Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Sacred Celtic Sites

Caricato da

Cristobo CarrínDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Sacred Celtic Sites

Caricato da

Cristobo CarrínCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Pan-Celtic?

Sacred Site Types

of the Ancient Celts.

by

Jeff Boice

Harvard University

October 23, 1995

Sacred Site Types, J. Boice

Sacred Site Types

There are many variations on the sacred theme when it comes to Celtic

archaeological sites. At Entremont and Roquepertuse are the remains of what appear to

be temple sites complete with pillars, figures, and heads both real and recreated in the

form of stylized carvings. Such formal construction used to create sacred space is

unusual in Celtic practices and appears to have been heavily influenced by the Romans.

Yet the end result is recognizably Celtic in style.

Much more common are sites that have sometimes been described as shrines

such as those found at London Heathrow Airport and the Marne. These sites typically

consist of an earthen enclosure (sometimes double squares sometimes circular) of

varying dimension within which are grouped the remains of one or several structures as

evidenced by post holes. The structures are sometimes rectangular and sometimes

circular, sometimes there are grave sites nearby, and sometimes there are cremation

remains. Occasionally there are objects left which can be described as votive.

Interpreting these structures as shrines may be questionable, but is somewhat

supported by finds such as the circular shrine at Housesteads on Hadrians Wall.

Though most likely not Celtic, the small circular structure at Housesteads is certainly a

shrine, and the similarities between this site and other more ambiguous sites lends a

degree of support to those who see shrines in many of these enclosures.

A variation on the basic earthen enclosure is the elongated rectangular site type

such as those found at Libenice and Aulnay-aux-Planches. These sites are often quite

massive in dimensions, and while the evidence of structures within the earthen

enclosures is comparatively sparse, grave sites and cremation remains are often found

within the enclosed space. A few of these enclosures have been found to contain shafts

and/or pits which appear to be ritual in nature. In the enclosure at Holzhausen are three

shafts, one of which was one hundred and twenty feet deep.

The appearance of ritual shafts within enclosures makes it possible to relate these

Sacred Site Types, J. Boice

sites to many other sites which contain shafts or pits, but are not accompanied by

enclosures. At most of these non-enclosed sites, the shafts have been found to contain

various objects which can be described as votive along with evidence for sacrificial

practices. Some shafts and pits have previously been described as wells and may

certainly have functioned as such at some point in time.

The votive nature of the ritual shafts along with their alternate identification as wells

leads to what is probably the simplest sacred site type, the votive body of water. A rich

array of material, often contained in cauldrons, has been recovered from various pools,

springs and wells at sites such as La Tne, Llyn Cerrig Bach, the Giants Springs and

Gundestrup where the Gundestrup Cauldron was found. In addition, at the spring of Les

Roches over five thousand wooden figures in the shape of heads, body organs and full

figures were discovered, and at the source of the River Seine some two hundred such

wooden figures were also found. Is this an echo of the head cult exhibited by the two

temple sites with which this discussion began? If all of these site types are Celtic, how

are they related, and what do they tell us about Celtic religious practices?

Pan-Celtic Practice?

The Celts were not a highly centralized people as where the Romans, and with the

evidence from place names and inscriptions pointing to a highly localized assortment of

Celtic deities, perhaps it is expecting too much to attempt to tie the various sacred site

types together into a tightly knit framework representing Celtic religious practices.

Indeed, it only seems logical to expect the practice to vary as the deity being honored

and that deitys function in the culture varies.

Additionally, the classical and vernacular texts point to a much more natural form

of sacred space, or nemeton, implying a sacred clearing in a wood or a sacred grove

rather than the constructed enclosures of the types discussed here. The difficulty lies in

the fact that such sacred groves and clearings do not leave archaeological evidence, yet

Sacred Site Types, J. Boice

their existence should be considered in relation to the more naturally occurring springs,

pools and wells and the formal enclosures that have been uncovered. Perhaps we are

here seeing a variance in practice between the rural Celts and their more urbanized

counterparts?

Another consideration might be differences between sites that were used more or

less as cemeteries and those which were more sacrificial or votive in nature. Perhaps

the temples and ritual shaft enclosures were urbanized or at least regionalized sites

dedicated to honoring the gods of battle complete with severed heads of vanquished

foes and frequent sacrifices while many of the smaller shrines enclosed in earthen

works and accompanied by several structures were of the burial type and oriented

towards smaller communities with the votive springs, pools and well sites being all that

remain of the rural Celtic practices? There are many possibilities.

Conclusion

Depending on ones perspective, deciphering the archaeological evidence can be

either a great opportunity or a great challenge. Certainly there is tremendous room for

interpretation, and imagination could and should play a part in the process. But always,

these interpretations are works in progress, evolving as more evidence is uncovered,

and since we must rely on a certain degree of interpretation when it comes to imposing

patterns on the evidence, it seems prudent to accept, perhaps even to embrace, the

subjectivity inherent in the sense-making process.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Religious Practices of The Pre-Christian and Viking AgeDocumento60 pagineReligious Practices of The Pre-Christian and Viking AgeAitziber Conesa MadinabeitiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Prehistoric Religion: General CharacteristicsDocumento10 paginePrehistoric Religion: General CharacteristicsLord PindarNessuna valutazione finora

- Burying the Dead: An Archaeological History of Burial Grounds, Graveyards & CemeteriesDa EverandBurying the Dead: An Archaeological History of Burial Grounds, Graveyards & CemeteriesNessuna valutazione finora

- The Bas Library - Yes They Are - 2015-11-05Documento8 pagineThe Bas Library - Yes They Are - 2015-11-05willylafleurNessuna valutazione finora

- Why Not Paint An Altar A Study of Where PDFDocumento28 pagineWhy Not Paint An Altar A Study of Where PDFartemida_Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sweet Spices in The TombDocumento32 pagineSweet Spices in The TombDennysJXPNessuna valutazione finora

- Defining The Holy Ch1 Hamilton SpicerDocumento10 pagineDefining The Holy Ch1 Hamilton SpicerArchaeology_RONessuna valutazione finora

- Labyrinths from the Outside In: Walking to Spiritual Insight—A Beginner's GuideDa EverandLabyrinths from the Outside In: Walking to Spiritual Insight—A Beginner's GuideValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (3)

- The Pagan Religions of The Ancient British Isles - Their Nature and LegacyDocumento423 pagineThe Pagan Religions of The Ancient British Isles - Their Nature and LegacyLeona May Miles Fox100% (19)

- Stories in Stone: New York: A Field Guide to New York City Area Cemeteries & Their ResidentsDa EverandStories in Stone: New York: A Field Guide to New York City Area Cemeteries & Their ResidentsNessuna valutazione finora

- Life of St. Declan of Ardmore and Life of St. Mochuda of LismoreDa EverandLife of St. Declan of Ardmore and Life of St. Mochuda of LismoreNessuna valutazione finora

- Understanding The Structures of Early CH PDFDocumento24 pagineUnderstanding The Structures of Early CH PDFGheorghe AndreeaNessuna valutazione finora

- Babylonian-Assyrian Religion, Part Of, Jastrow 1898Documento16 pagineBabylonian-Assyrian Religion, Part Of, Jastrow 1898shayfaranasNessuna valutazione finora

- The Dead Sea ScrollsDocumento21 pagineThe Dead Sea Scrollsm.a.tolbartNessuna valutazione finora

- Ossuary: Jump To Navigation Jump To SearchDocumento4 pagineOssuary: Jump To Navigation Jump To SearchSorinNessuna valutazione finora

- Despre Vasele Ritualice Din Sanctuarele Neolitice Sud-Est EuropeneDocumento22 pagineDespre Vasele Ritualice Din Sanctuarele Neolitice Sud-Est EuropeneRazvan DanailaNessuna valutazione finora

- Celtic Mythology (Illustrated Edition): Folklore & Legends of the Iron Age CeltsDa EverandCeltic Mythology (Illustrated Edition): Folklore & Legends of the Iron Age CeltsNessuna valutazione finora

- Abbeys Monasteries and Priories Explained: Britain's Living HistoryDa EverandAbbeys Monasteries and Priories Explained: Britain's Living HistoryNessuna valutazione finora

- Lay LinesDocumento15 pagineLay LinesPeter Manson0% (1)

- Body Part ReliquariesDocumento6 pagineBody Part ReliquariesJeremy HoffeldNessuna valutazione finora

- Verbeia: Goddess of WharfedaleDocumento29 pagineVerbeia: Goddess of Wharfedalegyruscope100% (1)

- Understanding The Structures of Early CHDocumento24 pagineUnderstanding The Structures of Early CHMarcus TulliusNessuna valutazione finora

- Burying The Dead': Making Muslim Space in Britain : Humayun AnsariDocumento22 pagineBurying The Dead': Making Muslim Space in Britain : Humayun AnsariJoseph HernandezNessuna valutazione finora

- Church Curiosities: Strange Objects and Bizarre LegendsDa EverandChurch Curiosities: Strange Objects and Bizarre LegendsNessuna valutazione finora

- Gregory Schopen - RelicDocumento9 pagineGregory Schopen - RelicƁuddhisterie20% (1)

- The Old Testament in the Light of the Historical Records and Legends of Assyria and BabyloniaDa EverandThe Old Testament in the Light of the Historical Records and Legends of Assyria and BabyloniaValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- The Locus of The Sacred in The Celtic OtherworldDocumento9 pagineThe Locus of The Sacred in The Celtic OtherworldSouss OuNessuna valutazione finora

- Tomov T - Four - Scandinavian - Ship - Graffiti - From - Hag PDFDocumento17 pagineTomov T - Four - Scandinavian - Ship - Graffiti - From - Hag PDFgoshoNessuna valutazione finora

- The Art of The Yellow Springs (2011)Documento274 pagineThe Art of The Yellow Springs (2011)Hanjun HuangNessuna valutazione finora

- Stonehenge, a Temple Restor'd to the British DruidsDa EverandStonehenge, a Temple Restor'd to the British DruidsNessuna valutazione finora

- Jean Danielou - Primitive Christian Symbols PDFDocumento180 pagineJean Danielou - Primitive Christian Symbols PDFsdist100% (4)

- The Ancient Celtic Religion of Gaul DuriDocumento20 pagineThe Ancient Celtic Religion of Gaul DuriFederico MisirocchiNessuna valutazione finora

- Grave Disturbances: The Archaeology of Post-depositional Interactions with the DeadDa EverandGrave Disturbances: The Archaeology of Post-depositional Interactions with the DeadEdeltraud AspöckNessuna valutazione finora

- Sculptured Stones of Scotland - John Stuart - 1856Documento378 pagineSculptured Stones of Scotland - John Stuart - 1856Sergio MotaNessuna valutazione finora

- Gregory Schopen - Stūpa and Tīrtha: Tibetan Mortuary Practices and An Unrecognized Form of Burial Ad Sanctos at Buddhist Sites in IndiaDocumento21 pagineGregory Schopen - Stūpa and Tīrtha: Tibetan Mortuary Practices and An Unrecognized Form of Burial Ad Sanctos at Buddhist Sites in IndiaƁuddhisterie2Nessuna valutazione finora

- Aesthetics and the Incarnation in Early Medieval Britain: Materiality and the Flesh of the WordDa EverandAesthetics and the Incarnation in Early Medieval Britain: Materiality and the Flesh of the WordNessuna valutazione finora

- Furta Sacra: Thefts of Relics in the Central Middle Ages - Revised EditionDa EverandFurta Sacra: Thefts of Relics in the Central Middle Ages - Revised EditionValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (2)

- Full Download Book Electromagnetic Composites Handbook Models Measurement and Characterization PDFDocumento22 pagineFull Download Book Electromagnetic Composites Handbook Models Measurement and Characterization PDFduane.lundgren266100% (12)

- 256 Rosslyn Article Ley Lines and Rosslyn ChapelDocumento4 pagine256 Rosslyn Article Ley Lines and Rosslyn ChapelKristine Mae AbanadorNessuna valutazione finora

- The Art of Memory: Historic Cemeteries of Grand Rapids, MichiganDa EverandThe Art of Memory: Historic Cemeteries of Grand Rapids, MichiganValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- The Dead Sea Scrolls: The Discovery Heard around the WorldDa EverandThe Dead Sea Scrolls: The Discovery Heard around the WorldNessuna valutazione finora

- Reliquary: Jump To Navigation Jump To SearchDocumento7 pagineReliquary: Jump To Navigation Jump To SearchKiranDevNessuna valutazione finora

- The Shaft GravesDocumento12 pagineThe Shaft GravesSavvasAntartopoulosNessuna valutazione finora

- From Here To Eternity - Traveling The World To Find The Good DeathDocumento175 pagineFrom Here To Eternity - Traveling The World To Find The Good DeathsofiaNessuna valutazione finora

- The History of A 4th C. B.C. Tumulus atDocumento48 pagineThe History of A 4th C. B.C. Tumulus atPAssentNessuna valutazione finora

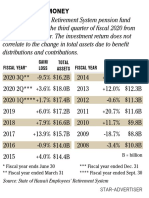

- Tracking The MoneyDocumento1 paginaTracking The MoneyHonolulu Star-AdvertiserNessuna valutazione finora

- Crematorium Public Hearing SlidesDocumento21 pagineCrematorium Public Hearing Slidesnahnah2001100% (1)

- Technical Specification Gas FurnaceDocumento5 pagineTechnical Specification Gas FurnaceBasavaraj M PatilNessuna valutazione finora

- C. J. Arnold - An Archaeology of The Early Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms (1997, Routledge) PDFDocumento278 pagineC. J. Arnold - An Archaeology of The Early Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms (1997, Routledge) PDFBaud Wolf100% (3)

- Bruck, J - Fragmentation, Person Hood and The Social Construction of Technology in Middle and Late Bronze Age BritainDocumento21 pagineBruck, J - Fragmentation, Person Hood and The Social Construction of Technology in Middle and Late Bronze Age BritainEtel ColicNessuna valutazione finora

- SITE Archaeologia Bulgarica 3 2018Documento12 pagineSITE Archaeologia Bulgarica 3 2018Dan Tudor MarinescuNessuna valutazione finora

- Taking Children To FuneralsDocumento6 pagineTaking Children To FuneralsViorica CălimanNessuna valutazione finora

- Archaic Funerary Rites in Ancient Macedonia: Contribution of Old Excavations To Present-Day Researches - Nathalie Del SocorroDocumento8 pagineArchaic Funerary Rites in Ancient Macedonia: Contribution of Old Excavations To Present-Day Researches - Nathalie Del SocorroSonjce Marceva100% (1)

- GrimalkinDocumento32 pagineGrimalkinNicolas TorresNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit Four Review Guide: Art in The Ancient Mediterranean. AP Art History, Spring 2017Documento3 pagineUnit Four Review Guide: Art in The Ancient Mediterranean. AP Art History, Spring 2017young kimNessuna valutazione finora

- Paco ParkDocumento5 paginePaco ParkRosheNessuna valutazione finora

- Percy Bysshe Shelley - WikipediaDocumento15 paginePercy Bysshe Shelley - WikipediaSajadNessuna valutazione finora

- Funeral Rites and Customs in The Roman EmpireDocumento33 pagineFuneral Rites and Customs in The Roman EmpireIoanaCristina SpiridonNessuna valutazione finora

- A Roof Over The Dead:: Communal Tombs and Family StructureDocumento23 pagineA Roof Over The Dead:: Communal Tombs and Family Structureapi-19814021100% (1)

- TV Scriptwriting in FilipinoDocumento20 pagineTV Scriptwriting in FilipinoMahalia SultanNessuna valutazione finora

- Terracotta WarriorsDocumento15 pagineTerracotta WarriorsSamuel WongNessuna valutazione finora

- Amen, Carol - The Last Testament - MS, Aug 81Documento11 pagineAmen, Carol - The Last Testament - MS, Aug 81Bruce Armstrong100% (11)

- The Night of Counting YearsDocumento61 pagineThe Night of Counting YearsspeppNessuna valutazione finora

- Encyclopedia of AntiquitiesDocumento512 pagineEncyclopedia of AntiquitiesSolo Doe100% (2)

- Examination of The Lemures and The Lemuria. by Jarrod LuxDocumento82 pagineExamination of The Lemures and The Lemuria. by Jarrod LuxadambelialNessuna valutazione finora

- Nature of The Case:: Melfi V Mount Sinai HospDocumento2 pagineNature of The Case:: Melfi V Mount Sinai HospLiamNessuna valutazione finora

- Funeral Practices and Burial CustomsDocumento2 pagineFuneral Practices and Burial CustomsMarisel SanchezNessuna valutazione finora

- Vilas County News-Review, Dec. 28, 2011 - SECTION ADocumento14 pagineVilas County News-Review, Dec. 28, 2011 - SECTION ANews-ReviewNessuna valutazione finora

- Biography of Rizal - Rafael PalmaDocumento22 pagineBiography of Rizal - Rafael PalmaEmmanuel Plaza60% (10)

- The ChapelDocumento7 pagineThe ChapeldannyreadsNessuna valutazione finora

- New Caltrain Station Construction Arrives: Oil Makes JumpDocumento32 pagineNew Caltrain Station Construction Arrives: Oil Makes JumpSan Mateo Daily JournalNessuna valutazione finora

- PoemDocumento18 paginePoemhemanta saikiaNessuna valutazione finora