Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Guidelines For Planning and Conducting Workshops and Seminars - 2

Caricato da

Aftab Mohammed0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

245 visualizzazioni40 pagineChecklist for organizing

Titolo originale

Guidelines for Planning and Conducting Workshops and Seminars_2

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoChecklist for organizing

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

245 visualizzazioni40 pagineGuidelines For Planning and Conducting Workshops and Seminars - 2

Caricato da

Aftab MohammedChecklist for organizing

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 40

GUIDELINES FOR PLANNING AND CONDUCTING WORKSHOPS & SEMINARS

THE OFFICE OF PUBLIC SECTOR REFORM

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................. 4

OBJECTIVES ................................................................................................................... 5

FRAME WORK ................................................................................................................ 6

Definition of a Seminar6

Definition of a Workshop....7

PROCESSES ..................................................................................................................... 8

PREPARATION ............................................................................................................. 8

BUDGET ..................................................................................................................... 9

THEME / TOPIC......................................................................................................... 9

SELECTION OF PRESENTER ................................................................................... 9

Points to consider: .................................................................................................... 10

TARGET GROUP ..................................................................................................... 10

SECURE VENUE ...................................................................................................... 11

Points to consider: .................................................................................................... 11

FINALIZE DETAILS ................................................................................................. 11

CONTACT RELEVANT DEPARTMENTS / PARTICIPANTS .................................. 12

FOLLOW UP ............................................................................................................ 12

PREPARE FINAL LIST OF PARTICIPANTS........................................................... 12

RESOURCES ............................................................................................................ 13

PAYMENT ................................................................................................................. 13

2

IMPLEMENTATION .................................................................................................... 14

SEATING ARRANGEMENTS .................................................................................... 16

CIRCLE: ................................................................................................................... 16

SEMICIRCLE: .......................................................................................................... 16

HERRINGBONE: ...................................................................................................... 17

THEATER: ................................................................................................................ 17

CLASSROOM: .......................................................................................................... 18

BANQUET, ROUNDS: ............................................................................................. 18

U-SHAPE: ................................................................................................................. 19

PRESENTATION STYLE............................................................................................ 20

Points to consider: .................................................................................................... 20

WORKSHOP METHODS ............................................................................................ 22

PRESENTING INFORMATION ............................................................................... 22

READING ................................................................................................................. 23

DEMONSTRATIONS AND DRAMATIC ENACTMENTS ........................................ 24

PRACTICE WITH FEEDBACK ................................................................................ 25

ELICITING AUDIENCE REACTIONS AND RESPONSES ..................................... 28

PROBLEM-SOLVING / CASE BASED LEARNING................................................. 32

UNPLANNED STRATEGIES .................................................................................... 33

VISUAL AIDS .............................................................................................................. 35

Points to consider: .................................................................................................... 35

EVALUATION ............................................................................................................... 37

Level I: Opinions and Satisfaction ............................................................................ 37

3

Level II: Competence Measures ................................................................................ 38

Level III: Performance .............................................................................................. 38

Level IV: Outcome Measures .................................................................................... 38

REFERENCES ................................................................................................................ 39

4

INTRODUCTION

Successful seminars / workshops are a direct result of adequate previous preparation on

the part of the organizer of the event. These events are costly and time consuming

endeavors, therefore it is of paramount importance that the event meets or exceeds its

desired objective of communicating the information presented to the selected target

group. Globalization and technology has given us the opportunity to conduct seminars /

workshops in a variety of ways, therefore, the resourceful organizer, whether in

government or private enterprise, should be vigilant and receptive to embrace theses

changes that occur in their working environment which can impact on their profitability,

efficiency and effectiveness.

This Paper will examine the guidelines for planning and conducting workshops and

seminars within the public sector as todays business environment places particular

emphasis on good practices that should be utilized by planners to achieve success.

Traditionally, workshop and seminars were conceived as being different types of training

devices, but in contemporary times, the two are seen as being synonymous and are used

interchangeably to refer to the same thing. For the purpose of this Paper, the latter

interpretation will be used.

5

OBJECTIVES

This Paper will seek to achieve its objective by:

Defining the words seminar and workshop

Determining the similarities and differences between a seminar and a workshop

Identifying the stages involved in planning a seminar / workshop

Outlining the steps involved in planning and conducting seminars and workshops

Decomposing the stages of a seminar / workshop

Identifying different seating arrangements

Outlining different presentation styles

Defining different visual aids

Defining evaluation levels

6

FRAME WORK

Workshops and seminars are among the most popular training devices in higher

education. When properly designed, they are a time and cost efficient method of

producing active involvement of learners compared to individual training activities.

Preparing a seminar / workshop involves understanding a wide variety of issues and

concerns. Each seminar / workshop has a unique audience with unique skills and

objectives, and perhaps a different number of participants. It is usually held in a different

place with a different infrastructure. Two seminars / workshops are never identical, even

if they cover the same topic. You don't want to be surprised when you arrive on site and

meet the participants.

Whether you are conducting a workshop / seminar your main goal is to communicate

your topic to an audience of mixed backgrounds and interests. Therefore, you should

present your information in a way that everyone can understand and leave with some

lesson learnt.

Definition of a Seminar:

Seminars are small group teaching and learning arrangements that use group interaction

as a means of engaging participants. Although seminars usually begin with a presentation

or mini-lecture to provide the basis for discussion, the word seminar also includes

rather formal group discussions led by the teacher and focused on the content rather than

on issues arising from students (J aques, 1991).

7

Definition of a Workshop:

Workshops are teaching and learning arrangements, usually in small groups, that are

structured to produce active participation in learning. Traditionally, workshops provide

participants with the opportunity to practice skills and receive feedback. However,

current usage is so loose that any learning event that aspires to engage the learners

actively may be called a workshop.

Workshops and seminars are similar in that they both are learning and teaching

arrangements which allow for active participation of participants, and they are usually

conducted in small groups. They differ in the practical application of the topic under

discussion. At a workshop, the participants are given the opportunity to practice skills

and receive feedback while a seminar concentrates on delivering the information and

discussion of the pertinent issues.

8

PROCESSES

There are a number of activities that are involved in preparing a seminar / workshop these

activities can be organized into three (3) stages:

1 Preparation

2 Implementation

3 Evaluation

PREPARATION

Preparation for the seminar / workshop involves a number of activities listed below:

1. Determine the budget available to host event

2. Determine the theme / topic to be discussed at the seminar / workshop

3. Contact and secure the relevant Presenter(s)

4. Identify target group and number of participants required

5. Secure venue (site visit of venue to ensure it is adequate)

6. Finalize event details (breaks, resources needed)

7. Contact relevant Ministries, Departments or target group to inform them of

event (time, date, venue, duration, break information)

8. Follow up on 6 to ensure the information was received

9. Finalize list of persons attending

10. Source and prepare all necessary resources needed by organizer and Presenter

(books, manuals, projectors, name tags, etc)

11. Secure caterer to provide meals if not included in venue package

12. Contact Accountant and request a Local Purchase Order

9

BUDGET

Funding is an integral part of any event, since the amount of funding available for the

hosting of the event will determine a number of factors in planning the event.

1. Venue

2. Duration

3. Number of participants

4. Equipment (Presentation Media)

5. Informational packets / Materials

6. Availability of refreshments

7. Expertise of Presenter

THEME / TOPIC

The seminar topic should address an issue / concern which has stimulated the interest of

the business sector or the wider society. The selection of the topic should naturally lead to

the seminar objective. The objectives in turn will determine the scope of the seminar and

should deal specifically with those areas that are pertinent to the achievement of the

seminar objectives.

SELECTION OF PRESENTER

The success of the seminar greatly depends upon the quality of the Presenters, therefore,

you should choose speakers whom are appropriate for the topic chosen. Ideally, the

speaker should be someone at the top of their field or someone who possesses an in-depth

knowledge of the particular area either academically or professionally. The Presenter

should be informed of the seminar scope and its desired objectives in order to facilitate

10

their preparation of the actual material they will be presenting. The material to be

presented should be accurate and up-to-date. This will undoubtedly influence the

equipment and visual media to be used in the presentation. Confirmation of speaker

participation should be sought at this point.

Points to consider:

1. Expertise / strong research background

2. Ability to convey knowledge to a large audience

3. Unbiased and non-partisan (do not invite speakers that are aligned with a

particular cause / group)

4. Honorarium

5. Travel expenses

6. Identify alternative speaker as a precaution

TARGET GROUP

The characteristics of participants will influence the structure, content and activities

undertaken in a workshop. Some key questions to be taken into consideration:

1. What is the size and the composition of the group?

2. What are the ages, ethnicity, gender and teaching experience of the

participants?

3. What is their level of interest?

4. What are their needs?

5. How to mitigate problems that might arise?

6. Personality types of group?

11

7. What is the best way to get the message across?

SECURE VENUE

The type of seminar being presented will influence the venue that is chosen. The

facilities of the venue should be able to comfortably accommodate the participants while

taking into consideration the needs of the Presenter and the budget.

Points to consider:

Cost

Capacity

Security

Computer accessibility

Lighting & Acoustics

Audio / visual requirements

Temperature

FINALIZE DETAILS

Determine the length of the seminar, the mode(s) of deliverance, equipment needs of

Presenter, handouts and other learning material for participants, breaks and refreshments,

and deadlines for replying. Secure a caterer to provide refreshments if not included in

venue package.

12

CONTACT RELEVANT DEPARTMENTS / PARTICIPANTS

Initial contact of those Departments or persons identified to attend the seminar, with the

full details of the seminar included.

Includes:

1. Deadline for response

2. Seminar overview / outline

3. Requirements for eligibility

4. Number of participants required

FOLLOW UP

Liaising with Departments / participants to ensure that the information disseminated by

the organizer was received. Ascertain the potential participants who are attending the

seminar and remind them of start date.

PREPARE FINAL LIST OF PARTICIPANTS

The final list of those persons attending the seminar is prepared. All relevant persons are

notified of the number of participants (Caterer, Presenter, and Facilitator).

13

RESOURCES

All resources required for the seminar is acquired or sourced at this stage.

Checklist:

Projectors, Laptop

Flip charts

Software Microsoft PowerPoint

Stationery markers, pens, notepads

Handouts

Name tags

PAYMENT

All bills should be paid before the commencement of the seminar to avoid any

embarrassing situations from occurring. The Local Purchase Order or other form of

payment should be finalized and be ready for disbursement, unless there is a special

arrangement for payment between the organizer and the recipient.

14

IMPLEMENTATION

This is the phase where the actual conducting of the seminar / workshop takes place.

1. Arrive early at venue to ensure the following:

Furniture is arranged as desired.

Name tags of participants are laid out.

Participants informational packets are laid out.

Equipment and material required by Presenter are ready and working.

Completion of Registration forms (if necessary).

2. Welcome address and introduction of Presenter:

The facilitator formally welcomes all participants to the seminar.

The facilitator gives a brief synopsis of the seminar.

Explanation of their role in the seminar.

Answers any queries the participants may have.

- The seminar time schedule

- Refreshment times and location

- What they are expected to do

- Planned activities that require their participation

Introduces the Presenter and gives an insight into his background.

Hands over the seminar to the Presenter.

15

3. Conducting the seminar

The Presenter should consider the following:

Seating arrangements

Presentation style

Workshop methods

Visual Aids

16

SEATING ARRANGEMENTS

CIRCLE:

Place chairs in a circle if interactive discussion of a fairly small group will be the

primary activity of the meeting.

SEMICIRCLE:

Semicircle provides all attendees good viewing and audience contact, and the

Presenter has high audience density with great eye contact. Since center aisles are

prime seating areas, the aisles are moved to the sides. All chairs face the

Presenter. Ideal, if a projection device, chalkboard or flip chart will be used.

17

HERRINGBONE:

Theater or classroom seating, positioned in angles or curves to face the stage. This

setup is both unique and functional. Each member of the audience can look

straight forward and have a good view of the stage. It's the next best thing to

Semicircle.

THEATER:

Straight rows of chairs facing the stage, without tables. It allows for the highest

audience density and keeps them closest to the front to create increased audience

responsiveness.

18

CLASSROOM:

Rows of chairs, as in theater, placed at long, narrow tables. The best tables

measure 18" x 6 or 8. You lose some audience density and seating capacity, but

gain comfort and writing ability for the attendees. For long seminars, this layout

works best.

BANQUET, ROUNDS:

A series of round tables set with 8-10 chairs. This is a good setup for meals and/or

networking among the people at the table. It has the drawback of severely limiting

seating capacity, spreading the audience too far from the stage, and forcing half

the audience to crane their neck or rotate their chairs.

19

U-SHAPE:

Rows of long, narrow tables shaped to form a "U". Best for interaction between

attendees as in a meeting, but least effective if you want attention placed on the

Presenter. The Presenter is always looking away from the majority of the

attendees and has a space gap between all of them.

20

PRESENTATION STYLE

The Presenter should seek to present the seminar in a smooth manner without sounding

too rehearsed.

Points to consider:

Learn your speech to avoid having to read it. A helpful technique is to

use cue card with a list of the main points to guide you.

Practice this is important for a successful presentation. It allows the

speaker to spot flaws and enables smoother transitions from section to

section. Try to rehearse with an audience of friends or peers to get

feedback and constructive criticism.

Dress Seek to look and act professional. Develop a confident (But not

arrogant) stage presence. Look at your audience and make eye contact

with them. This conveys an air of confidence and knowledge ability about

the subject matter.

Avoid doing any distracting mannerisms

Avoid showing your nervousness the internal nervousness most speakers

feel during presentations is usually not seen externally. It is a good idea to

familiarize yourself with the selected environment.

Speech speak loudly and clearly, as if to a person at the very back of the

room. Keep up the intensity of your voice right to the end of each

sentence. Show enthusiasm by varying the pitch of your voice since this

makes listening more interesting and gives you a tool for emphasizing. Do

21

not speak too fast and keep your sentences short. Main points should be

repeated to aid memory and understanding.

Time Management The Presenter should be aware of the time allocated

for the presentation and package his material to suit.

22

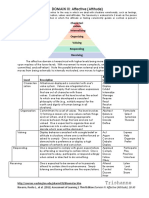

WORKSHOP METHODS

The methods used in the workshop must suit the objectives of the workshop.

Objectives can be classified as knowledge, skills or attitudes.

PRESENTING INFORMATION

1. Brief presentation followed by questions

This method works well when participants know enough about the topic to

generate stimulating questions.

2. Presentations with designated respondents

Assign specific tasks to various participants. You assign tasks that engage

the learners.

3. A panel discussion

This is an informal discussion among members of a selected group in front

of an audience. This method is suitable for teaching large groups where

there are too many people in the audience for audience interaction. Not

ideal for encouraging interaction in a small group.

4. A debate

This is an engaging method for presenting material since the participants

themselves take part. Debaters should be encouraged to focus on

23

convincing one another of their arguments rather than on discrediting or

attacking their opponents.

5. Prepared media

This method is used to stimulate conversation and not to replace it. A

popular form of videotaped presentation for use with small groups is the

trigger tape, a brief, dramatic presentation that triggers interaction

among participants. Slides or graphical information can be used in this

way.

READING

1. Requiring an assignment

Participants may be asked to take a position based on the readings or to

develop a case or example from their own practices.

2. Brief position papers

Participants may be required to write a position paper or statement (a few

paragraphs or one page) stating their position or response.

3. Reading during the workshop

Participants read brief assignments during the workshop, and then the

assignments are discussed or reported to the larger group.

24

4. J igsaw Technique

Participants read different assignments. Each assignment is designed to

bring out a separate component of the issue at hand. The participants in the

team then combine their knowledge to generate a complete picture of the

phenomenon. According to this technique, originally described by

Aronson et. al. (1978), the problem, question or assignment is divided into

parts and each part is parceled out to a different team, called the expert

teams. The first task of these teams is to make themselves expert at their

particular part of the problem. But they must also discuss how each of

them will teach what they know because, in the next phase of the process,

the expert teams regroup into home teams consisting of one member of

every expert team. The task of the home groups is to put together the

entire issue or solve the entire problem by combining the components.

DEMONSTRATIONS AND DRAMATIC ENACTMENTS

Demonstrations are useful as a component in skill learning to model either

proper or incorrect procedures. By themselves, they cannot teach skills

unless they are followed by actual practice by the participants, with

constructive feedback. Demonstrations can encourage learners by

convincing them of the effectiveness of a procedure.

25

PRACTICE WITH FEEDBACK

This method is the standard method of skills learning, including complex cognitive skills

like problem solving and critical thinking.

1. Helping Trios

The group divides into teams of three. One member of the team performs a

procedure (e.g. giving feedback to the other), while the third observes.

After the performance all three give feedback to one another. This process

is reiterated until everyone has taken each role, all of the triads join a

general discussion of the problems and issues involved in the targeted

performance. This method increases the active engagement of participants

to 100%.

2. Paired Interviewing

This method consists of a pair of learners who interview one another.

Learners who think that they understand something after reading about it

find that the task of being able to explain their understanding to someone

else requires a much deeper level of understanding and integration of the

material. The interviewer who is confused by the answer to his / her

question is providing indirect feedback to the questioner about the clarity

of the answer. After two pairs engage in this interviewing process they can

join one another to discuss problems of understanding the material. The

26

goal of this procedure is integration of knowledge, not the learning of

skills. This method was developed by Kagan (cited in Millis, 1995).

3. Testing One Another

This is one method (Sherman, 1991, cited in Millis, 1995) that takes the

pain out of learning from testing. Prior to the workshop each participant

prepares a question and a thorough answer. During the workshop

participants are organized into pairs and they exchange questions and

work independently for 20 minutes or so answering their partners

question. The two then compare their answers with those generated at the

workshop.

4. Videotape feedback

This is a useful aid in practice sessions, particularly when the target

behavior is visible on video.

5. Concentric Circles / Fish Bowl Technique

This method consists of a small circle of group members within a larger

circle. Members of the inner circle practice by interacting in some way

(problem solving, discussing, teaching) while the outer circle observes

them and provides feedback.

27

6. Separating the Idea Generating Phase from the Critical Phase

The group is broken into smaller groups, each of which addresses a

problem, question or an issue. They are encouraged to generate as many

solutions as possible but not to be critical of any of them. Each group

passes its solutions on to another whose task is to critically examine the

solutions offered for feasibility, cost effectiveness and to suggest ways

that the various solutions might be tested.

28

ELICITING AUDIENCE REACTIONS AND RESPONSES

1. Brainstorming

This is a creative thinking technique in which group members storm a

problem with their brains. A recorder lists the ideas while the leader keeps

vigilant to remind contributors when the rules are violated. The rules are:

no critical judgments until later; dont be concerned with quality of ideas,

quantity is all that counts; wild ideas are encouraged and improvements on

someone elses idea is legitimate. Only one participant can speak at a time.

2. Buzz Group

This technique is highly effective for getting participation from everyone

in the group. The leader divides the group into small clusters of three to

six and then provides each cluster with a question or two. A recorder in

each group reports to the larger group and a discussion usually follows. In

brainstorming only one participant can speak at a time, in buzz groups a

participant can be speaking in each cluster.

3. Think-Pair-Share

This technique was developed by Frank Lyman (Cited in Millis, 1995), it

allows more than one person to speak at the same time. In the first phase,

all of the participants are engaged in thinking about a problem or

question that the teacher presents. After a few minutes, participants are

invited to form pairs and share the problem with their partners. During

29

the third phase, learners can share their thoughts with larger groups or the

entire workshop.

4. Voting with your Feet / Stand up and be counted / Value Lines

There are several versions of this method, but one version developed by

Ivan Silver (1992) for use in a medical education context, is called Stand

Up and be Counted. Participants are given two minutes to write down

whether they agree or disagree with the way that a particular case or

problem was handled and their reasons. They are then asked to share their

thoughts with the participant next to them. In the third phase, participants

are asked to get up from their chairs and stand at the point in a line that

corresponds to their opinion on the issue. The facilitator draws a huge

Likert-type scale on the wall of the class marked at five points by the

words Strongly agree, disagree, dont know, agree and strongly

disagree. If the class is too large for the size of the wall available, the

facilitator asks for half or a quarter of the class at one time. The facilitator

then interviews participants to find out why they chose their particular

position in the line. For about 10 or 15 minutes the facilitator encourages a

debate, beginning with those at opposite ends of the line. The debate is

gradually widened to include others at various places on the line and those

who are seated. Finally, the facilitator asks everyone to sit and he

summarizes the discussion.

30

Another version, called Value Lines is described by Barbara Millis in

the Teaching at UNL newsletter, (1994). In this version there are two

anchors, one at each end, such as Strong disagreement and strong

agreement. Persons are invited to share their ideas with others at different

points on the line or opposite ends may be invited to pair up.

5. Card-Sorting

A card-sorting game called Do You Have Any Fives? developed by

Ivan Silver and Nathan Hermann (1996) provides an opportunity for all

participants to test their knowledge by placing cards in the appropriate

categories and by teaching one another. At the start of the game each

participant has in front of him or her, a pile of twenty to thirty cards that

he or she must sort into four to six categories. Each card has a

characteristic written on it that more accurately describes one of the

categories than the others. Participants would then explain to others why

they chose that category for this particular card. After participants have

sorted all the cards into categories, the facilitator will review all the cards

in the categories, and make necessary corrections by providing additional

information and explanations.

6. Writing

This method of eliciting responses from the learners and ensuring their

engagement in the task is the use of a reaction sheet. Sheets of paper

31

with instructions to answer a few questions are distributed to the group at

an appropriate moment. Typically, they ask questions designed to elicit

useful feedback from the participants about their learning: Write down

ideas that are new to you; Ideas that you question; Ideas that really hit

home, for whatever reason.

7. Group Leader Skills Active Listening

This guide focuses on exercises that can be conducted in class. A skilled

group leader can make a huge difference to the willingness of participants

to share their thoughts and feelings.

32

PROBLEM-SOLVING / CASE BASED LEARNING

1. Structured Case / Problem Scenario

A case or problem scenario is presented to the whole group or, if the group is large, to

subgroups of three or four. After the groups discuss the problem for 5 or 10 minutes, the

teacher goes around the room listening to their solutions, approaches, conclusions.

2. Variation 1.: Random Reporting

One weakness of this procedure is that the more assertive learners nearly always become

the reporters for the group. Another weakness is that some learners who do not fully

understand the solutions or conclusions offered by their group might not catch up. A

modification of this method, described by Barbara Millis (1995) overcomes the problem:

once the group has discussed the question or solved the problem they are required to

make certain that every group member can summarize the groups conclusions. The

teacher goes from one subgroup to another calling on one of its members at random and

asking her or him to report to the entire workshop. Those chosen to report are less

inhibited because they are reporting the group consensus rather than their own views.

3. Variation 2.: The J igsaw Technique

As discussed previously

4. Dramatic Enactment

As discussed previously

33

5. Problem-based-learning

As practiced in most medical schools, this material is too time-consuming for the typical

workshop. In the course of tackling the problem, participants identify gaps in their

knowledge or understanding which they then fill by individual study and by sharing

information with their peers. Workshops and seminars can use this method but the

materials must be prepared and available for the group participants.

6. Case-Based Learning

This method was developed in the Harvard School of Business and is carried out in

relatively large classes, sixty or so. But it can be adapted easily to a workshop format.

First, a number of subgroups read a rather detailed case and discuss it. Their task is to

develop a response to questions posed by the case. Then, all of the subgroups come

together for a kind of debate about what is the best course of action. The teacher points to

individuals and asks each of them, What would you do in this situation? The large

group sessions can become highly confrontational as individuals are intentionally pitted

against one another by a skillful teacher. In the workshop situation, it would be better to

pit subgroups against one another rather than individuals. Letting groups rather than

individuals argue about the best course of action produces a safer interpersonal climate.

UNPLANNED STRATEGIES

Opportunities may arise for spontaneous interventions during the workshop. For example,

you may notice an example of the phenomenon that you are trying to teach within the

34

learning group itself. Pointing out such parallels is a powerful strategy for connecting the

lesson to the real context of the learners.

35

VISUAL AIDS

A visual aid is something your audience can see that aids your speech content. Visuals

should be proof read to ensure there are no errors or discrepancies.

Points to consider:

Font

The font should be big enough to be seen from the back of the venue.

Titles should be in a larger font than the body of the information. Keep

similar text the same size from one visual to the next.

Color

Care should be taken in choosing the colors for your presentation

especially, if you will be using slides. The tried and proven colors for

slides are white on blue and black on white.

Background

The background should form a contrast in relation to the text used.

Layout

The slide should not be overcrowded with information. Information should

be spaced so that it is easy to read.

36

Text

Use point form or short simple phrases instead of sentences or paragraphs.

Using all capital is harder to read therefore use a combination of upper and

lower case lettering. Each visual should have:

- One main point

- One thought per line

- No more than 5-7 words per line

- No more than 5-7 lines per visual

Graphs and Tables

Graphs and tables are the best way to summarize large quantities of raw

data. You should note the following:

- Simplify the data

- Show only the essential information

- Be consistent in style and terminology, font, color

- Data elements should be the thickest and the brightest colors.

Frames, grid lines, axis lines, and error bars should be lighter in

color and weight

- X and Y axis lines should end at the last data point

- Include legends

37

EVALUATION

An evaluation is an important part of any workshop for two reasons. First, evaluations

provide concrete feedback to the facilitator about how the workshop was received. This

information should be considered in the planning of future workshops. Second,

evaluations require the participants to reflect upon the workshop, including the

facilitation, content, processes, facilities, how they might use what they have learnt, etc.

An evaluation process which allows you as the facilitator to participate would continue

the process of sharing and group activity which should have been established through the

workshop.

The following steps are levels of evaluation taken from Dixon, 1978:

Level I: Opinions and Satisfaction

The most common means of evaluating workshops are attendance plus a measure of

customer satisfaction, a questionnaire composed of rating scale items asking participants

whether they got what they expected, what they learnt and whether they think it will be

useful in the real setting. Qualitative methods, including focus groups or individual

interviews, can provide the opportunity for participants to raise unanticipated issues.

Attendance and satisfaction are usually accepted as evidence by administrators and

workshop planners of the successfulness of a workshop. But, sometimes, the customer

does not know best. Participants can be overly optimistic about the value of new learning

while still feeling the high of an exciting workshop. A delayed measure may provide a

more accurate reflection of the workshop participants satisfaction. Questionnaires sent to

38

participants several weeks or months after the workshop may provide a more accurate

measure of the impact of the workshop.

Level II: Competence Measures

Quantitative measures of competence include measures of knowledge, skills and attitudes

using instruments such as multiple choice exams and OSCE stations. Qualitative

measures include attitude assessing questionnaires and interviews.

Level III: Performance

In the health professions, performance might be measured by quantitative indices such as

prescribing data and x-ray utilization or, qualitative indices, such as explorations of

barriers to change and chart stimulated recall.

Level IV: Outcome Measures

Evaluation of the behaviour, that is, the target of the workshop, under conditions as

similar as possible to those in the real setting. The actual impact of the learned behaviour

in the real setting may be the gold standard, but it is difficult to measure because of the

problems of isolating the impact of the workshop from all of the other variables that

effect the real environment. Moreover, the workshop may be successful in the sense that

participants learn the skills, but still they may not be transferred to the workplace because

of adverse conditions there.

39

REFERENCES

Coastal and Marine Studies in Australia: A Workshop Manual for Teachers

Conducting Effective Workshops

Griffith University and the Department of the Environment, Sport & Territories, 1997

ISBN 0 868 57872 X

http://www.deh.gov.au/education/publications/cms/guidelines.html#conducting

Coastal and Marine Studies in Australia: A Workshop Manual for Teachers

Workshop Format

Griffith University and the Department of the Environment, Sport & Territories, 1997

ISBN 0 868 57872 X

http://www.deh.gov.au/education/publications/cms/guidelines.html#wor

Conference Program Proposals Guidelines & Criteria

http://arlis2001.ucsd.edu/procrit.html

Giving A Talk Guidelines For The Preparation and Presentation Of Technical

Seminars Frank R. Kschischang

http://www.comm.toronto.edu/~frank/guide/guide0.html

Guidelines for Conducting Workshops and Seminars That Actively Engage

Participants.

February, 2001 Richard Tiberius and Ivan Silver Department of Psychiatry, University

of Toronto

http://www.hsc.wvu.edu/aap/aap-car/faculty-development/teaching-

skills/guidelines_for_conducting_workshops_%282001%29.htm

40

Guidelines For Proposal Submission: Workshops

http://www.cs.swarthmore.edu/~meeden/SIGCSE/workshop.html

Guidelines For Seminars

http://www.uwo.ca/biophysics/dept_forms/guidelines_seminar.pdf

Guidelines for contact making seminars

http://youth.cec.eu.int/studies/Contact%20Making%20Seminars/Contact%20making%20

seminarsW97.doc

Guidelines For Effective Tutor Workshops

http://www.dreamscape.com/deborah/laubach/LLA/Trainers/guidelin.htm

How To Sponsor A Successful Real Estate Seminar David Knox & Brenda Riner

http://www.davidknox.com/seminars/manual/manual_XI.html

Sharing The Results Of Your Scholarship With Your Colleagues

http://www.clt.uts.edu.au/Scholarship/Seminar.presentation.htm

Suggestions And Guidelines For Developing Your Seminar

http://www.foodsci.rutgers.edu/gseminar/Guidelines%20for%20Development%20Semin

ar.htm

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Converting Units of Measure PDFDocumento23 pagineConverting Units of Measure PDFM Faisal ChNessuna valutazione finora

- Brittney Gilliam, Et Al., v. City of Aurora, Et Al.Documento42 pagineBrittney Gilliam, Et Al., v. City of Aurora, Et Al.Michael_Roberts2019Nessuna valutazione finora

- Teachers Guide Pre KDocumento28 pagineTeachers Guide Pre KAftab MohammedNessuna valutazione finora

- Gagne's 9 Events of Instruction: A Guide to Effective PedagogyDocumento13 pagineGagne's 9 Events of Instruction: A Guide to Effective PedagogySeun Oyekola100% (2)

- Camp Greene: A Summer Day Camp Program GuideDocumento32 pagineCamp Greene: A Summer Day Camp Program Guideapi-551810918Nessuna valutazione finora

- Employee Feedback TemplateDocumento2 pagineEmployee Feedback TemplateSrinivas NuthalapatiNessuna valutazione finora

- Training of Trainers Manual-2Documento82 pagineTraining of Trainers Manual-2sethasarakmonyNessuna valutazione finora

- Nicolas-Lewis vs. ComelecDocumento3 pagineNicolas-Lewis vs. ComelecJessamine OrioqueNessuna valutazione finora

- TENNIS Practice Plan PDFDocumento128 pagineTENNIS Practice Plan PDFAftab Mohammed100% (3)

- TENNIS Practice Plan PDFDocumento128 pagineTENNIS Practice Plan PDFAftab Mohammed100% (3)

- Designing WorkshopsDocumento82 pagineDesigning WorkshopsGucciGrumps100% (1)

- Engaging Students: Active Learning Strategies in The College ClassroomDocumento13 pagineEngaging Students: Active Learning Strategies in The College Classroomamsubra8874100% (1)

- CoRT 1 ToolsDocumento19 pagineCoRT 1 Toolsspaceship7Nessuna valutazione finora

- Hem Tiwari Vs Nidhi Tiwari Mutual Divorce - Revised VersionDocumento33 pagineHem Tiwari Vs Nidhi Tiwari Mutual Divorce - Revised VersionKesar Singh SawhneyNessuna valutazione finora

- 5 4as OF LESSON PLANNINGDocumento25 pagine5 4as OF LESSON PLANNINGYvonne Alonzo De BelenNessuna valutazione finora

- Adult Learning Theory and PrinciplesDocumento3 pagineAdult Learning Theory and Principlessupriyasawant92Nessuna valutazione finora

- Net Ionic EquationsDocumento8 pagineNet Ionic EquationsCarl Agape DavisNessuna valutazione finora

- Employability Skills for Cooperative EducationDocumento19 pagineEmployability Skills for Cooperative EducationAnton FatoniNessuna valutazione finora

- Learning StylesDocumento12 pagineLearning StylesSafaa Mohamed0% (1)

- Essential Steps to Developing an Effective CurriculumDocumento10 pagineEssential Steps to Developing an Effective CurriculumTulika BansalNessuna valutazione finora

- What Is Active LearningDocumento17 pagineWhat Is Active LearningGedionNessuna valutazione finora

- Customer Satisfaction-Credit Card Holders SE Bank PDFDocumento112 pagineCustomer Satisfaction-Credit Card Holders SE Bank PDFAftab MohammedNessuna valutazione finora

- 14 - Habeas Corpus PetitionDocumento4 pagine14 - Habeas Corpus PetitionJalaj AgarwalNessuna valutazione finora

- Richard Herrmann-Fractional Calculus - An Introduction For Physicists-World Scientific (2011)Documento274 pagineRichard Herrmann-Fractional Calculus - An Introduction For Physicists-World Scientific (2011)Juan Manuel ContrerasNessuna valutazione finora

- The Ice Breaker: ProjectDocumento4 pagineThe Ice Breaker: ProjectgwilkieNessuna valutazione finora

- Topic 8: Teacher Professional Development and Life Long LearningDocumento22 pagineTopic 8: Teacher Professional Development and Life Long LearningAnas MazalanNessuna valutazione finora

- Experiential Learning StylesDocumento9 pagineExperiential Learning StylesMarquesNessuna valutazione finora

- Learning ObjectivesDocumento14 pagineLearning ObjectivesDUMO, AMY C.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Pearson BTEC Level 3 Performing Arts - Unit 13 - Contemporary Theatre PerformanceDocumento11 paginePearson BTEC Level 3 Performing Arts - Unit 13 - Contemporary Theatre Performancestuart_murray_22Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Six Facets of UnderstandingDocumento3 pagineThe Six Facets of UnderstandingRiz GetapalNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson Planning Guide for TeachersDocumento26 pagineLesson Planning Guide for TeachersAlee MumtazNessuna valutazione finora

- 20.1 A - Week 11 - Coaching and Performance LeadershipDocumento37 pagine20.1 A - Week 11 - Coaching and Performance LeadershipVI Nguyen Le ThuyNessuna valutazione finora

- Health EconomicsDocumento114 pagineHealth EconomicsGeneva Ruz BinuyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Three Domains of LearningDocumento9 pagineThree Domains of LearningpeterNessuna valutazione finora

- Conducting A WorkshopDocumento19 pagineConducting A WorkshopAnand GovindarajanNessuna valutazione finora

- ML Performance Improvement CheatsheetDocumento11 pagineML Performance Improvement Cheatsheetrahulsukhija100% (1)

- Instructions For Using This Course Syllabus TemplateDocumento8 pagineInstructions For Using This Course Syllabus Templateapi-296972124Nessuna valutazione finora

- DECA RolePlayDocumento6 pagineDECA RolePlayAftab MohammedNessuna valutazione finora

- Applied NLP Course OutlineDocumento2 pagineApplied NLP Course OutlineHarry SidhuNessuna valutazione finora

- Edhp 500 Summary of Learning Theories ChartDocumento5 pagineEdhp 500 Summary of Learning Theories Chartapi-254318672Nessuna valutazione finora

- Evaluation Presentation 21Documento57 pagineEvaluation Presentation 21api-211063572Nessuna valutazione finora

- Week 9 Teaching Approach, Strategy and MethodsDocumento35 pagineWeek 9 Teaching Approach, Strategy and MethodsTESL10620 Aida Nur Athilah Binti Mat SohNessuna valutazione finora

- Ethics of Communication PDFDocumento2 pagineEthics of Communication PDFBryan0% (3)

- Ashforth & Mael 1989 Social Identity Theory and The OrganizationDocumento21 pagineAshforth & Mael 1989 Social Identity Theory and The Organizationhoorie100% (1)

- Teaching MethodsDocumento55 pagineTeaching MethodsPriyanka BhatNessuna valutazione finora

- 317 Midterm QuizDocumento5 pagine317 Midterm QuizNikoruNessuna valutazione finora

- Manager-Employee Performance ReviewDocumento8 pagineManager-Employee Performance ReviewAftab MohammedNessuna valutazione finora

- Manager-Employee Performance ReviewDocumento8 pagineManager-Employee Performance ReviewAftab MohammedNessuna valutazione finora

- Manager-Employee Performance ReviewDocumento8 pagineManager-Employee Performance ReviewAftab MohammedNessuna valutazione finora

- Nestle RoadmapDocumento2 pagineNestle RoadmapAftab MohammedNessuna valutazione finora

- Final Report - Priority Vocational SkillsDocumento224 pagineFinal Report - Priority Vocational SkillsAhmad Rizal SatmiNessuna valutazione finora

- Customers' Satisfaction with Standard Chartered Bank's Service QualityDocumento55 pagineCustomers' Satisfaction with Standard Chartered Bank's Service QualityAftab MohammedNessuna valutazione finora

- Customers' Satisfaction with Standard Chartered Bank's Service QualityDocumento55 pagineCustomers' Satisfaction with Standard Chartered Bank's Service QualityAftab MohammedNessuna valutazione finora

- Trishanne: DOMAIN III: Affective (Attitude)Documento2 pagineTrishanne: DOMAIN III: Affective (Attitude)ᜆ᜔ᜇᜒᜐ᜔ᜑ᜔ ᜀᜈ᜔Nessuna valutazione finora

- Flipped Classroom Workshop - Facilitators GuideDocumento17 pagineFlipped Classroom Workshop - Facilitators Guideapi-354511981Nessuna valutazione finora

- Curriculum Development Module 8Documento3 pagineCurriculum Development Module 8Jane Ariane TilloNessuna valutazione finora

- Blooms Taxonomy Final DraftDocumento14 pagineBlooms Taxonomy Final DraftMark Rollins0% (1)

- Key Principles of Curriculum Alignment - AUN 2016Documento2 pagineKey Principles of Curriculum Alignment - AUN 2016cunmaikhanhNessuna valutazione finora

- Hpe2203 FPD Week 4Documento3 pagineHpe2203 FPD Week 4api-313469173100% (1)

- Appendix B: Suggested OBE Learning Program For EDUCATIONAL TECHNOLOGY 1Documento7 pagineAppendix B: Suggested OBE Learning Program For EDUCATIONAL TECHNOLOGY 1Albert Magno Caoile100% (1)

- Peer Coaching ModelsDocumento9 paginePeer Coaching ModelsCesar MartinezNessuna valutazione finora

- Assessment For Learning: Effective FeedbackDocumento15 pagineAssessment For Learning: Effective FeedbackZuraida Hanim ZainiNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson Plan 2Documento3 pagineLesson Plan 2api-318497844Nessuna valutazione finora

- Is a Teacher Really a Facilitator? The Case for Independent LearningDocumento3 pagineIs a Teacher Really a Facilitator? The Case for Independent LearningSanjay ShindeNessuna valutazione finora

- Technology Integration Lesson Plan 1Documento4 pagineTechnology Integration Lesson Plan 1api-320427440Nessuna valutazione finora

- Health Profession’s Education Assessment in Higher EdDocumento7 pagineHealth Profession’s Education Assessment in Higher EdnajamaneelNessuna valutazione finora

- Bloom's Revised Taxonomy - in A Nutshell: Judy Sargent, Ph.D. CESA 7 School Improvement ServicesDocumento37 pagineBloom's Revised Taxonomy - in A Nutshell: Judy Sargent, Ph.D. CESA 7 School Improvement ServicesRamyres DavidNessuna valutazione finora

- Reflection in ActionDocumento6 pagineReflection in ActionDarakhshan Fatima/TCHR/BKDCNessuna valutazione finora

- 2021 Life Skills Atp Grade 2Documento43 pagine2021 Life Skills Atp Grade 2Nanikie Ankie Moatshe100% (1)

- Formative assessment on ethics situationsDocumento3 pagineFormative assessment on ethics situationsMaryrose Sumulong100% (1)

- Jean Piaget and Lawrence Kohlberg: Cognitive and Moral Development TheoriesDocumento4 pagineJean Piaget and Lawrence Kohlberg: Cognitive and Moral Development TheoriesToffee Perez100% (1)

- A Guide To Implementing Lesson StudyDocumento83 pagineA Guide To Implementing Lesson Studyupsid033538Nessuna valutazione finora

- Teaching Psychomotor SkillsDocumento3 pagineTeaching Psychomotor SkillsjovenlouNessuna valutazione finora

- Instructional Design and Materials Evaluation FormDocumento3 pagineInstructional Design and Materials Evaluation Formzamir hussainNessuna valutazione finora

- Seminars RubricDocumento2 pagineSeminars RubricDunhill Jan100% (1)

- Interprofessional LearningDocumento6 pagineInterprofessional Learningrjt903Nessuna valutazione finora

- Building Good Work RelationshipsDocumento3 pagineBuilding Good Work RelationshipsAbdul PrinceNessuna valutazione finora

- Competency Based Education....... AmritaDocumento3 pagineCompetency Based Education....... AmritaGurinder GillNessuna valutazione finora

- Assignment MemoDocumento2 pagineAssignment MemoPRACHI DASNessuna valutazione finora

- Elearning Developer Instructional Designer in New York NY Resume Michael ForbesDocumento2 pagineElearning Developer Instructional Designer in New York NY Resume Michael ForbesMichaelForbesNessuna valutazione finora

- The Ultimate Guide to Creating Awesome KahootsDocumento43 pagineThe Ultimate Guide to Creating Awesome KahootsHugoNessuna valutazione finora

- IMC BrochureDocumento2 pagineIMC BrochureAftab MohammedNessuna valutazione finora

- P&G Corporate BrochureDocumento16 pagineP&G Corporate BrochureAftab MohammedNessuna valutazione finora

- BANK ONE BackgroundDocumento7 pagineBANK ONE BackgroundAftab MohammedNessuna valutazione finora

- Dev Camps (Bangladesh) - REGISTRATIONDocumento22 pagineDev Camps (Bangladesh) - REGISTRATIONAftab MohammedNessuna valutazione finora

- BUS601 Case Study InformationDocumento2 pagineBUS601 Case Study InformationAftab MohammedNessuna valutazione finora

- Powerfully Creative Hand Hygiene AdsDocumento13 paginePowerfully Creative Hand Hygiene AdsAftab MohammedNessuna valutazione finora

- BANK ONE BackgroundDocumento7 pagineBANK ONE BackgroundAftab MohammedNessuna valutazione finora

- Birth RegistrationDocumento5 pagineBirth RegistrationAftab MohammedNessuna valutazione finora

- HRM 380-Case-C-2-1-2-Caded Uniform PDFDocumento7 pagineHRM 380-Case-C-2-1-2-Caded Uniform PDFAftab MohammedNessuna valutazione finora

- EventsPlanningChecklist 1107Documento9 pagineEventsPlanningChecklist 1107Aftab MohammedNessuna valutazione finora

- BANK ONE BackgroundDocumento7 pagineBANK ONE BackgroundAftab MohammedNessuna valutazione finora

- Human Resource ManagementDocumento36 pagineHuman Resource ManagementAftab MohammedNessuna valutazione finora

- Customer Satisfaction-BRAC BankDocumento30 pagineCustomer Satisfaction-BRAC BankAftab MohammedNessuna valutazione finora

- Berger Paint ProjectDocumento144 pagineBerger Paint ProjectMukesh Kumar100% (2)

- Ratio AnalysisDocumento3 pagineRatio AnalysisAftab MohammedNessuna valutazione finora

- Ratio Analysis On Pharmaceuticals IndustryDocumento13 pagineRatio Analysis On Pharmaceuticals IndustryAftab MohammedNessuna valutazione finora

- Study On LIC IndiaDocumento9 pagineStudy On LIC IndiaAftab MohammedNessuna valutazione finora

- Customising PDFDocumento14 pagineCustomising PDFAftab MohammedNessuna valutazione finora

- Jaimini Astrology - Calculation of Mandook Dasha With A Case StudyDocumento6 pagineJaimini Astrology - Calculation of Mandook Dasha With A Case StudyANTHONY WRITER100% (3)

- De Broglie's Hypothesis: Wave-Particle DualityDocumento4 pagineDe Broglie's Hypothesis: Wave-Particle DualityAvinash Singh PatelNessuna valutazione finora

- Course Outline Physics EducationDocumento3 pagineCourse Outline Physics EducationTrisna HawuNessuna valutazione finora

- 202002Documento32 pagine202002Shyam SundarNessuna valutazione finora

- New GK PDFDocumento3 pagineNew GK PDFkbkwebsNessuna valutazione finora

- Cronograma Ingles I v2Documento1 paginaCronograma Ingles I v2Ariana GarciaNessuna valutazione finora

- Critters Table MannersDocumento3 pagineCritters Table Mannersapi-248006371Nessuna valutazione finora

- International Journal of Current Advanced Research International Journal of Current Advanced ResearchDocumento4 pagineInternational Journal of Current Advanced Research International Journal of Current Advanced Researchsoumya mahantiNessuna valutazione finora

- Social Marketing PlanDocumento25 pagineSocial Marketing PlanChristophorus HariyadiNessuna valutazione finora

- Court Testimony-WpsDocumento3 pagineCourt Testimony-WpsCrisanto HernandezNessuna valutazione finora

- Jason A Brown: 1374 Cabin Creek Drive, Nicholson, GA 30565Documento3 pagineJason A Brown: 1374 Cabin Creek Drive, Nicholson, GA 30565Jason BrownNessuna valutazione finora

- SLE On TeamworkDocumento9 pagineSLE On TeamworkAquino Samuel Jr.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Reviews: Bariatric and Metabolic Surgery: A Shift in Eligibility and Success CriteriaDocumento13 pagineReviews: Bariatric and Metabolic Surgery: A Shift in Eligibility and Success CriteriaJulia SCNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 CH - 7 - WKSHTDocumento8 pagine1 CH - 7 - WKSHTJohnNessuna valutazione finora

- Absolute TowersDocumento11 pagineAbsolute TowersSandi Harlan100% (1)

- Araminta Spook My Haunted House ExtractDocumento14 pagineAraminta Spook My Haunted House Extractsenuthmi dihansaNessuna valutazione finora

- FortiMail Log Message Reference v300Documento92 pagineFortiMail Log Message Reference v300Ronald Vega VilchezNessuna valutazione finora

- My Testament On The Fabiana Arejola M...Documento17 pagineMy Testament On The Fabiana Arejola M...Jaime G. Arejola100% (1)

- Development of Branchial ArchesDocumento4 pagineDevelopment of Branchial ArchesFidz LiankoNessuna valutazione finora