Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Man and Cannabis in Africa: A Study of Diffusion - Journal of African Economic History (1976)

Caricato da

AbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-Misri0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

110 visualizzazioni20 pagineMan and Cannabis in Africa: A Study of Diffusion - Journal of African Economic History (1976)

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoMan and Cannabis in Africa: A Study of Diffusion - Journal of African Economic History (1976)

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

110 visualizzazioni20 pagineMan and Cannabis in Africa: A Study of Diffusion - Journal of African Economic History (1976)

Caricato da

AbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-MisriMan and Cannabis in Africa: A Study of Diffusion - Journal of African Economic History (1976)

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 20

African Studies Program, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Regents of the University of Wisconsin System

Man and Cannabis in Africa: A Study of Diffusion

Author(s): Brian M. du Toit

Source: African Economic History, No. 1 (Spring, 1976), pp. 17-35

Published by: African Studies Program, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4617576 .

Accessed: 22/08/2013 17:40

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

.

African Studies Program, University of Wisconsin-Madison and Regents of the University of Wisconsin System

are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to African Economic History.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 71.172.230.211 on Thu, 22 Aug 2013 17:40:27 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

17

Man and

Cannable

in Africa: A

Studg

of

Diffuesion

Brian

M. du Toit

University of Florida

The

past

decade has seen an

awakening

of research interests

regard-

ing psychoactive

and

hallucinogenic drugs.

While the New World is

par-

ticularly

rich in these natural

products,

no

drug

has as wide a distri-

bution nor as universal an

appeal

as cannabis. This

hallucinogen

is

known

by

different local referrents but the most

widely

distributed is

marijuana

in the United States and Latin

America,

and

hemp

or Indian

hemp

in

many

of the other

Anglophone

areas of the world. While it has

near universal

distribution,

it is nonetheless to the Old World we must

look for its

origin

and

original acceptance.

Cannabis was

originally

cultivated as a fiber

plant

and

only

its

leaves were used in the

pharmacopoeia

of different

peoples.

Linnaeus

classified it as a

simple species

Cannabis

sativa,

but "recent research

indicates that there

may

well be several

species."'1

At this

stage

we

are not concerned with this botanical

question

but intend to focus on

the social use and diffusion of the

plant through

Africa.

In this

paper

we will examine in turn the

historical, sociological,

and

linguistic

evidence

relating

to the cannabis

plant

in Africa.

Then,

after a brief review of current

hypotheses regarding

the diffusion of

cannabis,

we will

propose

a more

encompassing hypothesis

to account for

its

spread

in sub-Saharan Africa.

HISTORICAL EVIDENCE

The

early trading

contacts between India and the Arabian Penin-

sula,

as well as trade and settlement

by

Indian and Arabian merchants

started around the

Horn,

but soon extended southward

along

the east

African coast.

Early

trade links between Arabia and the east African

coast are well documented and were

flourishing by

the first centuries

A.D. Doubtless such

trading

involved valued

products

from

India,

Turkey,

and Persia in

exchange

for

minerals, precious stones,

and

ivory.

According

to classical sources an Arabian trade center existed at

Rhapta

and in time settlers and traders

spread southward, along

the coast.

Neville Chittick

reports

that

by

the eleventh or twelfth

century

Muslim settlements could be found on Zanzibar and

Pemba,

and also at

Kilwa.2

The same author

suggested

that

"By

the

early

tenth

century

A.D.

(al-Mas'udi),

there were Muslims in

Qanbalu (Pemba?)

and there were

already

Bantu settled in this zone.

By

the mid-twelfth

century (al-

Idrisi),

most the inhabitants of Zanzibar were

Muslim;

there were num-

bers of towns on the

mainland,

most of which

appear

to have been

pagan,"3

and there was close contact between these settlers and Bantu

speakers.

This is also the

period during

which cannabis

spread

westward

from

India and Persia to

Egypt.4

African Economic

History, Spring,

1976.

This content downloaded from 71.172.230.211 on Thu, 22 Aug 2013 17:40:27 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

18

Ahmad

Khalifa, referring

to Arabic

historians,

stated that cannabis

was introduced into

Egypt during

the

reign

of the

Ayyubid dynasty,

around

the mid-twelfth

century;

"as a result of the

emigration

of

mystic

devo-

tees from

Syria.5

We

might

then

suggest

that the Arab communities on

the African east coast were associated with

cannabis,

either in the form

of the domesticated

variety

used for its

fiber,

or the wild

variety

which

was used as medication and as a

mind-altering

substance.

Much of the trade with the interior

regions

of Africa was

by

ascent

through

river

valleys

but these

frequently

were rendered

impassible

during

the

rainy season,

thus

necessitating

extended

periods

of

stay

in

the interior. A.McMartin6 in fact

suggests

that at various inland centers

the Arabs had

semi-permanent

settlements where

they

would

spend

one or

two

years away

from the coast. When the

Portuguese

made their

way up

the Zambezi in 1531 to establish a

trading post,

a small Arab

community

existed at

Sena,

almost a hundred miles from the coast.7 Based on ethno-

historical

sources,

D. P. Abraham has estimated that at the start of the

sixteenth

century

at least ten thousand Arabs were in Rhodesia

tapping

the

wealth of the Zimbabwe settlers in Rhodesia.8 In time

they

had a

great

influence over the

Karanga territory--an

influence

they

later

exchanged

with the

Portuguese

who traded from their new base in

Mozambique.

Two

centuries later David

Livingstone

commented on the

presence

of Arab

traders and Arab influences in wide areas of central Africa.

We need not

overemphasize

the

presence

of the Arab traders in the

interior. At the time when the first Arab settlements were

being

estab-

lished off the east African

coast,

and the

gold

trade with Sofala was

being regularized,9

there were

already Bantu-speaking peoples

in contact

with them. These

Bantu-speakers

were

gradually spreading

southward as

they expanded

their

territory

or

grazed

their cattle. As far back as

the second and third centuries A.D.

imports

were

reaching

central Africa

via

indigenous

trade

routes,10

or

spreading

further westward

along

an

extensive series of trade routes into the

Congo

basin11

or,

more

likely,

conveyed by Swahili-speaking

traders into the Great Lakes

region.

In a

discussion of excavations of sites on Lake Kisale in northern

Katanga,

Jacques Neguin postulates

a date of the seventh to the ninth

century

A.D.

for them and states that "the

perforated

cowrie shell found in Burial 54

probably

comes from the East Coast."12 This is one of

many suggestions

by

research workers

regarding

trade contacts at an

early date,

but more

important,

trade contacts from east to west. Further south there is

documentation of similar

indigenous trade,

for around 1835 "the Matabele

had considerable traffic with the

Amasili/Masarwa

off the

edge

of the

Kalahari, exchanging iron, daggo (sic), spears, hoes,

and knives for

ostrich

eggshell beads, ivory, feathers,

horns and skins."13

The same kind of trade into the Kalahari

region

from the

peoples

in South West Africa also

existed,

as did various trade lihks

among

the

local

populations

who cultivated and used cannabis. H. Vedder

(1928)13a

emphasized

the value of cannabis as

currency

in transactions

where,

for

example,

the

Bergdama

who cultivated the

herb,

traded it to the Ovambo

for

goats

and cows. In fact it was "the

Bergdama's money

with which

they

could

buy everything they

needed." In what later became South

Africa we have earlier and better documented evidence of the

presence

14

of

cannabis, though

it was

frequently

confused with Leonotis leonurus.

The inclusion of cannabis in the list of trade items between Khoikhoi

This content downloaded from 71.172.230.211 on Thu, 22 Aug 2013 17:40:27 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

19

and

Bantu-speakers

on the east coast has been discussed elsewherel5

though

it would seem that some

groups among

the

Khoikhoi, particularly

the

Hankumqua, may

have cultivated this herb. In addition to the Khoi-

khoi the San hunters both usedl6 and traded17 cannabis. In

fact,

when

Whites settled at the southern

tip

of the African continent cannabis

was in common use. We will return to this

question

when

dealing

with

the

linguistic argument

below.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL DATA

That Iron

Age

Africans were

cultivating

in the Zambezi

valley

and

raising

their cattle in that

region by

the second or third

century

A.D.

is now a well established fact. In

fact, authoritatively

dated archaeo-

logical

sites from Zambia and Rhodesia show the

presence

of settled

communities of Iron

Age peoples

between A.D. 185 and A.D. 300.18 These

were

village

dwellers who were

experimenting

with iron

smelting

and

pottery making.

We also know that in Zambia trade items from the coast

are

quite

common in

archaeological

sites

dating

from the sixth or seventh

centuries.19 These sites are also rich in

pottery

and carved stone

items, indicating

that the bowls of

pipes

essential in the

smoking

of

cannibis could have been

readily prepared

from either of these materials.

Further south

smoking pipes

were found in the

Brandberg,

South West

Africa,

where

they

were associated with

large, open-station

settlement

sites attributed to the

Bergdama.

Two of these sites have radiocarbon

dates of 1590 and 1730 A.D. respectively.20 Apparently then people here-

abouts were

smoking by

the sixteenth

century.

Based on ethnohistorical

information we would

suggest

that

they

were in fact

smoking

cannabis.

If we look to the north of the

general region just discussed,

it

is clear that cannabis was

being

used in the northern

Kenya-southern

Ethiopia region shortly

after the thirteenth

century

date

suggested

for

the introduction of cannabis into Africa. That it was

being

smoked is

borne out

by

excavations in

Ethiopia

where two ceramic

smoking-pipe

bowls

were excavated with a date determined to be

1320+80

A.D. More

important

however is the fact that both

yielded positive

tests for cannabis-

derived

compounds.21

ETHNOGRAPHIC EVIDENCE

A

survey

of seventeenth

century

and

eighteenth century

travel docu-

ments, ethnographies,

and

anthropological

studies

presents

a

picture

of

established cannabis users

throughout

sub-Saharan Africa.22 This

applies

not

only

to the Khoikhoi herders in the south and their San

neighbors

but also to the

Bantu-speakers

in contact with them. It

applies equally

to most of the

Negroid peoples

in

south, east,

and central Africa. This

common cultural

pattern

of use and the terms used to refer to the herb

(see below) suggests

a

longstanding acceptance

of cannabis in most of

sub-Saharan Africa.

There is

by

contrast a

significant

absence of cannabis

among

the

traditional societies in West Africa. We do know that

early

north-

south trade routes existed across the Sahara and that a

degree

of trade

This content downloaded from 71.172.230.211 on Thu, 22 Aug 2013 17:40:27 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

20

existed centuries before

Europeans

made their contacts from the sea.

This

point

must be

emphasized

because cannabis has

always spread

due to

the contact of

peoples

and the trade route would thus be a normal mode

of diffusion. We also know that cannabis was

present

in

Egypt

at about

the same time that it was introduced to the African east coast.

However,

although

the herb was used

extensively

in

Egypt

where it was

grown

in

gardens

and

traded--ultimately

as far west as

Spain--during

the fourteenth

century,

it failed to

spread along

the trade routes across the Sahara.

This hiatus

might

be

explained

in terms of a desert climate which was

not conducive to its

growth

or an

unwillingness

on the

part

of desert

people

and West African

Negroes

to

accept

it. It is also

possible

that

it was not

acceptable

while in the form of dried leaves. We

know,

for

example,

that

throughout

this

period cannabis,

under the name "hashish"

was eaten in

Egypt

and

only

much later used in

pipes.

Thus it

might

not

have been

accepted

because it was not

integrated

with an established

cultural

pattern.

Whatever the reason we have found no evidence of can-

nabis in West Africa before the Second World War.

It is

possible,

of

course,

that the West African

peoples

were

simp-

ly

not interested in the

herb,

that the

population

movements were east

and

south,

thus

discouraging

much diffusion or elaborate trade routes

westward,

or that a combination of

geographical

barriers and

ecological

zones

discouraged

its

spread.

It is more than

likely

that a combination

of these various factors was-involved.

West Africa's isolation in this

regard

was breached when its

people

went eastward to war. As T. Asuni

points

out: "Cannabis sativa is not

indigenous

to

Nigeria,

and evidence indicated that it was introduced to

the

country

and most

likely

to other

parts

of West

Africa, during

and

after the second World War

by

soldiers

returning

from the Middle East

and the Far

East,

and North

Africa,

and also

by

sailors."23 There is

furthermore no traditional name for it

though

a number of local refer-

rents have since

emerged. Although by

1965

Nigeria

was a

supplier

for

local

consumption,

as well as for "illicit traffic between

neighboring

countries and in international illicit

traffic,"24

researchers have found

the herb to be used

primarily by "marginal" Africans; by young migrant

workers; by "organized political thugs;"

or

by "recently

evolved secret

societies with criminal

aims,

such as Odozi Obodo and the

Leopard-men

society

of

Nigeria"25 apparently

used as a

compensatory drug

under stress.

In contrast to some of the cases in East Africa where cannabis is well-

accepted

and used

by

males and females

alike,

in

Nigeria

we find that

it is "almost

entirely

confined to the male sex."26

Further

west,

in

Ghana,

the situation is almost identical to that

in

Nigeria.

The first

illegal

cultivation of cannabis in Ghana was

reported by police

in 1960 where the herb is called

"Wee,"

which is seen

by

one author as "a

corruption

of 'weed'

by

seamen."27 It is

smoked,

but

only

in the form of a rolled

cigarette.

We can thus view it as a

truly

recent introduction without the normal

accompanying paraphernalia

of the

waterpipe.

This content downloaded from 71.172.230.211 on Thu, 22 Aug 2013 17:40:27 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

21

THE LINGUISTIC PICTURE

There are two

important

terms in the

history

of the herb: Sanskrit

bhanga

which resulted in the Hindi use of

bhang;

and Arabic

kinnab,

a

word which

probably

accounted for the

adoption by

Linnaeus the botanist

of the sub-order cannabis.

In its natural form in

India, growing

either wild or in a cultivated

state,

cannabis was referred to as

bhang.

This term

applied

to the

dry

28

leaves of the

hemp plant

which were used either for a tea or for

smoking.

It is also the word which

spread

with the herb itself.

Early

Muslim

writings,

from the thirteenth

century onwards,

refer

to

banj

or hashish29 but the former

may

in some cases have referred to

henbane. Those

early

writers who criticized the use of the herb as a

drug, however,

did use

banj

for cannabis. Medieval Muslim

society

also

recognized

its use and

distinguished

it from all other medicinal herbs.

The use of

hashish,

which could refer to

grass

as

fodder, weeds,

medici-

nal herbs and so forth was

simply

a nickname and could be an abbreviation

of al-hashish al-muskir "the

intoxicating

hashish."

The early

Arab traders introduced the term

bang

to Africa and in

linguistic

variant

forms,

it is found all over east and south Africa.

Thus the Dictionnaire Swahili

-

Fransais

prepared by

the Institut d'Eth-

nologie (Paris, 1939)

refers to

Bangi,

which indicates Indian

hemp

or

hemp-like

dried

top

sections

prepared

as intoxicants. The

origins

of the term are listed as: Hindi:

bang,

Arabic:

banj,

and Persian bandz

(banj).

In the

region

of the East African Great

Lakes, just

south of Lake

Victoria, cannabis is referred to as bhangi30--no

doubt the result of

early

Swahili contacts. When the

explorer Speke during

the

1850's

made

his

way

from the coast to the Great Lakes he found Arab communities and

cannabis in use. The use of

banghi

was common as it still is

among

the

Swahili

along

the coast.

Variations of

bangi are, however,

found further south. Thus the

Thonga31

in the Zambezi

valley

refer to cannabis as

mbange,

while the

Rhodesian Shona use

mbanji.

Just south of the

Limpopo

divide, south-

west of the

Thonga,

live the Venda who refer to it as

mbanzhe,

and the

Sotho

speakers

called it lebake or

patse.

A

slight phonemic

variation

occurs

among

the Swazi-Zulu

speakers

who use the term

ntsangu

and the

Lamba in the

present

Zambia have

long

used

uluwangula.32

Referring

to

a much more recent situation in

Rwanda,

Helen Codere-

reports

on canna-

bis use

among

the

indigenous population. Cannabis,

"called

injaga

in

Kingarawanda,"

is associated with the Twa of both sexes and

only very

rarelK

with Hutu and Tutsi. The

latter, however,

use the herb medicin-

ally.34

We find then a

geographical complex along

the east coast and extend-

ing

some hundreds of miles

inland,

or

along

the

Zambezi,

where

indigenous

Bantu

speakers adopted

not

only

the herb but also the term

bang.

The

presence

of Arab traders

among

them

probably

had some influence in this

regard

but the

early

dates for

smoking pipes suggest

that cannabis

may

have

preceded

its Arab bearers in the

process

of diffusion.

Bang

and its Bantu derivatives are not found in all of southern

Africa. In the southernmost

part

of the continent we encounter an

historical accident which resulted in a common nomenclature which

This content downloaded from 71.172.230.211 on Thu, 22 Aug 2013 17:40:27 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

22

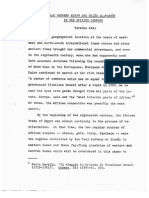

E l-ang-

l

dagga

-lomajor

diffusion route

-~- minor diffusion route

This content downloaded from 71.172.230.211 on Thu, 22 Aug 2013 17:40:27 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

23

clouds the

geographical

and historical

importance

of this

single

term.

This is due in

part

to an erroneous

application

of the term and to

gen-

eralization which followed.

The earliest use of the term

"dagga"

of which we are aware occurs

in the

diary

of Jan van

Riebeeck,

the first

governor

of the new Dutch

settlement at the

Cape

of Good

Hope.

The date was

1658,

and it was

spelled

as

"daccha."

It is almost certain that here and in numerous

subsequent

references we are not

dealing

with Cannabis sativa but with

Leonotis leonurus a well-known

flowering

shrub used

by

the Khoikhoi.

Van Reibeeck refers to this daccha as "een

droogh cruyt

dat de Hottentoos

eeten ende droncken van worden"

(a dry powder

which the Hottentots eat

and which makes them

drunk).

In

discussing

the medicinal and

poisonous

plants

of southern

Africa,

J. M. Watt and M. G.

Breyer-Brandwijk point

out that Leonotis leonurus R.

Br.,

also referred to as Rooi

dagga,

Wilde

dagga,

or

Klipdagga

was in

early

times smoked

by

the Khoikhoi instead of

tobacco.

They

also

quote early

authors to the effect that the White

Colonists

employed

the

plant

and that "the

preparation produces

narcotic

effects if used

incautiously,"35

and that "Laidler records that in olden

times the Namas formed the

powdered

leaf into cakes which were chewed

evidently

for the

intoxicating

effects."36

Many

of the same

properties

are ascribed to another member of the

family,

Leonotis leonotis R.

Br.,

also referred to as

Knoppies

dagga

or

Klipdagga.

While it is

impossible

to confuse the adult

plant

of Cannabis sativa

and adult

specimens

of the Leonotis

group

which bear clusters of

bright

red

flowers,

it is

likely

that the common use and related effects of

these two

plants

lead to the similar term

being applied

to both

plants.

This

classificatory

error also underlies

suggestions

that Cannabis

pro-

ducts were eaten or drunk in the

Cape.

As well as

being eaten,

the

Leonotis leaves were also

smoked, usually

after

being

mixed with

tobacco,

so that a double confusion arose in

contemporary writings.

One of the most

complete linguistic analyses

of the term

"dagga"

37

has been made

by

G. S. Nienaber in his

study

entitled "Hottentots"

(1963).

In

suggesting two possible origins

for this term he refers to the works

of a number of

previous

researchers:

(a) Following

Hahn and Lichten-

stein,

it is

possible

that Dutch term tabak

(tobacco),

which

frequently

appears

as

twak,

was

corrupted

to

twaga,

later

toaga

and

finally dagga.

This however seems a farfetched

origin. (b)

A much more

plausible

postulate

is that the Khoikhoi term daXa-b or

baXa-b,

which

among

other

things

refers to

tobacco,

is the root noun from which

dagga

could be

derived. When

referring specifically

to

dagga

we find the

qualifier

!am

-

(green) being

added to the root mentioned

above,

and the result

is !amaXa-b

namely "green

tobacco" or

dagga.

Lichtenstein, Meinhof,

and Nienaber himself doubt that

dagga

is an

original

Khoikhoi word. Meinhof

goes

so far as to

suggest

that

dagga

is

really

a derivative of the Arabic word duXan

(actually

duXXan or

tobacco,"38

which came in

by way

of the

early

Khoikhoi

migrants.19

We

should

immediately point

out that no other

language group

in South Africa

ever used such a term or

anything resembling

it.

Early European

observers in South Africa

normally

had

difficulty

in

recording phonetically

the terms

they

heard

among indigenous peoples.

In time a

variety

of

spellings

for this common Khoikhoi word

began

to

appear

in the literature. Thus we find daccha

(1658),

dacha

(1660),

This content downloaded from 71.172.230.211 on Thu, 22 Aug 2013 17:40:27 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

24

dackae

(1663), dagha (1686), daggha (1695), dagga (1708), tagga (1725),

dacka

(1775),

and

daga

(1779),

as writers recorded the

practices

asso-

ciated with the

plant.40

We must

repeat

that not all these writers in

fact were

referring

to Cannabis sativa.

Furthermore,

not all of them

were

speaking

of

smoking

the herb to which

they

referred.

Since

early

white settlers were introduced to cannabis in southern

Africa

by way

of the Khoikhoi

herders,

it was

only

natural that the

term

dagga

became the common referrent.

Today

it is the standard term

in formal

English

and Afrikaans

references, social,

medical and

legal.

We thus far have established two

terminological complexes

in

Africa,

namely,

terms derived from the Hindi term

bang,

and the

widely

used but

narrowly

distributed term of

dagga.

There

is, however,

a third terminolo-

gical complex

which extends over a

relatively

wide

region covering

Angola

and Zaire. Here we find the terms

diamba, riamba, liamba,

or

chamba. When it was discovered that cannabis

in Brazil was known

by

these terms it was

thought

that these words had

perforce

to be of Portu-

guese origin.

It was furthermore

argued

that either the herb had

reached the African south-west coast

by

the time slaves were taken to

the new world or that the

Portuguese

were instrumental in the diffusion

of the term--and

possibly

the

plant.

One of the most

interesting

areas from which our

analysis may begin

is the

Congo drainage

area and its border districts. From

ethnographic

sources we know that cannabis was used in

present day Zaire,

where for

example hemp-smoking

was said to be "the curse of the Batetela in Kasai

province.'41

Harry

Johnston summarized the situation

by stating

that

"hemp

as a narcotic is not much used in the

Congo

basin

except

in the

southern, south-western,

and south-central

parts,

and the western

Mubangi.

This

practice

has

nearly

died out in the

Kingdom

of

Kongo,

though

it was

prevalent

once. Of late

years hemp-smoking

has

developed

in a rather sensational fashion

among

the excitable

Bashilange..."42

The latter is a

sub-group

of the

larger

Luba

people

and

occupy

the

area around the confluence of the Lulua and the Kasai. It would

appear

that Swahili traders from Zanzibar43 introduced Cannabis into the

region

after the 1850's and the

original "bhang"

was here referred to as "riamba."

During

the civil strife in the

early

1870's a secret

society calling

itself Bena-Riamba was formed.

Early

writers translated this as "Sons"

of

hemp,

but Johnston

pointed

out that we should differentiate bena

(meaning "brothers")

from bana

(meaning "children").

He

suggested

the

use of an initial D- rather than R-44 to read Bena-Diamba. Because

the use of riamba is

ubiquitious

we will retain it in this discussion.

In time there was concern about the

increasing

use of the herb in the

Congo region

and secret societies were formed to counter its use. A

quarter

of a

century

after Johnston's remarks H. Wissman

pointed

out

45

that

"among

the

younger generation

it is

already beginning

to decrease."

It is

interesting

that

among

the

Badjok,

a southern Bantu

people,

who

reside in the same

region reported

on

by

Johnston and Wissman a research-

er met informants who "denied ever

smoking hemp,

but a

great quantity

of

it

grew

near

Mayila's hut--probably

as an ornament."46

47

Cannabis was also smoked in the northern

part

of Zaire and had

spread

into the former French

Congo.

A. L. Cureau stated that

people

smoke tocacco

moderately,

but "the same cannot be said for Indian

hemp,

the habit of

indulging

in which is

making frightful progress"'(sic )48

49

even

using

what was then

recognized

as a

"peculiar pipe

for

smoking

it."

This content downloaded from 71.172.230.211 on Thu, 22 Aug 2013 17:40:27 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

25

Northeast of the area

just

discussed

namely

in the Great Lakes

region,

around

Ujiji,

Richard Burton discovered that almost

every one,

"even when on board the

canoe,

smokes

bhang",50

but it was not as common

in the Lower

Congo. Writing slightly

later than

Burton,

Herbert Ward51

tells us that "wild

hemp smoking (Liamba)

is

practiced by

some of the

natives...The

practice

however is not

extensive,

and it would

appear

to

be a habit of

comparatively

recent

origin."

The

picture

which

emerges

is one in which cannabis was used

widely

but not

necessarily by

all

ethnic-linguistic groups.

We

do, however,

find a common term

through-

out the

Congo drainage region. According

to Jose Pedro Machado's

Dicionario

Etimologico

da

Lingua Portuguesa52

the words diamba and

liamba are derivatives of the Kimbundu word riamba which refers to the

cannabis

plant.

Also in

TchiLuba

the herb is referred to as diamba

and,

we are

told,

but need to

confirm,

that it is known in

KiKongo

as

mfanga.

We find the same noun-stem

being

used in the southern and eastern

part

of

Angola among

the

Vangangella53

and the Ovimbundu. The latter in fact

refer to cannabis as

epangue

and it is cultivated and smoked

exclusively

by

men.54

We are thus left with the

major terminological

divisions of an

-ang-

complex

derived from the term which was

originally

introduced and an -amb-

complex

said to be of Mbundu

origin.

It is

significant though

that

neither J. Gossweiler and F. A.

Mendonca

in their

highly regarded

Carta

Fitogeografica

de

Angola (1939)55

nor Do

Espirito

Santo in Nomes Vernac-

ulos de

Algumas plantas

da Guine'

Portuguesa (1963)56

refer to cannabis

in these

territories,

either

by

botanical classification or

by

the more

general

term. We

might suggest oversight

on their

part

or failure to

recognize

the

presence

of the

plant. (This

would not be an out-of-the-

way explanation,

for in a volume entitled Harvest of Time

-

Angola

of the

Past the

author,

Jose Maria d'Eca de

Queiros,

uses a

photograph

of him-

self57

smoking

a cannabis water

pipe apparently

without

being

aware of

the content since the

caption

reads: "After

choking

several

times,

the

author at last learns to smoke the water

pipe

of the

Quicos."

The

Ango-

lan onlookers were

obviously enjoying

the

experiment.)

What we would

suggest

is that cannabis

might

be of

fairly

recent

origin

so that it

is still seen as a

foreign

herb and not one of the "native"

plants

of

Angola

or Guinea.

CURRENT DIFFUSION HYPOTHESES

The literature contains a number of

suggestions

on the

spread

of

cannabis into southern Africa:

(1)

J. M.

Watt,

a

pharmacist,

has

suggested

that: "the

plant may

have

been introduced

by

the

early

travellers

circumventing

the

Cape

from the

east."58 Almost all our historical documentation and linguistic

evidence

suggests

a date

long

before the fifteenth or sixteenth

century

return of

European navigators.

(2)

Theodore

James, basing

his

argument

on a

single

case of termino-

logical agreement (namely

Hindi and

Shangaan /Thongaj

-

already

men-

tioned)

states that: "the

plant

was first carried to the coast of

59

Mozambique...by

the

Portuguese

militant traders

returning

from

India."

This sets the date even

later,

and

certainly

does not

recognize

documents

regarding early

use.

This content downloaded from 71.172.230.211 on Thu, 22 Aug 2013 17:40:27 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

26

(3)

J. E.

Morley

and A. D.

Bensusan, point

out that the

plant

is not

indigenous

to Southern Africa. "It

appears

most

likely

that it was

brought by

Arab traders to the

Mozambique

coast from India. From there

it was carried southwards

by

the

migrating

Hottentots and Bantu."60 In

general,

this

position

is

supported by

A. J. H. Goodwin.61 While rec-

ognizing

an earlier date of introduction of

cannabis,

this

hypothesis

is

rather

vague

as to "Hottentots and Bantu."

(4)

James Walton refers to his own

survey

of

archaeological reports

which refers to

pipes

found in

early

Bantu

settlements,

and also to Dos

Santos'

description

of cannabis cultivation

by

the eastern Shona in the

sixteenth

century.

He then

suggests

that cannabis "was introduced into

southern Africa

by

the

very

first waves of Bantu invaders from the

North."62 The use of the herb would then have

spread

from Bantu to

Khoikhoi and San. Walton's

suggestion certainly

comes closest to the

accumulated evidence

being presented

in this

paper.

(5)

There is one additional route we must

keep

in

mind, although

this

has not been

incorporated

in

any

of the diffusion

hypotheses:

a

spread

from south Arabia

through Ethiopia.

It is well established that the

Amhara

people very early

on came from

Arabia,

but a

variety

of

products

preceded

and followed this Semitic invasion. Thus Simoons

suggests

that contacts between ancient Cushitic

peoples

and settlements north of

the Red Sea were continued in later times when Amhara settlers continued

these contacts.63 In the

process, plough agriculture,

a zebu strain of

cattle,

and various

agricultural products spread

to

Ethiopia.

The

question

which arises is whether cannabis could have been one of these

products. Recently

N. J. van der Merwe

reported

on two ceramic

pipe

bowls excavated at Lalibela cave near Lake Tana. Both were

parts

of

water-pipes

and had been

impregnated

with definite cannabis-derived

compounds.

The author concluded that "some

variety

of Cannabis sativa

was smoked around Lake Tana in the 13th-14th

century,

in much the same

way

as it is

today."64

The

importance

of the Lake Tana find and the associated radiocarbon

dates are of

great significance. They imply

either that cannabis entered

Ethiopia

from southern

Arabia,

or that it

spread

from the east African

coast in a

northerly

direction from

Bantu-speaking

to Cushitic

peoples.

One

problem

which arises is that Lake Tana is in the north central

part

of

Ethiopia.

Could we

postulate

a trade route from the

present-day

Kenya

into northern

Ethiopia? Unfortunately

we have not

yet

come across

a

thorough study

of

early

trade routes in northeast Africa and are thus

not able to

suggest

diffusion from the

Kenya

coastal

region

to Lake

Tana. Such diffusion

may

in fact have occurred

prior

to the east Africa

settlement of the Arabs.

However,

if we are

dealing

with a

spread

of cannabis from the north

into

Ethiopia,

and Franz Rosenthal

suggests

that "the use of hashish

spread through India,

China and

Ethiopia...,"65

there remains one cri-

tical issue

involving

the

way

it was used.

Referring

to the use of

hashish in medieval Muslim

society

Rosenthal also notes

emphatically

66

that "in our

sources,

hashish is never described as

having

been smoked."

Since the estimated date for the Lake Tana excavation is no more than

a

century

later than most of the other references used

by

Rosenthal we

are

dealing

either with a

very rapid change

in method of

use,

or with

an

independent

diffusion not

typical

of the other methods used around

the

region.

This content downloaded from 71.172.230.211 on Thu, 22 Aug 2013 17:40:27 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

27

The available evidence then seems to allow for a

possible

diffusion

of cannabis from

Syria

to

Ethiopia.

Diverse sources of evidence

suggest

Khoikhoi contact,

for instance in the

presence

of

pottery, cattle,

and

words. Merrick

Posnansky points

out that "evidence of a trickle of

peoples

from the Horn in the last millennium of the

pre-Christian

era

and in the first of the

post-Christian

era is available from the

Eryth-

riote (or caucasoid)

skeletal remains from the

Horn, Kenya,

Tanzania

and Malawi."67 The first contacts with Khoikhoi found them to

possess

"a form of zebu cow which

probably accompanied

them sometime in the

first half of the

present

millenium if

pottery parallels

between East

Africa and South Africa are

any

indication of a fold movement." We

have

already

mentioned the Khoikhoi word for tobacco. If the

argument

outlined here is considered

seriously

it would

imply

that Khoikhoi had

close contact with

Ethiopia

and then

spread

south

along

the east coast

prior

to the Bantu

expansion.

As the Bantu

occupied

the coastal

region

and

migrated southward, they

forced the Khoikhoi into a similar

migra-

tion which

finally brought

them to the

Cape.

An alternative

explanation,

of

course,

is that cannabis and the

water

pipe

diffused from East Africa. This would

certainly

tie in with

the rest of the data

presented

here. It also rests

very heavily

on a

dispersal

from the south into

Ethiopia along

trade routes described for

a later

period by

Richard Pankhurst.68

Just as

likely

an

hypothesis

is one which

postulates

the

spread

of

cannabis from earlier Arab settlements or Indian trade centers around

the Horn of Africa. Diffusion would then have been effected

along

the

salt-trade routes discussed

by

Abir.69 This would even allow for the

spread

of cannabis

directly

from

India,

since it is

recognized

that in

the tenth

century

"Indian merchants were

visiting

Sokotra in vessels

70

called

baraja,

and

/that/ they

were often in conflict with the Muslims."

If we were to

accept

the Horn of Africa as a diffusion center it

would

imply

either that these Indian traders used the water

pipe

and

introduced it

along

with

cannabis,

or that

they

learned about the water

pipe

from Arab traders

during

these

excursions, or, finally,

that the

water

pipe

was

independently

invented near Lake

Tana,

a somewhat

unlikely

conclusion in the

light

of the

subsequent

diffusion of the water

pipe.

Though

he was not concerned in detail with the diffusion of canna-

bis,

A. H.

Dunhill, writing

for the

Encyclopaedia

Britannica, apparently

has his

chronology

and his

migration

routes backwards. He states:71

"The Bushmen and Hottentots of southern Africa used the dakka

pipe;

which cooled and

mitigated

the effects of

hemp

smoke

by drawing

it

through

a horn of water.72 While Africa continued to

produce

more

orthodox

pipes

of almost

every possible

material and size the water

pipe spread

to India... and the Far

East, and...was

popular...in

Persia

in the 17th

Century."

Most scholars

eg.

Laufer73

recognized

the water-

pipe

as

originating

in Persia and

spreading

south and east from there.

We should once

again point

to the

significance

of van der Merwe's

statement

(vide supra)

that the two 13th

century

ceramic

pipe

bowls

excavated in

Ethiopia

"formed

part

of

waterpipes."74

We are aware of course that the water

pipe

did not

require

the

elaborate

parphernalia

now associated with it. In Africa a wealth of

forms

appeared,

as

gourds, antelope horns,

and other containers were

adopted.

In modern urban

settings everything

from milk bottles and soft

This content downloaded from 71.172.230.211 on Thu, 22 Aug 2013 17:40:27 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

28

drink cans to coconut shells are used as water containers. In this

respect

it is of interest that the

waterpipe

which was

integrated

into

Indian

hemp smoking

came to be called the

Nargila,

derived from

Nargil,

the word for a

coconut,

and based on Sanskrit narikera

meaning

coconut.

CONCLUSION

In the

light

of all the evidence available to

date,

none of which

is either conclusive or

quite satisfactory,

we should like to offer the

following hypothesis regarding

the diffusion routes of cannabis in

major

outline

only

in sub-Saharan Africa. We

have,

for reasons cited

above,

presumed

that the

Khoikhoi,

who

preceded

the later

Negroid migrants

southward across the African

plateau

and

along

the east

coast,

were not

the

major

bearers of cannabis.

During

the first

centuries

A.D. Arab traders who had settled around

the Horn and southwards from

Mogadishu

had introduced cannabis to the

indigenous

African

population.

It would

appear

that the herb was intro-

duced as a

product

to smoke rather than in the form of hashish to be

eaten as it was in

Egypt.

From these northern locations

along

the coas-

tal settlements of what is

today

Somalia and

Kenya,

cannabis was carried

and traded into the interior where its

presence

and use in northwestern

Ethiopia

have been documented.

At about the same time Bantu

speakers

were

living

not

only

on the

east African

plateau

but also

occupied

"in force the humid coastal belt"

as far north as the Juba.75 This is

just

south of the

city

of

Mogadishu

in the

general

area of the earliest settlements referred to above. The

Arab settlements

during

this

period

which are best

documented, however,

were further south on Pemba and

Zanzibar,

and also on the mainland as

far south as Kilwa. From here Swahili

(and Arab)

traders introduced the

herb to Bantu settlers. The latter were

mostly

Iron

Age peoples

who

were

expanding

their

population

and

incorporating

new

territory,

inclu-

ding

most of the drier inland areas of

Kenya

and Tanzania and no doubt

northern Zambia and

Katanga (Shaba).

The herb needed no advocate. It

is after all a "social"

plant, basically

associated with human settle-

ments and

given

the warm climate of central Africa it was

capable

of

spreading quite readily.

It would seem

logical

that with the

early

contact and trade

by

Africans from

Angola

cannabis

might

have reached the

Kongo

and Mbundu

by

the

early part

of the sixteenth

century.

This was a

period

of inten-

sive interaction

during

which slaves were traded and

political

alliances

formed. In his discussion of valued items traded

by

the

Kongo, Mbundu,

and

Ndongo,

David

Birmingham76

does not mention cannabis or

anything

related to

it,

but he does show the kind of networks which extended from

the west coast to

peoples

in the interior. The

Portuguese

traders first

moved

up

the Kwanza and contacted the Mbundu.

They

also traded slaves

from the

Kongo,

and these two

groups (the

Mbundu and the

Kongo)

were in

contact with the Lunda and the Luba further east. It was

here,

we

would

suggest,

that cannabis was used in the form of

mfanga

and where

the

phonemic change

occurred so that it was referred to as riamba. This

was also the word

accepted by

the

Portuguese

and

exported

to Brazil with

the slaves.

This content downloaded from 71.172.230.211 on Thu, 22 Aug 2013 17:40:27 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

29

At the same time that cannabis was carried into the interior of

Africa,

Arab traders settled further

south,

and then moved

up

the Zam-

besi River in order to trade with the Rozwi

Empire.

Brian

Fagan

and

D. W.

Phillipson77

refer to a

pipe

"with a male stem" which was un-

earthed at Sebanzi in Zambia.

They

date it as

coming

"from the level

dated cir. A.D.

1200."

In a

personal

communication

Joseph Vogel,

who

is

currently conducting

research in the

area,

informs us that he tends

to treat "the Sebanzi conclusions as

interesting,

worth

investigating

more

fully,

but

necessarily

tentative." It still leaves

us, however,

with an

early

date for the

presence

of a

smoking pipe.78

The Zimbabwe

complex may

offer more

convincing

evidence. Within

an

archaeological

stratum which reached its climax about 1450

A.D.,

Summers found "some

pipes

for

smoking dagga (Indian hemp)."79

He

neither indicates the

depth

of the

particular

find in terms of the

level,

nor whether the ash in the

pipes

was tested for cannabis deriva-

tives. We are thus left with

archaeological

evidence of

smoking pipes

and cannabis in southern Africa no later than the middle of the 15th

century,

and

possibly

earlier.

The

hypothesis regarding

this diffusion would then allow for the

spread

of cannabis from Rhodesia southward or westward into and across

the Kalahari. It would seem

likely

that the

Bergdama by

this date were

already growing

the herb which

they

had received from earlier Khoikhoi

or from their

neighbors

to the

north,

the Ovambo and

Ovimbundu, repre-

senting

the furthest known

spread

westward of the

linguistic

stem

-ang-.

The Ovimbundu refer to

epangue,

a term

very

close to the Ovambo

epangwe.

The

Bergdama speak

of daXab

suggesting

that

they

obtained

knowledge

about

the herb from

Nama-speakers prior

to contact with the Orambo.

While the herb was never of

major

economic

significance throughout

most of Africa it was

recognized

as

having

a

strong

traditional value

and therefore formed

part

of the trade

goods

of

many peoples.

The

hypo-

thesis which has been

presented

in this

paper pointed

at a number of

areas in which more information is needed. The

linguistic picture

is

perhaps

the most

complete.80

Much of the historical and

archaeological

evidence

may

have been clouded

by acceptance

of the

argument

that

nothing

was smoked before the

Portuguese

introduced tobacco.

Currently

I am

involved in an extensive literature

survey

to trace all references to

cannabis use. Such research is

linking

historical information with the

modern situation. As its users

migrated

to urban

areas,

cannabis has

gained

in economic

importance

and

finally

its

illegal

status has

placed

an even

greater monetary

value on this ancient herb.

NOTES

The research on which this

paper

is based was

supported

in whole

by

P. H. S. Research Grant D.A. 00387 from the National Institute on

Drug

Abuse. Field work was conducted in southern Africa

during

1972-1974 and

the

analysis

of research data is now

being

concluded. While I

express

my

sincere

gratitude

for the financial

support,

the

findings

are not

necessarily

shared

by

the

granting agency

or

any person

associated with

it.

Appreciation

should also

go

to Drs.

Haig Der-Houssikian,

and David

Niddrie who commented on an earlier draft of this

paper.

This content downloaded from 71.172.230.211 on Thu, 22 Aug 2013 17:40:27 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

30

Richard E. Schultes, "Man and

Marijuana,"

Natural

History,

Vol.

LXXXII,

No.

7,

1973.

2Neville

Chittick,

"Kilwa and the Arab Settlement of the East African

Coast,"

Journal of African

History,

Vol.

IV,

No.

2,

1963.

3Neville

Chittick,

"The 'Shirazi' colonization of East

Africa,"

Journal

of African

History,

Vol.

VI,

No.

3,

1965.

4Franz

Rosenthal,

The

Herb,

Leiden: E. J.

Brill, 1971, p.

160.

5Ahmad M.

Khalifa,

"Traditional

patterns

of Hashish use in

Egypt,"

in

Vera Rubin

(ed.),

Cannabis and

Culture,

The

Hague:

Mouton Pub-

lishers, 1975, p.

199.

6A. Mc

Martin,

"The introduction of

sugarcane

to Africa and its

early

dispersal,"

The South African

Sugar

Year

Book, 1969-70, Durban,

1970, p. 16.

7See the excellent discussion in M. D. D.

Newitt, Portuguese

settlement

on the Zambezi, New York: Africana Publishing Co., 1973.

Brian

Fagan,

Southern

Africa,

New York: Frederick A.

Praeger,

1965.

9Chittick,

"'Shirazi' colonization," p.

271.

B. M. Fagan,

"Early trade and raw materials in South Central

Africa,"

Journal of African

History,

Vol.

X, 1969, p.

10.

lJ.

Vansina,

"Long-Distance trade routes in Central

Africa,"

Journal of

African

History,

Vol.

III,

1962.

12Jacques Nenquin, "Notes on some early pottery

cultures in northern

Katanga,"

Journal of African

History,

Vol.

IV,

No.

1,

1963, p.

236.

13N.

Sutherland-Harris, "Trade and the Rozwi

Mambo,"

in Richard

Gray

&

David

Birmingham (eds.),

Pre-Colonial African

Trade,

London: Oxford

University Press, 1970,

and S. S.

Dornan,

Pygmies

and Bushmen of the

Kalahari,

London:

Seeley,

Service & Co.

Ltd,

1925.

13aH.

Vedder, Quellen zur Geschichte von Siidwest

-

Afrika,

Vol. 2.

Type-

script

in State

Archives,

Windhoek.

14See

the discussion in Brian M. du

Toit, "Dagga

- the

history

and ethno-

graphic setting

of Cannabis sativa in southern

Africa,"

in Vera

Rubin

(ed.),

Cannabis and

Culture,

The

Hague:

Mouton

Publishers,

1975.

15Ibid.

This content downloaded from 71.172.230.211 on Thu, 22 Aug 2013 17:40:27 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

31

16Phillip V. Tobias, "Physique of a desert

folk,"

Natural

History,

Vol.

70, 1961,

p.

24.

17Dornan, "Pygmies... ," p.

122.

18R. R.

Inskeep,

"The

Archaeological Background,"

in Monica Wilson and

Leonard

Thompson (eds.),

The Oxford

History

of South

Africa,

New

York,

Oxford

University Press, 1969, p.

32.

19Fagan,

Southern

Africa, p.

93.

20Leon

Jacobsen, personal communication, September,

1975.

N. J.

Van der Merwe, "Cannabis Smoking

in

13th-14th Century Ethiopia:

Chemical

Evidence,"

in Vera Rubin

(ed.),

Cannabis and Culture. The

Hague: Mouton Publishers, 1975.

22du Toit, "Dagga..."

T. Asuni,

"Socio-psychiatric problems of cannabis in

Nigeria,"

Bulletin on

Narcotics,

Vol.

16,

1964.

A. Tella,

et. al., "Indian hemp smoking," Journal of Social Health in

Nigeria,

Vol.

40, 1967, p.

40.

T. A.

Lambo, "Medical and Social problems of

drug

addiction in west

Africa,"

Bulletin on

Narcotics,

Vol.

17, 1965, pp.

3 and 6.

A. Boroffka,

"Mental illness and Indian

hemp

in

Lagos,"

Bulletin on

Narcotics,

Vol.

18, 1966, p.

378.

E. C.

Sagoe,

"Narcotics control in

Ghana,"

Bulletin on

Narcotics,

Vol.

18, 1966, p.

8.

28Brian M. du

Toit,

"Historical and Cultural factors of

drug

use

among

Indians in South

Africa,"

Journal of

Psychedelic Drugs (in press).

29Rosenthal,

The

Herb, pp.

19-20.

P30aul Kollmann,

The Victoria

Nyanza,

London: Swam Sonnenschein,

1899.

31H.

A. Junod, The Life of a Southern African

Tribe,

New York: Univer-

sity Books,

1962

(originally published

in

1912).

32V.

Clement Doke, The Lambas of Northern

Rhodesia,

London:

George

G.

Harris,

1931.

33Helen

Codere,

"The Social and Cultural Context of Cannabis use in

Rwanda,"

in Vera Rubin

(ed.),Cannabis

and

Culture,

The

Hague:

Mouton

Publishers,

1975.

This content downloaded from 71.172.230.211 on Thu, 22 Aug 2013 17:40:27 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

32

34By deleting

the

typical

Bantu noun

prefixes

and

allowing

for some

pho-

netic

adaptation,

the reader will be able to see the noun-stem

-ang-

or

slight phonemic

variations on this form.

35J. M. Watt and M. G.

Breyer-Brandwijk,

The Medicinal and Poisonous

Plants of Southern

Africa, Edinburgh:

E. And S.

Livingstone, 1932,

p.

156.

36Ibid, p.

157.

37G. S.

Nienaber, Hottentots,

Pretoria: Van

Schaik, 1963, p.

157.

38Ibid, p.

243.

39See also in this

regard

the discussion under diffusion

hypothesis

no. 5 below.

40Vide

Nienaber, Hottentots, pp.

241-242 and R.

Raven-Hart,

Cape

Good

Hope

1652-1702: The First

Fifty

Years of Dutch Colonization as

seen

by

callers,

Vol.

1, Cape

Town:

Balkema, 1971, p.

507.

M. W.

Hilton-Simpson, Land and people of the

Kasai,

London: Con-

stable and Co.

Ltd., 1911, p.

156.

42Harry

H.

Johnston,

British Central

Africa,

London: Methuen & Co.,

1897,

pp.

607-608.

43A.

Keane, Man, past and present, Cambridge:

The

University Press,

1920, p.

114.

44Johnston,

British Central

Africa, p.

608.

45H.

Wissman,

My

second

journey through equatorial

Africa,

London:

Chatto

& Windus, 1891, p.

308.

46E.

Torday, On the trail of the

Bushongo,

London:

Seeley,

Service

6

Co., Ltd., 1925, p.

271.

47M.

R. P. Dorman, A Journal of a tour in the

Congo

Free

State,

London:

Kegan Paul, 1905, p.

88.

A. L.

Cureau, Savage man in central Africa: A

Study

of

primitive

races

in the French

Congo.

London: T. Fisher

Unavin, 1915, p.

229.

49Ibid., p.

238.

50Richard F.

Burton,

The Lake

Regions

of Central

Africa,

Vol.

II,

New

York: Horizon

Press, 1961, p.

70.

51Herbert

Ward,

A Voice from the

Congo,

London: William

Heinemann, 1910,

pp.

265-266.

This content downloaded from 71.172.230.211 on Thu, 22 Aug 2013 17:40:27 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

33

52Jose' Pedro Machado, Dicionario

Etimolo'gico

da

Lingua Portuguesa (2nd

Edition),

Vol.

II, Lisbon, 1967, p.

812.

53Childs

points

out that the Ovimbundu

recognize

a common

humanity

with

their southern and northern

neighbors

who are seen either as

"people"

or "comrades." "Similar

recognition

is not extended to the eastern

and south-eastern

neighbors

who are

lumped together

under the dero-

gatory

term

'va Ngangela'

or

ovingangela.

This eastern

region

as

far as the Great Lakes was the

happy hunting-ground

of the slave-

traders..." (G.

M.

Childs,

Umbundu

Kinship

and

Character,

London:

Oxford

University Press, 1949, p. 189).

54Wilfrid D.

Hambly,

The Ovimbundu of

Angola,

Field Museum of Natural

History,

Publication

329, Chicago, 1934, p.

152.

55

55. Gossweiler,

F. A.

Mendonga,

Carta

Fitogeografica

de

Angola,

Edicao,

Do

Gog'erno geral, Angola,

1939.

56J.

do Espirito

Santo,

Nomes Verna'culos de Algumas plantas da

Guin4

Portuguesa,

Lisbon:

Estudos,

Ensaios E. documentos No.

104,

1963.

57Jose

Maria

d'Eca

de

Queiros,

Seara dos

Tempos

-

Harvest of

time,

Lis-

bon:

Empresa

Nacional de Publicidade

(1969?), p.

290.

58J. M.

Watt, "Dagga

in South

Africa,"

Bulletin on

Narcotics,

Vol.

13,

1961, p.

9.

59Theodore James, "Dagga: A review of fact and

fancy,"

South African

Medical

Journal,

Vol.

44, 1970, p.

575.

60J. E.

Morley and A. D. Bensusan, "Dagga:

tribal uses and

customs,"

Medical

Proceedings,

Vol.

17, p.

409.

A. J. H.

Goodwin, "The origins of certain African food

plants,"

South

African Journal of

Science,

Vol.

36, 1939, p.

456.

62James

Walton,

"The

Dagga pipes

of Southern

Africa,"

Researches of the

National

Museum,

Vol.

1, 1963, p.

85.

63Frederick J.

Simoons,

"Some

questions

on the economic

prehistory

of

Ethiopia,"

Journal of African

History,

Vol.

VI, 1965, pp.

11-12.

64

van der

Merwe,

"Cannabis

Smoking...," p.

80.

65Rosenthal,

The

Herb, p.

45.

66Ibid, p.

65.

67Merrick

Posnansky,

"The

Origins

of

Agriculture

and Iron

working

in

Southern

Africa,"

in Merrick

Posnansky (ed.),

Prelude to East

African

History,

London: Oxford

University Press, 1966, p.

89.

This content downloaded from 71.172.230.211 on Thu, 22 Aug 2013 17:40:27 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

34

68Richard Pankhurst,

"The trade of Southern and Western

Ethiopia

and

the Indian Ocean Parts in the Nineteenth and

early

Twentieth

Centuries,"

Journal of

Ethiopian

Studies,

Vol.

III,

No.

2,

1965.

69M. Abir,

"Salt,Trade and Politics in

Ethiopia

in the

ZThmihai Mgsafent,"

Journal of

Ethiopian Studies,

Vol.

IV,

No.

2,

1966.

70

Richard

Pankhurst,

"The

'Banyan'

or Indian Presence at

Massawa,

the

Dahlak Islands and the Horn of

Africa,"

Journal of

Ethiopian

Studies,

Vol.

XII,

No.

1, 1974, p.

186.

71

A.

H.

Dunhill, "Pipe Smoking,"

Encyclopedia

Britannica, 1969, p.

1098.

72

In

this

regard

see also Brian M. du

Toit, "Continuity

and

Change

in

cannabis use

by

Africans in South

Africa,"

Journal of Asian and

African

Studies,

Vol.

XI,

Nos.

3-4, 1976,

and Brian M. du

Toit,

"Ethnicity

and

Patterning

in South African

drug use,"

Brian M.

du Toit

(ed.), Drugs, Rituals,

and Altered States of

Consciousness,

Rotterdam: A. A.

Balkema,

1976.

73Berthold

Laufer,

"The Introduction of Tobacco into

Africa,"

in B.

Laufer,

W. D.

Hambly,

and

Ralph Linton,

Tobacco and its Use in

Africa,

Field Museum of Natural

History, Chicago, 1930, p.

10.

74

van der

Merwe,

"Cannabis

Smoking...," p.

78.

75Roland

Oliver,

"The

problem

of the Bantu

expansion,"

in J. D.

Fage

and

R. A. Oliver

(eds.),

Paper

in African

Prehistory,

Cambridge,

the

University Press,

1970.

76David Birmingham,

Trade and Conflict in

Angola,

Oxford: Clarendon

Press,

1966.

77Brian M.

Fagan &

D. W.

Phillipson,

"Sebanzi: The Iron

Age Sequence

at

Lochinvar,

and the

Tonga,"

Journal of the

Royal

Anthropological

Institute,

Vol.

95,

Part

2, 1965, p.

261.

78Phillipson suggested that,

since these

pipes,

and

particularly

the

oldest bowl referred to in our

discussion, predated

1492 when

smok-

ing

tobacco was introduced to the Old World from the

New,

these

people

smoked some other form of tobacco or cannabis sativa.

(D.

W.

Phillipson, "Early Smoking Pipes

from Sebanzi

Hill, Zambia,"

Arnoldia,

Vol.

1,

No.

40, 1965, p.

2).

One

problem

with this

suggestion

is that these

pipe

bowls seem not to have been

parts

of

water

pipes.

79Roger Summers,

Ancient Ruins and vanished civilizations in southern

Africa, Cape

Town: T. V.

Bulpin, 1971, p.

164 and illustrated

p.

226.

This content downloaded from 71.172.230.211 on Thu, 22 Aug 2013 17:40:27 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

35

80We can reconstruct the diffusion of the term

bhang

in the

following

way.

It is

hoped

that

many

of the

questions

which still remain

will be answered as the research continues.

bh(ang)

b

(ang)hi

bh(ang)

i

Hindi

Swahili

Great Lakes

inj (ag )a

mf

(ang)

a

ep (ang)

ue

ep (ang)we

Rwanda

Kongo

Ovimbundu

Ovambo

mb

(ang)

e

uluw(ang)

ula

mb