Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Chapter 1.INTROD - LISTENING PDF

Caricato da

Esther Ponmalar CharlesDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Chapter 1.INTROD - LISTENING PDF

Caricato da

Esther Ponmalar CharlesCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Chapter 1: Introduction to Listening

1

Chapter 1: Introduction to Listening

1.1 Preamble

1.2 What is listening?

1.3 Listening and other language skills

1.4 Why is listening difficult?

1.5 Two perspectives of listening

1.6 Bottom-up processing

1.7 Top-down processing

1.8 Bottom-up and top-down processing

Upon completion of this chapter, you should be able to:

Define what is listening

Explain why listening is difficult

Discuss the difference between listening as comprehension and

listening as acquisition

Compare bottom-up and top-down processing in listening

C

Chapter 1: Introduction to Listening

Chapter 2: Teaching Listening

Chapter 3: Listening Activities

Chapter 4: Assessing Listening Skills

5 Chapter 5: Introduction to Speaking

Chapter 6: Teaching Speaking

Chapter 7: Speaking Activities

Chapter 8: Assessing Speaking Skills

Chapter 9: Listening-Speaking Connection

Chapter 1: Introduction to Listening

2

This chapter introduces readers to listening and and how listening is related to other language

skills such as reading, writing and speaking. Focus is on bottom-up and top-down processing

and how in reality both processes play a crucial role in listening. Also discussed are the two

perspectives of listening: acquisition and comprehension; and why listening is difficult.

Listening is used far more than any other language skills (Rivers, 1981) and is often regarded

as a passive activity. The importance of teaching listening comprehension has only been

realised very recently.

Rankin (1996) reported that listening

(46%), speaking (30%), reading

(16%), and writing (9%) involve our

daily communication (see Figure 1.1).

Do you agree? If one was to include

watching television and an hour a

day of conversations; then students

would be spending approximately

50% of their waking hours just

listening.

Look at your own activities. How

much of your time do you spend

listening? How much of your time

during tutorials at AeU is spent listening?

If you ask a group of students to give

a one word description of listening,

some would say hearing; however,

hearing is physical. The following are several definitions of listening.

Listening is following and understanding the sound it is hearing with a purpose and

is built on three basic skills: attitude, attention, and adjustment.

Listening is the absorption of the meanings of words and sentences by the brain which

leads to understanding of facts and ideas. But listening takes attention, or sticking to

the task at hand in spite of distractions.

1.2 What is Listening?

Figure 1.1 Students listening in the classroom

1.1 Preamble

Chapter 1: Introduction to Listening

3

Listening as making sense of oral input by attending to the message (Wolvin &

Coakley, 1996).

Listening as a process entails hearing, attending to, understanding, evaluating, and

responding to spoken messages (Floyed. 2001).

Active listening requires concentration, which is the focusing of your thoughts upon one

particular problem. A person who incorporates listening with concentration is actively

listening. IT is responding to another that encourages communication.

Many teachers or tutors tend to talk too much. Do you think the academic facilitator or tutor

for this course talks too much? If he or she does, it defeats the purpose of tutoring, which is to

allow students to learn by discussion. Rather than turning the session into a mini-lecture,

tutors must actively listen and encourage their students to become active learners.

Do you know that are different types of listening? All of us engage in different types of

listening behaviour depending on purpose of listening. How well we listen, however,

depends on a variety of factors that are influenced by our backgrounds and experiences.

Regardless of the type of listening we are engaged in, there are rules of behaviour we must

learn in order to be an effective listener. By way of illustration, how good would a friend be

at therapeutic listening if he provided no feedback or a doctor if she were to look away when

discussing a diagnosis with a patient? Similarly, a college student may contend that he can

listen simultaneously to a teachers lecture and to a football game. Appropriate

comprehension listening, however, suggests that such distractions severely limit

comprehension. Listening skill varies as the context of communication differs. Wolvin and

Carolyn (1996)] propose five different kinds of listening which help to demonstrate that

listening is an active process rather than a passive one.. See Figure 1.1

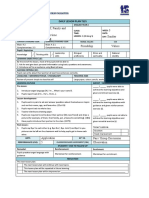

Figure 1.1 Types of Listening

1.2 Types of Listening

TYPES OF

LISTENING

Discriminative

Listening

Comprehension

Listening

Critical

Listening

Therapeutic

Listening

Appreciative

Listening

Chapter 1: Introduction to Listening

4

Discriminative listening is where the objective

is to distinguish sound and visual stimuli. This

objective doesn't take into account the meaning;

instead the focus is largely on sounds. In a basic

level class this can be as simple as

distinguishing the gender of the speaker or the

number of the speakers etc. As mentioned

before the focus is not on comprehending; but

on accustoming the his is where L1 listening

begins - the child responds to sound stimulus

and soon can recognise its parents' voices

amidst all other voices. Depending on the level

of the students, the listening can be discriminating sounds to identifying individual

words.

Where the listener is able to identify and distinguish inferences or emotions through

the speakers change in voice tone, their use of pause, etc. Some people are

extremely sensitive in this way, while others are less able to pick up these subtle

cues. This is one reason why a person from one country finds it difficult to speak

another language perfectly, as they are unable distinguish the subtle sounds that

are required in that language. Likewise, a person who cannot hear the subtleties of

emotional variation in another person's voice will be less likely to be able to discern

the emotions the other person is experiencing. This ability may be affected by

hearing impairment.

Comprehension listening where the focus is on 'understanding the message'. To

comprehend the meaning requires the students be able to differentiate between

different sound and sights is to make sense of them. The listener must understand

many words at their fingertips and also all rules of grammar and syntax by so that

they can understand what others are saying.

Therapeutic listening is one kind of listening where the listener's role is to be a

sympathetic listener without much verbal response. In this kind of listening the

listener allows somebody to talk through a problem. This kind of listening is very

important in building good interpersonal relations.

Critical listening is where listeners have to evaluate the message. Listeners have to

critically respond to the message and give their opinion. Where the listener may be

trying to weigh up whether the speaker is credible, whether the message being given

is logical and whether they are being duped or manipulated by the speaker. This is the

type of listening that we may adopt when faced with an offer or sales pitch that

requires a decision from us. Typically we weigh up the pros and cons of an argument,

determining whether it makes sense logically as well as whether it is helpful to us.

Appreciative listening where the focus is on enjoying what one listens. It is possible

for students listen to to English music, even if they don't understand, they still enjoy

Chapter 1: Introduction to Listening

5

thereby challenging the notion that you need to understand to appreciate. For

example, the listener gains pleasure/satisfaction from listening to a certain type of

music for example. Appreciative sources may also include particular charismatic

speakers or entertainers. These are personal preferences and may have been shaped

through our experiences and expectations.

Besides the above, there are two are two types of listening, based on how deeply you are

listening to the message.

o False Listening occurs when a person is pretending to listen but is not

hearing anything that is being said. He or she may nod, smile or grunt

but not actually take in anything that is said. The person is doing it to

make good impression before he or she moves on or never talk to

that person again (practiced especially among politicians).

o Selective or Biased Listening: Selective listening involves listening for

particular things and ignoring others. We thus hear what we want to

hear and pay little attention to 'extraneous' detail.

o Partial listening: Partial listening is what most of us do most of the

time. We listen to the other person with the best of intent and then

become distracted, either by stray thoughts or by something that the

other person has said.

a) What is listening?

b) Explain the different types of learning. Do you agree with these types

of listening?

c) Think of a time when you felt that a person was not listening to you

when you had something important to say. How did you feel?

Chapter 1: Introduction to Listening

6

Research has found that improvement in listening skill has a positive effect on other language

skills: SPEAKING, READING and WRITING. For example:

Morris and Leavey (2002) in a study on preschoolers found that listening skill

instruction improves preschoolers phonological awareness.

Bergman (2003) revealed that listening and reading stories at the same time contribute

to enhance reading comprehension.

Berninger (2004) showed that the writing skills of students in the primary grades

improved through listening instruction their spelling significantly through listening

instruction, whereas there is a high correlation between.

As the studies reveal, listening comprehension lies at the heart of language learning, but

LISTENING it is the least understood and least researched skill in language learning

especially in second language teaching and learning. Instruction in listening is ignored in

many second language classrooms because teachers are reluctant to teach pronunciation.

However, Hunsaker (1983) found that more than 75% of what children learn in school is

achieved through listening in the classroom. Gilbert (1990) found that K-12 students spend

between 65% and 90% of their school time in learning, which is achieved, in fact, through

listening trajectory.

Receptive Language Expressive Language

Oral Language Listening Speaking

Written Language

Reading

(decoding +

comprehension)

Writing

(handwriting, spelling,

written composition)

Table 1.1 The components of receptive and expressive language

The interrelationship between listening, reading, speaking (oral) and writing is shown in

Table 1.1. Both listening and reading are receptive language, while speaking and

writing are the expressive aspects of language. Receptive language is language that is

heard, processed, and understood by an individual) and Expressive language islanguage

that is generated and produced by an individual.

1.3 Listening and Other Language Skills

Chapter 1: Introduction to Listening

7

a) Listening and Speaking

There has been much debate about the effect

of listening skill on speaking proficiency.

Oral skills (speaking), involves knowing

the sounds of words (phonology), the

structure of sentences (syntactic) and the

meaning of words (semantics). Children

need to to be able to understand words

before they can produce and use them. In

other words, listening precedes speaking and

to a large extent develops speaking.

Rost (1990) proposed the following reasons showing the essential role listening plays to

improve speaking skill.

To understand students must have access to speakers of the language. Only when

they hear what others are talking about do they learn to understand. Failure to

understand the language they hear is an impetus, not an obstacle, to interaction and

learning.

When students hear the language spoken in an authentic situations, they will be more

challenged to attempt to understand the language as other speakers actually use it.

Listening exercises provide teachers with the means for drawing learners attention to

new vocabulary, grammar, and new interaction patterns in the language. This will

build confidence and a willingness to speak in the language,

Listening comprehension precedes speaking, it also develops more speedily than

speaking., I understand everything you say, but I cant repeat it It has been suggested

that that listening must given more attention even before a child learns to speak.

b) Listening and Reading

Listening and reading are components of receptive

language and they share basic cognitive processes.

Listening and reading are linked. Like reading,

listening requires the student to decipher the structure

of sentences and the meaning of words and sentences

Research has shown that reading comprehension is

easier than listening comprehension. Do you agree?

The reason for this is that listeners lack adequate

control over the comprehension of speech, whereas in

reading comprehension, readers can go back and forth

to understand a word or phrase. Why is listening

comprehension neglected in the ESL classroom?

Both listening and reading involve both bottom-up and top-down processing. However,

the words and sentences the listeners hears will have to be stored in memory (so that they do

not forget) and this can be cognitively very demanding. This is unlike, the words and

sentences a person reads, which is not so cognitively demanding because the reader does not

Chapter 1: Introduction to Listening

8

have to store in memory as they are in the book being read. The reader can go back to refer

and extract the meaning when needed. This may explain why listening comprehension is

more difficult than reading comprehension.

To make matters worse, the listener has little control over what is said and because it is

temporary, the listener can retrieve large chunks of the oral information. Also, speaking is

spontaneous, and hesitation, false starts, pauses and corrections are quite common in oral

input and the listener has to deal with this unplanned situation. This situation does not happen

in reading comprehension because the reader always has the book to refer to.

c) Listening and Writing

Writing skill, besides its cognitive process, requires

mechanical attempts to initiate it, so students children need

to be cognitively and physically prepared to embrace this

skill at school age. The development of writing skills rely

heavily on listening skills. Do you agree? Several studies

have shown that the foundations of writing skills is built

upon listening skills. For example, efficient written

language is based on the sounds of a language the listener hears.

Among the four skills, second language learners often complain that listening is the most

difficult to acquire. Both listening and reading are receptive skills, but listening can be more

difficult than reading. WHY?

different speakers produce the same sounds in

different ways, e.g. dialects and accents, stress,

rhythms, intonations & mispronunciations

the listener has little/no control over the speed of

the input of the spoken material

1.3 Why is Listening Difficult?

a) Assess the relationship between listening and the other language skills

such as reading, speaking and writing.

b) Do you agree that listening is a neglected skills in the second language

classroom?

Chapter 1: Introduction to Listening

9

the spoken material is often heard only once (unlike the reading material)

the listener cannot pause to work out the meaning

speech is more likely to be distorted by background noise (e.g. round the classroom)

or the media that transmit sounds

the listener sometimes has to deal simultaneously with another task while listening,

e.g. note-taking

Some researchers attribute poor listening to (a) inadequate attention to the auditory

information, (b) inappropriate listening situations: distractions and noises, (c) difficulty to

distinguish speech sounds, and (d) incompetence in recalling phonemes and manipulating

them explicitly. Instruction of auditory skill contributes to the process of decoding of graphic

images or sounds effectively because it is a sound giving meaning to the letter and graphic

image.

Listening may be examined from two different perspectives:

Listening as:

Listening as Comprehension is the traditional way of

thinking about the nature of listening. This view of listening is

based on the assumption that the main function of listening in

second language learning is to facilitate understanding of

spoken discourse. Let us look at some of the characteristics of

spoken discourse and the special problems they pose for

listeners. Spoken discourse has very different characteristics

from written discourse, and these differences can add a

number of dimensions to our understanding of how we process

speech. For example, spoken discourse is usually

instantaneous. The listener must process it online and there

is often no chance to listen to it again.

Often, spoken discourse strikes the second-language listener as being very fast, although

speech rates vary considerably. Radio monologues may contain 160 words per minute, while

conversation can consist of up to 220 words per minute. The impression of faster or slower

1.4 TWO PERSPECTIVES OF LISTENING

COMPREHENSION

ACQUISITION

Chapter 1: Introduction to Listening

10

speech generally results from the amount of intraclausal pausing that speakers make use of.

Unlike written discourse, spoken discourse is usually unplanned and often reflects the

processes of construction such as hesitations, reduced forms, fillers, and repeats.

Spoken discourse has also been described as having a linear structure, compared to a

hierarchical structure for written discourse. Whereas the unit of organisation of written

discourse is the sentence, spoken language is usually delivered one clause at a time, and

longer utterances in conversation generally consist of several coordinated clauses. Most of

the clauses used are simple conjuncts or adjuncts. Also, spoken texts are often context-

dependent and personal, assuming shared background knowledge. Lastly, spoken texts may

be spoken with many different accents, from standard or non-standard, regional, non-native,

and so on.

Our discussion so far has dealt with one perspective on listening, namely, listening as

comprehension. Everything we have discussed has been based on the assumption that the role

of listening in a language programme is to help develop learners abilities to understand

things they listen to. This approach to teaching of listening is based on the following

assumptions:

Listening serves the goal of extracting meaning from messages.

To do this, learners have to be taught how to use both bottom-up and top-down

processes to understand messages.

The language of utterances the precise words, syntax, and expressions used by

speakers are temporary carriers of meaning.

Once meaning is identified, there is no further need to attend to the form of messages

unless problems in understanding occurred.

Teaching listening strategies can help make learners more effective listeners.

Tasks employed in classroom materials enable listeners to recognize and act on the

general, specific, or implied meaning of utterances.

These tasks include sequencing, true-false comprehension, picture identification,

summarizing, and as well as activities designed to develop effective listening

strategies.

Listening as Acquisition considers listening as inputs that triggers the further development

of second-language proficiency. Schmidt (1990) emphasised the role of consciousness or

noticing in language learning. What is noticing?. We wont learn anything from what we

hear and understand unless we notice something about the input or what we hear. Being

consciousness of the features of the input (or what we hear) can trigger the first stage in the

process language competence. However, for language development to take place, more is

required than simply noticing features of the input (or what we hear). The learner has to try to

incorporate new linguistic items into his or her language repertoire, that is, to use them in oral

production or speaking.

Chapter 1: Introduction to Listening

11

Bottom-up processing refers to using the incoming input as the basis for understanding the

message. Comprehension begins with the received data that is analyzed as successive levels

of organization sounds, words, clauses, sentences, texts until meaning is derived.

Comprehension is viewed as a process of decoding.

We can illustrate this with an example. You listened to the following from a friend:

The guy I met on the bus this morning on the way to work was

telling me he runs an Indian restaurant in Petaling Jaya.

Apparently, its very popular at the moment.

Figure 1.1 Bottom-up processing

The listeners lexical and grammatical competence in a language provides the basis for

bottom-up processing. You take in the raw speech and scan for familiar words and store it in

working memory. Then you use your grammatical knowledge to construct underlying

propositions (or sentences) and work out the relationship between elements of the

propositions or sentences. Then you forget the exact wordings of the propositions or

sentences and retain the meaning (i.e. comprehension) (Clark and Clark, 1977)

To illustrate, you understand your friends utterances using bottom-up processing by mentally

1.5 Listening as Bottom-Up Processing

INFORMATION

Sounds Words

Phrases &

Clauses

Sentences Text Grammar

a) Why is listening difficult for second language learners?

b) Explain the difference between listening as comprehension and

listening as acquisition.

Chapter 1: Introduction to Listening

12

break it down into its components. This is referred to as chunking. Here are the chunks that

guided you to the underlying core meaning of the utterances:

Your friend was on the bus.

There was a guy next to him.

They talked.

The guy said he runs an Indian

restaurant.

Its in Petaling Jaya.

Its very popular now.

The chunks help you to identify the underlying propositions of the utterances expressed by

your friend. It is these units of meaning that you remember, and not the form in which you

initially heard them. You knowledge of grammar helped you to find the appropriate chunks,

and your friend also assisted you in by his intonation and pausing.

Top-down processing, on the other hand, refers to the use of background knowledge in

understanding the meaning of a message. Whereas bottom-up processing goes from language

to meaning, top-down processing goes from meaning to language. The background

knowledge required for top-down processing may be previous knowledge about the topic of

discourse, situational or contextual knowledge, or knowledge in the form of schemata or

scripts plans about the overall structure of events and the relationships between them.

Figure 1.2 Top-down processing

1.6 Listening as Top-Down Processing

INFORMATION

Context

Prior

Knowledge

Prediction

Experience

Chapter 1: Introduction to Listening

13

For example, consider how we might respond to the following utterance:

I heard on the news there was a big earthquake in China last night.

On recognising the word earthquake, we generate a set of questions for which we want

answers:

Where exactly was the earthquake?

How big was it?

Did it cause a lot of damage?

Were many people killed or injured?

What rescue efforts are under way?

These questions guide us through the understanding of any subsequent discourse that we

hear, and they focus our listening on what is said in response to the questions.

Consider this example Imagine I say the following to a colleague at my office one morning:

I am going to the dentist this afternoon.

This utterance activates a schema for going to the dentist. This schema can be thought of as

organized around the following dimensions:

A setting (e.g., the dentists office)

Participants (e.g., the dentist, the patient, the dentists assistant)

Goals (e.g., to have a check up or to replace a filling)

Procedures (e.g., injections, drilling, rinsing)

Outcomes (e.g., fixing the problem, pain, discomfort)

When I return to my office, the following exchange takes place with my colleague:

So how was it?

Fine. I didnt feel a thing.

Because speaker and hearer share understanding of the going to the dentist schema, the

details of the visit need not be spelled out. Minimal information is sufficient to enable the

participants to understand what happened. This is another example of the use of top-down

processing.

Much of our knowledge of the world consists of knowledge about specific situations, the

people one might expect to encounter in such situations, what their goals and purposes are,

and how they typically accomplish them. Likewise, we have knowledge of thousands of

topics and concepts, their associated meanings, and links to other topics and concepts. In

applying this prior knowledge about things, concepts, people, and events to a particular

utterance, comprehension can often proceed from the top down. The actual discourse heard is

used to confirm expectations and to fill out details.

Chapter 1: Introduction to Listening

14

In the real-world listening, both bottom-up and top-down processing generally occur

together. The extent to which one or the other dominates depends on the listeners familiarity

with the topic and content of a text, the density of information in a text, the text type, and the

listeners purpose in listening.

Figure 1.3 Bottom-up and Top-down processing

For example, an experienced cook might listen to a radio chef describing a recipe for cooking

chicken to compare the chefs recipe with her own. She has a precise schema to apply to the

task and listens to register similarities and differences. She makes more use of top-down

processing. However, a novice cook listening to the same program might listen with much

greater attention trying to identify each step in order to write down the recipe. Here, far more

bottom-up processing is needed.

Conclusion

There are two distinct processes involved in listening comprehension. Listeners use 'top-

down' processes when they use prior knowledge to understand the meaning of a message.

Prior knowledge can be knowledge of the topic, the listening context, the text-type, the

culture or other information stored in long-term memory as schemata (typical sequences or

common situations around which world knowledge is organized). Listeners use content words

and contextual clues to form hypotheses in an exploratory fashion.

On the other hand, listeners also use 'bottom-up' processes when they use linguistic

knowledge to understand the meaning of a message. They build meaning from lower level

1.7 Listening as a Combination of the Two Processes

INFORMATION

Context

Prior

Knowledge

Prediction

Experience

Sounds Words

Phrases &

Clauses

Sentences Text Grammar

Chapter 1: Introduction to Listening

15

sounds to words to grammatical relationships to lexical meanings in order to arrive at the

final message. Listening comprehension is not either top-down or bottom-up processing, but

an interactive, interpretive process where listeners use both prior knowledge and linguistic

knowledge in understanding messages. The degree to which listeners use the one process or

the other will depend on their knowledge of the language, familiarity with the topic or the

purpose for listening. For example, listening for gist involves primarily top-down processing,

whereas listening for specific information, as in a weather broadcast, involves primarily

bottom-up processing to comprehend all the desired details.

Listening in another language is a hard job, but we can make it easier by applying

what we know about activating prior knowledge, helping students organise their learning by

thinking about their purposes for listening, and if speaking is also a goal of the classroom,

using well-structured speaking tasks informed by research (Brown, 2006). Besides that,

motivation is equally important. Because listening is so challenging, teachers need to think

carefully about making learning activities successful and interesting.

a) Activating Prior Knowledge to Improve Listening Comprehension

One very important idea for teaching listening is that listening courses must make use of

students prior knowledge in order to improve listening comprehension. We have known at

least since the 1930s that

peoples prior knowl edge has an

effect on their cognition. Prior

knowledge is organised in

schemata (the plural form of

schema): abstract, generalized

mental representations of our experience that are available to help us understand new

experiences. Another way to look at this phenomenon is the idea of scripts. For example, you

will have different script on the sequence of ordering a meal in an American fast food

restaurant compared to the script at a Nasi Kandar restaurant.

You are in Spain (you do not speak Spanish) and want to buy a train ticket. Suddenly, the

station master approaches you and says huelga and you remember that it means strike. You

a) What is bottom-up processing in listening?

b) What is top-down processing in listening?

c) Explain the combination of the two processes in listening.

1.7 Helping Listeners in Understand What They Hear

Chapter 1: Introduction to Listening

16

conclude that he is trying to tell you that there will no train services because workers are on

strike. Here you are using your prior knowledge to understand what the station master was

trying to tell you.

Unlike reading, listening must be done in real time; there is no second chance, unless, of

course, the listener specifically asks for repetition. Listening involves understanding all sorts

of sounds and blending of words. There are false starts, pauses and hesitations to be dealt

with. Generally, studies have shown that readers recalled more details than listeners, and that

listeners, while understanding a lot of the main ideas, had to fill in the blanks in their

understanding by guessing at context. This explains why listeners have to use their prior

knowledge in understanding what is being said by the speaker.

Some people are inherently better listeners than others. But even the best listeners, as anyone

who has taught a language knows, can have a difficult time. Listening in a second language is

subject to individual differences depending on their ability to process and store information.

The task of the teacher is to first understand that all humans are limited in their ability to

process information. Hence, they must find a way to help students to activate their prior

knowledge to take away some of the difficulties they face. It is important to give students the

opportunity to use what they already know their prior knowledge to help them do the task.

Activating prior knowledge, in addition to helping comprehension, motivates students by

bringing their lives into the lesson.

b) Establishing the Purpose for Listening

We always have a purpose for listening. We may listen to the radio in the morning to decide

whether to wear a coat or take an umbrella. We may listen to a song for pleasure. We listen in

different ways based on our purpose. Having a purpose helps us listen more effectively. For

example, when listening to the weather report,

fishermen listen and decide whether to go out to

sea.

We can help students listen more effectively if

we spend some time teaching them about

purposes for listening. If students know why they

are listening, they are more focused.

Listening for main ideas means that the listener wants to get a general idea of what is

being said. The details are less important.

Listening for details is something we do every day. For example, we need the details

when we are getting directions to someplace like a friends home. Just understanding

the topic in this case does us no good.

Listeners have to listen between the lines to figure out what really is meant.

Speakers do not always say exactly what they mean. That is, important aspects of

meaning are sometimes implied rather than stated.

In conclusion, systematically presenting (1) listening for main ideas, (2) listening for details,

and (3) listening and making inferences helps students develop a sense of why they listen and

which skill to use to listen better. Teachers can build skills by asking students to focus on

Chapter 1: Introduction to Listening

17

their reason for listening each time they listen. This is a form of strategy training. Strategies

are clearly a way to ease the burden of listening and should be taught.

KEY WORDS

SUMMARY

Listening is used far more than any other language skills and is often regarded as a

passive activity.

Listening in another language is a hard job, but we can make it easier by applying

what we know about activating prior knowledge and helping students organise their

learning by thinking about their purposes for listening.

Listening may be examined from two different perspectives: acquisition and

comprehension.

Children need to to be able to understand words before they can produce and use

them. In other words, listening precedes speaking and to a large extent develops

speaking.

Research has shown that reading comprehension is easier than listening

comprehension.

Discuss the ways in which a teacher can support listeners so that they can become

more effective listeners in the second language classroom.

Listening skills

Listening comprehension

Bottom-up processing

Top-down processing

Discriminative listening

Therapeutic listening

Appreciative listening

False listening

Activating prior knowledge

Listening as acquisition

Chapter 1: Introduction to Listening

18

The development of writing skills rely heavily on listening skills.

Among the four skills, second language learners often complain that listening is the

most difficult to acquire.

Bottom-up processing refers to using the incoming input as the basis for

understanding the message.

Top-down processing, on the other hand, refers to the use of background knowledge

in understanding the meaning of a message.

In the real-world listening, both bottom-up and top-down processing generally occur

together.

REFERENCES

Brown, S. (2006). Teaching Listening. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Wolvin, A. and Coakley, C. (1996). Listening. Madison, WI: Brown/Benchmark, 1996

Hossein Bozorgian (2012) Listening Skill Requires a Further Look into Second/Foreign

Language Learning, ISRN Education. Article ID 810129, 10 pages

Hunsaker, R. (1983). Speaking and Listening. Boston: Morton Publishing.

Rickards, J. (2008). Teaching Listening and Speaking. Cambridge University Press.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- Thesis Chapter 1Documento21 pagineThesis Chapter 1Bea DeLuis de TomasNessuna valutazione finora

- ESP - English For Specific PurposesDocumento200 pagineESP - English For Specific PurposesBuddyNessuna valutazione finora

- Materials Development For Language Learning and TeachingDocumento37 pagineMaterials Development For Language Learning and Teachingالخُط وصل يا رجاله86% (7)

- Analysing A Sample LSA (Skills) BEDocumento23 pagineAnalysing A Sample LSA (Skills) BECPPE ARTENessuna valutazione finora

- Desra Miranda, 170203075, FTK-PBI, 085214089391Documento65 pagineDesra Miranda, 170203075, FTK-PBI, 085214089391Camille RoaquinNessuna valutazione finora

- MENTALISM Slides Power PointDocumento9 pagineMENTALISM Slides Power PointPatty Del Pozo Franco50% (4)

- Rules of Teaching GrammarDocumento29 pagineRules of Teaching GrammarEhman68% (19)

- Unit 2 - Paper 2 - Section CDocumento3 pagineUnit 2 - Paper 2 - Section CEsther Ponmalar CharlesNessuna valutazione finora

- Triumph Redong Vol 1Documento112 pagineTriumph Redong Vol 1Mohamad Aizat67% (3)

- Unit 2 - Paper 1 - QNS 21Documento1 paginaUnit 2 - Paper 1 - QNS 21Esther Ponmalar CharlesNessuna valutazione finora

- Tick ( ) The Correct Answer: UPSR SK Paper 1-Question 22Documento3 pagineTick ( ) The Correct Answer: UPSR SK Paper 1-Question 22Esther Ponmalar CharlesNessuna valutazione finora

- Triumph Redong Vol 3 PDFDocumento97 pagineTriumph Redong Vol 3 PDFfathihadifNessuna valutazione finora

- Question Pen Sec. B Set 3Documento3 pagineQuestion Pen Sec. B Set 3Esther Ponmalar CharlesNessuna valutazione finora

- UPSR SK Paper 1-Question 22: Yr 6 SK Textbook Unit 1 - Page 5Documento1 paginaUPSR SK Paper 1-Question 22: Yr 6 SK Textbook Unit 1 - Page 5haznan2088Nessuna valutazione finora

- Triumph Redong Vol 2 PDFDocumento100 pagineTriumph Redong Vol 2 PDFParthiban Muthiah100% (2)

- Question Pen Sec. B Set 1Documento2 pagineQuestion Pen Sec. B Set 1Esther Ponmalar CharlesNessuna valutazione finora

- Question Pen Sec. B Set 1Documento2 pagineQuestion Pen Sec. B Set 1Esther Ponmalar CharlesNessuna valutazione finora

- Question Pen Sec. B Set 1Documento2 pagineQuestion Pen Sec. B Set 1Esther Ponmalar CharlesNessuna valutazione finora

- Question Pen Sec. B Set 3Documento3 pagineQuestion Pen Sec. B Set 3Esther Ponmalar CharlesNessuna valutazione finora

- Question Pen Sec. A Set 1Documento1 paginaQuestion Pen Sec. A Set 1Esther Ponmalar CharlesNessuna valutazione finora

- Question Pen Sec. C Set 3Documento3 pagineQuestion Pen Sec. C Set 3Esther Ponmalar CharlesNessuna valutazione finora

- Question Pen Sec. A Set 2Documento1 paginaQuestion Pen Sec. A Set 2Esther Ponmalar CharlesNessuna valutazione finora

- Section C (25 Marks) This Section Consists of Two Questions. Answer One Question OnlyDocumento3 pagineSection C (25 Marks) This Section Consists of Two Questions. Answer One Question OnlyEsther Ponmalar CharlesNessuna valutazione finora

- Question Pen Sec. B Set 2Documento3 pagineQuestion Pen Sec. B Set 2Esther Ponmalar CharlesNessuna valutazione finora

- Question Pen Sec. C Set 1Documento5 pagineQuestion Pen Sec. C Set 1Esther Ponmalar CharlesNessuna valutazione finora

- Question Pen Sec. B Set 1Documento2 pagineQuestion Pen Sec. B Set 1Esther Ponmalar CharlesNessuna valutazione finora

- Question Pen Sec. A Set 3Documento2 pagineQuestion Pen Sec. A Set 3Esther Ponmalar CharlesNessuna valutazione finora

- Baca Petikan Di Bawah Dan Jawab Soalan-Soalan Yang BerikutDocumento2 pagineBaca Petikan Di Bawah Dan Jawab Soalan-Soalan Yang BerikutEsther Ponmalar CharlesNessuna valutazione finora

- Question 12-15 Set 3Documento1 paginaQuestion 12-15 Set 3Esther Ponmalar CharlesNessuna valutazione finora

- Questions 24 and 25: Soalan Yang BerikutnyaDocumento3 pagineQuestions 24 and 25: Soalan Yang BerikutnyaEsther Ponmalar CharlesNessuna valutazione finora

- Clothes and Food Fest: Teliti Notis Dan Baca Dialog Yang Diberi. Kemudian, Jawab Soalan-Soalan Yang BerikutnyaDocumento2 pagineClothes and Food Fest: Teliti Notis Dan Baca Dialog Yang Diberi. Kemudian, Jawab Soalan-Soalan Yang BerikutnyaEsther Ponmalar CharlesNessuna valutazione finora

- Question 12-15 Set 1Documento1 paginaQuestion 12-15 Set 1Esther Ponmalar CharlesNessuna valutazione finora

- Section C (25 Marks) This Section Consists of Two Questions. Answer One Question OnlyDocumento3 pagineSection C (25 Marks) This Section Consists of Two Questions. Answer One Question OnlyEsther Ponmalar CharlesNessuna valutazione finora

- Baca Surat Berikut Dan Jawab Soalan-Soalan BerikutDocumento2 pagineBaca Surat Berikut Dan Jawab Soalan-Soalan BerikutEsther Ponmalar CharlesNessuna valutazione finora

- Look at The Picture and Choose The Best Answer. Lihat Gambar Dan Pilih Jawapan Yang TerbaikDocumento2 pagineLook at The Picture and Choose The Best Answer. Lihat Gambar Dan Pilih Jawapan Yang TerbaikEsther Ponmalar CharlesNessuna valutazione finora

- Question 7-11 Set 2Documento2 pagineQuestion 7-11 Set 2Esther Ponmalar CharlesNessuna valutazione finora

- Question 1-6 Set 3Documento2 pagineQuestion 1-6 Set 3Esther Ponmalar CharlesNessuna valutazione finora

- Common Writing Problems and Writing Atti 18cf6e27Documento18 pagineCommon Writing Problems and Writing Atti 18cf6e27Kenneth FlorescaNessuna valutazione finora

- Adult Coursebooks: Brian Tomlinson and Hitomi MasuharaDocumento17 pagineAdult Coursebooks: Brian Tomlinson and Hitomi MasuharacalookaNessuna valutazione finora

- A Multiple Intelligences Approach: Intuitive English Learning - A Case Study For k-1 StudentsDocumento5 pagineA Multiple Intelligences Approach: Intuitive English Learning - A Case Study For k-1 StudentsDevika MakhijaNessuna valutazione finora

- Willingness To Communicate in The Second LanguageDocumento4 pagineWillingness To Communicate in The Second LanguageAfifahAbdullahNessuna valutazione finora

- BI Y2 LP TS25 (Unit 5 LP 1-25)Documento27 pagineBI Y2 LP TS25 (Unit 5 LP 1-25)Mai Abd HamidNessuna valutazione finora

- The Role of The First LanguageDocumento1 paginaThe Role of The First Languagequynhthy189Nessuna valutazione finora

- Applying Indirect Strategies To The 4 LG SkillsDocumento13 pagineApplying Indirect Strategies To The 4 LG Skillsmăruţa100% (2)

- Intensive and Extensive Reading in Improving TeachDocumento13 pagineIntensive and Extensive Reading in Improving Teachapi-533355836Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Role of Parents Towards Second Language Acquisition in A Three Year Old ChildDocumento10 pagineThe Role of Parents Towards Second Language Acquisition in A Three Year Old Childcitra wulanNessuna valutazione finora

- Escobar, Evnistskaya, Actimel CLIL Experience, Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona, UABDocumento31 pagineEscobar, Evnistskaya, Actimel CLIL Experience, Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona, UABIreneNessuna valutazione finora

- A Thesis On LinguisticsDocumento107 pagineA Thesis On LinguisticsMegha VaishnavNessuna valutazione finora

- Assignment 2 - Second Language Acquisition - Deadline 23rd SeptemberDocumento6 pagineAssignment 2 - Second Language Acquisition - Deadline 23rd SeptemberMc ReshNessuna valutazione finora

- The Scopes of Applied Linguistics: Language and TeachingDocumento5 pagineThe Scopes of Applied Linguistics: Language and TeachingsalmannNessuna valutazione finora

- Developing Cultural Awareness in Foreign Language Teaching PDFDocumento5 pagineDeveloping Cultural Awareness in Foreign Language Teaching PDFDulce Itzel VelazquezNessuna valutazione finora

- Miller - Language Use, Identity, and Social Interaction - Migrant Students in AustraliaDocumento33 pagineMiller - Language Use, Identity, and Social Interaction - Migrant Students in Australiatwa900Nessuna valutazione finora

- Input and Output in The SLA ProcessDocumento14 pagineInput and Output in The SLA ProcessSra. Y. DávilaNessuna valutazione finora

- Review of Related LiteratureDocumento26 pagineReview of Related LiteratureGretchie Mae Combes VargasNessuna valutazione finora

- CM5 The Challenges of Teaching English As A Second LanguageDocumento37 pagineCM5 The Challenges of Teaching English As A Second LanguageElgie Acantilado MipranumNessuna valutazione finora

- Second Language Learning - HatchDocumento18 pagineSecond Language Learning - HatchDhara ZatapathiqueNessuna valutazione finora

- методикаDocumento95 pagineметодикаАйкумыс ДарбаеваNessuna valutazione finora

- Listening & Speaking PDFDocumento23 pagineListening & Speaking PDFAdil A BouabdalliNessuna valutazione finora

- Tefl G7Documento45 pagineTefl G7Umi KalsumNessuna valutazione finora

- 21 Reasons Why Filipino Children Learn Better While Using Their Mother TongueDocumento34 pagine21 Reasons Why Filipino Children Learn Better While Using Their Mother TongueRose DumayacNessuna valutazione finora