Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Case of Del Rio Prada v. Spain

Caricato da

OceesCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Case of Del Rio Prada v. Spain

Caricato da

OceesCopyright:

Formati disponibili

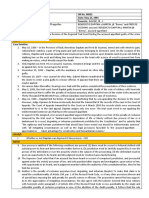

THIRD SECTION

CASE OF DEL RIO PRADA v. SPAIN

(Application no. 42750/09)

JUDGMENT

STRASBOURG

10 July 2012

THIS CASE WAS REFERRED TO THE GRAND CHAMBER

WHICH DELIVERED JUDGMENT IN THE CASE ON

21/10/2013

This judgment may be subject to editorial revision.

DEL RIO PRADA v. SPAIN JUDGMENT

In the case of Del Rio Prada v. Spain,

The European Court of Human Rights (Third Section), sitting as a

Chamber composed of:

Josep Casadevall, President,

Corneliu Brsan,

Alvina Gyulumyan,

Egbert Myjer,

Jn ikuta,

Luis Lpez Guerra,

Nona Tsotsoria, judges,

and also Santiago Quesada, Section Registrar,

After having deliberated in private on 26 June 2012,

Delivers the following judgment, which was adopted on that date:

PROCEDURE

1. The case originated in an application (no. 42750/09) against the

Kingdom of Spain lodged with the Court under Article 34 of the

Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms

(the Convention) by a Spanish national, Ms Ins Del Rio Prada (the

applicant), on 3 August 2009.

2. The applicant was represented by Mr D. Rouget and Mr I. Aramendia,

lawyers practising in Saint-Jean-de-Luz and Pamplona respectively. The

Spanish Government (the Government) were represented by their Agent,

Mr I. Blasco Lozano, Head of the Legal Department for Human Rights at

the Ministry of Justice.

3. The applicant alleged in particular that her continued detention from 3

July 2008 was neither lawful nor in accordance with a procedure

prescribed by law as required by Article 5 1 of the Convention. Relying

on Article 7, she complained about the retroactive application of new caselaw introduced by the Supreme Court after her conviction, which effectively

increased her sentence by almost nine years.

4. On 19 November 2009, the President of the Third Section decided to

communicate the application to the Government. It was also decided to rule

on the admissibility and merits of the application at the same time

(Article 29 1).

DEL RIO PRADA v. SPAIN JUDGMENT

THE FACTS

I. THE CIRCUMSTANCES OF THE CASE

5. The applicant was born in 1958. She is serving a prison sentence in

the region of Murcia (Spain).

6. In eight sets of criminal proceedings before the Audiencia Nacional,

the applicant was sentenced as follows:

- In judgment 77/1988 of 18 December 1988: for being a member of a

terrorist organisation, to eight years imprisonment; for illegal possession of

weapons, to seven years imprisonment; for possession of explosives, to

eight years imprisonment; for forgery, to four years imprisonment; for

using forged identity documents, to six months imprisonment.

- In judgment 8/1989 of 27 January 1989: for damage to property, in

conjunction with six counts of grievous bodily harm, one of causing bodily

harm and nine of causing minor injuries, to sixteen years imprisonment.

- In judgment 43/1989 of 22 April 1989: as a key accomplice in a fatal

attack and for murder, to twenty-nine years imprisonment.

- In judgment 54/1989 of 7 November 1989, as a key accomplice in a

fatal attack, to thirty years imprisonment; for eleven murders, to twentynine years for each murder; for seventy-eight attempted murders, to twentyfour years on each count; for damage to property, to eleven years

imprisonment. The court ordered that in application of Article 70 2 of the

Criminal Code of 1973 the maximum duration of the sentence to be served

(condena) should be thirty years.

- In judgment 58/1989 of 25 November 1989: as a key accomplice in a

fatal attack and in two murders, to twenty-nine years imprisonment in

respect of each charge. In keeping with Article 70 2 of the Criminal Code

of 1973, the court ordered that the maximum duration of the sentence to be

served (condena) should be thirty years.

- In judgment 75/1990 of 10 December 1990: for a fatal attack, to thirty

years imprisonment; for four murders, to thirty years imprisonment on

each count; for eleven attempted murders, to twenty years imprisonment on

each count; on the charge of terrorism, to eight years imprisonment. The

judgment indicated that in respect of the custodial sentences the maximum

sentence provided for in Article 70 2 of the Criminal Code of 1973 should

be taken into account.

- In judgment 29/1995 of 18 April 1995: for a fatal attack, to twenty-nine

years imprisonment; for murder, to twenty-nine years imprisonment. The

court again referred to the maximum term of imprisonment provided for in

Article 70 of the Criminal Code.

- In judgment 24/2000 of 8 May 2000: for an attack combined with

attempted murder, to thirty years imprisonment; for murder, to twenty-nine

years imprisonment; for seventeen attempted murders, to twenty-four

DEL RIO PRADA v. SPAIN JUDGMENT

years imprisonment on each count; and for damage to property, to eleven

years imprisonment. The judgment noted that the sentence served should

not exceed the maximum term provided for in Article 70 2 of the Criminal

Code of 1973. In order to determine which criminal law was applicable (the

Criminal Code of 1973, which was applicable at the material time, or the

later Criminal Code of 1995), the Audiencia Nacional considered that the

more lenient law was the 1973 Criminal Code, because of the maximum

term of sentence provided for in its Article 70 2, in conjunction with its

Article 100 (reduction of sentence for work done).

7. In all, the terms of imprisonment to which the applicant was

sentenced amounted to over 3,000 years.

8. The applicant was held in preventive detention from 6 July 1987 to 13

February 1989. On 14 February 1989 she began to serve her sentence after

conviction.

9. By a decision of 30 November 2000 the Audiencia Nacional notified

the applicant that the legal and chronological links between the crimes of

which she had been convicted made it possible to group them together as

provided for in Article 988 of the Code of Criminal Procedure in

conjunction with Article 70 2 of the 1973 Criminal Code, which had been

in force when the offences were committed. The Audiencia Nacional

combined all the applicants prison sentences together and fixed the total

term of imprisonment to be served at 30 years.

10. By a decision of 15 February 2001, the Audiencia Nacional fixed the

date on which the applicant would have fully discharged her sentence

(liquidacin de condena) at 27 June 2017.

11. On 24 April 2008 the authorities at the prison where the applicant

was serving her sentence decided that, taking into account the 3282 days

remission to which she was entitled for the work she had done since 1987,

she should be released on 2 July 2008.

12. On 19 May 2008 the Audiencia Nacional asked the prison authorities

to review the date of the applicants release in the light of new precedent set

by the Supreme Court in its judgment 197/06 of 28 February 2006, of which

the Audiencia Nacional cited the relevant parts (see Relevant domestic law

and practice, below), which stated, inter alia:

Thus, the execution of the total sentence to be served [condena] shall proceed as

follows: it shall begin with the heaviest sentences pronounced. The relevant benefits

and remissions shall be applied to each of the sentences being served. When the first

sentence has been served, the second sentence shall begin and so on, until the limits

provided for in Article 70 2 of the Criminal Code of 1973 have been reached. At

such time, all of the sentences comprised in the total sentence to be served [condena]

shall have been extinguished.

13. The Audiencia Nacional explained that this new case-law applied

only to those people convicted under the Criminal Code of 1973 to whom

DEL RIO PRADA v. SPAIN JUDGMENT

Article 70 2 had been applied. As that was the applicants case, the date of

her release would be changed accordingly.

14. The applicant lodged an appeal (splica). She argued, inter alia, that

the application of the Supreme Courts judgment was in breach of the

principle of non-retroactivity of criminal law provisions less favourable to

the accused. In her case the reduction of sentence for work done would now

be calculated for each individual sentence and not for the total sentence to

be served and up to the maximum limit of 30 years. This new method of

calculation would in effect increase the term of imprisonment actually

served by the applicant by almost nine years.

15. By an order of 23 June 2008 the Audiencia Nacional set the date for

the applicants release at 27 June 2017.

16. The applicant appealed against that decision.

17. By a decision of 10 July 2008 the Audiencia Nacional rejected the

appeal and noted that it was not a matter of limits on prison sentences, but

rather of how to apply reductions of sentence in order to determine the date

of the prisoners release. Such reductions were to be calculated in relation to

each sentence individually. Concerning the principle of non-retroactivity,

the Audiencia Nacional considered that it had not been breached because

the criminal law applied in this case had been in force at the time of its

application.

18. Relying on Articles 14 (prohibition of discrimination), 17 (right to

liberty), 24 (right to effective legal protection) and 25 (principle of legality)

of the Constitution, the applicant lodged an amparo appeal with the

Constitutional Court. By a decision of 17 February 2009, the Constitutional

Court declared the appeal inadmissible on the grounds that the applicant had

not demonstrated the constitutional relevance of her complaints.

II. RELEVANT DOMESTIC LAW AND PRACTICE

A. The Constitution

19. The relevant provisions of the Constitution read as follows:

Article 14

All Spaniards are equal before the law and may not in any way be discriminated

against on account of birth, race, sex, religion, opinion or any other personal or social

condition or circumstance.

Article 17

1. Every person has the right to liberty and security. No one may be deprived of

his or her freedom except in accordance with the provisions of this Article and in the

cases and in the manner prescribed by law.

...

DEL RIO PRADA v. SPAIN JUDGMENT

Article 24

1. All persons have the right to obtain the effective protection of the judges and the

courts in the exercise of their rights and legitimate interests, and in no case may there

be a lack of defence.

2. Likewise, all persons have the right of access to the ordinary judge predetermined

by law; to the defence and assistance of a lawyer; to be informed of the charges

brought against them; to a public trial without undue delays and with full guarantees;

to the use of evidence appropriate to their defence; not to make self-incriminating

statements; not to declare themselves guilty; and to be presumed innocent. ...

Article 25

1. No one may be convicted or sentenced for any act or omission which at the time

it was committed did not constitute a criminal offence, misdemeanour or

administrative offence under the law in force at that time.

...

B. The situation under the Criminal Code of 1973

20. The relevant provisions of the Criminal Code of 1973, as in force at

the material time, read as follows:

Article 70

When all or some of the sentences imposed ... cannot be served simultaneously by

a convict, the following rules shall apply:

1. In imposing the term to be served, the order followed shall be that of the severity

of the respective sentences, which the convict shall serve consecutively if possible,

going on to the next sentence when the previous one has been served or extinguished

by pardon ...

2. Notwithstanding the previous rule, the maximum term to be served (condena) by

a convict shall not exceed triple the time imposed for the most serious of the penalties

incurred, the others being declared extinguished once those already imposed cover

that maximum, which may not exceed thirty years.

The above limitation shall be applied even where the penalties have been imposed in

different proceedings, if the facts, because they are connected, could have been tried

as a single case.

Article 100

Once his judgment or conviction has become final, any person serving a custodial

or prison sentence may be granted a remission of sentence in exchange for work done.

In serving the sentence imposed ... the detainee is entitled to one days remission for

every two days worked, and the time thus deducted is taken into account when

granting release on licence.

The following persons shall not be entitled to remission for work done:

1. Detainees who escape or attempt to escape, even if they do not succeed.

2. Detainees who repeatedly misbehave while serving their sentence.

DEL RIO PRADA v. SPAIN JUDGMENT

21. The relevant provision of the Code of Criminal Procedure in force at

the material time reads a follows:

Article 988

... When a person found guilty of several criminal offences is convicted, in

different sets of proceedings, of offences that could have been tried in a single case, in

accordance with Article 17 of the Code, the judge or court which pronounced the last

judgment of conviction shall, of its own motion or at the request of the public

prosecutor or the convicted person, fix the maximum term to be served in respect of

the sentences pronounced, in keeping with Article 70 2 of the Criminal Code ...

22. The relevant section of the 1981 Prison Rules (no. 1201/1981)

explained as follows how to calculate the term of imprisonment (three

quarters of the sentence pronounced) to be served in order for the detainee

to be eligible for release on licence:

Article 59

In calculating three quarters of the sentence, the following rules shall apply:

(a) The part of the sentence to be served (condena) which is subject to pardon for

the purposes of release on licence shall be deducted from the total penalty

pronounced, as if that penalty has been replaced by a lesser one.

(b) The same rule shall apply to prison benefits entailing a reduction of the sentence

to be served (condena).

(c) When a person is sentenced to two or more custodial sentences, the sum of those

sentences, for the purposes of release on licence, shall be considered as a single

sentence to be served (condena). ...

C. The situation following the entry into force of the Criminal Code

of 1995

23. The new Criminal Code of 1995 did away with the reduction of

sentences in consideration of the work done in prison. However, those

prisoners whose conviction was pronounced on the basis of the Criminal

Code of 1973 even after the entry into force of the new Code continued

to be eligible for reductions of sentence for work done. As to the maximum

length of prison sentences and the application of reductions to the time

served, the Criminal Code of 1995 was amended by institutional law 7/2003

on measures for the full and effective execution of sentences. The relevant

parts of the Criminal Code thus amended read as follows:

Article 75 Order in which sentences are served

When some or all of the penalties for the different offences cannot be served

concurrently, they shall be served consecutively, in descending order of severity, as

far as possible.

DEL RIO PRADA v. SPAIN JUDGMENT

Article 76 Maximum legal term of imprisonment to be served

1. Notwithstanding what is set forth in the preceding Article, the maximum

duration of the sentence to be served (condena) by a convict shall not exceed triple the

time imposed for the most serious of the penalties incurred, the others being declared

extinguished once those already imposed cover that maximum, which may not exceed

twenty years. Exceptionally, the maximum limit shall be:

(a) Twenty-five years when an individual has been found guilty of two or more

crimes and one of them is punishable by law with a prison sentence of up to twenty

years;

(b) Thirty years when a convict has been found guilty of two or more crimes and

one of them is punishable by law with a prison sentence exceeding twenty years;

(c) Forty years when a convict has been found guilty of two or more crimes and at

least two of them are punishable by law with a prison sentence exceeding twenty

years;

(d) Forty years when a convict has been found guilty of two or more crimes ... of

terrorism ... and any of them is punishable by law with a prison sentence exceeding

twenty years.

2. The above limitation shall be applied even where the penalties have been imposed

in different proceedings, if the facts, because they are connected or because of when

they were committed, could have been tried as a single case.

Article 78 Prison benefits and calculation of time to be served prior to release on

licence in respect of all the penalties incurred

1. If, as a result of the limitations established in section 1 of Article 76, the

sentence to be served is less than half the aggregate of all the sentences imposed, the

sentencing judge or court may order that prison benefits, day-release permits, prerelease classification and the calculation of the time remaining to be served prior to

release on licence be determined with reference to all of the sentences pronounced.

2. Such a decision shall be mandatory in the cases referred to in paragraphs (a), (b),

(c) and (d) of section 1 of Article 76 of this Code, provided that the sentence to be

served is less than half the aggregate of all the sentences imposed. ...

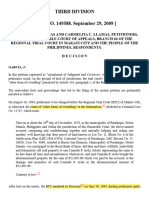

D. The case-law of the Supreme Court

24. In an order of 25 May 1990, the Supreme Court considered that the

combining of sentences in application of Article 70 2 of the Criminal

Code of 1973 and Article 988 of the Code of Criminal Procedure concerned

not the execution but the fixing of the sentence, and that its application

was accordingly a matter for the convicting judge, not the judge responsible

for the execution of sentences (Juzgados de Vigilancia Penitenciaria).

25. In a judgment of 8 March 1994 (529/1994) the Supreme Court

affirmed that the maximum term of imprisonment (thirty years) provided for

in Article 70 2 of the Criminal Code of 1973 was just like a new sentence

resulting from but independent of the others to which prison benefits

provided for by law, such as release on licence and remission of sentence,

applied (point 5 of the reasoning). The Supreme Court referred to Article

DEL RIO PRADA v. SPAIN JUDGMENT

59 of the Prison Rules of 1981, according to which the combining of two

custodial sentences into one was considered as a new sentence for the

purposes of the application of release on licence.

26. That approach continued to be adopted after the entry into force of

the Criminal Code of 1995 as regards the legal maximum term to be served

under Article 76 thereof (see paragraph 23 above). In its judgment

1003/2005, of 15 September 2005, the Supreme Court affirmed that this

limit is just like a new sentence resulting from but independent of the

others to which prison benefits provided by law, such as release on

licence, day release and pre-release classification apply (point 6 of the

reasoning). A similar approach was followed in the judgment of 14 October

2005 (1223/2005), in which the Supreme Court, in the same terms,

reiterated that the maximum term of imprisonment to be served is just like

a new sentence resulting from but independent of the others to which

prison benefits provided for by law, such as release on licence must be

applied, subject to the exceptions provided for in Article 78 of the Criminal

Code of 1995 (point 1 of the reasoning).

27. The Supreme Court departed from this case-law, however, in

judgment 197/2006, of 28 February 2006, in which it established what is

known as the Parot doctrine. The Supreme Court held that reductions of

prisoners sentences should be applied to each sentence individually, not to

the maximum sentence of thirty years imprisonment provided for in Article

70 2 of the Criminal Code of 1973. The relevant parts of the Supreme

Courts reasoning read as follows:

... a joint interpretation of rules one and two of Article 70 of the Criminal Code of

1973 leads us to consider that the thirty-year maximum term does not become a new

sentence, distinct from those successively imposed on the convict, or another sentence

resulting from all the previous ones, but is the maximum term of imprisonment a

prisoner should serve. The reasons that lead us to this interpretation are: (a) first, from

a purely literal point of view, the Criminal Code by no means considers the maximum

term of thirty years as a new sentence to which any reductions to which the prisoner is

entitled should apply, quite simply because it says no such thing; (b) on the contrary,

the penalty (pena) and the resulting term of imprisonment to be served (condena) are

two different things; the wording used in the Criminal Code refers to the resulting

limit as the maximum term to be served (condena), establishing the different

lengths of that maximum term to be served (condena) in relation to each of the

respective sentences imposed, and calculated in two different ways, by taking the

different sentences in order of gravity, in accordance with the first rule, until one of

the two maximum limits provided for is attained (three times the length of the heaviest

sentence pronounced or, in any event, no more than thirty years); (c) this

interpretation is also suggested by the wording of the Code, since after completing the

successive sentences as mentioned, the prisoner will stop discharging [that is,

serving] the remaining ones [in the prescribed order] as soon as the sentences already

served reach the requisite maximum length, which may on no account exceed thirty

years ... (e) and from a teleological point of view, it would not be logical, simply

because of the aggregation of sentences, for a copious criminal record to be reduced to

a single new sentence of thirty years, with the effect that an individual who has

committed a single offence is treated, without justification, in the same way as

DEL RIO PRADA v. SPAIN JUDGMENT

someone convicted of multiple offences, as is the case here. Indeed, there is no logic

in applying this rule in such a way that committing one murder is punished in the

same way as committing two hundred murders; (f) were application for a pardon to be

made, it could not apply to the resulting total term to be served (condena), but rather

to one, several or all of the different sentences imposed; in such a case it is for the

court that pronounced the sentence to decide, and not the judicial body responsible for

applying the limit (the last one), which shows that the sentences are different; and in

any event, the first rule of Article 70 of the Criminal Code of 1973 states how, in such

a case, to verify the successive completion of the sentences when the previous ones

have been extinguished by pardon; (g) and to conclude this reasoning, from a

procedural point of view Article 988 of the Code of Criminal Procedure clearly states

that it is a matter of fixing the maximum limit of the sentences pronounced (in the

plural, in keeping with the wording of the law), in order to determine the maximum

length of these sentences (the wording is very clear).

Which is why the term aggregate of the sentences to be served [condenas] is very

misleading and inappropriate. The sentences are not merged into one, but the serving

of multiple sentences is limited by law to a certain maximum term. Consequently, the

prisoner serves the different sentences, with their respective specificities and with all

the benefits to which he is entitled. That being so, for the extinction of the sentences

successively served, the reduction of sentences for work done may be applied in

conformity with Article 100 of the Criminal Code of 1973.

Thus, the method for the discharge of the total term to be served [condena] is as

follows: it begins with the heaviest sentences imposed. The relevant benefits and

remissions are applied to each of the sentences the prisoner is serving. When the first

[sentence] has been served, the prisoner begins to serve the next one and so on, until

the limits provided for in Article 70 2 of the Criminal Code of 1973 have been

reached. At this stage, all of the sentences comprised in the total term to be served

[condena] will have been extinguished.

For example, in the case of an individual given three prison sentences, 30 years, 15

years and 10 years. The second rule of Article 70 of the Criminal Code of 1973 ...

limits the actual term to be served to three times the most serious sentence or a

maximum of 30 years imprisonment. In this case, it would be the maximum term of

thirty years. The successive serving of the sentences (the total term to be served)

begins with the first sentence, which is the longest one (30 years in this case). If [the

prisoner] were granted a ten-year remission for whatever reason, he would have

served that sentence after 20 years imprisonment, and the sentence would be

extinguished; next, [the prisoner] would start to serve the next longest sentence (15

years), and with a remission of 5 years that sentence will have been served after 10

years. 20 + 10 = 30. [The prisoner] would not have to serve any other sentence, any

remaining sentences being extinguished, as provided for in the applicable Criminal

Code, once those already imposed cover that maximum, which may not exceed thirty

years.

28. In that judgment the Supreme Court considered that there was no

well-established case-law on the specific question of the interpretation of

Article 100 of the Criminal Code of 1973 in relation to Article 70 2. It

referred to a single precedent, its judgment of 8 March 1994 in which it

considered that the maximum duration provided for in Article 70 2 of the

Criminal Code of 1973 was just like a new, independent sentence (see

paragraph 25 above). However, the Supreme Court departed from that

10

DEL RIO PRADA v. SPAIN JUDGMENT

interpretation, pointing out that that decision, which it considered an

isolated one, could not be relied on as a precedent in so far as it had never

been applied in a constant manner as required under Article 1 6 of the

Civil Code. Even assuming that that decision could have been considered as

a precedent, the court reiterated that the principle of equality before the law

(Article 14 of the Constitution) did not preclude departures from the caselaw, provided that sufficient reasons were given. Furthermore, the principle

that the law should not be applied retroactively (Article 25 1 of the

Constitution) was not meant to apply to case-law.

29. A dissenting opinion was appended to judgment 197/2006 by three

judges. They considered that the sentences imposed successively were

transformed or combined into another sentence of the same kind, but

different in so far as it combined the various sentences into one. They called

it the sentence to be served, that is to say the one resulting from the

application of the limit fixed in Article 70 2 of the Criminal Code of 1973,

which effectively extinguished the sentences that went beyond that limit.

This new unit of punishment was the term the prisoner had to serve, to

which remission for work done should be applied. Remissions should

therefore be applied to the sentences imposed, but only once they had been

processed in conformity with the rules on the consecutive serving of

sentences. The dissenting judges also pointed out that for the purposes of

determining the most lenient criminal law following the entry into force of

the Criminal Code of 1995, all Spanish courts, including the Supreme Court

(agreements adopted at the Plenary sessions on 18 July 1996 and 12

February 1999), had agreed to the principle that reductions of sentence

should be applied to the sentence resulting from the application of Article

70 2 of the Criminal Code of 1973 (the thirty-year limit). In application of

that criterion no fewer than sixteen people convicted of terrorism had

recently had their sentences reduced for work done although they had each

been given prison sentences of over a hundred years.

30. The dissenting judges considered that the method applied by the

majority was not provided for in the Criminal Code of 1973 and therefore

amounted to retroactive implicit application of the new Article 78 of the

Criminal Code of 1995, as modified by institutional law 7/2003 on

measures for the full and effective execution of sentences (see paragraph 23

above). This new interpretation was also contra reo, constituted a policy of

full execution of sentences alien to the Criminal Code of 1973, could be a

source of inequalities and was contrary to the case-law of the Supreme

Court (judgments of 8 March 1994, 15 September 2005 and 14 October

2005, see paragraphs 25-26 above). Lastly, the dissenting judges considered

that criminal policy reasons could on no account justify such a departure

from the principle of legality, even in the case of an unrepentant terrorist

murderer.

DEL RIO PRADA v. SPAIN JUDGMENT

11

E. Recent developments: the case-law of the Constitutional Court

31. In a series of judgments of 29 March 2012 the Constitutional Court

ruled on several amparo appeals lodged by convicts to whom the Parot

doctrine had been applied. In two cases (4893-2006, 4793-2009) it allowed

the appeals for violation of the right to effective judicial protection

(Article 24 1 of the Constitution) and the right to liberty (Article 17 1 of

the Constitution). The Constitutional Court considered that the new method

of calculating remission following the Supreme Courts departure in 2006

from its earlier case-law was in contradiction with the earlier final judicial

decisions in the appellants cases. In those earlier firm and final decisions,

in order to determine which was the most lenient criminal law applicable

(the Criminal Code of 1973 or that of 1995), the courts had based

themselves on the principle that the reductions of sentence for work done

provided for in the Criminal Code of 1973 should be applied to the thirtyyear maximum sentence, not to each sentence individually. In so doing they

had reached the conclusion that the regime of the Criminal Code of 1973,

with its reductions of sentence for work done, was more favourable to the

appellants than the new Criminal Code of 1995. In a third case (appeal no.

10651-2009), the Constitutional Court found in the appellants favour for

violation of the right to effective judicial protection (Article 24 of the

Constitution), considering that the Audiencia Nacional had changed the date

of the prisoners final release, thereby disregarding its own firm and final

judicial decision given a few days earlier. In these three cases the

Constitutional Court pointed out that the right to effective judicial

protection included the right not to have final judicial decisions overruled

(the intangibility of final judicial decisions).

32. In twenty-five other cases the Constitutional Court dismissed the

amparo appeals on the merits, finding that the decisions by which the

ordinary courts had set the appellants final dates of release in application of

the departure from precedent in 2006 had not contravened any final judicial

decision concerning them.

33. Both in the judgments in the appellants favour (paragraph 31) and

in those against them (paragraph 32) the Constitutional Court dismissed the

complaints under Article 25 of the Constitution (principle of legality),

considering that the question of the calculation of remission for work done

concerned the execution of the sentence and on no account the application

of a harsher sentence than that provided for in the applicable criminal law,

or a sentence exceeding the limit allowed by law. It cited the case-law of the

European Court of Human Rights according to which a distinction was to be

made, for the purposes of Article 7 of the Convention, between measures

constituting a penalty and measures relating to the execution of a

penalty (Grava v. Italy, no. 43522/98, 51, 10 July 2003, and Gurguchiani

v. Spain, no. 16012/06, 31, 15 December 2009).

12

DEL RIO PRADA v. SPAIN JUDGMENT

34. Several judges appended separate concurring or dissenting opinions

to the judgments of the Constitutional Court.

THE LAW

I. ALLEGED VIOLATION OF ARTICLE 7 OF THE CONVENTION

35. The applicant complained about the retroactive application of the

Supreme Courts case-law to her case. She reiterated that the prison in

Murcia where she was incarcerated had already fixed the date of her release

in application of Article 70 2 of the Criminal Code, and stressed that the

new calculation had increased her detention by almost nine years. She relied

on Article 7 of the Convention, which reads as follows:

1. No one shall be held guilty of any criminal offence on account of any act or

omission which did not constitute a criminal offence under national or international

law at the time when it was committed. Nor shall a heavier penalty be imposed than

the one that was applicable at the time the criminal offence was committed.

2. This Article shall not prejudice the trial and punishment of any person for any act

or omission which, at the time when it was committed, was criminal according to the

general principles of law recognised by civilised nations.

A. Admissibility

36. The Government submitted that Article 7 did not concern the

provisions governing the calculation of prison benefits leading to a

reduction of sentence, but only those relating to crimes and their

punishment. They relied on 142 of the Kafkaris v. Cyprus [GC] judgment

(no. 21906/04, 12 February 2008), concerning the distinction between a

measure which constituted a penalty and one concerning the

execution or application thereof. In the instant case the sentences

imposed added up to over 3,000 years imprisonment and were to be served

consecutively up to the maximum limit of thirty years. Unlike in the

Kafkaris case, in the present case the borderline between sentence and

execution of sentence was very clear. The method for calculating prison

benefits to earn a reduction of the sentences imposed was not part of the

penalty within the meaning of Article 7.

37. The applicant submitted that in applying the Supreme Courts newly

introduced case-law in its judgment 197/2006, the Audiencia Nacional had

considerably increased the length of her detention, by pushing back the date

of her release from 2 July 2008, as fixed by the prison authorities, to

27 June 2017, that is, by an additional nine years. The aggravation of the

applicants penalty, increasing the term of her detention by over nine years,

DEL RIO PRADA v. SPAIN JUDGMENT

13

was serious, and in terms of its length and its consequences went well

beyond the mere execution of the penalty. For the applicant, it in fact

amounted to the imposition of a heavier penalty.

38. The Court considers that this question is closely linked to the

substance of the applicants complaint under Article 7 of the Convention,

and decides to join it to the merits (see, mutatis mutandis, Gurguchiani v.

Spain, no. 16012/06, 25, 15 December 2009). It notes that this complaint

is not manifestly ill-founded within the meaning of Article 35 3 (a) of the

Convention or inadmissible on any other grounds. It must therefore be

declared admissible.

B. The merits

1. The parties submissions

39. The applicant alleged that the new method for calculating reductions

of sentence had been applied without any change to the relevant legal

provisions, by a simple departure from precedent by the Supreme Court

because of political and media pressure on it. There had accordingly been a

violation of Article 7 as regards the quality of the law. The applicant

referred to paragraph 152 of the above-mentioned Kafkaris judgment in this

connection.

40. She further submitted that a penalty harsher than that applicable at

the time when she had committed the offence for which she had been

convicted had been applied retroactively. Indeed, the resulting increase in

the term of imprisonment she was required to serve had deprived her of the

remission of sentence to which she was entitled.

41. The Government submitted that the offences and the penalties that

were applied to the applicant had been clearly defined in the Criminal Code

of 1973, well before the offences had been committed. All the convictions

pronounced by the Audiencia Nacional had therefore had a legal basis in the

Criminal Code in force at the time when the offences were committed. In

addition, the provisions concerning the execution of the different prison

sentences pronounced against the applicant, namely Articles 70 and 100 of

the Criminal Code of 1973, had also been in force at the material time. The

Government admitted, however, that prior to the Supreme Court judgment

197/2006 it was the practice of the prisons and the courts to consider the 30year limit established in Article 70 2 of the Criminal Code of 1973 as a

sort of new, independent sentence, to which prison benefits should be

applied.

42. The Government reiterated that the calculation of prison benefits fell

outside the scope of Article 7. Even assuming that it did fall within the

scope of Article 7, the legislative provisions governing prison benefits had

not changed. It was only the courts interpretation of them that had changed.

14

DEL RIO PRADA v. SPAIN JUDGMENT

In this connection the Government pointed out that according to the Courts

case-law Article 7 could not be read as outlawing the gradual clarification of

the rules of criminal liability through judicial interpretation from case to

case (Streletz, Kessler and Krenz v. Germany [GC], nos. 34044/96,

35532/97 and 44801/98, 50, ECHR 2001-II, and Kafkaris, cited above,

141). So surely a simple change in the case-law concerning the calculation

of prison benefits which, according to the Government affected neither the

definition of the offence nor the penalty imposed could not possibly

constitute a violation of Article 7. To claim otherwise would petrify the law

and make it impossible for the courts, through their case-law, to accomplish

their task of allowing the progressive development of criminal law. For

the Government, it was unthinkable that Article 7 should be seen as giving

all convicts the right to expect that from the time when the offence was

committed to the time when the sentence was fully discharged the case-law

concerning the calculation of prison benefits would never change.

43. The Government argued that the difficulty in proving what the

predominant interpretation was at the time was also apparent in the fact that

the Supreme Courts judgment 197/2006 cited a single precedent in the

matter (the judgment of 8 March 1994). The Supreme Court explicitly

departed from that precedent, in a reasoned and reasonable manner. The

departure from precedent was foreseeable because of the legal provisions

applied, which clearly stated that remission for work done was calculated in

respect of each sentence until the legal maximum was reached. Moreover,

by the time the prison had to calculate the reductions applicable to the

numerous sentences imposed on the applicant, a precedent had already been

clearly set in judgment 197/2006. However, the prison authorities did not

take that precedent into account in their initial proposal, which led the court

responsible for the execution of sentences the Audiencia Nacional to ask

them to make a new proposal, more in keeping with the established caselaw.

44. Lastly, according to the Government it could not be said that the

applicant had no way of knowing that she would be obliged to serve her

prison sentences up to the legal maximum of thirty years, as she had

constantly been reminded of that fact in the different judgments convicting

her, as well as in the decision of the Audiencia Nacional of 30 November

2000.

2. The Courts assessment

a) Summary of the relevant principles

45. The Court first recalls that the guarantee enshrined in Article 7,

which is an essential element of the rule of law, occupies a prominent place

in the Convention system of protection, as is underlined by the fact that no

derogation from it is permissible under Article 15 even in time of war or

DEL RIO PRADA v. SPAIN JUDGMENT

15

other public emergency. It should be construed and applied, as follows from

its object and purpose, in such a way as to provide effective safeguards

against arbitrary prosecution, conviction and punishment (see S.W. v. the

United Kingdom, 22 November 1995, 35, Series A no. 335-B).

46. The Court also reiterates that according to its case-law Article 7 of

the Convention is not confined to prohibiting the retrospective application

of the criminal law to an accuseds disadvantage. It also embodies, more

generally, the principle that only the law can define a crime and prescribe a

penalty (nullum crimen, nulla poena sine lege) (see Kokkinakis v. Greece,

25 May 1993, 52, Series A no. 260-A), as well as the principle that the

criminal law must not be extensively construed to an accuseds detriment,

for instance by analogy (see Come and Others v. Belgium, nos. 32492/96,

32547/96, 32548/96, 33209/96 and 33210/96, 145, ECHR 2000-VII, and

Kafkaris v. Cyprus [GC], no. 21906/04, 138, ECHR 2008-...). The result is

that an offence and the penalty incurred for it must be clearly defined by

law. This condition is fulfilled when the individual can tell from the

wording of the relevant provision and, if need be, with the assistance of the

courts interpretation of it, what acts and omissions will make him

criminally liable and what penalty will be imposed for the act committed

and/or omission (see Cantoni v. France, 15 November 1996, 29, Reports

of Judgments and Decisions 1996-V, and Kafkaris, cited above, 140).

Furthermore, the foreseeability of the law does not rule out the person

concerned having to take appropriate legal advice to assess, to a degree that

is reasonable in the circumstances, the consequences which a given action

may entail (see, among other authorities, Cantoni, cited above, 35).

47. The Court has acknowledged in its case-law that however clearly

drafted a legal provision may be, in any system of law, including criminal

law, there is an inevitable element of judicial interpretation. There will

always be a need for elucidation of doubtful points and for adaptation to

changing circumstances. Again, whilst certainty is highly desirable, it may

bring in its train excessive rigidity and the law must be able to keep pace

with changing circumstances. Accordingly, many laws are inevitably

couched in terms which, to a greater or lesser extent, are vague and whose

interpretation and application are questions of practice (see, mutatis

mutandis, Kokkinakis, cited above, 40). The role of adjudication vested in

the courts is precisely to dissipate such interpretational doubts as remain

(see, mutatis mutandis, Cantoni, cited above). Article 7 of the Convention

cannot be read as outlawing the gradual clarification of the rules of criminal

liability through judicial interpretation from case to case, provided that the

resultant development is consistent with the essence of the offence and

could reasonably be foreseen (see S.W. v. the United Kingdom, cited above,

36, and Streletz, Kessler and Krenz v. Germany [GC], nos. 34044/96,

35532/97 and 44801/98, 50, ECHR 2001-II).

16

DEL RIO PRADA v. SPAIN JUDGMENT

48. The concept of a "penalty" in Article 7 is, like the notions of "civil

rights and obligations" and "criminal charge" in Article 6 1, an

autonomous Convention concept. To render the protection offered by

Article 7 effective, the Court must remain free to go behind appearances and

assess for itself whether a particular measure amounts in substance to a

"penalty" within the meaning of this provision (see Welch v. the United

Kingdom, 9 February 1995, 27, Series A no. 307-A, and Jamil v. France,

8 June 1995, 30, Series A no. 317-B). The wording of Article 7 1,

second sentence, indicates that the starting-point in any assessment of the

existence of a penalty is whether the measure in question is imposed

following conviction for a criminal offence. Other factors that may be

taken into account as relevant in this connection are the nature and purpose

of the measure in question; its characterisation under national law; the

procedures involved in the making and implementation of the measure; and

its severity (see Welch, cited above, 28, and Jamil, cited above, 31). To

this end, both the Commission and the Court in their case-law have drawn a

distinction between a measure that constitutes in substance a penalty and

a measure that concerns the execution or enforcement of the penalty.

In consequence, where the nature and purpose of a measure relate to the

remission of a sentence or a change in a regime for early release, this does

not form part of the penalty within the meaning of Article 7 (see, among

other authorities, Hosein v. the United Kingdom, no. 26293/95, Commission

decision of 28 February 1996; Grava v. Italy, no. 43522/98, 51, 10 July

2003; Kafkaris, cited above, 142; Scoppola v. Italy (no. 2) [GC], no.

10249/03, 98, 17 September 2009; and M. v. Germany, no. 19359/04,

121, 17 December 2009). However, in practice, the distinction between the

two may not always be clear-cut (see Kafkaris, cited above, 142, and

Gurguchiani, cited above, 31).

b) Application of the above principles to the instant case

49. In the instant case the Court notes first of all that the applicants

convictions and the different prison sentences she was given had a legal

basis in the criminal law applicable at the material time, a fact which the

applicant does not dispute.

50. The parties arguments mainly concern the calculation of the total

sentence to be served in application of the rules on combined sentences, for

the purposes of applying the relevant remissions. In this connection the

Court notes that a decision of the Audiencia Nacional of 30 November 2000

fixed the maximum term of imprisonment to be served by the applicant in

order to discharge all the sentences pronounced against her at thirty years, in

accordance with Article 988 of the Code of Criminal Procedure and Article

70 2 of the Criminal Code of 1973, in force at the time when the offences

were committed. On 24 April 2008 the prison authorities set 2 July 2008 as

the date for the applicants release, a date arrived at by applying the

DEL RIO PRADA v. SPAIN JUDGMENT

17

remission for work done to which she was entitled to the maximum term of

thirty years imprisonment. Subsequently, on 19 May 2008, the Audiencia

Nacional asked the prison authorities to change the proposed date of release

and calculate a new date based on the new precedent set by the Supreme

Court in it judgment 197/06 of 28 February 2006. According to the new

precedent, the prison benefits and remissions to which the applicant was

entitled were to be applied to each of the sentences individually and not to

the thirty-year maximum term. Applying the new criterion, the Audiencia

Nacional fixed the new date of the applicants final release at 27 June 2017.

51. Consequently, the issue that the Court needs to determine in the

present case is what the penalty imposed on the applicant actually entailed

under the domestic law. The Court must, in particular, ascertain whether the

text of the law, read in the light of the accompanying interpretative caselaw, satisfied the requirements of accessibility and foreseeability. In doing

so it must have regard to the domestic law as a whole and the way it was

applied at the material time (see Kafkaris, cited above, 145).

52. It is true that when the applicant committed the offences, Article

70 2 of the Criminal Code of 1973 referred to a limit of thirty years

imprisonment as the maximum term or sentence to be served (condena) in

the event of multiple sentences. There thus seemed to be a distinction

between the concept of sentence to be served (condena) and the

sentences actually pronounced or imposed, that is to say the individual

sentences pronounced in the different judgments convicting the applicant.

Article 100 of the Criminal Code of 1973, on reduction of sentence for work

done, established that, in discharging the sentence imposed, the detainee

was entitled to one days remission for every two days work done.

However, that Article contained no specific guidance on calculating

reductions of sentence when the multiple sentences pronounced added up to

far more than the thirty-year limit provided for in Article 70 2 of the

Criminal Code, as they did in the applicants case (where they totalled over

3,000 years). Article 100 ruled out the application of reductions of sentence

for work done in only two specific cases: when detainees escaped or

attempted to escape, even if they did not succeed, and when they repeatedly

misbehaved while serving their sentence (see paragraph 20 above). The

Court observes that it was not until the entry into force of the new Criminal

Code of 1995 that the law made express provision for the possibility of

applying prison benefits to all the sentences imposed, not to the maximum

term to be served by law, and only in exceptional cases (Article 78 of the

Criminal Code, see paragraph 23 above).

53. The Court must also consider the case-law and practice regarding the

interpretation of the relevant provisions of the Criminal Code of 1973. It

notes, and the Government admit, that when a person was convicted and

sentenced to more than one term of imprisonment, the prison authorities,

with the agreement of the judicial authorities, generally considered that the

18

DEL RIO PRADA v. SPAIN JUDGMENT

limit provided for in Article 70 2 of the Criminal Code of 1973 (thirty

years imprisonment) became a sort of new, independent sentence to which

prison benefits should be applied (see paragraph 41 above). The prison

authorities thus took the approach that reductions of sentence should be

determined with reference to this maximum term of thirty years. This

approach is also found in the Supreme Courts judgment of 8 March 1994

(see paragraph 25 above), which was the Supreme Courts first ruling on the

subject, as well as in the practice of the Spanish courts when called upon to

determine which was the most lenient criminal law following the entry into

force of the Criminal Code of 1995, as pointed out by the dissenting judges

in the Supreme Courts judgment 197/2006 (see paragraph 29 above).

Indeed, this approach was applied to numerous prisoners in situations

similar to that of the applicant, having been convicted under the Criminal

Code of 1973, whose remissions for work done were deducted from the

maximum term of thirty years imprisonment (see paragraph 29 above).

54. The Court considers that in spite of the ambiguity of the applicable

provisions of the Criminal Code of 1973 and the fact that the first

clarification was not made by the Supreme Court until 1994, the practice

adopted by the prison authorities and the Spanish courts was to consider the

30-year maximum term of imprisonment to be served (condena) under

Article 70 2 of the Criminal Code of 1973 as a new, independent sentence,

to which certain prison benefits, such as reductions of sentence for work

done, should be applied. That practice gave the applicant a legitimate

expectation while serving her prison sentence, particularly after the

decisions of the Audiencia Nacional of 30 November 2000 (grouping the

sentences together) and 15 February 2001 (setting 27 June 2017 as the date

for her release), that the reductions of sentence to which she was entitled for

the work done since 1987 would be applied to the maximum legal term of

thirty years.

55. That being so, the Court accepts that at the time when the applicant

committed the offences, but also at the time when the decision to combine

the sentences was pronounced, the relevant Spanish law, taken as a whole,

including the case-law, was formulated with sufficient precision to enable

the applicant to discern, even with appropriate advice, to a degree that was

reasonable in the circumstances, the scope of the penalty imposed and the

manner of its execution (contrast Kafkaris, 150).

56. However, in its decisions of 19 May 2008 and 23 June 2008 the

Audiencia Nacional changed the date of the applicants early release from

the one fixed by the prison authorities, namely 2 July 2008. In so doing, the

Audiencia Nacional based itself on the new case-law established by the

Supreme Court in its judgment 197/06, of 28 February 2006 (see paragraphs

27 and 28 above), which was pronounced long after the applicant had

committed the offences and the decision to combine the sentences had been

taken. The Court notes that in this new judgment the Supreme Court

DEL RIO PRADA v. SPAIN JUDGMENT

19

departed, by a majority, from the precedent it had set in 1994. For the

majority of the judges the new method of calculating remission was more

consistent with the actual wording of the provisions of the Criminal Code of

1973, which made a distinction between penalties imposed and sentence

to be served (condena).

57. While the Court readily accepts that the domestic courts are the best

placed to interpret and apply domestic law, it also reiterates that the

principle, embodied in Article 7 de la Convention, that only the law can

define a crime and prescribe a penalty means that criminal law must not be

extensively construed to the detriment of the accused (see, for example,

Come and Others v. Belgium, ECHR 2000-VII, 145).

58. The Court notes that the new interpretation of the Supreme Court, as

applied in the present case, led to the sentence the applicant was to serve

being extended retroactively by almost nine years, in so far as all the

remission to which she was entitled for work done was lost because of the

length of the sentences pronounced against her. In such circumstances, even

if the Court accepts the Governments argument that the calculation of

remission as such falls outside the scope of Article 7, the way in which the

provisions of the Criminal Code of 1973 were applied went beyond this. As

the change of method used to calculate the sentence to be served had a

significant impact on the effective length of the sentence, to the applicants

detriment, the Court considers that the distinction between the scope of the

sentence imposed on the applicant and the manner of its execution was not

immediately apparent (see, mutatis mutandis, Kafkaris, cited above, 148).

59. Having regard to the above and in the light of Spanish law taken as a

whole, the Court considers that the new means of calculating remission,

based on the Supreme Courts departure from precedent, did not only

concern the execution of the applicants sentence. The measure also had a

decisive impact on the scope of the sentence imposed, leading in practice to

an increase of almost nine years in the term the applicant had to serve.

60. It remains to be seen whether this interpretation by the domestic

courts which came about long after the applicant committed the offences

for which she was convicted, and even after the decision of 30 November

2000 grouping the sentences together could reasonably have been foreseen

by the applicant (see S.W. v. the United Kingdom, cited above, 36). The

Court considers it necessary, in order to ensure that the protection afforded

by Article 7 1 of the Convention remains effective, to examine whether

the applicant could, if necessary after having consulted a lawyer, have

foreseen that once the court had ordered the sentences to be combined, the

domestic courts would adopt such an interpretation of the scope of the

penalty imposed, having regard in particular to the judicial and

administrative practice prior to the judgment of 28 February 2006 (see

paragraph 54 above). In this respect the Court notes that the only relevant

precedent cited in that judgment was that of 8 March 1994, in which the

20

DEL RIO PRADA v. SPAIN JUDGMENT

Supreme Court had taken the opposite approach, referring to Article 59 of

the Prison Rules of 1981 in force at the time the applicant committed the

offences. Furthermore, as the dissenting judges pointed out in the judgment

of 25 February 2006, the other judgments cited, even though they applied

the new Criminal Code of 1995, took a similar approach in considering the

maximum legal term of imprisonment as a new, independent sentence (see

paragraphs 26 and 30 above).

61. The Court notes that the lack of established case-law to support the

Supreme Courts judgment of 28 February 2006 is also reflected in the lack

of precedents supplied by the Government, who agree that the practice of

the prisons and the courts until that time had been in keeping with the

judgment of 8 March 1994, that is, more favourable to the applicant (see

paragraph 41 above).

62. The Court also notes that the Supreme Courts new case-law

deprived of all meaning the remissions of sentence to which individuals

convicted, like the applicant, under the old Criminal Code of 1973 were

entitled in exchange for work done, after having served a substantial part of

their sentences. In other words, the sentence the applicant was required to

serve was increased to 30 years effective imprisonment, on which the

applicable remission to which she would previously have been entitled had

no effect whatsoever. The Court observes that this change of case-law came

about after the entry into force of the new Criminal Code of 1995, which did

away with the system of reductions of sentence in exchange for work done

(see paragraph 23 above) and introduced new, stricter rules on the

calculation of remissions of sentence for offenders sentenced to multiple

lengthy terms of imprisonment (see paragraph 23 above, Article 78 of the

Criminal Code of 1995 as amended by institutional law 7/2003). While the

Court accepts that the States are free to amend their criminal policy,

including by increasing the penalties applicable for criminal offences (see

Achour v. France [GC], no. 67335/01, 44, ECHR 2006-IV), it considers

that the domestic courts must not, retroactively and to the detriment of the

individual concerned, apply the spirit of legislative changes brought in after

the offence was committed. The retroactive application of later criminal

laws is permitted only when the change of law is more favourable to the

accused (see Scoppola v. Italy (no. 2) [GC], no. 10249/03, 17 September

2009).

63. In the light of the above the Court considers that it was difficult, or

even impossible, for the applicant to foresee the Supreme Courts departure

from precedent and therefore to know, at the material time and also at the

time when all the sentences were combined into one, that the Audiencia

Nacional would calculate the reductions of sentence in respect of each

sentence individually and not of the total term to be served, thereby

substantially lengthening the time she would actually serve.

DEL RIO PRADA v. SPAIN JUDGMENT

21

64. That being so, the Court must reject the Governments preliminary

objection and conclude that there has been a violation of Article 7 of the

Convention.

II. ALLEGED VIOLATION OF ARTICLE 5 OF THE CONVENTION

65. The applicant considered that the fact that she was kept in detention

after 3 July 2008 was contrary to the requirements of lawfulness and

observance of a procedure prescribed by law. She relied on Article 5 of

the Convention, the relevant parts of which read as follows:

1. Everyone has the right to liberty and security of person. No one shall be

deprived of his liberty save in the following cases and in accordance with a procedure

prescribed by law:

(a) the lawful detention of a person after conviction by a competent court;

...

A. Admissibility

66. The Court notes that this complaint is not manifestly ill-founded

within the meaning of Article 35 3 (a) of the Convention and that it is not

inadmissible on any other grounds. It must therefore be declared admissible.

B. Merits

1. The parties submissions

67. The applicant submitted that following the Supreme Courts

departure from precedent, the length of her detention had been arbitrarily

extended until 27 June 2017, an increase of approximately nine years

compared with the date on which she should have been released by law. So

since 3 July 2008 she could not be considered to have been lawfully

detained in accordance with a procedure prescribed by law.

68. The Government replied that the applicant had been deprived of her

liberty by virtue of the different judgments by which the Audiencia

Nacional had convicted her, sentencing her to a total of more than 3,000

years imprisonment. It had therefore been clear to the applicant that she

would have to serve the different custodial sentences consecutively, up to

the legal limit of thirty years imprisonment, that is, until 7 July 2017. The

Government considered that the applicable legal provisions had been

sufficiently clear and precise to meet the required standards of quality of

law. Relying on the Kafkaris judgment, cited above, 120-121, they

maintained that the fact that the prison authorities had proposed a certain

date for the applicants final release (2 July 2008) could not possibly have

any incidence on the judgments by which she had been sentenced to over

22

DEL RIO PRADA v. SPAIN JUDGMENT

3,000 years imprisonment. Furthermore, unlike in the Kafkaris case, the

prison authorities had merely made a proposal, which the Audiencia

Nacional declined to accept because it went against the case-law of the

Supreme Court.

2. The Courts assessment

69. The Court reiterates, concerning the lawfulness of detention,

including the question whether "a procedure prescribed by law" has been

followed, that the Convention refers essentially to national law and lays

down the obligation to conform to the substantive and procedural rules of

national law. This primarily requires any arrest or detention to have a legal

basis in domestic law but also relates to the quality of the law, requiring it to

be compatible with the rule of law, a concept inherent in all the Articles of

the Convention see (Kafkaris, cited above, 116, and M. v. Germany,

no. 19359/04, 90, ECHR 2009). The quality of the law in this sense

implies that where a national law authorises deprivation of liberty it must be

sufficiently accessible, precise and foreseeable in its application, in order to

avoid all risk of arbitrariness (see Amuur v. France, 25 June 1996, 50,

Reports 1996-III). The standard of lawfulness set by the Convention thus

requires that all law be sufficiently precise to allow the person if need be,

with appropriate advice to foresee, to a degree that is reasonable in the

circumstances, the consequences which a given action may entail (see M. v.

Germany, cited above, 90, and Oshurko v. Ukraine, no. 33108/05, 98, 8

September 2011).

70. The "lawfulness" required by the Convention presupposes not only

conformity with domestic law but also, as confirmed by Article 18,

conformity with the purposes of the deprivation of liberty permitted by subparagraph (a) of Article 5 paragraph 1 (see Bozano v. France, judgment of

18 December 1986, 54, Series A no. 111, and Weeks v. the United

Kingdom, judgment of 2 March 1987, 42, Series A no. 114). Furthermore,

the word "after" in sub-paragraph (a) does not simply mean that the

detention must follow the "conviction" in point of time: in addition, the

"detention" must result from, "follow and depend upon" or occur "by virtue

of" the "conviction". In short, there must be a sufficient causal connection

between the conviction and the deprivation of liberty (see Weeks, cited

above, 42; Stafford v. the United Kingdom [GC], no. 46295/99, 64,

ECHR 2002-IV; Kafkaris, cited above, 117; and M. v. Germany, cited

above, 88).

71. The Court reiterates that even if Article 5 1 (a) of the Convention

does not guarantee, as such, a prisoners right to early release, be it

conditional or final (see rfan Kalan v. Turkey (dec.), no. 73561/01,

2 October 2001, and elikkaya v. Turkey (dec.), no. 34026/03, 1 June 2010),

the situation may differ when the domestic courts, having no discretionary

power, are obliged to apply such a measure to any individual who meets the

DEL RIO PRADA v. SPAIN JUDGMENT

23

conditions of entitlement laid down by law (see Grava v. Italy,

no. 43522/98, 43, 10 July 2003, and Pilla v. Italy, no. 64088/00, 41,

2 March 2006).

72. The Court has no doubt that the applicant was convicted by a

competent court, in accordance with a procedure prescribed by law, within

the meaning of Article 5 1 (a) of the Convention. Indeed, the applicant did

not challenge the lawfulness of her detention prior to 2 July 2008, the date

initially proposed by the prison for her final release. The question is rather

whether her detention after that date was in conformity with the penalty

initially imposed.

73. The Court notes that in eight different sets of proceedings the

applicant was found guilty by the Audiencia Nacional of several offences

linked to terrorist attacks. The sum total of all the custodial sentences

pronounced against her by virtue of the applicable provisions of the

Criminal Code amounted to over 3,000 years imprisonment. However, in

most of the judgments by which she was convicted, and in the decision of

30 November 2000 to combine the sentences, the Audiencia Nacional

indicated that the maximum term of imprisonment to be served, in

conformity with Article 70 2 of the Criminal Code of 1973, was thirty

years. The applicant was therefore detained by virtue of all the criminal

convictions pronounced against her by the Audiencia Nacional (see, mutatis

mutandis, Garagin v. Italy (dec.), no. 33290/07, 29 April 2008).

74. The Court must also verify that the effective duration of the

deprivation of liberty, taking account of the applicable rules on remission of

sentence, was sufficiently foreseeable for the applicant. However, in the

light of the considerations that led it to find a violation of Article 7 of the

Convention, the Court considers that at the material time the applicant could

not have foreseen to a reasonable degree that the effective duration of her

term of imprisonment would be increased by almost nine years, cancelling

out the remission to which she was entitled under the old Criminal Code of

1973 in exchange for work done. In particular, she could not have foreseen,

at the time when all her sentences were combined into one, that the method

used to calculate remissions of sentence would change as a result of a

departure from precedent by the Supreme Court in 2006, and that the new

approach would be applied retroactively.

75. Having regard to all the facts of the case, the Court considers that the

applicants detention after 3 July 2008 has not been lawful. There has

accordingly been a violation of Article 5 1 of the Convention.

III. ALLEGED VIOLATION OF ARTICLE 14 OF THE CONVENTION

76. Lastly, the applicant complained that the new precedent set by the

Supreme Court had been used by the Spanish courts to prevent or delay the

release of prisoners who belonged to ETA. Prisoners convicted for terrorist

24

DEL RIO PRADA v. SPAIN JUDGMENT

offences were specially targeted, while the new calculation method was

rarely used in respect of other detainees. The purpose of the new approach

was primarily political. In practice it created a new, virtually lifetime

sentence for Basque political prisoners. She relied on Article 14 read in

conjunction with Articles 5 1 and 7 of the Convention. Article 14 reads as

follows:

The enjoyment of the rights and freedoms set forth in [the] Convention shall be

secured without discrimination on any ground such as sex, race, colour, language,

religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, association with a

national minority, property, birth or other status.

77. The Government disagreed.

78. The Court considers that the principles applied by the Audiencia

Nacional to calculate the applicants remission were based on the precedent

set by the Supreme Court in its judgment of 28 February 2006. This was a

general precedent and was therefore equally applicable to individuals who

were not members of ETA.

79. Accordingly, the Court must reject this complaint as being

manifestly ill-founded within the meaning of Article 35 3 (a) and 4 of the

Convention.

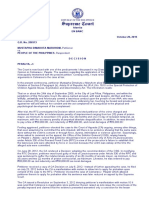

IV. ARTICLES 46 AND 41 OF THE CONVENTION

A. Article 46 of the Convention

80. Under the terms of this provision:

1. The High Contracting Parties undertake to abide by the final judgment of the

Court in any case to which they are parties.

2. The final judgment of the Court shall be transmitted to the Committee of

Ministers, which shall supervise its execution.

81. By virtue of Article 46 of the Convention, the High Contracting

Parties undertake to abide by the final judgment of the Court in any case to

which they are parties, execution being supervised by the Committee of

Ministers. This means that when the Court finds a violation, the respondent

State is under a legal obligation not just to pay those concerned the sums

awarded by way of just satisfaction under Article 41, but also to take the

necessary general and/or, if appropriate, individual measures. The Courts

judgments being essentially declaratory in nature, the respondent State

remains free, subject to monitoring by the Committee of Ministers, to

choose the means by which it will discharge its legal obligation under

Article 46 of the Convention, provided that such means are compatible with

the conclusions set out in the Courts judgment (see Scozzari and Giunta v.

Italy [GC], nos. 39221/98 and 41963/98, 249, ECHR 2000-VIII, and

Scoppola v. Italy (no. 2) [GC], no. 10249/03, 147, 17 September 2009).

DEL RIO PRADA v. SPAIN JUDGMENT

25

82. Nevertheless, exceptionally, with a view to assisting the respondent

State in fulfilling its obligations under Article 46, the Court has sought to

indicate the type of measure that might be taken to put an end to the

situation identified (see, for example, Broniowski v. Poland [GC],

no. 31443/96, 194, ECHR 2004-V). In other exceptional cases, the nature

of the violation found may be such as to leave no real choice as to the

measures required to remedy it and the Court may decide to indicate only

one such measure (see Assanidze v. Georgia [GC], no. 71503/01, 202203, ECHR 2004-II, Alexanian v. Russia, no. 46468/06, 239-240, 22

December 2008, and Fatullayev v. Azerbaijan, no. 40984/07, 176-177,

22 April 2010).

83. The Court considers that the present case belongs to this lastmentioned category. Having regard to the particular circumstances of the

case and to the urgent need to put an end to the violation of Articles 7 and

5 1 of the Convention (see paragraphs 64 and 75 above), the Court

considers it incumbent on the respondent State to ensure that the applicant is

released at the earliest possible date.

B. Article 41 of the Convention

84. Under the terms of Article 41 of the Convention,

If the Court finds that there has been a violation of the Convention or the Protocols

thereto, and if the internal law of the High Contracting Party concerned allows only

partial reparation to be made, the Court shall, if necessary, afford just satisfaction to

the injured party.

1. Damage

85. The applicant claimed 50,000 euros (EUR) in respect of the nonpecuniary damage allegedly sustained.

86. The Government considered that sum disproportionate, and pointed

out that in the event of a finding of a violation of the Convention and if the

applicant was still in detention when the judgment was pronounced, it was

not to be excluded that she might obtain restitutio in integrum at the

domestic level, in conformity with the case-law of the Constitutional Court.

87. Ruling on an equitable basis, as required by Article 41 of the

Convention, the Court awards the applicant EUR 30,000 in respect of nonpecuniary damage.

2. Costs and expenses

88. The applicant claimed EUR 1,500 for the costs and expenses

incurred before the Court.

89. The Government left the matter to the Courts discretion.

26

DEL RIO PRADA v. SPAIN JUDGMENT

90. In the present case, on the basis of the information in its possession

and its case-law, the Court considers the sum of EUR 1,500 for costs and

expenses for the proceedings before the Court to be reasonable and awards

the applicant that amount.

C. Default interest

91. The Court considers it appropriate that the default interest should be

based on the marginal lending rate of the European Central Bank, to which

should be added three percentage points.

FOR THESE REASONS, THE COURT UNANIMOUSLY,

1. Joins to the merits the Governments preliminary objection and

dismisses it;

2. Declares the application admissible in respect of the complaints under

Articles 7 and 5 1 of the Convention and the remainder of the

application inadmissible;

3. Holds that there has been a violation of Article 7 of the Convention;

4. Holds that there has been a violation of Article 5 1 of the Convention;

5. Holds that the respondent State is to ensure that the applicant is released

at the earliest possible date (see paragraph 83 above);

6. Holds