Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Behind The 1940-41 Ban On The Khaksar Tehrik

Caricato da

Nasim Yousaf (Author & Researcher)0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

172 visualizzazioni6 pagineOn March 19, 1940, the Khaksar Tehrik (Movement) was banned by the Government of Punjab in British India, and Allama Mashriqi, his sons, and a very large number of Khaksars were imprisoned. In 1941, the Movement was banned on an all-India basis. Investigative research reveals that the ban on the Khaksar Tehrik and Mashriqi’s imprisonment were the result of mutual interest of the anti-Khaksar elements, including the British and the All-India Muslim League (AIML). Both saw Mashriqi and his Movement as a threat and sought to secure themselves. The following briefly sheds light on British and AIML motivations and the subsequent banning of the Khaksar Movement.

Titolo originale

Behind the 1940-41 Ban on the Khaksar Tehrik

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoOn March 19, 1940, the Khaksar Tehrik (Movement) was banned by the Government of Punjab in British India, and Allama Mashriqi, his sons, and a very large number of Khaksars were imprisoned. In 1941, the Movement was banned on an all-India basis. Investigative research reveals that the ban on the Khaksar Tehrik and Mashriqi’s imprisonment were the result of mutual interest of the anti-Khaksar elements, including the British and the All-India Muslim League (AIML). Both saw Mashriqi and his Movement as a threat and sought to secure themselves. The following briefly sheds light on British and AIML motivations and the subsequent banning of the Khaksar Movement.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

172 visualizzazioni6 pagineBehind The 1940-41 Ban On The Khaksar Tehrik

Caricato da

Nasim Yousaf (Author & Researcher)On March 19, 1940, the Khaksar Tehrik (Movement) was banned by the Government of Punjab in British India, and Allama Mashriqi, his sons, and a very large number of Khaksars were imprisoned. In 1941, the Movement was banned on an all-India basis. Investigative research reveals that the ban on the Khaksar Tehrik and Mashriqi’s imprisonment were the result of mutual interest of the anti-Khaksar elements, including the British and the All-India Muslim League (AIML). Both saw Mashriqi and his Movement as a threat and sought to secure themselves. The following briefly sheds light on British and AIML motivations and the subsequent banning of the Khaksar Movement.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Sei sulla pagina 1di 6

1

Behind the 1940-41 Ban on the Khaksar Tehrik

In Memory of the Khaksar Martyrs of March 19, 1940

Nasim Yousaf

Researcher & Author

On March 19, 1940, the Khaksar Tehrik (Movement) was banned by the Government of Punjab

in British India, and Allama Mashriqi, his sons, and a very large number of Khaksars were

imprisoned. In 1941, the Movement was banned on an all-India basis. Investigative research

reveals that the ban on the Khaksar Tehrik and Mashriqis imprisonment were the result of

mutual interest of the anti-Khaksar elements, including the British and the All-India Muslim

League (AIML). Both saw Mashriqi and his Movement as a threat and sought to secure

themselves. The following briefly sheds light on British and AIML motivations and the

subsequent banning of the Khaksar Movement.

British Alarmed by the Khaksar Tehrik

In the beginning of 1939, Allama Inayatullah Khan Al-Mashriqi (founder of the Khaksar Tehrik)

announced in Al-Islah (Khaksar weekly)

1

that, by 1940, the Tehrik would achieve its final

objective. In other words, Mashriqi would bring down the British rule in India and liberate his

nation. He also declared that if he failed, he would disband the Movement. To Mashriqi, ten

years (referring to the start of the Tehrik in 1930) was more than enough for any Movement to

accomplish its aim, or there would remain no justification to continue such an organization.

Towards the end of 1939, Mashriqi ordered the Khaksars to enroll an additional 2.5 million

members within the next six months, i.e. by J une 1940. This was the time when the Khaksar

Tehrik had already spread to every nook of India, and foreign branches had also been

established. Mashriqi was very close to his goal.

The Government agencies had been monitoring Khaksar activities, and its growth had become a

matter of concern for the British. This is evident from the Governor of Punjabs (Sir Henry

Duffield Craik) letter dated August 11, 1939 to the Viceroy of India (Lord Linlithgow): This

movement [Khaksar] is particularly prominentI have sent the Premier [Sir Sikander Hayat

Khan] a note on the subject. In another letter (dated September 13, 1939) to the Viceroy, the

Governor of Punjab considered the Tehrik to be the most troublesome. Further investigation of

Government of British Indias official documents uncovers that the Government considered the

Khaksar Movement to be threatening and most dangerous.

It is important to mention here that the Khaksar discipline, militant ability, and potential to bring

down British rule was actually revealed to the authorities during the Khaksar Tehrik and the

Government of United Provinces (U.P.)s conflict over the Sunni-Shia riots in Lucknow in 1939.

Inadvertently, this confrontation took place around the same time as the start of World War II

(WWII). The conflict resulted in the resignation of the Congress Ministry in U.P., and the

Provincial Government had to sign an agreement on November 04, 1939 with Khaksar leaders

on Khaksar terms to end the discord. This is evident from the Governor of U.P.s (Harry Graham

Haig) letter dated November 08, 1939 to the Viceroy of India:

2

The Khaksar problem was also a great embarrassment. I telegraphed to you on November 2nd

that the situation involved embarrassments and that I proposed to accept the resignation of the

Ministers next morning the Ministers felt their position and authority were being jeopardised

and questioned I had decided regretfully to accept the resignation of the Ministers We also

agreed to pay the fares of the men [Khaksars who had come to Lucknow from other provinces]

back to their homes. I should have preferred to omit both these terms, but it was clear that if we

wanted an immediate settlement we would have to accept something on these lines and I felt it

was better to settle at once than to run the risk of long discussions with a possibly doubtful

issue

2

Khaksar power can also be seen through the Viceroy of Indias secret letter (dated November 13,

1939) to the Governor of U.P, soon after the agreement between the two parties was reached.

Linlithgow wrote I confess that I should be greatly relieved, as I regard it [Khaksar Tehrik]

myself as having quite dangerous potentialities, to be free of it [Khaksar Tehrik].

3

This revelation of Khaksar power coupled with Mashriqis program made the British enormously

nervous. A few days (August 28, 1939) before WWII, J .C. Donaldson (Secretary to the Governor

of U.P.) wrote a secret letter to Sir J ohn Gilbert Laithwaite (Secretary to the Viceroy of India).

He stated that the Khaksar Tehrik has dangerous possibilities and that the Government is wary

of the Movement.

4

This changing dynamic in India tied with the onset of WWII in 1939 made the Government of

British India fearful of losing authority over the country. The Khaksar power and the war made

the British position extremely vulnerable. Thus, it was considered imminent to ban the Khaksar

Movement, and other prompt steps were also taken to eliminate this threat.

The Muslim League Leaderships Motivations

Mashriqis popularity and the Khaksar strength were also considered a threat to the growth and

political aims of the All-India Muslim Leagues leadership. Among the leaders, who felt

threatened and were hostile towards Mashriqi, were Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali J innah and

Premier of the Punjab, Sir Sikander Hayat Khan (member of the Working Committee of the

AIML).

J innahs hostility toward Mashriqi was indicative of his fear of being side-lined. The Viceroys

letter (dated March 16, 1940) to the Governor of North West Frontier Province (Sir George

Cunningham) explains what J innah thought of Mashriqi: in the course of our discussionI did

not get the impression that J innah himself had any very high opinion of Inayatullahs

balance On the same day, the Viceroy wrote a secret letter to the Governor of Punjab (Sir

Henry Duffield Craik); according to this letter, Quaid-e-Azam spoke ill of Mashriqi, referring to

him as rather crackbrained.

5

These letters were written only days before the ban was imposed

on the Khaksar Tehrik and atrocities were inflicted on the Khaksars and their leader. Quaid-e-

Azams mindset can be further understood via the Governor of Punjab, Sir Henry Duffield

Craiks, letter to Linlithgow (dated March 25, 1940). Craik wrote a gist of his conversation with

J innah, which he had had a few hours before the Pakistan Resolution was passed:

J innah then went on to speak of his interviews with Inayatullah [Allama Mashriqi] at Delhi and

admitted that he was hardly sane, extremely difficult to reason with and dangerously fanatical

He then went on to say that he hoped to be able to find sober and responsible men to assume

3

direction and control over it [Tehrik] Actually I [Governor] fancy he [J innah] visualises the

Khaksars as a potentially powerful propaganda agency on behalf of the Muslim League. He

[J innah] expressed the hope that if he was able to accomplish what he had in mind, my [Governor]

Ministry would agree to rescind their order declaring the Khaksars an unlawful association. At the

same time he admitted that the military side of the Khaksars activities, i.e., drilling, sham fights,

&c, was a menace to the public peace and could not be permitted.

6

By making such remarks, J innah paved the way to strengthen his own political position and

made a tactful attempt to side-line Mashriqi. Quaid-e-Azam sought to remove Mashriqi from

politics so as to remove a threat to his own political career. Moreover, he intended to bring the

Khaksar Tehrik under the Leagues flag to augment the Leagues position. In addition to the

letter above, the following offers proof in this regard. The Governor of North West Frontier

Provinces Report dated April 09, 1940 stated they [Muslim Leaguers] are attempting to bring

the organisation [Khaksar Tehrik] more under the discipline of the [Muslim] League.

7

It was not only Quaid-e-Azam who was against Mashriqi. Punjab Premier Sir Sikander Hayat

Khan also considered Mashriqi a direct threat to his political career in Punjab. He detested

Mashriqi and the Khaksar Tehriks popularity. Sir Sikanders enmity is visible from what the

Khaksar leader Raja Sher Zaman wrote in his book: Sir Sikander once said I will crush the

Khaksars within two days.

8

Sikanders hostility can also be gauged from the antagonistic

actions he took against Mashriqi and the Khaksar Tehrik on March 19, 1940 and thereafter.

The above offers proof that these leaders of the AIML were anti-Khaksars. It was in their vital

interest to eliminate Mashriqi, who was a threat to them, and also seek British blessings for

removing the Khaksar threat in the crucial time of WWII. Such circumstantial evidence

substantiated by historical documents speaks to the All-India Muslim Leagues behind the scenes

desire for the ban against the Khaksar Movement.

Towards Banning the Khaksar Tehrik

Quaid-e-Azam was not part of the Government, and Sir Sikander Hayat Khan was delegated the

authority to deal with the Khaksars. Sir Sikander was the right hand man of the British, as is

evident from the Viceroys letter to the Governor of Bombay, written four days after the ban on

March 23, 1940: Sir Sikander is one of the best people we have.

Soon after the green signal from the British, Sir Sikander started to prepare ground for imposing

the ban. Non-Khaksar newspapers were encouraged to print articles against the Movement, and

anti-Khaksar propaganda became a regular feature. An article even appeared in The Tribune

which tried to link the Khaksar Tehrik with the German Nazis. Furthermore, members were

prompted to raise questions in the Punjab Legislative Assembly about the activities of the

Khaksar Tehrik. Sir Sikander himself stated in the Assembly that the Khaksar Movement was a

communal Movement.

9

It was widely propagated that their activities were dangerous for peace

between Muslims and non-Muslims. The Movement was said to be communal, despite the fact

that the Tehrik was open to non-Muslims, and there were Hindus, Sikhs and others in the

Khaksar Tehrik. Anti-Khaksar elements were asked to issue anti-Khaksar press statements to

further create a justification for the ban.

The groundwork for imposing a ban on the Khaksar Tehrik was set. On February 22, 1940, a

police raid was ordered, Khaksar material was seized, and prohibition was imposed on the

4

publishing of Al-Islah. Soon after this police raid, Mashriqi sought J innahs help to resolve the

tangle with Sir Sikander. J innah did not come forward and instead said I wish Sikandar could be

my man. If it had been so I would have ordered him.

10

On March 19, 1940, 313 Khaksars marched in protest in Lahore against Government actions;

Punjab police, under the command of a British police officer, open-fired on unarmed Khaksars,

and a tragic massacre took place. On the day of this tragedy, the Khaksar Tehrik was banned in

Punjab, and Allama Mashriqi (who was in Delhi at the time), his sons, and a very large number

of Khaksars were imprisoned. A police raid was also held at the Khaksar headquarters in Lahore.

One of Mashriqis sons, Ehsanullah Khan Aslam, was injured during this police raid and later

succumbed to injuries and died on May 31, 1940. Mashriqi remained in jail for a long time; the

Government of British India failed to bring any charges against Mashriqi and he was kept behind

bars without a court trial. In 1941, the Movement was also banned on an all-India basis.

Quaid-e-Azam also promised to the public to help the Khaksars, and during the Muslim League

Session (March 22-24, 1940), he stated, I assure you and my friends of the Khaksar

organisation that we will not rest until we have got full justice

11

Regrettably, he did nothing

serious for the release of Mashriqi or the Khaksars. Moreover, to the Khaksar circle, Quaid-e-

Azam only appeared to be a supporter and well wisher of the Khaksar Tehrik in the public eye

and not behind the scenes. In addition, one must not forget that J innah never mobilized the public

or even visited Mashriqi in jail or his family, in order to avoid British resentment which might

have jeopardized his political career. Quaid-e-Azams luke-warm efforts were meant to

circumvent public pressure, rather than assist the Khaksars, and offer proof that he was in

support of the actions against the Khaksar Tehrik.

After the March 19

th

Khaksar massacre, ban on the Movement, and the arrest of Mashriqi and the

Khaksars, daily Khaksar protests and demonstrations against the ban began. Linlithgow gave top

priority to the matter and took personal interest to ensure that the Tehrik was completely

crushed; this is evident from his correspondence with Governors and Secretary of State for India

in London, including a secret letter (dated April 02, 1940) to the Governor of Punjab in which he

mentioned the situation in Lahore, the potentially dangerous character of the Khaksar Tehrik,

and that he wanted to address the overall matter as a priority.

12

It is important to note that desperate efforts were made to wipe out the Khaksar Movement, yet it

never died. In fact the more the Movement was suppressed, the more the demand for

independence, in light of the ban on the Tehrik and Mashriqi in jail, was heightened. The

political benefit of this was taken by AIML.

Vested Interests

The circumstances highlighted in this article shed light on the fact that the British and the

Muslim League leadership were among the leading proponents behind the ban on the Khaksar

Tehrik. Vested interests lay behind this move in the face of a powerful Movement that posed

a threat to British rule and the Muslim Leagues politics in India, both sought to secure their own

control.

By putting Mashriqi behind bars and banning the Movement, the British averted the downfall of

their rule in 1940. Instead they brought J innah to the frontline to start confrontational politics

5

with all parties (Muslims and non-Muslims). This gave a lifeline to the British to continue ruling

India, and they were able to maintain their stay until 1947.

Quaid-e-Azam too wanted to ban the Movement. His political position at the time had been very

weak, and the Khaksar Tehrik and Mashriqi were a direct threat. With Mashriqi in jail and the

Movement banned, J innah sought to capitalize on the wailing masses, bring the Khaksars under

the Muslim League flag, and emerge as the sole Muslim leader. With these circumstances and

support from the British, J innah did gain tremendously and emerged as a strong leader over time.

On the other hand, Sir Sikander, who had thought that by crushing the Khaksars he would secure

his political career in Punjab, in fact suffered heavily. After the Khaksar massacre, he lost his

popularity in the Muslim community, which J innah exploited to then secure his own power.

Mashraqi pointed out the role of the British and Quaid-e-Azam as well as the conspiracy against

the Khaksar Tehrik. His press release issued on August 26, 1943 stated:

19th [March, 1940] and the 26th J uly [1943, attack on Quaid-e-Azam] both were well planned

attacks on the Khaksar organisation, the one from the side of the Government and the other from

the side of Mr. J innah.

13

It is evident that the British and the All-India Muslim League were behind the ban on the

Khaksar Tehrik, for their own vested interests. Because the AIML played in the hands of the

British (as stated by Mashriqi and various nationalists) and because of the AIMLs wrong

policies, Muslims were weakened, deprived of their homeland, and left with a moth-eaten

Pakistan. The partition scheme resulted in the massacre of over one million people, the ruin of

millions of lives, and ever-lasting hostility among people who had lived together for centuries.

1

Al-Islah, J an. 20, 1939. Vol. 6, Issue 3, pp. 7-8.

2

India Office Library, The British Library, London. File: IOL MSS EUR F125/102, pp. 380-1.

3

IOL MSS EUR F125/102, pp. 99-100.

4

IOL MSS EUR F125/102, pp. 294-5.

5

IOL MSS EUR F125/89, pp. 13-4, 34.

6

IOL MSS EUR F125/89, p. 57.

7

Governor of NWFPs Report No.7, April 09, 1940, p. 29.

8

Zaman, Sher. 1987. Khaksar Tehrik Ki Jiddo Juhad (Volume 2). Madni Clinic, Chah Sultan, Rawalpindi, Pakistan,

Khaksar Sher Zaman, p.54.

9

The Tribune, December 05, 1939.

10

Hussain, Syed Shabbir. 1991. Al-Mashriqi: The Disowned Genius. Lahore, Pakistan: J ang Publishers. p. 127.

11

The Tribune, March 25, 1940.

12

IOL MSS EUR F125/89, pp. 22-3.

13

Hussain, p. 193.

IOL: India Office Library, The British Library, London.

2008 Nasim Yousaf. All rights reserved. The above article is protected by US copyright law.

***

The above article appeared in the following newspapers:

News from Bangladesh dated March 18, 2008.

6

http://www.bangladesh-web.com/view.php?hidRecord=191564

Pakistan Christian Post (Philadelphia, USA) dated March 20, 2008.

http://www.pakistanchristianpost.com/articledetails.php?artid=528

Global Politician Magazine (New York, USA) dated April 06, 2008

http://globalpolitician.com/24438-india

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Freedom of British India Through The Lens of The Khaskar MovementDocumento28 pagineFreedom of British India Through The Lens of The Khaskar MovementFernando ProtoNessuna valutazione finora

- Full History. Wikipedia - WPS OfficeDocumento27 pagineFull History. Wikipedia - WPS Officeifatima9852Nessuna valutazione finora

- Kashmir: With A Touch Of Beauty, Global Politics and TerrorDa EverandKashmir: With A Touch Of Beauty, Global Politics and TerrorValutazione: 1 su 5 stelle1/5 (1)

- Kashmir Time LineDocumento5 pagineKashmir Time LinesaaibmirzaNessuna valutazione finora

- Kashmir and IndiaDocumento22 pagineKashmir and IndiaHamza QureshiNessuna valutazione finora

- No Man Can Serve Two MastersDocumento10 pagineNo Man Can Serve Two MastersBidisha SenGuptaNessuna valutazione finora

- Independent Kashmir: An incomplete aspirationDa EverandIndependent Kashmir: An incomplete aspirationNessuna valutazione finora

- The 1947 48 Kashmir War RevisedDocumento76 pagineThe 1947 48 Kashmir War RevisedMohammad UsmanNessuna valutazione finora

- The 1947 48 Kashmir War Revised PDFDocumento76 pagineThe 1947 48 Kashmir War Revised PDFMohammad UsmanNessuna valutazione finora

- Kashmir Conflict - A Study of What Led To The Insurgency in Kashmir ValleyDocumento83 pagineKashmir Conflict - A Study of What Led To The Insurgency in Kashmir ValleyKannan RamanNessuna valutazione finora

- Pakstudt Mis Term AssignmentDocumento3 paginePakstudt Mis Term AssignmentBurhan Ud DinNessuna valutazione finora

- Indo-Pak RelationsDocumento65 pagineIndo-Pak RelationsRishabh Agarwal100% (2)

- Diverse Meanings of Freedom Struggle in South Asia-862Documento7 pagineDiverse Meanings of Freedom Struggle in South Asia-862Abdur Rehman AliNessuna valutazione finora

- An Opportunity For Film and Documentary Makers To Capture The Life of A Renowned Freedom Fighter by Nasim YousafDocumento3 pagineAn Opportunity For Film and Documentary Makers To Capture The Life of A Renowned Freedom Fighter by Nasim YousafNasim Yousaf (Author & Researcher)Nessuna valutazione finora

- Tipu As He Really Was by Gajanan Bhaskar MehendaleDocumento97 pagineTipu As He Really Was by Gajanan Bhaskar MehendaleAjay_Ramesh_Dh_6124100% (1)

- Tipu As He Really WasDocumento97 pagineTipu As He Really Wasvipin100% (1)

- MCQ and Fill in The BlanksDocumento14 pagineMCQ and Fill in The BlanksShahriar ZafirNessuna valutazione finora

- Khawaja Nizamuddin: PakistanDocumento9 pagineKhawaja Nizamuddin: PakistanumairNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction Pakistan Kaisay Bana All VolumesDocumento64 pagineIntroduction Pakistan Kaisay Bana All VolumesTehqeeq0% (1)

- Summary of Clayborne Carson's The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr.Da EverandSummary of Clayborne Carson's The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Quaid.e.Azam Pleads A Case For Pakistan Before Cabinet MissionDocumento8 pagineQuaid.e.Azam Pleads A Case For Pakistan Before Cabinet MissionAlvena RehmanNessuna valutazione finora

- 007 - Kashmir's Accession To India (69-86)Documento18 pagine007 - Kashmir's Accession To India (69-86)soumyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Foreign Policy of Pakistan (A. Sattar)Documento140 pagineForeign Policy of Pakistan (A. Sattar)Tabassum Naveed100% (2)

- A Subaltern Fascism Kannan SrinivasanDocumento37 pagineA Subaltern Fascism Kannan SrinivasanRejane Carolina HoevelerNessuna valutazione finora

- Kashmir Conflict:: A Study of What Led To The Insurgency in Kashmir Valley & Proposed Future SolutionsDocumento83 pagineKashmir Conflict:: A Study of What Led To The Insurgency in Kashmir Valley & Proposed Future SolutionsRavi RavalNessuna valutazione finora

- 50 Inspiring Speeches: Turning points in history, what did they say and why?Da Everand50 Inspiring Speeches: Turning points in history, what did they say and why?Nessuna valutazione finora

- Kashmir Solidarity Day Quiz ResourceDocumento13 pagineKashmir Solidarity Day Quiz ResourceAbdul Hadi TahirNessuna valutazione finora

- Vedas and International LawDocumento6 pagineVedas and International LawutkarshNessuna valutazione finora

- History PDFDocumento19 pagineHistory PDFAbdul HamedNessuna valutazione finora

- Hist EssayDocumento7 pagineHist EssayAbeerah TariqNessuna valutazione finora

- War Against the Taliban: Why It All Went Wrong in AfghanistanDa EverandWar Against the Taliban: Why It All Went Wrong in AfghanistanValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (3)

- A Tale of Two States (A G Noorani) FrontlineDocumento14 pagineA Tale of Two States (A G Noorani) Frontlinekuki_73Nessuna valutazione finora

- Tribal Invasion and Kashmir: Pakistani Attempts to Capture Kashmir in 1947, Division of Kashmir and TerrorismDa EverandTribal Invasion and Kashmir: Pakistani Attempts to Capture Kashmir in 1947, Division of Kashmir and TerrorismNessuna valutazione finora

- CABINET MISSION and PDFDocumento7 pagineCABINET MISSION and PDFKushagra KhannaNessuna valutazione finora

- Bose Sumantra - Kashmir Roots of Conflict Chapter 1Documento17 pagineBose Sumantra - Kashmir Roots of Conflict Chapter 1Isha ThakurNessuna valutazione finora

- The Rise of Sheikh Abdullah As The British Agent: by Narender SehgalDocumento9 pagineThe Rise of Sheikh Abdullah As The British Agent: by Narender SehgalRitika SinghalNessuna valutazione finora

- A Short Introduction To The Kashmir IssueDocumento4 pagineA Short Introduction To The Kashmir IssueAyesha AshfaqNessuna valutazione finora

- Maharaja Radhakishore Manikya: A Clear Vision Out of Chaos: Uma Begam Prof - Chandrika Basu MajumderDocumento7 pagineMaharaja Radhakishore Manikya: A Clear Vision Out of Chaos: Uma Begam Prof - Chandrika Basu Majumderadvsalahuddinahmed014Nessuna valutazione finora

- Indo Pak History Solved Papers CSSDocumento102 pagineIndo Pak History Solved Papers CSSMuhammad Imran50% (2)

- The Independence of India - Graham SpryDocumento14 pagineThe Independence of India - Graham SpryDidem TunçNessuna valutazione finora

- Khilafat Movement in Malabar PDFDocumento40 pagineKhilafat Movement in Malabar PDFRamachandran Meledath100% (1)

- 2 SS Victoria Schofield No-1 2022Documento23 pagine2 SS Victoria Schofield No-1 2022AbdulAzizMehsudNessuna valutazione finora

- 05 - Chapter 1Documento15 pagine05 - Chapter 1Sachin BhatnagarNessuna valutazione finora

- AssignmentDocumento21 pagineAssignmentHuma Tahir KamdarNessuna valutazione finora

- Politics of Genocide - Punjab 1984 - 1998Documento508 paginePolitics of Genocide - Punjab 1984 - 1998navtejpvs100% (14)

- Lahore ResDocumento5 pagineLahore ResMoin SattiNessuna valutazione finora

- Multiple Choices (Tick The Right Answer)Documento7 pagineMultiple Choices (Tick The Right Answer)Shahriar ZafirNessuna valutazione finora

- Khaksar Tragedy (1940) : OrganizationDocumento4 pagineKhaksar Tragedy (1940) : OrganizationNoshki NewNessuna valutazione finora

- Worshipping False Gods: Ambedkar, And The Facts Which Have Been ErasedDa EverandWorshipping False Gods: Ambedkar, And The Facts Which Have Been ErasedValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (11)

- The 1947-48 Kashmir War RevisedDocumento76 pagineThe 1947-48 Kashmir War RevisedShrikant SharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Political History of PakistanDocumento11 paginePolitical History of PakistanArsalan MahmoodNessuna valutazione finora

- Pit. With Time, It Became An Archetype of The Freeborn Englishman. None UsedDocumento21 paginePit. With Time, It Became An Archetype of The Freeborn Englishman. None UsedChatterjee KushalNessuna valutazione finora

- Kashmir IssueDocumento19 pagineKashmir IssueMahnoor HaiderNessuna valutazione finora

- Great Britain and Kashmir, 1947-49Documento22 pagineGreat Britain and Kashmir, 1947-49nagendrar_2Nessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 1Documento30 pagineChapter 1Tushar MahadikNessuna valutazione finora

- Prepared By:: Toshit Chauhan Shubham Jha Deputy Moderator AdvisorDocumento25 paginePrepared By:: Toshit Chauhan Shubham Jha Deputy Moderator AdvisorAakanshi BansalNessuna valutazione finora

- History of PakistanDocumento5 pagineHistory of Pakistanapi-3715420Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Constitution of Free India 1946 A.C.Documento6 pagineThe Constitution of Free India 1946 A.C.Nasim Yousaf (Author & Researcher)Nessuna valutazione finora

- Open Letter To South Asian Research Institutes, Pen America, Asia Society, and Other Organizations Who Support Freedom of Speech in South AsiaDocumento2 pagineOpen Letter To South Asian Research Institutes, Pen America, Asia Society, and Other Organizations Who Support Freedom of Speech in South AsiaNasim Yousaf (Author & Researcher)Nessuna valutazione finora

- "Allama Mashriqi & Allama Iqbal: The Pride of Asia" by Nasim YousafDocumento5 pagine"Allama Mashriqi & Allama Iqbal: The Pride of Asia" by Nasim YousafNasim Yousaf (Author & Researcher)Nessuna valutazione finora

- European Publisher Springer Includes Articles On Allama Mashriqi & Tazkirah inDocumento2 pagineEuropean Publisher Springer Includes Articles On Allama Mashriqi & Tazkirah inNasim Yousaf (Author & Researcher)Nessuna valutazione finora

- "Air Commodore Zafar Masud: A Pakistani Hero" by Nasim YousafDocumento2 pagine"Air Commodore Zafar Masud: A Pakistani Hero" by Nasim YousafNasim Yousaf (Author & Researcher)Nessuna valutazione finora

- 17th Death Anniversary of World Famous Humanitarian: Dr. Akhter Hameed KhanDocumento3 pagine17th Death Anniversary of World Famous Humanitarian: Dr. Akhter Hameed KhanNasim Yousaf (Author & Researcher)Nessuna valutazione finora

- Remembering The World Record Set by PAF Fighter Pilot Zafar Masud and His TeamDocumento2 pagineRemembering The World Record Set by PAF Fighter Pilot Zafar Masud and His TeamNasim Yousaf (Author & Researcher)Nessuna valutazione finora

- An Opportunity For Film and Documentary Makers To Capture The Life of A Renowned Freedom Fighter by Nasim YousafDocumento3 pagineAn Opportunity For Film and Documentary Makers To Capture The Life of A Renowned Freedom Fighter by Nasim YousafNasim Yousaf (Author & Researcher)Nessuna valutazione finora

- Khaksar Tehreek's Twenty-Four Principles and Fourteen Point DecreeDocumento3 pagineKhaksar Tehreek's Twenty-Four Principles and Fourteen Point DecreeNasim Yousaf (Author & Researcher)Nessuna valutazione finora

- Air Commodore M. Zafar Masud - A Pioneer of The Pakistan Air ForceDocumento2 pagineAir Commodore M. Zafar Masud - A Pioneer of The Pakistan Air ForceNasim Yousaf (Author & Researcher)Nessuna valutazione finora

- Allama Mashriqi and The Khaksar Tehrik's Historical DocumentsDocumento1 paginaAllama Mashriqi and The Khaksar Tehrik's Historical DocumentsNasim Yousaf (Author & Researcher)Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Constitution of Free India 1946 A.C.Documento6 pagineThe Constitution of Free India 1946 A.C.Nasim Yousaf (Author & Researcher)Nessuna valutazione finora

- Frequently Asked Questions About Allama Mashriqi and The Khaksar MovementDocumento19 pagineFrequently Asked Questions About Allama Mashriqi and The Khaksar MovementNasim Yousaf (Author & Researcher)Nessuna valutazione finora

- "Human Problem" (A MESSAGE TO THE KNOWERS OF NATURE) by Allama Inayatullah Khan Al-Mashriqi.Documento29 pagine"Human Problem" (A MESSAGE TO THE KNOWERS OF NATURE) by Allama Inayatullah Khan Al-Mashriqi.Nasim Yousaf (Author & Researcher)Nessuna valutazione finora

- "Kafir Kon Log Hain" by Allama Inayatullah Khan Al-MashriqiDocumento40 pagine"Kafir Kon Log Hain" by Allama Inayatullah Khan Al-MashriqiNasim Yousaf (Author & Researcher)67% (3)

- Allama Mashriqi: Educationist and Founder of Islamia College (Peshawar, Pakistan) by Nasim YousafDocumento3 pagineAllama Mashriqi: Educationist and Founder of Islamia College (Peshawar, Pakistan) by Nasim YousafNasim Yousaf (Author & Researcher)Nessuna valutazione finora

- Brills Exp 2Documento4 pagineBrills Exp 2samNessuna valutazione finora

- Electoral Registration Officer (ERO) 2019Documento16 pagineElectoral Registration Officer (ERO) 2019priyakbiswasNessuna valutazione finora

- Sushma Swaraj: Smt. Nirmala Sitharaman Minister of Defence Government of India New DelhiDocumento20 pagineSushma Swaraj: Smt. Nirmala Sitharaman Minister of Defence Government of India New DelhiRuchit SharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Nationalism in India AssignmentDocumento2 pagineNationalism in India AssignmentParth GroverNessuna valutazione finora

- Delimited Landscape of Union Territory of Jammu & Kashmir: Delimitation CommissionDocumento240 pagineDelimited Landscape of Union Territory of Jammu & Kashmir: Delimitation CommissionSudhanshu ShekharNessuna valutazione finora

- CGL 2011 GenDocumento193 pagineCGL 2011 GenPrashant SharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- D. Parliamentary Parties/Groups in Rajya Sabha: Name of Party/Group Room No./ Floor Telephone NoDocumento2 pagineD. Parliamentary Parties/Groups in Rajya Sabha: Name of Party/Group Room No./ Floor Telephone NoMaharshi MadhuNessuna valutazione finora

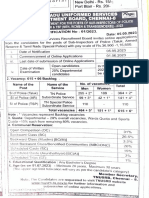

- CBSE Group Mathematical Olympiad ResultDocumento3 pagineCBSE Group Mathematical Olympiad ResultMota ChashmaNessuna valutazione finora

- South RegularisedDocumento18 pagineSouth RegularisedSanjay SsahareNessuna valutazione finora

- 73rd and 74th Constitutional Amendments PDFDocumento21 pagine73rd and 74th Constitutional Amendments PDFSidharth Sreekumar0% (1)

- ASSIGNMENT On Emergency and Its Effect (RIAJUDDIN)Documento22 pagineASSIGNMENT On Emergency and Its Effect (RIAJUDDIN)Abdul MannanNessuna valutazione finora

- Nature of Party System in IndiaDocumento13 pagineNature of Party System in IndiaAnmol BhatnagarNessuna valutazione finora

- International Relation SCORE CardDocumento4 pagineInternational Relation SCORE CardrupeshNessuna valutazione finora

- Statistical Report General Election, 1970 The Legislative Assembly KeralaDocumento162 pagineStatistical Report General Election, 1970 The Legislative Assembly KeralaAKHIL H KRISHNANNessuna valutazione finora

- Port Comb-6Documento8 paginePort Comb-6DIPANKAR MANDALNessuna valutazione finora

- PS - 14 - Rise of Muslim Nationalism in South Asia and Pakistan MovementDocumento31 paginePS - 14 - Rise of Muslim Nationalism in South Asia and Pakistan MovementBali Gondal100% (2)

- 1992 LawSuit (SC) 534Documento72 pagine1992 LawSuit (SC) 534Jagruti NiravNessuna valutazione finora

- Contact Details of State Skill Development MissionsDocumento5 pagineContact Details of State Skill Development MissionsSarojNessuna valutazione finora

- Adobe Scan 05 May 2023Documento1 paginaAdobe Scan 05 May 2023AvisNessuna valutazione finora

- ObcDocumento1 paginaObcPreet ChahalNessuna valutazione finora

- HRD GOI Permission Prosecute Sagle 30112021Documento6 pagineHRD GOI Permission Prosecute Sagle 30112021Acts N FactsNessuna valutazione finora

- 2015 MPP Police Directory Teliphone 51Documento1 pagina2015 MPP Police Directory Teliphone 51AmitDigambariNessuna valutazione finora

- Rapid Practice Test (UPSC Prelims 2020) : Shield IASDocumento6 pagineRapid Practice Test (UPSC Prelims 2020) : Shield IASPravin DeshmukhNessuna valutazione finora

- Electoral Bonds Data - Redemptions and PurchasesDocumento938 pagineElectoral Bonds Data - Redemptions and PurchasesExpress Web100% (1)

- Constituent AssemblyDocumento9 pagineConstituent AssemblyAshley D’cruzNessuna valutazione finora

- LUCKNOW PactDocumento8 pagineLUCKNOW PactRonaldoNessuna valutazione finora

- NEW PH NO HM'sDocumento26 pagineNEW PH NO HM'sHans Ba100% (1)

- State Wise Aadhaar Saturation PDFDocumento3 pagineState Wise Aadhaar Saturation PDFArmaan MujjuNessuna valutazione finora

- Perambalur District: Census of India 2011Documento9 paginePerambalur District: Census of India 2011Mohandas PeriyasamyNessuna valutazione finora