, foods rich in calcium, or calcium itself, should be

supplemented to assure adequate intake.

IS THERE A REAL CAUSE FOR CONCERN?

As noted above, a well-planned and carefully followed vegetarian diet can satisfy the nutrient requirements for infants

and children, and thus cause no real concern. However, the

deleterious effects that these atypical diets can have on

infants and children, such as scurvy, rickets and kwashiorkor,

Paediatr Child Health Vol 12 No 3 March 2007

10136_digenova.qxd

02/03/2007

2:07 PM

Page 187

Vegetarianism and macrobiotics

are well documented (22). Further, Dagnelie and

van Staveren (4) found that infants weaned onto

macrobiotic diets were significantly slower in gross motor

development, especially locomotion, and to a lesser degree

in speech and language development. Moreover, major skin

and muscle wasting occurred in 30% of macrobiotic infants.

The more restrictive diets, such as the vegan and

macrobiotic diets, have attracted some negative attention

in the media due to the serious health concerns they may

cause. In some cases, parents have rejected treatment for

the documented nutritional deficiencies, and legal

intervention was necessary to protect the health and safety

of the child. In 2002, a vegan couple from New Zealand was

accused of child abuse after failing to provide the necessities of life for their six-month-old child. Their son died of

medical complications due to vitamin B12 deficiency after

the parents left the hospital against medical advice to treat

their son with herbal remedies (23). In addition, seven

infants exclusively breastfed by vegan mothers developed

nutritional vitamin B12 deficiency. Most of these children

presented with hypotonia, lengths and weights below the

third percentile, and psychomotor retardation that

improved with the appropriate nutritional supplementation

(24).

As recently as 2005, despite the significant available

literature on the potential risks of alternate diets, strict

vegan parents were taken to court and charged with neglect

after one of their children died of malnutrition (25). Their

other four children were all found to be below the lowest

appropriate percentile for height and weight for their age.

These parents avoided taking their children to see physicians and the children were not immunized.

It is important to consider that the number of subjects is

small in the majority of the negative studies cited above,

and long-term consequences were not often discussed.

Nevertheless, these reports are alarming enough to suggest

that extra time is warranted by the physician caring for

infants following atypical diets, with institution of appropriate laboratory investigation and supplementation as

required.

While appropriately planned vegan diets can satisfy the

nutrient needs of infants, a lack of communication with

their parents and, in some cases, with the spiritual leaders of

their community can hinder the identification of infants at

risk. It is important for parents to receive education from

reliable sources of information, such as paediatricians,

nutritionists and nurses, on the diet that they have chosen.

It is also important that these children be kept within the

medical care system because it is not uncommon for these

diets to be associated with cultures that shy away from

orthodox medical treatments. An earlier survey (26)

showed that only 9% of British vegans approved of routine

childhood immunization and only 38% sanctioned blood

transfusions, compared with 91% and 97%, respectively,

for the population at large. The authors believe that this

36-year-old study warrants re-evaluation in the 21st

century.

Paediatr Child Health Vol 12 No 3 March 2007

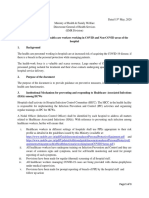

TABLE 1

Guidelines recommended for children being weaned onto

a vegetarian diet

Protein

Inclusion of one or more servings of 150 g/day to 250 g/day of

dairy products in nonvegans.

Vegan alternate: Use more bean and soy products that are

higher in lysine compared with cereals. Ensure a

variety of plant foods and cereal-legume combinations to

achieve 1.5 g/kg/day for children younger than

four years of age, and 1.0 g/kg/day thereafter.

Energy

Addition of dietary fat to increase energy intake by 25% to

30% by including 20 g/day to 25 g/day of vegetable oil

or 40 g/day to 50 g/day of nuts and seeds.

Vitamin D

Inclusion of 100 g/week to 150 g/week of fatty fish supplies

2 g/day to 3 g/day.

Vegan alternate: 250 mL of vitamin D-fortified soymilk

provides 1.5 g/day to 3 g/day. Added supplements of

vitamin D: 2 g/day to 3 g/day as required.

Vitamin B12

Inclusion of 100 g/week to 150 g/week of fatty fish.

Vegan alternate: 125 mL vitamin B12-fortified soymilk supplies

the current recommended requirement of 0.9 g/day

to 1.3 g/day.

Iron

Vegetarian and nonvegetarian children require 1.0 mg/kg/day

after four to six months of age. Iron-rich foods include

soy foods, legumes, nuts, breads and cereals. The addition

of sources of vitamin C to meals increases iron

bioavailability (eg, citrus fruit, tomatoes, potatoes,

strawberries and spinach).

Calcium

Six to 12 servings of calcium-rich foods should be

consumed every day, which may include one serving of

dairy products at 150 g/day to 250 g/day.

Vegan alternate: 125 mL of calcium-fortified soymilk.

Reduction of fibre intake to 0.5 g/kg/day to increase

calcium absorption.

Data from references 4, 27 and 28

SUMMARY

Table 1 summarizes current recommendations for children

being weaned onto a vegetarian diet (4,27,28). Children

consuming atypical diets are not uncommon and are on the

rise, as judged by the plethora of information on veganism

directed to those caring for children. For example, an

Internet search of the terms vegan and children produced

1,380,000 hits. Without the appropriate monitoring and

supplementation, these diets may have deleterious effects

on a childs health outcomes. Nutritional deficiencies, particularly early in life, may adversely affect growth, bone

mineral content, and motor and cognitive development.

Most significantly, it is important to recognize that

although it is the 21st century, children may still die as a

consequence of being placed on these atypical diets by their

parents without appropriate care and supervision. Because

these deleterious affects can be avoided, it is highly recommended that child health practitioners carefully review

dietary intake, including all supplements, when interviewing parents who provide these atypical diets (especially during infancy and early childhood) and make the appropriate

interventions.

187

10136_digenova.qxd

02/03/2007

2:07 PM

Page 188

Di Genova and Guyda

REFERENCES

1. Ellis FR, Mumford P. The nutritional status of vegans and

vegetarians. Proc Nutr Soc 1967;26:205-12.

2. American Dietetic Association; Dietitians of Canada. Position of

the American Dietetic Association and Dietitians of Canada:

Vegetarian diets. J Am Diet Assoc 2003;103:748-65.

3. Zen macrobiotic diets. JAMA 1971;218:397.

4. Dagnelie PC, van Staveren WA. Macrobiotic nutrition and child

health: Results of a population-based, mixed-longitudinal cohort

study in The Netherlands. Am J Clin Nutr

1994;59(Suppl 5):1187S-96S.

5. Adler M, Specker B. Atypical diets in infancy and early childhood.

Pediatr Ann 2001;30:673-80.

6. American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Nutrition.

Pediatric Nutrition Handbook, 4th edn. Elk Grove Village:

American Academy of Pediatrics, 1998.

7. Young VR, Pellett PL. Plant proteins in relation to human protein

and amino acid nutrition. Am J Clin Nutr

1994;59(Suppl 5):1203S-12S.

8. Dwyer JT, Dietz WH Jr, Andrews EM, Suskind RM. Nutritional

status of vegetarian children. Am J Clin Nutr 1982;35:204-16.

9. Sanders TA. Vegetarian diets and children. Pediatr Clin North Am

1995;42:955-65.

10. De Bellis MD. The psychobiology of neglect. Child Maltreat

2005;10:150-72.

11. Dagnelie PC, van Staveren WA, Verschuren SA, Hautvast JG.

Nutritional status of infants aged 4 to 18 months on macrobiotic

diets and matched omnivorous control infants: A population-based

mixed-longitudinal study. I. Weaning pattern, energy and nutrient

intake. Eur J Clin Nutr 1989;43:311-23.

12. Shull MW, Reed RB, Valadian I, Palombo R, Thorne H, Dwyer JT.

Velocities of growth in vegetarian preschool children. Pediatrics

1977;60:410-7.

13. Sanders TA. Growth and development of British vegan children.

Am J Clin Nutr 1988;48(Suppl 3):822-5.

14. OConnell JM, Dibley MJ, Sierra J, Wallace B, Marks JS, Yip R.

Growth of vegetarian children: The Farm Study. Pediatrics

1989;84:475-81.

188

15. van Staveren WA, Dhuyvetter JH, Bons A, Zeelen M, Hautvast JG.

Food consumption and height/weight status of Dutch preschool

children on alternative diets. J Am Diet Assoc 1985;85:1579-84.

16. Dwyer JT, Dietz WH Jr, Hass G, Suskind R. Risk of nutritional

rickets among vegetarian children. Am J Dis Child 1979;133:134-40.

17. Louwman MW, van Dusseldorp M, van de Vijver FJ, et al. Signs of

impaired cognitive function in adolescents with marginal

cobalamin status. Am J Clin Nutr 2000;72:762-9.

18. Graham SM, Arvela OM, Wise GA. Long-term neurologic

consequences of nutritional vitamin B12 deficiency in infants.

J Pediatr 1992;121:710-4.

19. van Dusseldorp M, Schneede J, Refsum H, et al. Risk of persistent

cobalamin deficiency in adolescents fed a macrobiotic diet in early

life. Am J Clin Nutr 1999;69:664-71.

20. Fulton JR, Hutton CW, Stitt KR. Preschool vegetarian children.

J Am Diet Assoc 1980;76:360-5.

21. Parsons TJ, van Dusseldorp M, van der Vliet M, van de Werken K,

Schaafsma G, van Staveren WA. Reduced bone mass in Dutch

adolescents fed a macrobiotic diet in early life. J Bone Miner Res

1997;12:1486-94.

22. Roberts IF, West RJ, Ogilvie D, Dillon MJ. Malnutrition in infants

receiving cult diets: A form of child abuse. Br Med J 1979;1:296-8.

23. Second Opinions. Vegan Child Abuse. <www.second-opinions.

co.uk/child_abuse.html> (Version current at February 14, 2007).

24. Roschitz B, Plecko B, Huemer M, Biebl A, Foerster H, Sperl W.

Nutritional infantile vitamin B12 deficiency: Pathobiochemical

considerations in seven patients. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed

2005;90:F281-2.

25. Grinberg E. Vegan parents on trial for babys death, allegedly from

malnutrition. <http://news.findlaw.com/court_tv/s/20051018/

18oct2005172836.html> (Version current at February 14, 2007).

26. McKenzie J. Profile on vegans. Plant Foods Hum Nutr

1971;2:79-88.

27. MacLean WC Jr, Graham GG. Vegetarianism in children.

Am J Dis Child 1980;134:513-9.

28. Messina V, Melina V, Mangels AR. A new food guide for North

American vegetarians. J Am Diet Assoc 2003;103:771-5.

Paediatr Child Health Vol 12 No 3 March 2007

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Zinc DeficiencyDocumento12 pagineZinc DeficiencyOm CinstitNessuna valutazione finora

- Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: Costing ReportDocumento32 pagineIdiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: Costing ReportOm CinstitNessuna valutazione finora

- BalintDocumento4 pagineBalintOm CinstitNessuna valutazione finora

- BreastEnlargementInfants PDFDocumento2 pagineBreastEnlargementInfants PDFOm CinstitNessuna valutazione finora

- Acta Who PDFDocumento106 pagineActa Who PDFOm CinstitNessuna valutazione finora

- Child Growth Standars and The Identification of Severe Malnutricion in ChildsDocumento12 pagineChild Growth Standars and The Identification of Severe Malnutricion in Childspastizal123456Nessuna valutazione finora

- ItaloDocumento2 pagineItaloOm CinstitNessuna valutazione finora

- History Taking and Clinical ExaminationDocumento129 pagineHistory Taking and Clinical ExaminationYen ChouNessuna valutazione finora

- Georg Trakl Is An Important Lyric Poet in German Literature of The Early Twentieth CenturyDocumento2 pagineGeorg Trakl Is An Important Lyric Poet in German Literature of The Early Twentieth CenturyOm CinstitNessuna valutazione finora

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Drug Benefit ListDocumento221 pagineDrug Benefit ListPharmaruthiNessuna valutazione finora

- PV in ThailandDocumento47 paginePV in Thailanddewi atmaja100% (1)

- Modern Trends in Hypnosis Ed by David Waxman & Prem C Misra & Michael Gibson & M Anthony Basker (1985)Documento404 pagineModern Trends in Hypnosis Ed by David Waxman & Prem C Misra & Michael Gibson & M Anthony Basker (1985)marcinlesniewicz100% (4)

- Type 2 Diabetes TreatmentDocumento2 pagineType 2 Diabetes TreatmentRatnaPrasadNalamNessuna valutazione finora

- Pediatric LeukemiasDocumento42 paginePediatric LeukemiasslyfoxkittyNessuna valutazione finora

- ResumeDocumento3 pagineResumeAstig Kuging63% (8)

- Oral Submucous Fibrosis Medical Management PDFDocumento8 pagineOral Submucous Fibrosis Medical Management PDFDame rohanaNessuna valutazione finora

- MHFW OrderDocumento4 pagineMHFW OrderNavjivan IndiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Sleep Gauge - Sleep Quality ScoreDocumento1 paginaSleep Gauge - Sleep Quality ScoreMike UyNessuna valutazione finora

- Neuropsychologia: Jade Dignam, David Copland, Alicia Rawlings, Kate O 'Brien, Penni Burfein, Amy D. RodriguezDocumento12 pagineNeuropsychologia: Jade Dignam, David Copland, Alicia Rawlings, Kate O 'Brien, Penni Burfein, Amy D. RodriguezFrancisco Beltrán NavarroNessuna valutazione finora

- MAN ParaTitle-Manuscript - Grace-EpresDocumento80 pagineMAN ParaTitle-Manuscript - Grace-EpresSevered AppleheadNessuna valutazione finora

- VAP in ChildrenDocumento19 pagineVAP in Childrensiekasmat upaNessuna valutazione finora

- Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic State (HHS)Documento21 pagineHyperosmolar Hyperglycemic State (HHS)Malueth AnguiNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 2. Theory and Practice of Counseling and Psychotherapy (Corey)Documento5 pagineChapter 2. Theory and Practice of Counseling and Psychotherapy (Corey)Angela Angela100% (1)

- Youstina Khalaf Exam 26-5Documento6 pagineYoustina Khalaf Exam 26-5M Usman KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- NBME Practice TestDocumento13 pagineNBME Practice TestZoë IndigoNessuna valutazione finora

- Peter Pan SyndromeDocumento4 paginePeter Pan SyndromeDaltry Gárate100% (2)

- Argos SBR: A Compact SBR System Offering Process Flexibility and Major Capital SavingsDocumento2 pagineArgos SBR: A Compact SBR System Offering Process Flexibility and Major Capital SavingsViorel HarceagNessuna valutazione finora

- Accuveinav400 For Vein Visualisation PDF 1763868852421Documento24 pagineAccuveinav400 For Vein Visualisation PDF 1763868852421Mohannad HamdNessuna valutazione finora

- UroflowDocumento41 pagineUroflowSri HariNessuna valutazione finora

- Cae Open Cloze PhobiasDocumento3 pagineCae Open Cloze PhobiasValéria DuczaNessuna valutazione finora

- ResumeDocumento4 pagineResumeapi-283952616Nessuna valutazione finora

- Medical Report For Foreign Worker Health ScreeningDocumento7 pagineMedical Report For Foreign Worker Health ScreeningP Venkata SureshNessuna valutazione finora

- Reading Activity ANDREA ALMENDARES 2DO PARCIALDocumento2 pagineReading Activity ANDREA ALMENDARES 2DO PARCIALAndrea Almendares Vasquez0% (1)

- StreptokinaseDocumento2 pagineStreptokinasePramod RawoolNessuna valutazione finora

- Desinfectants and AntisepticsDocumento14 pagineDesinfectants and AntisepticsAri Sri WulandariNessuna valutazione finora

- Basetext SingleDocumento129 pagineBasetext SingleJiHyun ParkNessuna valutazione finora

- 215 PDFDocumento7 pagine215 PDFlewamNessuna valutazione finora

- Massage Therapy PDFDocumento1 paginaMassage Therapy PDFVirgilio BernardinoNessuna valutazione finora

- PRICELIST OGB JKN Update 08.04.22Documento7 paginePRICELIST OGB JKN Update 08.04.22Imro FitrianiNessuna valutazione finora