Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Main Engine Third Stage Voskhod Launch Vehicle 18

Caricato da

Junior Miranda0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

38 visualizzazioni6 pagineVoskhod

Titolo originale

Voskhod 1

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

DOCX, PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoVoskhod

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato DOCX, PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

38 visualizzazioni6 pagineMain Engine Third Stage Voskhod Launch Vehicle 18

Caricato da

Junior MirandaVoskhod

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato DOCX, PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 6

1

October 12: Launch!

Final preparations for the launch of Voskhod were clouded by a failure

during test firing of the main engine similar to the one installed on third

stage of the Voskhod launch vehicle. However the culprit was quickly

traced to the ground test equipment. (18)

On October 9, Komarov, Feoktistov and Yegorov conducted their final

familiarization training inside of their future home in orbit and by the

end of the same day, the State Commission set the launch for October

12, 1964, at 10:30 Moscow Time. (231) On October 11, the rocket with

the spacecraft was rolled out to the launch pad. During final tests on

the pad, the troublesome Tral telemetry system failed again. Engineers

scrambled to replace it on the launch pad. The incident apparently

triggered one of Korolev's famous outbursts, this time directed at the

system's main developer Aleksei Bogomolov. (18)

On the eve of the flight, Feoktistov slept well and final preparations for

launch ran smoothly. On the morning of October 12, the crew woke up

in good, business-like spirit, Feoktistov remembered. As all three

climbed to the top of the launch gantry, Feoktistov caught a glimpse of

a huge junkyard of rocket debris, which accumulated over the past

seven years from various launch accidents in the vicinity of the launch

pad. However even that grim reminder could not sour Feoktistov's

excitement for the upcoming mission. Still, as they squeezed into their

tiny compartment and went through long wait for the liftoff, doubts

about the reliability of the rocket booster creped back into Feoktistov's

mind.

The 11A57 launch vehicle with the 3KV spacecraft blasted off from

NIIP-5 near Tyuratam on Oct. 12, 1964, at 10:30:01 Moscow Time,

with Vladimir Komarov, Konstantin Feoktistov and Boris Yegorov

onboard. Following the exhilarating 523-second climb uphill, the third

stage of the rocket flawlessly released the Voskhod into orbit. For the

first time, space travelers could share their impressions with each other

in the cabin of an orbiting ship. Feoktistov felt some discomfort and

realized that their short-term simulations of weightlessness on an

aircraft were far from realistic. He also realized extremely cramped

conditions inside the spacecraft, yet when he needed to get a camera,

he unbuckled and was able to turn around and get it from under his

seat. The crew's first of two workdays in space turned out to be very

hectic. They struggled with their minute-by-minute flight program even

during training and now found it even more difficult to keep up with the

tight schedule. (196)

2

During the mission, Komarov piloted and oriented the spacecraft in

space, while Feoktistov had responsibility for observations and

photography of the Earth, as well as the work with the sextant, an

experiment studying the behavior of the liquid in weightlessness,

monitoring and recording characteristics of newly installed ion sensors

relative to the velocity vector of the spacecraft. All these responsibilities

left Feoktistov little time for sleep. Still, the crew was able to fulfill a

lot: cosmonauts took several hundred photos of the Earth's surface,

hurricanes, clouds and ice sheets, sunsets and sunrises, the Sun and

the horizon. The crew was able to discern several layers of the

atmosphere with different levels of brightness, which could help to

provide more accurate angular elevation of stars over the horizon, if it

would be necessary to determine the ship's exact position in space.

As they soared in darkness over the night side of the Earth,

cosmonauts noticed a shiny layer at altitudes of 80 or 100 kilometers

above the Earth surface. Feoktistov interpreted it as cirrus clouds or

aerosols lit by the lunar light.

When the spacecraft reached its southernmost points at 65 degrees

latitude, the crew was treated with a fantastic light show of Aurora

Borealis. Their entire field of view was filled with yellow pillars of light

emanating from the white line above the horizon, towering to a height

of several hundred kilometers and spanning 20 or 30 kilometers across.

As the morning approached, the lights faded and disappeared. The

show replayed for crew during two more orbits.

Feoktistov conducted experiments with liquid and photographed the

results. The experiment was built as a pair of connected transparent

spheres containing liquid and gas. The cosmonaut was expected to

shake the unit and document how liquid and gas behave. When

Feoktistov was setting up the experiment, he discovered that the unit

had already been shaken up, probably during the launch. Water and

gas had already mixed and were not in hurry to separate.

With the help of Komarov, Feoktistov recorded characteristics from ion

sensors. While they recorded the data, Feoktistov noticed strange rays

on the monitor connected to the external camera. He photographed the

mysterious lines on the screen but the effect was later traced to

sunlight bouncing off the camera.

In the meantime, Yegorov conducted his medical studies. To the

surprise of his crew mates, Yegorov succeeded with most of his

program of taking blood samples, measuring pressure and pulse.

Fall of Khrushchev

3

Although Voskhod successfully began its historic mission, the Kremlin

officials in Moscow apparently "forgot" to make a traditional phone call

to Khrushchev, who went on an ill-fated holiday in Pitsunda on the

Black Sea. Worried about the progress of the mission, the Soviet leader

himself called Leonid Smirnov and harshly reprimanded him for not

delivering the news. It could be the first clue for Khrushchev that the

Kremlin plot which would topple him from power in less than 24 hours

had already been in motion. However, Khrushchev apparently

suspected nothing and made a congratulatory phone call to the

Voskhod crew.

When the sensational news about the three-man Voskhod reached

America, US official reportedly called the new Soviet spacecraft a

prototype of the 'space cruiser.' Korolev's engineers, of course, knew

better. "We wished it was true," wrote Boris Chertok. (466)

As their first work day in orbit had come to an end, cosmonauts had

dinner from their toothpaste-like containers. They also "went to bed" in

shifts. Because Yegorov was getting cold (as he believed from the

window), Feoktistov let him to take his middle seat, while Feoktistov

took the "night shift" during mostly "deaf orbits", when the spacecraft

was out-of-range of mission control. He spent most of the time peering

into the window. (196)

A summary of crew activities on October 12:

Orbit 1: Medical checks (Yegorov); breakfast;

Orbit 2: Greetings to the participants of the Tokyo Olympics;

Orbit 3-4: Physical tests: blood samples, blood pressure

measurements, cognitive tests;

Orbit 4: Lunch;

Orbit 5: Sleep period (Komarov); Observations of the Earth surface and

the atmosphere (Feoktistov); Vestibular tests (Yegorov, Feoktistov);

Orbit 6: Manual attitude control exercise (Komarov);

Orbit 7-8: TV conference with ground control;

Orbit 9-13: Voskhod is out communications range; Sleep period;

Orbit 14: Transmission of orbital parameters to ground control;

receiving input for manual control in case of automated landing system

failure;

Orbit 15: Manual attitude control exercise (Komarov); Horizon

photography (Feoktistov), Sleep period (Yegorov). (231)

October 13: Landing in the coup

4

As his colleagues woke up, the hectic program of observations and

communications had resumed. Feoktistov told his crew mates about his

conversation with Korolev and proposed his commander to make another

"official" request to extend the flight. Without much enthusiasm, Komarov

made a call and was rebuffed as well. (Clearly, the crew and ground

controllers were worrying about potential problems during the upcoming

braking maneuver and wanted to give the overstretched mission maximum

backup opportunities). In preparation for landing, the trio cosmonauts

signed a photo for Korolev, dated Oct. 13, 06:50 (Moscow Time). (253)

The automated attitude control system came to life at 09:55:39 Moscow

Decree Time, during the 16th orbit of the mission, and successfully placed

the spacecraft tail first for a braking maneuver. Voskhod fired its braking

engine as scheduled at 10:18:58 Moscow Time, as it was zooming toward

the coast of Africa over the Gulf of Guinea. (231) Then, the service module

separated from the descent capsule. The ball-shaped crew cabin flipped

around and cosmonauts saw their tumbling service module nearby. As

Feoktistov peered outside, his window was suddenly sprayed with liquid

escaping from the drainage of the propulsion system in the service module

after the braking maneuver. Immediately, the window was covered with

frost. The ice melted away only after entering the atmosphere, but soon

again, nothing could be seen through the bright light of plasma

surrounding the capsule. Cosmonauts started hearing loud flops sounding

like gun shots. Komarov and Yegorov looked puzzled at Feoktistov who

tried to explain the phenomenon by sharp pressure changes in the burning

ablative layers of the thermal protection system.

Understandably, the crew had some anxiety about their new parachutes

and the rocket-powered landing system. The soft-landing engines had to

be activated by a rather tenuous probe and Feoktistov was now worrying

whether the probe could deploy prematurely and burn up during the

reentry. (196) In the meantime, officials on the ground had their own fears

since no radio messages had come from the spacecraft during its entire

descent. Reports from Dolinsk and Krasnodar tracking ships at 10:25

Moscow Time confirming the on-time braking engine firing provided only

limited comfort.

Finally, the pilot of the Ilyushin-14 search aircraft spotted the Voskhod

descending under a parachute and after an anxious inquiry from mission

control confirmed that both parachutes had been deployed.

5

As Feoktistov remembered, the landing was so "soft" that "sparks were

flying from (their) eyes." The capsule then rolled over and came to rest

with cosmonauts hanging on their seat belts from the "ceiling." Komarov,

who was sitting next to the hatch, got out first, followed by Yegorov and,

finally, by Feoktistov. The first space trio was in good shape. (196)

The crew of the rescue plane circling over the landing site then reported

seeing three people waving their hands next to the capsule. Naturally, the

officials at mission control had a huge sigh of relief.

According to the official sources, the spacecraft landed as planned on

October 13, 1964, at 10:47 Moscow Time. (253) The descent module

touched down 312 kilometers northeast of city of Kustanai (now Kostanai)

in Kazakhstan. The flight lasted for 24 hours, 17 minutes 3 seconds. (2,

52) The mission completed 16 revolutions around the Earth and covered

700,000 kilometers. (509)

The crew first traveled to Kustanai, where they were waiting for a planned

congratulatory phone call from Khrushchev. However by 3 p.m. Leonid

Smirnov called and informed Kamanin that the conversation would not take

place and the crew should return to the launch site. (18)

By the end of the day, the crew flew to Tyuratam, apparently on the same

Ilyushin-18 aircraft that would crash in Yugoslavia just five days later.

Upon arrival to the launch site, the cosmonauts were accommodated at

their familiar quarters at Site 17. They expected to fly to Moscow the next

day, however were told to have another day of rest and post-flight medical

checks.

On October 14, at the expanded session of the State Commission, the crew

reported about their flight. The event was concluded with an official dinner.

By the evening, the Air Force commander Vershinin called from Moscow

and told his deputy Rudenko to return to the capital. Next day, Korolev and

Tyulin also hastily departed for Moscow without any explanations. The crew

spent time hunting and watching movies. (18) When they finally enquired

what was going on and why all the delays, officials told them that "the

address is being straightened out." Puzzled cosmonauts were finally

explained that Vladimir Komarov would have to make a post-flight address

to a new leader in the Kremlin, since Nikita Khrushchev had been

dismissed in a bloodless coup and Leonid Brezhnev took power in the

USSR! As Feoktistov later said in his memoirs, "naive Khrushchev forgot

6

that a dictator can not afford even for a minute to relax his grip over the

police, army and his associates." (196)

The crew was finally invited back to Moscow on October 19, where they

were greeted by Leonid Brezhnev, instead of Khrushchev who had forever

disappeared from the public view. On a plane to Moscow, one joker

"advised" Komarov to slightly edit a traditional greeting of cosmonauts to

Brezhnev to a following: "...We are ready to fulfill any new assignment

from any new government." Still, trying not to break traditions of the

Khrushchevean era, Brezhnev treated cosmonauts with a big parade on the

Red Square and a huge reception in the Kremlin. (18) However, for the

Soviet people, a new era had began, which would last for almost quarter of

a century.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Vostok 1 - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocumento11 pagineVostok 1 - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopediad_richard_dNessuna valutazione finora

- Voskhod 1's historic multi-crew space missionDocumento11 pagineVoskhod 1's historic multi-crew space missionjackie_fisher_email8329100% (1)

- Thirteen: The Apollo Flight That FailedDa EverandThirteen: The Apollo Flight That FailedValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (35)

- VostokDocumento22 pagineVostokpem tigaNessuna valutazione finora

- Chariots for Apollo: The NASA History of Manned Lunar Spacecraft to 1969Da EverandChariots for Apollo: The NASA History of Manned Lunar Spacecraft to 1969Valutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (4)

- Man on the Moon: How a Photograph Made Anything Seem PossibleDa EverandMan on the Moon: How a Photograph Made Anything Seem PossibleValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (2)

- Vladimir Komarov Last Words Transcript PDFDocumento10 pagineVladimir Komarov Last Words Transcript PDFElena Silvia SoldeanuNessuna valutazione finora

- A Much Unsung Hero, The Lunar Landing Training Vehicle: And Other NASA RecollectionsDa EverandA Much Unsung Hero, The Lunar Landing Training Vehicle: And Other NASA RecollectionsValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- Third Generation Soviet Space Systems - Multi-Echelon Antiballistic Missile System - PolyusDocumento6 pagineThird Generation Soviet Space Systems - Multi-Echelon Antiballistic Missile System - Polyusjb2ookworm100% (1)

- Nasa Secret Files: From Sex In Space to Alien EncountersDa EverandNasa Secret Files: From Sex In Space to Alien EncountersNessuna valutazione finora

- Proekt Po V V I DDocumento5 pagineProekt Po V V I DArtemNessuna valutazione finora

- Extravehicular ActivityDocumento9 pagineExtravehicular ActivityAnonymous 4FVm26mbcONessuna valutazione finora

- Venera-9's Panoramic Views of Venusian SurfaceDocumento8 pagineVenera-9's Panoramic Views of Venusian SurfaceCatherine Hearts YhooNessuna valutazione finora

- To Fall From Space Parachutes and The Space ProgramDocumento29 pagineTo Fall From Space Parachutes and The Space ProgramBob Andrepont100% (1)

- Spacecraft: "Orbiter" Redirects Here. For Other Uses, See - "Orbital Vehicle" Redirects Here. For Other Uses, SeeDocumento9 pagineSpacecraft: "Orbiter" Redirects Here. For Other Uses, See - "Orbital Vehicle" Redirects Here. For Other Uses, SeeJaneeshVargheseNessuna valutazione finora

- Epic Rivalry: Inside the Soviet and American Space RaceDa EverandEpic Rivalry: Inside the Soviet and American Space RaceValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (32)

- Advances in Space Science and TechnologyDa EverandAdvances in Space Science and TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Space Exploration History Lecture OneDocumento10 pagineSpace Exploration History Lecture OneKiran RajuNessuna valutazione finora

- Notable Achievements in Aviation and Aerospace TechnologyDocumento122 pagineNotable Achievements in Aviation and Aerospace TechnologyYuryNessuna valutazione finora

- Near-Earth Objects: Finding Them Before They Find UsDa EverandNear-Earth Objects: Finding Them Before They Find UsValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (6)

- Apollo 11 5th Anniversary Press KitDocumento86 pagineApollo 11 5th Anniversary Press KitBob AndrepontNessuna valutazione finora

- Pilot and Cosmonaut Pavel Popovich and UFOs - Openminds - TVDocumento13 paginePilot and Cosmonaut Pavel Popovich and UFOs - Openminds - TVoglasifwdNessuna valutazione finora

- Apollo-Soyuz Test ProjectDocumento122 pagineApollo-Soyuz Test ProjectAviation/Space History LibraryNessuna valutazione finora

- BuranDocumento26 pagineBuranMorcheebaNessuna valutazione finora

- More Space FactsDocumento4 pagineMore Space Factszabolotnyi61Nessuna valutazione finora

- RSP NotesDocumento74 pagineRSP NotesSagar Bhandari100% (1)

- Luna 9Documento7 pagineLuna 9Junior MirandaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Soviet Programme in A NutshellDocumento217 pagineThe Soviet Programme in A NutshellmainakbasuNessuna valutazione finora

- Intense Tropical Cyclone Berguitta1Documento13 pagineIntense Tropical Cyclone Berguitta1Cielo Janine VelasquezNessuna valutazione finora

- Breaking into Cosmos: The Story of SputnikDocumento82 pagineBreaking into Cosmos: The Story of Sputnikadpr7Nessuna valutazione finora

- Space RaceDocumento3 pagineSpace Racezabolotnyi61Nessuna valutazione finora

- Canadarm and Collaboration: How Canada’s Astronauts and Space Robots Explore New WorldsDa EverandCanadarm and Collaboration: How Canada’s Astronauts and Space Robots Explore New WorldsNessuna valutazione finora

- Getting A Feel For Braille: Swallowed-Up Solar Systems?Documento2 pagineGetting A Feel For Braille: Swallowed-Up Solar Systems?birbiburbiNessuna valutazione finora

- Ground-Based Telescopic ResearchDocumento2 pagineGround-Based Telescopic ResearchAminath MeesanNessuna valutazione finora

- Manned Mars Landing: Presentation to the Space Task Group - 1969Da EverandManned Mars Landing: Presentation to the Space Task Group - 1969Nessuna valutazione finora

- Apollo-Soyuz Test ProjectDocumento15 pagineApollo-Soyuz Test ProjectJoesph BlackNessuna valutazione finora

- Apollo 11: First Moon LandingDocumento6 pagineApollo 11: First Moon LandingirfanmNessuna valutazione finora

- Beyond: The Astonishing Story of the First Human to Leave Our Planet and Journey into SpaceDa EverandBeyond: The Astonishing Story of the First Human to Leave Our Planet and Journey into SpaceValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (22)

- Conquest of SpaceDocumento18 pagineConquest of Spacezubig4Nessuna valutazione finora

- Spaceflight: From Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocumento35 pagineSpaceflight: From Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopediamanoj kumar rout100% (2)

- FirtsmaninspaceDocumento3 pagineFirtsmaninspaceanakui14Nessuna valutazione finora

- Try_AI_on_one_of_our_notes_take_off_like_Apollo_11Documento16 pagineTry_AI_on_one_of_our_notes_take_off_like_Apollo_11yordaniymami19911012Nessuna valutazione finora

- Pioneer 10: Robotic Space ProbeDocumento4 paginePioneer 10: Robotic Space ProbeMark Milo AsugNessuna valutazione finora

- Space Activity Impact on Science and Technology: Proceedings of the XXIVth International Astronautical Congress, Baku, USSR, 7–13 October, 1973Da EverandSpace Activity Impact on Science and Technology: Proceedings of the XXIVth International Astronautical Congress, Baku, USSR, 7–13 October, 1973L.G. NapolitanoNessuna valutazione finora

- Spaceflight101 Com Spacerockets Long March 7Documento30 pagineSpaceflight101 Com Spacerockets Long March 7Junior MirandaNessuna valutazione finora

- NASA Astronauts On Soyuz Experience and Lessons For The FutureDocumento42 pagineNASA Astronauts On Soyuz Experience and Lessons For The FutureBob AndrepontNessuna valutazione finora

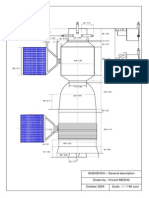

- SHENZHOU - General DescriptionDocumento1 paginaSHENZHOU - General DescriptionJunior MirandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Ballistic Missiles and Missile Defense in AsiaDocumento84 pagineBallistic Missiles and Missile Defense in AsiaJunior MirandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Shenzhou 4Documento1 paginaShenzhou 4Junior MirandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Turbo 2Documento1 paginaTurbo 2Junior MirandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Shenzhou 3Documento1 paginaShenzhou 3Junior MirandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Vs-40 Sounding RocketDocumento5 pagineVs-40 Sounding RocketJunior MirandaNessuna valutazione finora

- SHENZHOU - Shroud ConfigurationDocumento1 paginaSHENZHOU - Shroud ConfigurationJunior MirandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Shenzhou 2Documento1 paginaShenzhou 2Junior MirandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Expedition 14 Press KitDocumento118 pagineExpedition 14 Press KitUhrin ImreNessuna valutazione finora

- Ambitious Goal of Sergei KorolevDocumento5 pagineAmbitious Goal of Sergei KorolevJunior MirandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Isometric Drawings Guide in <40 CharactersDocumento6 pagineIsometric Drawings Guide in <40 CharactersSiva KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- A Better Focus On ShenzhouDocumento4 pagineA Better Focus On ShenzhouJunior MirandaNessuna valutazione finora

- "Kurs" Radio Engineering SystemDocumento2 pagine"Kurs" Radio Engineering SystemJunior MirandaNessuna valutazione finora

- ColunaDocumento1 paginaColunaJunior MirandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Energia Blok YaDocumento5 pagineEnergia Blok YaJunior MirandaNessuna valutazione finora

- 2.8isometric ViewDocumento9 pagine2.8isometric ViewSiva KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Energia Blok YaDocumento5 pagineEnergia Blok YaJunior MirandaNessuna valutazione finora

- SaluytbakDocumento1 paginaSaluytbakJunior MirandaNessuna valutazione finora

- F-1 EngineDocumento11 pagineF-1 EnginentschkeNessuna valutazione finora

- Shenzhou - SinoDefenceDocumento10 pagineShenzhou - SinoDefenceJunior MirandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Angara A5Documento16 pagineAngara A5Junior MirandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Buran 2Documento4 pagineBuran 2Junior MirandaNessuna valutazione finora

- All International Space Station Missions: Spacecraft Launch Landing/ Deorbit Mission Mission Crew 1998Documento10 pagineAll International Space Station Missions: Spacecraft Launch Landing/ Deorbit Mission Mission Crew 1998Junior MirandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Shenzhou - SinoDefenceDocumento10 pagineShenzhou - SinoDefenceJunior MirandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Orion's 8 Key EFT-1 Test Flight Events ExplainedDocumento6 pagineOrion's 8 Key EFT-1 Test Flight Events ExplainedJunior MirandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Orion's 8 Key EFT-1 Test Flight Events ExplainedDocumento6 pagineOrion's 8 Key EFT-1 Test Flight Events ExplainedJunior MirandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Delta IV Launch Services UserDocumento1 paginaDelta IV Launch Services UserJunior MirandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Solar ProbesDocumento27 pagineSolar ProbesJunior MirandaNessuna valutazione finora