Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

The Gender Gap in Economists' Beliefs

Caricato da

Shane FerroTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

The Gender Gap in Economists' Beliefs

Caricato da

Shane FerroCopyright:

Formati disponibili

ARE DISAGREEMENTS AMONG MALE AND FEMALE ECONOMISTS

MARGINAL AT BEST?: A SURVEY OF AEA MEMBERS AND THEIR VIEWS

ON ECONOMICS AND ECONOMIC POLICY

ANN MARI MAY, MARY G. MCGARVEY, and ROBERT WHAPLES

The authors survey economists in the United States holding membership in the

American Economic Association (AEA) to determine if there are signicant differences

in views between male and female economists on important policy issues. Controlling

for place of current employment (academic institution with graduate program,

academic institutionundergraduate only, government, for-prot institution) and

decade of PhD, the authors nd many areas in which economists agree. However,

important differences exist in the views of male and female economists on issues

including the minimum wage, views on labor standards, health insurance, and

especially on explanations for the gender wage gap and issues of equal opportunity

in the labor market and the economics profession itself. These results lend support to

the notion that gender diversity in policy-making circles may be an important aspect

in broadening the menu of public policy choices. (JEL A11, J78, A14)

I. INTRODUCTION

Few changes in the demographics of higher

education in the United States have been as

pronounced as the increasing percentage of doc-

toral degrees awarded to women in the past

40 years. In 1975, men received the majority

of bachelors, masters, and doctoral degrees; by

2000, the majority of bachelors and masters

degrees were awarded to women. In 2002, for

the rst time in U.S. history, more American

women than American men received doctoral

degrees from U.S. universities and today more

The authors would like to thank Professor Julia McQuil-

lan, Director of the Bureau for Sociological Research, Uni-

versity of Nebraska-Lincoln for her helpful suggestions

on the survey questionnaire, Michael L. May, Swarthmore

College 11 for his research assistance, and the Research

Fund of the Department of Economics at the University of

Nebraska-Lincoln for assistance in funding a portion of this

research. We also thank three anonymous referees for their

very helpful comments and suggestions.

May: Professor of Economics, Department of Economics,

University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, NE 68588-

0489. Phone 402-472-3369, E-mail amay1@unl.edu

McGarvey: Associate Professor, Department of Economics,

University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, NE 68588-

0489. Phone 402-472-9415, E-mail mmcgarvey@

unl.edu

Whaples: Professor of Economics, Department of Eco-

nomics, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, NC

27109-7505. Phone 336-758-4916, E-mail whaples@

wfu.edu

doctorates are awarded to women than to men

at U.S. universities.

1

Although the proportion of women in eco-

nomics continues to lag behind that of other

social science disciplines, data from the Survey

of Earned Doctorates show that women rep-

resent 34.4% of new doctorates in economics

from U.S. universities in 2011, up from 28.1%

in 2001 (Doctorate Recipients from U.S. Uni-

versities 2011: Table 14 National Science Foun-

dation 2012). This represents a 6.3 percentage

point increase over the period as compared

with an average 2.5 percentage point increase

for all elds. As a result, increasing num-

bers of female economists are actively involved

1. Earned Degrees Conferred: 18702000, Postsec-

ondary Education Opportunity, Number 116, February 2002

available at http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICWebPortal/custom/

portlets/recordDetails/detailmini.jsp?_nfpb=true&_&ERIC

ExtSearch_SearchValue_0=ED473779&ERICExtSearch_

SearchType_0=no&accno=ED473779. Accessed December

6, 2009.

ABBREVIATIONS

AEA: American Economic Association

GDP: Gross Domestic Product

GLS: Generalized Least Squares

OLS: Ordinary Least Squares

SUR: Seeming Unrelated Regression

111

Contemporary Economic Policy (ISSN 1465-7287)

Vol. 32, No. 1, January 2014, 111132

Online Early publication February 25, 2013

doi:10.1111/coep.12004

2013 Western Economic Association International

112 CONTEMPORARY ECONOMIC POLICY

in research and policy making on a variety

of levels including the Board of Governors

of the Federal Reserve Bank to the Coun-

cil of Economic Advisors. But does it make

any difference if men or women are at the

table when economic policies are debated and

alternatives considered? Or, are disagreements

between male and female economists marginal

at best?

In this study, we survey male and female

economists who are members of the Ameri-

can Economic Association (AEA) and provide

what is the rst systematic study of the views

of male and female economists on a wide vari-

ety of policy issues to determine if there are

differences in the views of male and female

economists after controlling for place of current

employment (academic institution with graduate

program, academic institutionundergraduate

only, government, for-prot institution) and

decade of PhD.

A. Consensus and the Economics Profession

Numerous studies using survey data to exam-

ine the degree of consensus among economists

have been published over the past 25 years

(Alston, Kearl, and Vaughan 1992; Frey et al.

1984; Fuller and Geide-Stevenson 2003; Kearl

et al. 1979; Whaples 2006). While these sur-

veys appeared relatively late in economics

as compared with other social science disci-

plines, the importance of consensus within the

discipline has a long history. In fact, con-

cern over consensus dates back to the ori-

gins of the AEA where the annual meeting

offered a forum for developing consensus in

a discipline thought to reect a sometimes

embarrassingly wide array of views on eco-

nomic policy questions. Economists, in particu-

lar, had much to gain in the professionalization

of higher education and the lack of consensus

on economic questions served as yet one more

reminder of the possibly less-than-scientic

nature of a discipline aspiring to be scientic

(Coats 1993).

Recent studies examine consensus among

economists by focusing on underlying assump-

tions, methodology, and policy issues. The

results of these studies indicate that economists

are less supportive of government interven-

tion in the economy than their counterparts in

other social science disciplines (Klein and Stern

2005, 2007) and that a fair degree of con-

sensus exists among economists. Kearl et al.

(1979, 36) in their study of U.S. economists in

a survey conducted in 1976 report more con-

sensus on microeconomic than macroeconomic

issues, but overall report that the perceptions of

widespread disagreement are simply wrong. In

a follow-up study, Alston, Kearl, and Vaughan

(1992) nd that although opinions of U.S.

economists on particular issues had shifted, a

similar pattern of consensus emerged with the

caveat that degree vintage and subgroup (AEA

membership, government economists, business

economists, teachers of principles of economics

courses at 4-year institutions, and institutional

economists) are also important determinants of

consensus on various questions. Alston, Kearl,

and Vaughan (1992) nd considerable consen-

sus among economists overall. Yet, as Fuchs

et al. (1998) later point out, the seven ques-

tions about policy in Alston, Kearl, and Vaughan

(1992) show a very high level of disagreement.

In their own study Fuchs et al. (1998) nd con-

siderable disagreement between labor and public

economists about policy proposals in their areas

of specialization. In an additional study, Fuchs

(1996) surveyed health economists and found

considerable disagreement about major issues of

health policy.

Other studies have examined the inuence

of international differences (Frey et al. 1984),

age differences or age upon receipt of degree

(Alston, Kearl, and Vaughan 1992; Klein and

Stern 2005), political party and voting pat-

terns (Klein and Stern 2005, 2007), school

of thought (Alston and Vaughan 1993), and

economic eld (Fuller and Geide-Stevenson

2003; Kearl et al. 1979) to determine if these

factors produce differences in the views of

economists. Yet, absent from these discussions

is any examination of gender differences among

economists.

In contrast to these previous studies, only few

studies examine gender differences in opinions

of economists.

2

Davis (1997), in his study of

AEA members, examines economists views of

methodology, the social value of research, per-

ceptions about the publication of that research,

and perceptions about the inuence of race and

gender on economic research. He reports that

there are signicant differences in the views

of male and female economists with respect

to whether author recognition among profes-

sional economists inuences the probability of

2. Some studies on gender differences in economic

policy on single issues offer similarly interesting results.

See, for example, Burgoon and Niscox (2012).

MAY, MCGARVEY & WHAPLES: AEA MEMBERS VIEWS 113

an articles acceptance in refereed economics

journals in the United States, whether there is a

good-old-boy network in the economics pro-

fession, and whether economists are amenable

to interdisciplinary research approaches. Specif-

ically, Davis nds that although the majority of

male and female economists have similar opin-

ions, women typically reach a much stronger

consensusparticularly on issues of equity and

fairness in the economics profession.

In her study of AEA economists conducted

in 1992, Albelda (1997) examines a variety of

questions concerning gender and the economics

profession. According to her, men were much

less interested than women in having more atten-

tion paid to topics such as womens labor force

participation, the impact of scal and mone-

tary policies on women and the family structure,

wage discrimination, and the economic status of

minority women (Albelda 1997, 7980). More-

over, there was little support for the notion

that feminism has impacted the discipline of

economicsnor did economists express much

interest in seeing more feminist economic anal-

ysis. Most notable, however, were the large

gender gaps in response to questions about the

treatment of women in the economics profession

(Albelda 1997, 69). As she reports, almost one-

third of male respondents agree with the state-

ment that it is easier for women to get tenure

and promotions than it is for men, while less

than 4% of women agreed with the statement

(Albelda 1997, 81).

Hedengren, Klein, and Milton (2010) exam-

ine gender differences in policy-oriented peti-

tions endorsed by economists, nding that

men are much more likely to sign liberty-

enhancing petitions, which call for a smaller

role for the state, while women economists are

somewhat more likely to endorse petitions call-

ing for greater governmental intervention. Davis

et al. (2011) conduct a survey on a wide range

of issues (including favorite economic thinkers,

economics journals, and blogs) and nd that

women economists are much more likely than

men to be members of the Democratic Party and

to favor policies that restrict individual liberty.

In addition, Stastny (2010) nds that women

economists in the Czech Republic tend to favor

much more government intervention than do

male economists.

Although these studies offer important

insights into gender differences on views of the

economics profession, they ask a fairly narrow

range of questions and are not designed to sys-

tematically explore the nuances of differences

between male and female economists. Given

the changing demographics of the economics

profession over the past 30 years, these differ-

ences, if they exist, may have signicant impli-

cations for policy-making outcomes.

B. Gender and Economics in the United States

Although the gender gap in voting and

party identication has been a topic of wide-

spread interest since the 1980 election, less

attention has been paid to gender differences in

policy preferences. Yet, several studies indicate

that gender differences in policy preferences

exist in the United States and have increased

since the 1970s (Ingelhart and Norris 2000; Pew

Research Center 2009; Saad 2003; Shapiro and

Mahajan 1986; Smith 1984). While disagree-

ment exists as to the cause of these differences

in voting patterns, party identication, and pub-

lic opinion surveys on policy issues, women and

men appear to differ most on matters concern-

ing violence and force and so-called compassion

issues concerning aid to the poor, unemployed,

sick, and others in need, and in their views on

regulatory policies (Shapiro and Mahajan 1986,

4445).

Although gender differences in the general

population are well studied, gender differences

in the views of economists have received little

attention. In fact, no systematic study of gender

differences in views of American economists on

a wide variety of economic policy issues has yet

been undertaken. Our study attempts to remedy

this by examining the views of male and female

economists who are members of the AEA in

the United States. Using survey data on core

precepts and approaches in economics, views

on market solutions and government interven-

tion, specic policy issues, and gender equality

in economics and society we ask the question,

Do male and female economists share the same

views on underlying assumptions, methodologi-

cal approaches, policy solutions, perceived prob-

lems in economics, and equal opportunity in

society and the economics profession? Because

survey data from noneconomists indicate that

there are often signicant gender differences

in views on policy issues (Saad 2003), we

are interested to see if these differences disap-

pear among economists with shared training and

backgrounds.

114 CONTEMPORARY ECONOMIC POLICY

II. METHODOLOGY

A. Data and Descriptive Statistics

Our goal is to estimate the extent of dif-

ferences in opinions on economic methodology

and policy issues between male and female

economists with doctoral degrees who are mem-

bers of the AEA. The population from which

we sampled is the list of members in the 2007

AEA Directory who received both their under-

graduate and PhD degrees from U.S. insti-

tutions.

3

The selection process yielded 202

randomly selected male members and 202 ran-

domly selected female members to whom the

survey was mailed in early November 2008. The

overall response rate was 35.4% which is similar

to previous surveys.

4

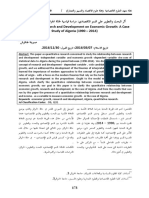

Table 1 contains descriptive statistics (overall

and disaggregated by sex) for the entire sam-

ple, for the 143 members who returned usable

surveys, and for the 261 nonresponders. Char-

acteristics of the AEA members include demo-

graphic information on sex, year of PhD, and

current type of employment. This information

was obtained from survey responses of those

who returned the surveys and from the AEA

directory entries of the nonresponders. Addition-

ally, Table 1 reports whether or not the AEA

member chose to list his/her research interests

in the 2007 AEA directory. This information

was included as an indication not only of the

economists research activity, but also the will-

ingness of the individual to respond to survey

questions.

The original, random sample of AEA mem-

bers was evenly divided between men and

women by design. Approximately 67% of those

sampled are employed in academic institutions

with 41% teaching in graduate programs and

26% in undergraduate programs. Fourteen per-

cent of those sampled work in the for-prot

3. The 2007 AEA membership directory has 1,116 pages

of members. To create a sample of approximately 200 male

and 200 female members we randomly picked a starting

page between 1 and 5 and then selected the rst male and the

rst female to meet the selection criteria. (Many members

do not list information regarding their degrees and had to be

skipped.) The search procedure was repeated by fth/sixth

page thereafter. This yielded 202 males and 202 females (in

one instance there was a stretch of six pages over which no

female met the criteria). Sex was usually obvious from the

individuals rst name, but an Internet search of individuals

was conducted in cases of ambiguity.

4. Response rates among AEA member in recent sur-

veys include 34.4% in Alston, Kearl, and Vaughan (1992),

30.8% in Fuller and Geide-Stevenson (2003), 36.3% in

Whaples and Heckelman (2005), 26.6% in Klein and Stern

(2005), and 40.0% in Whaples (2006).

sector and 11% are employed by the govern-

ment. The remaining 8% are either retired, not in

the formal labor market, or working in the non-

prot sector. Although, in our sample, it is more

likely for women to be employed in academic

institutions than men, and more likely for men

to work in the government or for-prot sectors

than women, these differences in employment

rates are not statistically signicantly different

from 0. The economists in the AEA survey

earned their doctoral degrees about 22 years

ago with womens degrees earned about 5 years

more recently than mens and the average differ-

ence is statistically signicant. It is interesting

that, in our random sample of AEA members,

male economists are more likely to list their

research interests in the AEA directory than

female economists. The 10 percentage point dif-

ference is also statistically signicant.

A comparison of the responders and nonre-

sponders descriptive statistics shows that most

of the characteristics are similar. Forty-ve per-

cent of those responding to the survey are

women, whereas 52% of the nonresponders are

women. The distribution of overall employment

across sectors is roughly the same with the

exception of employment in an academic institu-

tion with a graduate program. Formal statistical

tests nd evidence that the overall proportions

of economists teaching in graduate institutions

differ for the responders and nonresponders

(.35 vs. .44) and that it is the male respon-

ders who are statistically signicantly less likely

(by 11 percentage points) to teach in graduate

institutions than the male nonresponders. The

proportion of economists who list their research

interests in the AEA directory is 55% for the

responders and 62% for the nonresponders. On

average, those responding to the survey received

their PhDs about two and a half years more

recently than those not responding and this dif-

ference is statistically signicant. A smaller pro-

portion of those economists who responded to

the survey received their degrees in the 1970s

than those who did not respond.

Most of the statistically signicant male and

female differences in the original random sam-

ple remain signicant in the sample of respon-

ders. Male economists are more likely to list

their current research in the AEA directory

and received their PhDs earlier than female

economists. In the responders sample, male

economists are more than twice as likely to be

working in the governmental sector as female

economists. Although this relative difference in

MAY, MCGARVEY & WHAPLES: AEA MEMBERS VIEWS 115

T

A

B

L

E

1

C

h

a

r

a

c

t

e

r

i

s

t

i

c

s

o

f

A

E

A

S

u

r

v

e

y

S

a

m

p

l

e

A

E

A

S

u

r

v

e

y

S

a

m

p

l

e

R

e

s

p

o

n

d

e

r

s

t

o

S

u

r

v

e

y

N

o

n

r

e

s

p

o

n

d

e

r

s

T

o

t

a

l

F

e

m

a

l

e

M

a

l

e

T

o

t

a

l

F

e

m

a

l

e

M

a

l

e

T

o

t

a

l

F

e

m

a

l

e

M

a

l

e

V

a

r

i

a

b

l

e

N

M

N

M

N

M

N

M

N

M

N

M

N

M

N

M

N

M

F

e

m

a

l

e

4

0

4

0

.

5

0

1

4

3

0

.

4

5

2

6

1

0

.

5

2

0

.

5

0

0

.

5

0

0

.

5

0

G

r

a

d

u

a

t

e

4

0

3

0

.

4

1

2

0

1

0

.

4

2

2

0

2

0

.

4

1

1

4

2

0

.

3

5

+

6

4

0

.

3

8

7

8

0

.

3

4

+

2

6

1

0

.

4

4

1

3

7

0

.

4

4

1

2

4

0

.

4

5

0

.

4

9

0

.

0

0

0

.

0

0

0

.

4

8

0

.

4

9

0

.

4

8

0

.

5

0

0

.

5

0

0

.

5

0

U

n

d

e

r

g

r

a

d

u

a

t

e

4

0

4

0

.

2

6

2

0

2

0

.

2

9

2

0

2

0

.

2

4

1

4

3

0

.

3

0

6

5

0

.

3

4

7

8

0

.

2

7

2

6

1

0

.

2

4

1

3

7

0

.

2

6

1

2

4

0

.

2

2

0

.

4

4

0

.

0

0

0

.

0

0

0

.

4

6

0

.

4

8

0

.

4

5

0

.

4

3

0

.

4

4

0

.

4

1

F

o

r

P

r

o

t

4

0

3

0

.

1

4

2

0

1

0

.

1

3

2

0

2

0

.

1

5

1

4

3

0

.

1

3

6

5

0

.

1

2

7

8

0

.

1

3

2

6

0

0

.

1

5

1

3

6

0

.

1

3

1

2

4

0

.

1

6

0

.

3

5

0

.

0

0

0

.

0

0

0

.

3

3

0

.

3

3

0

.

3

4

0

.

3

5

0

.

3

4

0

.

3

7

G

o

v

e

r

n

m

e

n

t

4

0

3

0

.

1

1

2

0

1

0

.

0

9

2

0

2

0

.

1

4

1

4

3

0

.

1

3

6

5

0

.

0

7

7

8

0

.

1

7

2

6

0

0

.

1

1

1

3

6

0

.

1

0

1

2

4

0

.

1

2

0

.

3

2

0

.

0

0

0

.

0

0

0

.

3

3

0

.

2

7

0

.

3

8

0

.

3

1

0

.

3

0

0

.

3

3

L

i

s

t

e

d

R

e

s

e

a

r

c

h

4

0

3

0

.

6

0

2

0

1

0

.

5

4

2

0

2

0

.

6

4

1

4

3

0

.

5

5

6

5

0

.

4

7

7

8

0

.

6

0

2

6

0

0

.

6

2

1

3

6

0

.

5

8

1

2

4

0

.

6

7

0

.

4

9

0

.

0

0

0

.

0

0

0

.

5

0

0

.

5

0

0

.

4

9

0

.

4

9

0

.

5

0

0

.

4

7

P

h

D

p

r

e

1

9

7

0

3

9

5

0

.

0

9

1

9

8

0

.

0

6

1

9

7

0

.

1

2

1

4

1

0

.

0

8

6

5

0

.

0

6

7

6

0

.

0

9

2

5

4

0

.

0

9

1

3

3

0

.

0

5

1

2

1

0

.

1

3

0

.

2

8

0

.

2

3

0

.

3

2

0

.

2

7

0

.

2

4

0

.

2

9

0

.

2

9

0

.

2

2

0

.

3

4

P

h

D

1

9

7

0

s

3

9

5

0

.

2

1

1

9

8

0

.

1

6

1

9

7

0

.

2

5

1

4

1

0

.

1

6

+

6

5

0

.

1

2

7

6

0

.

2

0

2

5

4

0

.

2

3

1

3

3

0

.

1

8

1

2

1

0

.

2

9

0

.

4

1

0

.

3

7

0

.

4

4

0

.

3

7

0

.

3

3

0

.

4

0

0

.

4

2

0

.

3

9

0

.

4

6

P

h

D

1

9

8

0

s

3

9

5

0

.

2

9

1

9

8

0

.

2

7

1

9

7

0

.

3

1

1

4

1

0

.

2

8

6

5

0

.

2

6

7

6

0

.

2

9

2

5

4

0

.

3

0

1

3

3

0

.

2

8

1

2

1

0

.

3

2

0

.

4

5

0

.

4

5

0

.

4

6

0

.

4

5

0

.

4

4

0

.

4

6

0

.

4

6

0

.

4

5

0

.

4

7

P

h

D

1

9

9

0

s

3

9

5

0

.

2

3

1

9

8

0

.

2

9

1

9

7

0

.

1

7

1

4

1

0

.

2

6

6

5

0

.

3

2

7

6

0

.

2

1

2

5

4

0

.

2

2

1

3

3

0

.

2

8

1

2

1

0

.

1

5

0

.

4

2

0

.

4

6

0

.

3

8

0

.

4

4

0

.

4

7

0

.

4

1

0

.

4

1

0

.

4

5

0

.

3

6

P

h

D

2

0

0

0

s

3

9

5

0

.

1

8

1

9

8

0

.

2

2

1

9

7

0

.

1

5

1

4

1

0

.

2

2

6

5

0

.

2

3

7

6

0

.

2

1

2

5

4

0

.

1

6

1

3

3

0

.

2

1

1

2

1

0

.

1

1

0

.

3

9

0

.

4

1

0

.

3

6

0

.

4

2

0

.

4

2

0

.

4

1

0

.

3

7

0

.

4

1

0

.

3

1

Y

e

a

r

s

P

h

D

3

9

5

2

1

.

6

3

1

9

8

1

9

.

0

2

1

9

7

2

4

.

2

5

1

4

1

1

9

.

9

8

6

5

1

8

.

1

5

7

6

2

1

.

5

6

2

5

4

2

2

.

5

4

1

3

3

1

9

.

4

5

1

2

1

2

5

.

9

4

1

2

.

6

5

1

2

.

0

6

1

2

.

7

3

1

2

.

7

1

1

1

.

7

9

1

3

.

3

3

1

2

.

5

5

1

2

.

2

0

1

2

.

0

9

N

o

t

e

s

:

S

t

a

n

d

a

r

d

d

e

v

i

a

t

i

o

n

s

a

r

e

b

e

n

e

a

t

h

s

a

m

p

l

e

m

e

a

n

s

.

T

h

e

s

y

m

b

o

l

s

d

e

n

o

t

e

r

e

j

e

c

t

i

o

n

a

t

t

h

e

1

0

%

,

5

%

,

1

%

s

i

g

n

i

c

a

n

c

e

l

e

v

e

l

s

o

f

f

e

m

a

l

e

-

m

a

l

e

e

q

u

a

l

m

e

a

n

s

t

e

s

t

s

w

i

t

h

i

n

A

E

A

m

e

m

b

e

r

s

p

o

p

u

l

a

t

i

o

n

(

u

s

i

n

g

A

E

A

s

u

r

v

e

y

s

a

m

p

l

e

)

,

w

i

t

h

i

n

A

E

A

r

e

s

p

o

n

d

e

r

s

p

o

p

u

l

a

t

i

o

n

(

u

s

i

n

g

A

E

A

s

u

r

v

e

y

s

a

m

p

l

e

)

,

w

i

t

h

i

n

A

E

A

r

e

s

p

o

n

d

e

r

s

p

o

p

u

l

a

t

i

o

n

(

u

s

i

n

g

r

e

s

p

o

n

d

e

r

s

s

a

m

p

l

e

)

,

a

n

d

w

i

t

h

i

n

t

h

e

n

o

n

r

e

s

p

o

n

d

e

r

s

p

o

p

u

l

a

t

i

o

n

(

u

s

i

n

g

n

o

n

r

e

s

p

o

n

d

e

r

s

s

a

m

p

l

e

)

.

T

h

e

s

y

m

b

o

l

s

+

,

+

+

,

+

+

+

d

e

n

o

t

e

r

e

j

e

c

t

i

o

n

a

t

t

h

e

1

0

%

,

5

%

,

1

%

s

i

g

n

i

c

a

n

c

e

l

e

v

e

l

s

f

o

r

t

e

s

t

s

o

f

e

q

u

a

l

m

e

a

n

s

b

e

t

w

e

e

n

r

e

s

p

o

n

d

e

r

s

a

n

d

n

o

n

r

e

s

p

o

n

d

e

r

s

p

o

p

u

l

a

t

i

o

n

s

,

b

o

t

h

o

v

e

r

a

l

l

a

n

d

f

o

r

e

a

c

h

s

e

x

(

u

s

i

n

g

r

e

s

p

o

n

d

e

r

s

a

n

d

n

o

n

r

e

s

p

o

n

d

e

r

s

s

a

m

p

l

e

s

)

.

116 CONTEMPORARY ECONOMIC POLICY

government employment exists in the original

random sample, it is larger and statistically sig-

nicant among the responders.

Our statistical analysis of gender differences

in economists opinions on methodology and

policy issues is based on the responses of those

who returned their surveys; we do not know

the opinions of the nonresponders. It is possi-

ble that estimation using only the observable

survey responses will lead to inconsistent esti-

mates of the gender effect. We address this

issue in the next section by estimating the

decision to respond to the survey as a probit

model and testing for nonresponse bias in our

estimation of gender differences in the group-

level scaled answers using Heckmans (1979)

procedure.

B. Scaled Responses to Group Questions and

Test for Selection Bias

The survey questions can be classied into

ve groups, each group designed to ascertain

the respondents views about different types of

issues. The rst group of questions relate to core

principles in economics and economic method-

ology. The second through fourth groups exam-

ine views on market solutions and government

intervention, government spending, taxing, and

redistribution, and the environment. The fth

group of questions asks specically about equal

opportunity in society and gender equality in

the economics profession. The wide variety of

policy-related questions allows us to examine

possible gender differences on a host of the

most important and topical issues currently fac-

ing economists.

Before examining gender differences in ans-

wers to specic questions, we rst construct an

overall measure of the economists opinion on

each of the ve group topics. The Appendix

describes the construction of each scaled opin-

ion measure and the survey questions upon

which each is based. Tables A1 and A2 provide

descriptive statistics of the opinion measures and

correlations of the responses between topics. We

nd that the Cronbachs values are greater

than .70 for each of the scaled answers, indicat-

ing that each is a reliable measure of the overall

opinion on the group topic.

Our goal is to estimate the mean difference

in opinion on economic methodology and pol-

icy issues of male and female PhD economists

who received their educational training in the

United States. To better isolate the effect of

gender on economists opinions, we need to

control for those variables that are both cor-

related with the economists opinions on pol-

icy and methodology and with the economists

gender. Because female economists received

their terminal degrees more recently, on aver-

age, than male economists, and opinions might

be related to degree vintage, we include four

binary indicators of the decade the PhD was

received as one of our control variables. The

omitted category of economists contains those

who received their PhDs prior to 1970. We

also include controls for the economists place

of employment. Although there were no sta-

tistically signicant differences in the propor-

tions of men and women employed in graduate

or undergraduate-only academic institutions, nor

in the for-prot sectors, there might be differ-

ences in types of employment by gender after

accounting for degree vintage. The economists

opinions on policy issues and methodology

might reasonably be related to, or inuenced

by, their type of work. For these reasons, we

also include the mutually exclusive employment

category variables, graduate, for prot, govern-

ment, and undergrad as control variables in

the regression. The omitted category includes

employment in the nonprot, nonacademic, non-

government sector, not currently employed,

or retired.

We base our inference on the estimated

coefcient on the binary indicator, female, in

the model,

y

i,j

=

j1

female

i

+

j2

PhD1970s

i

(1)

+

j3

PhD1980s

i

+

j4

PhD1990s

i

+

j5

PhD2000s

i

+

j6

graduate

i

+

j7

government

i

+

j8

for prot

i

+

j9

undergrad

i

+

j0

+

i,j

,

where i denotes the ith economist and j denotes

the jth question or group of questions. Because

we cannot observe the survey answers of those

economists who did not respond, even if the

regression error is independent of the control

variables, it is possible that estimation of

j1

using only the responders observations will

produce inconsistent and biased estimates of the

gender effect. We test the null hypothesis of no

selection bias using the Heckman (1979) two-

stage procedure.

We assume that the decision to respond

to the survey follows a probit model, P(s

i

=

1|x

i

) = P(Z x

i

), where s

i

= 1 if individual

MAY, MCGARVEY & WHAPLES: AEA MEMBERS VIEWS 117

TABLE 2

Probit Estimation of Probability of Response to

AEA survey, N = 391

X Variables Coefcients

Female 0.245

(0.136)

Graduate 0.684

(0.292)

Undergraduate 0.471 (0.308)

Government 0.528 (0.340)

For Prot 1.101

(0.399)

Listed Research 0.263

(0.149)

For Prot Listed Research 0.828

(0.388)

PhD1970s 0.075 (0.293)

PhD1980s 0.253 (0.289)

PhD1990s 0.444 (0.300)

PhD2000s 0.566

(0.314)

Constant 0.166 (0.0305)

Notes: Standard errors are in parentheses.

The symbols

,

,

denote 10%, 5%, 1% signicance

levels from testing the null hypothesis that the coefcient

equals 0.

i responds to the survey and s

i

= 0, if not. The

(1 k) vector of variables, x

i

, that inuences

the choice to respond to the survey includes

the control variables in Equation (1). We also

include a binary control for whether or not

the economist lists his/her research interests

in the AEA 2007 directory (listed research)

and the interaction of listed research with for

prot to allow the effect of listed research on

the probability of response to differ for those

working in the for-prot sector.

In this framework, the economist responds

to the survey (s

i

= 1) if the unobservable net

benet from doing so (s

i

) is positive, or if s

i

=

x

i

+u

i

> 0, where u

i

is a standard normal ran-

dom variable and is distributed independently of

x

i

. Under these assumptions, consistent estima-

tion of the gender effect on economists opin-

ions on question j (

j1

) can be obtained using

only the responders information if the error

term in Equation (1) is uncorrelated with u

i

,

the error term in the response equation. We test

the hypothesis that these errors have zero cor-

relation by adding the estimated inverse Mills

ratio, IMR

i

= pdf

z

(x

i

)/CDF

z

(x

i

) as a regres-

sor in Equation (1) and testing that its coefcient

equals 0.

Table 2 reports the probit estimates of the

response equation. The results indicate that the

probability of responding to the survey is lower

for female economists relative to males and for

economists employed in two of the included

job categories relative to males and those

who are retired or employed in nonacademic,

nongovernment, or for-prot institutions. Those

economists who earned their PhD in the 2000s

are more likely to respond to the survey, relative

to those who earned their degrees prior to 1970.

Those economists who list their current research

interest in the AEA directory are less likely to

respond; however, those who work in for-prot

institutions and list their current research are

more likely to respond.

Table 3 presents the ordinary least squares

estimation of Equation (1) for each of the

ve topic groups, with and without the inclu-

sion of the estimated inverse Mills ratio. The

dependent variable is the scaled response to

the questions on each topic, standardized to

have zero mean and unit variance, so that

the coefcient on female is the average dif-

ference in female economists response rela-

tive to male economists in standard deviation

units. The results indicate that male and female

U.S.-trained AEA members generally agree on

core economic precepts and methodology and

on U.S. environmental policy, but differ on

issues related to market solutions and govern-

ment intervention, government-backed redistri-

bution, and the extent of gender inequity in

the U.S. labor market and within the economics

profession.

Tests of the null hypothesis of no selection

bias for each topic category provide no evi-

dence that the selection equation error is corre-

lated with the error in Equation (1); moreover,

the inclusion of the inverse Mills ratio in the

regressions has little effect on the ordinary least

squares (OLS) point estimates and estimated

standard errors. These results support the valid-

ity of our study using the sample of responding

economists to estimate model (1) and suggest

that our inference on gender differences will not

suffer from selection bias.

III. GENDER DIFFERENCES IN ECONOMISTS

VIEWS ON POLICY ISSUES

This section presents Seeming Unrelated

Regression (SUR) estimation results based on

the survey response to estimate gender dif-

ferences in economists views on economic

methodology and policy issues. The SUR model

is relevant when the regression errors are cor-

related across equations and have different vari-

ances. For convenience, we reproduce our model

118 CONTEMPORARY ECONOMIC POLICY

T

A

B

L

E

3

R

e

g

r

e

s

s

i

o

n

T

e

s

t

s

o

f

N

o

S

e

l

e

c

t

i

o

n

B

i

a

s

U

s

i

n

g

T

w

o

-

S

t

e

p

H

e

c

k

m

a

n

P

r

o

c

e

d

u

r

e

(

H

e

c

k

i

t

)

D

e

p

e

n

d

e

n

t

V

a

r

i

a

b

l

e

:

S

t

a

n

d

a

r

d

i

z

e

d

S

c

a

l

e

d

A

n

s

w

e

r

t

o

G

r

o

u

p

Q

u

e

s

t

i

o

n

G

r

o

u

p

1

:

C

o

r

e

P

r

e

c

e

p

t

s

&

E

c

o

n

o

m

i

c

M

e

t

h

o

d

o

l

o

g

y

G

r

o

u

p

2

:

M

a

r

k

e

t

S

o

l

u

t

i

o

n

s

a

n

d

G

o

v

e

r

n

m

e

n

t

I

n

t

e

r

v

e

n

t

i

o

n

G

r

o

u

p

3

:

G

o

v

e

r

n

m

e

n

t

S

p

e

n

d

i

n

g

,

T

a

x

i

n

g

&

R

e

d

i

s

t

r

i

b

u

t

i

o

n

G

r

o

u

p

4

:

T

h

e

E

n

v

i

r

o

n

m

e

n

t

G

r

o

u

p

5

:

G

e

n

d

e

r

a

n

d

E

q

u

a

l

O

p

p

o

r

t

u

n

i

t

y

V

a

r

i

a

b

l

e

s

O

L

S

H

e

c

k

i

t

O

L

S

H

e

c

k

i

t

O

L

S

H

e

c

k

i

t

O

L

S

H

e

c

k

i

t

O

L

S

H

e

c

k

i

t

F

e

m

a

l

e

0

.

1

9

6

0

.

2

1

9

0

.

5

0

6

0

.

6

1

3

1

.

0

5

6

0

.

9

7

9

0

.

3

0

0

0

.

4

0

0

0

.

9

3

8

0

.

8

0

6

(

0

.

1

9

7

)

(

0

.

2

3

2

)

(

0

.

1

8

0

)

(

0

.

2

1

6

)

(

0

.

1

7

4

)

(

0

.

2

1

3

)

(

0

.

1

9

8

)

(

0

.

2

3

9

)

(

0

.

1

7

3

)

(

0

.

2

1

4

)

P

h

D

1

9

7

0

s

0

.

8

5

1

0

.

8

4

2

0

.

4

1

5

0

.

4

6

7

0

.

4

1

5

0

.

4

6

1

0

.

8

1

2

0

.

9

3

5

0

.

0

9

5

0

.

0

1

0

(

0

.

4

7

3

)

(

0

.

4

8

0

)

(

0

.

4

0

9

)

(

0

.

4

1

3

)

(

0

.

4

0

9

)

(

0

.

4

5

1

)

(

0

.

4

9

4

)

(

0

.

5

1

4

)

(

0

.

4

3

3

)

(

0

.

4

4

7

)

P

h

D

1

9

8

0

s

0

.

8

8

2

0

.

8

5

9

0

.

9

1

9

0

.

8

4

7

0

.

9

1

9

0

.

8

2

2

0

.

9

1

3

0

.

9

0

1

0

.

0

4

3

0

.

1

0

3

(

0

.

4

6

3

)

(

0

.

4

6

7

)

(

0

.

4

0

0

)

(

0

.

4

1

0

)

(

0

.

4

0

0

)

(

0

.

4

4

3

)

(

0

.

4

7

6

)

(

0

.

4

7

8

)

(

0

.

4

2

0

)

(

0

.

4

2

5

)

P

h

D

1

9

9

0

s

0

.

9

0

3

0

.

9

1

9

0

.

7

1

6

0

.

4

9

4

0

.

7

1

6

0

.

5

8

7

0

.

8

1

4

0

.

6

5

9

0

.

0

3

2

0

.

2

2

4

(

0

.

4

5

9

)

(

0

.

5

0

4

)

(

0

.

3

9

7

)

(

0

.

4

5

2

)

(

0

.

3

9

7

)

(

0

.

4

8

1

)

(

0

.

4

7

8

)

(

0

.

5

0

9

)

(

0

.

4

0

9

)

(

0

.

4

5

0

)

P

h

D

2

0

0

0

s

0

.

5

9

6

0

.

5

5

9

0

.

4

2

3

0

.

1

6

3

0

.

4

2

3

0

.

6

8

8

0

.

6

2

0

0

.

4

3

3

0

.

0

8

9

0

.

1

9

1

(

0

.

4

8

8

)

(

0

.

5

6

8

)

(

0

.

4

2

6

)

(

0

.

5

1

0

)

(

0

.

4

2

6

)

(

0

.

5

3

1

)

(

0

.

5

0

1

)

(

0

.

5

5

4

)

(

0

.

4

3

8

)

(

0

.

5

1

3

)

G

r

a

d

u

a

t

e

0

.

8

8

9

0

.

8

7

5

0

.

1

1

8

0

.

1

0

7

0

.

1

1

8

0

.

1

2

3

0

.

3

5

7

0

.

1

7

3

0

.

0

6

7

0

.

3

0

5

(

0

.

3

6

1

)

(

0

.

4

7

2

)

(

0

.

3

1

8

)

(

0

.

3

9

4

)

(

0

.

3

1

8

)

(

0

.

3

7

3

)

(

0

.

3

7

8

)

(

0

.

4

3

7

)

(

0

.

3

2

6

)

(

0

.

3

9

8

)

G

o

v

e

r

n

m

e

n

t

0

.

6

0

8

0

.

5

9

1

0

.

2

2

4

0

.

3

4

5

0

.

2

2

4

0

.

1

6

2

0

.

0

1

5

0

.

0

7

3

0

.

1

2

6

0

.

0

1

1

(

0

.

4

2

2

)

(

0

.

4

6

2

)

(

0

.

3

6

8

)

(

0

.

3

9

1

)

(

0

.

3

6

8

)

(

0

.

3

7

6

)

(

0

.

4

1

6

)

(

0

.

4

3

2

)

(

0

.

3

6

7

)

(

0

.

3

8

4

)

F

o

r

P

r

o

t

0

.

9

7

2

0

.

9

6

5

0

.

0

2

5

0

.

2

1

3

0

.

0

2

5

0

.

0

6

8

0

.

2

5

4

0

.

0

9

5

0

.

1

0

1

0

.

0

4

6

(

0

.

4

1

8

)

(

0

.

4

6

6

)

(

0

.

3

7

0

)

(

0

.

4

1

6

)

(

0

.

3

7

0

)

(

0

.

4

0

6

)

(

0

.

4

4

2

)

(

0

.

4

8

0

)

(

0

.

4

1

2

)

(

0

.

4

3

6

)

U

n

d

e

r

g

r

a

d

u

a

t

e

0

.

8

2

9

0

.

7

7

0

0

.

1

0

8

0

.

0

1

0

0

.

1

0

8

0

.

3

8

4

0

.

3

1

1

0

.

2

2

7

0

.

1

3

0

0

.

2

5

8

(

0

.

3

8

1

)

(

0

.

4

1

7

)

(

0

.

3

4

2

)

(

0

.

3

7

3

)

(

0

.

3

4

2

)

(

0

.

3

7

0

)

(

0

.

4

0

0

)

(

0

.

4

2

0

)

(

0

.

3

4

5

)

(

0

.

3

6

7

)

I

n

v

e

r

s

e

M

i

l

l

s

R

a

t

i

o

0

.

0

1

5

0

.

7

4

0

0

.

3

8

9

0

.

7

2

7

0

.

8

4

9

(

0

.

9

0

8

)

(

0

.

7

4

4

)

(

0

.

7

4

8

)

(

0

.

8

4

5

)

(

0

.

8

0

5

)

C

o

n

s

t

a

n

t

0

.

1

2

2

0

.

1

1

7

0

.

7

6

4

0

.

1

0

9

0

.

7

6

4

1

.

2

9

6

0

.

6

2

8

0

.

0

0

8

0

.

4

0

3

1

.

1

4

7

(

0

.

3

6

7

)

(

0

.

8

4

6

)

(

0

.

3

2

0

)

(

0

.

7

3

0

)

(

0

.

3

2

0

)

(

0

.

7

7

1

)

(

0

.

3

7

4

)

(

0

.

8

0

9

)

(

0

.

3

2

1

)

(

0

.

7

7

5

)

R

2

0

.

0

9

9

0

.

1

0

6

0

.

1

5

5

0

.

1

6

0

0

.

3

0

6

0

.

3

0

6

0

.

0

6

7

0

.

0

7

2

0

.

2

1

8

0

.

2

1

4

N

1

1

3

1

1

2

1

2

3

1

2

2

1

1

4

1

1

3

1

1

7

1

1

6

1

2

0

1

1

9

N

o

t

e

s

:

S

t

a

n

d

a

r

d

e

r

r

o

r

s

a

r

e

i

n

p

a

r

e

n

t

h

e

s

e

s

b

e

n

e

a

t

h

c

o

e

f

c

i

e

n

t

p

o

i

n

t

e

s

t

i

m

a

t

e

s

.

T

h

e

s

y

m

b

o

l

s

d

e

n

o

t

e

1

0

%

,

5

%

,

1

%

s

i

g

n

i

c

a

n

c

e

l

e

v

e

l

s

f

r

o

m

t

e

s

t

i

n

g

t

h

e

n

u

l

l

h

y

p

o

t

h

e

s

i

s

t

h

a

t

t

h

e

p

o

p

u

l

a

t

i

o

n

c

o

e

f

c

i

e

n

t

e

q

u

a

l

s

0

.

MAY, MCGARVEY & WHAPLES: AEA MEMBERS VIEWS 119

of economist is response to question j (or topic

j) from the previous section,

y

i,j

=

j1

female

i

+

j2

PhD1970s

i

(2)

+

j3

PhD1980s

i

+

j4

PhD1990s

i

+

j5

PhD2000s

i

+

j6

graduate

i

+

j7

government

i

+

j8

for prot

i

+

j9

undergrad

i

+

j0

+

i,j

,

where we treat equation j as part of a SUR

system of equations. The error terms represent

those unobservable individual-specic factors

that affect opinions but are unrelated to gen-

der, decade in which the PhD is earned, and

type of employment. We allow the variances of

the errors to differ by question, the errors to be

correlated across questions, and the error covari-

ance matrices to differ for males and females.

The generalized least squares (GLS) method

increases the precision of our estimates by incor-

porating the estimated relationship among unob-

servable factors that form opinions on related

topics.

Our rst estimation strategy is to measure

gender differences in economists views on gen-

eral issues addressed by the ve groups of sur-

vey questions. This provides a more precise

measure of opinion on the issue by incorporating

repeated observations on the same topic (aver-

aging an individuals answers to all questions

within the group topic), but limits the sample to

individuals who answered all questions within

the ve groups. Our second strategy is to esti-

mate the extent of gender differences in average

responses to specic questions within a general

topic area. The dependent variable is individual

is response to question j. Although y

i,j

is a

less precise estimate of individual is opinion

(it is based on the response to only one question

rather than an average of repeated responses on

a topic), the sample size increases to the num-

ber of economists who answered all questions

in one group rather than all groups.

A. Views on General Topic Areas

The rst SUR system explains the standard-

ized, scaled answers that measure the deviations

from the average economists views on the ve

topics: core precepts and economic methodology;

market solutions and government intervention;

government spending, taxing, and redistribu-

tion; U.S. environmental policies; and gender

and equal opportunity. The optimal weighting

scheme incorporated in the GLS systems estima-

tion increases the efciency of the estimates over

the OLS method. The number of observations,

however, is smaller for the systems estimation

because it is based on the number of economists

that have complete information for all questions

in each of the ve groups.

Table 4 contains the GLS estimates of the

coefcients in Equation (1) for j = 1, 2, . . . ,5,

corresponding to the ve group topics. The

dependent variables are the scaled responses,

standardized to have zero mean and unit vari-

ance, so the coefcient on a binary control vari-

able (female, employment category, or decade

of PhD) is the average difference (in standard

deviation units) in the response of economists

who fall into the respective category relative to

those in the omitted category, given the other

controls. The GLS system results conrm the

conclusions based on the OLS and Heckit esti-

mates of Table 3. Male and female members of

the AEA with doctoral degrees from U.S. insti-

tutions appear to agree on core precepts and eco-

nomic methodology, whereas female economists

tend to favor government-backed redistribution

policies more than males, view gender inequality

as a problem in the U.S. labor market and eco-

nomics profession more than males, and favor

government intervention over market solutions

more than their male counterparts. The mean

gender differences in opinions on these topics

are relatively large. The mean views of women

economists on government spending, taxing,

and redistribution and on gender inequality are

both approximately one standard deviation away

from the mean opinion of male economists.

Although the divergence in magnitudes of the

GLS and OLS estimated gender difference in

opinion on U.S. environmental policies is not

large, the GLS estimate is statistically signi-

cant. The mean response of female economists

is about .45 standard deviations greater than the

mean male response, indicating that women tend

to favor an increase in U.S. environmental pro-

tection more than men.

Generally speaking, the demographic con-

trols contribute little to explaining views on

the ve group topics once one controls for

the economists gender.

5

The economists place

of employment appears to have no effect on

opinion once gender and degree vintage are

5. The joint null hypotheses that the coefcients on

PhD1970s, PhD1980s, PhD1990s, PhD2000s, Graduate,

Government, Forprot, and Undergrad equal 0 cannot be

rejected for each of the ve equations in the system.

120 CONTEMPORARY ECONOMIC POLICY

T

A

B

L

E

4

G

L

S

S

y

s

t

e

m

E

s

t

i

m

a

t

i

o

n

o

f

R

e

s

p

o

n

s

e

s

t

o

S

u

r

v

e

y

Q

u

e

s

t

i

o

n

s

S

t

a

n

d

a

r

d

i

z

e

d

(

M

=

0

,

S

D

=

1

)

S

c

a

l

e

d

A

n

s

w

e

r

s

t

o

G

r

o

u

p

Q

u

e

s

t

i

o

n

s

N

=

8

3

Q

u

e

s

t

i

o

n

G

r

o

u

p

F

e

m

a

l

e

P

h

D

1

9

7

0

s

P

h

D

1

9

8

0

s

P

h

D

1

9

9

0

s

P

h

D

2

0

0

0

s

G

r

a

d

u

a

t

e

G

o

v

e

r

n

m

e

n

t

F

o

r

P

r

o

t

U

n

d

e

r

g

r

a

d

u

a

t

e

C

o

n

s

t

a

n

t

G

r

o

u

p

1

:

c

o

r

e

p

r

e

c

e

p

t

s

/

e

c

o

n

o

m

i

c

m

e

t

h

o

d

o

l

o

g

y

(

6

q

u

e

s

t

i

o

n

s

;

C

r

o

n

b

a

c

h

=

.

7

1

)

0

.

2

7

1

.

2

0

0

.

8

6

0

.

0

8

4

0

.

6

0

0

.

8

6

0

.

2

6

0

.

8

4

0

.

3

5

0

.

3

5

(

0

.

2

3

)

(

0

.

5

4

)

(

0

.

5

1

)

(

0

.

5

1

)

(

0

.

5

5

)

(

0

.

4

1

)

(

0

.

4

7

)

(

0

.

4

7

)

(

0

.

4

4

)

(

0

.

4

3

)

G

r

o

u

p

2

:

m

a

r

k

e

t

s

o

l

u

t

i

o

n

s

a

n

d

g

o

v

e

r

n

m

e

n

t

i

n

t

e

r

v

e

n

t

i

o

n

s

(

8

q

u

e

s

t

i

o

n

s

;

C

r

o

n

b

a

c

h

=

.

7

8

)

0

.

6

5

0

.

7

7

1

.

0

1

0

0

.

8

7

2

0

.

6

7

0

.

3

5

0

.

2

3

0

.

1

8

0

.

0

7

0

.

9

1

(

0

.

2

3

)

(

0

.

5

2

)

(

0

.

4

9

)

(

0

.

4

9

)

(

0

.

5

3

)

(

0

.

3

9

)

(

0

.

4

6

)

(

0

.

4

6

)

(

0

.

4

3

)

(

0

.

4

1

)

G

r

o

u

p

3

:

g

o

v

e

r

n

m

e

n

t

s

p

e

n

d

i

n

g

,

t

a

x

i

n

g

,

&

r

e

d

i

s

t

r

i

b

u

t

i

o

n

(

9

q

u

e

s

t

i

o

n

s

;

C

r

o

n

b

a

c

h

=

.

9

2

)

0

.

9

1

0

.

7

8

0

.

8

3

1

0

.

6

3

0

.

7

3

0

.

2

6

0

.

1

9

0

.

1

0

0

.

2

9

0

.

8

8

(

0

.

2

2

)

(

0

.

5

1

)

(

0

.

4

8

)

(

0

.

4

8

)

(

0

.

5

2

)

(

0

.

3

8

)

(

0

.

4

5

)

(

0

.

4

5

)

(

0

.

4

2

)

(

0

.

4

0

)

G

r

o

u

p

4

:

t

h

e

e

n

v

i

r

o

n

m

e

n

t

(

4

q

u

e

s

t

i

o

n

s