Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Making Negotiated Land Reform Work: Initial Experience From Colombia, Brazil and South Africa

Caricato da

Sebastian Estrada JaramilloDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Making Negotiated Land Reform Work: Initial Experience From Colombia, Brazil and South Africa

Caricato da

Sebastian Estrada JaramilloCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Making Negotiated Land Reform Work: Initial

Experience from Colombia, Brazil and South Africa

KLAUS DEININGER *

The World Bank, Washington DC, USA

Summary. The paper describes background, initial experience, and future challenges

associated with a new ``negotiated'' approach to land reform. This approach has

emerged as, following the end of the Cold War and broad macroeconomic adjustment,

many countries face a ``second generation'' of reforms to address deep-rooted structural

problems and provide the basis for sustainable poverty reduction and economic growth.

It reviews possible theoretical linksthrough credit market or political channelsbe-

tween asset ownership and economic performance. Program characteristics in each

country, as well as lessons for implementation, and implications for monitoring and

impact assessment are discussed. 1999 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. INTRODUCTION

Theoretical reasons and empirical evidence

suggest that land reform may provide equity

and eciency benets. A large body of research

has demonstrated the existence of a robustly

negative relationship between farm size and

productivity due to the supervision cost asso-

ciated with employing hired labor. This implies

that redistribution of land from wage-operated

large farms to family-operated smaller ones can

increase productivity (Binswanger, Deininger

and Feder, 1995). In addition, access to assets

in general and land ownership in particular is

associated with improved access to credit

markets and can provide benets as an insur-

ance substitute to smooth consumption inter-

temporally. By enabling the poor to undertake

indivisible productive investments (or by pre-

venting them from irreversibly depleting their

asset-base) measures to improve the distribu-

tion of assets could lead to higher aggregate

growth, thus improving both equity and e-

ciency (see Bardhan, Bowles and Gintis,

forthcoming for references). Aggregate cross-

country regressions as well as more micro-level

evidence conrm the poverty-reducing and

growth-enhancing impact of a better distribu-

tion of productive assets.

This apparent potential notwithstanding,

actual experience with land reform has in many

instances fallen short of expectations. De-

spiteor becauseof this, land reform re-

mains a hotly debated issue in a number of

countries (e.g., Zimbabwe, Malawi, South Af-

rica, Guatemala, El Salvador, Brazil, Colom-

bia) some of which are spending considerable

amounts of resources for this purpose. A

mechanism to provide an eciency- and equity-

enhancing redistribution of assets that would

increase overall investment at a cost that is

comparable to other types of government in-

terventions would be very desirable.

This paper describes a new type of negotiated

land reform that relies on voluntary land

transfers based on negotiation between buyers

and sellers, where the government's role is re-

stricted to establishing the necessary frame-

work and making available a land purchase

World Development Vol. 27, No. 4, pp. 651672, 1999

1999 Elsevier Science Ltd

All rights reserved. Printed in Great Britain

0305-750X/99 $ see front matter

PII: S0305-750X(99)00023-6

*I would like to thank Hans Binswanger, Juliana

Bottia, Alain de Janvry, Gershon Feder, Gustavo

Gordillo de Anda, Adriana Herrera, John Heath, Nick

Krat, Marcos Lins, Michael Lipton, Anibal Llano,

Absalon Machado, Indran Naidoo, Pedro Olinto,

Manuel Rojas, Edson Teolo, Dina Umali-Deininger,

Hernando Urbina, Martien van Nieuwkoop, Stefan

Oehrlein, two anonymous reviewers, and seminar par-

ticipants in Helsinki, Santiago, Bogota, the University of

Sussex, and Washington, for valuable insights and

discussions. The opinions expressed in this paper are

those of the author and do not necessarily represent the

views of the World Bank, its Board of Directors, or the

countries they represent. Final revision accepted: 21

September 1998.

651

grant to eligible beneciaries. Section 2 dis-

cusses the land reform experience in general,

thus providing the historical background and

conceptual basis for the subsequent argument.

Section 3 is devoted to a more detailed de-

scription of negotiated land reform in Colom-

bia, covering the reasons for choosing a

negotiated approach, its principles, and its im-

plementation in a number of pilot municipios.

Section 4 compares the mechanisms utilized to

those adopted in Brazil and South Africa and

briey highlights some of the implications for

monitoring the new approach. Section 5 con-

cludes.

2. LAND REFORM: POTENTIAL AND

HISTORICAL EXPERIENCE

While land reform has long been the subject

of policy debate, the motivation for addressing

land issues has shifted considerably over time.

Initial discussions were largely motivated by

political considerations, supported by the no-

tion of the inverse farm-size productivity rela-

tionship. This notion had received empirical

support from cross-sectional studies across

states (Kutcher and Scandizzo, 1981), countries

(Berry and Cline, 1979), or individual farms

(Barraclough, 1970).

1

More recent contribu-

tions have emphasized the importance of asset

ownership in situations characterized by in-

complete contracting (Bardhan, Bowles and

Gintis, forthcoming; Ho and Lyon, 1994),

elaborating on models such as Dasgupta and

Ray (1986, 1987) and Moene (1992). The un-

derlying idea is that, in situations characterized

by credit rationing, individuals may not be able

to undertake indivisible investments in human

capital (schooling) or productive assets (wells,

bullocks, or perennials with a long gestation

period) that need to be nanced through credit.

This idea has been formalized in a number of

theoretical models where lack of collateral

keeps individuals in ``poverty traps,'' unable to

undertake highly protable indivisible invest-

ments (Galor and Zeira, 1993; Eckstein and

Zilcha, 1994).

2

In such a setting, the poor would fail to get

out of poverty, not because they are inherently

less productive or lack the necessary skills, but

because informational imperfections preclude

them from access to credit markets and be-

cause, as a consequence, they never get the

opportunity to utilize or develop fully their

abilities. If this is true, a one-o redistribution

to low-wealth groups could strictly dominate

other policy instruments (Ho and Lyon,

1994). In particular it will, in the medium to

long term, more eective and less costly than

continuing redistribution of income (e.g.,

through social programs) which would be as-

sociated with strong disincentive eects (Ba-

narjee and Newman, 1993; Mookherjee, 1997).

Support for the importance of asset (and in-

come) distribution for economic outcomes is

provided by cross-country regressions which

indicate the presence of a signicant negative

impact of the initial asset distribution on sub-

sequent economic growth (Birdsall and Lon-

don o, 1997). This growth-reducing impact is

particularly severe for the poor (Deininger and

Squire, 1998). Indeed, overall inequality seems

to have an important impact on societies'

ability to eectively and quickly respond to

exogenous shocks (Rodrik, 1998), the level of

crime (Fajnzylber, Lederman and Loayza,

1998), and the degree to which special interest

groups are able to appropriate rentswith

implications for overall productive eciency

(Banarjee et al., 1997).

Although inequality may signicantly aect

economic performance, historical examples for

major changes of inequality within a country

are rare (Li, Squire and Zou, 1998). More

specically, the success of land reform was

critically dependent on the form of production

into which it was introduced. In landlord estates

where tenants already cultivated the land and

all that was required was a reassignment of

property rights, land reform was relatively

straightforward and associated with signicant

productivity increases and the emergence of

stable systems of production.

3

The main reason

is that the organization of production remained

the same family farm system, and that bene-

ciaries already had the skills and implements

necessary to cultivate their elds. Organiza-

tional requirements of conducting such land

reforms were minimalmaking them compa-

rable to the ``stroke of a pen'' reforms familiar

from the literature on macroeconomic reform.

Indeed, since the end of WW II, landlord es-

tates in Bolivia, large areas of China, Eastern

India, Ethiopia, Iran, Japan, Korea, and Tai-

wan have been transferred to tenants in the

course of successful land reforms.

4

By contrast, land reform in haciendas, i.e.

systems where tenants had a small house-plot

for subsistence but worked the majority of the

time on the landlord's home farm, has been

very dicult, up to the point where the ``game

652 WORLD DEVELOPMENT

of Latin American Land Reform'' was declared

to be lost (De Janvry and Sadoulet, 1989). In

the large majority of cases large landowners

responded to the threat of land reform with

large-scale evictions long before governments

were able to eectively implement laws aimed

at tenant protection or land reform. They either

resumed extensive livestock production and

ranching oraided by signicant credit subsi-

diesstarted highly mechanized self-cultiva-

tion (Binswanger, Deininger and Feder, 1995).

This reduced tenant welfare, depopulated

farms, and created further diculties for re-

distributive land reform. The experience with

land reform in these environments points to-

ward three specic diculties:

First, the transfer from large to small farmers

requires a change in the pattern of production,

construction of complementary infrastructure,

subdivision of the farm, and settlement of ad-

ditional beneciaries over and above the

workers who have already been living on the

farm.

5

Farms acquired for purposes of land

reform have generally not been farmed at full

capacity, were run down or decapitalized, or

highly mechanized. In all of these cases failure

to bring in additional beneciaries, to provide

resources for simple works (cleaning of pas-

tures, fencing, construction of basic infra-

structure, etc.) during the startup phase, and to

ensure the availability of productive assets and

technical assistance to go with the land have

often contributed to the failure of reform ef-

forts.

6

Second, land reform beneciaries, even if

they are workers of the former farm, are rarely

accustomed to making independent entrepre-

neurial decisions, a constraint that is particu-

larly important if (as in many of the cases

described above) realization of the potential

benets from land reform requires signicant

modications in the farm's cropping pattern.

Programs that are limited to the mere transfer

of land, without training and technical assis-

tance, have made it dicult for beneciaries to

reach quickly an equilibrium characterized by

high levels of productivity and savings and, to

the degree that beneciaries were not able to get

access to these, may have resulted in a perma-

nent decrease in agricultural productivity.

Third, in rural environments with multiple

market imperfections, providing beneciaries

with access to land but not with access to

markets for output and credit may fail to make

them better o than before. This will be the case

particularly if landlords had provided their la-

bor tenants with inputs, credit, or market out-

lets before the reform.

7

Land markets therefore

have to be viewed in the context of the opera-

tion of other factor markets.

These generic land reform diculties were, in

past attempts to eect the redistribution of land

to the poor, often exacerbated by implementa-

tion-related issues. Instead of aiming to in-

crease productivity and reduce poverty, the

main goal of many land reforms in the past has

been to calm social unrest and allay political

pressures by peasant organizations.

8

Such re-

forms had often been initiated in response to

political pressure (or to divert attention from

other problems) rather than as part of a long-

term rural development strategy.

9

The resulting

reform measures were generally designed ad

hoc, bore little relation to actual needs on the

ground, and commitment to them faltered once

social emergencies had subsided. Furthermore,

attention often focused on the politically vocal

and well-connected peasants rather than rural

dwellers with the best ability to make produc-

tive use of the land, or the most deserving on

poverty grounds.

10

The costs of carrying out land reform were

often increased by the continued existence of

implicit and explicit distortions which drove

land prices above the capitalized value of ag-

ricultural prots and made it attractive for land

reform beneciaries to sell out to large farmers,

thus contributing to reconstruction on hold-

ings.

11

In addition, instead of aiming to create

conditions that would improve the functioning

of land rental and sales markets to complement

state-led reform eorts, governments have of-

ten completely outlawed or severely restricted

the operation of land rental (and to a lesser

degree sales) markets. This has eliminated an

important opportunity for landless individuals

to acquire farming experience, made the pro-

gress of land reform totally dependent on bu-

reaucratic eorts, and complicated the task of

targeting assistance to the poor. This complete

reliance on government spawned complex reg-

ulations and cumbersome bureaucratic re-

quirements to implement land reform, stretched

available administrative capacity (Lipton,

1974), and resulted in highly centralized pro-

cesses of implementation. Government bu-

reaucracies at the central leveljustied by the

need to provide technical assistance and other

support services to beneciariesproved ex-

pensive and, unable to utilize information from

the local level, often also quite ineective. (see

Table 1).

MAKING NEGOTIATED LAND REFORM WORK 653

T

a

b

l

e

1

.

C

o

m

p

a

r

i

s

o

n

o

f

m

e

c

h

a

n

i

s

m

s

t

o

i

m

p

l

e

m

e

n

t

m

a

r

k

e

t

a

s

s

i

s

t

e

d

l

a

n

d

r

e

f

o

r

m

i

n

C

o

l

o

m

b

i

a

,

B

r

a

z

i

l

,

a

n

d

S

o

u

t

h

A

f

r

i

c

a

C

o

l

o

m

b

i

a

B

r

a

z

i

l

S

o

u

t

h

A

f

r

i

c

a

I

N

C

O

R

A

N

e

g

o

t

i

a

t

e

d

I

N

C

R

A

N

e

g

o

t

i

a

t

e

d

P

i

l

o

t

s

L

a

n

d

s

e

l

e

c

t

i

o

n

S

e

l

e

c

t

i

o

n

b

y

I

N

C

O

R

A

d

e

f

a

c

t

o

r

b

a

s

e

d

o

n

p

o

l

i

t

i

c

a

l

p

r

e

s

s

u

r

e

;

C

o

s

t

o

f

$

1

8

0

0

0

2

2

0

0

0

p

e

r

f

a

m

i

l

y

.

B

y

b

e

n

e

c

i

a

r

i

e

s

;

w

i

t

h

m

e

a

n

s

t

o

i

n

c

r

e

a

s

e

t

r

a

n

s

-

p

a

r

e

n

c

y

a

n

d

p

r

o

v

i

d

e

t

e

c

h

n

i

c

a

l

a

s

s

i

s

t

a

n

c

e

.

P

u

r

c

h

a

s

e

o

r

e

x

p

r

o

p

r

i

a

t

i

o

n

;

a

v

e

r

a

g

e

c

o

s

t

o

f

$

1

1

6

0

0

p

e

r

f

a

m

i

l

y

;

m

a

i

n

l

y

l

e

g

a

l

i

z

a

t

i

o

n

o

f

o

c

c

u

p

i

e

d

l

a

n

d

s

.

N

e

g

o

t

i

a

t

e

d

b

y

c

o

m

m

u

n

i

t

y

;

w

i

l

l

i

n

g

s

e

l

l

e

r

(

i

n

c

l

u

d

i

n

g

b

a

n

k

s

)

-

w

i

l

l

i

n

g

b

u

y

e

r

;

e

x

p

e

c

t

e

d

c

o

s

t

$

3

0

0

0

p

e

r

b

e

n

e

c

i

a

r

y

.

C

o

m

m

u

n

i

t

y

i

n

i

t

i

a

t

i

v

e

.

L

a

n

d

n

a

n

c

i

n

g

7

0

%

o

f

l

a

n

d

v

a

l

u

e

(

u

p

t

o

$

2

2

0

0

0

)

a

s

g

r

a

n

t

(

2

0

%

c

a

s

h

;

5

0

%

b

o

n

d

s

)

;

3

0

%

t

h

r

o

u

g

h

C

a

j

a

A

g

r

a

r

i

a

c

r

e

d

i

t

(

l

e

n

g

t

h

y

d

e

l

a

y

s

)

.

C

o

m

m

e

r

c

i

a

l

b

a

n

k

a

d

-

m

i

n

i

s

t

e

r

s

g

r

a

n

t

r

e

s

o

u

r

c

e

s

a

n

d

p

r

o

v

i

d

e

s

a

d

d

i

t

i

o

n

a

l

c

r

e

d

i

t

f

o

r

l

a

n

d

p

u

r

c

h

a

s

e

a

n

d

w

o

r

k

i

n

g

c

a

p

i

t

a

l

.

T

D

A

s

f

o

r

u

n

i

m

p

r

o

v

e

d

l

a

n

d

a

n

d

c

a

s

h

f

o

r

i

m

p

r

o

v

e

m

e

n

t

s

a

n

d

c

r

o

p

s

;

b

e

n

e

c

i

a

r

i

e

s

i

n

t

h

e

o

r

y

e

x

p

e

c

t

e

d

t

o

p

a

y

b

a

c

k

;

n

o

t

e

n

-

f

o

r

c

e

d

.

L

o

a

n

t

o

a

p

p

r

o

v

e

d

b

e

n

e

c

i

a

r

i

e

s

f

r

o

m

a

c

o

m

m

e

r

c

i

a

l

b

a

n

k

(

c

o

n

-

s

i

d

e

r

a

b

l

e

s

u

b

s

i

d

y

e

l

e

m

e

n

t

)

.

M

a

x

.

g

r

a

n

t

o

f

R

1

5

0

0

0

f

o

r

l

a

n

d

p

u

r

c

h

a

s

e

;

s

e

p

a

r

a

t

e

p

l

a

n

n

i

n

g

g

r

a

n

t

.

B

e

n

e

c

i

a

r

y

s

e

-

l

e

c

t

i

o

n

P

o

i

n

t

s

c

h

e

m

e

f

o

r

s

o

c

i

a

l

n

e

e

d

a

n

d

a

g

r

i

c

u

l

t

u

r

a

l

e

x

-

p

e

r

i

e

n

c

e

;

i

n

p

r

a

c

t

i

c

e

a

d

-

h

o

c

s

e

l

e

c

t

i

o

n

b

a

s

e

d

o

n

i

n

d

i

v

i

d

u

a

l

f

a

r

m

s

.

C

o

m

p

r

e

h

e

n

s

i

v

e

r

e

g

i

s

t

r

a

-

t

i

o

n

;

a

n

d

p

r

e

-

s

e

l

e

c

t

i

o

n

b

a

s

e

d

o

n

s

o

c

i

a

l

c

r

i

t

e

r

i

a

.

F

i

n

a

l

s

e

l

e

c

t

i

o

n

b

a

s

e

d

o

n

p

r

o

d

u

c

t

i

v

e

p

r

o

j

e

c

t

s

.

T

h

r

o

u

g

h

I

N

C

R

A

b

a

s

e

d

o

n

e

x

a

m

i

n

a

t

i

o

n

o

f

a

g

r

i

c

.

k

n

o

w

l

e

d

g

e

;

i

n

p

r

a

c

t

i

c

e

a

l

m

o

s

t

a

l

l

a

r

e

r

e

g

u

-

l

a

r

i

z

e

d

s

q

u

a

t

t

e

r

s

.

S

e

l

f

-

s

e

l

e

c

t

i

o

n

o

f

b

e

n

e

c

i

a

r

i

e

s

;

c

l

e

a

r

a

n

c

e

o

f

p

r

i

c

e

a

n

d

t

i

t

l

e

b

y

S

t

a

t

e

L

a

n

d

I

n

s

t

i

t

u

t

e

;

d

e

c

e

n

t

r

a

l

-

i

z

e

d

a

p

p

r

o

v

a

l

.

O

c

c

u

p

i

e

d

l

a

n

d

s

i

n

e

l

i

g

i

b

l

e

.

S

e

l

f

-

s

e

l

e

c

t

i

o

n

o

f

b

e

n

e

c

i

a

-

r

i

e

s

s

u

b

j

e

c

t

t

o

m

a

x

i

m

u

m

i

n

c

o

m

e

c

r

i

t

e

r

i

o

n

(

<

R

1

5

0

0

p

e

r

m

o

n

t

h

)

.

F

a

r

m

i

n

g

p

r

o

j

e

c

t

d

e

n

i

t

i

o

n

P

e

r

c

e

i

v

e

d

t

o

b

e

n

e

c

e

s

-

s

a

r

y

o

n

l

y

t

o

o

b

t

a

i

n

i

n

g

a

b

a

n

k

l

o

a

n

.

K

e

y

i

s

s

u

e

f

o

r

s

e

l

e

c

t

i

o

n

;

d

i

e

r

e

n

t

f

o

r

m

s

o

f

t

e

c

h

n

i

-

c

a

l

a

s

s

i

s

t

a

n

c

e

a

v

a

i

l

a

b

l

e

.

F

a

r

m

m

o

d

e

l

s

a

v

a

i

l

a

b

l

e

a

t

m

u

n

i

c

i

p

a

l

l

e

v

e

l

.

N

o

s

p

e

c

i

c

a

r

r

a

n

g

e

m

e

n

t

s

.

U

p

t

o

8

%

o

f

p

r

o

j

e

c

t

v

a

l

u

e

a

v

a

i

l

a

b

l

e

f

o

r

t

e

c

h

n

i

c

a

l

a

s

s

i

s

-

t

a

n

c

e

i

n

p

r

o

j

e

c

t

p

r

e

p

a

r

a

t

i

o

n

a

n

d

i

m

p

l

e

m

e

n

t

a

t

i

o

n

.

F

a

r

m

m

o

d

e

l

s

e

l

a

b

o

r

a

t

e

d

a

t

s

t

a

t

e

l

e

v

e

l

.

P

r

o

v

i

n

c

i

a

l

p

l

a

n

i

s

a

p

r

e

-

c

o

n

d

i

t

i

o

n

b

u

t

f

e

w

s

p

e

c

i

c

g

u

i

d

e

l

i

n

e

s

p

r

o

v

i

d

e

d

a

n

d

n

o

f

a

r

m

m

o

d

e

l

s

a

r

e

e

l

a

b

o

r

a

t

e

d

.

O

t

h

e

r

n

a

n

c

i

n

g

C

r

e

d

i

t

f

o

r

l

a

n

d

a

n

d

w

o

r

k

i

n

g

c

a

p

i

t

a

l

i

s

t

h

e

b

i

g

b

o

t

t

l

e

n

e

c

k

c

a

u

s

i

n

g

i

m

p

l

e

m

e

n

t

a

t

i

o

n

d

e

l

a

y

s

.

I

n

d

e

p

e

n

d

e

n

t

n

a

n

c

i

a

l

i

n

-

s

t

i

t

u

t

i

o

n

s

t

o

p

r

o

v

i

d

e

i

n

-

t

e

g

r

a

t

e

d

c

r

e

d

i

t

f

o

r

t

h

e

w

h

o

l

e

p

r

o

j

e

c

t

.

C

r

e

d

i

t

o

f

u

p

t

o

$

1

1

5

0

(

a

v

e

r

a

g

e

$

6

1

0

)

f

o

r

f

o

o

d

a

n

d

h

o

u

s

i

n

g

a

n

d

$

7

5

0

0

(

a

v

e

r

a

g

e

$

4

5

0

0

)

f

o

r

w

o

r

k

i

n

g

c

a

p

i

t

a

l

.

7

0

%

s

u

b

s

i

d

y

e

l

e

m

e

n

t

;

m

i

n

i

m

a

l

c

o

s

t

r

e

c

o

v

e

r

y

.

A

c

c

e

s

s

t

o

P

R

O

C

E

R

A

c

r

e

d

i

t

l

i

k

e

o

t

h

e

r

l

a

n

d

r

e

f

o

r

m

b

e

n

e

-

c

i

a

r

i

e

s

.

R

e

s

p

o

n

s

i

b

i

l

i

t

y

o

f

b

e

n

e

c

i

a

-

r

i

e

s

.

O

-

f

a

r

m

i

n

v

e

s

t

-

m

e

n

t

s

C

o

m

p

l

e

x

s

e

t

o

f

i

n

t

e

r

i

n

-

s

t

i

t

u

t

i

o

n

a

l

c

o

o

r

d

i

n

a

t

i

o

n

w

i

t

h

l

i

t

t

l

e

r

e

s

u

l

t

s

u

p

t

o

n

o

w

.

I

d

e

n

t

i

e

d

a

n

d

c

o

s

t

e

d

i

n

m

u

n

i

c

i

p

a

l

l

a

n

d

r

e

f

o

r

m

p

l

a

n

.

P

r

o

v

i

d

e

d

b

y

I

N

C

R

A

(

$

3

2

0

0

i

n

1

9

9

4

,

n

o

w

u

p

t

o

$

8

0

0

0

)

;

a

l

m

o

s

t

a

l

l

f

o

r

r

o

a

d

s

.

G

r

a

n

t

o

f

$

4

0

0

0

p

e

r

b

e

n

e

-

c

i

a

r

y

;

d

i

s

b

u

r

s

e

d

d

i

r

e

c

t

l

y

t

o

c

o

m

m

u

n

i

t

y

.

S

e

r

v

i

c

e

s

a

n

d

t

o

s

o

m

e

e

x

t

e

n

t

i

n

f

r

a

s

t

r

u

c

t

u

r

e

a

r

e

p

r

o

v

i

n

-

c

i

a

l

r

e

s

p

o

n

s

i

b

i

l

i

t

y

;

c

o

o

r

d

i

-

n

a

t

i

o

n

w

i

t

h

t

h

e

c

e

n

t

e

r

i

s

s

t

i

l

l

w

e

a

k

.

654 WORLD DEVELOPMENT

3. NEGOTIATED LAND REFORM IN

COLOMBIA

(a) Background

(i) Land reform before 1994

In Colombia, land reform has been a long-

standing concern to correct an extremely ineq-

uitable distribution of land, to increase the

productivity and environmental sustainability

of agricultural production, and to reduce

widespread rural violence. Maldistribution of

land in rural areas, while dating back to the

encomiendas given out following the Spanish

conquest, has been reinforced and exacerbated

in more recent times by a number of policy

related factors.

12

These include:

Tax incentives for agriculture that implied

that rich individuals acquired land in order to

oset taxes on nonagricultural enterprises.

Legal impediments to the smooth func-

tioning of the land rental and sales markets.

Share tenancy was either directly outlawed

or, when this was lifted, discouraged by the

fact that tenants would receive property

rights to whatever land improvements they

had made, making it in principle impossible

to terminate their leases.

Credit and interest rate subsidies plus dis-

proportionate protection of the livestock sub-

sector provided incentives for agricultural

cultivation with very low labor intensity

(World Bank, 1996).

The use of land to launder money that had

been acquired by drug lords.

These factors have profound implications for

factor use, employment generation, and welfare

in rural areas. First, while small farmers were

often driven o their traditional lands to eke

out a living in marginal and environmentally

fragile areas, much of the best agricultural land

(75% of the land suitable for crop production)

was devoted to extensive livestock grazing or

not farmed at all due to violence (Heath and

Binswanger, 1996). This suggests that there are

indeed large tracts of unutilized or underuti-

lized land which could be subjected to land

reform in order to increase agricultural pro-

ductivitya notion in line with available em-

pirical evidence.

13

Second, economic growth has been labor-

saving. Since the 1950s, the rate of growth of

rural employment has been signicantly lower

than aggregate economic growth, which is

surprising even by the standard of other Latin

American countries (Mision Social, 1990). This

appears to have increased peasants' inclination

to support, or at least live with exceptionally

high levels of rural violence that increasingly

constitute a drag on the whole economy (esti-

mates in the Colombian press put the losses

associated with rural violence at about 15% of

GDP). The government sees the reduction of

rural violence as an important goal of land re-

form.

Third, structural adjustment made the lack of

adaptability in the large farm sector particularly

blatant. Elimination of credit subsidies caught

large mechanized farms that cultivated mainly

traditional crops with minimal labor inputs in a

debt-trap that made them unable to adjust to

the new environment and take advantage of the

opportunities for exports of nontraditional and

more labor-intensive crops. Unable to respond

to the loss of agricultural protection in a pro-

ductive way, the large farm sector resorted to

large-scale lobbying. Establishment of a dy-

namic small farm sector would, it was hoped,

enable Colombia to capitalize on its agro-eco-

logical diversity and signicantly increase its

exports of traditional and nontraditional crops.

None of these concerns are new. The mal-

distribution of productive resources, especially

land, was identied as one of the root causes of

economic stagnation by a World Bank mission

in the 1950s. In 1961, the government estab-

lished the National Land Reform Institute

(Instituto Nacional Colombiano de Reforma

Agraria or INCORA), to bring about a more

equitable distribution of assets in the rural

economy. But even though considerable

amounts of resources were spent on land re-

form (INCORA's average annual budget in the

late 1980s was about US $140 million), most

was spent on a large bureaucracy

14

and almost

35 years of operations had produced little vis-

ible eect on the ground. INCORA appeared to

be more eective in regularizing spontaneous

settlement on the frontier than in converting

the landless into successful agricultural entre-

preneurs in areas that were previously culti-

vated by large owners. Even where land reform

did distribute land, lack of capital forced many

beneciaries to abandon full-time agriculture

and rent out part or all of their land, often to

the old landlord. In the aggregate, between the

1960s and 1990, the Gini coecient of the op-

erational land distribution fell by only three

percentage points, from 0.87 to 0.84.

MAKING NEGOTIATED LAND REFORM WORK 655

(ii) The new Law and its implementation

Not unrelated to the loss of INCORA's tra-

ditional source of nancea share of duties on

agricultural imports that was eliminated with

agricultural trade liberalizationa law was

passed in 1994 that would allow for a more

decentralized and demand-driven process. De-

spite favorable preconditions, however, and the

government's expressed determination to dis-

tribute one million hectares within four years,

the land reform program had a disappointingly

slow start.

15

Before describing the new imple-

mentation arrangements that emerged to im-

prove on this, it is worthwhile to consider the

main reasons for this lackluster performance

and the measures taken to address this issue.

To overcome the ``fundamental nancing

problem of the poor'' (Binswanger and Elgin,

1988;Carter and Mesbah, 1993), i.e. the fact

that fully mortgage-based nancing of land

purchases by the poor is infeasible, the Co-

lombian Land Reform Law provides for a land

purchase grant. The grants amounts to 70% of

the negotiated land purchase price, up to a

maximum that was based on historical land

reform allocations.

16

The grant, however, was

restricted to the purchases of land and could

not be used to undertake complementary in-

vestments. This created incentives for collusion

between sellers and buyers to overstate land

prices, divide the surplus between them, and let

the government foot the bill.

17

The resulting

incentive structure was strongly biased in favor

of the transfer of developed agricultural land

close to infrastructure and already well en-

dowed with the necessary complementary in-

vestment. This tended to reduce land reform to

a mere redistribution of existing assets rather

than the creation of new ones, by targeting

underutilized lands and helping beneciaries to

undertake signicant investments. To deal with

these issues, it was claried that the goal of

market assisted land reform is the establish-

ment of viable productive projects (proyectos

productivos), rather than the mere transfer of

land. A mechanism was devised to facilitate use

of grant funds to nance nonland investments,

thus overcoming the bias inherent in previous

legal provisions.

18

A second issue was that, to create viable ag-

ricultural enterprises, rather than a ``rural

proletariat,'' a target income from full-time

agriculture (equivalent to a minimum farm size

of about 15 hectares) was legally required. This

neglected the potential of the poorespecially

those in proximity to urban areasto derive

income from a variety of sources and together

with a prohibition of rental and sale, left little

room either for the exit of unsuccessful bene-

ciaries or the gradual expansion of the hold-

ings of successful ones through rental or

purchase of additional land. It also demon-

strated little awareness of the requirements, in

terms of human capital, other assets, and ex-

perience with nancial and marketing institu-

tions, associated with operating a 15-hectare

farm.

19

As a result, the law was in danger of

concentrating large amounts of subsidies on a

well-connected ``agrarian bourgeoisie'' while

leaving the majority of potential beneciaries

uncovered.

20

To overcome this shortcoming,

the target income was reduced by one-third

and, rather than being based on general aver-

ages, is to be assessed based on a project-spe-

cic plan elaborated by beneciaries that

included income from nonagricultural sources.

Finally, even though the law provides for an

exemplary and elaborate institutional struc-

ture

21

to facilitate an encompassing process of

reform, the fact that there was little incentive

for local leaders to actually establish the nec-

essary structures implied that it was dicult to

make the model operational and ensure eec-

tive beneciary participation. Lack of dissemi-

nation of the law prevented a truly democratic

process at the local level. Continued subsidi-

zation of INCORA drove out private service

providers

22

and ``success'' continued to be de-

ned in terms of transferring land and ex-

hausting budgets rather than in establishing

viable rural enterprises. To change this, a shift

of responsibility for approval from INCORA's

headquarters to regional oces was accompa-

nied by transferring resources directly to local

communities and by clarifying that, among

others, existence and functioning of a munici-

pal council was a precondition for municipios

to become eligible for land reform funds.

(b) Implementation

While the rst two years of program imple-

mentation highlighted critical shortcomings,

they provided little insight in how to actually

implement such a program. In this section we

use the experience from ve pilot municipios,

selected to reect the heterogeneity of the

country,

23

to illustrate four key elements for

implementation namely

656 WORLD DEVELOPMENT

making land reform a program ``owned''

by the local government, thus achieving bet-

ter integration of land reform with existing

municipal development priorities or invest-

ments and at the same time greatly reducing

transaction costs

requiring the elaboration of productive

projects that provide the basis for a more

programmatic approach to beneciary train-

ing, negotiation of land prices, and an eco-

nomic evaluation of the expected benets

and costs of land reform

establishing a decentralized and ``hands

on'' program of beneciary training that

would act as a means of pre-selecting bene-

ciaries (based on their willingness to partici-

pate), help them to overcome their structural

diculties, ensure greater ``ownership'' and

ultimately economic sustainability of projects

insisting on a transparent and public pro-

cess of project approval and linking the need-

ed mechanisms of accountability directly to a

process of monitoring and evaluation that

links to the municipal land reform plan, aims

to detect quickly deviations from targets and

the reasons for them, and forms the basis for

an in-depth impact assessment of the land re-

form process at a later stage.

The expectation is that the steps taken by local

governments to improve infrastructure and

functioning of other factor markets, together

with land-reform specic measures (described

in detail below), would improve potential ben-

eciaries' capacity to negotiate and make pro-

ductive use of land and at the same time reduce

the gap between the net present value of agri-

cultural prots land prices. This, in turn, would

reduce the size of the land purchase grant re-

quired per person, thus making it possible to

use a given amount of grant money to attend to

a larger number of beneciaries.

(i) The municipal land reform plan

A key document in the pilot municipios has

been a municipal land reform plan. This plan,

elaborated in a decentralized fashion, contains

information about demand and supply of land

for land reform purposes, and a characteriza-

tion of the institutional environment and re-

sponsibilities for land reform. Following a

systematic procedure to establish a municipal

plan is expected to have three main benets.

The rst is to identify potential demand for

this type of land reform. This includes steps

such as raising awareness among the bene-

ciary population and help target the most nee-

dy, to establish a transparent process that can

ground land reform rmly within the context of

other local development initiatives, to identify

the potential demand for land reform, and to

develop realistic expectations about the extent

to which land reform can contribute to the

solution of existing problems.

A second benet is to identify potential supply

and to generate the basis for reasonably com-

petitive land markets by ensuring that supply of

land (at reasonable prices and in areas suitable

for small farmer cultivation) exceeds demand.

A nal issue is the establishmentat the lo-

cal levelof the institutional infrastructure

needed for eective implementation of land

reform. To ensure sustainability of land reform

projects, it has proven to be critical to identify

nongovernment organizations (NGOs) who are

able to provide continuing technical assistance,

and nancial institutions who are in a position

to extend and eectively supervise credit to land

reform beneciaries. These elements, together

with information on the contributions expected

from dierent participants (beneciaries, cen-

tral government, local institutions), makes it

much easier for local authorities to elaborate a

coordinated program of land reform that is in

line with the specic needs and opportunities,

including the scal capacity, of the municipio.

(ii) Identication of potential beneciaries

Under the process followed before initiation

of the pilots, selection of beneciaries was often

arbitrary and ad hoc. Despite the regulations of

the new law, INCORA continued to select

beneciaries on a case by case basis once a

given farm had been put up for sale and central

approval for the release of the necessary land

purchase funds had been obtained. In these

cases, to be able to disburse funds quickly, sales

of farms were often quite secretive, despite the

existence (on paper) of a needs-based quali-

cation system. The selection committees that

were established included workers of the exist-

ing farm who were generally careful not to

admit too many contenders from outside.

24

To ensure participation beyond the mem-

bership of well-established campesino organi-

zations and a transparent and more competitive

market for land, this approach has, in the pilot

municipios, been replaced by a procedure

that aims to create the basis for land transac-

tions through a more competitive market. To

MAKING NEGOTIATED LAND REFORM WORK 657

identify potential demand, a systematic infor-

mation campaign to disseminate the law, with

subsequent inscription of potential land reform

beneciaries (aspirantes) in a registry to be

maintained by INCORA, is conducted

throughout the municipio. A questionnaire

provides basic information on beneciaries'

educational level, their agricultural experience

(if any), their income sources, and their access

to other types of government services such as

education or health. Based on this, a pre-

qualication, essentially a means test based on

assets, is conducted.

Experience indicates that enabling potential

beneciaries to register at public oces and

police stations in outlying villages has consid-

erably broadened the outreach of the program.

Contrary to the procedures followed earlier by

INCORA, the information supplied is checked

for consistency, resulting in the elimination of a

large number of non-qualied applications. The

names of rejected and accepted aspirantes (with

reasons for rejection) are posted publicly. The

publicity of the selection process seems to have

increased accountability, and facilitated a better

understanding of the scope and limitations of

land reform by local authorities and potential

beneciaries. In all of the pilot municipios, al-

ternative programs have been initiated to

(temporarily or permanently) take care of the

specic needs of groups who will not be able to

benet from land reform in the immediate fu-

ture. These programs include chicken hatcheries

and other microenterprises for female house-

hold heads, construction of rural roads under

seasonal food for work schemes, as well as re-

forestation of environmentally fragile zones.

In addition to generating awareness for the

program, its potential target group, and the

characteristics of demand, the process of ben-

eciary selection also provides a basis for local

authorities to integrate land reform into a

broader program of capacity building and so-

cial assistance at the municipal level. This could

contribute to the resolution of at least some

aspects of the potential conict between the

dual objectives of equity and eciency which is

to some extent unavoidable if land reform is to

make a long-term sustainable contribution to

poverty reduction.

(iii) Creating the basis for a functioning land

market

The availability of large amounts of unuti-

lized or underutilized land in large holdings

implies that, in a reasonably uid land market

there would be plenty of supply to enable po-

tential beneciaries to choose the most suitable

lands and negotiate to obtain a competitive

price. In practice, however, land markets have

found to be thin, highly segmented, character-

ized by high transaction costs, and often pu-

shed into informality (FAO, 1994). Credit

market imperfections, lack of market informa-

tion by potential sellers, and the non-existence

of farm models suited to the specic needs and

factor endowments of small agricultural pro-

ducers, have prevented such an outcome and

contributed to the fact that beneciaries under

the old-style reform program often acquired

marginal lands at highly exaggerated prices

without being able to make productive use of

it.

25

In the pilot municipios, a procedure similar to

the identication of demand for land is also

being followed on the supply side. The rst step

is to determine ecologically suitable zones and,

based on cadastral information, establish an

inventory of the land according to size classi-

cation that could be used to identify target

areas for agrarian reform. Areas where land

reform would result in environmental hazards,

where soil fertility is insucient, or where the

existing ownership structure is already charac-

terized by small to medium-sized holdings, are

thus eliminated a priori. This gives beneciaries

a better idea of where to focus their eorts,

helps to set realistic goals, and puts into per-

spective the potential contribution of land re-

form for solving the social problems of a given

municipio. It increases not only awareness of

the scope for land reform as compared to other

options aiming at overall development of the

municipio (and the degree to which the success

of land reform will depend on such comple-

mentary measures), but also forces local gov-

ernments to think about potential levers (from

land taxes to land price information systems

and training to increase the productive capacity

of potential beneciaries) that they can utilize

to achieve an process of ``integrated land mar-

ket development''.

26

Experience from the pilots

indicates that land that had traditionally been

oered to INCORA for land reform was often

of marginal quality and hardly suitable for land

reform while some of the best land continued to

lie idle or underutilized. Specic measures to

resolve this issue have included:

Increasing sellers' awareness of the scope

and potential for alternative forms, such as

658 WORLD DEVELOPMENT

land rental that could temporarily or perma-

nently provide potential beneciaries with ac-

cess to land increases eciency and may serve

as a springboard for the landless to acquire

the information and agricultural experience

necessary to put together a productive pro-

ject.

Encouraging more eective collection of

existing municipal land taxesa strategy in

line with the central government's desire to

increase the revenue base of local govern-

ments and to gradually reduce the need for

central transfers.

More eective and systematic dissemina-

tion of information not only among potential

buyers but also any sellers of land, specically

information on the mechanisms of market-as-

sisted land reform and the modalities of pay-

ment under this program.

There is justied concern that a program that

provides targeted support to land purchases

may contribute to an increase in land prices,

and therefore benet former landowners rather

than the poor farmers who receive the land. To

deal with this, it has been decided that, to be

eligible for land reform benets, municipios

need to provide evidence (using actual sale in-

scriptions/oers by landowners) that existing

land supply is at least three times the amount of

land to be transacted under the land reform

program.

(iv) Establishing the Institutional basis

Experience suggests that, in the absence of

technical support during the startup phase and

without access to markets for nance and out-

puts, the sustainability of newly initiated land

reform settlements will be limited. The munic-

ipal plan thus contains a list of qualied pro-

viders of technical assistance from which

potential beneciaries can choose one to use the

part of the land purchase grant that is ear-

marked for technical assistance. In addition, it

aims to identify nancial institutions that

would be willing to lend to land reform bene-

ciaries. The rationale for this is simple: It is

likely to be futile to initiate a large process of

land reform in a municipio where neither credit

nor product markets are accessible to potential

beneciaries or where capacity to provide

technical assistance is grossly inadequate.

While identifying nancial intermediaries who

would in principle be willing to lend to land

reform beneciaries does not imply that every

application will automatically be approved, it

can help both parties to be more clear about the

rules of the game from the beginning and, in

addition, signicantly reduce the search cost to

be incurred by individual beneciaries.

(v) Formulation of productive projects

To help beneciaries assess the requirements,

opportunities, and risks they will face as inde-

pendent farmers more realistically, elaboration

of model farm projects has proved to be criti-

cal. While these models are necessarily abstract

and therefore not directly applicable to the

circumstances of specic beneciaries or farms,

they enable beneciaries and technical assis-

tance providers to be more specic about key

factors such as marketing channels, input sup-

plies, working capital requirements, etc. that

need to be made more concrete during the

subsequent process.

Under the approach followed by INCORA,

where agricultural productivity received little if

any consideration, beneciaries generally elab-

orated their ``productive projects'' after getting

access to the land, with little systematic guid-

ance and no discretion in the use of the tech-

nical assistance funds which were administered

by INCORA (often with ``beneciaries'' re-

ceiving no benets at all). Without a clear un-

derstanding of the economic potential of the

farms to be established, expected returns, and

alternative options (within or outside the land

reform program), beneciaries' ability to en-

gage in substantive bargaining was greatly di-

minished. It was only natural that INCORA

took the lead in ``negotiating'' with the land-

lord; a type of negotiation which ordinarily

amounted to mere formality and generally re-

sulted in acceptance of the price set by an

``independent'' assessor who was contracted by

the landlord and paid in proportion to the as-

sessed farm value.

The pilot experience has indicated that, un-

less beneciaries have a clear idea of productive

opportunities consistent with their abilities be-

fore they formulate productive projects that

form the basis for ``shopping'' for land, it is

very dicult to break this deadlock. To this

end, agricultural professionals that are con-

tracted through beneciary representatives help

establish crop budgets for a range of options

actually practiced in the municipio and conduct

training courses and meetings to disseminate

them. Aggregation of these into farm plans in-

volving more intensive land use and sustainable

MAKING NEGOTIATED LAND REFORM WORK 659

income to beneciaries provides the basis for

the formulation of ``productive projects'' by

individual beneciaries. Only after potential

beneciaries have understood the model bud-

gets, including their requirements and eco-

nomic implications, do they proceed to a pre-

selection of farms they might like to visit.

Thus, instead of being regarded as a tedious

necessity to obtaining access to complementary

credit (as under the old program), farm plans

under the pilot program acquired signicant

importance in a number of aspects. First, from

a substantive point of view the farm models

that have been established thus far do consti-

tute a break with the past in that the main goal

is to provide full employment of the family's

labor force throughout the year. Second, farm

plans are characterized by a focus on high value

crops rather than traditional bulk commodities,

greater diversication of crop production, and

an important livestock component. Third, all

plans include a signicant ``garden plot,'' set-

ting aside about one hectare for domestic con-

sumption needs (including chickens, one pig,

and a cow) and intensive cultivation of vege-

tables or fruits, the surplus of which is to be

sold in the market. In the process of shifting

emphasis towards these goals, the importance

of land area has declined signicantlyin

many cases the land area is between 30% and

50% of what had been the standard under

earlier land reform programs. In addition to

this, farm plans also serve as a rst step toward

the identication and prioritization of invest-

ment needs, and to provide a justication for

guiding the allocation of public funds to the

most productive use.

(vi) Beneciary training and project approval

Negotiated land reform requires beneciaries

to take considerable initiative and perform

tasks such as group formation, selection of a

viable farm model, adaptation of this general

model to the conditions of a specic farm,

identication of the productive value of at least

a number of farms available for sale, negotia-

tion of a purchase price with the farm owner,

arrangement for a credit to nance the land and

capital requirements that are not covered by the

purchase grant, formulation of a strategy to

establish needed on-farm infrastructure, and

eventually cope with the challenges and risks

associated with sustaining an economically vi-

able farm enterprise. Given their limited en-

dowments and experience, potential

beneciaries are generally unable to go through

the steps required in a ``negotiated'' type of

land reform without assistance. In fact, while

most of the beneciaries pre-selected in the pi-

lot had some kind of agricultural experience,

almost one quarter was illiterate and 70% had

ve years or less of formal education. While

many were in a great rush to receive land, their

ability to negotiate or manage resources was

clearly limited. Furthermore, even though

many beneciaries came in pre-existing groups,

these groups were often based on coincidence

more than on similarity of interest. Their ca-

pacity to resolve internal conicts or to devise

eective strategies to achieve common goals

was low or non-existent. Problems that will

inevitably arise in jointly establishing and sus-

taining an agricultural enterprise would prob-

ably have led to the paralysis or breakup of

many of these groups.

27

To remedy this, and thus increase the scope

for land reform to lead to productivity-en-

hancing outcomes, an in-depth training pro-

gram for pre-selected aspirantes was

developed.

28

This program, which is nanced

from INCORA's administrative budget, aims

to cover not only abstract principles but to

enable beneciaries to formulate a viable farm

plan. The ``theory'' part includes topics that

range from group dynamics and negotiation to

economic analysis, farm management, and

budgeting. Simultaneously, or as soon as ben-

eciaries have tentatively formed groups and

decided for certain crop combinations, this is

translated into practice in the context of visits

to farms that have been oered for sale, cal-

culation of the potential of these farms to

generate revenue, the implications for the price

that can be paid, the needed startup invest-

ments to allow productive use of the farm, and

the way in which these can be eected in

practice by the beneciary group.

Contrary to widespread fears, lack of local

capacity has not been a problem in developing

these training programs. Local universities,

NGOs, farmers' organizations, and govern-

ment institutions (including INCORA) are en-

thusiastic to utilize synergies in providing such

support in the expectation that they will follow

the projects at least through the establishment

phase. While the costs of this component are

not negligible (about US $1,800 per benecia-

ry), this is not only less than one-third of what

was spent by INCORA under the old process

but can be more than justied in terms of the

outcomes achieved in negotiations. Prices paid

660 WORLD DEVELOPMENT

for comparable farms under the pilot were

about 40% lower than what had been paid in

the previous year under INCORA's program.

29

Furthermore, while under the INCORA pro-

cess some beneciaries cancelled technical as-

sistance contracts that had existed under the

previous owner, pilot beneciaries are keenly

aware of the importance of continuing techni-

cal support and provisions to pay for this ser-

vice out of farm revenues are made in all of the

respective farm budgets.

A review of unsuccessful land reform cases

had indicated two main reasons for failure. One

was the absence of a fully funded plan to un-

dertake the investments needed to convert the

large farm into an enterprise suitable for small

farmer cultivation, and the lack of funds to

carry beneciaries through to the rst harvest.

To deal with this, the training phase is utilized

to develop, together with beneciaries, a de-

tailed plan (with monitoring indicators) for the

non-farm investments needed to convert the

farm into a smallholder enterprise. The ability

to obtain partial funding for the startup activ-

ities undertaken during this phase has proven

to be critical for the project's success.

The second problem was related to lack of

access to credit and output markets. Under the

pilot, agreements have been reached with a

number of cooperative banks already active in

rural areas to lend to land reform beneciaries

and thus compete with the government-owned

bank that has traditionally provided nancing

to land reform beneciaries. The preferred ar-

rangement bears similarity to contract farming

whereby the bank works closely with the pro-

viders of technical assistance (ensuring that the

farm business established by beneciaries

would indeed generate the desired revenues)

and help farmers market produce. This enables

them to supervise the use of the credit more

closely, to ensure that enterprises are indeed

developing their productive potential, and to

deduct loan repayments at the source, rather

than relying on unrealistic expectations of

foreclosure. Problems of interinstitutional co-

ordination (essentially the inability of the in-

stitutions who have traditionally administered

these funds to work with nongovernmental in-

stitutions) have prevented broader extension of

this model. But, beneciaries from all the pilot

municipios are unequivocal in their preference

for dealing with a predictable private sector

institution rather than with an unpredictable

bureaucracy that is directly or indirectly de-

pendent on government.

30

In line with the principle that responsibility

has to rest at the local level, all of the pilot

municipios decide about the approval (and

funding) of specic productive projects in

public sessions of the municipal councilgen-

erally with record attendance. In these sessions

beneciaries have to present and defend their

project, thus not only indicating that they un-

derstood the critical issues, but also providing

an example to guide other candidates for the

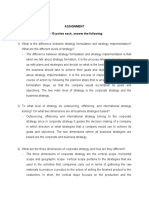

Table 2. Key variables for land reform planning, monitoring, and impact assessment

Municipal land reform plan Monitoring Impact assessment

Beneciaries Beneciary identication Grant per beneciary/employment. Increase in income

Beneciary prole

(capacity; welfare)

Group formation. Additional

employment generated.

Consumption smoothing

(assets).

Training requirements Targeting eciency.

Improvements in access to land.

Credit market access

Social services.

Reduction of violence

Projects Demand and supply of land Characteristics of farms transferred. Agricultural productivity

Char's of productive projects Implementation of projects. Environmental sustaina-

bility

Complementary investments

needed

Repayment performance

(planned and actual).

Reconcentration of land?

Cost by component Targeting of underutilized lands

Institutions Institutional capacity: Local and

central government (tech. assist.

legal framework private sector

(banks, input suppliers, marketing)

NGOs (training, evaluation))

Eectiveness in dissemination and

capacity building

Strengthened local

government.

Eciency of land transfer process. Fiscal sustainability

Private sector/NGO participation. Degree of decentraliza-

tion

MAKING NEGOTIATED LAND REFORM WORK 661

land purchase grant and thus setting the stage

for a transformation of the image of land re-

form in more general terms. In addition to

generating positive feedback loopsbenecia-

ries who were selected in last year's INCORA

land reform projects have already demanded

access to similar technical assistancethis also

establishes the basis for community-based

monitoring and social control to ensure that

beneciaries' performance does actually live up

to expectations.

(vii) Monitoring and evaluation

It is well known that decentralization without

adequate mechanisms of accountability may

not have the desired consequences. In addition

to helping focus on project quality rather than

merely physical quantities (e.g., land trans-

ferred) as an outcome indicator, a system that

monitors successive stages of land reform im-

plementation would help to quickly identify

and rectify unforeseen deviations from the

program's overall objectives, in addition to

assessing its long-term impacts.

Use of a grant-based mechanism that relies

on market transactions to redistribute produc-

tive assets is an innovative approach and the

strong reliance on decentralized mechanisms of

implementation generates a tremendous op-

portunity to learn from innovative practices

that are developed in some communities.

Careful monitoring is therefore essential to as-

sess the degree to which the program attains its

overall goals and to identify means for im-

proving on implementation. This is critical to

provide greater responsiveness to operational

diculties than has been available in practices.

Table 2 relates key components of monitoring

and impact evaluation to the issues discussed in

the municipal land reform plan.

To provide answers to these questions, it is

necessary to consider which instruments are

best suited to reach particular target groups,

maximize the net benets of land reform (or