Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

CC6D - 1 - Haematuria-Nat Path Group Guideline

Caricato da

Sheral Aida0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

15 visualizzazioni3 paginemedicine

Titolo originale

CC6D_1_Haematuria-Nat Path Group Guideline

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentomedicine

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

15 visualizzazioni3 pagineCC6D - 1 - Haematuria-Nat Path Group Guideline

Caricato da

Sheral Aidamedicine

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 3

Page 1 of 3 Page 1 of 3

National Pathology Group June 2003

National Pathology Group June 2003

Guideline for:

THE INVESTIGATION OF HAEMATURIA THE INVESTIGATION OF HAEMATURIA

Definition

Haematuria is defined as the excretion of intact or partially damaged erythrocytes

in the urine in quantities that exceed a population-derived threshold of normal i.e

>3 red blood cells per HPF of centrifuged urine

or

>8000 red blood cells per ml of uncentrifuged urine

Haematuria should be considered a symptom of serious disease until proved other-

wise.

Haematuria can present as:

Gross haematuria usually uroepithelial in origin.

Microscopic haematuria is defined as the excretion of more than 3 red blood

cells / HPF in the centrifuged sample or >8000 red blood cells per ml of uncen-

trifuged urine usually nephritic in origin

Positive dipstick false positive results may occur when the urine contains povi-

done or hypochlorite. The dipstick has false-negative rates of up to 18%, and it

is therefore prudent not to rely on the dipstick when specifically searching for

haematuria e.g. unexplained flank mass, urinary symptoms, oedema. In such

cases, urine for microscopic examination is always warranted.

Initial laboratory investigations

A clean-catch midstream urine specimen for urinalysis, including microscopy and culture, should

be obtained using aseptic technique to avoid contamination from the genitalia.

Microscopic examination of the urine is essential to confirm the diagnosis, but it is also necessary

to examine the red cells for dysmorphia, and urine for casts.

Microscopic differentiation of the RBCs into dysmorphic or isomorphic (normal) can assist in differ-

entiating between glomerular- and nonglomerular sources of bleeding and hence guide further

investigation. Automated flow cytometry (FBC machines) of urine is a more accurate method

than microscopy to differentiate glomerular from nonglomerular haematuria, based on the size of

the red blood cells. The urinary red cells in glomerular haematuria are smaller than normal (<70

fl; microcytic).

Once categorized, investigate the haematuria further according to the suspected site of origin

(glomerular vs nonglomerular).

Both glomerular- and nonglomerular haematuria patients should have the following baseline

blood tests:

FBC, ESR U&E, creatinine Protein profile

Cholesterol Calcium, phosphorus ALT

Alkaline phosphatase Uric acid Blood glucose

In glomerular haematuria (i.e. microcytic or dysmorphic red blood cells, heavy proteinuria, red-

cell casts), search for primary and secondary causes by using the history, physical examination,

and selected laboratory tests which include:

ANF, anti-DNA Hepatitis B surface antigen

ASO titre Complement components C3 and C4

Non-glomerular haematuria: Further urological investigation, including renal and bladder ultra-

sonography, IVP, excretory urography, and cystourethroscopy, if more than 3 RBCs/HPF are

found in at least 2 or 3 properly collected urine samples and the red blood cells are isomorphic

and normocytic, or if gross haematuria (>100 RBCs/HPF) is found on a single urinalysis.

Other studies include: CT scanning, Renal angiography, Ureterorenoscopy, Renal biopsy

Page 2 of 3 Page 2 of 3

National Pathology Group June 2003

National Pathology Group June 2003

CAUSES

SPECIFIC LABORATORY TESTS

Glomerular haematuria

1 Primary

Renal biopsy

IgA nephropathy (Bergers disease)

Mesangial proliferative gn.

Membranoprofilerative gn.

Crescentic gn.

Focal gn.

Membranous gn.

Fibrillary gn.

Minimal change disease

2. Multisystem disease

Renal biopsy

Lupus nephritis ANF, anti-DNA, anti-ENA

Rheumatoid vasculitis

Rheumatoid factor

Wegeners granulomatosis

ANCA

Goodpastures syndrome

3. Infections

Postinfectious glomerulonephritis ASO titers and anti-DNaseB

Infective endocarditis Blood cultures

Bacterial pneumonia

Viral hepatitis Hepatitis A, B and C serology

HIV infection HIV antibodies

Malaria Malaria smears, antigen and QBC

Syphilis Syphilis serology

4. Hereditary disease

Alports syndrome

Fabrys disease

Thin basement membrane nephropa-

5. Other

Drug-induced nephropathy e.g.

NSAIDS

Aspirin

Captopril

Cephalosporins

Penicillins

Ciprofloxacin

Diabetic nephropathy

Malignant hypertension

Blood glucose

Page 3 of 3 Page 3 of 3

National Pathology Group June 2003

National Pathology Group June 2003

CAUSES SPECIFIC LABORATORY TESTS

Nonglomerular haematuria

Renal calcul

Renal biopsy

Uroepithelial tumours esp.

Urine cytology

Renal cell carcinoma

Wilmstumour

Metastatic tumours

Bladder carcinoma Urine NMP-22 this involves the quantitative detec-

tion of a specific nuclear matrix protein. This assay of-

fers great potential for the early detection of recur-

rent bladder carcinoma; their role in the evaluation of

haematuria is still uncertain

Prostate carcinoma

PSA

Benign prostatic hypertrophy

Infection e.g.

Urinary tract infection

Urine MCS

Prostatitis

Schistosomiasis

Terminal urine collected between 11h00 and 15h00

for microscopy

Tuberculosis Early morning urine specimen for AFB + mycobacte-

rial culture

Pyelonephritis

Urine MCS

Metabolic disorders e.g.

Hypercalciuria

Serum calcium

Hyperuricosuria

Serum uric acid

Vascular

Renal infarction

Trauma

Coagulation disturbance

Warfarin use

Coagulation studies

Heparin therapy

Thrombocytopenia

Strenous exercise Asymptomatic haematuria resulting from strenous ex-

ercise has been well documented in association with

a variety of contact and noncontacts sports. Exer-

cise-induced haematuria is typically a benign, self-

limiting process that resolves within 72 hours of onset.

If the haematuria is present on repeat urinalysis after

72 hours of rest, further urological evaluation may be

indicated.

REFERENCES

1. Sutton J M. Evaluation of hematuria in adults. J AMA 1990; 263: 2475 - 80

2. Abuelo GJ . The diagnosis of hematuria. Arch Intern Med 1983; 143: 967 - 70

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (890)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- Structuring Your Novel Workbook: Hands-On Help For Building Strong and Successful StoriesDocumento16 pagineStructuring Your Novel Workbook: Hands-On Help For Building Strong and Successful StoriesK.M. Weiland82% (11)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Komoiboros Inggoris-KadazandusunDocumento140 pagineKomoiboros Inggoris-KadazandusunJ Alex Gintang33% (6)

- Reducing Preventable Child MortalityDocumento172 pagineReducing Preventable Child MortalitySheral AidaNessuna valutazione finora

- Case History and Data Interpretation in Medical Practice, 3e (January 31, 2015) - (9351523756) - (Jaypee Brothers Medical Pub)Documento492 pagineCase History and Data Interpretation in Medical Practice, 3e (January 31, 2015) - (9351523756) - (Jaypee Brothers Medical Pub)Khan100% (3)

- Hamlet's Seven Soliloquies AnalyzedDocumento3 pagineHamlet's Seven Soliloquies Analyzedaamir.saeedNessuna valutazione finora

- Subway CalorieDocumento4 pagineSubway CalorieSheral AidaNessuna valutazione finora

- LMOD - BOOSTERChallenge - Game ChangerDocumento31 pagineLMOD - BOOSTERChallenge - Game ChangerSheral Aida100% (1)

- Clinical SkillsDocumento1 paginaClinical SkillsSheral AidaNessuna valutazione finora

- Examination 3rd Year StudentDocumento39 pagineExamination 3rd Year StudentSheral AidaNessuna valutazione finora

- AHA Diagnostic ECG Electrode PlacementDocumento2 pagineAHA Diagnostic ECG Electrode PlacementSheral AidaNessuna valutazione finora

- Guía para Diagnostico Con Oftalmoscopio y Otoscopio Welch AllynDocumento17 pagineGuía para Diagnostico Con Oftalmoscopio y Otoscopio Welch Allynguero3261Nessuna valutazione finora

- Aesthetic Plastic Surgery of The East Asian Face 2016 (UnitedVRG) PDFDocumento446 pagineAesthetic Plastic Surgery of The East Asian Face 2016 (UnitedVRG) PDFlee_tiffaNessuna valutazione finora

- 2015 Nissan GTRDocumento2 pagine2015 Nissan GTRSheral AidaNessuna valutazione finora

- How the Ophthalmoscope Detects Eye and Systemic DiseasesDocumento21 pagineHow the Ophthalmoscope Detects Eye and Systemic DiseasesSheral AidaNessuna valutazione finora

- TBL InfertilityDocumento3 pagineTBL InfertilitySheral AidaNessuna valutazione finora

- Otoscopy BasicsDocumento4 pagineOtoscopy BasicsSheral Aida100% (1)

- Healing With The Medicine of The ProphetDocumento652 pagineHealing With The Medicine of The Prophetahmed.ne7970Nessuna valutazione finora

- History 3rd Year StudentDocumento37 pagineHistory 3rd Year StudentSheral AidaNessuna valutazione finora

- TBL Infertility 2Documento6 pagineTBL Infertility 2Sheral AidaNessuna valutazione finora

- Facilitator ReportDocumento2 pagineFacilitator ReportSheral AidaNessuna valutazione finora

- Al5 & Al6 - Cranial Nerves: Origin POE No. Name Innervations Nucleus Component Distribution ForamenDocumento2 pagineAl5 & Al6 - Cranial Nerves: Origin POE No. Name Innervations Nucleus Component Distribution ForamenSheral AidaNessuna valutazione finora

- CNS DrugsDocumento8 pagineCNS DrugsSheral Aida100% (2)

- Introduction To Cardiovascular PhysiologyDocumento96 pagineIntroduction To Cardiovascular PhysiologyAmanda Karien MaraisNessuna valutazione finora

- CVS ElectrocardiogramDocumento167 pagineCVS ElectrocardiogramSheral AidaNessuna valutazione finora

- 02 CHET Handbook 2007 Contents FinalDocumento21 pagine02 CHET Handbook 2007 Contents FinalSheral AidaNessuna valutazione finora

- Treviranus ThesisDocumento292 pagineTreviranus ThesisClaudio BritoNessuna valutazione finora

- Price and Volume Effects of Devaluation of CurrencyDocumento3 paginePrice and Volume Effects of Devaluation of Currencymutale besaNessuna valutazione finora

- Term2 WS7 Revision2 PDFDocumento5 pagineTerm2 WS7 Revision2 PDFrekhaNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 8, Problem 7PDocumento2 pagineChapter 8, Problem 7Pmahdi najafzadehNessuna valutazione finora

- Haryana Renewable Energy Building Beats Heat with Courtyard DesignDocumento18 pagineHaryana Renewable Energy Building Beats Heat with Courtyard DesignAnime SketcherNessuna valutazione finora

- TOPIC - 1 - Intro To Tourism PDFDocumento16 pagineTOPIC - 1 - Intro To Tourism PDFdevvy anneNessuna valutazione finora

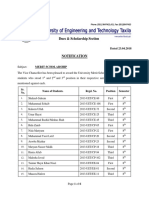

- Dues & Scholarship Section: NotificationDocumento6 pagineDues & Scholarship Section: NotificationMUNEEB WAHEEDNessuna valutazione finora

- Negotiating For SuccessDocumento11 pagineNegotiating For SuccessRoqaia AlwanNessuna valutazione finora

- Wells Fargo StatementDocumento4 pagineWells Fargo Statementandy0% (1)

- School of Architecture, Building and Design Foundation in Natural Build EnvironmentDocumento33 pagineSchool of Architecture, Building and Design Foundation in Natural Build Environmentapi-291031287Nessuna valutazione finora

- Criteria For RESEARCHDocumento8 pagineCriteria For RESEARCHRalph Anthony ApostolNessuna valutazione finora

- Spelling Errors Worksheet 4 - EditableDocumento2 pagineSpelling Errors Worksheet 4 - EditableSGillespieNessuna valutazione finora

- Senarai Syarikat Berdaftar MidesDocumento6 pagineSenarai Syarikat Berdaftar Midesmohd zulhazreen bin mohd nasirNessuna valutazione finora

- APPSC Assistant Forest Officer Walking Test NotificationDocumento1 paginaAPPSC Assistant Forest Officer Walking Test NotificationsekkharNessuna valutazione finora

- Prosen Sir PDFDocumento30 pagineProsen Sir PDFBlue Eye'sNessuna valutazione finora

- UNIT 1 Sociology - Lisening 2 Book Review of Blink by Malcolm GladwellDocumento9 pagineUNIT 1 Sociology - Lisening 2 Book Review of Blink by Malcolm GladwellNgọc ÁnhNessuna valutazione finora

- Global Supplier Quality Manual SummaryDocumento23 pagineGlobal Supplier Quality Manual SummarydywonNessuna valutazione finora

- Kepler's Law 600 Years Before KeplerDocumento7 pagineKepler's Law 600 Years Before KeplerJoe NahhasNessuna valutazione finora

- Intentional Replantation TechniquesDocumento8 pagineIntentional Replantation Techniquessoho1303Nessuna valutazione finora

- Pure TheoriesDocumento5 paginePure Theorieschristine angla100% (1)

- Sadhu or ShaitaanDocumento3 pagineSadhu or ShaitaanVipul RathodNessuna valutazione finora

- Algebra Extra Credit Worksheet - Rotations and TransformationsDocumento8 pagineAlgebra Extra Credit Worksheet - Rotations and TransformationsGambit KingNessuna valutazione finora

- 02 Activity 1 (4) (STRA)Documento2 pagine02 Activity 1 (4) (STRA)Kathy RamosNessuna valutazione finora

- Complete BPCL AR 2022 23 - English Final 9fc811Documento473 pagineComplete BPCL AR 2022 23 - English Final 9fc811Akanksha GoelNessuna valutazione finora

- Cover Letter IkhwanDocumento2 pagineCover Letter IkhwanIkhwan MazlanNessuna valutazione finora

- Robots Template 16x9Documento13 pagineRobots Template 16x9Danika Kaye GornesNessuna valutazione finora

- AR Financial StatementsDocumento281 pagineAR Financial StatementsISHA AGGARWALNessuna valutazione finora